Background: Wnt signaling plays an important role in somatic cell reprogramming.

Results: Through interaction with Klf4, Oct4 and Sox2, β-catenin enhances expression of pluripotency circuitry genes to promote somatic cell reprogramming. However, β-catenin is not required for pluripotent stem cell self-renewal.

Conclusion: Wnt/β-catenin signaling has different roles in pluripotent stem cell self-renewal and somatic cell reprogramming.

Significance: These studies reveal novel mechanisms underlying the reprogramming process by Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Keywords: Beta-catenin, Gene Expression, Induced Pluripotent Stem (iPS) Cell, Reprogramming, Wnt Signaling, c-myc

Abstract

Wnt signaling has been implicated in promoting somatic cell reprogramming. However, its molecular mechanisms remain unknown. Here we report that Wnt/β-catenin enhances iPSCs induction at the early stage of reprogramming. The augmented reprogramming induced by β-catenin is not due to increased total cell population or activation of c-Myc. In addition, β-catenin interacts with reprogramming factors Klf4, Oct4, and Sox2, further enhancing expression of pluripotency circuitry genes. These studies reveal novel mechanisms underlying the regulation of reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency by Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Introduction

β-Catenin is an integral component of the Wnt signaling pathway that regulates multiple cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, cell destination, and organogenesis (1) When β-catenin is not assembled in a complex with adhesion molecule cadherin, it usually forms a complex with Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway. While bound to Axin, β-catenin is constitutively phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3)3 (2–4) and other protein kinase complexes. In its phosphorylated form, β-catenin is targeted for ubiquitination and subsequently degraded. However, in the presence of Wnt3a, GSK-3 is inhibited, and β-catenin is de-phosphorylated and thus stabilized, whereupon it accumulates in the cytoplasm and is translocated to the nucleus to activate T-cell factor (TCF), driving downstream expression of many important genes required for cell maintenance (5–7).

The role of Wnt/β-catenin in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) self-renewal and maintenance is a subject of ongoing debate. For instance, it has been shown that activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is sufficient to maintain ESC self-renewal when the core self-renewal Oct4/Sox2/Nanog circuit is intact, and that use of a GSK-3 inhibitor sustains the pluripotent state of ESCs (8) Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), typically added to murine ESCs (mESCs) culture to maintain pluripotency, activates the STAT3 signaling pathway, which ultimately activates c-Myc (9) one of the transgenes involved in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) induction (10). β-Catenin activates c-Myc as well (11). A recent study demonstrated that β-catenin was able to form a complex with Oct4 in a TCF-independent manner to enhance mESC pluripotency (12). These results indicate that β-catenin seems to be important for self-renewal. However, others have reported that β-catenin overexpression or treatment with Wnt3a promotes proliferation while also inducing differentiation of ESC (13). Very recently, a series of reports indicates that β-catenin may not be required for pluripotent stem cell self-renewal and expansion (14) (15) (16). These contradictory findings suggest that the effect of β-catenin may be context-dependent.

The technology to induce somatic cells to revert to iPSCs by way of transduction of several transcription factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, Klf4, Nanog, and Lin28) has created the possibility of generating individualized iPSCs for patient-specific therapy or drug screening (10) (17) (18). However, current reprogramming methods remain very inefficient. Wnt3a and GSK-3β inhibitors have been shown to successfully stimulate both fusion-induced and reprogramming factor-induced reprogramming (19) (20). However, the identity of the downstream reprogrammer that is activated by β-catenin signaling is still not known. Understanding the role of β-catenin in ESCs and iPSCs self-renewal and reprogramming could lead to more efficient reprogramming strategies, enabling large-scale production of iPSCs and generation of patient-specific iPSCs for clinical application. Comprehension of these underlying mechanisms may also lead to the development of chemical induction of iPSCs, i.e. employing small molecules and circumventing the need for transgene and oncogene usage.

In this study, we found that Wnt/β-catenin signaling does enhance reprogramming efficiency. The augmented reprogramming induced by β-catenin is not due to increased total cell population or activation of c-Myc. The enhancing effect is primarily at the initial stage of the reprogramming process, and the interaction with TCF is important. β-Catenin also interacts with the reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4, and further enhances expression of endogenous core pluripotency genes (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Sall4) and activated the pluripotent network. Although Wnt/β-catenin is critical for reprogramming, it seems not to be required for maintenance of pluripotent stem cell identity. Thus, β-catenin has different roles in pluripotent stem cell self-renewal and reprogramming regulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

293T Cell and Lentivirus Preparation

293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone), 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 mg/ml streptomycin. To prepare the viruses, 293T cells were grown to 90% confluence in 10-cm tissue-culture dishes. The medium was removed and replaced with 7 ml of fresh 293T medium. 3 μg of the transgene plasmid, 2 μg of the viral envelope plasmid pMD2.G, and 5 μg of the viral packaging plasmid psPAX2 were added to 500 μl of DMEM. Simultaneously, the 5–20 μl of polyethylenimine (PEI) was added to another 500 μl of DMEM. These two mixtures were combined and vortexed for 5 s and then distributed dropwise to the 293T cells. The next day, 5 ml of fresh 293T medium was added to each dish. After incubation for 48 h, the virus-containing medium was collected, filtered with a 0.45-μm filter and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 28,000 rpm for 2 h. Concentrated viruses were reconstituted in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the titers were determined later with 293T cells.

Reprogramming of Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs)

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were obtained as described (21). Briefly, primary MEFs were generated from embryonic day (E)-13.5 Ctnnb1loxP/loxP; R26R mouse embryos in which the β-catenin gene (Ctnnb1) is flanked by loxP sites. β-Catenin MEFs were plated on a 10-cm tissue-culture dish and transduced twice with five lentiviruses, including those expressing the four reprogramming factors plus rtTA. After 2 days of infection, the MEF medium was replaced with mouse ESC medium (Glasgow minimum essential medium with 15% FBS, 2 mm glutamine, 0.1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, leukemia-inhibitory factor (LIF) at 10 ng/ml) with 0.25 μg/ml of doxycycline. Medium was changed every day. After about 3 weeks of incubation, mature iPSC colonies were isolated manually and transferred individually to 4-well plates for further propagation.

Mouse Pluripotent Stem Cells and iPSCs-derived Neural Stem Cell (NSCs) Culture

Mouse pluripotent stem cells, including ESCs and iPSCs, were maintained in mouse ESCs medium on 0.1% gelatin-coated plates. To obtain iPSC-derived NSCs, iPSCs were dissociated into single cells with 0.05% trypsin, and maintained in mESCs medium without LIF on non-adherent plates for 4 days to form embryoid bodies. After another week of culture in 2% B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) defined medium, neurospheres (NSs) were formed within 3–5 days with addition of 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) supplement. NSs were dissociated into single cells with 0.05% trypsin at 37 C° for 10 min. NSCs were then cultured as a monolayer on poly-l-lysine- and fibronectin-coated dishes in 2% B27 defined medium with 20 ng/ml bFGF addition. Medium was changed every 2 days.

Reprogramming iPSCs-derived NSCs to iPSCs by Addition of Doxycycline

Identical NSCs were seeded on irradiated MEFs or 0.1% gelatin-coated plates in B27 defined medium without bFGF supplementation. After 1 day, medium was switched to mESC medium with LIF and 0.25 μg/ml doxycycline supplementation. Medium was changed every 2 days and secondary iPS colonies emerged within 1 week, and cultures were fixed after 12–14 days for AP staining. Based on expression pattern of SSEA1 and Oct4 (22), we divided some reprogramming process into 3 stages. Early stage was defined from doxycycline addition the day 1–4, middle stage was from day 5–8 when SSEA1 expression emerges, and the last stage was from day 9–12 days when Oct4 gene starts to be expressed.

Plasmid DNA Preparation and Construction

Plasmid DNA was amplified by using Escherichia coli DH5α chemico-competent cells and the protocol obtained from Invitrogen. The doxycycline-inducible viral expression vector was obtained according to previous protocol (21). Plasmid β-catenin SA (pCAG-IP-myc-β-catenin) and its truncated C-terminal form of β-catenin (β-catenin N12) were gifts of Dr. Jun-ichi Miyazaki (23) and Dr. Hiroshi Koide (24).

Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) Staining, LacZ Staining, and Immunostaining

Cultured samples were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. AP staining was done according to the previous protocol (25) using the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). LacZ staining was done using a mixture of LacZ staining solution and X-gal substrate (added immediately before staining) and incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 1 h or kept overnight in the dark at room temperature. AP and Laz-positive colonies were imaged and the numbers of AP and Laz positive colonies were counted using ImageJ software. All the experiments were done in at least triplicates, and the results were analyzed by student t test. For immunostaining, cells were incubated with stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 (SSEA1) primary antibody (1:400; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) or anti-β-catenin primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) with 0.05% Triton X-100 for 1 h, washed with PBS, and incubated with secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgM, 1:1000; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA,) for 30 min. After washing, DAPI was added for 5 min, and then the cells were washed with PBS 3 times for 5 min each. Cells were then analyzed under a fluorescence microscope.

FACS Analysis

FACS was performed by resuspending cells to be sorted in FACS buffer (5% FBS in PBS), and sorted in a FACS BD ISA 2 special order system instrument. For FACS analysis, cells were dissociated with 0.05% trypsin to single cells and fixed by 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min at room temperature. After washing, cells were incubated with SSEA1 primary antibody for 20 min followed by secondary antibody incubation for 15 min. After washing and centrifugation, cells were resuspended in PBS. The sample absent the primary antibody was used as a negative control. FACS was completed by using an FITC filter and BD FACSDIVA software.

Reverse-transcription (RT), Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), and Real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR were done as previous described (25). Briefly, total RNA was isolated from iPS cells using an RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RT was performed using a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) by using 1.5 μg of RNA. PCR was performed using a TaqDNA Polymerase kit (Invitrogen) to evaluate total gene expression. qRT-PCR was performed by using 2x iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and the cDNA pool was subjected to qRT-PCR on an AB 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The following conditions were used for qRT-PCR: 5 min at 95 °C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 55 °C. Reactions were carried out in triplicate with the delta Ct method. The sequences of RT-PCR and qRT-PCR primers are given in the supplementary data.

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were performed as previously described (21). Briefly, 293T cells were lysed with KLB buffer. Cell lysate was then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected for the immunoprecipitation assay. Protein A/G-agarose beads (Pierce 20421) were used for pre-clearing and precipitation. The antibodies used for immunoprecipitation were anti-Flag (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-HA, anti-Myc, and anti-β-catenin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Anti-β-catenin, anti-actin-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-Sall4 (Abcam) were used for immunoblotting.

Luciferase Assays

Luciferase reporter (25) assays were performed as previously described. 293T cells were transfected by using the PEI transfection method (see 293T cell and lentivirus preparation above) along with the reporter plasmid and various expression vectors. Plasmid pcDNA3 was added to the transfections to make the total concentration of DNA the same for each reaction. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell extracts were then prepared and luciferase assays were done by using a Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A SpectraMax M5 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices) was used for sequential assay of firefly and Renilla luciferases. All the experiments were done in at least triplicates and the results were analyzed by Student's t test. To perform the Luciferase reporter assays on pluripotent stem cells (mESCs or iPSCs) and iPSC-derived NSCs, the plasmid DNAs were delivered into the cells by nucleofection by using Amaxa Nucleofector technology.

RESULTS

Generation of an Inducible Cre-ERTM Ctnnb1loxP/loxP β-Catenin loxP/loxP iPSC Line

To establish first-generation β-cateninloxP/loxP iPSC lines, E13.5 Ctnnb1loxP/loxP mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (21) were infected with lentiviral vectors expressing Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc under doxycycline control (TRE promoter) combined with a constitutively active lentivirus expressing rtTA with a puromycin selection cassette. After 3 weeks of induction, ESC-like colonies were isolated and transferred to another plate for propagation to obtain stable and mature Ctnnb1loxP/loxP iPSC lines. After isolation of a stable cell line, lentiviruses containing the FUW-Cre-ERTM gene construct were introduced into Ctnnb1loxP/loxP iPSCs, allowing for conditional deletion of β-catenin by activation of Cre-recombinase with tamoxifen addition (Fig. 1A). For simplicity, we refer to this FUW-Cre-ERTM-containing Ctnnb1loxP/loxP iPSC line as the β-catenin loxP/loxP iPSC line. When Cre-recombinase is activated by tamoxifen, Cre-ERTM will excise the β-catenin gene by site-specific recombination at the loxP sites flanking the gene. The floxed β-catenin iPS cells are referred to as β-catenin−/− iPSCs. In these cells, the lacZ reporter construct, R26R, will also undergo Cre-promoted recombination, resulting in deletion of an expression cassette before the LacZ gene and allowing expression of a β-galactosidase gene. This enables us to confirm β-catenin deletion by using lacZ staining (data not shown). Phenotypically, β-catenin−/− iPSCs are indistinguishable from mESCs and β-catenin iPSCs, based on cell morphology, AP staining, and SSEA1 staining (data not shown).

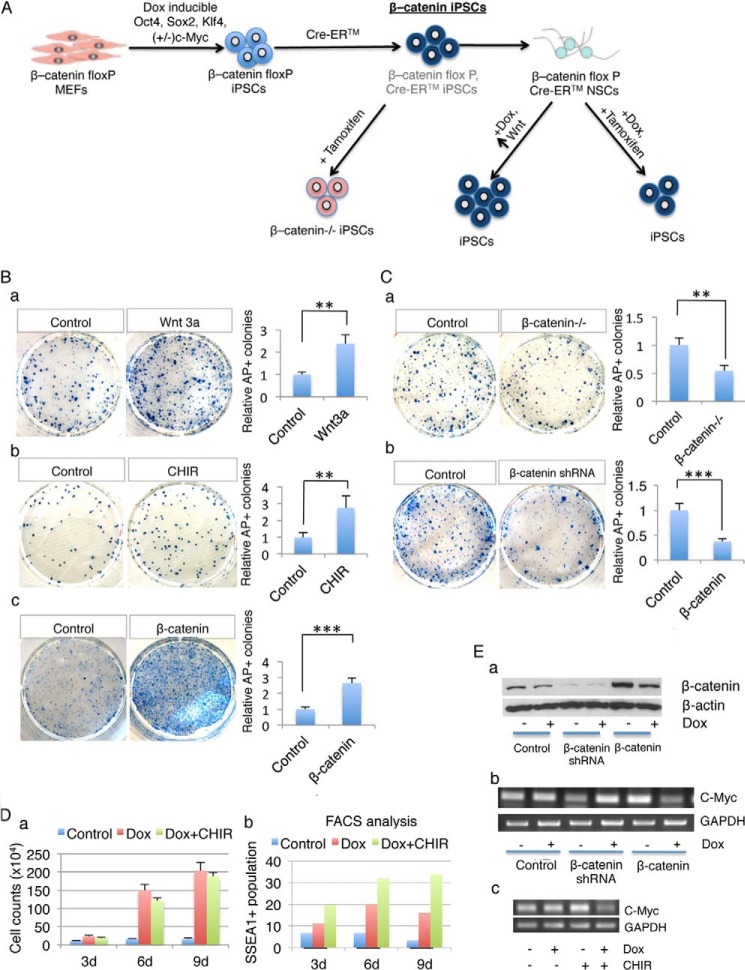

FIGURE 1.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling enhances iPSCs generation, an effect not due to increased cell number or activation of the c-Myc gene. A, scheme of the experimental design showing derivation of first-generation of β-catenin flox iPSCs, and generation of secondary iPSCs from β-catenin flox iPSCs-derived NSCs. The promoting and inhibiting effects of Wnt signaling on reprogramming efficiency are illustrated. B, β-catenin activation by Wnt3a, GSK3β inhibitor CHIR or expression of a constitutively active β-catenin mutant gene (β-catenin 4A) all significantly increased iPSCs induction (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; **, p < .05). NSCs were cultured in mESCs medium with doxycycline for 14 days and treated with Wnt3a or CHIR (a and b) or transfected with β-catenin 4A plasmid (c) (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; ***, p < .01). a–c, left panels, AP staining represents the iPSCs colonies undergoing reprogramming, and right panels, quantification of AP-positive colonies from left panels representing the fold change in the number of AP-positive colonies compared with the control sample. C, deletion of the β-catenin gene or knock down β-catenin expression by shRNA significantly reduces iPSCs induction (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; **, p < .05). The floxed β-catenin gene was deleted by tamoxifen treatment, or β-catenin shRNA was introduced into NSCs by transfection. Cells were then fixed and AP staining was performed (a and b). Quantification of AP-positive colonies from (a) and (b) represents the fold change in the number of AP-positive colonies compared with the control sample (right panels of a and b). D, increased iPSCs generation by Wnt/β-catenin signaling is not due to increased total cell number. NSCs were treated with or without doxycycline or CHIR for 3, 6, or 9 days and NSCs were collected at each time point to perform cell counts (a) or FACS analysis for SSEA1 positive populations (b). Duplicate samples were used for statistical analysis. E, β-catenin activation suppresses endogenous c-Myc gene expression in NSCs that overexpress three (OSK) or four (OSKM) reprogramming factors. a and b, β-catenin shRNA or constitutively active β-catenin 4A gene was introduced through lentivirus infection into NSCs derived from 4 factor (OSKM)-induced iPSCs and treated with or without doxycycline or CHIR for 72 h. The knockdown of β-catenin expression was confirmed by Western blot (a). Expression of endogenous c-Myc was determined by RT-PCR (b). C-Myc gene expression in NSCs derived from 3 factors (OSK) induced iPSCs differentiation and treated with or without doxycycline or CHIR or for 72 h.

β-Catenin Enhances Reprogramming Efficiency

To increase the reprogramming efficiency and reduce the data variation we used the secondary iPS cell induction system to complete all of our studies (21) (26). There are several advantages about the secondary iPS cell induction system. The cell derived from first generation iPS cells all contains the same transgenes of reprogramming factors under doxycycline-inducible promoters. As a result, the iPS cell induction efficiency will be higher and the variation between samples will be lower than the conventional iPS cell induction.

To derive genetically homogeneous NSCs directly from first-generation iPSCs, β-cateninloxP/loxP iPSCs were induced to form embryoid bodies and then neurosphere, from which NSCs were generated. To derive second-generation iPSCs, NSCs were plated at the same density onto 0.1% gelatin or irradiated MEF plates. After overnight incubation, the medium was replaced with mESCs medium containing 0.25 μg/ml doxycycline. Colonies emerged within 1 week, and mature iPSCs colonies appeared in 12–14 days. These cells were fixed and AP staining was performed. We calculated reprogramming efficiency by counting the number of AP-positive colonies.

Previous reports have demonstrated that Wnt3a promotes reprogramming efficiency (20). A similar result was obtained using our reprogramming system. β-cateninloxP/loxP iPSCs-derived NSCs were treated with Wnt3a 10 μg/ml under mESCs culture conditions with doxycycline for 14 days. Compared with the doxycycline-only control culture, there were around 2.5-fold more AP-positive colonies in the Wnt3a-treated culture (Fig. 1, B-a).

To test whether β-catenin is important for reprogramming, we used CHIR (CHIR99021), a small molecule reported to simulate the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. We cultured NSCs in mESCs medium with doxycycline and with or without 1.5 μm CHIR for 14 days. Quantification of AP-positive colonies indicated that reprogramming of NSCs was 2.7 times more effective in cells treated with CHIR than without (Fig. 1, B-b).

To confirm our results, we expressed active β-catenin by tranducing constitutively activated β-catenin DNA (β-catenin 4A) into NSCs. The β-catenin 4A gene was packaged into a lentivirus particle enabling us to introduce it into iPSCs-derived NSCs. Since the β-catenin 4A gene construct also contains a GFP reporter, we verified that over 90% of infected iPSCs-derived NSCs were GFP-positive (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 1, B-c, significantly more AP-positive colonies emerged in the sample overexpressing β-catenin. Thus, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway significantly enhanced the reprogramming efficiency.

In addition to the β-catenin activation assays for enhancing reprogramming, we also knocked out β-catenin gene or knocked down its expression to prove the necessity of β-catenin activity for promoting reprogramming. Treatment of NSCs with tamoxifen allows activation of Cre-ER and thereby deletion of floxed β-catenin gene. Knockdown of β-catenin expression is achieved by introducing β-catenin shRNA into NSCs using a viral delivery system. Similar results were obtained from both β-catenin deletion by tamoxifen addition and β-catenin knock down with β-catenin shRNA (Fig. 1, C-a and b). The numbers of AP-positive colonies in the β-catenin floxed and β-catenin shRNA samples were only 50 and 40%, respectively, of those in control cultures (Fig. 1, C-a and b). These results demonstrate that β-catenin is crucial for efficient reprogramming.

The Increased Reprogramming Efficiency by Wnt/β-catenin Is Not Due to Increased Total Cell Population or Activation of c-Myc

Wnt/β-catenin signaling has important effects on cell survival, proliferation, and cell fate. For example, in the central nervous system, Wnt3a mutant mice exhibit underdevelopment of the hippocampus due to inadequate cell proliferation (27). Conversely, continuous Wnt signaling results in expansion of the brain (28). In hESC culture, Wnt3a has been reported to stimulate cell proliferation (8). Taking these observations into account, a logical explanation for Wnt/β-catenin on reprogramming would be a gross increase in total cell number. To examine this hypothesis, we performed cell counting and a corresponding FACS analysis experiment. NSCs were seeded onto gelatin-coated plates under mESC culture conditions with or without doxycycline and with or without CHIR supplementation for 9 days. The total number of cells and SSEA1 positive population were measured during the time course. The counting results demonstrated that, without doxycycline treatment, total cell numbers had increased only slightly. However, with doxycycline, the total cell population had significantly increased in a time-dependent manner. Compared with the doxycycline-only sample, the total cell number in the CHIR-treated sample was slightly lower (Fig. 1D-a). However, FACS analysis revealed that the SSEA1-positive cell population in the CHIR-treated culture was dramatically larger than in the doxycycline-only culture. The percentage of SSEA1 positive cells at three time points was 11, 22, and 16% in the control doxycycline cultures versus 19, 34, and 33% in the CHIR-treated cultures (Fig. 1D-b). These results demonstrate that Wnt/β-catenin does not exert its effect (20) on reprogramming by increasing total cell population.

c-Myc is a downstream transcription target of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and Wnt3a has been shown to effectively enhance three-factor (OSK)-mediated iPSCs induction (20). This indicates that c-Myc might mediate the effect of Wnt/β-catenin on reprogramming. However, no detectable increase in c-Myc expression has been observed during reprogramming. We examined endogenous mouse c-Myc gene expression using NSCs derived from four (OSKM)-factor induced iPSCs in which exogenous human c-Myc gene was used to generate iPSCs. RT-PCR using primers specific for mouse c-Myc gene determined endogenous c-Myc gene expression. The β-catenin gene or β-catenin shRNA were introduced to NSCs prior to doxycycline treatment by lentiviral transduction. Western blot confirmed the expression of β-catenin in the cells (Fig. 1E-a). It is noted that without doxycycline treatment, β-catenin overexpression induced endogenous c-Myc expression whereas β-catenin knockdown reduced c-Myc expression. This is consistent with the literature that c-Myc is a downstream target of β-catenin. However, in NSCs treated with doxycycline, overexpression of β-catenin caused a decrease in endogenous c-Myc gene expression while β-catenin knockdown enhanced c-Myc gene expression (Fig. 1E-a and b). To confirm our observations, we used NSCs derived from three-factor (OSK) iPSCs lacking c-Myc to repeat the experiment but used CHIR in place of the β-catenin 4A gene to provide β-catenin activation. Consistent results were obtained: without doxycycline addition, c-Myc was induced by CHIR treatment, whereas with doxycycline treatment, c-Myc levels were suppressed by addition of CHIR (Fig. 1E-c). These data show that endogenous c-Myc gene expression is negatively correlated with β-catenin activation during the reprogramming process. Therefore, the effect of β-catenin on reprogramming efficiency is not due to activation of c-Myc gene expression.

TCF Is Involved in the Enhanced Reprogramming Effect of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

In the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway, stabilized β-catenin accumulates in the nucleus and serves as a transcriptional coactivator of the LEF/TCF family of transcription factors whose target genes regulate cell proliferation, stem cell maintenance, and differentiation. Apart from TCF, β-catenin has been reported to be able to form a complex with Oct4 and enhance its activity in the regulation of mESC self-renewal. Whether the effect of β-catenin on regulation of reprogramming is mediated through TCF family transcription factor is unclear. To determine if TCF family proteins may be involved in the β-catenin -induced reprogramming process, we used a dominant negative TCF4 (DN-TCF4) gene to interfere with Wnt/β-catenin function to determine if reprogramming was affected. Both β-catenin and DN-TCF4 were introduced into NSCs by lentiviral transduction. The expression of β-catenin and DN-TCF4 were confirmed by Western blot (data not shown). The ability of DN-TCF4 to block Wnt/β-catenin signaling in NSCs was evaluated by Tcf-luciferase reporter assay, and endogenous Axin2 gene expression using RT-PCR and qRT-PCR (data not shown). Identical NSCs were plated into gelatin-coated plates to initiate reprogramming. We found that overexpression of β-catenin stimulated iPSCs induction and such induction was partially inhibited by DN-TCF4 expression (Fig. 2A). Because DN-TCF4 is a mutant form of TCF4 with an N-terminal truncation that renders it unable to bind to β-catenin, it may block endogenous Tcf family proteins binding their target sites. These data demonstrated that β-catenin might enhance iPS cell induction through Tcf family proteins.

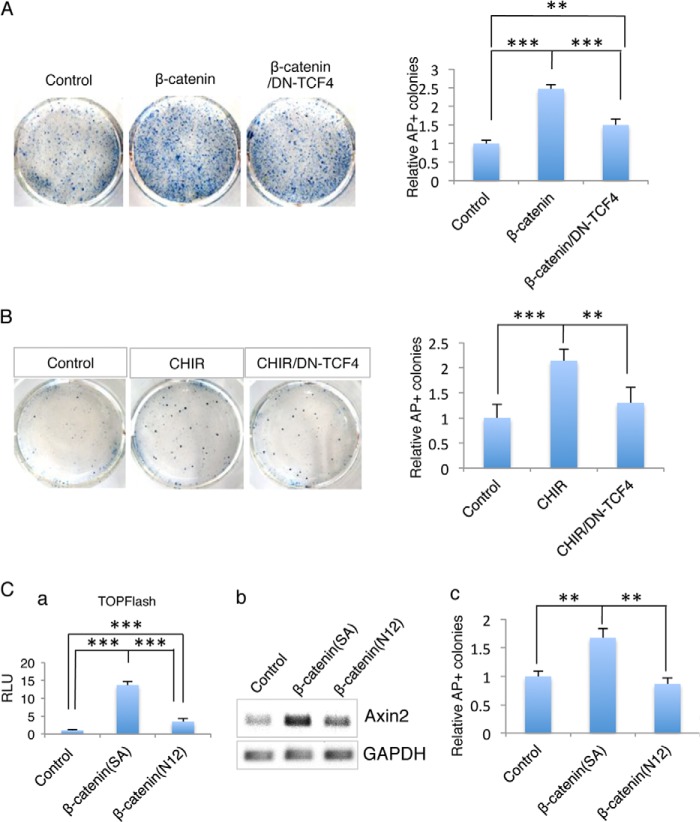

FIGURE 2.

The effect of β-catenin on regulation of reprogramming efficiency involves Tcf family protein(s). A, effect of β-catenin and DN-Tcf4 on iPSCs induction. Right panel, quantification of AP-positive colonies from A represents the fold change in the number of AP-positive colonies compared with the control sample (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; ***, p < .01). B, DN-Tcf4 inhibits iPSCs generation induced by the GSK3β inhibitor CHIR. The same experimental strategy as used in A but using CHIR instead of the β-catenin 4A gene for β-catenin activation (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; **, p < .05). Right panel, quantification of AP-positive colonies from B. C, mutant β-catenin gene (β-catenin N12), which cannot bind Tcf, fails to enhance iPSCs generation. The activity of mutant β-catenin was determined by TOPFlash luciferase assay in NSCs. Compared with control vector, mutant β-catenin was unable to active the TCF activation (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; **, p < .05) (a). Its ability to activate expression of the endogenous target gene Axin2 was determined by RT-PCR (b). The activity of β-catenin on iPSCs induction is indicated by the fold change of AP-positive colonies (c) (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; ***, p < .01).

In a separate experiment that follows the same strategy but using CHIR instead of the β-catenin 4A gene, the effect of CHIR on enhancing iPS cell induction was partially blocked by DN-TCF4 (Fig. 2B). This result confirmed our previous results, that DN-TCF4 can partially block the effect of β-catenin signaling on reprogramming promotion.

To further validate our results, we utilized a mutant β-catenin gene (β-catenin N12) in which the TCF-binding site (C terminus) was truncated to block the binding of β-catenin to TCF. The mutant β-catenin does not activate the Tcf-luciferase reporter (Fig. 2C-a). Through nucleofection (Amaxa Nucleofector technology), control, β-catenin (β-catenin SA) and mutant β-catenin (β-catenin N12) genes were delivered into NSCs. To monitor the nucleofection efficiency, GFP DNA was co-delivered into the NSCs. More than 90% of the NSCs were GFP positive (data not shown), and qRT-PCR demonstrated that the activation of endogenous β-catenin target gene Axin2 was impaired by the β-catenin mutant gene (Fig. 2C-b). As expected, the mutant β-catenin gene led to a substantial reduction in AP-positive colonies compared with the control and β-catenin samples (Fig. 2C-c). These results are consistent with our previous finding that the effect of β-catenin on reprogramming is at least partially mediated by a TCF family protein.

β-Catenin Regulates Reprogramming Efficiency Especially at the Initial Stages of Reprogramming

Reprogramming is a relatively long process that includes many regulatory steps. During the reprogramming process, differentiation gene expression is inhibited while genes related to stemness are gradually activated. Many forms of epigenetic regulation also occur during reprogramming. To investigate the mechanism behind β-catenin's effect on regulation of reprogramming efficiency, we asked two questions: when does Wnt/β-catenin have the most definite effect for promoting iPSCs generation during the reprogramming process, and what cascade mediates this effect?

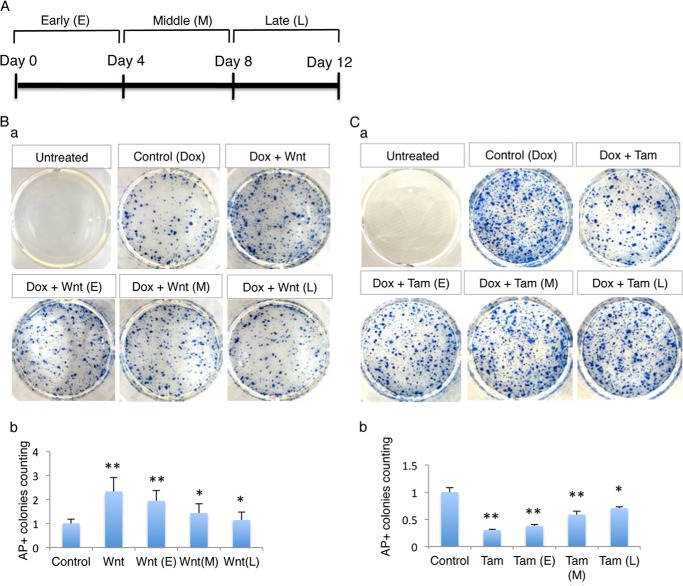

We first examine at what stage Wnt3a has the most effective promotion effect for iPSCs induction. A recombinant human Wnt3a protein was added at different time points throughout the reprogramming process. The entire process (12 days) was divided into three stages: the early stage spanned days 1–4, the middle stage days 5–8, and the late stage days 9–12 (Fig. 3A). Endogenous Oct4 gene was activated at the late stage of reprogramming while SSEA1 positive progenitor cell emerged at the middle stage. Culture medium was changed every 2 days. Notably, the greatest number of AP-positive colonies (2.7-fold increase) appeared in samples that were treated with Wnt3a for the full 12 days (Fig. 3B-a and b). In comparing the remaining three samples treated with Wnt3a during the different reprogramming stages, the largest increase in AP-positive colonies was observed at the early stage in samples treated with Wnt3a only for 4 days; 2.6-fold versus 2.4-fold for the middle stage and 2.1-fold for the late stage relative to the control culture. Notably, there was a similar degree of fold increase of AP-positive colonies between the early stage and the full process, and consequently there was no significant difference between these two samples (Fig. 3B-a and b). These results indicate that the greatest effect of Wnt/β-catenin signaling on reprogramming occurs especially during the early stage of reprogramming and that the early treatment with Wnt3a was sufficient for converting differentiated cells to a pluripotent state.

FIGURE 3.

β-Catenin enhances reprogramming efficiency at the initial stage of the reprogramming process. A, scheme of the experimental design. The reprogramming process was divided into three stages. The early stage spanned from day one to day four, the middle stage began on day 5 and ended at day 8, and the late stage began on day 9 and ended at day 12. Doxycycline was added to the medium throughout the reprogramming process. Wnt3a or tamoxifen was supplied throughout the whole reprogramming process or at d0, d4, or d9 and lasted for 4 days. Medium was changed every 2 days. B, Wnt3a treatment at the early stage of reprogramming enhances iPSCs induction more than treatment at other stages. The iPSCs colonies were detected by AP staining (a). The quantification of AP-positive colonies is shown (b) (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; **, p < .05). C, β-catenin is required for reprogramming preferentially at the early stage of reprogramming. β-Catenin gene was deleted at different reprogramming stages and induced iPSCs colonies were determined by AP staining (a). The efficiency of reprogramming is determined by quantification of AP-positive colonies (b) (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; **, p < .05).

To validate this observation, we applied tamoxifen at various reprogramming states to remove β-catenin. Tamoxifen was added at either day 1, 4, or 9 and maintained for 4 days. Tamoxifen was also added and maintained for the entire 12 days as a control. Consistent with our results from the Wnt3a treatment assay, β-catenin deletion resulted in a reduction in AP-positive colonies. The most severe decrease was noted in cultures with β-catenin deleted during the first 4 days and for the full 12 days (Fig. 3C-a and b). LacZ staining revealed that the percentage of cells carrying a deletion of β-catenin induced by tamoxifen was very similar at the different stages (data not shown). This result further confirms that β-catenin functions primarily during the initial stage of reprogramming.

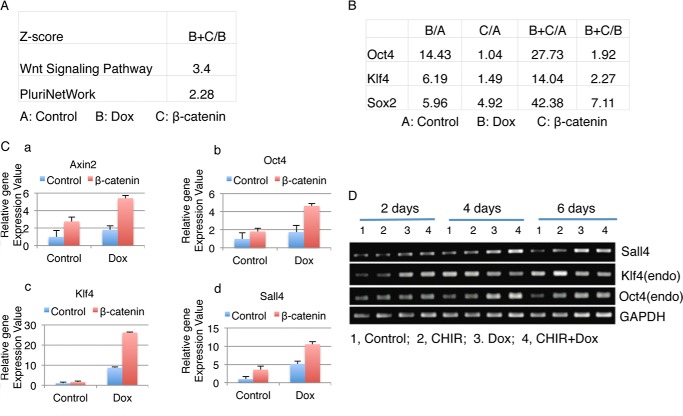

β-Catenin Functions Together with the Reprogramming Factors to Regulate Expression of Pluripotency Network

We next examined what cascades were induced by Wnt/β-catenin signaling at the initial reprogramming stage. To determine this, we examined the gene expression profiles during early reprogramming. We performed microarray analysis using NSCs samples transduced with β-catenin lentivirus and/or treated with doxycycline. The Z score analysis revealed that, in comparison to the doxycycline-only treated sample, the sample with both β-catenin and doxycycline led to enhanced Wnt signaling (Z score 3.4) and pluripotent network pathway expression (Z score 2.28) (Fig. 4A). Pluripotency-related genes such as Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 expression were increased in the β-catenin with doxycycline sample versus the doxycycline-only sample by 1.9-, 7.1-, and 2.3-fold, respectively (Fig. 4B). Quantitative RT-PCR further confirmed that in the doxycycline-treated reprogramming NSC culture, β-catenin not only activates the expression of canonical Wnt target genes such as Axin2, but also further activated expression of endogenous pluripotency genes such as Oct4, Klf4, and Sall4 (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Endogenous core stemness genes (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Sall4) and the pluripotent network were induced by β-catenin in reprogramming cells. A, signaling pathway analysis of microarray data reveals that the pluripotency network and Wnt signaling are further activated by overexpression of β-catenin in reprogramming. Total RNA from NSCs overexpressing reprogramming factors, NSCs overexpressing β-catenin, treated with doxycycline, or a combination of doxycycline treatment and β-catenin overexpression, were used for microarray analysis. B, microarray data reveals that β-catenin overexpression plus doxycycline treatment further induced Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4 expression as compared with the doxycycline treatment-only sample. C, quantitative PCR analysis of expression levels of candidate endogenous target genes. D, time-course analysis of expression of Sall4, Klf4, and Oct4 using RT-PCR. NSCs were treated with CHIR, doxycycline (Dox), or both CHIR and doxycycline (CHIR+Dox) for 2, 4, or 6 days. Untreated NSCs were used as a control. The expression levels of endogenous Sall4, Klf4, Oct4, and GAPDH were determined by RT-PCR using endogenous gene-specific primers.

To confirm our observations, we performed a time-course assay and applied CHIR to activate β-catenin. NSCs were treated with doxycycline and with or without CHIR for two, four and 6 days. As shown in Fig. 4D, endogenous Klf4 expression was detected as early as 2 days in the doxycycline plus CHIR culture. Compared with the doxycycline-only sample, Sall4 and endogenous Oct4 showed highly induced expression in the day 4 sample. At day 6, no significant difference was observed in Sall4 and endogenous Oct4 gene expression between the doxycycline-only and doxycycline-plus CHIR samples (Fig. 4D). These data further demonstrate that β-catenin genetically interacts with the “4 factors” to direct early activation of endogenous key stemness genes.

β-Catenin Interacts with Oct4, Klf4, and Sox2

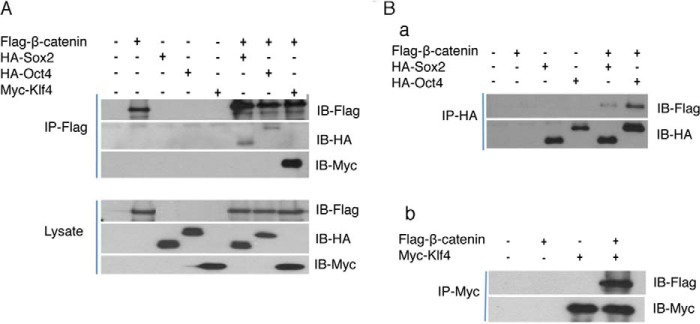

Our results indicate that β-catenin functions together with 4 reprogramming factors to promote activation of key endogenous pluripotent genes and their network. β-Catenin is a transcription co-activator and has been shown to binds to several transcription factors including Tcf. Previous experiments also suggested that β-catenin may interact with Klf4 and Oct4 (12, 29). To verify that β-catenin can physically interact with reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4, we performed a co-immunoprecipitation (IP) assay. The β-catenin expression construct was co-transduced into 293T cells along with constructs coding for Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4. As indicated in Fig. 5, the expression of β-catenin and Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 in the cells were confirmed by Western blot. Immunoprecipitation of Flag-tagged β-catenin can pull down Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4 (Fig. 5A). In addition, immunoprecipitate of Oct4, sox2, and Klf4 can also pull down β-catenin (Fig. 5B). These results demonstrated that β-catenin associated with the reprogramming factor Klf4, Oct4, and Sox2.

FIGURE 5.

β-Catenin interacts with transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4. A DNA construct encoding Flagged β-catenin 4A was co-transfected with constructs coding for HA-tagged Oct4, Sox2, or Myc-tagged Klf4 DNA into 293 T cells for 48 h. Interactions between β-catenin and Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 were determined by co-immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. A, β-catenin 4A was immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag antibody. The associated Oct4 or Sox2 proteins were determined by Western blot using anti-HA antibody. Klf4 expression was detected using anti-Myc antibody. B, Oct4 or Sox2 was immunoprecipitated using anti-HA antibody (a), and Klf4 was immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibody (b). β-Catenin that associates with these two proteins was determined by Western blot using anti-Flag antibody.

Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin/TCF Signaling May Not Be Required for iPSCs Self-renewal

Our data demonstrate that β-catenin plays a critical role in regulation of reprogramming. Aside from TCF, β-catenin also interacts with Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 to stimulate endogenous expression of core stemness genes as well as activate pluripotent network pathways. β-Catenin has been shown to form a complex with Oct4 in a TCF-independent manner to strengthen Oct4 activity in mESCs (12). As a result, we asked if β-catenin have the same crucial function in pluripotent stem cell self-renewal as they do in reprogramming.

To answer this question, we used β-catenin iPSCs as a tool to delete the β-catenin gene by floxing and then examine the requirement of β-catenin for pluripotent stem cell self-renewal. A β-catenin knock-out (KO) iPSC line was obtained by first treating β-cateninloxP/loxP-Cre iPSC line A12 with tamoxifen for 4 days, then isolating single β-catenin KO iPSCs onto 96-well feeder plates by using FACS. After 2 weeks of culture, individual colonies were isolated and analyzed. Based on LacZ staining (data not shown) and immunoblotting results (Fig. 6A-a, b), we obtained β-catenin KO iPSCs sub colonies A12/2 and A12/13 in which no β-catenin protein was detected. SSEA1/β-catenin double immunostaining showed no significant differences between KO β-catenin iPSCs and their wild-type mother β-catenin iPSCs (Fig. 6A-a). Furthermore, SSEA1 expression showed β-catenin deficiency did not impair iPSCs self-renewal (Fig. 6A-a). RT-PCR data reinforced our AP and SSEA1 staining results by showing no considerable difference between wild-type iPSCs and daughter β-catenin KO iPSCs in the expression of the core stemness gene Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, or Rex1 (Fig. 6A-c). These results suggest that β-catenin is not required for iPSCs self-renewal and stemness maintenance.

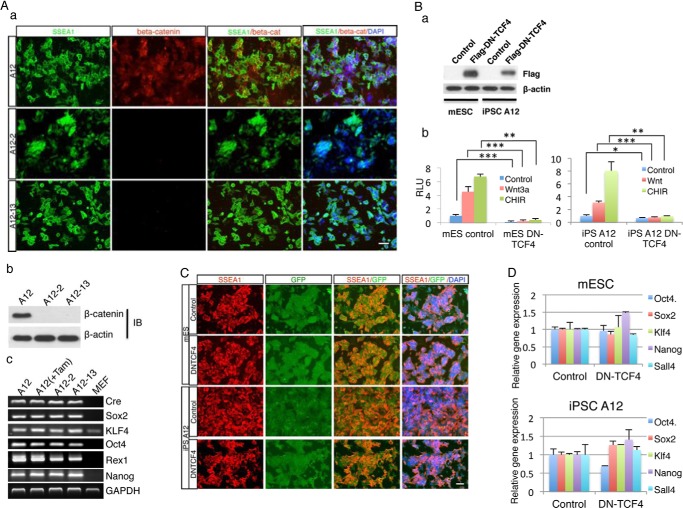

FIGURE 6.

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is not required for pluripotent stem cell self-renewal. Deletion of β-catenin in iPSCs or expression of a dominant negative TCF4 gene does not perturb self-renewal of pluripotent stem cells. A, iPSCs maintain self-renewal capacity upon β-catenin deletion. β-Catenin was deleted by tamoxifen-induced Cre-mediated recombination in two daughter iPSC lines. Expression of SSEA1 (green) and β-catenin (red) was determined by immunostaining, and the nucleus (blue) was shown by DAPI staining (a). Western blot confirms that β-catenin is absent in floxed β-catenin iPSC lines (b). Expression of stemness-related genes in these cell lines, and MEFs is determined by RT-PCR (c). B, expression of a dominant negative mutant of TCF4 (DN-TCf4) does not impair pluripotent stem cell self-renewal. DN-TCF4 DNA was introduced into mESCs and iPSCs by infections with lentiviruses, which co-express a GFP marker. Through FACS of GFP-positive cells, purified mESCs and iPSCs expressing DN-TCF4 were obtained. Western blot assay shows that DN-TCF4 DNA is introduced into mESCs or iPSCs (a). The activity of DN-TCF4 on Tcf-mediated transcription in both mESCs and iPSCs is determined by a TOPFlash luciferase reporter assay. Tcf-mediated transcription is stimulated by Wnt3a or the GSK3β inhibitor CHIR (n = 3; error bars indicate S.D.; *, p < .1, **, p < .05, ***, p < .01) (b). C, expression of the pluripotency marker SSEA1 in GFP-positive DN-TCF4-expressing mESCs, and iPSCs are shown by immunostaining. D, expression of major stemness genes in DN-TCF4-expressing mESCs and iPSCs is determined by qRT-PCR. Statistical analysis shows no significant difference between control and DN-TCF4-treated sample in both mESC and iPSC groups.

To further demonstrate that Wnt/β-catenin/TCF signaling might not be necessary for pluripotent stem cell maintenance, we performed an experiment to block β-catenin function in pluripotent stem cells by using the expression of a dominant negative mutant of TCF4 (DN-TCF4). A DN-TCF4 expression construct was transduced into mESCs and iPSCs through lentiviral infection. GFP was used as a selection marker and we were able to use FACS to obtain pure mESCs and iPSCs populations that contained the DN-TCF4 construct. Immunoblotting and TOP Flash luciferase reporter assays validated that the DN-TCF4 gene was successfully introduced into the mESCs and iPSCs and that it blocked β-catenin activity stimulated by Wnt3a or a GSK3β inhibitor (Fig. 6B-a and -b). Compared with control cultures, neither SSEA1 staining nor stemness gene expression showed any remarkable difference in DN-TCF4-transfected mESCs and β-cateninloxp/loxp iPSCs (Fig. 6, C and D). These results further strengthen our observation that the canonical Wnt/β-catenin/TCF signaling pathway is not required for pluripotent stem cell self-renewal. Furthermore, our data are also consistent with recent reports indicating that β-catenin is not required for ESCs stemness self-renewal (14–16).

DISCUSSION

The Various Mechanisms of β-Catenin and c-Myc in Enhancing Reprogramming

Both β-catenin and c-Myc expression produced high reprogramming efficiencies. In addition to generating more iPSCs colonies, a high percentage of real iPSCs colonies induced by β-catenin resembled 3 factor (OSK)-induced iPSCs (20), whereas the c-Myc-induced iPSCs colonies contained a high percentage of non-ES-like colonies. As a well-known oncogene, c-Myc has a set of target genes largely distinct from those of Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4, and increases the probability of reprogramming by accelerating the cell cycle (30, 31). Unfortunately, the tumorigenicity of c-Myc increases the frequency of transformed cells during iPSCs generation, leading to a greater risk of tumor formation by established iPSCs (32). In contrast, as demonstrated in the present study, iPSCs generation by Wnt/β-catenin signaling occurs through early promotion of endogenous pluripotent gene expression as well as through activation of the pluripotent network pathway. In the reprogramming process, β-catenin suppresses endogenous c-Myc expression. As a result, the iPSCs induced by β-catenin might have less oncogenic/tumorigenic potential. This is important for promoting the clinical applications of iPSCs technology.

The expression of c-Myc unexpectedly negatively correlates with β-catenin activation during iPS cell indution. This could be due to that β-catenin binds to other transcription factor Oct4, Klf4, and forming new transcription factor complex. The transcriptional factor complex that activates c-Myc expression is not formed.

The Differential Roles of β-Catenin in Reprogramming and Self-renewal Might Be Due to the Complexity of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling and Its Cellular Context, Developmental Stage, and Dosage-dependent Aspects

While β-catenin is crucial for reprogramming, we showed that it is not required for pluripotent stem cell maintenance. Why is β-catenin needed for just the first of these two related pluripotency events? Our results may shed some light on this important question. The mechanism of β-catenin's role in promoting reprogramming was determined to be through activation of the endogenous pluripotency network pathway. Furthermore, we found that β-catenin activation occurs at an early reprogramming stage, since the highest percentage of colonies was obtained in the early Wnt3a treatment sample. In the middle and late stage Wnt3a-treated samples, β-catenin's effect was reduced in a time-dependent manner. Our time-course CHIR-treatment experiment for endogenous pluripotent gene induction further demonstrated how Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates the reprogramming process. An increase in endogenous Klf4 expression was observed in samples treated with CHIR for 2 days, whereas Oct4 and Sall4 were strongly induced in the four-day CHIR-treatment sample. In the 6-day CHIR-treatment sample, no significant difference was observed between the control and CHIR-treated samples. This highlights the fact that Wnt/β-catenin's signaling effect on endogenous pluripotent gene stimulation is transient, occurring only at the initial reprogramming stage. It seems that the function of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is to help establish the pluripotent state in differentiated cells. Once the pluripotent state is established by endogenous pluripotency gene expression, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is no longer required. In essence, the effect of Wnt/β-catenin signaling resembles the use of a key to unlock a door. Once the door is unlocked, the key is no longer required and the pluripotent state can be maintained by existing cellular machinery.

The differential requirements for Wnt/β-catenin signaling during reprogramming also highlight the complexity of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and its dependence on cellular context, developmental stage, and molecular dosage. In differentiated cells, the endogenous pluripotent genes are silent and the chromatin condensed. In this context, with the help of reprogramming factors, Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays a critical role in reverting differentiated cells to pluripotent stem cells. However, once the pluripotent state is established, activation of endogenous pluripotent genes, and uncoiling of the chromatin structure occurs, making further Wnt/β-catenin signaling unnecessary for maintenance of stem cell function.

Another example of how the effects of Wnt/β-catenin signaling change depending on cellular context can be seen in regards to c-Myc expression. When the four reprogramming factors (OKSM) are not used, β-catenin positively regulates c-Myc expression. However, if the four reprogramming factors are simultaneously activated, c-Myc expression is suppressed by Wnt/β-catenin. In addition, the application of CHIR for reprogramming enhancement demonstrates the dosage-dependent aspect of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Unlike Marson et al., who were unable to reproduce the positive effect of Wnt/β-catenin on reprogramming efficiency by using a GSK3β inhibitor, we found that CHIR could replace a Wnt3a or a β-catenin gene construct to obtain consistent iPSCs generation. This is possibly due to our use of a lower dosage of CHIR. GSK3 is known to have numerous substrates and GSK3β inhibitors have a much broader effect than on just β-catenin (33) (34). Interestingly, we also found that CHIR could inhibit iPSCs derived NSCs proliferation at normal dosages, but not at the same dosage as is used in mESC culture. However, if we reduced the dosage of CHIR, its inhibitory effect was released but CHIR still retained its function on reprogramming, providing us with similar results as when Wnt3a or β-catenin DNA was used. In summary, the specific cellular environment and the interaction of Wnt/β-catenin signaling with other spatial or temporal factors must affect the outcome of signaling. Thus, depending on the context, Wnt signaling may have different, and sometimes opposite, effects in the same cell. Further studies are warranted to determine if these roles reflect instructive or permissive functions.

The Core Endogenous Pluripotent Genes Function as Reprogrammers, and the Effect of Wnt/β-Catenin Is to Promote but Not Open the Reprogramming Process

In previous fusion-induced somatic cell reprogramming experiments, Wnt/β-catenin signaling was postulated by Lluis and co-workers to function as an opening reprogrammer that already exists in pluripotent stem cell nuclei to enhance the conversion of somatic cells, because the effect of Wnt3a was observed only when ESCs were pretreated with Wnt3a or treated immediately after fusion (19). If somatic cells were pretreated with Wnt3a, no improvement in reprogramming occurred. This is confirmed to some degree by our experiments. Our data show that, without activation of reprogramming factors, Wnt3a/β-catenin activation is not able to revert differentiated cells to iPSCs. This means that Wnt3a cannot work alone for effective conversion of differentiated cells to a pluripotent state, consistent with Lluis's conclusion. However, with the help of ectopic reprogramming factors (Oct4, Sox, and Klf4), β-catenin can promote endogenous core stemness genes and activation of the pluripotent network pathway at the early reprogramming stage, leading to enhanced iPS cell production. These reprogramming factors (OSK) are also important transcription factors for the establishment and/or maintenance of the pluripotent state during early embryonic development. Through co-occupancy of a large set of pluripotency gene promoters and enhancer regions, Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 play pivotal roles in ESC self-renewal and pluripotency. Thus, the reprogrammers that researchers have been trying to pinpoint might in fact be Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4. The function of β-catenin might be not to open the reprogrammers but rather to enhance the activity of OSK. The interaction of β-catenin with the reprogramming factors (OSK) might help them bind to their endogenous promoters to increase transcription or help loosen the chromatin structure and facilitate access of the reprogramming factors to their target sequences. Another possibility is that this interaction might also establish the precise balance or amount of each transgene activation. Activation of all of these cascades raises reprogramming machinery efficiency, resulting in continuous establishment of a pluripotent state.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that β-catenin is required for somatic reprogramming to pluripotency but not required for pluripotency maintenance. Wnt/β-catenin enhances iPSCs induction at early stage of reprogramming and it does not function through Wnt target gene c-Myc.

The interaction of β-catenin with Tcf is important for β-catenin s's function in iPSCs induction. In addition, β-catenin interacts with Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4, respectively. In the reprogramming process, β-catenin further enhances expression of pluripotency-related genes. Such studies will allow us to use small molecules that stimulate Wnt signaling to enhance iPSCs induction to facilitate clinical application of iPSCs in the future.

Acknowledgment

We thank Hongzhen Yang for critically reading the manuscript.

This research was supported by a grant from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (RB1-01353).

- GSK

- glycogen synthase kinase

- TCF

- T-cell factor

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- iPSC

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- PEI

- polyethylenimine

- LIF

- leukemia-inhibitory factor

- NSC

- neural stem cell

- NS

- neurosphere

- AP

- alkaline phosphatase

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lu W., Yamamoto V., Ortega B., Baltimore D. (2004) Mammalian Ryk is a Wnt coreceptor required for stimulation of neurite outgrowth. Cell 119, 97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubinfeld B., Albert I., Porfiri E., Fiol C., Munemitsu S., Polakis P. (1996) Binding of GSK3β to the APC-β-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly. Science 272, 1023–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aberle H., Bauer A., Stappert J., Kispert A., Kemler R. (1997) β-Catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 16, 3797–3804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Logan C. Y., Nusse R. (2004) The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 781–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Behrens J., von Kries J. P., Kühl M., Bruhn L., Wedlich D., Grosschedl R., Birchmeier W. (1996) Functional interaction of β-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature 382, 638–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Molenaar M., van de Wetering M., Oosterwegel M., Peterson-Maduro J., Godsave S., Korinek V., Roose J., Destrée O., Clevers H. (1996) XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates β-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 86, 391–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van de Wetering M., Cavallo R., Dooijes D., van Beest M., van Es J., Loureiro J., Ypma A., Hursh D., Jones T., Bejsovec A., Peifer M., Mortin M., Clevers H. (1997) Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell 88, 789–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sato N., Meijer L., Skaltsounis L., Greengard P., Brivanlou A. H. (2004) Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat. Med. 10, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cartwright P., McLean C., Sheppard A., Rivett D., Jones K., Dalton S. (2005) LIF/STAT3 controls ES cell self-renewal and pluripotency by a Myc-dependent mechanism. Development 132, 885–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. He T. C., Sparks A. B., Rago C., Hermeking H., Zawel L., da Costa L. T., Morin P. J., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. (1998) Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science 281, 1509–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelly K. F., Ng D. Y., Jayakumaran G., Wood G. A., Koide H., Doble B. W. β-Catenin enhances Oct-4 activity and reinforces pluripotency through a TCF-independent mechanism. Cell Stem Cell 8, 214–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Otero J. J., Fu W., Kan L., Cuadra A. E., Kessler J. A. (2004) β-Catenin signaling is required for neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Development 131, 3545–3557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lyashenko N., Winter M., Migliorini D., Biechele T., Moon R. T., Hartmann C. (2011) Differential requirement for the dual functions of beta-catenin in embryonic stem cell self-renewal and germ layer formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 753–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yi F., Pereira L., Hoffman J. A., Shy B. R., Yuen C. M., Liu D. R., Merrill B. J. Opposing effects of Tcf3 and Tcf1 control Wnt stimulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 762–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miki T., Yasuda S. Y., Kahn M. (2011) Wnt/β-catenin signaling in embryonic stem cell self-renewal and somatic cell reprogramming. Stem Cell Rev. 7, 836–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., Narita M., Ichisaka T., Tomoda K., Yamanaka S. (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131, 861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu J., Vodyanik M. A., Smuga-Otto K., Antosiewicz-Bourget J., Frane J. L., Tian S., Nie J., Jonsdottir G. A., Ruotti V., Stewart R., Slukvin II, Thomson J. A. (2007) Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lluis F., Pedone E., Pepe S., Cosma M. P. (2008) Periodic activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling enhances somatic cell reprogramming mediated by cell fusion. Cell Stem Cell 3, 493–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marson A., Foreman R., Chevalier B., Bilodeau S., Kahn M., Young R. A., Jaenisch R. (2008) Wnt signaling promotes reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 3, 132–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wei Z., Yang Y., Zhang P., Andrianakos R., Hasegawa K., Lyu J., Chen X., Bai G., Liu C., Pera M., Lu W. (2009) Klf4 interacts directly with Oct4 and Sox2 to promote reprogramming. Stem Cells 27, 2969–2978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brambrink T., Foreman R., Welstead G. G., Lengner C. J., Wernig M., Suh H., Jaenisch R. (2008) Sequential expression of pluripotency markers during direct reprogramming of mouse somatic cells. Cell Stem Cell 2, 151–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Niwa H., Yamamura K., Miyazaki J. (1991) Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108, 193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takao Y., Yokota T., Koide H. (2007) Beta-catenin up-regulates Nanog expression through interaction with Oct-3/4 in embryonic stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 353, 699–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang P., Andrianakos R., Yang Y., Liu C., Lu W. (2010) Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) prevents embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation by regulating Nanog gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9180–9189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hockemeyer D., Soldner F., Cook E. G., Gao Q., Mitalipova M., Jaenisch R. (2008) A drug-inducible system for direct reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 3, 346–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee S. M., Tole S., Grove E., McMahon A. P. (2000) A local Wnt-3a signal is required for development of the mammalian hippocampus. Development 127, 457–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lie D. C., Colamarino S. A., Song H. J., Désiré L., Mira H., Consiglio A., Lein E. S., Jessberger S., Lansford H., Dearie A. R., Gage F. H. (2005) Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature 437, 1370–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Evans P. M., Chen X., Zhang W., Liu C. (2010) KLF4 interacts with β-catenin/TCF4 and blocks p300/CBP recruitment by β-catenin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 372–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim J., Chu J., Shen X., Wang J., Orkin S. H. (2008) An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell 132, 1049–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim J., Woo A. J., Chu J., Snow J. W., Fujiwara Y., Kim C. G., Cantor A. B., Orkin S. H. (2010) A Myc network accounts for similarities between embryonic stem and cancer cell transcription programs. Cell 143, 313–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Okita K., Ichisaka T., Yamanaka S. (2007) Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 448, 313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Doble B. W., Woodgett J. R. (2003) GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1175–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu D., Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci 35, 161–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]