Background: Proinflammatory chemokines released by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) play a critical role in vascular inflammation.

Results: Promoting protein kinase C-δ (PKCδ) translocation or inhibition of NF-κB pathway diminishes proinflammatory chemokine production.

Conclusion: PKCδ regulates proinflammatory chemokine expression through cytosolic interaction with the NF-κB subunit p65, thus modulating inflammation.

Significance: Learning how PKCδ regulates proinflammatory chemokine expression is crucial for understanding vascular inflammation.

Keywords: Chemokines, Gene Expression, Inflammation, Protein-Protein Interactions, Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells, Nuclear Factor κ-Light Chain Enhancer of Activated B Cells (NF-κB), Protein Kinase C-δ (PKCδ)

Abstract

Proinflammatory chemokines released by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) play a critical role in vascular inflammation. Protein kinase C-δ (PKCδ) has been shown to be up-regulated in VSMCs of injured arteries. PKCδ knock-out (Prkcd−/−) mice are resistant to inflammation as well as apoptosis in models of abdominal aortic aneurysm. However, the precise mechanism by which PKCδ modulates inflammation remains incompletely understood. In this study, we identified four inflammatory chemokines (Ccl2/Mcp-1, Ccl7, Cxcl16, and Cx3cl1) of over 45 PKCδ-regulated genes associated with inflammatory response by microarray analysis. Using CCL2 as a prototype, we demonstrated that PKCδ stimulated chemokine expression at the transcriptional level. Inhibition of the NF-κB pathway or siRNA knockdown of subunit p65, but not p50, eliminated the effect of PKCδ on Ccl2 expression. Overexpressing PKCδ followed by incubation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate resulted in an increase in p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation and enhanced DNA binding affinity without affecting IκB degradation or p65 nuclear translocation. Prkcd gene deficiency impaired p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation and DNA binding affinity in response to TNFα. Results from in situ proximity ligation analysis and co-immunoprecipitation performed on cultured VSMCs and aneurysmal aorta demonstrated physical interaction between PKCδ and p65 that took place largely outside the nucleus. Promoting nuclear translocation of PKCδ with peptide ψδRACK diminished Ccl2 production, whereas inhibition of PKCδ translocation with peptide δV1-1 enhanced Ccl2 expression. Together, these results suggest that PKCδ modulates inflammation at least in part through the NF-κB-mediated chemokines. Mechanistically, PKCδ activates NF-κB through an IκB-independent cytosolic interaction, which subsequently leads to enhanced p65 phosphorylation and DNA binding affinity.

Introduction

Vascular inflammation is a complex biological response trigged by chemical and mechanical injuries as well as by infectious stimuli. Inflammation is observed to various degrees in major cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and aortic aneurysm (1–3). A critical step of vascular inflammation is the recruitment of circulating leukocytes including monocytes and T lymphocytes into the vascular wall. The recruitment process is primarily the result of coordinated expression of vascular adhesion molecules as well as proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines (3). As a major component of the arterial wall, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)2 are critical in maintaining normal physiological functions of blood vessels as well as in modulation of pathological processes taking place in the vascular wall (4). Numerous studies have shown that VSMCs can be an important source of cytokines in the vessel wall (5–7).

Protein kinase C-δ (PKCδ), a member of the novel PKC isoforms of serine-threonine kinase, is expressed in many types of mammalian cells including cancer cells, leukocytes, and VSMCs (8). Like other members of the PKC family, PKCδ exists normally in an inactive conformation and becomes activated upon binding to diacylglycerol or its mimetic phorbol ester such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or through other molecular mechanisms such as proteolytic cleavage and/or tyrosine phosphorylation (9).

PKCδ has emerged as an important regulator of apoptosis. The proapoptotic function of PKCδ is achieved by its interaction with and phosphorylation of several key apoptotic regulators (10). For example, PKCδ associates with and phosphorylates caspase-3, promoting the apoptotic activity of the cysteine caspase during etoposide-induced apoptosis and in spontaneous apoptosis of monocytes (10). Diverse apoptosis-inducing agents including Fas ligation, etoposide, mitomycin, cytosine arabinoside, etoposide, UV light, and ionizing radiation are found to induce cleavage of PKCδ in the linker region, freeing the catalytic domain from the regulatory domain (11, 12). The free catalytic domain or fragment is thought to translocate to the nucleus and execute apoptosis (13). Consistent with this hypothesis, overexpression of the catalytic fragment in the absence of an apoptotic stimulus was sufficient to induce apoptosis in a variety of cell types (10). In contrast, several lines of studies showed a pivotal role for PKCδ in antiapoptotic function in response to cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) (14). Silencing PKCδ expression by siRNA resulted in inhibition of TNF-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation (15). Another study showed that PKCδ interacts with Smac, a mitochondrial protein. On exposure to apoptotic stimuli such as paclitaxel, this interaction is disrupted and results in the release of Smac into the cytosol and promotes apoptosis by activating caspases in the cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9 pathway. Activation of PKCδ rescues the interaction during paclitaxel exposure and suppresses paclitaxel-mediated cell death (16). What dictates whether PKCδ should exert a pro- or antiapoptotic role in a given cell is unclear.

We have shown previously that PKCδ plays a proapoptotic role during the vascular injury response (17). PKCδ expression is up-regulated in human aneurysmal aortic tissues and restenotic lesions as well as in animal models of vascular injury such as a mouse abdominal aortic aneurysm model as well as a rat carotid angioplasty model (18, 19). In mouse models of abdominal aortic aneurysm, Prkcd−/− mice are resistant to apoptosis, which is coupled with diminished proinflammatory factor expression and inflammatory cell infiltration (18). Although this mouse study indicates a role for PKCδ in modulating inflammatory signaling, the underlying mechanisms remain obscure.

NF-κB is one of the major transcription factors that control the expression of inflammatory factors (20). Activation of NF-κB is regulated by multiple distinct signaling cascades including the IκB kinase signalosome (21). In response to a variety of stimuli, IκB kinase phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32 and Ser-36, resulting in its ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation. The released NF-κB is targeted to the nucleus and binds to a κB site located in the promoter region, thereby inducing the expression of specific target genes (22). In addition to nuclear translocation of the NF-κB complex, previous studies have shown that a subunit of NF-κB, RelA/p65, is post-translationally modified by phosphorylation or acetylation, and those changes influence its DNA binding and transcriptional activity (23, 24). Although the effect of PKCδ on the NF-κB pathway has been reported, the precise mechanisms underlying PKCδ-mediated NF-κB activation remain largely unclear.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that PKCδ activation is a pivotal signal for proinflammatory chemokine expression in VSMCs. Through both in vitro and in vivo experiments, we systematically evaluated the role of PKCδ in the regulation of chemokine expression. Using chemokine (CC motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) as a chemokine prototype, we further defined the molecular mechanism of PKCδ regulation. Our data suggest that PKCδ acts through the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB in the cytosolic fraction of VSMCs that subsequently activates Ccl2 transcription.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and cell culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen. PMA was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). TAT-tagged PKCδ-specific translocation activator (ψδRACK), inhibitor (δV1-1), and control peptides were a kind gift from Dr. Daria Mochly-Rosen (Stanford University) (25). Chemicals if not specified were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell Culture

Primary VSMCs were isolated from arteries of mice or rats according to a method described previously (26). Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a 5% CO2, water-saturated incubator at 37 °C.

Adenoviral Vectors and Infection

Adenoviral vectors expressing PKCδ (AdPKCδ) and empty vector (AdNull) were constructed and purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation as described previously (27, 28). In vitro adenovirus infection was carried out as described previously (19). Briefly, VSMCs (1 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates) were infected with adenovirus (m.o.i. = 1 × 104) in DMEM containing 2% FBS overnight at 37 °C followed by starvation in DMEM containing 0.5% FBS for 24 h. The cells were then treated with PMA (1 nm) or solvent (DMSO) for the indicated periods of time. Cells were harvested and used for mRNA extraction and analysis, and medium was collected and tested by ELISA.

Microarray and Biological Functional Analyses

Following PKCδ activation by PMA, total RNA was isolated utilizing the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Genomic DNA was removed using the provided gDNA Eliminator columns. Microarray hybridization was carried out by the microarray core facility at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotech Center. Briefly, total RNA was quantified on a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE), and RNA quality was analyzed on an Agilent RNA Nano Chip (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Samples were labeled using an Ambion GeneChip® WT Expression kit (Invitrogen), and labeled cRNA was fragmented and hybridized to the GeneChip Gene 1.0 ST Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The arrays were washed and stained using a GeneChip Fluidic Station 450 and scanned using an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000. Data were extracted and processed using Affymetrix Command Console version 3.1. After correction and normalization of background using the Robust Multichip Array algorithm, differentially expressed genes were identified with a moderated t test implemented in ArrayStar software (DNAStar, Madison, WI). The list of differentially expressed genes was loaded into Ingenuity Pathway Analysis 9.0 software to perform biological functional and transcription factor analyses.

Quantitative Real Time PCR (qPCR)

2 μg of RNA was used for the first strand cDNA synthesis (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). A no-reverse transcriptase control was included in the same PCR mixtures without reverse transcriptase to confirm the absence of DNA contamination in RNA samples. qPCR primers for CCL2, CCL7, CXCL16, CX3CL1, and GAPDH were purchased from Qiagen. Triplicate 20-μl reactions were carried out in 96-well optical reaction plates using SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with gene-specific primers, and the qPCR was run in the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Amplification of each sample was analyzed by melting curve analysis, and relative differences in each PCR sample were corrected using GAPDH mRNA as an endogenous control and normalized to the level of control by using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

CCL2 ELISA

The BD OptEIA ELISA kit was purchased from BD Biosciences to measure CCL2 secreted by VSMCs according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Transfection

siRNAs to NF-κB p50 and p65 were obtained from Invitrogen. siRNA to PKCδ and its scrambled control were purchased from Qiagen. siRNA transfection was carried out as described previously (29). Briefly, VSMCs were plated onto 6-well plates in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were then transfected in Opti-MEM I medium with 10 nm siRNA for NF-κB p50, NF-κB p65, or control using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent as described by the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). At 6 h post-transfection, Opti-MEM I medium was replaced with DMEM containing 2% FBS.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (Sigma-Aldrich), and total protein was extracted. Nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were extracted using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Equal amounts of protein extract were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were then incubated with rabbit antibodies to phospho-NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology), PKCδ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology) and mouse antibodies to IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology) and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Bio-Rad). Labeled proteins were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). For quantification, optical density of secreted proteins determined using NIH ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was normalized to the loading control density.

NF-κB p65 DNA Binding Activity

An ELISA-based TransAM NF-κB p65 assay kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) was used to measure the binding activity of NF-κB to DNA in nuclear extracts according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 5 μg of nuclear protein from each sample was added to different wells in which multiple copies of the consensus binding site for NF-κB had been immobilized and incubated for 1 h at room temperature for NF-κB DNA binding. By using an antibody that is specific for NF-κB p65, the activated NF-κB subunit bound to the oligonucleotides can be detected. An HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was added to provide a sensitive colorimetric readout. The signal was quantified by reading the absorbance at 450 nm on a FlexStation 3 Benchtop Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

In Situ Proximity Ligation Assay

An in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) was performed to detect protein-protein interactions using a Duolink in situ fluorescence kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden). Briefly, treated VSMCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min followed by cell membrane permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Tissue sections were fixed for 10 min in cold acetone. The slides were washed three times with PBS, blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% BSA and normal donkey serum in PBS, and incubated with the indicated antibody pairs overnight at 4 °C. Oligonucleotide-conjugated secondary antibodies (PLA probe MINUS and PLA probe PLUS) against each of the primary antibodies were applied, and ligation and amplification were carried out to produce rolling circle products. These products were detected with fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides, and the sections were counterstained using Duolink Mounting Medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Samples were examined using a Nikon microscope (Melville, NY).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using the Pierce Classic IP kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, whole cell extract was precleared with control agarose resin for 1 h at 4 °C. The clarified supernatant was then incubated with anti-PKCδ or -p65 antibody or its isotype control overnight at 4 °C followed by a 1-h incubation with Protein A/G Plus-agarose beads. The beads were washed five times, and immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to immunoblotting.

Mouse Models of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

The generation of Prkcd target deletion in mice was described elsewhere (30). Prkcd−/− (PKCδ KO) mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates were generated by mating heterozygous pairs. Male mice (12 weeks of age) underwent a CaCl2- or elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm model as described previously (31, 32). Briefly, animals were anesthetized using a continuous flow of 1–2% isoflurane. For the CaCl2 model, the infrarenal region of the aorta was isolated and perivascularly treated with 0.5 m CaCl2 or 0.5 m sodium chloride (NaCl control) via gauze for 15 min. For the elastase model, the infrarenal region of the aorta was isolated, and temporary silk ligatures were placed at proximal and distal portions of the aorta. An aortotomy was created near the distal ligature using a 30-gauge needle, and heat-tapered polyethylene tubing (Baxter Healthcare Corp.) was introduced through the aortotomy and secured with a silk tie. The aorta was filled with saline containing 0.295 unit/ml type I porcine pancreatic elastase (Sigma) or heat-inactivated elastase solution (control) at a constant pressure of 100 mm Hg. Buprenorphine was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 0.05 mg/kg immediately after surgery. Subsequently, a 2.5% Xylocaine topical ointment was applied to the suture site. The maximum external diameter of the infrarenal aorta was measured using a digital caliper (VWR Scientific, Radnor, PA) prior to treatment and at the time of tissue harvest. At selected time points, mice were sacrificed by an overdose of isoflurane, and tissues were harvested. Tissues meant for RNA isolation were stored in RNAlater RNA Stabilization Reagent (Qiagen). Tissues meant for in situ proximity ligation assay were freshly imbedded in O.C.T. Compound (Sakura Tissue Tek, Netherlands). All frozen sections were cut to 6 μm thick using a Leica CM3050S cryostat. All animal experiments in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Protocol M02284) and performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t test or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc test was used to evaluate the statistical differences. Differentially expressed genes in microarray analysis were identified by moderated t test implemented in ArrayStar software. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

PKCδ Regulates Proinflammatory Chemokine Expression

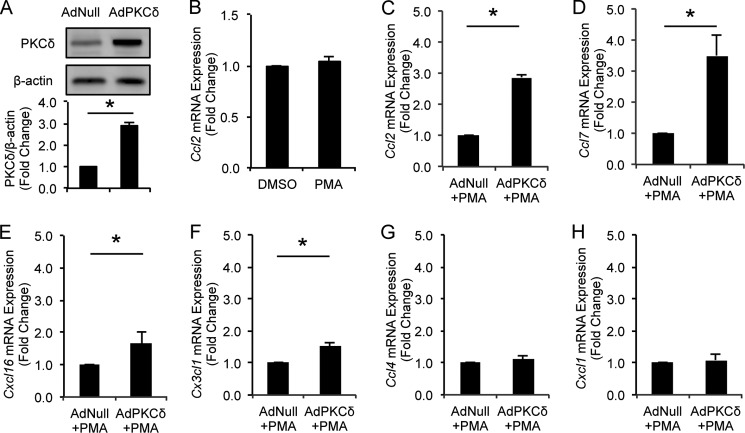

We have previously reported a 2.51 ± 0.24-fold increase in PKCδ protein in VSMCs of aneurysmal arteries (18, 33). To study the role of PKCδ in chemokine expression by VSMCs, we mimicked this pathological PKCδ up-regulation by overexpressing PKCδ in cultured arterial VSMCs to a similar level (2.88 ± 0.15-fold induction) (Fig. 1A) followed by a brief activation with a low concentration of PMA (1 nm for 6 h). At this concentration, PMA alone had no effects on Ccl2 expression (Fig. 1B). Next, we determined transcriptome profiles using microarray analysis on total RNA isolated from PKCδ-overexpressing and control VSMCs. After normalization of hybridization intensities using the Robust Multichip Array algorithm in the ArrayStar software, the average expression level of each gene was calculated from biological triplicates. Differentially expressed genes were identified with a moderated t test implemented in ArrayStar software. To analyze the biological function of the transcripts differentially regulated by PKCδ, the entirety of differentially expressed transcripts was loaded into the pathway analysis program based on the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base. Among the top five implicated disease conditions, two involve inflammation (Table 1). Indeed, 45 differentially expressed genes have known inflammatory roles. And a series of proinflammatory chemokines including Ccl2/Mcp-1, Ccl7, Cxcl16, and Cx3cl1 are among those genes.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of PKCδ on chemokine expression in VSMCs. A, VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis. B, VSMCs were incubated with PMA (1 nm) or DMSO for 6 h. Expression of Ccl2 was analyzed by qPCR. C–H, VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ followed by incubation with PMA (1 nm) for 6 h. mRNA expression levels of four up-regulated chemokines, Ccl2 (C), Ccl7 (D), Cxcl16 (E), and Cx3cl1 (F), identified by microarray analysis were confirmed by qPCR. mRNA expression levels of two unregulated chemokines, Ccl4 (G) and Cxcl1 (H), identified in microarray analysis were analyzed by qPCR. Data show the mean of independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. n = 3; *, p < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t test.

TABLE 1.

Biological function of differentially expressed genes

Differentially expressed genes in PKCδ-overexpressing and control VSMCs were loaded into Ingenuity Pathway Analysis 9.0 software to perform biological functional analyses. The table indicates names of biological functions and differentially expressed genes (first column) and the number of genes in each disease condition (second column). Inflammatory chemokines are shown in bold.

| Diseases and disorders | No. molecules |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory response | 45 |

| Ass1, Bdkrb2, Bhlhe41, Btn3a3, Ccl2, Ccl7, Cd274, Cd38, Cx3cl1, Cxcl10, Cxcl16, Ddx58, Dhx58, Ednrb, Egln3, Egr2, Fgf2, Gbp2 (includes EG:14469), Hla-C, Ifi44, Ifih1, Il18bp, Il33, Irf7, Irf9, Irgm, Isg15, Itga4, Lgals9b, Mug1 (includes others), Mx1, Nfatc2, Nr4a3, Oas1b, Olr1, Pon2, Psmb9, Psme2, Rgs2 (includes EG:19735), S1pr1, Serpinb2, Serping1, Slfn12, Sucnr1, Ube2l6 | |

| Skeletal and muscular disorders | 41 |

| Ankh, C1s, Ccl2, Ccl7, Ccne1, Ccne2, Cd274, Cd38, Cp, Cx3cl1, Cxcl10, Dusp5, Ednrb, Egr2, Fgf2, Gbp2 (includes EG:14469), Hla-C, Hla-E, Il18bp, Il33, Irf7, Irgm, Isg15, Itga4, Lgals9b, Ly6e, Mx1, Nefl, Nfatc2, Nr4a3, Psmb9, Rgs4, Rsad2, S1pr1, Serping1, Slfn12, Slfn12l, St8sia2, Ube2l6, Vamp1, Xdh | |

| Genetic disorder | 40 |

| Acpp, Ankh, Ass1, Bdkrb2, C1s, Ccl2, Ccne1, Ccne2, Cp, Cx3cl1, Cxcl10, Ddx58, Ednrb, Etv1, Gbp2 (includes EG:14469), Herc6, Hla-C, Ifi27, Ifi44, Ifit3, Il33, Irf7, Irgm, Isg15, Itga4, Lgals3bp, Ly6e, Mx1, Nefl, Nr3c2 (includes EG:110784), Parp9, Pon2, Psme2, Rsad2, Rtp4, S1pr1, Serpinb2, Serping1, Ube2l6, Xdh | |

| Inflammatory disease | 35 |

| Ankh, C1s, Ccl2, Ccl7, Cd274, Cxcl10, Ednrb, Egr2, Fgf2, Gbp2 (includes EG:14469), Hla-C, Hla-E, Ifi27, Il18bp, Il33, Irf7, Irgm, Isg15, Itga4, Lgals9b, Ly6e, Mx1, Nfatc2, Nr4a3, Psmb9, Psme2, Rsad2, S1pr1, Serpinb2, Serping1, Slfn12, Slfn12l, Tmeff2, Ube2l6, Xdh | |

| Neurological disease | 29 |

| Ccl2, Cd274, Cd38, Cp, Cx3cl1, Cxcl10, Dusp5, Ednrb, Egr2, Fgf2, Hla-E, Il18bp, Irf7, Irgm, Isg15, Itga4, Ly6e, Mx1, Ndst3, Nefl, Nfatc2, Psmb9, Rgs4, Rsad2, S1pr1, Serping1, St8sia2, Usp18, Vamp1 | |

Next, we validated expression of the chosen chemokines using qPCR. As shown in Fig. 1, C–F, PKCδ significantly increased expression of Ccl2, Ccl7, Cxcl16, and Cx3cl1 to a similar extent as observed by microarray analysis. In contrast, Ccl4 and Cxcl1, which were not among the list of target genes, were not affected by PKCδ (Fig. 1, G and H).

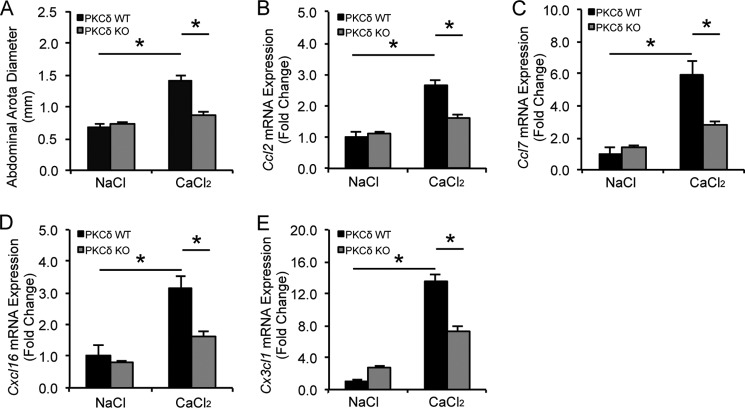

PKCδ Is Required for Chemokine Expression in Experimental Aneurysm

Next, we addressed whether PKCδ regulates chemokine expression in abdominal aortic aneurysm, a disease condition known to involve inflammation. PKCδ knock-out mice and their WT littermates were subjected to aneurysm induction by perivascular administration of CaCl2. Consistent with our previous report, PKCδ knock-outs were resistant to aneurysm induction, whereas their wild-type counterparts displayed visible aortic expansion (Fig. 2A). qPCR analysis showed a 2–14-fold increase in arterial expression of Ccl2, Ccl7, Cxcl16, and Cx3cl1 by induction of aneurysm in the wild-type mice (Fig. 2, B–E). Prkcd gene deletion eliminated or markedly diminished this chemokine up-regulation (Fig. 2, B–E), further supporting the stimulatory role of PKCδ in the regulation of chemokine expression during aneurysm pathogenesis.

FIGURE 2.

PKCδ gene deletion attenuates chemokine expression in experimental aneurysm. A, abdominal aortic diameters of PKCδ wild-type (WT) and knock-out (KO) mice were measured 42 days after NaCl or CaCl2 treatment. Total RNA was isolated from WT or KO abdominal aortic arteries 7 days after NaCl or CaCl2 treatment. Expression of selected chemokines, Ccl2 (B), Ccl7 (C), Cxcl16 (D), and Cx3cl1 (E), was analyzed by qPCR. Data show the mean of independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. n = 3–6; *, p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

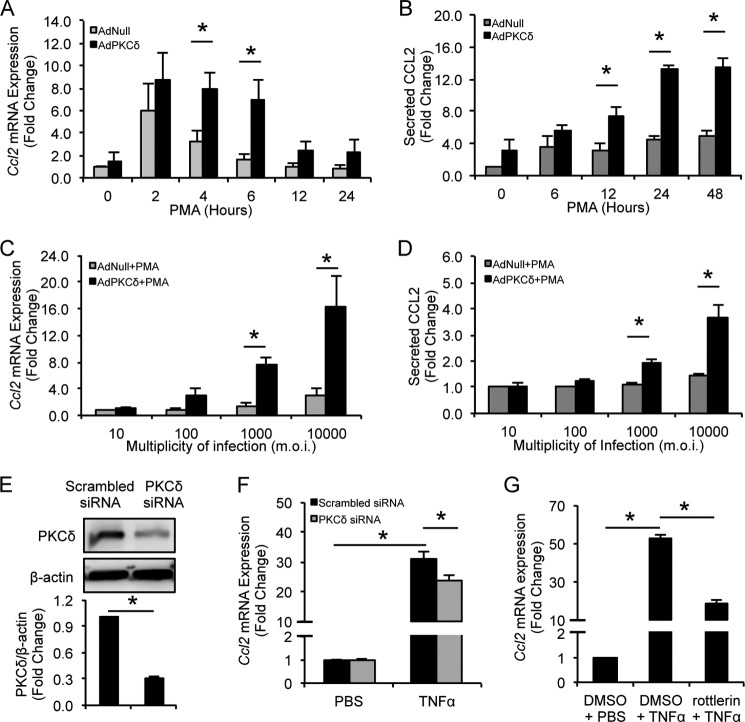

PKCδ Stimulates Ccl2 Transcription

We used CCL2, one of the critical chemokines that mediate the pathogenesis of vascular diseases (34), as a prototype to elucidate how PKCδ regulates chemokine expression. As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, overexpression/activation of PKCδ led to a rapid increase in levels of CCL2 mRNA and protein, peaking around 6 and 24 h, respectively. We also mimicked different PKCδ expression intensities by treating arterial VSMCs with increasing concentrations of adenoviruses carrying the Prkcd gene. Both CCL2 mRNA and protein responded to PKCδ in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3, C and D). Next, we knocked down endogenous PKCδ using a specific siRNA in VSMCs stimulated with TNFα, a critical inflammatory mediator implicated in the pathogenesis of aneurysm (35). PKCδ-specific siRNA reduced the PKCδ protein level by 70% compared with control (Fig. 3E). Although TNFα up-regulated Ccl2 expression in scrambled siRNA-transfected VSMCs, this proinflammatory function was significantly impaired by PKCδ knockdown (Fig. 3F). Pretreatment of VSMCs with rottlerin, a PKCδ chemical inhibitor, also significantly attenuated TNFα-induced Ccl2 production in VSMCs (Fig. 3G).

FIGURE 3.

PKCδ is critical for CCL2 production. VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104 followed by incubation with PMA (1 nm) for the indicated time (A and B) or at the indicated m.o.i. followed by incubation with PMA (1 nm) for 6 (C) or 24 (D) h. A and C, Ccl2 mRNA expression was analyzed by qPCR. B and D, level of secreted CCL2 was measured by ELISA. E, VSMCs were transfected with PKCδ-specific or scrambled siRNA for 24 h, and whole-cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis. F, PKCδ-specific or scrambled siRNA-transfected VSMCs were incubated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or PBS for 2 h, total RNAs were isolated, and levels of Ccl2 mRNA were analyzed by qPCR. G, VSMCs were treated with TNFα (20 ng/ml) in the presence of 2 μm rottlerin or DMSO for 6 h, and levels of Ccl2 mRNA were analyzed by qPCR. Data show the mean of independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. n = 3–6; *, p < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t test (A–D) and one-way ANOVA (E and F).

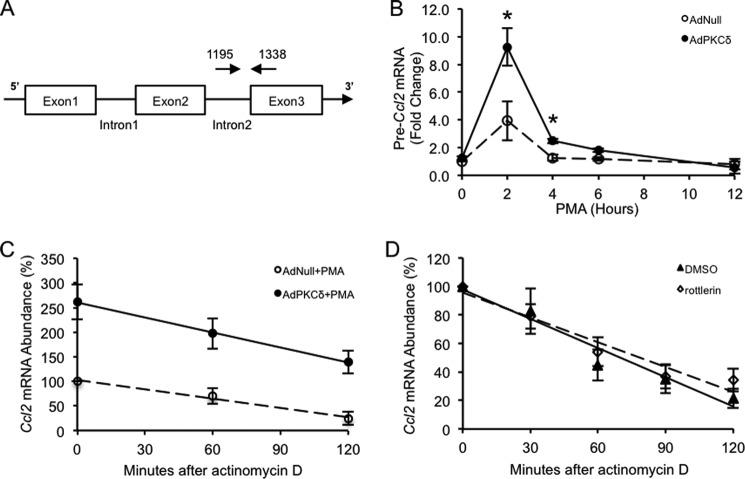

Because introns are rapidly removed from heterogeneous nuclear RNA during splicing, levels of unspliced pre-mRNA can be used to measure the rate of transcription of a given gene (36). Using a primer pair that spans the junction of Ccl2 intron 2 and exon 3 (Fig. 4A), we measured the Ccl2 transcription rate. Activation of PKCδ caused a rapid elevation in the Ccl2 transcription rate with a maximum induction of 2.35 times over the control (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Transcriptional regulation of Ccl2 gene expression by PKCδ. A, schematic of the Ccl2 gene. The exons are shown as boxes, and introns are shown as thin lines. The location of the 5′ amplification primer is shown as a rightward arrow above the second intron. The location of the 3′ primer used for PCR is shown as a leftward arrow above the third exon. B, VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104 followed by incubation with PMA (1 nm) for the indicated time. The transcription rate was determined by qPCR analysis of Ccl2 pre-mRNA with the specific primers spanning the junction of the second intron and the third exon (shown in A). C, VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104 followed by incubation with PMA (1 nm) for 6 h. Actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) was added to shut down transcription. Cells were harvested at the indicated times, total RNA was isolated, and levels of Ccl2 mRNA were analyzed by qPCR. D, VSMCs were treated with 20 ng/ml TNFα for 6 h, and actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) was then added with 2 μm rottlerin or DMSO. Cells were harvested at the indicated times, total RNAs were isolated, and levels of Ccl2 mRNA were analyzed by qPCR. Results are presented as a percentage of Ccl2 mRNA remaining over time compared with the amount before the addition of actinomycin D. Data show the mean of independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. n = 3; *, p < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t test.

To determine whether PKCδ affects the stability of Ccl2 mRNA, we measured the rate of Ccl2 mRNA degradation in VSMCs with various PKCδ activities with or without up-regulated PKCδ. As shown in Fig. 4C, overexpression of PKCδ did not alter the rate of Ccl2 mRNA degradation. Similarly, the rate of Ccl2 mRNA decay was nearly identical in cells with or without the presence of the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin (Fig. 4D). These results collectively indicate that PKCδ up-regulates Ccl2 through increasing its transcription without affecting the stability of Ccl2 mRNA in VSMCs.

NF-κB Subunit p65, but Not p50, Is Required for the Up-regulation of Ccl2 by PKCδ

Because PKCδ does not have a known DNA binding capacity, we postulated that it regulates chemokine transcription by directly or indirectly phosphorylating transcription factors. To aid identification of such downstream factors, we analyzed the PKCδ-regulated genes for potential common regulatory motifs. Results of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis 9.0 identified CDKN2A, PDX1, IRF1, STAT1, IRF3, STAT2, RB1, NF-κB, and TP53 as common transcription factors shared by multiple PKCδ-regulated genes. Among these transcription factors, NF-κB stood out as it is known to regulate each of the four PKCδ-dependent proinflammatory chemokines (Ccl2, Ccl7, Cxcl16, and Cx3cl1) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Common transcription regulators shared by PKCδ-regulated genes in VSMCs

Differentially expressed genes in PKCδ-overexpressing and control VSMCs were loaded into Ingenuity Pathway Analysis 9.0 software to perform transcription factor analyses. The table indicates names of transcription regulators (first column) and names of genes sharing a common transcription regulator (second column). Inflammatory chemokines are shown in bold.

| Transcription regulator | Target molecules |

|---|---|

| CDKN2A | Ccne1, Cenpk, Fam111a, Melk, Plagl1 |

| PDX1 | Ccl2, Cx3cl1, Dusp5, Dusp6, Fgf2, Rsad2 |

| IRF1 | Cxcl10, Gbp2, Ifih1, Ifit3, Il18bp, Irf7, Irf9, Isg15, Mx1, Psmb9, Psme2, Rsad2 |

| STAT1 | Ccne1, Cd274, Clic5, Cxcl10, Fgf2, Gbp2, Ifi27, Ifi47, Ifit3, Irf7, Irf9, Irgm, Isg15, Ly6e, Psmb9, Psme2, Rnf213, Rsad2, Serping1, Slfn12, Slfn12l, Usp18 |

| IRF3 | Ccl2, Cxcl10, Ddx58, Dhx58, Ifi44, Ifih1, Ifit3, Irf7, Isg15, Mx1, Rsad2, Usp18 |

| STAT2 | Cxcl10, Ifi27, Ifit3, Irf7, Irf9, Isg15, Mx1 |

| RB1 | Ccne1, Ccne2, Cdc6, Cenpk, Fam111a, Fgf2, Melk |

| NF-κB (complex) | Ccl2, Ccl7, Cd274, Cx3cl1, Cxcl10, Cxcl16, Dusp5, Ednrb, Fgf2, Gbp2, Hla-C, Irf7, Isg15, Olr1, Psmb9, Rsad2, Serpinb2 |

| TP53 | Ankh, Ass1, Bdkrb2, C11orf82, Ccl2, Ccne1, Ccne2, Cdc6, Cx3cl1, Dusp5, Fgf2, Irf7, Irf9, Isg15, Mx1, Serpinb2, Serping1, Sh3bgrl2 |

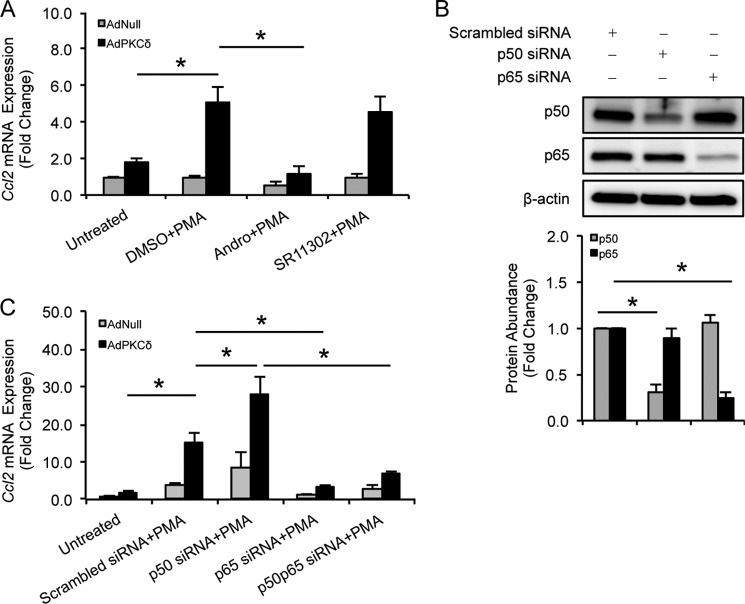

Once again, we used CCL2 as a prototype to delineate how PKCδ and NF-κB may interact in the context of chemokine regulation. Sequence analysis of the Ccl2 gene promoter region confirmed the presence of NF-κB binding motifs along with several other cis-elements including those for CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein, AP-1, Sp-1, and tonicity-response element/osmotic response element (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5A, andrographolide (15 μm), an NF-κB inhibitor (37), completely blocked Ccl2 induction by PKCδ. In contrast, SR11302 (1 μm), which is known to inhibit AP-1 activity (38), had no significant effect on Ccl2 induction (Fig. 5A). To determine which subunit of NF-κB is involved in the proinflammatory function of PKCδ, siRNA was used to silence NF-κB subunits. siRNAs against p65 and p50 efficiently and specifically knocked down p65 and p50 compared to control, respectively (Fig. 5B). Although knockdown of p65 completely eliminated the effect of PKCδ on Ccl2 mRNA (Fig. 5C), we were surprised to find that knockdown of p50 significantly increased, rather than suppressed, PKCδ-mediated Ccl2 production. Furthermore, p65 knockdown abolished the stimulatory effect of p50 knockdown on Ccl2 production (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results indicate that NF-κB subunit p65, but not p50, is critical for the up-regulation of Ccl2 by PKCδ.

FIGURE 5.

NF-κB subunit p65, but not p50, is critical for Ccl2 production by PKCδ. A, VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104 and pretreated with DMSO, andrographolide (15 μm), or SR11302 (1 μm) for 1 h before incubation with PMA (1 nm) for 6 h. Ccl2 mRNA expression was analyzed by qPCR. B, VSMCs were transfected by NF-κB subunit p50- or p65-specific siRNA, and whole-cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. C, VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104 followed by transfection of NF-κB subunit p50- or p65-specific siRNA. After 24 h, cells were treated with PMA (1 nm) for 6 h. Ccl2 mRNA expression was analyzed by qPCR. Data show the mean of independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. n = 3; *, p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

PKCδ Enhances p65 Phosphorylation and DNA Binding

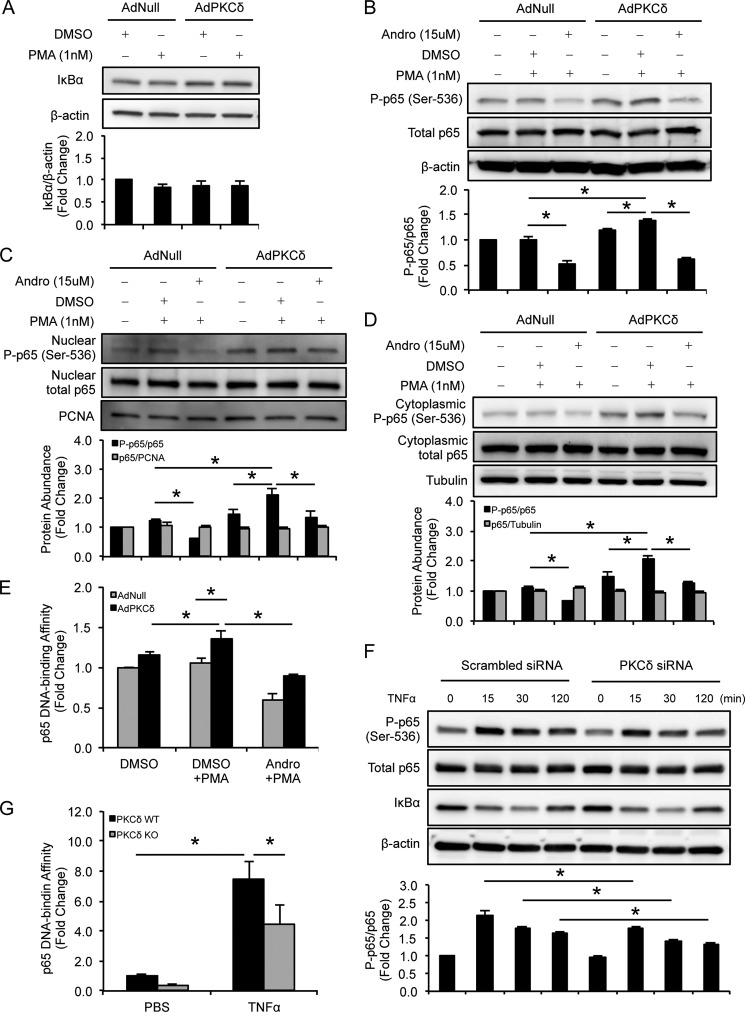

Because IκB degradation is a major signaling step leading to NF-κB activation, we examined IκBα levels in VSMCs that were infected by AdPKCδ or AdNull and then treated with or without PMA. As shown in Fig. 6A, PKCδ overexpression/activation did not produce any significant alteration of IκBα levels. We then sought to examine whether PKCδ enhances nuclear translocation of p65 by analyzing p65 protein levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. PKCδ did not cause any significant change in the ability of p65 to accumulate in the nucleus (Fig. 6, C and D).

FIGURE 6.

PKCδ enhances p65 phosphorylation and DNA binding activity. VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104 and pretreated with DMSO or andrographolide (15 μm) for 1 h before incubation with PMA (1 nm) for 2 h. Whole-cell lysates and nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies (A–D). NF-κB p65 DNA binding assays were carried out using nuclear protein (E). F, VSMCs were transfected with PKCδ-specific or scrambled siRNA for 24 h followed by incubation with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or PBS for the indicated time, and whole-cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. G, VSMCs isolated from WT and PKCδ KO mice were incubated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or PBS for 30 min. Nuclear proteins were isolated, and NF-κB p65 DNA binding assays were carried out. Data show the mean of independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. n = 3–6; *, p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA. PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; P-p65, phosphorylated p65; Andro, andrographolide.

We next examined p65 phosphorylation status, which is known to influence p65 dimerization (39), DNA binding (40), and transactivation capacity (40, 41). As shown in Fig. 6B, PKCδ overexpression/activation significantly increased p65 phosphorylation at serine 536. This induction was prohibited by andrographolide (15 μm) (Fig. 6B). Next, we examined p65 in the nuclear and cytosolic fractions and found that PKCδ overexpression/activation significantly increased p65 phosphorylation at serine 536 in both nuclear and cytosolic fractions. This induction was also found to be sensitive to andrographolide (Fig. 6, C and D). In contrast, PKCδ did not alter the phosphorylation status of p65 at Ser-276 (data not shown). Moreover, despite the unaltered nuclear accumulation of p65, the levels of p65 that bound to DNA were significantly increased by PKCδ overexpression/activation (Fig. 6E). Gene deficiency of Prkcd had no significant effect on the basal level of NF-κB subunit p65. However, the lack of PKCδ significantly attenuated the effect of TNFα on p65 including Ser-536 phosphorylation and DNA binding (Fig. 6, F and G). In addition, knockdown of PKCδ did not produce any significant alteration in protein levels of IκBα (Fig. 6F), suggesting that PKCδ activates p65 through an IκB-independent mechanism.

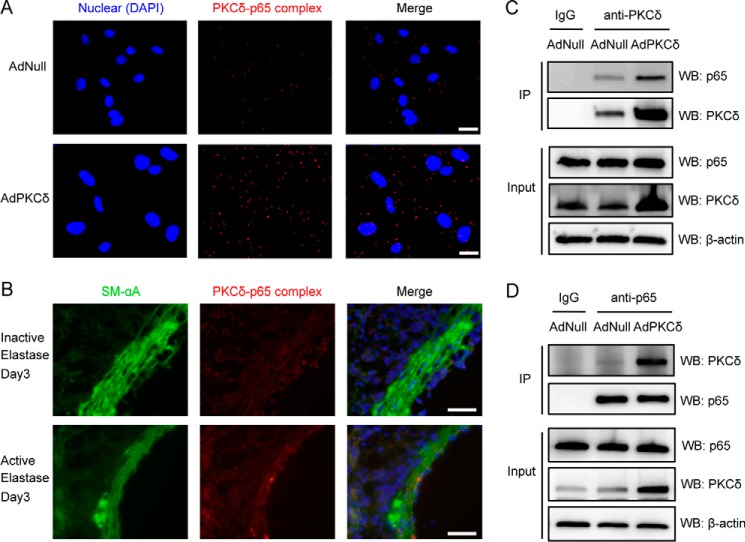

PKCδ Forms a Complex with p65 in VSMCs

Using the in situ proximity ligation assay that detects two proteins within 40 nm, we discovered that PKCδ and p65 might be physically associated with one another. The number of PKCδ-p65 complexes was found to be more abundant in PKCδ-overexpressing cells (Fig. 7A). Co-immunoprecipitation analysis showed that p65 immunoprecipitated with PKCδ, and overexpression of PKCδ by adenoviral vector increased the amount of co-immunoprecipitated p65 (Fig. 7C). In the reciprocal experiment, PKCδ co-immunoprecipitated with p65, confirming the PKCδ-p65 interaction (Fig. 7D). To detect PKCδ-p65 interaction in vivo, we used an elastase-induced model of abdominal aortic aneurysm (42). Interestingly, PKCδ-p65 complexes were visible in aortas treated with elastase or heat-inactivated elastase (control). However, the abundance of PKCδ-p65 complexes, particularly those detected in medial VSMCs (marked by positivity for smooth muscle-specific α-actin), was much more pronounced in elastase-treated or aneurysmal arteries than that detected in control arteries (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Physical interaction between PKCδ and p65 in cultured VSMCs and aneurysmal tissues. A, VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104, and PKCδ and p65 complex formation was assayed by in situ PLA after addition of PMA (1 nm) for 2 h. Scale bar, 50 μm. Magnification, 20×. B, aortas of mice were treated with elastase or inactive elastase and harvested 3 days after surgery. Cross-sections were assayed for PKCδ and p65 complex formation by in situ PLA. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Smooth muscle α-actin (SM-αA) is stained green. Red dots indicate physically interacting PKCδ-p65 complexes. Scale bar, 50 μm. Magnification, 60×. VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-PKCδ (C) or anti-p65 (D) followed by immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Normal IgG was used as a negative control. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

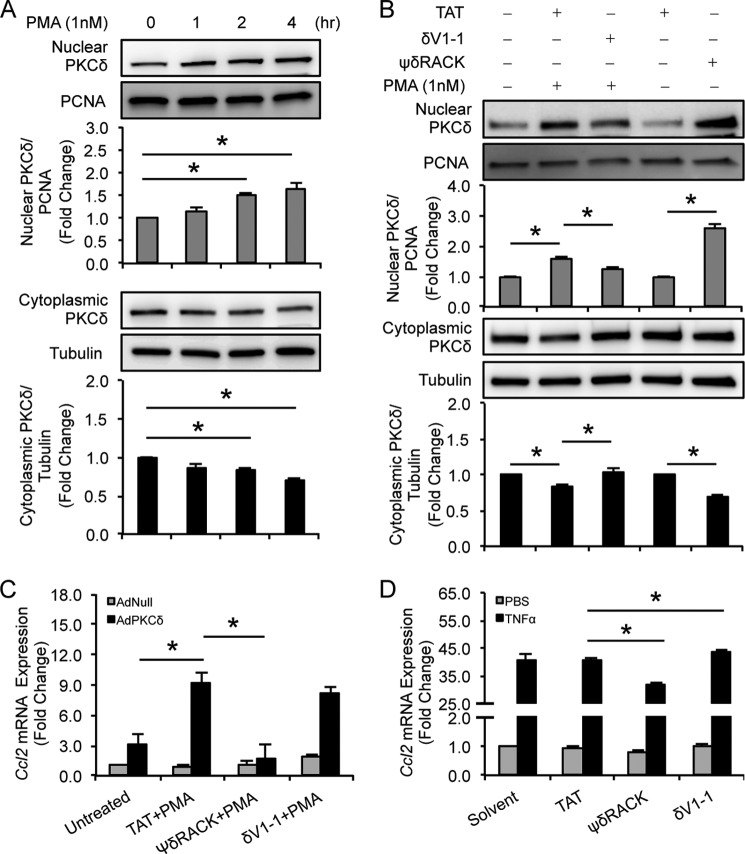

PKCδ is believed to shuttle between the cytosol and nucleus and other membrane-associated subcellular compartments. Translocation of PKCδ requires interaction of its N terminus with its specific anchoring protein called receptor for activated C-kinase (RACK) (25, 43). Subcellular analyses of PKCδ showed that the same principle applies to VSMCs with or without PKCδ overexpression. Activation of PKCδ with PMA increased nuclear accumulation of this kinase but with a slow dynamics (Fig. 8A). Because the PKCδ-p65 complexes were detected largely outside the nucleus, we postulated that manipulation of PKCδ subcellular translocation would impact PKCδ-p65 interaction and thus chemokine expression. To this end, we utilized two TAT-linked peptides developed by Mochly-Rosen and co-workers (25). Similar to what this group reported in cardiomyocytes, VSMCs responded to PKCδ-specific translocation inhibitor δV1-1 and activator ψδRACK with reduced and enhanced PKCδ nuclear translocation, respectively (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, ψδRACK nearly eliminated the ability of PKCδ to induce Ccl2 in AdPKCδ-infected VSMCs and significantly impaired Ccl2 expression in cells treated with TNFα (Fig. 8, C and D), suggesting that PKCδ nuclear translocation might impede its regulation of Ccl2 expression. Conversely, δV1-1 enhanced the Ccl2 induction in AdNull-infected VSMCs and in cells in response to TNFα (Fig. 8, C and D). However, under PKCδ-overexpressing conditions, δV1-1 did not cause an additional increase in Ccl2 expression (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Cytosolic PKCδ is critical for Ccl2 production. A, VSMCs were incubated with PMA (1 nm) for the indicated time. Cytosolic and nuclear proteins were isolated separately and subjected to immunoblot analysis. B, VSMCs were treated with PMA (1 nm for 2 h) in the absence or presence of TAT or δV1–1 (1 μm) or with TAT and ψδRACK (1 μm), respectively. Cytosolic and nuclear proteins were isolated separately and subjected to immunoblot analysis. C, VSMCs were infected with AdNull or AdPKCδ at an m.o.i. of 104 and pretreated with TAT, ψδRACK, or δV1-1 (10 μm) for 1 h before addition of PMA (1 nm) for 6 h. Ccl2 mRNA expression was analyzed by qPCR. D, VSMCs were pretreated with TAT, ψδRACK, δV1-1 (50 μm), or solvent for 1 h before addition of TNFα (10 ng/ml) or PBS for 2 h. Ccl2 mRNA expression was analyzed by qPCR. Data show the mean of independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. n = 3–6; *, p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA. PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen.

DISCUSSION

Since being cloned in 1987, PKCδ has been studied in diverse cellular processes including cell growth, apoptosis, mitogenesis, differentiation, tumor progression, and tissue remodeling (12, 44, 45). Data presented here support that PKCδ regulates vascular inflammation in part through stimulating expression of proinflammatory chemokines by VSMCs. We identified Ccl2, Ccl7, Cxcl16, and Cx3cl1 as PKCδ-regulated early response genes. All these chemokines were up-regulated in a PKCδ-dependent manner by experimental induction of abdominal aortic aneurysm, explaining at least in part the diminished inflammatory response in PKCδ-null mice we reported previously (18).

CCL2, also known as MCP-1, is a member of the small inducible gene family. Increased CCL2 expression has been reported in mechanically injured arteries (46), aortic aneurysm (47), and vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques (48). Blocking CCL2 signaling through the use of neutralizing antibodies or gene deletion of the Ccl2 gene or its receptor, Ccr2, attenuates intimal hyperplasia, aneurysm formation, and vascular inflammation in experimental models (46, 49). CCL2 is mostly known for its role in the recruitment of monocytes and other types of inflammatory cells. CCL2 can be produced by macrophages and other types of inflammatory cells. VSMCs are another important source of CCL2 when stimulated by cytokines, oxidized LDL, and bacterial lipopolysaccharide.

Prior studies including those from our own group have implicated PKCδ in the regulatory pathway of CCL2 expression (18, 19, 33). Liu et al. (50) suggested that PKCδ mediates the stability of Ccl2 mRNA when VSMCs are treated with PDGF-BB or angiotensin II. However, an early study from this group showed that TNFα has no obvious effect on Ccl2 mRNA stability (51). In our study, levels of Ccl2 mRNA declined at a similar rate regardless of the status of PKCδ expression or activity. The fact that inhibition of NF-κB by andrographolide or p65 gene silencing nearly eliminated the effect of PKCδ supports the notion that transcriptional regulation might be a predominant mode of action by elevation of PKCδ in the context of regulating chemokines.

The promoter regions of both the mouse and rat Ccl2 genes contain potential binding motifs for CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein, NF-κB, AP-1, Sp-1, and tonicity-response element/osmotic response element. Prior studies have confirmed the role of NF-κB and AP-1 as important transcription factors for Ccl2 expression (52, 53). In keeping with this notion, blocking the NF-κB pathway either with a pharmacologic inhibitor or siRNA to p65 eliminated PKCδ-mediated Ccl2 production. Although AP-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinases are known to be critical for Ccl2 expression in a wide range of cell types (52, 54, 55), inhibition of AP-1 did not significantly impact Ccl2 expression in PKCδ-overexpressing cells. This result suggests that PKCδ may not signal through the mitogen-activated protein kinase/AP-1 pathway in regulation of Ccl2; however, we cannot rule out the possibility that SR11302 at 1 μm, a common concentration reported in the literature (56), might not produce sufficient inhibition of AP-1 in VSMCs.

Another interesting and unexpected finding is the lack of involvement of the p50 NF-κB subunit. Because RelA/p65-p50 heterodimer is the major NF-κB complex detected in most cell types, one would expect that knocking down either subunit would attenuate PKCδ-induced Ccl2. Our data clearly showed that knocking down p50 significantly increased, rather than suppressed, PKCδ-mediated Ccl2 production in the absence or presence of p65 siRNA. The p50 subunit of NF-κB is synthesized as a precursor molecule of 105 kDa (p105) that functions as an inhibitor of p65. Although future studies are required to test whether the particular p50 siRNA used in the current study increases levels of p65 by reducing p105, our findings may represent the first report on differential interactions between PKCδ and NF-κB subunits.

In resting cells, NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytosol by association with IκB proteins. Upon stimulation, IκB proteins are phosphorylated, ubiquitinated, and degraded. This event constitutes a major regulatory step for NF-κB activation. Although the mechanism by which PKCδ regulates the NF-κB pathway, particularly in VSMCs, has not been well studied, studies carried out in other cell types have indicated several potential mechanisms. In neutrophils, PKCδ or its downstream effector, PKCμ, act similarly to IκB kinases by phosphorylating IκB, promoting IκB degradation, and subsequently liberating NF-κB to the nucleus (57). In endothelial cells, PKCδ is reported to increase the transactivation potential of NF-κB via an IκB kinase/IκB-independent pathway involving p38 MAPK- or Akt-mediated phosphorylation of NF-κB (58–60). In HEK293 and U2OS cells, PKCδ forms complexes with p65 in the nucleus following TNFα exposure. The PKCδ-p65 complex is believed to occupy NF-κB target gene promoters and orchestrate RelA/p65 transactivation (14). Our study revealed another mechanism that involves a cytosol-specific PKCδ-p65 interaction that is independent of the IκB pathway. In support of this novel mechanism, the PKCδ-p65 complexes were largely detected in the cytosol of VSMCs. We also observed an increased abundance of PKCδ-p65 complexes in the vascular wall of aneurysmal tissues that likely resulted from up-regulated PKCδ in diseased arteries. We do not currently know whether PKCδ activates p65 through direct or indirect phosphorylation, although this is a plausible scenario based on our observation that PKCδ enhanced phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 and increased DNA binding of this transcription factor. Numerous studies have shown that inducible post-translational modifications of NF-κB subunits, especially phosphorylation, are important for NF-κB to efficiently induce transcription of target genes (24). The p65 subunit contains 12 potential phosphoacceptor sites. Among these sites, phosphorylation at Ser-276 by protein kinase A has been thought to mediate dimerization and DNA binding of p65 (39), whereas the phosphorylation of Ser-536 increases p65 transcriptional activity (41) likely through more efficient DNA binding and recruitment of p300 (40). Furthermore, sufficient phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 is critical for NF-κB activation (40). Although NF-κB mediates most of the chemokine expression, we observed that PKCδ selectively up-regulates Ccl2, Ccl7, Cxcl16, and Cx3cl1 in VSMCs. The selective effect on gene expression might be due to site-specific phosphorylation of p65, which targets NF-κB activity to particular gene subsets by influencing p65 and phosphorylated RNA polymerase II promoter recruitment (61).

Subcellular localization is believed to be an important regulatory mechanism in determining activation and substrate specificity of the PKC family of kinases. For instance, PKCδ activates the apoptotic program through multiple inter-related events. The initiating event involves the transduction of a “death” signal to PKCδ from various apoptotic stimuli via diacylglycerol or tyrosine phosphorylation (62). Another event involves caspase-mediated cleavage, which produces the proapoptotic catalytic fragment (δCF) (12). Nuclear translocation is thought to be a final event through which PKCδ commits a cell to an apoptotic fate (62). A series of in vitro and in vivo experiments conducted by Mochly-Rosen and co-workers (25) has convincingly illustrated the importance of subcellular localization of PKCs in cardiomyocytes. They showed that a PKCδ-specific translocation inhibitory peptide (δV1-1) protects cells in ischemic hearts, whereas a translocation activator peptide (ψδRACK) increases myocyte damage after an ischemic insult (25). Using the same peptides, we confirmed their effect on PKCδ nuclear translocation in VSMCs. Surprisingly, our data suggest that nuclear translocation of PKCδ is not necessary for its action on Ccl2. In fact, the observation that ψδRACK completely disabled the ability of PKCδ to induce Ccl2 production suggests that its key substrate(s) in regulation of the Ccl2 gene is located in the cytosol. In support of this idea, our proximity ligation analysis showed that the majority of PKCδ-p65 complexes existed in the cytosol. Furthermore, blocking PKCδ translocation with δV1-1 favored Ccl2 expression. Of note, δV1-1 enhanced the Ccl2 induction in PKCδ-non-overexpressing VSMCs but did not cause additional stimulation of Ccl2 expression in PKCδ-overexpressing cells likely due to the large cytosolic presence of PKCδ under overexpression conditions. The trivial role of nuclear PKCδ in the regulation of Ccl2 gene expression is also demonstrated by our time course studies of Ccl2 mRNA induction as well as PKCδ nuclear translocation. The relatively slow dynamics of PKCδ translocation in VSMCs makes it an unlikely mechanism to be responsible for the rapid turning on of the Ccl2 gene.

It is important to point out that the PKCδ/p65 pathway is only one of several pathways involved in the regulation of proinflammatory chemokines. Aside from NF-κB (63), TNFα also utilizes AP-1 (54), Sp-1 (64), and Akt/PKB (65) pathways to regulate Ccl2. In line with this notion, altering the PKCδ pathway either through siRNA or translocation peptides caused a significant but moderate change in Ccl2 production triggered by TNFα. Despite its moderate role in the regulation of chemokine expression, mice lacking PKCδ are protected from developing vascular inflammation when subjected to aneurysm induction (18), underscoring the significance of the PKCδ pathway in the inflammatory response.

Taken together, our results suggest that PKCδ regulates CCL2 and likely other proinflammatory chemokines in VSMCs mainly at the transcriptional level. PKCδ physically interacted with the NF-κB subunit p65 in the cytosol and enhanced its DNA binding affinity likely through phosphorylation. The translocation activator peptide ψδRACK attenuated Ccl2 production, providing a way to specifically block PKCδ-regulated proinflammatory chemokines. Our evidence suggests that PKCδ has a unique role in the regulation of Ccl2 in VSMCs, and we believe these data may aid the development of drugs for future treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Daria Mochly-Rosen (Stanford University) for the generous gifts of PKCδ-specific translocation peptides used for this study.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL088447 (to B. L.).

- VSMC

- vascular smooth muscle cell

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κ-light chain enhancer of activated B cells

- CCL

- chemokine (CC motif) ligand

- MCP-1

- monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection

- qPCR

- quantitative real time PCR

- PLA

- proximity ligation assay

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- RACK

- receptor for activated C-kinase

- TAT

- transactivator of transcription.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ross R. (1999) Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. New Engl. J. Med. 340, 115–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Curci J. A., Thompson R. W. (2004) Adaptive cellular immunity in aortic aneurysms: cause, consequence, or context? J. Clin. Investig. 114, 168–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brasier A. R. (2010) The nuclear factor-κB-interleukin-6 signalling pathway mediating vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 86, 211–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lacolley P., Regnault V., Nicoletti A., Li Z., Michel J. B. (2012) The vascular smooth muscle cell in arterial pathology: a cell that can take on multiple roles. Cardiovasc. Res. 95, 194–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Libby P. (2002) Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 420, 868–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sprague A. H., Khalil R. A. (2009) Inflammatory cytokines in vascular dysfunction and vascular disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 78, 539–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kranzhöfer R., Schmidt J., Pfeiffer C. A., Hagl S., Libby P., Kübler W. (1999) Angiotensin induces inflammatory activation of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 1623–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fischer J. W. (2010) Protein kinase C δ: a master regulator of apoptosis in neointimal thickening? Cardiovasc. Res. 85, 407–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Steinberg S. F. (2004) Distinctive activation mechanisms and functions for protein kinase Cδ. Biochem. J. 384, 449–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malavez Y., Gonzalez-Mejia M. E., Doseff A. I. (2009) PRKCD (protein kinase C, δ). Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. 13, 28–42 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okhrimenko H., Lu W., Xiang C., Ju D., Blumberg P. M., Gomel R., Kazimirsky G., Brodie C. (2005) Roles of tyrosine phosphorylation and cleavage of protein kinase Cδ in its protective effect against tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23643–23652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kato K., Yamanouchi D., Esbona K., Kamiya K., Zhang F., Kent K. C., Liu B. (2009) Caspase-mediated protein kinase C-δ cleavage is necessary for apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H2253–H2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeVries T. A., Neville M. C., Reyland M. E. (2002) Nuclear import of PKCδ is required for apoptosis: identification of a novel nuclear import sequence. EMBO J. 21, 6050–6060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu Z. G., Liu H., Yamaguchi T., Miki Y., Yoshida K. (2009) Protein kinase Cδ activates RelA/p65 and nuclear factor-κB signaling in response to tumor necrosis factor-α. Cancer Res. 69, 5927–5935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kilpatrick L. E., Sun S., Mackie D., Baik F., Li H., Korchak H. M. (2006) Regulation of TNF mediated antiapoptotic signaling in human neutrophils: role of δ-PKC and ERK1/2. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80, 1512–1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Masoumi K. C., Cornmark L., Lønne G. K., Hellman U., Larsson C. (2012) Identification of a novel protein kinase Cδ-Smac complex that dissociates during paclitaxel-induced cell death. FEBS Lett. 586, 1166–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yamanouchi D., Kato K., Ryer E. J., Zhang F., Liu B. (2010) Protein kinase C δ mediates arterial injury responses through regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 85, 434–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morgan S., Yamanouchi D., Harberg C., Wang Q., Keller M., Si Y., Burlingham W., Seedial S., Lengfeld J., Liu B. (2012) Elevated protein kinase C-δ contributes to aneurysm pathogenesis through stimulation of apoptosis and inflammatory signaling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 2493–2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Si Y., Ren J., Wang P., Rateri D. L., Daugherty A., Shi X. D., Kent K. C., Liu B. (2012) Protein kinase C-δ mediates adventitial cell migration through regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in a rat angioplasty model. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 943–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richmond A. (2002) NF-κB, chemokine gene transcription and tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 664–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Israël A. (2010) The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-κB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oeckinghaus A., Ghosh S. (2009) The NF-κB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sasaki C. Y., Barberi T. J., Ghosh P., Longo D. L. (2005) Phosphorylation of RelA/p65 on serine 536 defines an IκBα-independent NF-κB pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34538–34547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Viatour P., Merville M. P., Bours V., Chariot A. (2005) Phosphorylation of NF-κB and IκB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen L., Hahn H., Wu G., Chen C. H., Liron T., Schechtman D., Cavallaro G., Banci L., Guo Y., Bolli R., Dorn G. W., 2nd, Mochly-Rosen D. (2001) Opposing cardioprotective actions and parallel hypertrophic effects of δ PKC and ϵ PKC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11114–11119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clowes A. W., Clowes M. M., Fingerle J., Reidy M. A. (1989) Kinetics of cellular proliferation after arterial injury. V. Role of acute distension in the induction of smooth muscle proliferation. Lab. Invest. 60, 360–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ryer E. J., Hom R. P., Sakakibara K., Nakayama K. I., Nakayama K., Faries P. L., Liu B., Kent K. C. (2006) PKCδ is necessary for Smad3 expression and transforming growth factor β-induced fibronectin synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 780–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang F., Tsai S., Kato K., Yamanouchi D., Wang C., Rafii S., Liu B., Kent K. C. (2009) Transforming growth factor-β promotes recruitment of bone marrow cells and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells through stimulation of MCP-1 production in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17564–17574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lengfeld J., Wang Q., Zohlman A., Salvarezza S., Morgan S., Ren J., Kato K., Rodriguez-Boulan E., Liu B. (2012) Protein kinase C δ regulates the release of collagen type I from vascular smooth muscle cells via regulation of Cdc42. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 1955–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miyamoto A., Nakayama K., Imaki H., Hirose S., Jiang Y., Abe M., Tsukiyama T., Nagahama H., Ohno S., Hatakeyama S., Nakayama K. I. (2002) Increased proliferation of B cells and auto-immunity in mice lacking protein kinase Cδ. Nature 416, 865–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoshimura K., Aoki H., Ikeda Y., Fujii K., Akiyama N., Furutani A., Hoshii Y., Tanaka N., Ricci R., Ishihara T., Esato K., Hamano K., Matsuzaki M. (2005) Regression of abdominal aortic aneurysm by inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Nat. Med. 11, 1330–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pyo R., Lee J. K., Shipley J. M., Curci J. A., Mao D., Ziporin S. J., Ennis T. L., Shapiro S. D., Senior R. M., Thompson R. W. (2000) Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Clin. Investig. 105, 1641–1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schubl S., Tsai S., Ryer E. J., Wang C., Hu J., Kent K. C., Liu B. (2009) Upregulation of protein kinase Cδ in vascular smooth muscle cells promotes inflammation in abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Surg. Res. 153, 181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ikeda U., Matsui K., Murakami Y., Shimada K. (2002) Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and coronary artery disease. Clin. Cardiol. 25, 143–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Middleton R. K., Lloyd G. M., Bown M. J., Cooper N. J., London N. J., Sayers R. D. (2007) The pro-inflammatory and chemotactic cytokine microenvironment of the abdominal aortic aneurysm wall: a protein array study. J. Vasc. Surg. 45, 574–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen H., Pan Y. X., Dudenhausen E. E., Kilberg M. S. (2004) Amino acid deprivation induces the transcription rate of the human asparagine synthetase gene through a timed program of expression and promoter binding of nutrient-responsive basic region/leucine zipper transcription factors as well as localized histone acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50829–50839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hsieh C. Y., Hsu M. J., Hsiao G., Wang Y. H., Huang C. W., Chen S. W., Jayakumar T., Chiu P. T., Chiu Y. H., Sheu J. R. (2011) Andrographolide enhances nuclear factor-κB subunit p65 Ser536 dephosphorylation through activation of protein phosphatase 2A in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 5942–5955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fanjul A., Dawson M. I., Hobbs P. D., Jong L., Cameron J. F., Harlev E., Graupner G., Lu X. P., Pfahl M. (1994) A new class of retinoids with selective inhibition of AP-1 inhibits proliferation. Nature 372, 107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhong H., Voll R. E., Ghosh S. (1998) Phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol. Cell 1, 661–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hu J., Nakano H., Sakurai H., Colburn N. H. (2004) Insufficient p65 phosphorylation at S536 specifically contributes to the lack of NF-κB activation and transformation in resistant JB6 cells. Carcinogenesis 25, 1991–2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sakurai H., Chiba H., Miyoshi H., Sugita T., Toriumi W. (1999) IκB kinases phosphorylate NF-κB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the transactivation domain. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30353–30356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Colonnello J. S., Hance K. A., Shames M. L., Wyble C. W., Ziporin S. J., Leidenfrost J. E., Ennis T. L., Upchurch G. R., Jr., Thompson R. W. (2003) Transient exposure to elastase induces mouse aortic wall smooth muscle cell production of MCP-1 and RANTES during development of experimental aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 38, 138–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mochly-Rosen D., Khaner H., Lopez J. (1991) Identification of intracellular receptor proteins for activated protein kinase C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 3997–4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim J., Koyanagi T., Mochly-Rosen D. (2011) PKCδ activation mediates angiogenesis via NADPH oxidase activity in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Prostate 71, 946–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Junttila I., Bourette R. P., Rohrschneider L. R., Silvennoinen O. (2003) M-CSF induced differentiation of myeloid precursor cells involves activation of PKC-δ and expression of Pkare. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73, 281–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roque M., Kim W. J., Gazdoin M., Malik A., Reis E. D., Fallon J. T., Badimon J. J., Charo I. F., Taubman M. B. (2002) CCR2 deficiency decreases intimal hyperplasia after arterial injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 554–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tieu B. C., Lee C., Sun H., Lejeune W., Recinos A., 3rd, Ju X., Spratt H., Guo D. C., Milewicz D., Tilton R. G., Brasier A. R. (2009) An adventitial IL-6/MCP1 amplification loop accelerates macrophage-mediated vascular inflammation leading to aortic dissection in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 119, 3637–3651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aiello R. J., Bourassa P. A., Lindsey S., Weng W., Natoli E., Rollins B. J., Milos P. M. (1999) Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 1518–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Furukawa Y., Matsumori A., Ohashi N., Shioi T., Ono K., Harada A., Matsushima K., Sasayama S. (1999) Anti-monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/monocyte chemotactic and activating factor antibody inhibits neointimal hyperplasia in injured rat carotid arteries. Circ. Res. 84, 306–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu B., Dhawan L., Blaxall B. C., Taubman M. B. (2010) Protein kinase Cδ mediates MCP-1 mRNA stabilization in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 344, 73–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu B., Poon M., Taubman M. B. (2006) PDGF-BB enhances monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA stability in smooth muscle cells by downregulating ribonuclease activity. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 41, 160–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Finzer P., Soto U., Delius H., Patzelt A., Coy J. F., Poustka A., zur Hausen H., Rösl F. (2000) Differential transcriptional regulation of the monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) gene in tumorigenic and non-tumorigenic HPV 18 positive cells: the role of the chromatin structure and AP-1 composition. Oncogene 19, 3235–3244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ueda A., Ishigatsubo Y., Okubo T., Yoshimura T. (1997) Transcriptional regulation of the human monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene. Cooperation of two NF-κB sites and NF-κB/Rel subunit specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31092–31099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Park S. K., Yang W. S., Han N. J., Lee S. K., Ahn H., Lee I. K., Park J. Y., Lee K. U., Lee J. D. (2004) Dexamethasone regulates AP-1 to repress TNF-α induced MCP-1 production in human glomerular endothelial cells. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 19, 312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Matoba K., Kawanami D., Ishizawa S., Kanazawa Y., Yokota T., Utsunomiya K. (2010) Rho-kinase mediates TNF-α-induced MCP-1 expression via p38 MAPK signaling pathway in mesangial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 402, 725–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fleenor D. L., Pang I. H., Clark A. F. (2003) Involvement of AP-1 in interleukin-1α-stimulated MMP-3 expression in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 3494–3501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vancurova I., Miskolci V., Davidson D. (2001) NF-κB activation in tumor necrosis factor α-stimulated neutrophils is mediated by protein kinase Cδ. Correlation to nuclear IκBα. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19746–19752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rahman A., Anwar K. N., Uddin S., Xu N., Ye R. D., Platanias L. C., Malik A. B. (2001) Protein kinase C-δ regulates thrombin-induced ICAM-1 gene expression in endothelial cells via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5554–5565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vanden Berghe W., Plaisance S., Boone E., De Bosscher K., Schmitz M. L., Fiers W., Haegeman G. (1998) p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways are required for nuclear factor-κB p65 transactivation mediated by tumor necrosis factor. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3285–3290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rahman A., True A. L., Anwar K. N., Ye R. D., Voyno-Yasenetskaya T. A., Malik A. B. (2002) Gαq and Gβγ regulate PAR-1 signaling of thrombin-induced NF-κB activation and ICAM-1 transcription in endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 91, 398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hochrainer K., Racchumi G., Anrather J. (2013) Site-specific phosphorylation of the p65 protein subunit mediates selective gene expression by differential NF-κB and RNA polymerase II promoter recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 285–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Reyland M. E. (2007) Protein kinase Cδ and apoptosis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 1001–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ping D., Boekhoudt G. H., Rogers E. M., Boss J. M. (1999) Nuclear factor-κB p65 mediates the assembly and activation of the TNF-responsive element of the murine monocyte chemoattractant-1 gene. J. Immunol. 162, 727–734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Boekhoudt G. H., Guo Z., Beresford G. W., Boss J. M. (2003) Communication between NF-κB and Sp1 controls histone acetylation within the proximal promoter of the monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 gene. J. Immunol. 170, 4139–4147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Murao K., Ohyama T., Imachi H., Ishida T., Cao W. M., Namihira H., Sato M., Wong N. C., Takahara J. (2000) TNF-α stimulation of MCP-1 expression is mediated by the Akt/PKB signal transduction pathway in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 276, 791–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]