Abstract

Objective

To describe the successful treatment of severe noninsulinoma hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with use of a calcium channel blocking agent in an adult patient who had previously undergone a gastric bypass surgical procedure.

Methods

A 65-year-old woman who had undergone a gastric bypass surgical procedure 26 years earlier was hospitalized because of severe postprandial hypoglycemia. During and after hospitalization, the patient underwent assessment with conventional measurements of glucose, insulin, proinsulin, and C-peptide; toxicologic studies; magnetic resonance imaging studies of the pancreas; and determination of hepatic vein insulin concentrations after selective splanchnic artery calcium infusion.

Results

Metabolic variables were consistent with the diagnosis of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed the presence of a side branch intraductal papillary mucinous tumor that had been stable for more than 1 year. The results of the calcium-stimulated insulin release study were consistent with nonlocalized hypersecretion of insulin. A trial of frequent small feedings failed to prevent hypoglycemia. On the basis of reports of successful treatment of childhood nesidioblastosis, the patient was then prescribed nifedipine, 30 mg daily. She has subsequently remained free of symptomatic hypoglycemia for 20 months.

Conclusion

A calcium channel blocking agent may be efficacious and a potential alternative to partial pancreatectomy in cases of noninsulinoma hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in adults.

INTRODUCTION

Transient hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia is often observed as the result of overdosage with exogenous insulin or orally administered hypoglycemic agents. Persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (PHH) is uncommon. Solitary insulinomas are the classic cause of fasting hypoglycemia due to hyperinsulinemia (1). Although infrequent, insulinomas constitute the most common type of pancreatic islet neoplasm.

Nesidioblastosis (islet cell hyperplasia) is a rare form of nonmalignant islet cell adenomatosis that leads to insulin-mediated hypoglycemia. In infants, nesidioblastosis is typically characterized by islet hyperplasia, β-cell hypertrophy, and increased β-cell mass. It can be either diffuse or focal and is sometimes termed “persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy” (2–4). Many cases have a defined genetic basis (5). A few cases of nesidioblastosis have been reported in adults (5–7). In these cases, the pathologic findings are reportedly less consistent than in infants (8), and the cause of the disorder is unknown. Additional cases of PHH have been diagnosed in adults who had previously undergone a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgical procedure for weight reduction (9). Whether these cases represent nesidioblastosis (9,10) or a reactive process leading to or unmasking a defect in β-cell function (11) is unclear, perhaps in part because the pathologic diagnosis of nesidioblastosis is difficult (8).

Partial pancreatectomy has been the therapy of choice for PHH after gastric bypass (9). We report the case of a patient with a distant history of a gastric bypass procedure who had recurrent postprandial hypoglycemia associated with overproduction of insulin in all regions of the pancreas and who responded to treatment with a calcium channel blocking agent.

CASE PRESENTATION

Initial Observations

A 65-year-old woman lost consciousness while shopping, approximately 2 hours after she had eaten lunch. Emergency rescuers documented a finger-stick glucose concentration of 25 mg/dL, and the patient recovered after intravenous administration of 50% dextrose. Evaluation in the emergency department revealed no evidence of acute illness, and the patient was admitted for the first time to our institution for further evaluation. Her medical history included diagnoses of depression, neurosarcoidosis, Raynaud phenomenon, hypertension, postherpetic neuralgia, and pancreatitis subsequent to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Her surgical history was notable for a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure performed 26 years earlier, at which time her body mass index was 50 kg/m2. The procedure was complicated by obstruction of the small bowel and dumping syndrome that persisted for 1 year. Up to the time of the current admission, she had maintained a weight loss of about 45.4 kg (100 lb) after the gastric bypass procedure.

The patient’s medications on admission included only aspirin, multivitamins, docusate sodium, and fish oil. Examination of medications brought from her home revealed none associated with hypoglycemia. Review of systems was significant for 2 episodes of transient sweating, confusion, dizziness, light-headedness, and chest pressure during the preceding 2 months. Both episodes had occurred 1 to 2 hours after she had eaten breakfast. There was no history of use of insulin or orally administered hypoglycemic agents. Findings on physical examination were unremarkable except for surgical scars. Her body mass index was 31.5 kg/m2.

A screening study for sulfonylurea drugs in plasma was reported as “negative” (ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, Utah). The study tested for the following agents: chlorpropamide, tolazamide, acetohexamide, tolbutamide, glipizide, and glyburide. During a 36-hour fast, no symptomatic hypoglycemia was documented. During the entire hospitalization, 4 nonfasting finger-stick glucose determinations ranging from 38 to 45 mg/dL were noted, but laboratory measurements of glucose and insulin were not obtained until after the glucose concentration had risen to >60 mg/dL. Results of serum chemical studies, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, an adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test, and a 5-hour oral glucose tolerance test, were normal. The glucose nadir during the glucose tolerance test was 63 mg/dL at 3 hours.

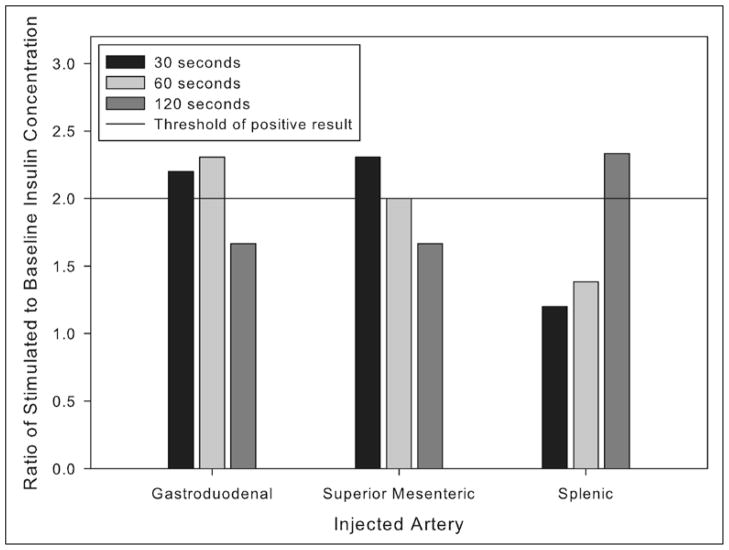

Abdominal ultrasonography showed normal findings. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pancreas revealed a nonenhancing serpiginous pancreatic parenchymal abnormality in the uncinate process, interpreted as a side branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Because of her postsurgical anatomy and previous pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, it was elected to follow the uncinate mass with serial imaging. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a program of frequent small feedings, and she was instructed to test her finger-stick glucose concentration in the event of symptoms.

Clinical Investigation

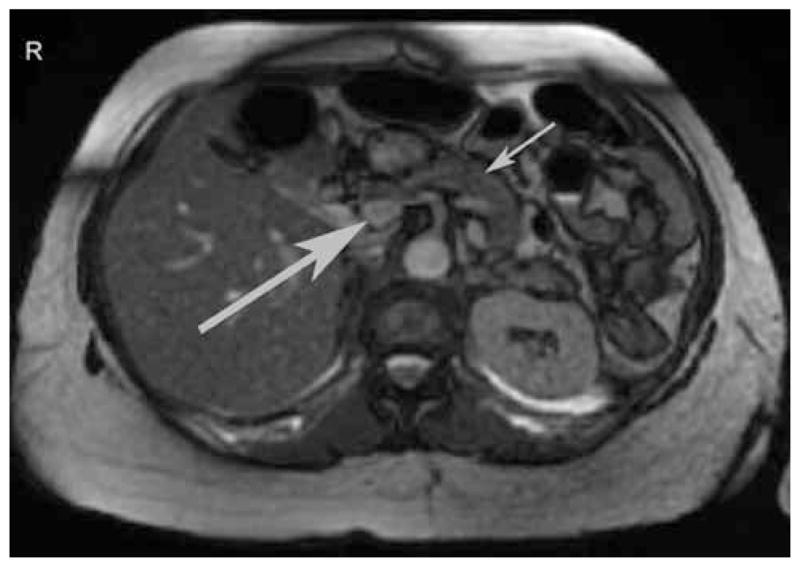

The patient continued to experience recurrent post-prandial symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, and her home glucose meter documented values in the range of 39 to 59 mg/dL. By chance, during a routine phlebotomy for health maintenance 3 months after her initial presentation, a laboratory glucose concentration of 39 mg/dL was noted. A concurrent insulin concentration was 18 μIU/mL (reference range, 6 to 27); a proinsulin concentration was 14.2 pmol/L (reference range, 2.1 to 26.8); and a C-peptide concentration was 5.5 ng/mL (reference range, 0.9 to 7.1). The patient was contacted, and she reported that symptoms suggestive of hypoglycemia had occurred after she left the phlebotomy station and had been relieved by ingestion of food. A provisional diagnosis of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after gastric bypass was made. Repeated magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen at that time showed no progression of the uncinate process lesion and no other mass in the pancreas (Fig. 1). For confirmation of the diagnosis and exclusion of an insulinoma, selective intra-arterial stimulation with calcium was performed, as previously described (9,12). The results were consistent with diffuse, nonlocalized hypersecretion of insulin (12,13) (Fig. 2). Arteriography during the calcium-stimulated insulin release study again showed no progression of the uncinate process lesion and no other mass in the pancreas.

Fig. 1.

Representative magnetic resonance image of the abdomen of the study patient, performed 3 months after her initial presentation. The larger arrow indicates a 1.8-cm focal serpiginous signal abnormality in the pancreatic head that extends to the uncinate process. It was interpreted as most likely representing a side branch intraductal papillary mucinous tumor. The smaller arrow indicates the distal portion of the pancreas. In comparison with prior studies, the lesion appeared not to have changed during the previous 2 years.

Fig. 2.

A calcium-stimulated insulin release study was performed, as described previously (12). Briefly, with the patient under conscious sedation, each of the indicated arteries supplying the pancreas was cannulated and injected with 0.025 mEq of calcium per kg of body weight. Blood samples for determination of insulin concentrations were obtained from a catheter in the right hepatic vein immediately before and then 30, 60, and 120 seconds after injection of the calcium solution. Shown are the ratios of stimulated to baseline insulin concentration for each arterial injection at each time point. Ratios of 2 or greater are considered a positive response that is indicative of hypersecretion of insulin (12,13). An abnormal response restricted to 1 region of the pancreas is suggestive of an insulinoma; abnormal responses in multiple regions are suggestive of diffuse hypersecretion, as has been observed in cases of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after a gastric bypass surgical procedure (9).

Subsequent Course

In light of the patient’s history of multiple surgical procedures and surgical complications, she was extremely reluctant to consider additional surgical intervention. Because calcium channel blocking agents have reportedly been successful in the treatment of PHH of infancy (14–16), the patient agreed to a trial of nifedipine titrated to a final dosage of 30 mg daily of a sustained-release formulation. Before initiation of treatment, her home glucose monitor recorded 8 readings <60 mg/dL during a 78-day period. Since the initiation of nifedipine therapy, the patient has reported no further episodes of postprandial symptoms through 20 months of observation. Periodic downloads of her home glucose meter have revealed no values <60 mg/ dL. Her mean outpatient blood pressure was 127/67 mm Hg (N = 5) before initiation of nifedipine treatment and 121/78 mm Hg (N = 9) subsequently (no significant difference for both systolic and diastolic pressures by a 2-sample t test). The patient experienced occasional mild orthostatic hypotension and constipation after starting nifedipine therapy (10 mg 3 times daily), but both side effects remitted substantially after the change to the sustained-release formulation of nifedipine, 30 mg daily. She has been instructed to rise to an upright posture slowly and to increase the fiber in her diet, and at month 20 of treatment she described both symptoms as mild and infrequent.

DISCUSSION

The available imaging and physiologic data suggest that this patient’s diagnosis is most likely noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia syndrome or organic persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (13,17). This conclusion is based on several lines of evidence. Her initial presentation fulfilled the classic Whipple criteria for the diagnosis of hypoglycemia. The observation of inappropriately elevated insulin and C-peptide concentrations in the context of a serum glucose concentration of 39 mg/dL established a diagnosis of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia not due to exogenous insulin. The angiographic findings and the results of the calcium stimulation test argue strongly against the diagnosis of insulinoma.

The condition of PHH in adults is rare; through 2008, only about 100 documented cases had been reported (8). The case ascertainment rate may be increasing, however, inasmuch as PHH is currently being recognized more frequently in patients who have undergone a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgical procedure. The cause of hypoglycemia in these patients is disputed, being ascribed variously to nesidioblastosis (9) or diffuse β-cell hyperplasia (10), dumping syndrome (11), and the induction or unmasking of a β-cell defect that leads to inappropriately increased insulin secretion (11). A possible explanation of the β-cell hyperfunction is that, with rapid gastric emptying and rapid presentation of chyme to the terminal ileum, excess glucagonlike peptide 1 is produced, stimulating the growth of insulin-producing islet cells (9,10,18).

Whatever the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism, it is important to note that, to our knowledge, such cases have uniformly been treated surgically (9,10). We are aware of 1 trial with octreotide in 3 patients, but each of these patients eventually underwent operative treatment (10). Diazoxide has also been used but without notable success (6). The combination of verapamil and acarbose has been reported to be effective, but documentation of PHH and durability of the therapy are incompletely documented in this case (19). Although partial pancreatectomy is highly effective in terminating episodes of hypoglycemia, insulin-requiring diabetes may subsequently develop in up to 40% of such patients (20). The patient described in our report was opposed to surgical treatment. Because nifedipine is reported to be useful in the management of nesidioblastosis in infants (14,15), this therapy was tried in our patient, who had a remarkably good outcome through 20 months of follow-up.

CONCLUSION

We recognize that PHH in adults appears to represent a heterogeneous set of incompletely understood phenomena. Even within this set of patients, our case is atypical, having the onset of symptoms 26 years after gastric bypass and also having the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis and an intercurrent intraductal papillary mucinous tumor. Furthermore, on several occasions, the patient was remarkably either minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic in the setting of a glucose concentration <50 mg/dL. It is interesting to speculate that her hypoglycemia had developed slowly, perhaps long before presentation, and had led to a blunting of adrenergic and neuroglycopenic responses. We recognize that a tissue diagnosis is lacking. Nonetheless, the remarkable response of this patient to a calcium channel blocking agent suggests that medical therapy for PHH in an adult patient may be a viable alternative to surgical intervention.

Abbreviation

- PHH

persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.De Herder WW. Insulinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80(suppl 1):20–22. doi: 10.1159/000080735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaczirek K, Niederle B. Nesidioblastosis: an old term and a new understanding. World J Surg. 2004;28:1227–1230. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7598-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperling MA, Menon RK. Differential diagnosis and management of neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:703–723. x. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fournet JC, Junien C. Genetics of congenital hyperinsulinism. Endocr Pathol. 2004;15:233–240. doi: 10.1385/ep:15:3:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raffel A, Krausch MM, Anlauf M, et al. Diffuse nesidioblastosis as a cause of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in adults: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Surgery. 2007;141:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rinker RD, Friday K, Aydin F, Jaffe BM, Lambiase L. Adult nesidioblastosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1784–1790. doi: 10.1023/a:1018844022084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anlauf M, Wieben D, Perren A, et al. Persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in 15 adults with diffuse nesidioblastosis: diagnostic criteria, incidence, and characterization of beta-cell changes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:524–533. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000151617.14598.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klöppel G, Anlauf M, Raffel A, Perren A, Knoefel WT. Adult diffuse nesidioblastosis: genetically or environmentally induced? Hum Pathol. 2008;39:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Service GJ, Thompson GB, Service FJ, Andrews JC, Collazo-Clavell ML, Lloyd RV. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with nesidioblastosis after gastric-bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:249–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patti ME, McMahon G, Mun EC, et al. Severe hypoglycaemia post-gastric bypass requiring partial pancreatectomy: evidence for inappropriate insulin secretion and pancreatic islet hyperplasia. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2236–2240. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1933-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier JJ, Butler AE, Galasso R, Butler PC. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after gastric bypass surgery is not accompanied by islet hyperplasia or increased beta-cell turnover. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1554–1559. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doppman JL, Chang R, Fraker DL, et al. Localization of insulinomas to regions of the pancreas by intra-arterial stimulation with calcium [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:734] Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:269–273. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Service FJ, Natt N, Thompson GB, et al. Noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia: a novel syndrome of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in adults independent of mutations in Kir6.2 and SUR1 genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1582–1589. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.5.5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanbag P, Pathak A, Vaidya M, Shahid SK. Persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy—successful therapy with nifedipine. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:271–272. doi: 10.1007/BF02734240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bas F, Darendeliler F, Demirkol D, Bundak R, Saka N, Gunöz H. Successful therapy with calcium channel blocker (nifedipine) in persistent neonatal hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1999;12:873–878. doi: 10.1515/jpem.1999.12.6.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindley KJ, Dunne MJ, Kane C, et al. Ionic control of beta cell function in nesidioblastosis: a possible therapeutic role for calcium channel blockade. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:373–378. doi: 10.1136/adc.74.5.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson GB, Service FJ, Andrews JC, et al. Noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia syndrome: an update in 10 surgically treated patients. Surgery. 2000;128:937–944. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.110243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brubaker PL, Drucker DJ. Minireview: glucagon-like peptides regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis in the pancreas, gut, and central nervous system. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2653–2659. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreira RO, Moreira RB, Machado NA, Gonçalves TB, Countinho WF. Post-prandial hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery: pharmacological treatment with verapamil and acarbose. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1618–1621. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witteles RM, Straus FH, II, Sugg SL, Koka MR, Costa EA, Kaplan EL. Adult-onset nesidioblastosis causing hypoglycemia: an important clinical entity and continuing treatment dilemma. Arch Surg. 2001;136:656–663. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]