Abstract

Although the olfactory system is not generally associated with seizures, sharp application of odor eliciting activity in a large number of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) has been shown to elicit seizures. This is most likely due to increased ictal activity in the anterior piriform cortex— an area of the olfactory system that has limited GABAergic interneuron inhibition of pyramidal output cell activity. Such hyperexcitability in a well-characterized and highly accessible system makes olfaction a potentially powerful model system to examine epileptogenesis.

1. Introduction

Epilepsy, a chronic neurological disorder characterized by seizures, affects 1–2% of the population [1–5]. Caused by a variety of pathologies, epilepsy is not considered a single disease or condition [1–5]. The most common form of epilepsy is temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), which is associated (in both humans and rodents) with ictal activity. This activity is characterized by abnormal long-lasting partial seizures caused by hypersynchronous, neuronal activity that can secondarily generalize from shorter lasting interictal spikes (see examples of ictal activity and interictal spikes in Fig. 1). Typically, in TLE, seizures and convulsions appear after a latent period following the initial injury and may progressively increase in frequency for much of the patient’s life. Seizures can become refractory to conventional anticonvulsant drug treatment, resulting in high morbidity and/or mortality for these patients [6–9]. TLE is associated with hippocampal sclerosis and mossy fiber sprouting in the inner molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (e.g., [10, 11]). These anatomical changes may also include reorganization of neurotransmitters and neuromodulator circuits [10], and may be coupled with abnormalities in inhibitory neurotransmission [12–15]. Previous studies that used electric cortical stimulation in TLE human subjects [16] or that altered excitation and/or inhibition pharmacologically in TLE animal models have shown increased inhibition that effectively suppresses epileptic spikes and seizures (e.g., [17–22]). Appropriate animal models for interictal spikes [18, 22] and chemical or electrical induction of status epilepticus (e.g., [23–25]) are essential for unraveling the complex mechanisms of epileptogenesis.

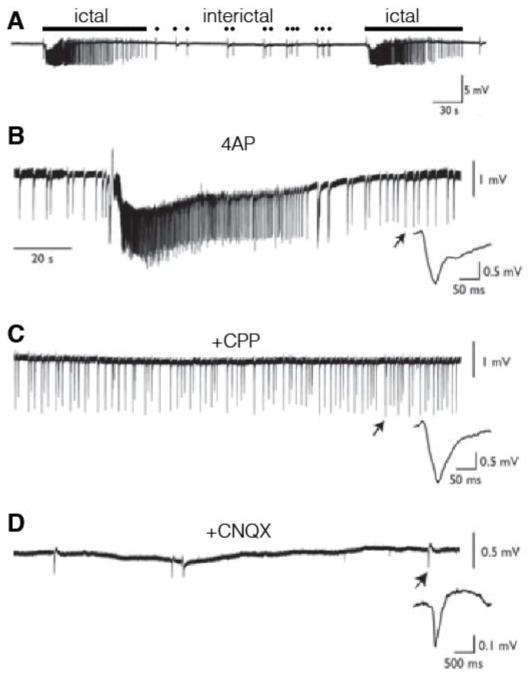

Fig. 1.

Examples of extracellularly recorded ictal activity and ictal spikes in piriform (from Fig 1 of Panuccio et al 2012 [65]). A. Example of ictal (long bar) and interictal (dots) activity. B. The K+ channel inhibitor 4-AP augments ictal activity. B. Addition of CPP with 4-AP inhibits ictal activity C. Addition of CNQX inhibits interictal spikes.

In a subset of human TLEs, complex partial seizures are followed by olfactory hallucinations (olfactory aura)[26–28]. These auras appear to involve the piriform cortex, a primary olfactory cortex, which generates so called “uncinate fits”. Interestingly, with sufficient warning of an oncoming seizure, a subset of patients can often prevent the seizure by smelling an odor. Importantly the piriform cortex projects to amygdala and lateral entorhinal cortex [29–31] (Fig. 2), brain structures well known to be involved in limbic seizures in patients with TLE [3, 32, 33]. Here, we review recent studies of the involvement of the olfactory system in generation of seizure.

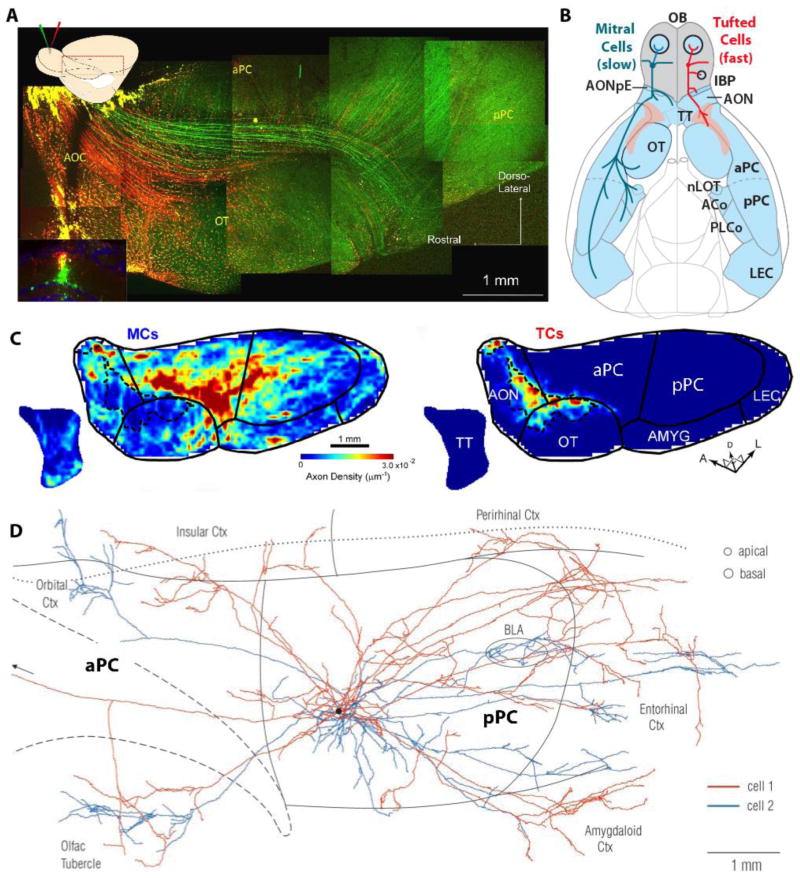

Fig. 2.

Projection of MT and TCs from the olfactory bulb (A–C) to: anterior olfactory cortex (AOC), piriform cortex (anterior, aPC and posterior pPC), olfactory tubercle (OT), tenia tecta (TT), amygdala (AMYG) and lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC). From: [29]. A. Inset: Coronal image of the tracer injection site in the OB. Dextran-conjugated Alexa 488 (green) and Alexa 594 (red) were injected into the deep and superficial parts of the EPL, respectively, in the dorsal OB [29]. The majority of the red-labeled neurons were TCs, and most green-labeled cells were MCs. DAPI nuclear labeling is blue. Main figure: Targeting of green-labeled presumed MC axons and red-labeled presumed TC axons. B. The axonal projections of the two cell types are represented on the left (MCs, blue) and right (TCs, red) sides of the diagram of the ventral-viewed mouse brain. C. Averaged axon density maps in the OC for MCs (left) and TCs (right). D. Association (cortico-cortical) axons from a pair of neighboring superficial pyramidal cells in aPC (from [70]). The arborizations from the second cell (blue) in the orbital cortex (top left) and basolateral amygdala (BLA, oval) are deep to piriform cortex. The black spot indicates the position of the cell bodies. The circles at top right denote typical diameters of pyramidal cell dendritic trees at the depths where they are contacted by association fibers (proximal apical dendrites in layer Ib and basal dendrites in layer III). The borders of piriform cortex and the insular-perirhinal border are indicated by solid lines; the dashed line outlines the lateral olfactory tract; the dotted line is the rhinal sulcus.

2. Experimental models of TLE

Spontaneous CA3 bursts can serve as an in-vitro model for interictal spikes. CA3 bursting resembles the abnormal synchronous interictal activity that are a hallmark of human TLE [34]. The hippocampal CA3 region has naturally occurring recurrent excitatory connections, which can produce “bursting” if GABAA inhibition is removed, extracellular potassium is increased, or high-frequency stimulation is presented [35–41].

The kainate- or pilocarpine-treated rat serves as an animal model for TLE. Kainate or pilocarpine can be injected into the rodent brain to induce hyperexcitability, producing seizures and/or status epilepticus [22, 25, 42]. Following the initial injury, these animals develop anatomical (hippocampal sclerosis and mossy fiber sprouting), behavioral (spontaneous seizures) and electrographic (interictal spikes and seizures) symptoms of TLE that last the lifetime of the animal.

The kindling model is another in-vivo model of TLE [43, 44]. This model is based upon the idea that “seizures beget seizures” [45]. It is hypothesized that through a positive feedback mechanism, a localized epileptiform discharge will spread to other cortical regions. In general, focal electrical stimulation in the brain produces a seizure (after discharge) that is short in duration with minimal behavioral manifestations [46, 47]. With repeated stimulations (e.g., twice daily), seizure duration increases along with more severe behavioral convulsions [46, 47]. This process produces localized electrically-induced seizures and creates a progression of seizure duration and severity that allows for investigation into the mechanisms of epileptogenesis.

3. In the olfactory system the piriform cortex is prone to seizures

The olfactory system discriminates between complex odors using ~1000 olfactory receptors (OR). Each olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) expresses only one olfactory receptor type from this repertoire of 1000 OR genes [48–50]. OSNs that express the same OR synapse in one or two glomeruli onto the primary dendrites of mitral and tufted (M/T) cells—the output neurons of the OB. In the last decade, research findings have significantly advanced our understanding of olfactory signal processing [30, 51–54]. In the glomerular layer of the OB, M/T neuronal output is inhibited by periglomerular (PG) and modulated by short axon cells. In the external plexiform layer of the OB, M/T output is inhibited by granule cell interneurons that reciprocally synapse onto M/T secondary dendrites. Mitral cell (MC) axons target several different brain areas including the piriform cortex (anterior and posterior), amygdala, and entorhinal cortex. In contrast, tufted cells (TCs) tend to target anterior olfactory nucleus/cortex and olfactory tubercle (Fig. 2). In the piriform cortex, MC input is integrated by the pyramidal output neurons. The integration of this input is restricted to only a few milliseconds due to the fast inhibitory activity of GABAergic interneurons [55, 56]. Interestingly, the anterior piriform cortex (aPC) exhibits a pronounced gradient of inhibitory activity such that rostrally (anteriorly) located pyramidal neurons receive less inhibition [57]. Because the mitral cells (MCs) send a substantially larger number of axons to the aPC compared to the tufted cells (TCs) (Fig. 2)[58] limiting MC input to pyramidal cells in this region is likely an important strategy in preventing seizures.

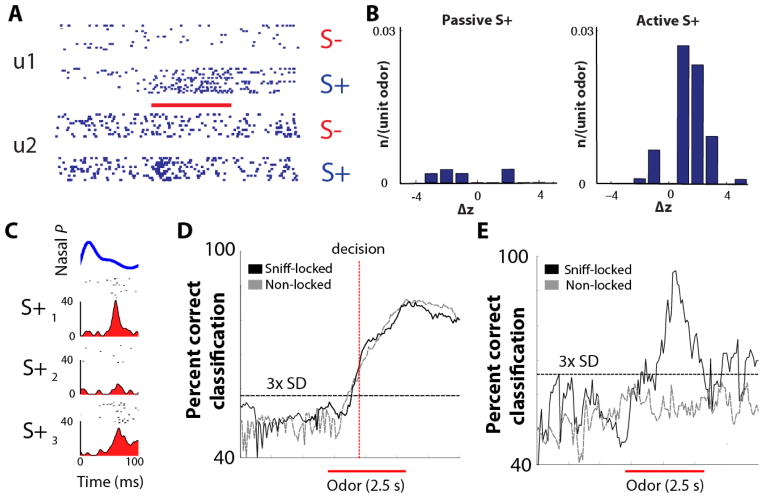

When mice passively detect odors (i.e. when they do not pay direct attention to the smell), aPC pyramidal cells do not significantly increase firing rates [59]. Similarly, in humans, passively detected odors result in minor neural activity in the aPC as assayed by fMRI [60, 61]. Thus, passive detection of odorants does not significantly increase the overall odor-induced firing rate of sniffed-locked pyramidal cells in the piriform cortex [59] and expends minimal use of cellular energy. In contrast, during the active detection of odorants (when the individual is actively interested in decision-making for the odor), the overall odor-induced firing rate of pyramidal cells does significantly increase (Fig. 3)[59]. These increases are metabolically demanding and could potentially result in seizure generation. Such seizure generation could be especially problematic in the aPC where GABAergic inhibition is markedly reduced as compared to the posterior piriform cortex [57]. Such reduced inhibition burdens the rostral aPC with increased metabolic demand in response to active odor detection. Finally, centrifugal feedback from pyramidal cells to OB GABAergic granule cells inhibits MCs [62], and likely serves as an important brake on pyramidal cell over-stimulation by MCs [63]. Neurons in the anterior olfactory nucleus/cortex similarly function as another centrifugal inhibitory feedback signal on M/T cells [64]. These feedback pathways are likely key in preventing substantial activity in MCs and thereby decrease the output that could generate seizures in the anterior piriform cortex.

Fig. 3.

Information for decision-making and stimulus identification is multiplexed in neurons in aPC (figure is from [59]). A. Raster plots of the action potential activity of two aPC cells (unit 1 and unit 2) during odor-induced responses in an active odor-detection task. The mouse is rewarded with water if it responds to the S+, rewarded odor, but not when it responds to S−, the unrewarded odor. Thick red line: time for odor exposure for 2.5 sec. B. Histogram for response magnitude (odor-induced change in z-score: Δz) in responsive units for rewarded (S+) odors. Note the large difference in responsive neurons in active vs. passive tasks (in a passive task the animal receives water regardless of which odor is present). C. Example of odor-induced firing within a sniff. Top, average sniff pressure transient. Time = 0: transition from exhalation to inhalation. Bottom, raster plots and integrated spike histograms within the sniff. Note that for different odors (S+1, S+2 and S+3) the neuron responded differentially. D–E. Black trace indicates time course for ideal observer discrimination performance calculated from the sniff-locked rate changes for different odors (S+ versus S− in d and S+1 versus S+2 in e). Red bar indicates odor presentation. Broken gray lines show that randomizing firing across sniffs eliminates all sniff-locked information in E but not in D. Task conditions: Active task, S+ versus S− (d) and passive task, S+ odor 1 versus S+ odor 3 (e).

4. Ictal activity and interictal spikes in the piriform cortex

Anterior and/or central piriform cortices have ictogenic properties [65–67]. Application of a convulsant K+ channel inhibitor (4-aminopyridine, 4-AP) to the piriform results in substantial, ictal-like discharges in the anterior (but not posterior) cortex, consistent with weaker interneuronal GABAergic inhibition in the aPC [65, 67](Fig. 1). This induced ictal activity initially includes high frequency oscillations (HFOs) ranging from 80–200 Hz. These HFOs might reflect the interaction between pyramidal and interneuronal network activity [65]. The ictal activity is likely mediated by NMDA-mediated transmission as evidenced by inhibition by the competitive antagonist 3,3-(2-carboxypiperazine-4-yl)propyl-1-phosphonate (CCP) (Fig. 1). In contrast, interictal activity did not display a preferential site of origin along the anterior-posterior axis in piriform cortex and was affected by α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)/kainate receptor antagonism by 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) (Fig. 1).

5. Strong olfactory input can elicit seizures in piriform cortex and other cerebral areas

OiS mice express the rat I7 olfactory receptors (responsive to octanal) in 90% of the OSNs [68]. When these mice are rapidly exposed to 1–10% octanal, a significant fraction of these mice display tonic-clonic seizures. Interestingly, a subset of these mice did not exhibit seizures, while another subset showed major tonic-clonic seizures that caused the mice to collapse backwards before repeatedly rearing. After octanal exposure, the OSN in the olfactory epithelium of OiS mice exhibited high levels of activity (as assayed through through in situ hybridization of c-fos expression) regardless of seizure outcome (Fig. 4B–C). In sharp contrast, neurons in the olfactory bulb, piriform cortex and the rest of the brain exhibited strong c-fos expression only in those mice that showed strong seizures (Fig. 4). Importantly, octanal did not elicit seizures when the odor concentration was slowly increased—even to the same concentration that elicited seizures during fast exposure. Thus, this study demonstrated that odor-induced sudden increases in a large number of glomeruli in the olfactory bulb can elicit seizures.

Fig. 4.

Data from Nguyen and Ryba [68] showing olfactory tissue c-fos in situ for OiS and control mice exposed to the I7 olfactory receptor activator octanol. A–C. c-fos in situ expression in the olfactory epithelium. Columns: Control mice, OiS mice that do not display seizures when exposed to the odor, and OiS mice that display a strong seizure when exposed to octanal. D. GFP-fluorescence (green) in a coronal section through the main olfactory bulb of an OiS-mouse counterstained with DAPI (gray) demonstrates that all glomeruli contained GFP-positive fibers whose expression was driven by the rat I7 olfactory receptor promoter. E–G. c-fos in situ in the olfactory bulb. H. Quantitation of the c-fos in situ in the MCs. I–K. c-fos in situ in piriform cortex. L. Quantitation of the c-fos in situ in anterior piriform cortex cells. Bars are 50 μm for A–C and 500 μm for E–G and I–K. **denotes p<0.01.

In a recent, intriguing study, a one-week exposure to an artificially odorized environment narrowed the range of odorants that can induce neurotransmitter release from olfactory sensory neurons and furthermore reduced the total transmitter release from responsive neurons [69]. This result raises the question of whether such a large decrease in olfactory input lowers the likelihood of the odor eliciting seizures. Future studies are necessary to better understand how odors elicit seizures and whether the olfactory system adapts to odors to minimize odors eliciting seizures.

6. Conclusions

Strong and rapid odor stimulation can elicit seizures. Downstream, the anterior piriform cortex has relatively small GABAergic interneuron inhibition of pyramidal cells, which likely gives this cortex ictogenic properties. These combined properties of the olfactory system makes for a powerful model system for the investigation of epilepsy.

Highlights.

Limited GABAergic inhibition in anterior piriform cortex increases seizure likelihood from excessive olfactory input

Sudden odor-induced activity in the olfactory bulb generates seizures spreading through the brain

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported by NIH grants DC00566 and DC006070 (DR).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Annegers JF. The epidemiology of epilepsy. In: Wyllie E, editor. The treatment of epilepsy: principles and practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 131–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benbadis SR. Epileptic seizures and syndromes. Neurol Clin. 2001;19:251–70. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang BS, Lowenstein DH. Epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1257–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engel J., Jr Surgery for seizures. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:647–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603073341008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson PD, French JA, Thadani VM, Kim JH, Novelly RA, Spencer SS, Spencer DD, Mattson RH. Characteristics of medial temporal lobe epilepsy: II. Interictal and ictal scalp electroencephalography, neuropsychological testing, neuroimaging, surgical results, and pathology. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:781–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodie MJ. Diagnosing and predicting refractory epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2005;181:36–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:314–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stables JP, Bertram E, Dudek FE, Holmes G, Mathern G, Pitkanen A, White HS. Therapy discovery for pharmacoresistant epilepsy and for disease-modifying therapeutics: summary of the NIH/NINDS/AES models II workshop. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1472–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.32803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devinsky O. Patients with refractory seizures. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1565–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905203402008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lanerolle NC, Brines M, Williamson A, Kim JH, Spencer DD. Neurotransmitters and their receptors in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;7:235–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malmgren K, Thom M. Hippocampal sclerosis--origins and imaging. Epilepsia. 2012;53 (Suppl 4):19–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen AS, Lin DD, Quirk GL, Coulter DA. Dentate granule cell GABA(A) receptors in epileptic hippocampus: enhanced synaptic efficacy and altered pharmacology. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1607–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02597.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lund IV, Hu Y, Raol YH, Benham RS, Faris R, Russek SJ, Brooks-Kayal AR. BDNF selectively regulates GABAA receptor transcription by activation of the JAK/STAT pathway. Sci Signal. 2008;1:ra9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1162396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayin U, Osting S, Hagen J, Rutecki P, Sutula T. Spontaneous seizures and loss of axo-axonic and axo-somatic inhibition induced by repeated brief seizures in kindled rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2759–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02759.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang N, Wei W, Mody I, Houser CR. Altered localization of GABA(A) receptor subunits on dentate granule cell dendrites influences tonic and phasic inhibition in a mouse model of epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7520–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1555-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinoshita M, Ikeda A, Matsuhashi M, Matsumoto R, Hitomi T, Begum T, Usui K, Takayama M, Mikuni N, Miyamoto S, Hashimoto N, Shibasaki H. Electric cortical stimulation suppresses epileptic and background activities in neocortical epilepsy and mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:1291–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bender RA, Soleymani SV, Brewster AL, Nguyen ST, Beck H, Mathern GW, Baram TZ. Enhanced expression of a specific hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel (HCN) in surviving dentate gyrus granule cells of human and experimental epileptic hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6826–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06826.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diao L, Hellier JL, Uskert-Newsom J, Williams PA, Staley KJ, Yee AS. Diphenytoin, riluzole and lidocaine: Three sodium channel blockers, with different mechanisms of action, decrease hippocampal epileptiform activity. Neuropharmacology. 2013;73C:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grabenstatter HL, Dudek FE. A new potential AED, carisbamate, substantially reduces spontaneous motor seizures in rats with kainate-induced epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1787–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grabenstatter HL, Clark S, Dudek FE. Anticonvulsant effects of carbamazepine on spontaneous seizures in rats with kainate-induced epilepsy: comparison of intraperitoneal injections with drug-in-food protocols. Epilepsia. 2007;48:2287–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grabenstatter HL, Ferraro DJ, Williams PA, Chapman PL, Dudek FE. Use of chronic epilepsy models in antiepileptic drug discovery: the effect of topiramate on spontaneous motor seizures in rats with kainate-induced epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2005;46:8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.13404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellier JL, White A, Williams PA, Edward Dudek F, Staley KJ. NMDA receptor-mediated long-term alterations in epileptiform activity in experimental chronic epilepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertram E. The relevance of kindling for human epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48 (Suppl 2):65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staley K, Hellier JL, Dudek FE. Do interictal spikes drive epileptogenesis? Neuroscientist. 2005;11:272–6. doi: 10.1177/1073858405278239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller CJ, Bankstahl M, Groticke I, Loscher W. Pilocarpine vs. lithium-pilocarpine for induction of status epilepticus in mice: development of spontaneous seizures, behavioral alterations and neuronal damage. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;619:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong SC, Holbrook EH, Leopold DA, Hummel T. Distorted olfactory perception: a systematic review. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132 (Suppl 1):S27–31. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2012.659759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acharya V, Acharya J, Luders H. Olfactory epileptic auras. Neurology. 1998;51:56–61. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Shih YH, Yen DJ, Lirng JF, Guo YC, Yu HY, Yiu CH. Olfactory auras in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44:257–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.25902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagayama S, Enerva A, Fletcher ML, Masurkar AV, Igarashi KM, Mori K, Chen WR. Differential axonal projection of mitral and tufted cells in the mouse main olfactory system. Front Neural Circuits. 2010:4. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2010.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shepherd GM, Chen WR, Greer CA. Olfactory bulb. In: Shepherd GM, editor. The Synaptic Organization of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 159–204. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neville KR, Haberly LB. Olfactory cortex. In: Shepherd GM, Greer CA, editors. The synaptic organization of the brain. 5. New York: Oxford UP; 2004. pp. 415–454. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertram EH. Temporal lobe epilepsy: where do the seizures really begin? Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14 (Suppl 1):32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thom M, Mathern GW, Cross JH, Bertram EH. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: How do we improve surgical outcome? Ann Neurol. 2010;68:424–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.22142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Traub RD, Wong RK, Miles R, Michelson H. A model of a CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neuron incorporating voltage-clamp data on intrinsic conductances. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:635–50. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.2.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bains JS, Longacher JM, Staley KJ. Reciprocal interactions between CA3 network activity and strength of recurrent collateral synapses. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:720–6. doi: 10.1038/11184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dulla CG, Dobelis P, Pearson T, Frenguelli BG, Staley KJ, Masino SA. Adenosine and ATP link PCO2 to cortical excitability via pH. Neuron. 2005;48:1011–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dulla CG, Frenguelli BG, Staley KJ, Masino SA. Intracellular acidification causes adenosine release during states of hyperexcitability in the hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:1984–93. doi: 10.1152/jn.90695.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hellier JL, Grosshans DR, Coultrap SJ, Jones JP, Dobelis P, Browning MD, Staley KJ. NMDA receptor trafficking at recurrent synapses stabilizes the state of the CA3 network. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2818–26. doi: 10.1152/jn.00346.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miles R, Wong RK. Single neurones can initiate synchronized population discharge in the hippocampus. Nature. 1983;306:371–3. doi: 10.1038/306371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stasheff SF, Bragdon AC, Wilson WA. Induction of epileptiform activity in hippocampal slices by trains of electrical stimuli. Brain Res. 1985;344:296–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90807-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yee AS, Longacher JM, Staley KJ. Convulsant and anticonvulsant effects on spontaneous CA3 population bursts. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:427–41. doi: 10.1152/jn.00594.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hellier JL, Dudek FE. Chemoconvulsant model of chronic spontaneous seizures. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2005;Chapter 9(Unit 9):19. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0919s31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cavazos JE, Das I, Sutula TP. Neuronal loss induced in limbic pathways by kindling: evidence for induction of hippocampal sclerosis by repeated brief seizures. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3106–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03106.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McNamara JO. Kindling: an animal model of complex partial epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1984;16 (Suppl):S72–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loscher W. Animal models of intractable epilepsy. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;53:239–58. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goddard GV, McIntyre DC, Leech CK. A permanent change in brain function resulting from daily electrical stimulation. Exp Neurol. 1969;25:295–330. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(69)90128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–94. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X, Firestein S. The olfactory receptor gene superfamily of the mouse. Nature neuroscience. 2002;5:124–33. doi: 10.1038/nn800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buck LB. Unraveling the sense of smell (Nobel lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:6128–6140. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Axel R. Scents and sensibility: a molecular logic of olfactory perception (Nobel lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:6110–6127. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gire DH, Restrepo D, Sejnowski TJ, Greer C, De Carlos JA, Lopez-Mascaraque L. Temporal processing in the olfactory system: can we see a smell? Neuron. 2013;78:416–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wachowiak M, Shipley MT. Coding and synaptic processing of sensory information in the glomerular layer of the olfactory bulb. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:411–423. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bekkers JM, Suzuki N. Neurons and circuits for odor processing in the piriform cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gottfried JA, Wilson DA. Smell. In: Gottfried JA, editor. Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward. Boca Raton (FL): 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luna VM, Schoppa NE. GABAergic circuits control input-spike coupling in the piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8851–8859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2385-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franks KM, Isaacson JS. Strong single-fiber sensory inputs to olfactory cortex: implications for olfactory coding. Neuron. 2006;49:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luna VM, Pettit DL. Asymmetric rostro-caudal inhibition in the primary olfactory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:533–5. doi: 10.1038/nn.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Igarashi KM, Ieki N, An M, Yamaguchi Y, Nagayama S, Kobayakawa K, Kobayakawa R, Tanifuji M, Sakano H, Chen WR, Mori K. Parallel mitral and tufted cell pathways route distinct odor information to different targets in the olfactory cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7970–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0154-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gire DH, Whitesell JD, Doucette W, Restrepo D. Information for decision-making and stimulus identification is multiplexed in sensory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nn.3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zelano C, Bensafi M, Porter J, Mainland J, Johnson B, Bremner E, Telles C, Khan R, Sobel N. Attentional modulation in human primary olfactory cortex. Nature neuroscience. 2005;8:114–20. doi: 10.1038/nn1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gottfried JA. Central mechanisms of odour object perception. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:628–41. doi: 10.1038/nrn2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Balu R, Pressler RT, Strowbridge BW. Multiple modes of synaptic excitation of olfactory bulb granule cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5621–5632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4630-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyd AM, Sturgill JF, Poo C, Isaacson JS. Cortical feedback control of olfactory bulb circuits. Neuron. 2012;76:1161–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Markopoulos F, Rokni D, Gire DH, Murthy VN. Functional properties of cortical feedback projections to the olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2012;76:1175–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Panuccio G, Sanchez G, Levesque M, Salami P, de Curtis M, Avoli M. On the ictogenic properties of the piriform cortex in vitro. Epilepsia. 2012;53:459–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwabe K, Ebert U, Loscher W. The central piriform cortex: anatomical connections and anticonvulsant effect of GABA elevation in the kindling model. Neuroscience. 2004;126:727–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uva L, Trombin F, Carriero G, Avoli M, de Curtis M. Seizure-like discharges induced by 4-aminopyridine in the olfactory system of the in vitro isolated guinea pig brain. Epilepsia. 2013;54:605–15. doi: 10.1111/epi.12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nguyen MQ, Ryba NJ. A smell that causes seizure. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kass MD, Moberly AH, Rosenthal MC, Guang SA, McGann JP. Odor-specific, olfactory marker protein-mediated sparsening of primary olfactory input to the brain after odor exposure. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6594–602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1442-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnson DM, Illig KR, Behan M, Haberly LB. New features of connectivity in piriform cortex visualized by intracellular injection of pyramidal cells suggest that “primary” olfactory cortex functions like “association” cortex in other sensory systems. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6974–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06974.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]