Antibiotic therapy places intense selection pressure on bacteria that inevitably leads to the emergence of resistance,1 and thus the need to continually identify and develop new antibiotics. Secondary metabolite natural products have been, and seem likely to continue to be, the best source of antibacterial agents, providing the vast majority of therapeutics actually used in the clinic.2 As a result, it is of great interest to examine newly identified secondary metabolites for their potential antibacterial activity. There is a growing appreciation that plants provide a unique source of diverse secondary metabolites with potentially important biological activities, with one of the most promising classes being the indole alkaloids.3 One such indole alkaloid natural product is psychotrimine (1, Figure 1), which was isolated in 2004 from leaves of the South American shrub Psychotria rostrata,4 and has attracted considerable interest from the synthetic and medicinal chemistry communities owing to its unusual connectivity between tryptamine subunits. The peculiar N1-C3 linkage differs from the carbon-carbon linkages that are more typical of other polymeric indole alkaloids.5 Preliminary biological studies showed that psychotrimine has only mild anti-proliferative activity against several colon and lung cancer cell lines.6 While interest in the indole alkaloids has generally been focused on their anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and neurological activities, there is growing evidence that these compounds may provide promising scaffolds for antibiotic development.3

Figure 1.

Structure of psychotrimine (1) and derivatives 2 and 3.

With access to psychotrimine provided by the recently reported gram scale total synthesis,6 we sought to examine the potential antibacterial activity of this unique indole alkaloid. We first screened a variety of bacteria for sensitivity to psychotrimine according to CLSI guidelines.7 No activity was observed against P. aeruginosa PA01 or K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 up to 128 µg ml−1. We observed mild activity against E. coli MG1655, inhibiting growth with a minimum inhibitor concentration (MIC) of 128 µg ml−1. Polymyxin B nonapeptide does not sensitize E. coli to psychotrimine, suggesting that the absence of activity against Gram-negative bacteria is not the result of limited outer membrane penetration. In contrast, more significant activity against Gram-positive bacteria was observed. Psychotrimine is reasonably active against B. subtilis 168, S. agalactiae COH1, and S. pyogenes 5448, inhibiting growth of each with an MIC of 16 µg ml−1, and moderately active against S. epidermidis RP62A and S. aureus 8325, inhibiting growth with an MIC of 32 µg ml−1 and 64 µg ml−1, respectively.

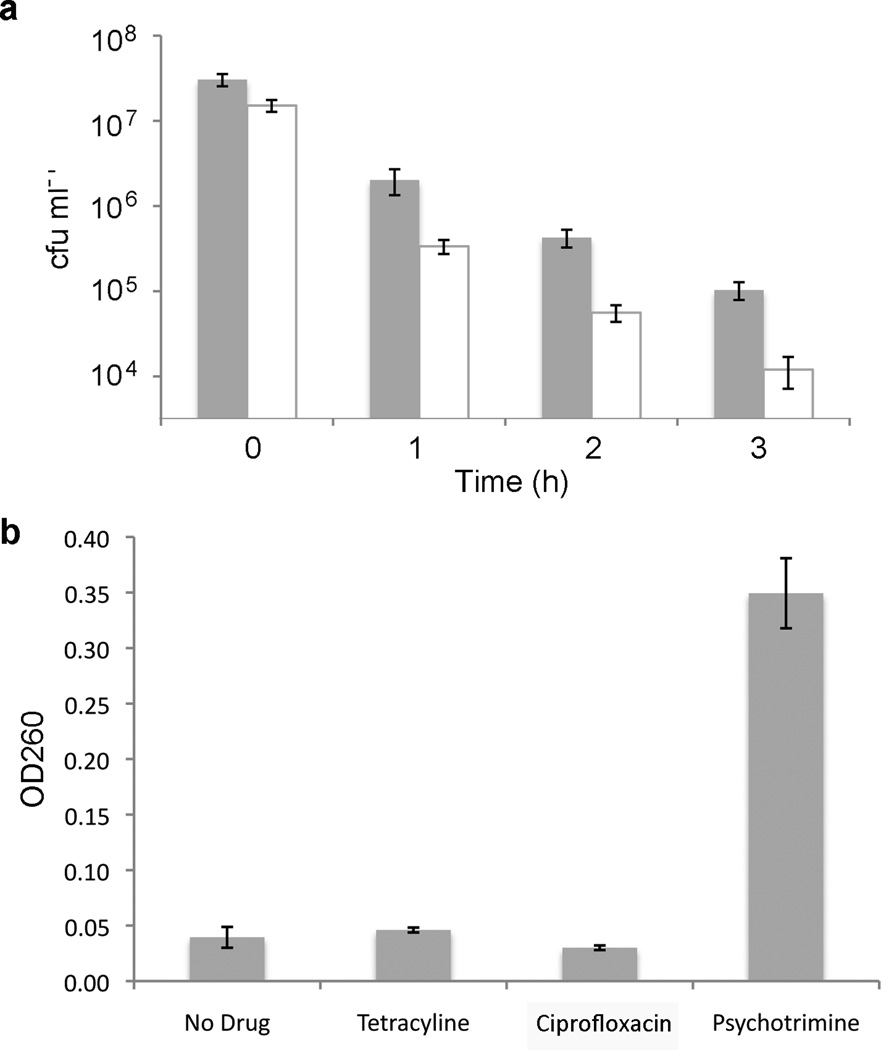

To further understand the Gram-positive activity of psychotrimine, we constructed kill curves for both S. aureus and B. subtilis. Log phase bacteria (1 × 107 cfu) were inoculated into Mueller-Hinton media containing 2× MIC of psychotrimine and incubated with shaking at 37 °C. Aliquots were removed at various time points and appropriate dilutions were plated onto Mueller-Hinton agar to determine the number of viable cells. After only three hours, we observed a 300- and 1,300-fold decrease in viable cells for S. aureus and B. subtilis, respectively, indicating that psychotrimine has bactericidal activity (Figure 2a). Moreover, exposure of S. aureus to psychotrimine for only 40 minutes reduced the viable cell count 90% and reduced the OD590 of the culture 25%, indicating bacteriolytic activity.

Figure 2.

(a) Viable cell count following psychotrimine treatment of S. aureus (filled) and B. subtilis (open); and (b) absorption at 260 nm of supernatant from S. aureus cells following antibiotic treatment in phosphate buffered saline (normalized for absorption of the antibiotic). Error bars represent standard deviation of at least three independent experiments.

To begin to understand the mechanism by which psychotrimine kills Gram-positive bacteria, we attempted to isolate resistant mutants of B. subtilis and S. aureus. However, after plating >5 × 109 cfu on Mueller-Hinton agar plates containing 2× MIC psychotrimine, no viable colonies could be recovered. Moreover, serial passage of B. subtilis cells in sub-MIC concentrations of psychotrimine for fifty generations also failed to yield resistant colonies. This data suggests that resistant mutants, at least in B. subtilis and S. aureus, are extremely rare. Such low levels of resistance are common with a variety of mechanisms, including membrane disruption, which is also consistent with the positively charged lipophilic structure of psychotrimine.8

Most antibiotics that act via membrane disruption show synergistic activity when combined with other antibiotics that are limited by membrane penetration because they increase access to intracellular targets.9 Accordingly, we determined the MICs of rifampin and erythromycin against E. coli and S. aureus as a function of psychotrimine concentration. Rifampin and erythromycin are limited by membrane penetration with E. coli but not with S. aureus.10 Psychotrimine showed substantial synergy with rifampin and erythromycin against E. coli, with 32 µg ml−1 (0.25× MIC) sensitizing E. coli cells 16-fold and 8-fold, respectively. In contrast, psychotrimine showed no interaction at any concentration with either drug against S. aureus. The observed synergy between rifampin or erythromycin and psychotrimine with E. coli but not S. aureus is further evidence for a membrane disruption-based mechanism of action.

We next employed a more direct assay for psychotrimine-mediated membrane disruption, which relies upon the detection of intracellular material released into the media following antibiotic treatment in osmotically-stabilized buffer (Figure 2b).11 This assay was recently reported by O’Neill and coworkers to be more reliable than other assays used to detect membrane damage in S. aureus.12 S. aureus cells were grown to saturation and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline to remove any extracellular material. The cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer containing 1× MIC of psychotrimine, tetracycline, or ciprofloxacin. After 30 minutes of shaking at room temperature, the cells were removed by filtration and the OD260 of the supernatants was determined. As a control, a sample without any antibiotic was also prepared to account for any residual cell lysis and/or protein secretion. The OD260 of the tetracycline- and ciprofloxacin-treated samples was 0.046 ± 0.002 and 0.030 ± 0.002, respectively, which are within error of that for the non-treated control (0.039 ± 0.009), consistent with little or no disruption of the bacterial membrane.12 In contrast, the OD260 of the supernatant from the psychotrimine-treated sample was 0.349 ± 0.032. This value is comparable to those previously reported for agents that strongly disrupt membranes, such as detergents and the natural product nisin.12 Because under the conditions employed there is little to no cell growth, it is unlikely that any cell lysis results from the inhibition of cellular targets. Thus, we conclude that psychotrimine acts by disrupting the cytoplasmic membrane of Gram-positive bacteria.

Two analogs (Figure 1) were synthesized to address whether the lipophilicity and positive charge of psychotrimine contribute to its antibacterial activity, as observed with other agents known to disrupt membranes.8 The C7-linked tryptamine unit of psychotrimine is removed in compound 2 and both secondary methylamines are acylated in compound 3. In both cases, at least one positive charge is removed. Information on the synthesis and characterization of the compounds is given in Supplementary Information. Both compounds 2 and 3 were found to have lost all activity against all of the bacteria tested (MIC > 128 µg ml−1). This data suggests that the presence of both secondary amines is critical for psychotrimine activity and is further consistent with a mechanism of action based on membrane disruption.

In conclusion, we have shown psychotrimine disrupts the cytoplasmic membranes of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and that in the latter case this results in reasonably potent antibacterial activity. The specific Gram-positive activity likely arises from unique aspects of their cytoplasmic membrane, such as charge or lipid composition, and similar activities have been observed with other plant indole alkaloids with structural homology to psychotrimine.13,14 This class of antimicrobials may be an important component of the plant defense system against the bacterial and perhaps fungal pathogens common in their environment. Due to the producing plants protective cell wall, these molecules can be produced at the high levels required for activity and their mechanism of action makes them less susceptible to the evolution of resistance than are more potent but target specific antibiotics.15 Importantly, the biological insights generated in this study were only made possible from the large quantity of psychotrimine and its derivatives generated via total synthesis. Modifications of the synthesis should make possible similar analyses of other complex polymeric indole alkaloids and the further exploration of the potential biological activities of these interesting and novel secondary metabolites.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI081126 to F.E.R and CA134785 to P.S.B.)

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at The Journal of Antibiotics website.

References

- 1.Clardy J, Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. New antibiotics from bacterial natural products. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1541–1550. doi: 10.1038/nbt1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler MS, Buss AD. Natural products--the future scaffolds for novel antibiotics? Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;71:919–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gul W, Hamann MT. Indole alkaloid marine natural products: an established source of cancer drug leads with considerable promise for the control of parasitic, neurological and other diseases. Life Sci. 2005;78:442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takayama H, Mori I, Kitajima M, Aimi N, Lajis NH. New type of trimeric and pentameric indole alkaloids from Psychotria rostrata. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2945–2948. doi: 10.1021/ol048971x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newhouse T, Baran PS. Total synthesis of (+/−)-psychotrimine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10886–10887. doi: 10.1021/ja8042307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newhouse T, Lewis CA, Eastman KJ, Baran PS. Scalable total syntheses of N-linked tryptamine dimers by direct indole-aniline coupling: psychotrimine and kapakahines B and F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7119–7137. doi: 10.1021/ja1009458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ, Pompliano DL. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol. Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaara M, Vaara T. Sensitization of Gram-negative bacteria to antibiotics and complement by a nontoxic oligopeptide. Nature. 1983;303:526–528. doi: 10.1038/303526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson CF, Mee BJ, Riley TV. Mechanism of action of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil on Staphylococcus aureus determined by time-kill, lysis, leakage, and salt tolerance assays and electron microscopy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1914–1920. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1914-1920.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Neill AJ, Miller K, Oliva B, Chopra I. Comparison of assays for detection of agents causing membrane damage in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;54:1127–1129. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbons S. Anti-staphylococcal plant natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004;21:263–277. doi: 10.1039/b212695h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmud Z, Musa M, Ismail N, Lajis NH. Cytotoxic and bacteriocidal activities of Psychotria rostrata. Int. J. Pharmacog. 1993;31:142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis K, Ausubel FM. Prospects for plant-derived antibacterials. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1504–1507. doi: 10.1038/nbt1206-1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.