Abstract

Aims

Prior studies evaluating the prognostic utility of cardiac CT angiography (CCTA) have been largely constrained to an all-cause mortality endpoint, with other cardiac endpoints generally not reported. To this end, we sought to determine the relationship of extent and severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) by CCTA to risk of incident major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) (defined as death, myocardial infarction, and late revascularization).

Methods and results

We identified subjects without prior known CAD who underwent CCTA and were followed for MACE. CAD by CCTA was defined as none (0% luminal stenosis), mild (1–49% luminal stenosis), moderate (50–69% luminal stenosis), or severe (≥70% luminal stenosis), and ≥50% luminal stenosis was considered as obstructive. CAD severity was judged on per-patient, per-vessel, and per-segment basis. Time to MACE was estimated using univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. Among 15 187 patients (57 ± 12 years, 55% male), 595 MACE events (3.9%) occurred at a 2.4 ± 1.2 year follow-up. In multivariable analyses, an increased risk of MACE was observed for both non-obstructive [hazard ratio (HR) 2.43, P < 0.001] and obstructive CAD (HR: 11.21, P < 0.001) when compared with patients with normal CCTA. Risk-adjusted MACE increased in a dose–response relationship based on the number of vessels with obstructive CAD ≥50%, with increasing hazards observed for non-obstructive (HR: 2.54, P < 0.001), obstructive one-vessel (HR: 9.15, P < 0.001), two-vessel (HR: 15.00, P < 0.001), or three-vessel or left main (HR: 24.53, P < 0.001) CAD.

Among patients stratified by age <65 vs. ≥65 years, older individuals experienced higher risk-adjusted hazards for MACE for non-obstructive, one-, and two-vessel, with similar event rates for three-vessel or left main (P < 0.001 for all) compared with normal individuals age <65. Finally, there was a dose relationship of CAD findings by CCTA and MACE event rates with each advancing decade of life.

Conclusion

Among individuals without known CAD, non-obstructive, and obstructive CAD are associated with higher MACE rates, with different risk profiles based on age.

Keywords: Age, Major adverse cardiac events, Coronary artery disease, Prognosis, coronary CT angiography

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1,2 The severity and prevalence of CAD increases with age,3 with patients older than 75 years more likely having multi-vessel CAD.4 However, the presence of CAD in young patients is not benign and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.5 Invasive coronary angiography (ICA) has traditionally been used as an anatomic standard for the diagnosis and prognosis of CAD. Coronary CT angiography (CCTA) of 64-detector rows or greater has emerged as a non-invasive modality that demonstrates high diagnostic performance compared with ICA.6,7 While CAD findings by CCTA have been examined for their prognostic utility in several prior investigations, published studies to date have been generally restricted to single centres and limited to measures of obstructive CAD and all-cause mortality endpoints.8–11 Further, given smaller sample sizes, these studies were constrained to evaluating cohorts in entirety and thus, were not able to discern differences in risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACEs), particularly based on differences in age.5,12 To this end, we sought to determine in a prospective international multisite registry of 15 187 patients the relationship of the extent and severity of CAD by CCTA to risk of incident MACEs and further, to examine this relationship as a function of age.

Methods

Study population

Study patients were identified from the CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter) registry, a dynamic, international, multicentre, observational cohort study that prospectively collects clinical, procedural, and follow-up data on patients who underwent ≥64-detector row CCTA between 2005 and 2009 at 12 centres in 6 countries (Canada, Germany, Italy, Korea, Switzerland, and the USA). The rationale, design, site-specific patient characteristics, and follow-up durations have been described previously.13 Patients undergoing CCTA at eight centres for whom the MACE follow-up were screened for the present study analysis, while those individuals with known CAD, as defined by prior myocardial infarction (MI) or coronary revascularization, or cardiac transplantations were excluded.

CCTA protocol and image reconstruction

CCTA scans were performed on a variety of different scanner platforms as previously described.14 The scan parameters were as follows: 64 × 0.625/0.750-mm collimation, tube voltage 100 or 120 mV, effective 400–650 mA. Dose reduction strategies were utilized as previously described,14 and the phase with the least amount of coronary artery motion was chosen for analysis. CCTAs were evaluated by an array of post-processing imaging techniques, and every arterial segment was scored in an intent-to-diagnose fashion.

Non-invasive coronary artery assessment by CCTA

The visual interpretation of CCTA at all the study sites was performed by level III equivalent cardiologist and all coronary segments were scored using a 16-segment coronary artery model. Coronary atherosclerotic lesions were graded by visual estimation using a 4-point grading system: none (0% luminal stenosis), mild (1–49% luminal stenosis), moderate (50–69% luminal stenosis), or severe (≥70% luminal stenosis). Per cent obstruction of the coronary artery lumen was based on a comparison of the luminal diameter of the segment exhibiting obstruction to the luminal diameter of the most normal-appearing site immediately proximal to the plaque.

Plaque severity was graded on a per-patient, per-vessel, and per-segment basis. Per-patient severity was defined by the maximal stenosis in any coronary segment at the ≥50% stenosis threshold, with a ≥50% stenosis left main considered obstructive. Per-vessel CAD severity was defined by the presence of a ≥50% stenosis in 0, 1, 2, or 3 coronary artery vessels.

Per-segment CAD severity was judged for individual coronary artery segments as we have previously described.15 Briefly, a segment stenosis score was calculated as a measure of the overall coronary artery plaque burden, and was graded and summed for each coronary segment as none to severe plaque (0–3) based on the extent of obstruction, with a total score ranging from 0 to 48. A segment involvement score was employed as a measure of overall coronary artery plaque distribution, and was calculated as the total number of coronary artery segments exhibiting plaque, irrespective of the degree of luminal stenosis within each segment (minimum = 0; maximum = 16). We further examined risk in association with any severe proximal stenosis in the left anterior descending, left circumflex, or right coronary vessels.

Clinical endpoints

The primary study endpoint was time to MACE, defined as death, MI and late revascularization (defined as >90 days after CCTA). Follow-up procedures were approved by all study centres’ IRB. The death status was gathered by clinical visits, telephone contacts, questionnaires sent by mail, or by query of the national death registry.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 12.0 (www.SPSS.com, Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS 9.2 (www.sas.com, Cary, NC, USA) were used for all statistical analyses. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and continuous variables as means ± 1 SD. Variables were compared with χ2 statistic for categorical variables and by Student's unpaired t test for continuous variables. Patients who underwent early revascularization procedures ≤90 days were excluded from all survival analyses. Time to event from all MACE events and event rates were calculated using univariable Cox proportional hazards models. In each case, the proportional hazards assumption was met. Adjusted models were also devised including multivariable stepwise models adjusting for baseline demographics, cardiac risk factors, typicality of angina and pre-test likelihood of obstructive CAD. Adjusted models were also developed to test first order interactions related to age and study site. A two-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study cohort

Among 17 226 consecutive patients undergoing CCTA at eight centres for whom the MACE follow-up and per-segment CAD data were available, 1110 patients with a history of MI, coronary revascularization, and cardiac transplant were excluded; and an additional 929 (5%) patients were lost to follow-up and excluded. The final analysis cohort consisted of 15 187 patients. The study cohort was middle-aged (57 ± 12 years, 55% male) with a high prevalence of CAD risk factors and symptoms. Patients presented predominantly with typical or atypical angina, with the majority of individuals intermediate or high pre-test likelihood of obstructive CAD. Given their history of prior CAD, excluded patients had a higher pre-test likelihood of CAD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the entire registry and study cohort

| Entire registry | Study cohort | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) or means ± SD | n (%) or means ± SD | |

| Total | 27 125 | 15 187 |

| Age* | 57.7 ± 12.7 | 56.8 ± 11.8 |

| Male gender | 14 997 (55) | 8363 (55) |

| Diabetes* | 4067 (15) | 1958 (13) |

| Diabetes/meds* | 4128 (15) | 2015 (13) |

| Family history of premature CAD* | 9849 (37) | 4431 (30) |

| Hyperlipidaemia* | 14 906 (56) | 8248 (55) |

| Hyperlipidaemia/meds* | 15 666 (58) | 8890 (59) |

| Hypertension* | 13 582 (51) | 7196 (48) |

| Hypertension/meds* | 16 084 (60) | 9353 (62) |

| Current smoker* | 4994 (19) | 2476 (16) |

| History of PAD/CVD* | 485 (4) | 354 (5) |

| Chest paina | ||

| Typical angina | 3556 (16) | 1468 (10) |

| Atypical angina | 8860 (39) | 6246 (43) |

| Non-cardiac | 2699 (12) | 1325 (9) |

| Asymptomatic | 7796 (34) | 5387 (37) |

| Pre-test CAD likelihoodb | ||

| Low <10% | 6477 (28) | 4485 (31) |

| Intermediate 10–90% | 14 137 (62) | 8849 (62) |

| High >90% | 2153 (9) | 967 (7) |

*P-value for differences in percentages for study cohort vs. excluded patients <0.05.

aTypicality of chest pain and pre-test likelihood of CAD missing from registry in 4214 patients and 4358, respectively.

Clinical characteristics associated with CAD and MACE

Survival was examined after a mean follow-up of 2.4 ± 1.2 years (median = 2.1, inter-quartile range 1.4–3.3 years), at which point 595 MACE events were recorded (182 deaths, 191 MI, 283 late revascularization). Among patients ≥65 vs. <65 years old, a higher incidence was observed for each individual component of MACE, including for all-cause mortality [122 (3.0%) vs. 60 (0.5%), P< 0.001], non-fatal MI [82 (2.0%) vs. 109 (1.0%), P < 0.001], and late revascularization [138 (3.4%) vs. 145 (1.3%), P < 0.001]. In the case of multiple event types, time to the earliest event constituted time to MACE. For the survival analyses, early revascularization was excluded and 507 MACE events were analysed. Increasing severity of CAD was associated with male gender, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, family history of CAD, current smoking, typical angina and high pre-test likelihood of CAD (P ≤ 0.002 for all) (Table 2). In univariable Cox proportional hazards models, increased hazards for MACE was associated with advanced age, male gender, diabetes, hypertension, untreated dyslipidaemia, current smoking, family history of CAD, and pre-test CAD likelihood (Table 3).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of study group stratified by normal, non-obstructive, and obstructive CAD by CCTA

| Normal | Non-obstructive CAD | Obstructive CAD | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 7015) | (n = 5374) | (n = 2798) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age, mean ± SD | 52.0 ± 11.6 | 60.0 ± 10.3 | 62.7 ± 10.1 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 3180 (45.4) | 3256 (60.6) | 1927 (68.9) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 611 (8.8) | 760 (14.2) | 587 (21.1) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 2836 (41.0) | 2694 (51.0) | 1666 (60.2) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 3284 (47.5) | 3107 (58.4) | 1857 (66.9) | <0.0001 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 1882 (27.5) | 1551 (29.6) | 998 (36.5) | <0.0001 |

| Current smoking | 1047 (15.1) | 830 (15.6) | 599 (21.6) | <0.0001 |

| Chest pain Typicalitya | <0.0001 | |||

| Typical | 580 (8.7) | 425 (8.3) | 463 (17.4) | |

| Atypical | 3314 (49.8) | 1994 (39.0) | 938 (35.2) | |

| Non-cardiac | 592 (8.9) | 479 (9.4) | 254 (9.5) | |

| Asymptomatic | 2168 (32.6) | 2211 (43.3) | 1008 (37.9) | |

| Pre-test CAD Likelihoodb | <0.0001 | |||

| Low | 2375 (36.0) | 1543 (30.4) | 567 (21.5) | |

| Intermediate | 3951 (59.9) | 3210 (63.3) | 1688 (64.0) | |

| High | 266 (4.0) | 318 (6.3) | 383 (14.5) | |

| Revascularization <90 days | 14 (0.2) | 58 (1.1) | 709 (25.3) | <0.0001 |

aChest pain typicality and bpre-test likelihood of CAD missing in 761 and 886 patients, respectively.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics associated with MACE event

| Variable | Univariable HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.07 (1.06–1.07) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 1.40 (1.17–1.68) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 2.34 (1.91–2.86) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2.01 (1.67–2.41) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1.41 (1.18–1.70) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking | 1.33 (1.07–1.65) | 0.01 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 1.45 (1.20–1.74) | <0.001 |

| Pre-test CAD Likelihood per 10% increments | 1.09 (1.06–1.13) | <0.001 |

CAD findings for patients experience MACE vs. No MACE

Compared with patients who did not experienced an MACE event at follow-up, patients who did experience an MACE event had significantly more severe CAD in the majority of coronary segments (Table 4).

Table 4.

Coronary artery stenosis severity by segment for individuals with MACE vs. without MACE

| Coronary segment | No MACE (n = 14 592) |

MACE (n = 595) |

P-value (%) | P-value (stenosis score) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % with any CAD | Stenosis score | n | % with any CAD | Stenosis score | |||

| Left main artery | 2227 | 16 | 0.17 ± 0.40 | 224 | 39 | 0.45 ± 0.63 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Left anterior descending artery | ||||||||

| Proximal | 5486 | 38 | 0.46 ± 0.67 | 410 | 73 | 1.17 ± 0.99 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Mid | 3938 | 29 | 0.38 ± 0.69 | 329 | 60 | 1.01 ± 1.05 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Distal | 1218 | 9 | 0.12 ± 0.41 | 146 | 27 | 0.41 ± 0.79 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Diagonal artery 1 | 1318 | 10 | 0.14 ± 0.47 | 144 | 29 | 0.47 ± 0.86 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Diagonal artery 2 | 583 | 5 | 0.07 ± 0.33 | 53 | 13 | 0.22 ± 0.64 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Left circumflex artery | ||||||||

| Proximal | 2380 | 17 | 0.20 ± 0.49 | 250 | 45 | 0.66 ± 0.88 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Distal | 1235 | 9 | 0.13 ± 0.45 | 156 | 30 | 0.47 ± 0.84 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Obtuse Marginal 1 | 922 | 7 | 0.10 ± 0.41 | 123 | 25 | 0.45 ± 0.90 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Obtuse Marginal 2 | 382 | 6 | 0.08 ± 0.37 | 50 | 20 | 0.31 ± 0.70 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Right coronary artery | ||||||||

| Proximal | 3015 | 21 | 0.26 ± 0.57 | 299 | 53 | 0.78 ± 0.93 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Mid | 2351 | 17 | 0.23 ± 0.58 | 267 | 50 | 0.84 ± 1.04 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Distal | 1465 | 11 | 0.15 ± 0.46 | 198 | 38 | 0.54 ± 0.83 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Right PL artery | 116 | 1 | 0.02 ± 0.17 | 11 | 4 | 0.07 ± 0.35 | <0.001 | 0.0003 |

| Left PL artery | 14 | 0.3 | 0.01 ± 0.11 | 3 | 3.5 | 0.08 ± 0.44 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Posterior descending artery | 494 | 4 | 0.05 ± 0.29 | 74 | 15 | 0.25 ± 0.67 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

Per-patient, per-vessel and per-segment CAD severity and risk of MACE

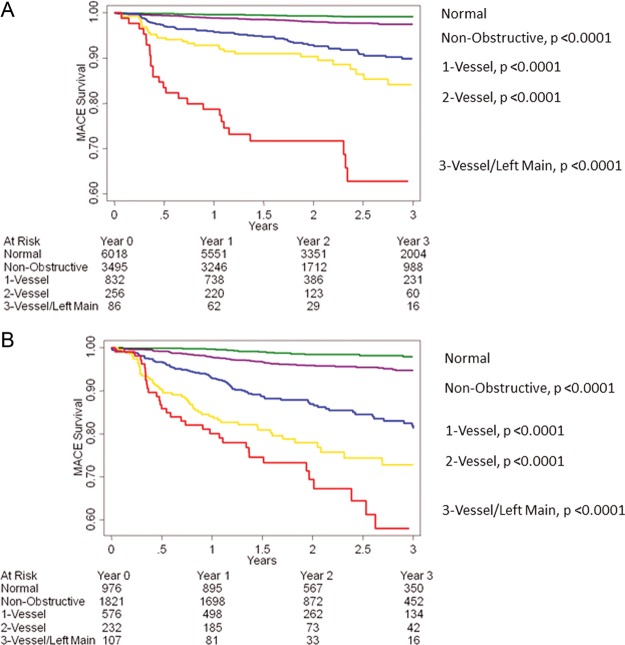

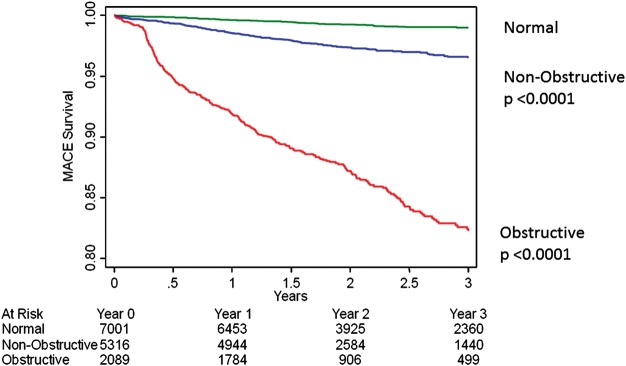

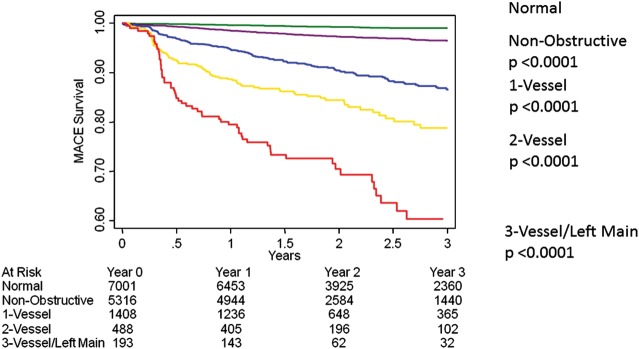

In both univariable as well as multivariable Cox regression analysis considering age, and CAD risk factors, MACE was predicted by maximal per-patient non-obstructive and obstructive CAD (Table 5, Figure 1). By both univariable and multivariable Cox models, per-vessel obstructive CAD was related to a dose–response increased hazards for MACE for one-vessel, two-vessel, three-vessel, or LM CAD (Table 5, Figure 2). Similarly, in both univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis, higher rates of incident MACE were associated with higher numbers of coronary segments with plaque, with stenosis-adjusted segments with plaque, with any severe proximal stenosis and with any plaque within the LM artery (Table 5). Sixty-two MACE events occurred in patients with no angiographic luminal narrowing by CCTA resulting in an annual event rate of 0.36% (Figure 1). On the other hand, 146 MACE events occurred in patients with non-obstructive CAD by CCTA resulting in an annual event rate of 1.22%, while there were 299 MACE events occurred in patients with obstructive CAD resulting in an annual event rate of 6.85%.

Table 5.

Univariable and adjusted hazards ratio for MACE events by per-patient, per-vessel and per-segment analysis by obstructive CAD

| CCTA Result | Univariable HR (95% CI) | P-value | Risk-adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per-patient analysis | ||||

| Normal (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Non-obstructive | 3.31 (2.46–4.46) | <0.001 | 2.43 (1.77–3.34) | <0.001 |

| Obstructive CAD | 18.40 (14.00–24.20) | <0.001 | 11.21 (8.26–15.22) | <0.001 |

| Per-vessel analysis | ||||

| Normal (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Non-obstructive | 3.31 (2.46–4.46) | <0.001 | 2.54 (1.85–3.49) | <0.001 |

| One-vessel obstructive | 13.57 (10.10–18.22) | <0.001 | 9.15 (6.62–12.63) | <0.001 |

| Two-vessel obstructive | 23.65 (17.04–32.82) | <0.001 | 15.00 (10.47–21.49) | <0.001 |

| Three-vessel or left main | 47.08 (32.99–67.19) | <0.001 | 24.53 (16.38–36.72) | <0.001 |

| Per-segment analysis | ||||

| Segment involvement score (per segment involved) | 1.31 (1.28–1.34) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.19–1.25) | <0.001 |

| Segment stenosis score (per segment severity) | 1.18 (1.16–1.19) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.12–1.15) | <0.001 |

| Presence of proximal stenosis | 5.30 (4.26–6.59) | <0.001 | 3.10 (2.44–3.94) | <0.001 |

| Presence of left main stenosis | 3.77 (3.13–4.53) | <0.001 | 2.19 (1.79–2.67) | <0.001 |

Hyperlipidaemia removed in multivariate analysis (P> 0.05).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted all-cause 3-year Kaplan–Meier MACE-free survival by the maximal per-patient presence of none, non-obstructive and obstructive CAD

Figure 2.

Unadjusted all-cause 3-year Kaplan–Meier MACE-free survival by the presence, extent and severity of CAD by CCTA.

Age-stratified impact of CCTA-visualized CAD on MACE from all-causes

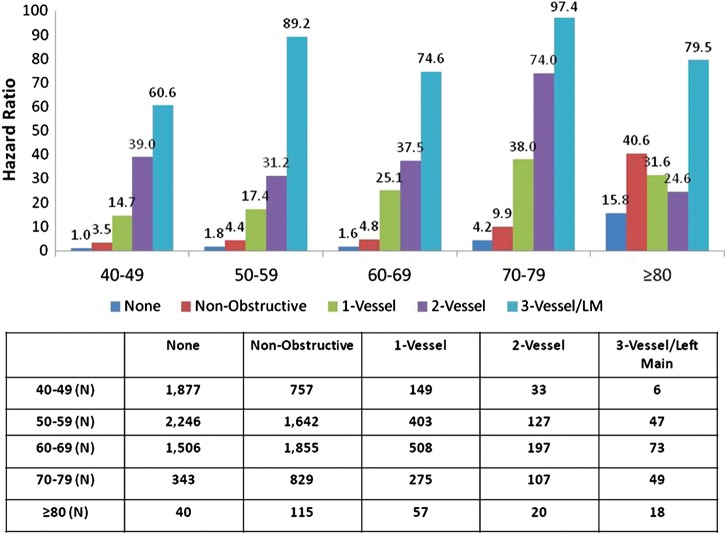

Individuals <65 years old had lower pre-test probability of CAD than those ≥65 years (pre-test probability low 36 vs. 18%; intermediate 59 vs. 69%, high 4 vs. 13%, χ2 P< 0.0001). When compared with individuals without CAD in patients <65 years, patients ≥65 years experienced higher hazards for MACE for non-obstructive, one-vessel, and two-vessel obstructive CAD than patients <65 years, with similar rates of MACE for three-vessel or left main obstructive CAD (Table 6, Figure 3). A dose–response relationship of MACE risk was observed per increasing decade of life (Figure 4).

Table 6.

Adjusted hazards ratio for MACE events for patients <65 vs. ≥65 years of age

| <65 years old |

≥65 years old |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Normal | 1.00 (reference) | – | 2.30 (1.29–4.11) | 0.005 |

| Non-obstructive | 2.70 (1.82–4.00) | <0.001 | 6.19 (4.22–9.07) | <0.001 |

| One-vessel Disease | 11.35 (7.65–16.85) | <0.001 | 19.89 (13.57–29.14) | <0.001 |

| Two-vessel Disease | 17.41 (10.87–27.90) | <0.001 | 36.06 (23.74–54.78) | <0.001 |

| Three-vessel disease or left main disease | 47.61 (28.46–79.66) | <0.001 | 48.10 (30.13–76.77) | <0.001 |

Figure 3.

Unadjusted all-cause 3-year Kaplan–Meier MACE-free survival by presence, extent and severity of CAD by CCTA as stratified by age <65 (A) or ≥65 (B) years of age.

Figure 4.

Unadjusted MACE hazard ratio based on decade of life.

We also separately compared the individual components of MACE including death, MI, and late revascularization among patients <65 and ≥65 years old (Table 7). All the individual components of MACE were higher for individuals ≥65 than <65 years for normal, non-obstructive, one-, two-, and three-vessel or left main obstructive CAD than patients <65 years (Table 7).

Table 7.

Adjusted hazards ratio for individual MACE events for patients <65 vs. ≥65 years of age

| Variable | <65 years old |

≥65 years old |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| Normal | 1.00 (reference) | 3.77 (1.82–7.81) | <0.001 | |

| Non-obstructive | 1.80 (0.95–3.39) | 0.07 | 7.49 (4.34–12.91) | <0.001 |

| One-vessel disease | 2.14 (0.85–5.40) | 0.11 | 14.24 (7.90–25.65) | <0.001 |

| Two-vessel disease | 6.92 (2.72–17.56) | <0.001 | 18.67 (9.21–37.83) | <0.001 |

| Three-vessel disease or left main disease | 6.35 (1.45–27.75) | 0.01 | 12.24 (4.50–33.31) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||

| Normal (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.94 (0.28–3.22) | 0.93 | |

| Non-obstructive | 2.71 (1.49–4.94) | 0.001 | 3.52 (1.83–6.76) | <0.001 |

| One-vessel disease | 4.15 (1.93–8.91) | <0.001 | 4.91 (2.18–11.03) | <0.001 |

| Two-vessel disease | 7.08 (2.75–18.22) | <0.001 | 12.46 (5.49–28.28) | <0.001 |

| Three-vessel disease or left main disease | 17.91 (6.40–50.13) | <0.001 | 13.09 (4.75–36.10) | <0.001 |

| Late revascularization | ||||

| Normal | 1.00 (reference) | 2.41 (0.47–12.45) | 0.29 | |

| Non-obstructive | 10.44 (4.06–26.87) | <0.001 | 14.62 (5.52–38.67) | <0.001 |

| One-vessel disease | 71.05 (28.29–178) | <0.001 | 94.50 (37.42–239) | <0.001 |

| Two-vessel disease | 104 (39.47–274) | <0.001 | 195 (76.09–501) | <0.001 |

| Three-vessel disease or left main disease | 334 (124–894) | <0.001 | 327 (125–856) | <0.001 |

Age-stratified impact of early vs. late revascularization

We examined whether symptom-driven early revascularization (≤90 days) incidence differed by age, and noted differences among individuals ≥65 vs. <65 years for typical angina (14.3 vs. 10.6%, P = 0.035), atypical angina (8.8 vs. 3.4%, P < 0.001), non-cardiac pain (9.7 vs. 3.1%, P < 0.001), and shortness of breath (7.6 vs. 4.7%, P = 0.001). When compared with individuals without CAD in patients with <65 years, patients with ≥65 years experienced higher hazards for MACE for late revascularization [hazard ratio (HR) 11.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 6.90–19.73, P = 0.002], while patients <65 years experienced higher hazards for MACE for late revascularization (HR: 17.73, 95% CI: 11.40–27.57, P = 0.002).

Discussion

In this present study, we observed an independent prognostic value of both non-obstructive and obstructive CAD for future MACE on a per-patient, per-vessel and per-segment basis. We further observed the risk of future MACE based on CAD findings by CCTA as it related to age, and identified a heightened risk for future MACE for individuals <65 vs. ≥65 years of age, even when adjusted for measures of CAD, when compared with their similar aged counterparts without evident CAD by CCTA. We further observed a dose–response relationship of MACE risk with each advancing decade of life. To our knowledge, the current study represents the first prospective large-scale multicentre international study to examine the incidence of MACE based on CCTA findings of CAD with adequate power (beta > 0.90, alpha > 0.001) to allow for differential age-related risk stratification based on CAD extent and severity by CCTA. These results are similar to prior studies, which have demonstrated that the extent and severity of ischaemia has previously been shown to be a poor prognostic indicator.16–21 Although, the ability of CCTA to detect anatomic coronary artery stenoses has been well established, prior studies have shown its inability to reliably detect haemodynamically significant CAD.22,23 Future studies are likely required to further assess the haemodynamic significance of these obstructive lesions on CCTA.

A recent study of 24 775 stable patients from CONFIRM registry assessed the prognostic value CCTA for the prediction of all-cause mortality.14 In this large, multicentre, multinational study, both non-obstructive (HR: 1.60, P = 0.002) and obstructive CAD (HR: 2.60, P < 0.0001) were associated with increased all-cause mortality, with differences in multivariable risk-adjusted hazards for all-cause mortality noted for non-obstructive as well as increasing degrees of obstructive CAD. Importantly, the risk of 4-year death in this study was very low, indicating a ‘warranty period’ associated with a normal CCTA. As applied to MACE, Yiu et al.24 assessed the prognostic significance of CCTA CAD findings for the prediction of MACE events in 2432 patients suspected of CAD. During 2.2-year follow-up, there were 59 (2.4%) MACE events, with significantly higher event rates noted in patients older than 60. The authors noted a dose-dependent increase in MACE risk based on the presence of CAD regardless of age or gender, with patients without evidence of CAD on CCTA having very low event rates (≤0.3%). These findings in are accordance with a recent meta-analysis applied to acute symptoms for which 1559 adult patients with symptoms suggestive of ACS underwent CCTA and were assessed for MACE at a ≥30 days after their initial presentation.25 This study demonstrated a ≥99% negative predictive valve of MACE based on the CCTA findings, suggesting the power of a normal CCTA to identify a low-risk population.

The findings of these prior studies are in general agreement with the present study results and support the notion of a very low-risk state for patients with normal coronary arteries by CCTA; as well as an increasing risk of future MACE for both non-obstructive and obstructive CAD. However, the results of the present study directly and substantively extend these prior findings by stratifying risk according to age. When dichotomized by age ≥65 vs. <65 years, patients <65 years old had lower hazards of MACE for non-obstructive, one-, and two-vessel CAD, when compared with those who were ≥65 years old, they had similar hazard rates for three-vessel and LM disease. When stratified based on individual components of MACE, younger patients with three-vessel or LM disease had higher hazard rates for MI and late revascularization compared with individuals ≥65 years old. The potential explanations for these findings are manifold, and may relate to more aggressive forms of atherosclerosis in younger patients with a greater extent and severity of CAD when compared with their age-related counterparts. Future studies examining the phenomena that underscore this increased risk should now be pursued.

Even when stratified in a more granular fashion—that is, according to increasing decade of life—we observed a dose–response relationship of CAD extent and severity to MACE. This relationship was generally linear in nature, but increased for patients ≥80 years. Conversely, we noted a very low MACE event rate for patients with normal coronary arteries by CCTA, even among older patients. Importantly, we noted higher MACE rates in the very elderly population even among those with non-obstructive CAD by CCTA. When examined for components of MACE, mortality dominated as an endpoint in this population and thus, it is conceivable that these increased death rates may represent those of a non-cardiac nature. Future studies with cause-specific endpoints may be useful to further describe these findings.

Limitations

While this study addresses many of the shortcomings of prior smaller single-centre investigations evaluating the prognostic performance of CAD findings by CCTA for the prediction of MACE, it is nevertheless not immune to measures of selection, referral, and misclassification bias, as is the case for all observational studies. The information regarding the downstream treatment based on CCTA findings were also unknown, and it remains possible that changes in medical therapy following CCTA may have altered study outcomes. However, salutary treatment regimens would most likely mitigate rather than strengthen the current study's findings. Given the increasing risk associated with CAD findings by CCTA—specifically as it relates to age—future prospective studies examining differential treatment strategies may be useful to further expound upon these present study findings. Furthermore, stress testing data were not available in our study cohort, and future studies are likely required to assess the haemodynamic significance of obstructive lesions on CCTA.

Conclusion

In this large, prospective, multinational, multicentre CONFIRM registry, extent, and severity of CAD by CCTA is independent predictor of future cardiovascular events, with age-specific differences in risk. Importantly, normal coronary arteries by CCTA are associated with a low risk of future MACE, irrespective of age.

Funding

Research was supported by NIH under the award number 401HL11511150-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest : none declared.

References

- 1.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–53. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part II: variations in cardiovascular disease by specific ethnic groups and geographic regions and prevention strategies. Circulation. 2001;104:2855–64. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams MA, Fleg JL, Ades PA, Chaitman BR, Miller NH, Mohiuddin SM, et al. Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in the elderly (with emphasis on patients > or =75 years of age): an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention. Circulation. 2002;105:1735–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013074.73995.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roversi S, Biondi-Zoccai G, Romagnoli E, Sheiban I, De Servi S, Tamburino C, et al. Early and long-term outlook of percutaneous coronary intervention for bifurcation lesions in young patients. Int J Cardiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.005. Sep 17 pii: S0167–5273(12)01093–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.005 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijboom WB, Meijs MFL, Schuijf JD, Cramer MJ, Mollet NR, van Mieghem CAG, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a prospective, multicenter, multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1724–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo V, Zavalloni A, Bacchi Reggiani ML, Buttazzi K, Gostoli V, Bartolini S, et al. Incremental prognostic value of coronary CT angiography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:351–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.880625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sozzi FB, Civaia F, Rossi P, Robillon J-F, Rusek S, Berthier F, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with first-time chest pain having 64-slice computed tomography. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:516–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min JK, Feignoux J, Treutenaere J, Laperche T, Sablayrolles J. The prognostic value of multidetector coronary CT angiography for the prediction of major adverse cardiovascular events: a multicenter observational cohort study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;26:721–8. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Werkhoven JM, Bax JJ, Nucifora G, Jukema JW, Kroft LJ, de Roos A, et al. The value of multi-slice-computed tomography coronary angiography for risk stratification. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009;16:970–80. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9144-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiraishi J, Kohno Y, Yamaguchi S, Arihara M, Hadase M, Hyogo M, et al. Medium-term prognosis of young Japanese adults having acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2006;70:518–24. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah MH, Berman DS, et al. Rationale and design of the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multicenter) Registry. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, et al. Age- and Sex-related differences in All-cause mortality risk based on coronary computed tomography angiography findings results from the international multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: an International Multicenter Registry) of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:849–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB, Okin PM, Weinsaft JW, Russo DJ, et al. Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1161–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw LJ, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, et al. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death: differential stratification for risk of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:535–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, Mancini GBJ, Hayes SW, Hartigan PM, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117:1283–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee DS, Verocai F, Husain M, Al Khdair D, Wang X, Freeman M, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes are predicted by exercise-stress myocardial perfusion imaging: impact on death, myocardial infarction, and coronary revascularization procedures. Am Heart J. 2011;161:900–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coelho-Filho OR, Seabra LF, Mongeon F-P, Abdullah SM, Francis SA, Blankstein R, et al. Stress myocardial perfusion imaging by CMR provides strong prognostic value to cardiac events regardless of patient's sex. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:850–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw LJ, Cerqueira MD, Brooks MM, Althouse AD, Sansing VV, Beller GA, et al. Impact of left ventricular function and the extent of ischemia and scar by stress myocardial perfusion imaging on prognosis and therapeutic risk reduction in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease: results from the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19:658–69. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9548-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farzaneh-Far A, Phillips HR, Shaw LK, Starr AZ, Fiuzat M, O'Connor CM, et al. Ischemia change in stable coronary artery disease is an independent predictor of death and myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:715–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Carli MF, Dorbala S, Curillova Z, Kwong RJ, Goldhaber SZ, Rybicki FJ, et al. Relationship between CT coronary angiography and stress perfusion imaging in patients with suspected ischemic heart disease assessed by integrated PET-CT imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2007;14:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hacker M, Jakobs T, Matthiesen F, Vollmar C, Nikolaou K, Becker C, et al. Comparison of spiral multidetector CT angiography and myocardial perfusion imaging in the noninvasive detection of functionally relevant coronary artery lesions: first clinical experiences. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1294–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yiu KH, de Graaf FR, Schuijf JD, van Werkhoven JM, Marsan NA, Veltman CE, et al. Age- and gender-specific differences in the prognostic value of CT coronary angiography. Heart. 2012;98:232–7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takakuwa KM, Keith SW, Estepa AT, Shofer FS. A meta-analysis of 64-section coronary CT angiography findings for predicting 30-day major adverse cardiac events in patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome. Acad Radiol. 2011;18:1522–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]