Abstract

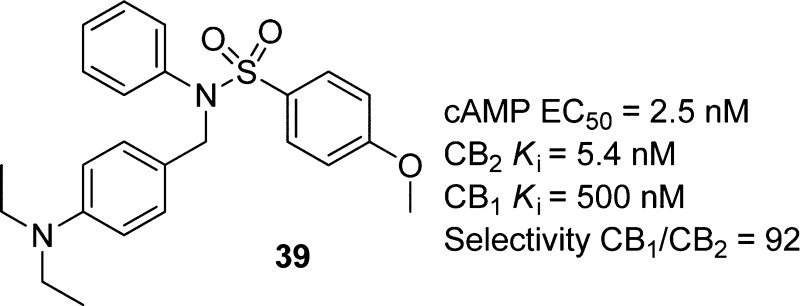

An extensive exploration of the structure–activity relationship of a trisubstituted sulfonamide series led to the identification of 39, which is a potent and selective CB2 receptor inverse agonist [Ki(CB2) = 5.4 nM, and Ki(CB1) = 500 nM]. The functional properties measured by cAMP assays indicated that the selected compounds were CB2 inverse agonists with high potency values (for 34, EC50 = 8.2 nM, and for 39, EC50 = 2.5 nM). Furthermore, an osteoclastogenesis bioassay indicated that trisubstituted sulfonamide compounds showed great inhibition of osteoclast formation.

Keywords: Cannabinoid receptors, inverse agonists, trisubstituted sulfonamides, osteoclast inhibitors

Cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2, respectively) were identified in the early 1990s as members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily.1,55 While CB1 receptors are primarily found in the central nervous system (CNS), CB2 receptors are predominantly located in tissues and cells of the immune system, such as tonsils, spleen, macrophages, and lymphocytes.2 Also, there is some evidence of the presence of the CB2 receptor in the CNS.3,66

Recently, numerous agonists and antagonists of cannabinoid receptors have been explored because of the important role of the endocannabinoid system in various diseases and disorders.4 Among these, CB1 receptor ligands have been developed for pain, appetite stimulation, nausea, neurodegeneration, hypermotility, and inflammation.5 However, the CB1 receptor ligands are known to cause side effects in the CNS such as cognitive dysfunction, motor incoordination, and sedation.6 Because of differences in receptor distribution and signal transduction mechanisms, CB2-selective ligands are considered as medications without CNS side effects,7 and such ligands are being actively investigated for use in a multitude of diseases and pathological conditions,8 such as atherosclerosis,9 myocardial infarction,10 stroke,11 gastrointestinal inflammatory,12 autoimmune,13 and neurodegenerative14 disorders, bone disorders,15−88 and cancer.16

The development of CB2 receptor-selective ligands has attracted significant attention because of the therapeutic potential of CB2 receptor modulation.17−33 The first CB2 inverse agonist is SR144528, which is extensively used as the standard to measure the specificity of various cannabinoid inverse agonists for CB2 in animal models.18 Other notable examples of CB2 receptor agonists and antagonists include AM630,19 JTE-907,20 Sch225336,21 and JWH-133.22 Recently, on the basis of the research in three-dimensional CB2 receptor structure model23,56 and pharmacophore database searches, our group also reported the discovery of novel bis-amide derivatives [1 (Figure 1)] as CB2 receptor inverse agonists and osteoclast inhibitors.24 However, the optimization of bis-amide derivatives is limited by the synthesis method and symmetrical scaffold.

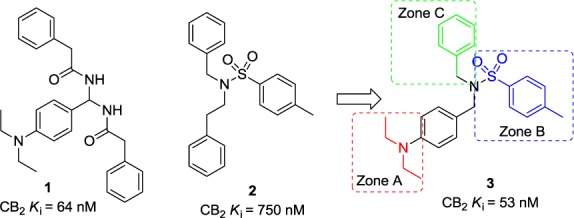

Figure 1.

Structures of CB2 receptor inverse agonists and new scaffold discovery.

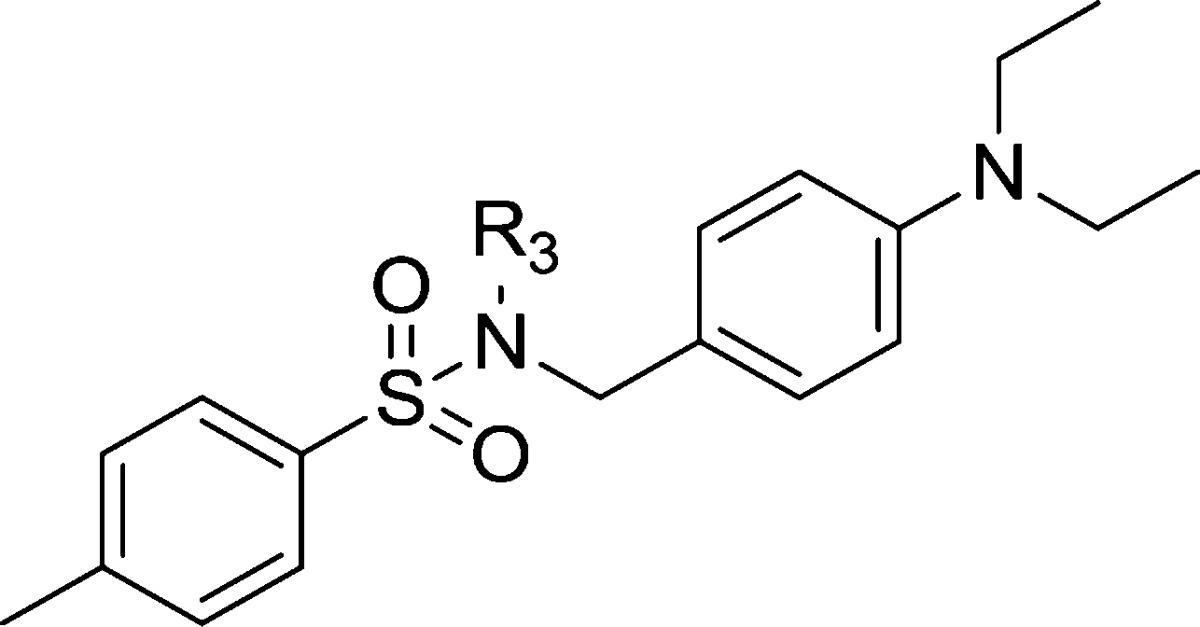

On the basis of continuing virtual screening and QSAR results,25 we designed and synthesized 2, with a trisubstituted sulfonamide scaffold, as a novel chemotype with CB2 binding activity [Ki(CB2) = 750 nM]. Compared with the structure of 1 and considering the QSAR results, we believed that a longer chain in zone A was important for the CB2 inverse agonist (Figure 1). Compound 3 with a diethylamino group was synthesized and confirmed to have a better CB2 binding affinity [Ki(CB2) = 53 nM] and a good CB2 selectivity index [SI = 43, calculated as the Ki(CB1)/Ki(CB2) ratio]. Given this promising result, 3 was chosen as a prototype for further structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. Herein, we reported the design and synthesis of novel trisubstituted sulfonamide derivatives as CB2 inverse agonists. Binding activities were investigated to define their SAR and ligand functionality. After we modified the groups at zones A–C, some derivatives, such as 34 [Ki(CB2) = 5.5 nM, and SI = 15], 39 [Ki(CB2) = 5.4 nM, and SI = 92], and 45 [Ki(CB2) = 4.0 nM, and SI = 120], were identified as CB2-selective ligands with improved CB2 binding affinity and high selectivity. These compounds were selected for the functional property investigation by a cAMP assay, which showed their high potency (for 34, EC50 = 8.2 nM, and for 39, EC50 = 2.5 nM) as CB2 inverse agonists. Moreover, these compounds also showed great inhibition activity with osteoclast cells.

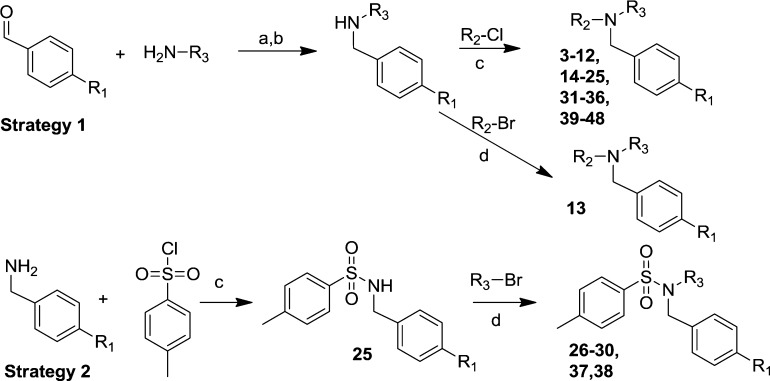

The trisubstituted sulfonamide derivatives were synthesized by two general strategies (Scheme 1). In the first strategy, the different imine intermediates, synthesized from reductive amination reactions of substituted aryl aldehydes and various amines, were reacted with different sulfonyl chlorides to prepare compounds 3–12, 14–25, 31–36, and 39–48, as well as with benzyl bromide to obtain 13. Compounds 26–30, 37, and 38 were obtained by the reaction of intermediate 25 with various bromides. The structures of all the compounds were characterized by 1H NMR and ESI-HRMS spectra; purity was confirmed by HPLC.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Trisubstituted Sulfonamides.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CH3OH, reflux; (b) CH3OH, NaBH4; (c) Et3N, CH2Cl2; (d) K2CO3, CH3COCH3, reflux.

Biological data of compounds with different substituents of zone A are listed in Table 1. Some alkyl chains, whose substituents had been shown in our previous study to be favorable for CB2 receptor affinity,24 were introduced at position 4 of phenyl, such as the bialkyl chain (dimethylamino, isopropoxyl, and isopropyl), monoalkyl chain substituents (ethoxyl, propoxyl, and butyl), and cycloalkanes (1-piperidinyl). Among them, 3 (R1 = diethylamino) and 6 (R1 = 1-piperidinyl) showed higher affinities for the CB2 receptor (53 and 44 nM, respectively) with a good CB2 selective index (SI = 43 and 28, respectively). These results indicated that longer chains and double chains are necessary for improving binding affinity in this scaffold.

Table 1. CB1 and CB2 Receptor Affinities of Compounds 3–12 with a Modified Zone A.

|

Ki (nM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | CB2a,b | CB1a,b | SIc |

| 3 | -N(CH2CH3)2 | 53 ± 6 | 2300 ± 200 | 43 |

| 4 | -N(CH3)2 | 680 ± 10 | NT | |

| 5 | -(CH2CH2Cl2)2 | 166 ± 4 | NT | |

| 6 | 1-piperidinyl | 44 ± 8 | 1300 ± 200 | 28 |

| 7 | -OCH(CH3)2 | 174 ± 7 | NT | |

| 8 | -OCH2CH3 | 230 ± 60 | NT | |

| 9 | -CH2CH2CH3 | 130 ± 20 | NT | |

| 10 | -CH2CH=CH2 | 130 ± 40 | NT | |

| 11 | -n-butyl | 280 ± 50 | NT | |

| 12 | -CH(CH3)2 | 230 ± 40 | NT | |

| SR144528d,e | 2.1 ± 0.4 | NT | ||

| SR141716d,f | NT | 11 ± 1 | ||

Binding affinities of compounds for CB1 and CB2 receptors were evaluated using the [3H]CP-55,940 radioligand competition binding assay. Data are means ± the standard error of the mean of at least three experiments performed in duplicate.

NT, not tested.

SI, selectivity index for CB2, calculated as the Ki(CB1)/Ki(CB2) ratio.

The binding affinities of reference compounds were evaluated in parallel with compounds 3–12 under the same conditions.

CB2 reference compound.

CB1 reference compound.

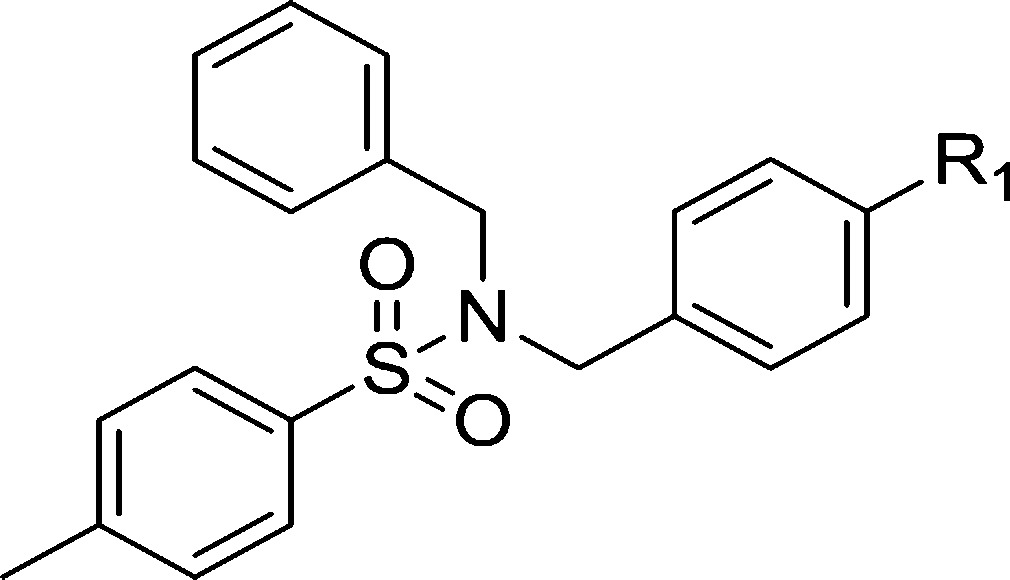

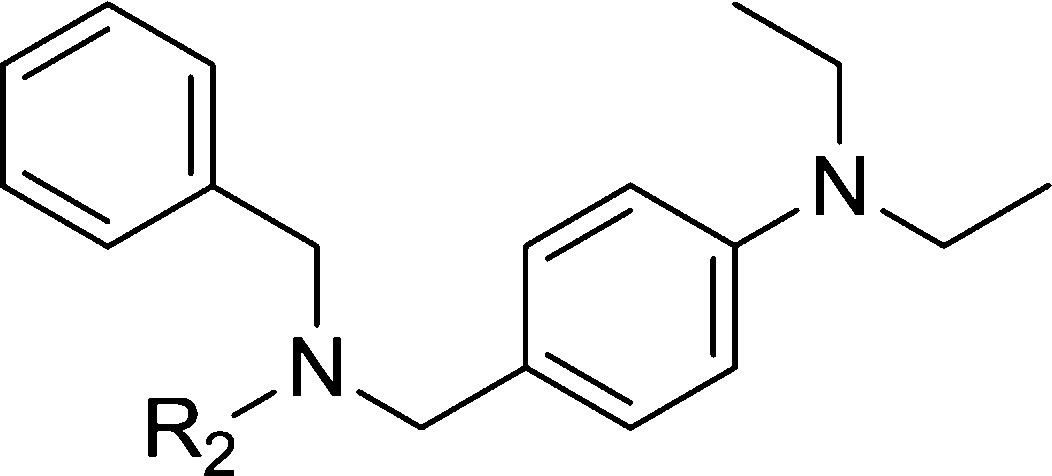

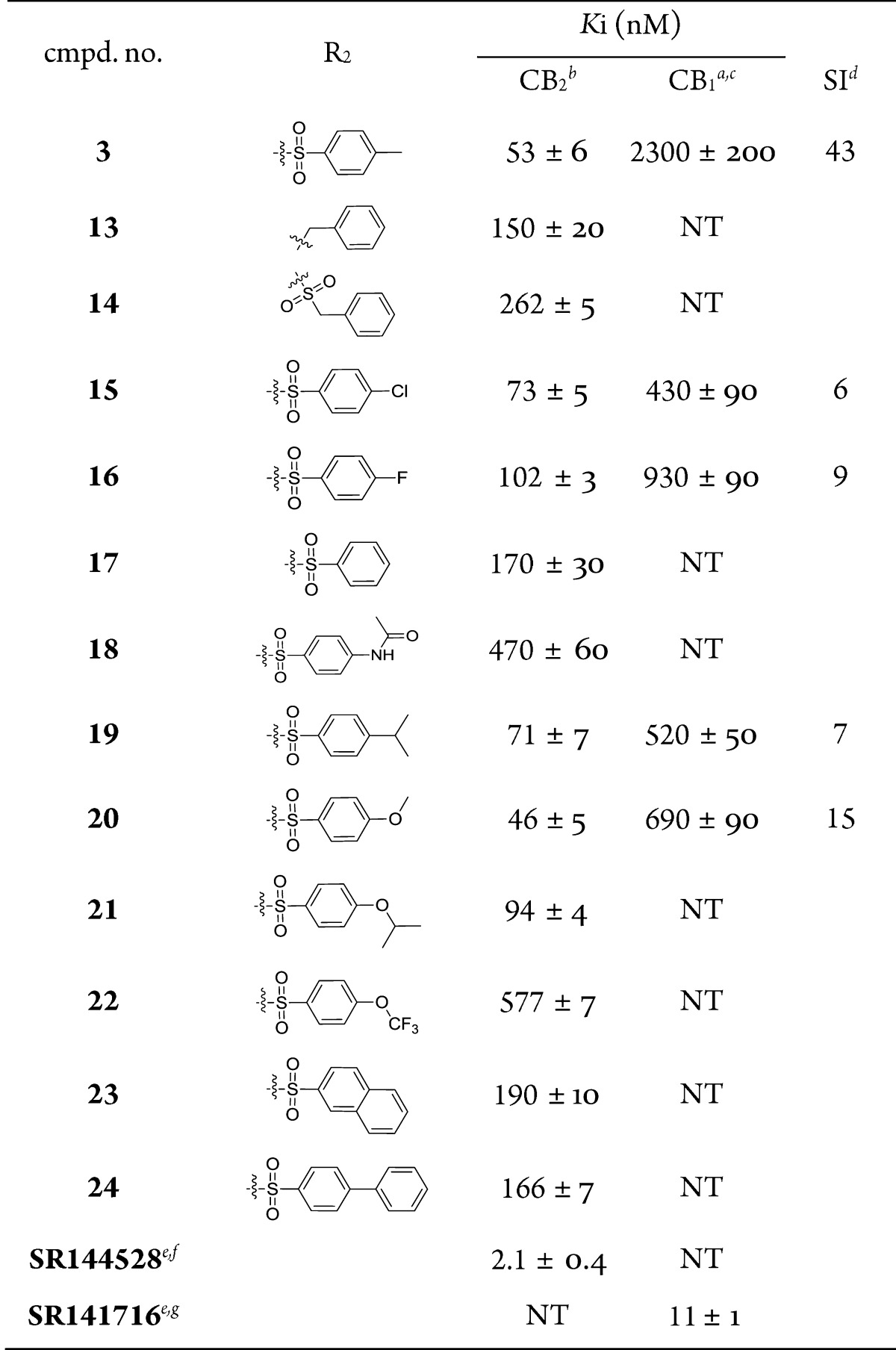

The modification of zone B was based on maintenance of the diethylamino group in zone A, as shown in Table 2. Compound 13, in which the sulfo group was replaced with a CH2 group, showed a slightly lower affinity. A similar result was found when a CH2 group was added between the sulfo and the phenyl group (14). Many substituents were introduced at position 4 of the sulfophenyl, such as Cl, F, H, acetylamide, isopropyl, methoxyl, isopropoxyl, and trifluoromethoxyl. Other than 20 (R2 = 4-methoxyphenyl), which had a binding affinity for the CB2 receptor (Ki = 46 nM) similar to that of 3, 13–22 did not show obvious increased binding affinity. Large groups, like naphthyl and 1,1′-biphenyl, were also used to replace the 4-methylphenyl. This replacement resulted in a lower binding affinity. These results indicated that 4-methylphenyl and 4-methoxylphenyl are the best groups among our modifications of zone B. Moreover, the CB2 selective indexes of 15, 16, 19, and 20 were quite low, ranging from 6 to 15.

Table 2. CB1 and CB2 Receptor Affinities of Compounds 13–24 with a Modified Zone B.

Same as the footnotes of Table 1.

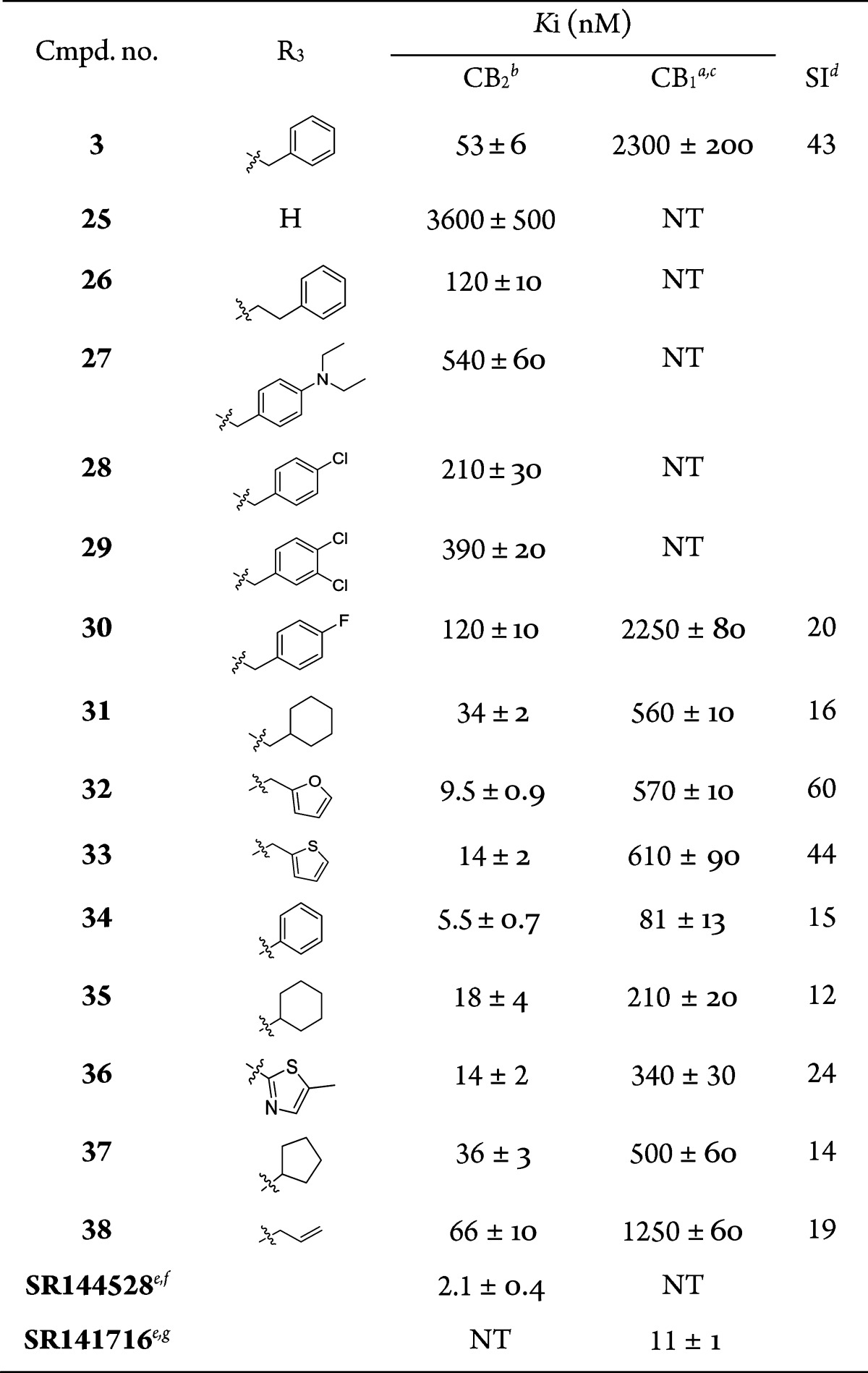

After investigation of the SAR of R1 and R2 in zones A and B, the binding affinities were not obviously improved. The following modification of group R3 in zone C was based on maintenance of the R1 and R2 groups in 3 (Table 3). As expected, group R3 is a key substituent for enhancing the CB2 affinity. First, another CH2 group was introduced at the N atom and the phenyl ring; compound 26 showed a lower CB2 binding affinity (Ki = 120 nM). The same reduced trends were found when diethylamino and halogen (Cl and F) were added to the phenyl ring in zone C. The binding affinities for the CB2 receptor of 27–30 were 540, 210, 390, and 120 nM, respectively. After substitution of the phenyl in zone C with cyclohexyl, a small increase in affinity was achieved [for 31, Ki(CB2) = 34 nM], while replacement by five-membered heterocyclic moieties (in 32 and 33) enhanced affinity dramatically, yielding a Ki values of 9.5 and 14 nM at CB2 receptors and 570 and 610 nM at CB1 receptors, respectively. It seemed that a smaller group in zone C is preferable for CB2 binding activity, so some compounds with smaller group were synthesized. Compound 34 with the reduced CH2 between the N atom in the core and phenyl group showed a higher CB2 binding affinity (Ki = 5.5 nM, and SI = 15). However, replacement with other smaller groups, such as cyclohexyl (35), 5-methylthiazolyl (36), cyclopentyl (37), and allyl (38), significantly reduced the binding activity [Ki(CB2) = 18, 14, 36, and 66 nM, respectively]. Especially, 25, without any substituted group except with an H atom at R3, showed quite low CB2 binding activity [Ki(CB2) = 3600 nM]. This result suggests that the space of the phenyl group is suitable for zone C and thus addition of a larger or smaller group results in lower CB2 binding activity.

Table 3. CB1 and CB2 Receptor Affinities of Compounds 25–38 with a Modified Zone C.

Same as the footnotes of Table 1.

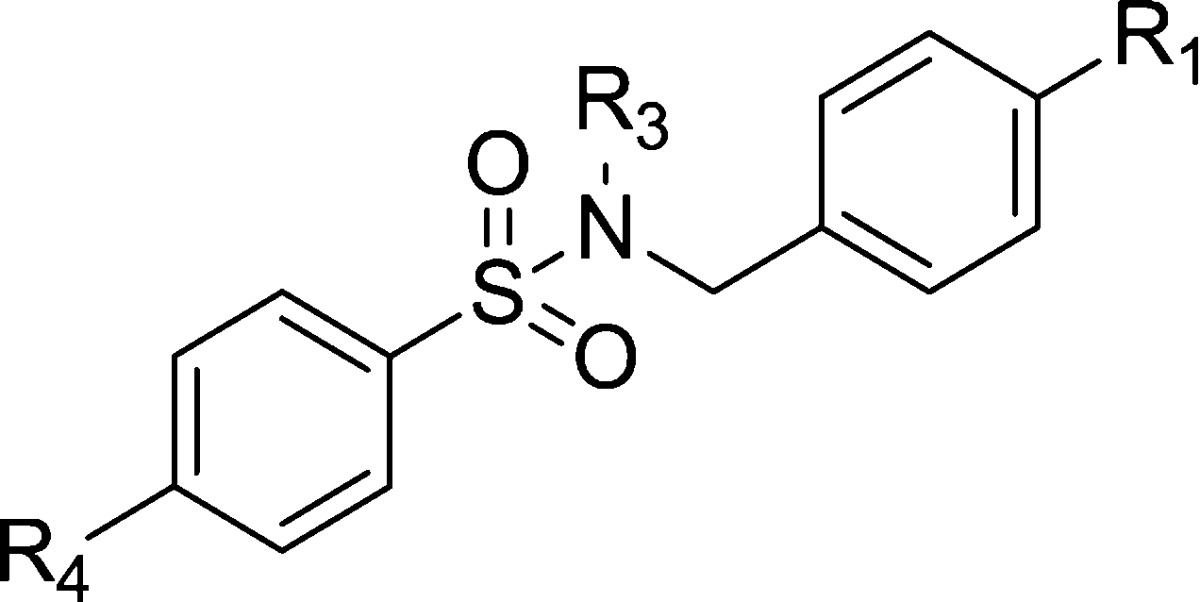

On the basis of the SAR research of zones A–C, we found that the introduction of some groups at R1–R3 could improve CB2 binding activity. Further SRA research was based on the compound library of combinations of these groups: R1 = diethylamino and 1-piperidinyl, R3 = phenyl, cyclohexyl, furan-2-ylmethyl, and 5-methylthiazolyl, and R4 = methoxyl, Cl, isopropyl, and methyl. The results are listed in Table 4 with the CB2 binding affinity ranging from 4 to 310 nM and the selective index ranging from 9 to 120. Among them, two compounds were identified with better CB2 binding activity and selectivity, 39 [Ki(CB2) = 5.4 nM, and SI = 92] and 45 [Ki(CB2) = 4.0 nM, and SI = 120].

Table 4. CB1 and CB2 Receptor Affinities of Compounds 39–48.

|

Ki (nM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | R3 | R4 | CB2a,b | CB1a,b | SIc |

| 39 | -N(CH2CH3)2 | phenyl | -OCH3 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 500 ± 60 | 92 |

| 40 | -N(CH2CH3)2 | phenyl | -CH(CH3)2 | 30 ± 4 | 2000 ± 200 | 66 |

| 41 | -N(CH2CH3)2 | furan-2-ylmethyl | -OCH3 | 20 ± 2 | 840 ± 80 | 42 |

| 42 | -N(CH2CH3)2 | furan-2-ylmethyl | -CH(CH3)2 | 31 ± 4 | 1300 ± 100 | 42 |

| 43 | -N(CH2CH3)2 | cyclohexyl | -OCH3 | 75 ± 6 | 660 ± 60 | 9 |

| 44 | -N(CH2CH3)2 | cyclohexyl | -CH(CH3)2 | 55 ± 2 | 1400 ± 100 | 25 |

| 45 | -N(CH2CH3)2 | 5-methylthiazolyl | -OCH3 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 600 ± 10 | 120 |

| 46 | 1-piperidinyl | phenyl | -CH3 | 310 ± 20 | NT | |

| 47 | 1-piperidinyl | phenyl | -OCH3 | 32 ± 7 | 590 ± 50 | 18 |

| 48 | 1-piperidinyl | phenyl | -Cl | 140 ± 10 | NT | |

| SR144528d,e | 2.1 ± 0.4 | NT | ||||

| SR141716d,f | NT | 11 ± 1 | ||||

Same as the footnotes of Table 1.

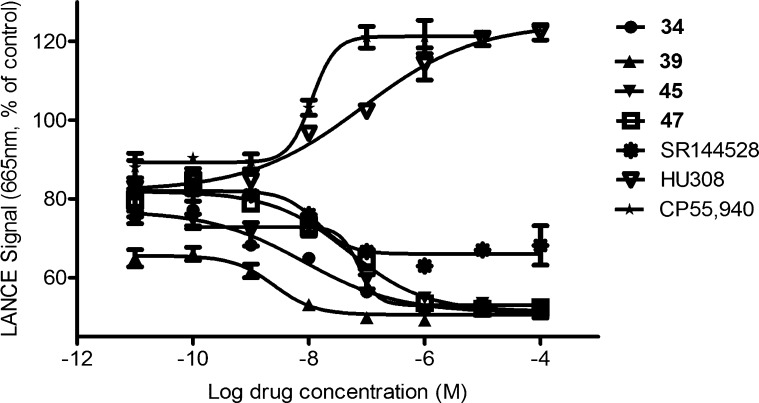

Functional properties were investigated in cAMP assays by using cell-based LANCE cAMP assays as our published protocol26 to measure the agonistic or antagonistic functional activities of the CB2-selective compounds. Because CB2 is a Gαi-coupled receptor, an agonist inhibits the forskolin-induced cAMP production, resulting in an increase in the magnitude of the LANCE signal, while an antagonist or inverse agonist decreases the magnitude of the LANCE signal. In addition to 34, 39, 45, and 47, with respective modifications in zones A–C for good binding activity, were selected for cAMP assays. As shown in Figure 2, reduction of the magnitude of the LANCE signal occurred with increasing concentrations of 34, 39, 45, 47, and SR144528 with EC50 values of 8.2 ± 3.1, 2.5 ± 1.4, 73 ± 2, 49 ± 2, and 14 ± 3 nM, respectively. Such a contrary phenomenon was observed with agonists CP55,940 and HU308,27 which showed cAMP production with EC50 values of 11 ± 2 and 85 ± 5 nM, respectively. On the basis of the LANCE signal change and the high EC50 value closely correlated with the high affinity value, it suggests that 34, 39, 45, and 47 behaved as CB2 receptor inverse agonists.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of the LANCE signal of different CB2 receptor ligands in stably transfected CHO cells expressing human CB2 receptors in a concentration-dependent fashion. EC50 values of compounds 34, 39, 45, 47, and SR144528 are 8.2 ± 3.1, 2.5 ± 1.4, 73 ± 2, 49 ± 2, and 14 ± 3 nM, respectively. EC50 values for CP55,940 and HU308 are 11 ± 2 and 85 ± 5 nM, respectively. Data are means ± the standard error of the mean of one representative experiment of two or more performed in duplicate or triplicate.

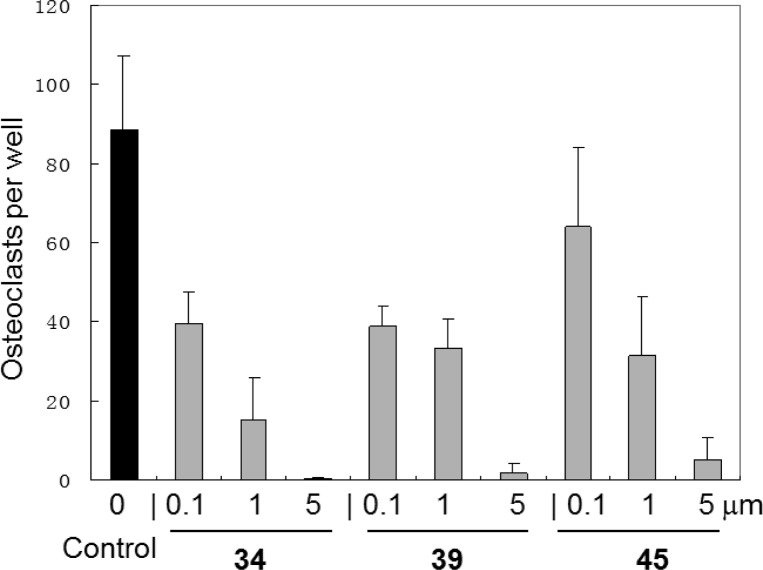

Modulating osteoclast function is a well-known activity of CB2 receptor agonists28 and inverse agonists.15c Three compounds, 34, 39, and 45, were selected on the basis of the results of binding affinity and selectivity, as well as their functionality as candidate inhibitors of osteoclast (OCL) formation. As shown in Figure 3, we tested the effects of these most promising CB2 ligands on osteoclast (OCL) formation using mouse bone marrow mononuclear cells treated by the mouse receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) plus macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (see the Supporting Information). These three compounds exhibited strong inhibition of osteoclastogenesis. Among them, 34 showed the most favorable activity. At 0.1, 1, and 5 μM, it suppressed osteoclast formation by 55, 83, and 99.7%, respectively. To investigate their cell toxicity, 34 was tested in a cytotoxicity assay without showing any cytotoxic effects at a concentration of 5 μM. These results indicate that our compounds possess favorable therapeutic indexes and the inhibition of osteoclastogenesis is not a result of their cytotoxicity.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of osteoclastogenesis by CB2 ligands 34, 39, and 45. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Results are means ± the standard deviation. Note that the control is vehicle control.

In summary, we have discovered the trisubstituted sulfonamide chemotype as a novel series possessing significant cannabinoid CB2 receptors affinity. Some compounds with high binding affinities and selective indexes of CB2 receptors were identified by optimization of zones A–C. The potencies of the novel compounds were measured in functional assays, with high potency values (represented by EC50) that are closely correlated with the high affinities (expressed as Ki), revealing that the novel series behaves as CB2 receptor inverse agonists. The promising inhibition activity to osteoclast cells of this novel series of compounds offers an attractive starting point for further optimization.

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic experimental details, analytical data, and biological assay protocols. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

We authors from the University of Pittsburgh gratefully acknowledge the financial support of our laboratory by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DA025612 and HL109654 (X.-Q.X.). We also acknowledge the collaboration support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC81090410, NSFC90913018, and NSFC21202201).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Matsuda L. A.; Lolait S. J.; Brownstein M. J.; Young A. C.; Bonner T. I. Structure of a Cannabinoid Receptor and Functional Expression of the Cloned Cdna. Nature 1990, 3466284561–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S.; Thomas K. L.; Abushaar M. Molecular Characterization of a Peripheral Receptor for Cannabinoids. Nature 1993, 365644161–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svizenska I.; Dubovy P.; Sulcova A. Cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2), their distribution, ligands and functional involvement in nervous system structures: A short review. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2008, 904501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickle M. D.; Duncan M.; Kingsley P. J.; Mouihate A.; Urbani P.; Mackie K.; Stella N.; Makriyannis A.; Piomelli D.; Davison J. S.; Marnett L. J.; Di Marzo V.; Pittman Q. J.; Patel K. D.; Sharkey K. A. Identification and functional characterization of brainstem cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Science 2005, 3105746329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood B. K.; Mackie K. CB2: A cannabinoid receptor with an identity crisis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 1603467–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee R. G.; Howlett A. C.; Abood M. E.; Alexander S. P. H.; Di Marzo V.; Elphick M. R.; Greasley P. J.; Hansen H. S.; Kunos G.; Mackie K.; Mechoulam R.; Ross R. A. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid Receptors and Their Ligands: Beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 624588–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar R.; Potluri V. K. Cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor: Pharmacology, role in pain and recent developments in emerging CB1 agonists. CNS Neurol. Disord.: Drug Targets 2011, 105536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggio P. H.The cannabinoid receptors; Humana: New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Malan T. P. Jr.; Ibrahim M. M.; Lai J.; Vanderah T. W.; Makriyannis A.; Porreca F. CB2 cannabinoid receptor agonists: Pain relief without psychoactive effects?. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2003, 3162–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P.; Mechoulam R. Is lipid signaling through cannabinoid 2 receptors part of a protective system?. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011, 502193–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecucco F.; Matias I.; Lenglet S.; Petrosino S.; Burger F.; Pelli G.; Braunersreuther V.; Mach F.; Steffens S.; Di Marzo V. Regulation and possible role of endocannabinoids and related mediators in hypercholesterolemic mice with atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2009, 2052433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Adler M. W.; Abood M. E.; Ganea D.; Jallo J.; Tuma R. F. CB2 receptor activation attenuates microcirculatory dysfunction during cerebral ischemic/reperfusion injury. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 78186–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murikinati S.; Juttler E.; Keinert T.; Ridder D. A.; Muhammad S.; Waibler Z.; Ledent C.; Zimmer A.; Kalinke U.; Schwaninger M. Activation of cannabinoid 2 receptors protects against cerebral ischemia by inhibiting neutrophil recruitment. FASEB J. 2010, 243788–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo A. A.; Sharkey K. A. Cannabinoids and the gut: New developments and emerging concepts. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 126121–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R.; Mousawy K.; Nagarkatti M.; Nagarkatti P. Endocannabinoids and immune regulation. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 60285–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorantla S.; Makarov E.; Roy D.; Finke-Dwyer J.; Murrin L. C.; Gendelman H. E.; Poluektova L. Immunoregulation of a CB2 Receptor Agonist in a Murine Model of NeuroAIDS. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 2010, 53456–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idris A. I.; van’t Hof R. J.; Greig I. R.; Ridge S. A.; Baker D.; Ross R. A.; Ralston S. H. Regulation of bone mass, bone loss and osteoclast activity by cannabinoid receptors. Nat. Med. 2005, 117774–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sophocleous A.; Landao-Bassonga E.; van’t Hof R. J.; Idris A. I.; Ralston S. H. The type 2 cannabinoid receptor regulates bone mass and ovariectomy-induced bone loss by affecting osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Endocrinology 2011, 15262141–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuehly W.; Paredes J. M. V.; Kleyer J.; Huefner A.; Anavi-Goffer S.; Raduner S.; Altmann K. H.; Gertsch J. Mechanisms of Osteoclastogenesis Inhibition by a Novel Class of Biphenyl-Type Cannabinoid CB2 Receptor Inverse Agonists. Chem. Biol. 2011, 1881053–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisanti S.; Bifulco M. Endocannabinoid system modulation in cancer biology and therapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 602107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.; Wang L.; Xie X. Q. Latest advances in novel cannabinoid CB2 ligands for drug abuse and their therapeutic potential. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 42187–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitio K. H.; Salo O. M. H.; Nevalainen T.; Poso A.; Jarvinen T. Targeting the cannabinoid CB2 receptor: Mutations, modeling and development of CB2 selective ligands. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12101217–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marriott K. S. C.; Huffman J. W. Recent advances in the development of selective ligands for the cannabinoid CB2 receptor. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2008, 83187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi-Carmona M.; Barth F.; Millan J.; Derocq J. M.; Casellas P.; Congy C.; Oustric D.; Sarran M.; Bouaboula M.; Calandra B.; Portier M.; Shire D.; Breliere J. C.; Le Fur G. SR 144528, the first potent and selective antagonist of the CB2 cannabinoid receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 2842644–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. A.; Brockie H. C.; Stevenson L. A.; Murphy V. L.; Templeton F.; Makriyannis A.; Pertwee R. G. Agonist inverse agonist characterization at CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors of L759633, L759656 and AM630. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 1263665–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda Y.; Miyagawa N.; Matsui T.; Kaya T.; Wamura H.; Iwamura H. Involvement of cannabinoid CB2 receptor-mediated response and efficacy of cannabinoid CB2 receptor inverse agonist, JTE-907, in cutaneous inflammation in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 5201–3164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn C. A.; Fine J. S.; Rojas-Triana A.; Jackson J. V.; Fan X. D.; Kung T. T.; Gonsiorek W.; Schwarz M. A.; Lavey B.; Kozlowski J. A.; Narula S. K.; Lundell D. J.; Hipkin R. W.; Bober L. A. A novel cannabinoid peripheral cannabinoid receptor-selective inverse agonist blocks leukocyte recruitment in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 3162780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z. X.; Peng X. Q.; Li X.; Song R.; Zhang H. Y.; Liu Q. R.; Yang H. J.; Bi G. H.; Li J.; Gardner E. L. Brain cannabinoid CB2 receptors modulate cocaine’s actions in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 1491160–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-Z.; Han X.-W.; Liu Q.; Makriyannis A.; Wang J.; Xie X.-Q. 3D-QSAR Studies of Arylpyrazole Antagonists of Cannabinoid Receptor Subtypes CB1 and CB2. A Combined NMR and CoMFA Approach. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 492625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X. Q.; Chen J. Z.; Billings E. M. 3D structural model of the G-protein-coupled cannabinoid CB2 receptor. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 2003, 532307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.; Myint K. Z.; Tong Q.; Feng R.; Cao H.; Almehizia A. A.; Hamed A. M.; Wang L.; Bartlow P.; Gao Y.; Gertsch J.; Teramachi J.; Kurihara N.; Roodman G. D.; Cheng T.; Xie X. Q. Lead Discovery, Chemistry Optimization and Biological Evaluation Studies of Novel Bi-amide Derivatives as CB2 Receptor Inverse Agonists and Osteoclast Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55229973–9987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint K. Z.; Wang L.; Tong Q.; Xie X. Q. Molecular fingerprint-based artificial neural networks QSAR for ligand biological activity predictions. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 9102912–2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. X.; Xie Z. J.; Wang L. R.; Schreiter B.; Lazo J. S.; Gertsch J.; Xie X. Q. Mutagenesis and computer modeling studies of a GPCR conserved residue W5.43(194) in ligand recognition and signal transduction for CB2 receptor. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 1191303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanus L.; Breuer A.; Tchilibon S.; Shiloah S.; Goldenberg D.; Horowitz M.; Pertwee R. G.; Ross R. A.; Mechoulam R.; Fride E. HU-308: A specific agonist for CB2, a peripheral cannabinoid receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999, 962514228–14233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofek O.; Karsak M.; Leclerc N.; Fogel M.; Frenkel B.; Wright K.; Tam J.; Attar-Namdar M.; Kram V.; Shohami E.; Mechoulam R.; Zimmer A.; Bab I. Peripheral cannabinoid receptor, CB2, regulates bone mass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 1033696–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.