Abstract

Purpose.

Uveal melanoma (UM) tumors require large doses of radiation therapy (RT) to achieve tumor ablation, which frequently results in damage to adjacent normal tissues, leading to vision-threatening complications. Approximately 50% of UM patients present with activating somatic mutations in the gene encoding for G protein αq-subunit (GNAQ), which lead to constitutive activation of downstream pathways, including protein kinase C (PKC). In this study, we investigated the impact of small-molecule PKC inhibitors bisindolylmaleimide I (BIM) and sotrastaurin (AEB071), combined with ionizing radiation (IR), on survival in melanoma cell lines.

Methods.

Cellular radiosensitivity was determined by using a combination of proliferation, viability, and clonogenic assays. Cell-cycle effects were measured by flow cytometry. Transcriptomic and proteomic profiling were performed by quantitative real-time PCR, reverse-phase protein array analysis, and immunofluorescence.

Results.

We found that the PKC inhibitors combined with IR significantly decreased the viability, proliferation, and clonogenic potential of GNAQmt, but not GNAQwt/BRAFmt cells, compared with IR alone. Combined treatment increased the antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of IR in GNAQmt cells through delayed DNA-damage resolution and enhanced induction of proteins involved in cell-cycle arrest, cell-growth arrest, and apoptosis.

Conclusions.

Our preclinical results suggest that combined modality treatment may allow for reductions in the total RT dose and/or fraction size, which may lead to better functional organ preservation in the treatment of primary GNAQmt UM. These findings suggest future clinical trials combining PKC inhibitors with RT in GNAQmt UM warrant consideration.

Keywords: uveal melanoma, GNAQ mutation, protein kinase C, radiation therapy, radiosensitization

Small-molecule protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors combined with ionizing radiation elicit enhanced antitumor activity against GNAQmt uveal melanoma cells, thus paving the way for genotype-driven rational combinations of PKC inhibitors with radiation therapy in the treatment of uveal melanoma.

Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults.1 Tumors arise from melanocytes within the uveal tract, which is composed of the iris, the ciliary body, and the choroid. The standard treatment for patients with primary UM is organ-preserving radiation therapy (RT), delivered primarily as plaque brachytherapy, proton-beam therapy, or stereotactic external-beam RT.2 However, UM tumors require large doses of radiation per fraction for external-beam RT and high total RT dose (∼80 Gy) to achieve tumor ablation. Large fraction-sizes and high total doses of RT can damage adjacent normal tissue structures of the eye leading to vision-threatening complications, including radiation retinopathy, papillopathy, ischemia, and neovascular glaucoma.3–7

The discovery of BRAF somatic mutations in approximately 60% of cutaneous melanoma patients has led to successful development of targeted therapies that have shown significant clinical benefit resulting in approval by the Food and Drug Administration of two agents: vemurafenib and dabrafenib.8–10 However, BRAF mutations are rare in UM.11 Instead, activating somatic mutations in the GNAQ gene have recently been shown to be present in approximately 50% of UM patients.12 The GNAQ gene encodes for the GTP-binding G-protein αq subunit, which mediates signaling between G-protein–coupled receptors and phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ).13 GNAQ mutations in UM most commonly occur in codon 209 within the GTPase catalytic domain,11 resulting in a loss of intrinsic GTPase activity and constitutive activation of the Gαq protein. This in turn leads to increased activation of PLCβ, which cleaves phosphatidylinositol biphosphate to generate inositol triphosphate and diacylglycerol (DAG). DAG production activates the conventional and novel protein kinase C (PKC) families of proteins, resulting in enhanced growth and apoptotic escape.14 Importantly, recent studies using RNA interference-mediated downregulation of various PKC isoforms have shown that PKCα, PKCβ, PKCε, PKCθ, and PKCδ are functionally important for viability of GNAQmt UM cells (Poulaki V, et al. IOVS 2012;53:ARVO E-Abstract 6871).15,16 Consistent with the important role of PKC signaling in mediating the oncogenic effects of mutant Gαq in UM, the PKC inhibitors enzastaurin, sotrastaurin (AEB071), and bisindolylmaleimide I (BIM) have been demonstrated to exhibit potent antitumor activity against UM cells harboring GNAQ mutations (Poulaki V, et al. IOVS 2012;53:ARVO E-Abstract 6871).15–17

PKC signaling has previously been shown to play a role in mediating cellular responses to ionizing radiation (IR).18–21 The expression of PKCβ increases in a dose-dependent manner within 1 hour after IR exposure.18 Furthermore, the kinase activity of PKC is induced 5-fold within 30 seconds of IR, and PKC-specific downstream nuclear signal transducers are subsequently phosphorylated.22 Inhibition of PKC activity before IR has been demonstrated to attenuate IR-mediated early gene induction, and to impact cell survival in response to IR.19,20 Given the important role of PKC signaling in GNAQmt UM cells, we hypothesized that PKC inhibitors might specifically enhance the sensitivity of GNAQmt cells to IR. We focused here on the radiosensitizing effects of two small-molecule PKC inhibitors, BIM and AEB071, which target PKC isoforms critical for survival of GNAQmt UM cells and exhibit selectivity for PKCs over other kinases (Poulaki V, et al. IOVS 2012;53:ARVO E-Abstract 6871).16,23–27 We report that, compared with the effects of IR alone, the small-molecule PKC inhibitors BIM and AEB071 combined with IR elicit enhanced antitumor activity against GNAQmt, but not GNAQwt/BRAFmt cells, thus paving the way for genotype-driven rational combinations of small-molecule PKC inhibitors with RT in the treatment of GNAQmt UM. Such combinations in the future may lead to improved outcomes and better functional organ preservation.

Methods

Cell Culture

The Mel202 (GNAQQ209L/R210K/BRAFwt) and 92.1 (GNAQQ209L/BRAFwt) UM cell lines were used in this study. The OCM3 (GNAQwt/BRAFV600E) melanoma cell line served as a control. All cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 cell-growth medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin (Pen Strep; Invitrogen). Cells were cultured at 37°C and in 5% CO2. Sanger sequencing verified the genotypes of all cell lines.

Reagents and IR

The small-molecule PKC inhibitor BIM was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and was used at a final concentration of 1 μM. The small-molecule PKC inhibitor AEB071 (Axon Medchem BV, Groningen, The Netherlands) was used at a final concentration of 0.5 μM. Both PKC inhibitors were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and kept at −20°C. Cells were irradiated with a Cs-137 gamma ray irradiator (Gammacell 1000, Springfield, VA, USA) at a dose rate of 7.7 Gy per minute for a total dose of up to 2, 4, or 6 Gy. Zero Gy refers to the sham-irradiated control group. In all experiments, cells were pretreated with PKC inhibitors for 3 hours, followed by IR.20

Cell Viability and Proliferation Assay

Cell viability and cell proliferation were determined 120 hours after IR by using trypan blue exclusion (TC10 automated cell counter; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Statistical differences between treatment groups were evaluated by Student's t-test.

Clonogenic Survival Assay

Radiosensitization was established with the standard clonogenic assay.28 Twenty-four hours after IR, the medium was changed and cells were incubated at 37°C for another 14 days to allow colony formation. At the end of the assay, colonies were fixed and stained with 6% formaldehyde and 0.5% crystal violet. Colonies containing more than 50 cells were counted. Surviving fractions were calculated as (mean colony counts)/([cells inoculated] × [plating efficiency]), in which plating efficiency was defined as (mean colony counts)/(cells inoculated for nonirradiated controls). Statistically significant differences in survival curves were analyzed using the SPSS 19.0 software package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) by means of a weighted, stratified, linear regression, according to the linear-quadratic formula S(D)/S(0) = exp(αD + βD2).28 The sensitivity enhancement ratio (SER) for each PKC inhibitor was calculated as the ratio of surviving fraction of vehicle-treated cells to corresponding PKC inhibitor–treated cells at 6 Gy.

Cell-Cycle Analysis

Cell proliferation (percentage of S-phase cells) and cell-cycle distribution (DNA content) was determined 18 hours after IR using the Click-iT EdU Assay kit (Invitrogen) and TOPRO-3 as a total DNA counterstain (Invitrogen). Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), with a minimum of 20,000 events. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

RNA was extracted from cells 18 hours after IR using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA (SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix; Invitrogen), which was quantified by real-time PCR (StepOne PLUS Real-Time PCR System; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) were used to detect the expression levels of the following genes: CDC25A, CCND1, CDKN1A, CDKN1B, TOP2A, and TP53BP1. Gene expression was normalized to ACTB using the ΔΔCT method. Statistical differences between treatment groups were evaluated by Student's t-test.

Immunofluorescence and Image Analysis

Three and 18 hours after IR, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Amresco, Solon, OH, USA). Nonspecific antibody binding was blocked by 1% bovine serum albumin. Primary antibodies against γH2AX (1:2000; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA) were detected by using anti-rabbit secondary antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen); 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich) was used for nuclei counterstaining.

Cells were imaged using the Cell Lab IC-100 Image Cytometer (IC-100; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), equipped with a ×40/0.90NA objective. The imaging camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) was set to capture 8-bit images at 1 × 1 binning (1344 × 1024 pixels, 6.5 um2/pixel) with two images captured per field (DAPI, AlexaFluor 488). In general, 36 images were captured per coverslip.

Images were analyzed for γH2AX intensity using custom algorithms developed with the Pipeline Pilot (v8.0) software platform (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA) in a similar workflow as previously described.29–31 The background signal was removed from all images using channel-specific correction images, generated by the sum projection of more than 200 randomly selected images for each channel (DAPI, AlexaFluor 488). After background subtraction, nuclear and cell masks were generated using a combination of nonlinear least squares and watershed-from-markers image manipulations of the DAPI images. Cell populations were filtered to discard events with cell aggregates, mitotic cells, apoptotic cells, cellular debris, or poor segmentation. Applied gates were based on nuclear area, nuclear circularity, and cell size/nucleus ratio. All events with nuclear and/or whole-cell masks bordering the edge of the image were additionally eliminated from analysis. Postanalysis measurements were exported to spreadsheet software (Microsoft Excel; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) for further analysis. γH2AX intensity was represented as the sum of pixel intensities in the AlexaFluor 488 channel within the nuclear mask. Responses were normalized to DMSO-treated samples. Statistical differences between treatments were determined by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's correction for multiple comparisons (α < 0 < 1).

Reverse-Phase Protein Array

Eighteen hours after IR, cells were lysed and protein concentration was determined by bicinchonic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein lysates were analyzed by reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) with the assistance of the Functional Proteomics Core Facility (The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA). Heat maps were generated using z-score transformed normalized expression values for each protein with MeV software (Boston, MA, USA).32 Differences in normalized linear expression values for each protein between treatment groups were determined by Student's t-test.

Network analysis was used to identify up- and downregulated biomolecular networks after each treatment condition using NetWalker (Cincinnati, OH, USA).33 For each treatment, protein expression was normalized to vehicle-treated cells. Normalized expression values were used to construct a distribution of edge flux (EF) values. These are unique values assigned to each interaction in the network scoring their relevance to the given dataset based on simultaneous assessment of the data and local network connectivity. The top 30 most up- and downregulated protein-protein interactions based on EF values were used to generate network diagrams. Color scale corresponds to the z-score transformed normalized expression values for each protein presented in the network. Nodes representing proteins not directly measured in the RPPA analysis were excluded from the diagrams.

Western Blotting

The following antibodies were purchased from commercial sources and used for Western blotting: mouse monoclonal p53 (DO-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit polyclonal p21 (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit monoclonal cyclin D1 (92G2; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), and rabbit polyclonal phospho-Chk2 (Thr68; Cell Signaling).

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Protein concentration was determined by bicinchonic acid assay (Pierce). Cell lysates were resolved in NuPAGE 4% to 12% Bis-Tris SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen). After separation, proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked for 1 hour with 5% milk (in tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by SuperSignal West Femto chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce). β-actin (1:4500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as a loading control.

Results

PKC Inhibitors Enhance IR-Induced Reduction in Cell Viability, Cell Proliferation, and Clonogenic Survival of GNAQmt UM Cells

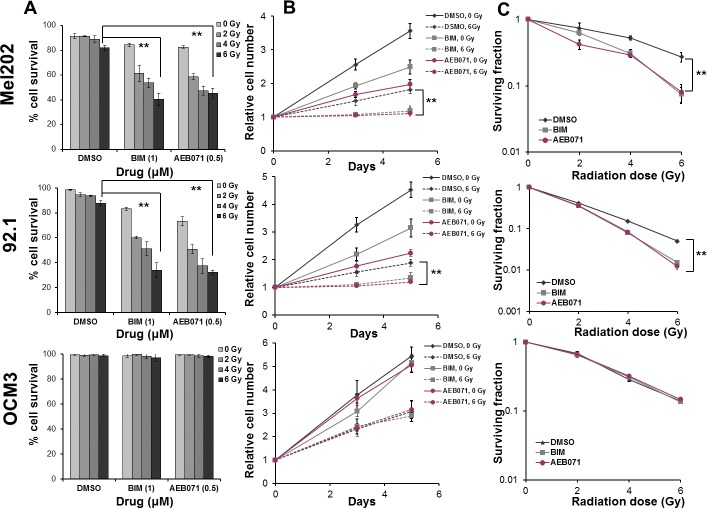

We hypothesized that small-molecule PKC inhibitors used at significantly lower concentrations than their half maximal inhibitory concentration16,24 would enhance IR-induced antitumor activity in UM cells. To test this hypothesis, we compared the impact of treatment with IR alone, PKC inhibitors alone, or PKC inhibitors combined with IR on GNAQmt (Mel202, 92.1) UM cells. GNAQwt/BRAFmt OCM3 cells, an atypical UM cell line more likely derived from a cutaneous melanoma, served as controls. Cells were treated with DMSO, BIM (1 μM) or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0, 2, 4, or 6 Gy of IR. Cell viability and proliferation were determined 120 hours after IR with trypan blue dye, and radiosensitization was established with the standard clonogenic assay.28 Compared with IR alone, both PKC inhibitors combined with IR significantly decreased cell viability (Fig. 1A), cell proliferation (Fig. 1B), and clonogenic survival (Fig. 1C) of GNAQmt, but not GNAQwt/BRAFmt melanoma cells.

Figure 1.

PKC inhibitors enhance IR-induced reduction in cell viability, cell proliferation, and clonogenic survival of GNAQmt UM cells. (A) The GNAQmt (Mel202, 92.1) and GNAQwt (OCM3) cells were treated with DMSO, BIM (1 μM), or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours, followed by 0, 2, 4, or 6 Gy of IR. Cell viability was determined 120 hours after IR by using trypan blue dye. (B) Cells were treated with DMSO, BIM (1 μM), or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0 or 6 Gy of IR. Cell proliferation was determined 72 hours and 120 hours after IR by using trypan blue dye. (C) Cells were treated with DMSO, BIM (1 μM), or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0, 2, 4, or 6 Gy of IR. Twenty-four hours after IR, the medium was changed and cells were incubated at 37°C for another 14 days to allow colony formation. The cultures were stained and colonies containing more than 50 cells were counted. Bars represent mean ± SD from three biological replicates; **P < 0.001 for comparing IR only to PKC inhibitor combined with IR at 6 Gy.

Cell viability (Fig. 1A) was not largely affected by IR alone. Compared with IR or PKC inhibitor monotherapy, combination therapy demonstrated a further significant and IR dose-dependent reduction in viability of GNAQmt cells. The viability of GNAQwt/BRAFmt melanoma cells was not affected by PKC inhibitors or by combination therapy.

Cell proliferation (Fig. 1B) was significantly decreased by IR alone in both GNAQmt and GNAQwt/BRAFmt cells. Compared with IR or PKC inhibitor monotherapy, combination therapy demonstrated a further significant reduction in proliferation of GNAQmt cells. The proliferation of GNAQwt/BRAFmt melanoma cells was not affected by PKC inhibitors.

Combination therapy significantly reduced the clonogenic survival of GNAQmt, but not GNAQwt/BRAFmt melanoma cells (Fig. 1C). Radiosensitization was statistically determined by measuring the SER, defined as the ratio of surviving fraction of vehicle-treated cells to corresponding PKC inhibitor–treated cells at 6 Gy. GNAQmt Mel202 cells exhibited a SER of 4.07 and 3.75 for BIM and AEB071, respectively. GNAQmt 92.1 cells showed a similar effect with SER of 2.64 for BIM and 3.16 for AEB071. SER ranged from 0.98 for AEB071 to 1.01 for BIM in GNAQwt/BRAFmt OCM3 cells, indicating no radiosensitizing effect by PKC inhibitors in GNAQwt/BRAFmt cells. Thus, our results suggest PKC inhibitors increase radiosensitivity in GNAQmt UM cell lines. As AEB071 is currently being evaluated in phase I clinical trials for metastatic UM, we focused further studies on the effects of AEB071.

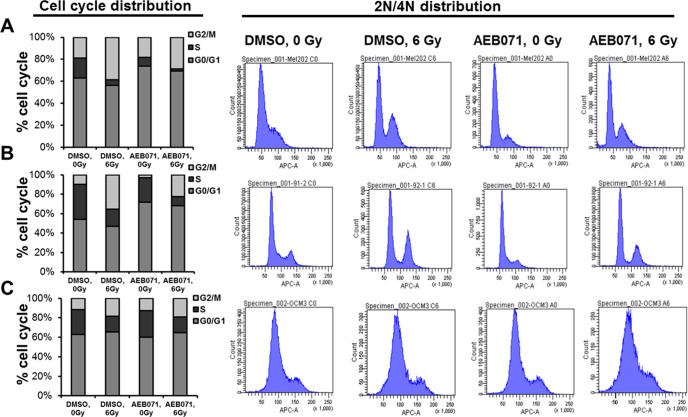

PKC Inhibitor AEB071 Increases IR-Induced Cell Cycle Arrest in GNAQmt UM Cells

We next examined the effect of combining PKC inhibitors with IR on cell-cycle distribution in GNAQmt (Mel202, 92.1) and GNAQwt/BRAFmt (OCM3) cells. Cells were treated with DMSO or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0 or 6 Gy of IR. Cell-cycle distribution was determined 18 hours after IR by flow cytometry. Compared with IR alone, AEB071 combined with IR decreased the proportion of proliferating cells (S-phase) in GNAQmt, but not GNAQwt/BRAFmt melanoma cells (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

PKC inhibitor AEB071 increases IR-induced cell-cycle arrest in GNAQmt UM cells. (A) GNAQmt Mel202, (B) GNAQmt 92.1, and (C) GNAQwt OCM3 cells were treated with DMSO or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0 or 6 Gy of IR. Eighteen hours after IR, cell-cycle distribution, including percentage of S-phase cells (left) and 2N/4N DNA content (right), were detected by flow cytometry.

IR alone decreased the proportion of GNAQmt and GNAQwt/BRAFmt cells in S phase, and increased the proportion of GNAQmt and GNAQwt/BRAFmt cells in G2/M phases (Fig. 2). AEB071 alone decreased the proportion of GNAQmt cells in S phase, and increased the proportion of GNAQmt cells in G1 phase (Figs. 2A, 2B). Combination therapy demonstrated the greatest decrease in the proportion of proliferating cells (S-phase) in GNAQmt cell lines. The cell-cycle distribution in GNAQwt/BRAFmt cells was not affected by AEB071 (Fig. 2C). These experiments suggest that the impacts observed on proliferation and clonogenicity (Fig. 1) were mediated in part by the combined effects of PKC inhibition and IR on cell-cycle progression.

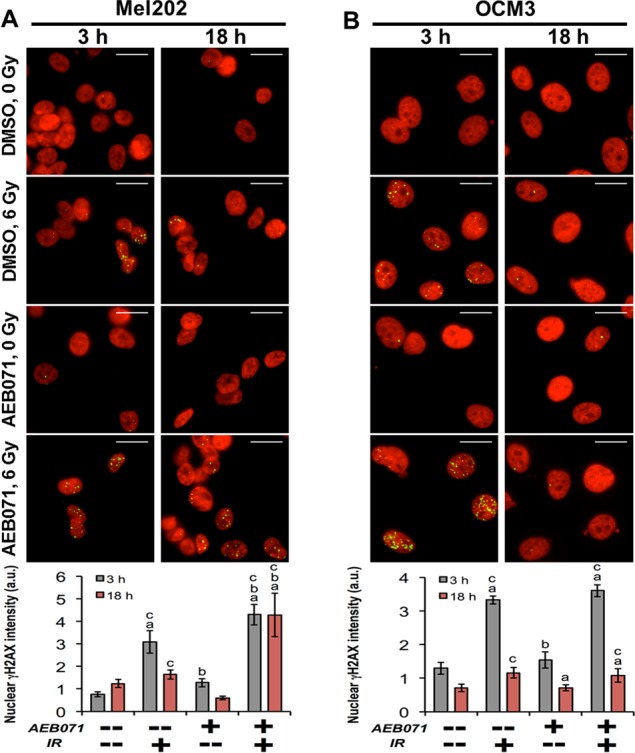

PKC Inhibitor AEB071 Augments IR-Induced DNA Damage–Associated γH2AX Staining Intensity in GNAQmt UM Cells

To investigate the impact of AEB071 and IR on the DNA damage response, we used high-throughput microscopy and automated image analysis to measure induction and resolution of the phosphorylated histone protein H2AX (γH2AX) in GNAQmt Mel202 and GNAQwt/BRAFmt OCM3 cells. γH2AX is directed to sites flanking DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) during the DNA damage response. As such, γH2AX protein expression is a sensitive indicator of IR-induced DNA DSBs.34 In these experiments, γH2AX intensity (sum of pixel intensity in the nucleus) was analyzed by customized image analysis tools,29–31 which automatically identify cells and nuclei to extract fluorescence-based measurements. In Mel202 cells (Fig. 3A), IR increased γH2AX intensity by 3.1-fold 3 hours after treatment. Combined IR and AEB071 treatment further increased γH2AX intensity by 40% relative to IR alone (4.3-fold relative to DMSO controls). Eighteen hours after IR, levels of γH2AX in cells subjected to IR alone decreased by 47% compared with 3-hour levels, whereas the levels of γH2AX in cells subjected to combined treatment were unchanged from 3-hour levels. In GNAQwt/BRAFmt OCM3 cells, levels of γH2AX did not differ significantly between cells subjected to IR alone (3.3-fold) or combined treatment (3.6-fold; Fig. 3B). Eighteen hours after IR, levels of γH2AX declined by 67% compared with 3-hour levels in both groups. These findings suggest that the PKC inhibitor AEB071 delays resolution of IR-induced DNA DSBs in GNAQmt Mel202 cells.

Figure 3.

The PKC inhibitor AEB071 augments IR-induced DNA damage-associated γH2AX staining intensity in GNAQmt UM cells. (A) GNAQmt Mel202 and (B) GNAQwt OCM3 cells were treated with DMSO or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0 or 6 Gy of IR. Three and 18 hours after IR, cells were fixed, stained with anti-γH2AX antibody, and examined by high-throughput microscopy (upper). DAPI (nucleus) and γH2AX were pseudo-colored in red and green, respectively. Binary nuclear and cellular masks were generated by a combination of watershed and threshold image transformations. The γH2AX sum of pixel intensities within nuclear masks was used to quantify γH2AX staining intensity (lower). Values are normalized to DMSO controls at each time point. Error bars indicate SEM (n > 50 cells/condition collected over two independent experiments). Scale bar: 20 μm; a indicates statistically different from DMSO control; b indicates statistically different from IR alone; and c indicates statistically different from AEB071 alone.

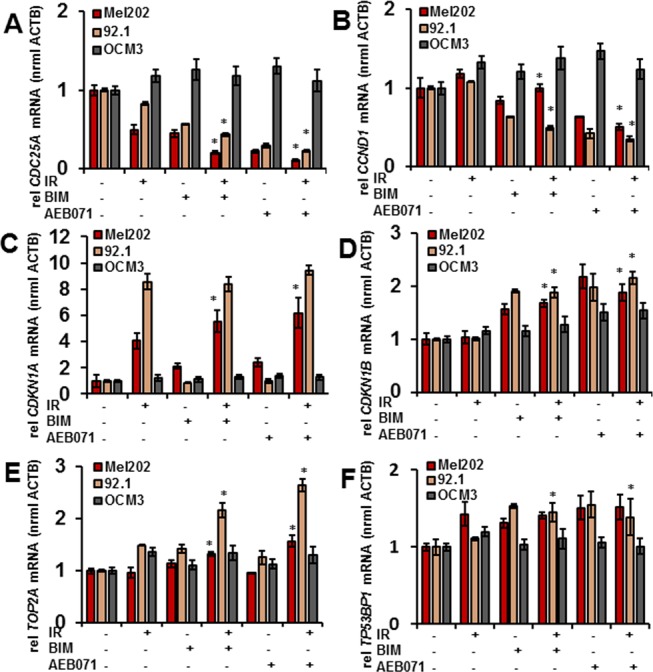

PKC Inhibitors Enhance IR-Induced Gene Expression Changes Affecting Cell Cycle and DNA Damage Repair in GNAQmt UM Cells

We next sought to characterize changes in the expression of genes associated with cell-cycle progression and DNA damage in response to combination therapy in GNAQmt (Mel202, 92.1) and GNAQwt/BRAFmt (OCM3) cells. Cells were treated with DMSO, BIM (1 μM), or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0 or 6 Gy of IR. RNA was isolated 18 hours after IR, and mRNA expression was measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Compared with IR alone, combination therapy in GNAQmt cells significantly reduced the expression of positive regulators of cell-cycle progression, including CDC25A (Fig. 4A) and CCND1 (Fig. 4B), and significantly increased the expression of negative regulators of cell-cycle progression, including CDKN1A (Fig. 4C) and CDKN1B (Fig. 4D). The expression of genes implicated in DNA damage response, including TOP2A (Fig. 4E) and TP53BP1 (Fig. 4F), was also significantly increased after combined treatment compared with IR alone, except in Mel202 cells where a similar increase in the expression level of TP53BP1 after IR alone and after combined treatment was observed. Conversely, the expression of these genes in GNAQwt/BRAFmt melanoma cells was not largely affected by PKC inhibitors or by combination therapy compared with IR alone.

Figure 4.

PKC inhibitors enhance IR-induced gene expression changes in GNAQmt UM cells. The GNAQmt (Mel202, 92.1) and GNAQwt (OCM3) cells were treated with DMSO, BIM (1 μM), or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0 or 6 Gy of IR. RNA was isolated 18 hours after IR, and mRNA expression was measured for the following genes by quantitative real-time PCR: (A) CDC25A, (B) CCND1, (C) CDKN1A, (D) CDKN1B, (E) TOP2A, (F) TP53BP1. Bars represent mean ± SD from three biological replicates; *P < 0.05 for comparing IR only to PKC inhibitor combined with IR at 6 Gy.

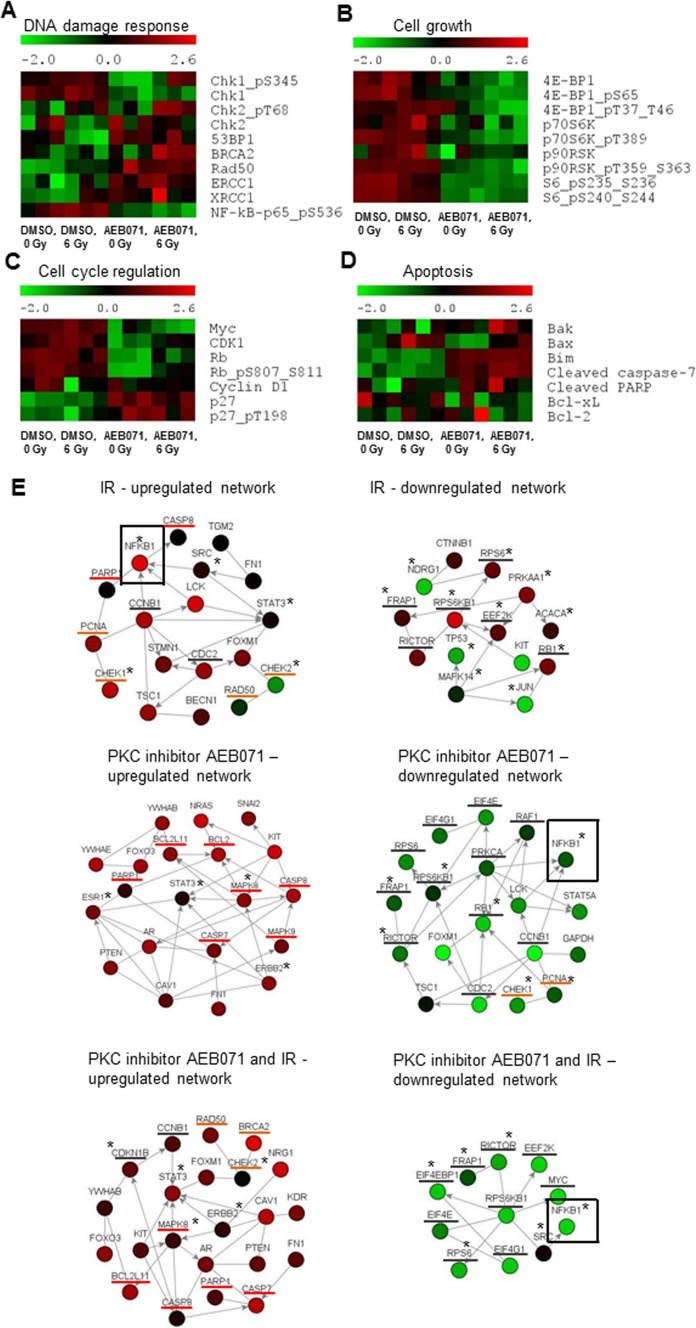

PKC Inhibitor AEB071 Modulates IR-Induced Changes in Protein Expression and Posttranslational Modification in GNAQmt UM Cells

To characterize the impact of combination therapy on proteins involved in DNA damage response, cell-cycle progression, and cell survival, we performed proteomic profiling by RPPA analysis in GNAQmt Mel202 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). Cells were treated with DMSO or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0 or 6 Gy of IR. When analyzing proteins involved in the DNA damage response at 18 hours after 0 or 6 Gy of IR exposure (Fig. 5A), we found significant increases in Rad50 expression and increased nuclear factor (NF)-κB phosphorylation after IR alone. Treatment with PKC inhibitor alone resulted in significantly increased expression of Rad50, ERCC1, and XRCC1, and significantly decreased phosphorylation of NF-κB. Compared with individual treatments, combined treatment with AEB071 and IR resulted in significantly increased Chk2 phosphorylation at threonine 68 and increased expression levels of 53BP1, BRCA2, Rad50, and total Chk2. Additionally, combined treatment resulted in significantly decreased phosphorylation of NF-κB. These data suggest persistent DNA damage signaling after combination therapy. Among the proteins involved in cell-cycle progression (Fig. 5C), AEB071 treatment alone resulted in significantly increased total levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27; decreased phosphorylation of Rb; and decreased levels of total Rb, Myc, and CDK1. These effects persisted in the presence of IR, indicating cell-cycle arrest on combined treatment. Among proteins involved in cell growth (Fig. 5B), the phosphorylation of 4EBP1 and S6 was significantly decreased after IR alone and PKC inhibitor alone. AEB071 alone also significantly decreased the expression of p70S6K and p90RSK. Compared with individual treatments, combination therapy significantly decreased the phosphorylation of 4EBP1, p70S6K, p90RSK, and S6, as well as the expression level of 4E-BP1 and p70S6K, implying cell growth arrest after combined treatment. When analyzing proteins involved in apoptosis (Fig. 5D), we detected significantly increased expression of Bax after IR alone. AEB071 treatment alone resulted in significantly increased cleaved caspase-7 and the expression of Bim. Compared with individual treatments, combination therapy significantly increased caspase-7 cleavage, and Bim and Bax expression, suggesting enhanced apoptotic signaling after combination therapy.

Figure 5.

PKC inhibitor AEB071 modulates IR-induced changes in protein expression and posttranslational modification in GNAQmt UM cells. GNAQmt Mel202 cells were treated with DMSO or AEB071 (0.5 μM) for 3 hours followed by 0 or 6 Gy of IR. Cell lysates were collected 18 hours after IR, and the expressions of proteins were determined by RPPA. Heat maps represent normalized expression values for each protein (red, high; green, low). Each treatment was done in triplicate, which corresponds to three distinct heat map boxes per treatment condition. Effects on the expression of select proteins controlling (A) DNA damage response, (B) cell growth, (C) cell-cycle regulation, and (D) apoptosis are presented. (E) Network analysis was performed to identify the most represented signaling networks on each treatment condition using NetWalker software. The top 30 most up- and downregulated protein-protein interactions based on EF values were used to generate network diagrams. Color scale corresponds to the z-score transformed normalized expression values for each protein presented in the network. Nodes, proteins; edges, network interactions between proteins; asterisks, phosphorylated proteins; underlined in red, proteins involved in apoptosis; underlined in orange, proteins involved in the DNA damage response; underlined in grey, proteins involved in cell-cycle progression and cell growth.

To determine the signaling networks most affected in each treatment condition based on the whole RPPA dataset, we performed network analysis (Fig. 5E). NetWalker33 is an algorithm that simultaneously integrates RPPA signal distribution with local network connectivity and prioritizes biomolecular networks most active in the experimental data. Figure 5E shows the highest-scoring up- and downregulated networks after IR alone, PKC inhibitor alone, and after combined treatment. In the IR-alone group, among the highest-scoring interactants in the upregulated group was NF-kB pS536. Conversely, in the PKC-treated groups (alone and combined with IR), NF-kB pS536 was among the most downregulated interactants, potentially providing a mechanistic clue into the radiosensitizing properties of the PKC inhibitor AEB071. Additionally, compared with IR alone, the upregulated network after combined treatment preserved proteins involved in the DNA damage response, and gained proapoptotic factors and inhibitors of the cell-cycle progression. Conversely, the downregulated network after combined treatment consisted of the NF-κB pathway and mediators of cell growth. These data establish a reciprocal dynamic between the PKC inhibitor and IR, wherein separate as well as common mechanisms of cell survival are inhibited by the combined therapy. Additional validation of protein expression levels of select proteins by immunoblot analysis supported our gene expression and RPPA results (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Discussion

RT is the standard treatment for patients with primary UM. However, the large doses of RT required to achieve tumor control can affect normal tissues adjacent to the tumor and often lead to vision-threatening complications, including radiation retinopathy, papillopathy, ischemia, and neovascular glaucoma.3–7 The most frequently observed radiation complication is radiation retinopathy, which has been described in up to 50% of patients treated with RT.35–37 Unfortunately, the options for management of radiation retinopathy and other common radiation-related complications remain limited.37 Therefore, there is an unmet clinical need for therapeutic agents capable of selectively enhancing the sensitivity of UM cells to radiation. Such agents would potentially allow for reductions in the total dose and/or fraction size of RT delivered to the eye, and would represent an important clinical advance by minimizing the frequency of radiation-induced vision impairment.

In this study, we investigated the radiosensitizing effects of the small-molecule PKC inhibitors BIM and AEB071 in UM cell lines expressing mutant GNAQ. Melanoma cells harboring wild-type GNAQ served as controls. We found that, compared with IR or PKC inhibitors alone, combined treatment resulted in significantly enhanced antitumor activity against GNAQmt, but not GNAQwt/BRAFmt cells, evidenced by decreased cell viability, decreased cell proliferation, and decreased clonogenic survival. Consistent with these observations, combination therapy resulted in the highest reduction in the S-phase fraction of GNAQmt cells. Together, these results demonstrate that small-molecule PKC inhibitors specifically enhance the effect of IR in GNAQmt cells, highlighting a unique vulnerability in this class of tumors.

To determine the molecular mechanisms underlying the reduced clonogenic potential of GNAQmt UM cells on the combined treatment, we measured the induction and resolution of γH2AX foci, a surrogate marker of DNA DSBs. Based on nuclear γH2AX intensity, DNA DSBs were induced to a greater extent and persisted longer in GNAQmt cells treated with combination therapy compared with IR alone. Conversely, PKC inhibition did not affect γH2AX intensity or dynamics in GNAQwt/BRAFmt melanoma cells. This finding suggests that combination therapy may render GNAQmt tumors more susceptible to the effects of DNA DSBs by delaying DNA damage resolution. Consistent with these observations, GNAQmt cells treated with combination therapy showed persistently increased Chk2 phosphorylation and increased levels of other DNA damage–associated proteins, such as BRCA2, Rad50, and 53BP1, 18 hours after IR, a time at which these proteins had returned to baseline in cells treated with IR alone, suggesting completed repair processes. In sum, these data indicate that PKC inhibitors are able to potentiate IR-induced DNA damage and interfere with the rate of DNA repair in GNAQmt cells. This mechanism is common among potent radiosensitizers.34

Our results also demonstrate that small-molecule PKC inhibitors combined with IR collaborate to promote antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of IR in GNAQmt cells through induction of proteins involved in cell-cycle arrest, cell-growth arrest, and apoptosis. Activating phosphorylation of NF-κB on serine 536 was central to the upregulated network after IR alone, suggesting NF-κB activation is an important mechanism of resistance to IR in UM cells.38 Consistent with previous findings, however, there was a marked decrease in NF-κB pS536 protein level in GNAQmt cells treated with PKC inhibitor alone.16 Importantly, combining the PKC inhibitor AEB071 with IR blocked the activating phosphorylation of NF-kB on serine 536, suggesting that one potential mechanism by which combination therapy sensitizes GNAQmt tumors to IR treatment is through attenuation of the NF-κB mediated stress response. Suppression of NF-κB activity has previously been shown to potentiate radiosensitizing activity in lymphoma, prostate, cervical, glioblastoma, and colorectal cell lines,39 further supporting NF-κB inhibition as a mechanism behind PKC inhibitor–mediated radiosensitization of GNAQmt UM cells.

Our study is subject to several limitations. The results are limited to two GNAQmt UM cell lines, which harbor the same GNAQ Q209 mutation. This mutation site is, however, the most common mutation present in patients with primary UM (∼45%), whereas mutations affecting the GNAQ R183 position are much less frequent (∼3%).12 Apart from GNAQ Q209 and R183 mutations, UM patients also harbor mutations in GNA11 gene, which codes for the Gα11 subunit of the GTP-binding G-protein.40 GNA11 mutations affect the same codon positions as GNAQ mutations, Q209 and R183, but are less frequent, present in approximately 30% and approximately 2% of patients with primary UM, respectively.40 The close functional relationship between Gαq and Gα11, together with constitutive activation of PKCs in both GNAQmt and GNA11mt UM cells, provides rationale that UM cells harboring GNAQ or GNA11 mutations are selectively sensitive to PKC inhibitors. This has indeed been demonstrated in several previous studies (Poulaki V, et al. IOVS 2012;53:ARVO E-Abstract 6871).15–17 Recent work by Chen et al.,17 using two different PKC inhibitors across a panel of six different UM cell lines harboring GNAQ or GNA11 mutations, as well as melanocyte cell lines stably overexpressing GNAQ or GNA11, demonstrated selective growth inhibition of these cells, whereas melanoma cell lines harboring mutations in other genes were not sensitive to PKC inhibition, regardless of whether they were derived from uveal or cutaneous melanoma. Although PKC inhibition causes selective growth inhibition in both cells carrying an activating GNAQ or GNA11 mutation, whether the combination of PKC inhibitors with IR will result in the same radiosensitization in cells harboring GNA11 (and GNAQ R183) mutations requires experimental validation. As our control GNAQwt/BRAFmt OCM3 cell line was recently identified as an atypical UM cell line more likely derived from a cutaneous melanoma,11 we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed cooperative effects of PKC inhibitors and IR are relevant to all UM cells, and not restricted to UM cells carrying GNAQ mutations. However, this possibility would not obviate the potential therapeutic benefit of combination therapy in patients with UM.

The results of previous attempts to specifically radiosensitize UM tumors to radiation have been limited in success. Intravitreal injections of VEGF pathway inhibitors (e.g., bevacizumab, ranibizumab, pegaptanib sodium) have recently been tested for radiosensitizing effects in the treatment of primary UM; however, they have yielded inconsistent results.41,42 These studies did, however, demonstrate the feasibility of combining drugs delivered intravitreally with RT. The preclinical data presented in this study support the hypothesis that PKC small-molecule inhibitors should be considered as part of a combined modality approach with RT in the treatment of primary GNAQmt UM. As phase I clinical trials of the small-molecule PKC inhibitor AEB071 are ongoing in metastatic UM, a clinical trial using PKC inhibitors in combination with RT in primary GNAQmt UM is warranted. This approach would represent an important advance in genotype-driven personalized targeted therapy and promises to potentially improve patient outcome while minimizing vision-threatening toxicities associated with RT.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the joint participation by the Adrienne Helis Malvin Medical Research Foundation and the Diana Helis Henry Medical Research Foundation through their direct engagement in the continuous active conduct of medical research in conjunction with Baylor College of Medicine.

SEM is a Dan L. Duncan Scholar, a Caroline Wiess Law Scholar, and a member of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center (supported by the National Cancer Institute [NCI] Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA125123) at Baylor College of Medicine. Additional support was provided by K01 DK096093 (SMH), and the Pilot/Feasibility Program of the Diabetes Research Center (P30-DK079638) at Baylor College of Medicine (SMH). NM is a Dan L. Duncan Scholar, a Caroline Wiess Law Scholar, and a member of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center (supported by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA125123) at Baylor College of Medicine. His work is also supported by the Conquer Cancer Foundation of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Career Development Award, a Pilot/Feasibility Program of the Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center (P30-DK079638) at Baylor College of Medicine, and by the Prostate Cancer Foundation. Imaging resources were supported by Specialized Cooperative Centers Program for Reproductive Research U54 HD-007495 (FJ DeMayo), P30 DK-56338 (MK Estes), P30 CA-125123 (CK Osborne); and the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center of Baylor College of Medicine. Supported by the Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core at Baylor College of Medicine with funding from the National Institutes of Health (AI036211, CA125123, and RR024574) and the expert assistance of Joel M. Sederstrom.

Disclosure: J.Z. Cerne, None; S.M. Hartig, None; M.P. Hamilton, None; S.A. Chew, None; N. Mitsiades, None; V. Poulaki, None; S.E. McGuire, None

References

- 1. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012; 62: 10–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seregard S, Pelayes DE, Singh AD. Radiation therapy: uveal tumors. Dev Ophthalmol. 2013; 52: 36–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Char DH, Kroll SM, Castro J. Long-term follow-up after uveal melanoma charged particle therapy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1997; 95: 171–187 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shields CL, Shields JA, Cater J, et al. Plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma: long-term visual outcome in 1106 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118: 1219–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nasser QJ, Gombos DS, Williams MD, et al. Management of radiation-induced severe anophthalmic socket contracture in patients with uveal melanoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012; 28: 208–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groenewald C, Konstantinidis L, Damato B. Effects of radiotherapy on uveal melanomas and adjacent tissues. Eye. 2012; 27: 163–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang MY, McCannel TA. Local treatment failure after globe-conserving therapy for choroidal melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013; 97: 804–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363: 809–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 707–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 1694–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Griewank KG, Yu X, Khalili J, et al. Genetic and molecular characterization of uveal melanoma cell lines. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012; 25: 182–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature. 2009; 457: 599–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hubbard KB, Hepler JR. Cell signaling diversity of the Gqα family of heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell Signal. 2006; 18: 135–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blobe GC, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Regulation of protein kinase C and role in cancer biology. Cancer Met Rev. 1994; 13: 724–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu X, Zhu M, Fletcher JA, Giobbie-Hurder A, Hodi FS. The protein kinase C inhibitor enazastaurin exhibits antitumor activity against uveal melanoma. PloS One. 2012; 7: e29622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu X, Li J, Zhu M, Fletcher JA, Hodi FS. Protein kinase C inhibitor AEB071 targets ocular melanoma harboring GNAQ mutation via effects on the PKC/Erk1/2 and PKC/NF-κB pathways. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012; 11: 1905–1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen X, Wu Q, Tan L, et al. Combined PKC and MEK inhibition in uveal melanoma with GNAQ and GNA11 mutations [published online ahead of print October 21, 2013]. Oncogene. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Woloschak GE, Chang-Liu CM, Shearin-Jones P. Regulation of protein kinase C by ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1990; 50: 3963–3967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hallahan DE, Sukhatme VP, Sherman ML, Virudachalam S, Kufe D, Weichselbaum RR. Protein kinase C mediates x-ray inducibility of nuclear signal transducers EGR1 and JUN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991; 88: 2156–2160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hallahan DE, Virudachalam S, Schwartz JL, Panje N, Mustafi R, Weichselbaum RR. Inhibition of protein kinases sensitizes human tumor cells to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 1992; 129: 345–350 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bluwstein A, Kumar N, Leger K, et al. PKC signaling prevents irradiation-induced apoptosis of primary human fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 2013; 4: e498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hallahan DE, Virudachalam S, Sherman ML, Huberman E, Kufe DW, Weichselbaum RR. Tumor necrosis factor gene expression is mediated by protein kinase C following activation by ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1991; 51: 4565–4569 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mackay HJ, Twelves CJ. Targeting the protein kinase C family: are we there yet? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007; 7: 554–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilkinson SE, Parker PJ, Nixon JS. Isoenzyme specificity of bisindolylmaleimides, selective inhibitors of protein kinase C. Biochem J. 1993; 294: 335–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Serova M, Ghoul A, Benhadji KA, et al. Preclinical and clinical development of novel agents that target the protein kinase C family. Semin Oncol. 2006; 33: 466–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Skvara H, Dawid M, Kleyn E, et al. The PKC inhibitor AEB071 may be a therapeutic option for psoriasis. J Clin Invest. 2008; 118: 3151–3159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wagner J, von Matt P, Sedrani R, et al. Discovery of 3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-4-[2-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)quinazolin-4-yl]-pyrrole-2,5-dione (AEB071), a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C isotypes. J Med Chem. 2009; 52: 6193–6196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Franken NAP, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2006; 1: 2315–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hartig SM, Newberg JY, Bolt MJ, Szafran AT, Marcelli M, Mancini MA. Automated microscopy and image analysis for androgen receptor function. Methods Mol Biol. 2011; 776: 313–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hartig SM, He B, Newberg JY, et al. Feed-forward inhibition of androgen receptor activity by glucocorticoid action in human adipocytes. Chem Biol. 2012; 19: 1126–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Szafran AT, Szwarc M, Marcelli M, Mancini MA. Androgen receptor functional analyses by high throughput imaging: determination of ligand, cell cycle, and mutation-specific effects. PLoS One. 2008; 3: e3605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saeed AI, Bhagabati NK, Braisted JC, et al. TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 2006; 411: 134–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Komurov K, Dursun S, Erdin S, Ram PT. NetWalker: a contextual network analysis tool for functional genomics. BMC Genomics. 2012; 13: 282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Citrin D, Camphausen K, Curran W, Dicker AP. Evaluation of novel agents as radiosensitizers from laboratory to clinic. ASCO Educational Book. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stack R, Elder M, Abdelaal A, Hidajat R, Clemett R. New Zealand experience of I125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2005; 33: 490–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jensen AW, Petersen IA, Kline RW, Stafford SL, Schomberg PJ, Robertson DM. Radiation complications and tumor control after 125I plaque brachytherapy for ocular melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005; 63: 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones R, Gore E, Mieler W, et al. Posttreatment visual acuity in patients treated with episcleral plaque therapy for choroidal melanomas: dose and dose rate effects. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002; 52: 989–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ahmed KM, Li JJ. NF-kappa B-mediated adaptive resistance to ionizing radiation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008; 44: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Magne N, Toillon RA, Bottero V, et al. NF-κB modulation and ionizing radiation: mechanisms and future directions for cancer treatment. Cancer Lett. 2006; 231: 158–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, et al. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363: 2191–2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. el Filali M, Ly LV, Luyten GP, et al. Bevacizumab and intraocular tumors: an intriguing paradox. Mol Vis. 2012; 18: 2454–2467 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sudaka A, Susini A, Lo Nigro C, et al. Combination of bevacizumab and irradiation on uveal melanoma: an in vitro and in vivo preclinical study. Invest New Drugs. 2013; 31: 59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]