Summary

After implementation of an integrated consulting psychiatry model and psychology services within primary care at a federally qualified health center, patients have increased access to needed mental health services, and primary care clinicians receive the support and collaboration needed to meet the psychiatric needs of the population.

Keywords: Access to care, primary care, community health centers, medically underserved, psychiatry, behavioral medicine

Primary care is frequently referred to as the de facto mental health system in the United States.1, 2 Primary care clinicians are facing the burden of an ever-increasing number of patients presenting with major mental illness.3 Under a treatment model whereby clinics must refer patients elsewhere for mental health treatment, less than one-third of these referrals are actually completed.3 Negative beliefs associated with mental health care,4 including stigma coinciding with receiving mental health treatment,5, 6 are proven patient barriers to seeking appropriate mental health care. Other potential barriers to attending off-site referrals include lack and cost of transportation, distance from service providers, limited clinic hours, and lack of available appointments or insurance coverage.7–10 Thus, primary care clinicians are taking on more prescribing authority for patients with complex mental health issues. In the United States, a majority of patients with mental health concerns receive treatment within primary care.2, 11, 12

Given the volume of patients who receive their psychiatric care within the primary care system and experience issues with poor follow-up when referral occurs outside the clinic, increased access to consulting psychiatry is needed to provide optimal management of an increasing number of patients with a mental illness within primary care. The need to integrate psychiatry and other mental health providers into the primary care team is heightened particularly for subpopulations with structural barriers that restrict access to care.13 Providing mental health services within the primary care setting also affords patients the option of receiving the care they need in an environment that they find familiar and acceptable.14 Differing models of incorporating the use of psychiatry in the primary care environment exist with the psychiatrist functioning in various capacities.11, 15–18 However, the literature lacks robust, practical descriptions of the development and implementation of an integrated psychiatric consultation model in primary care with the psychiatrist routinely working in collaboration with both primary care clinicians and other mental health providers.

In this article, we describe our integrated model of team collaboration between psychiatrists, behavioral health consultants (other mental health providers), and primary care clinicians. Specifically, we describe how this model uses a population-based framework to provide efficient, whole-person care.

Description of Patient and Provider Population

Access Community Health Centers (ACHC) constitute a federally qualified health center (FQHC) with three locations in Madison, Wisconsin. These clinics provide dental, medical, and behavioral health care services to patients regardless of ability to pay. All types of insurance are accepted and there is also a sliding fee scale for uninsured or underinsured patients. In 2012, there were 110,621 clinical encounters with patients. Characteristics of the patient population in 2012 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

ACHC Patient Characteristics in 2012 (N=25,062)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, in years | ||

| 0–19 | 8,787 | 35 |

| 20–64 | 14,860 | 59 |

| 65+ | 1,415 | 6 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 10,467 | 42 |

| Female | 14,595 | 58 |

| Health insurance type | ||

| Uninsured | 9,078 | 36 |

| Medicaid | 12,003 | 48 |

| Private/commercial | 2,945 | 12 |

| Medicare | 1,036 | 4 |

| Race | ||

| Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1,208 | 5 |

| Black/African American | 5,396 | 22 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1,818 | 7 |

| White | 11,946 | 48 |

| Unreported/refused to report | 4,694 | 19 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 6,669 | 27 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 17,118 | 68 |

| Unreported/refused to report | 1,275 | 5 |

| Primary language spoken | ||

| English | 19,370 | 77 |

| Other | 5,692 | 23 |

ACHC = Access Community Health Center

Percentages may not total to 100 due to rounding

Primary care clinicians and behavioral health consultants work together in a fully integratedand fully embedded model focused on population-based care. Primary care clinicians at the clinics include family medicine physicians, internal medicine physicians, pediatricians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. The behavioral health consultation team consists of psychologists, social workers, and trainees (e.g., practicum students, interns, and post-doctoral fellows). Patient appointments with behavioral health consultants are usually 15–30 minutes, mimicking the primary care pace and style of intervention. Primary care clinicians refer patients to the behavioral health consultant, who is available for both scheduled and same-day appointments. The goal of this consultation is to assess day-to-day functioning, potential severity of impairment from symptoms, and opportunities for brief interventions for patients.19

Development of the Psychiatric Consultation Service

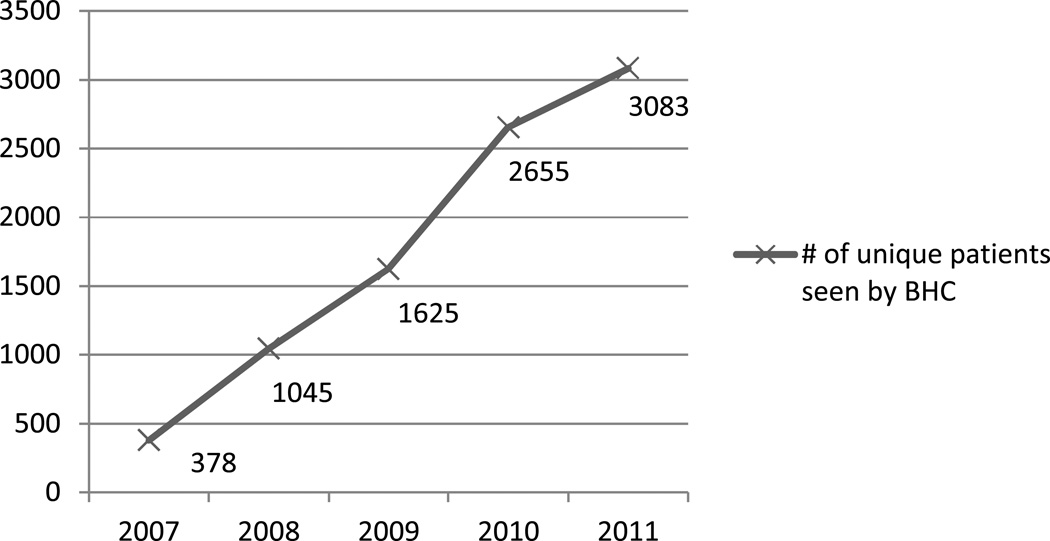

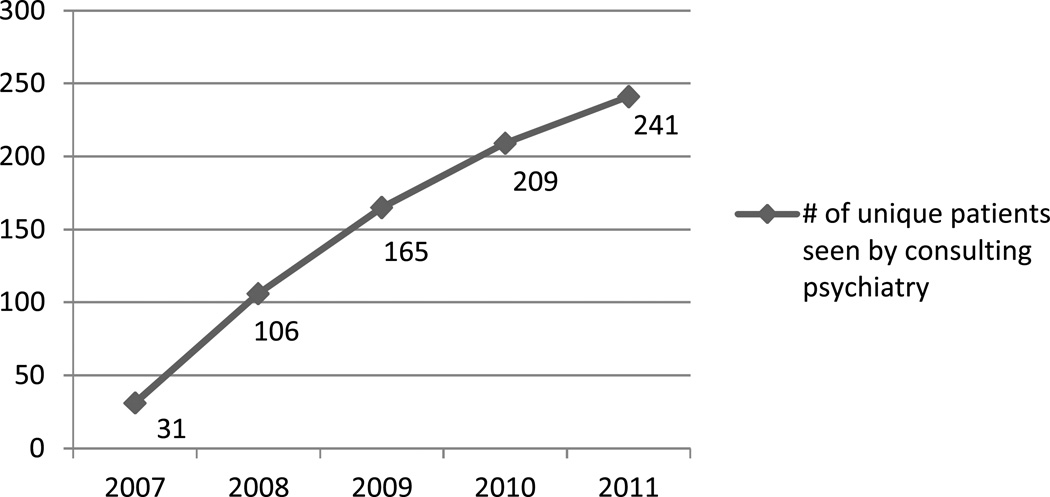

The psychiatric consultation service began in 2007 with the goal of developing an integrated model in which the psychiatrist provides consultation services with a population-based care focus, similar to the behavioral health consultation model. Developing the service first involved a clinic needs assessment to determine how this logistically would fit best in the environment. Additional requirements for a successful psychiatric consultation service have included additional work space (including an examination room to see patients) and a psychiatrist who was willing and able to thrive in the fast-paced, challenging primary care environment. The following personal attributes were considered to be important for this consulting psychiatrist: flexibility/adaptability, confidence, ability to function as part of a team, understanding of the context of the FQHC setting (including limited patient resources), a population-based care focus, a broad range of training experiences, and knowledge of non-pharmacologically-based interventions. Figures 1 and 2 show the growth in utilization of the behavioral health consultant and consulting psychiatry services from 2007 to 2011.

Figure 1.

Number of unique patients seen by BHC

BHC = Behavioral Health Consultant

Figure 2.

Number of unique patients seen by consulting psychiatry

Role of the Psychiatric Consultation Service

Clarification of provider roles (consulting psychiatrist, primary care clinician, behavioral health consultant) is an essential part of the discussion with patients at the outset of any contact involving the consulting psychiatrist. The consulting psychiatrist provides an opinion about diagnosis or differential diagnosis, recommendations about further diagnostic testing that may be helpful, and management options (including providing several medication options when medications are deemed appropriate) that account for the possibility of failed medication trials. However, it is the primary care clinician who provides ongoing care with support from the behavioral health consultation team. The primary care clinician always maintains prescriptive authority, including choosing the strategy for medication implementation based on recommendations outlined in the consult note. Care is coordinated via conversation among the consulting psychiatrist, behavioral health consultant, and primary care clinician; given the fast pace of the primary care environment, communication via electronic health record (EHR) is also frequently utilized.

Psychiatric consultation within primary care can occur through multiple modalities ranging from face-to-face clinical patient interviews, case consultation through conversation, and/or chart reviews. Consultation is differentiated from traditional outpatient psychiatric care as there is no ongoing treatment or management by the psychiatrist. The results of the consultation can generate diagnostic clarification, targeted medication algorithms complete with dosing and necessary laboratory/medical monitoring, general psychotropic education covering the most common and important side effects, and other behavioral and community referral recommendations.

The behavioral health consultant serves as a conduit for facilitating access to the psychiatrist. He or she sees patients prior to being scheduled with consulting psychiatry to determine appropriateness of referral, current target symptoms, history, and severity. This individual then submits a consultation request via the EHR documenting the reason for the consult and a brief overview of target symptoms. There is a lead behavioral health consultant who manages all requests for consultation and triages needs according to severity.

The behavioral health consultants also lead brief multidisciplinary team meetings at the beginning of each clinic day when the consulting psychiatrist is present. The purpose is to review the current schedule for the day, including rationale for consults, specific consultation questions, and patients’ insurance status so that the psychiatrist is able to make feasible medication recommendations.

The psychiatrist seeing a patient in a primary care office has the advantage of having electronic access to all the patient’s current medications, medical conditions, laboratory data, and vital signs. This information can be difficult to obtain in the traditional outpatient psychiatric practice due to physical lags in faxing information, phone calls, proper releases being filed, and mail and copy time. The consulting psychiatrist in primary care has a more accurate medical picture of each patient, including comorbid medical problems that may exacerbate psychiatric conditions. Psychotropic medications that can treat active medical conditions and the presenting psychiatric condition can be prioritized while overlapping prescriptions for psychotropic medications can be avoided. This integration can decrease the risk of a patient abusing medications such as stimulants, benzodiazepines, or other hypnotics. Potential medication interactions can be reviewed more accurately and potential additive side effects can be anticipated or avoided.

Training the Primary Care Consulting Psychiatrists of the Future

Due to the growth in primary care-centered health care and the emergence of the patient-centered medical home, it is crucial that future psychiatrists receive training on how to function as team members within this setting. Psychiatry residents will need to be adequately trained to work within an integrated health care home and be able to collaborate effectively with primary care clinicians and other disciplines.

Starting in 2010, ACHC has collaborated with the University of Wisconsin’s Department of Psychiatry to develop a residency training opportunity in community psychiatry that consists of a three-month rotation. All residents are supervised on site by the consulting psychiatrist. The main goals of this collaboration are to teach residents to function as members of a multidisciplinary team within an integrated model that is focused on reaching the needs of a population, while being mindful of socio-economic status and psychosocial barriers. In addition, we hope it will inspire future psychiatrists to practice within primary care medical homes, and in particular, FQHC settings. Residents learn to adapt to the pace and culture of primary care, develop consultation skills, assess and diagnose psychiatric and behavioral issues common in primary care settings, make detailed recommendations regarding pharmacological interventions, communicate clearly and efficiently with primary care providers, participate in case consultations and training seminars for primary care clinicians, and have broadened exposure to more severe and persistent mental illness in the context of complex medical issues and limited resources.

Conclusions

The literature documents numerous benefits of incorporating mental health services within primary care including decreased healthcare costs,20 increased identification of mental health issues,21, 22 increased accessibility to mental health services,23–25 improved patient outcomes,26–31 and patient and provider satisfaction.32 However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated the effectiveness of routine collaboration between consulting psychiatrists, behavioral health consultants, and primary care clinicians. There is a need for formal research in this area.

Overall, the integration of a consulting psychiatry service within our behavioral health consultation service has been an enormous asset to both patients and providers at ACHC. The consulting psychiatry program is an example of how to extend the utility of a psychiatric resource to maximize benefit to a population. Many psychiatrically complex patients can be successfully managed within a primary care environment with assistance from behavioral health consultants and access to consulting psychiatry, as illustrated in a recent study of depression care processes at ACHC.33 In addition, having a psychiatric consultant and behavioral health consultation team on-site can assist primary care clinicians with following evidenced-based treatment guidelines involving both pharmacological and behavioral interventions. One of the intended non-specific benefits of the consulting psychiatry program is the increased competency and independence of primary care clinicians in prescribing and managing patients with mental illness. With each exposure to recommendations from and interaction with the consulting psychiatrist, primary care clinicians may improve their knowledge base and skills in mental health care. Additionally, positioning the psychiatrist’s work space alongside that of the primary care clinicians has increased collaboration, ongoing psycho-education, and reciprocal learning. Exposing psychiatry residents to this model of care can prepare future psychiatrists to work within an integrated primary care environment. A free toolkit showing the workflow between our primary care clinicians, behavioral health consultants and consulting psychiatrists is available online at www.hipxchange.org.

Acknowledgments

Nancy Pandhi is supported by a National Institute on Aging Mentored Clinical Scientist Research Career Development Award, grant number l K08 AG029527. The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 9U54TR000021. Additional support was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program. The authors thank Lauren Fahey and Zaher Karp for their assistance in manuscript formatting.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented at the Collaborative Family Healthcare Association (CFHA) 13th Annual Conference October 29, 2011 in Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Cummings NA, O'Donohue W, Hays SC, et al. Integrated Behavioral Healthcare: Positioning Mental Health Practice with Medical/Surgical Practice. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA. The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978 Jun;35(6):685–693. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300027002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mechanic D, Bilder S. Treatment of people with mental illness: a decade-long perspective. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 Jul-Aug;23(4):84–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, et al. Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2009 Aug;60(8):1118–1122. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim PY, Thomas JL, Wilk JE, et al. Stigma, Barriers to Care, and Use of Mental Health Services Among Active Duty and National Guard Soldiers After Combat. Psychiatric Services. 2010 Jun;61(6):582–588. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pailler ME, Cronholm PF, Barg FK, et al. Patients' and caregivers' beliefs about depression screening and referral in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009 Nov;25(11):721–727. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181bec8f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldner EM, Jones W, Fang ML. Access to and waiting time for psychiatrist services in a Canadian urban area: a study in real time. Can J Psychiatry. 2011 Aug;56(8):474–480. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruzich JM, Jivanjee P, Robinson A, et al. Family caregivers' perceptions of barriers to and supports of participation in their children's out-of-home treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2003 Nov;54(11):1513–1518. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mechanic D. Removing barriers to care among persons with psychiatric symptoms. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002 May-Jun;21(3):137–147. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pieh-Holder KL, Callahan C, Young P. Qualitative needs assessment: healthcare experiences of underserved populations in Montgomery County, Virginia, USA. Rural Remote Health. 2012 Jul;12(3):1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirl WF, Beck BJ, Safren SA, et al. A Descriptive Study of Psychiatric Consultations in a Community Primary Care Center. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 Oct;3(5):190–194. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v03n0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norquist GS, Regier DA. The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders and the de facto mental health care system. Annual Review of Medicine. 1996;47:473–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham P, McKenzie K, Taylor EF. The struggle to provide community-based care to low-income people with serious mental illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006 May-Jun;25(3):694–705. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang AJ. Mental health treatment preferences of primary care patients. J Behav Med. 2005 Dec;28(6):581–586. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowley DS, Katon W, Veith RC. Training psychiatry residents as consultants in primary care settings. Acad Psychiatr. 2000 Fal;24(3):124–132. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kates N, Craven M, Crustolo AM, et al. Integrating mental health services within primary care. A Canadian program. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1997 Sep;19(5):324–332. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(97)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nickels MW, McIntyre JS. A model for psychiatric services in primary care settings. Psychiatric Services. 1996 May;47(5):522–526. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.5.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Van Os TW, Van Marwijk HW, et al. Effect of psychiatric consultation models in primary care. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Psychosom Res. 2010 Jun;68(6):521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson PJ, Reiter JT. Behavioral Consultation and Primary Care. NY: Springer Science; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katon WJ, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, et al. Cost-effectiveness and cost offset of a collaborative care intervention for primary care patients with panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002 Dec;59(12):1098–1104. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodlund O, Andersson SO, Mallon L. Effects of consulting psychiatrist in primary care. 1-year follow-up of diagnosing and treating anxiety and depression. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1999 Sep;17(3):153–157. doi: 10.1080/028134399750002566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kates N, Craven M, Crustolo AM, et al. Mental health services in the family physician's office: a Canadian experiment. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1998;35(2):104–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biderman A, Yeheskel A, Tandeter H, et al. Advantages of the psychiatric liaison-attachment scheme in a family medicine clinic. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1999;36(2):115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kates N, McPherson-Doe C, George L. Integrating mental health services within primary care settings: the Hamilton Family Health Team. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011 Apr-Jun;34(2):174–182. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31820f6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weingarten M, Granek M. Psychiatric liaison with a primary care clinic--14 years' experience. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1998;35(2):81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryan CJ, Morrow C, Appolonio KK. Impact of behavioral health consultant interventions on patient symptoms and functioning in an integrated family medicine clinic. J Clin Psychol. 2009 Mar;65(3):281–293. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ. 2006 Feb 4;332(7536):259–263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999 Dec;56(12):1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995 Apr 5;273(13):1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Oct;61(10):1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Pearson SD, et al. Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Arch Fam Med. 2000 Apr;9(4):345–351. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isomura T, Senay J, Haldin C, et al. Bridging with primary care: A shared-care mental health pilot project. BC Medical Journal. 2002;44(8):412–414. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serrano N, Monden K. The effect of behavioral health consultation on the care of depression by primary care clinicians. WMJ. 2011 Jun;110(3):113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]