Abstract

In recent years, emerging evidence has linked vitamin D not only to its known effects on calcium and bone metabolism, but also to many chronic illnesses involving neurocognitive decline. The importance of vitamin D3 in reducing the risk of these diseases continues to increase due to the fact that an increasing portion of the population in developed countries has a significant vitamin D deficiency. The older population is at an especially high risk for vitamin D deficiency due to the decreased cutaneous synthesis and dietary intake of vitamin D. Recent studies have confirmed an association between cognitive impairment, dementia, and vitamin D deficiency. There is a need for well-designed randomized trials to assess the benefits of vitamin D and lifestyle interventions in persons with mild cognitive impairment and dementia.

Keywords: vitamin D, 25(OH)D level, cognition, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia

Video abstract

Introduction

Vitamin D is involved in calcium and bone metabolism, as well as in numerous other metabolic processes that are important for maintaining health. Vitamin D deficiency is common in the elderly. In this review, we will summarize and discuss the current knowledge of the association between vitamin D levels and neurocognitive function. We will begin with overviews of vitamin D metabolism, vitamin D and aging, the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in the brain, malnutrition in the elderly, and the current evidence of vitamin D deficiency. Next, we will summarize new clinical data on the role of vitamin D among patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and vascular dementia (VaD).

Background

Vitamin D metabolism

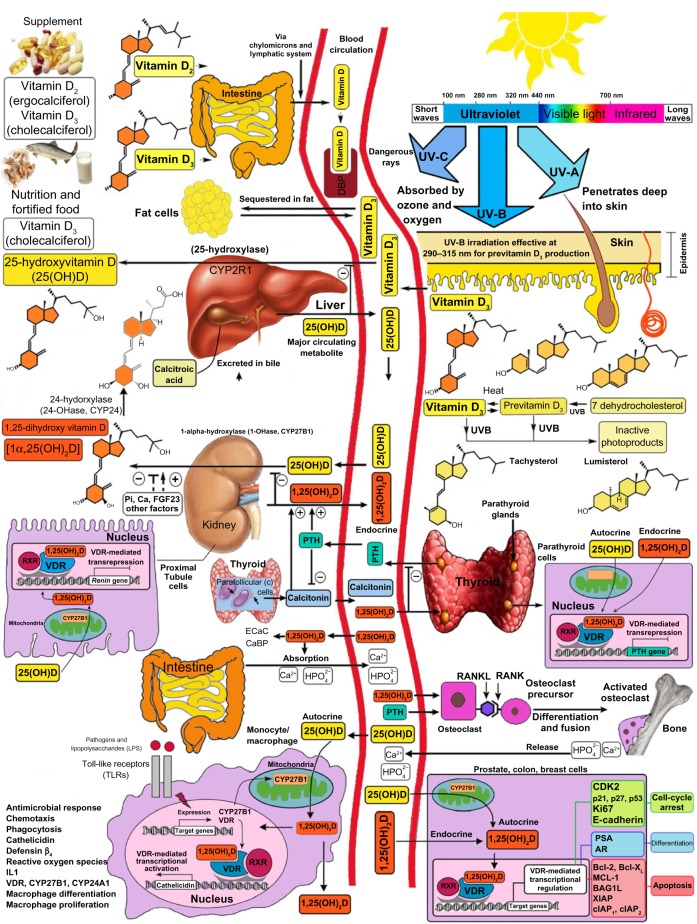

Vitamin D3 is produced in the human skin with the influence of sunlight (ultraviolet B; 290–315 nm) from 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC).1 Even though 7-DHC is the precursor of cholesterol, statins have no influence on the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3.2 Major factors that influence the cutaneous production of vitamin D3 include time of day, season, latitude, skin pigmentation, sunscreen use, and aging.3,4 Vitamin D (D represents D2 or D3) from cutaneous synthesis or dietary/supplemental intake is bound to the vitamin D binding protein and transported to the liver, where it is hydroxylated on C-25 by the cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP2R).1 In addition, 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] is the main circulating metabolite of vitamin D.1 In the kidneys, a second hydroxylation at the C1-position by the cytochrome P450 [5(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase; CYP27B1] occurs.1 This results in the production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], the biologically active metabolite of vitamin D.1 The concentration of 1,25(OH)2D in the blood is regulated via a feedback mechanism by 1,25(OH)2D itself (via an induction of the 25(OH)D–24-hydroxylase; CYP24A1), as well as by parathyroid hormone, calcium, fibroblast growth factor 23, and various cytokines such as interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor α (Figure 1).1,5 For a long time, it was assumed that only the kidneys were capable of converting 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D. In vitro experiments and studies in patients with nephrectomy have shown that numerous extrarenal cells, including keratinocytes, monocytes, macrophages, osteoblasts, prostate, and colon cells are capable of expressing the 1α-hydroxylase so as to convert 25(OH)D in these cells to 1,25(OH)2D.1,6,7 In keratinocytes, both the 1α-hydroxylase as well as the 25-hydroxylase (CYP2R) have been detected.6,8,9 Lehmann et al10 have shown in vitro that keratinocytes are capable of engaging in the complete enzymatic synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 from vitamin D3. Moreover, 1,25(OH)2D is produced locally in organs and cells, and it is thought to function in an autocrine manner to regulate a variety of metabolic processes that are not related to calcium metabolism. Once it performs these functions, it induces its own destruction by increasing the expression and production of CYP24A1, which hydroxylates and oxidizes the side chain, forming the inactive water-soluble calcitroic acid.1

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the synthesis and metabolism of vitamin D for skeletal and nonskeletal function.

Note: Copyright Holick 2013, reproduced with permission.

Abbreviations: DBP, vitamin D-binding protein; UV, ultraviolet; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; RXR, retinoic acid receptor; VDR, vitamin D receptor; Ecac, epithelial calcium channel; CaBP, calcium-binding protein; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TLR, toll-like receptor; PTH, parathyroid hormone; CDK2, cyclin-dependent kinase-2; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; AR, androgen receptor; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma; Bcl-XL, B-cell lymphoma–extra large; 1-OHase, 25-hydroxyvitamin D-la-hydroxylase; IDBP, intracellular D-binding protein; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; RNA, ribonucleic acid; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; 25-OHase, 25-hydroxyvitamin D-24-hydroxylase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; IL, interleukin; CYP, cytochrome P450; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein; MCL-1, myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein.

Vitamin D receptor in the brain

It should be noted that 1,25(OH)2D signaling is conducted through the VDR, which shares its structural characteristics with the broader nuclear steroid receptor family.11 In 1992, Sutherland et al12 provided the first evidence that the VDR is expressed in the human brain. Using radiolabeled complementary deoxyribonucleic acid probes, the authors showed that VDR messenger ribonucleic acid is expressed in the postmortem brains of patients with AD or Huntington’s disease. In a landmark study, Eyles et al13 described that both the VDR and CYP27B1 are widespread in important regions of the human brain including the hippocampus, which is particularly affected by neurodegenerative disorders.14–17 Furthermore, the VDR is also expressed in the prefrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus, basal forebrain, caudate/putamen, thalamus, substantia nigra, lateral geniculate nuclei, hypothalamus, and cerebellum.18 Importantly, VDR gene polymorphisms are associated with cognitive decline,19,20 AD,21–24 Parkinson’s disease,25–29 and multiple sclerosis.30

Vitamin D and aging

With age, the skin’s ability to synthesize vitamin D significantly decreases. MacLaughlin and Holick31 described that the capacity of the skin’s ability to synthesize vitamin D is reduced by more than 50% at 70 years of age compared to 20 years of age; however, aging does not affect the intestinal absorption of vitamin D. While hydroxylation at the C-25 position in the liver is not affected by aging,32 the ability for the hydroxylation at the C-1 position is reduced by age-related functional limitations of the kidneys, and is less responsive to the parathyroid hormone stimulation of CYP27B1.33,34 Decreased thickness of the skin with age,35 in addition to a reduction in 7-DHC content is considered the reason for the decrease in vitamin D synthesis with aging.31 In 1989, Holick et al36 described that a single exposure to simulated solar radiation (32 mJ/cm2) in younger subjects led to a significant threefold increase in serum vitamin D3 concentration, as compared to elderly subjects. Several studies have reported that 25(OH)D <30 ng/mL is common in older persons with illnesses.37–39 Perry et al40 also described that there is a longitudinal decline in 25(OH)D levels with aging, even in those taking a vitamin D supplement.

Malnutrition in the elderly

Malnutrition is not a symptom of old age, but it often accompanies one or more diseases, and its clinical presentation is often nonspecific. The type and intensity of symptoms depend on the patient’s prior nutritional status and on the nature of the underlying disease and the speed at which it is progressing.41 Malnutrition can be a causative factor not only for vitamin D deficiency, but for other fat and water-soluble vitamins that are important for neurocognitive function. Alterations in smell42 and taste perception,43 as well as in chewing and swallowing disorders,44 lead to a decrease in the enjoyment of food and may contribute to the reduction of energy consumption. Pain, nausea, and polypharmacy are among the most common reasons that many hospital patients do not consume enough nutrients.45 Nutrient loss can be accelerated by bleeding, diarrhea, abnormally high sugar levels (glycosuria), kidney disease, and other factors such as fever, infection, surgery, or benign or malignant tumors. Furthermore, life events, such as the loss of a spouse, or social factors, such as the nature and extent of nursing support,46 have a significant impact on energy consumption. Patients with depression47 and most patients with dementia are at a higher risk for malnutrition during the course of their disease,48 and ensuring adequate oral intake within the group of patients with dementia is often problematic.49–51 A recent meta-analysis of 12 articles evaluated the effectiveness of oral nutritional supplements (ONS) in older adults with and without cognitive impairment.52 The authors showed that patients exhibited a significant improvement in weight (P<0.0001), body mass index (P<0.0001), and cognition at a 6.5±3.9-month follow up (P=0.002) when ONS were given, as compared to the control group.52

However, caution should be applied to the finding regarding the influence of ONS on cognitive performance, as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), since only four studies with a total of 141 patients in the intervention groups and 130 in the control groups were included.52

Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency

According to the US Endocrine Society, which addresses the evaluation and treatment of patients with specific diseases who are at risk for vitamin D deficiency, a cut-off level <20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) for 25(OH)D defined vitamin D deficiency.53 The US Institute of Medicine report, which addresses the dietary reference intake of vitamin D in the normal, healthy North American population, concluded that 25(OH)D equal to 16 ng/mL (40 nmol/L) should be the cut-off for vitamin D deficiency, but for maximum bone health, the team recommended a 25(OH)D level >20 ng/mL.54 Recent reviews reported that children, as well as young, middle-aged, and older adults are at risk for vitamin D deficiency worldwide.55–57 In Europe, vitamin D deficiency in the elderly is more likely in women than in men, and it is more common in the south than in the north.58 Based on the definition of the US Endocrine Society, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was almost one-third of the US population.59 Data from the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence (HELENA) study, which obtained blood samples from 1,006 adolescents in nine different European countries, also indicated that vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent, even in children.60 Importantly, vitamin D deficiency is associated with a significantly increased prevalence of hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and endothelial dysfunction.61,62

Vitamin D and neurocognitive functioning

There is strong evidence that 1,25(OH)2D contributes to neuroprotection by modulating the production of nerve growth,63–65 decreasing L-type calcium channel expression,66 regulating the toxicity of reactive oxygen species,67–71 and neurotrophic factors such as nerve growth factor,64,72–76 glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor,77 and nitric oxide synthase.69 Furthermore, vitamin D and its metabolites are involved in other neuroprotective mechanisms including amyloid phagocytosis and clearance,78,79 and vasoprotection.80

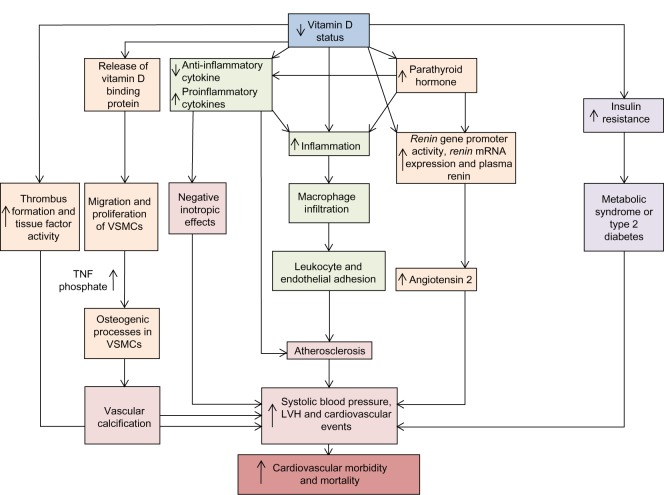

Multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies confirm that cardiovascular risk factors (for example, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, and smoking) are associated with low levels of 25(OH)D and predict cardiovascular events including strokes.81–86 Gunta et al86 recently described multiple vitamin-D-related pathways that contribute to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Vitamin D plays a protective role in the cardiovascular system through downregulating the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system,87–90 cardiac remodeling,91–93 regulating the endothelial response to injury,94–96 and blood coagulation by increasing thrombus formation and tissue factor activity (Figure 2).97 Furthermore, 25(OH)D levels are inversely associated with one’s risk for developing vascular calcification,98,99 which is known as a marker of atherosclerotic burden and a risk factor for dementia.100–103

Figure 2.

Vitamin D-related pathways, cardiovascular morbidity, and mortality.

Notes: A decreased serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (vitamin D status) is a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, owing to increases in systolic blood pressure, LVH, and adverse cardiovascular events. These effects may involve various pathways, including increases in endothelial adhesion, which could promote atherosclerosis causing negative inotropic effects on the heart, vascular calcification through osteogeneic processes in VSMCs, and an increase in thrombogenesis. Furthermore, increases in the inflammatory milieu cause macrophage infiltration, and increased levels of parathyroid hormone could be involved in a complex interaction with the renin–angiotensin system. Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Reviews Nephrology. Gunta SS, Thadhani RI, Mak RH. The effect of vitamin D status on risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9(6):337–347.86 Copyright © 2013.

Abbreviations: TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; mRNA, messenger RNA.

In recent years, the relationship between blood pressure and cognitive function and dementia has received much attention from epidemiological research. It is known that midlife hypertension is an important modifiable risk factor for late-life cognitive decline,104,105 MCI106,107 and VaD.108,109 Qiu et al110 described that some cross-sectional studies have shown an inverse association between blood pressure and the prevalence of dementia and AD, whereas longitudinal studies yielded mixed results that largely depend on the age at which blood pressure is measured and the time interval between blood pressure and outcome assessments.

A recent American Heart Association and American Stroke Association guidance statement published in 2011 provided an excellent overview of the evidence on vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia.111 There is reasonable evidence (class 2a, Level of Evidence B) to suggest that blood pressure-lowering therapy can be useful for the prevention of late-life dementia among people who are middle-aged, and for younger elderly individuals. However, the usefulness of lowering blood pressure in those over 80 years of age for the prevention of dementia is not well established (class 2b, Level of Evidence B). Furthermore, lowering blood pressure in patients who do not have cognitive impairment can reduce the risk of subsequent cognitive impairment, whereas lowering blood pressure to preserve cognition among patients who already have cognitive impairment is not a proven successful strategy.

In 2010, The National Institutes of Health launched a two-arm, multicenter, randomized clinical trial to determine whether maintaining blood pressure levels lower than the current recommendations further reduces one’s risk of developing cardiovascular and kidney diseases, or age-related cognitive decline. Called the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), this 9-year, $114 million study will be conducted in more than 80 clinical sites across the United States. More than 9,000 patients >55 years of age with systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg and with at least one other vascular risk factor will be randomized to either an “aggressive” treatment arm characterized by a target systolic blood pressure of <120 mmHg, or a more “routine” arm with a target systolic blood pressure of <140 mmHg. In a substudy (SPRINT-MIND) – which is funded by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–whether the lower systolic blood pressure goal influences the occurrence of dementia, change in cognition, and change in brain structure (on magnetic resonance imaging) will also be tested.

Vitamin D and mild cognitive impairment

MCI is a condition that “represents an intermediate state of cognitive function between the changes seen in aging but does not fulfill the criteria for dementia.”112 Petersen112 estimated that between 10% and 20% of people aged 65 years or older suffer from MCI, and several other studies have shown that patients with MCI are at a greater risk of developing dementia.113–116 A meta-analysis by Etgen et al117 suggested a more than doubled risk of cognitive impairment in patients with vitamin D deficiency among 7,688 participants. The authors showed an increased risk of developing cognitive impairment in those with low 25(OH)D compared with those with normal 25(OH)D levels (odds ratio: 2.39; 95% confidence interval: 1.91–3.00; P<0.0001). Only five cross-sectional and two longitudinal studies were included in the meta-analysis, which underlines the need for future prospective studies.

One of the studies by Llewellyn et al118 showed an inverse relationship with serum 25(OH)D and cognitive impairment in 1,766 adults aged 65 years and older from the Health Survey for England 2000. There was a 230% increased risk for cognitive impairment in those with 25(OH)D <20 ng/mL compared to those with a 25(OH)D level >20 ng/mL. Including 2,749 participants from eight studies, Balion et al119 compared mean MMSE scores between individuals with levels of 25(OH)D <50 nmol/L and ≥50 nmol/L. The authors showed a higher average MMSE score in those participants with higher 25(OH)D concentrations. There is also a need for long-term, placebo-controlled, randomized trials to assess the potential benefits of pharmacologic and lifestyle interventions in persons with MCI. A very promising randomized-controlled trial (DO-HEALTH) began enrolling participants in December 2012; it will enroll a total of 2,152 community-dwelling men and women aged 70 years of age to test the individual and the combined benefits of 2,000 IU of vitamin D/day, 1 g of omega-3 fatty acids/day, and a simple home exercise program (http://do-health.eu/wordpress/). One of the five primary endpoints is the risk of functional decline.

Vitamin D, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia

AD is the best known and the most common cause of dementia in older people.120 According to a study by Ferri et al121 that was conducted in 2005, the global prevalence of dementia was 24.3 million. The authors hypothesized that this number will double every 20 years to a total of 42 million individuals by 2020 and 81 million people by 2040. VaD is the second most common type of dementia.122–124 According to The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS), the prevalence of VaD in the United States among those aged 71 years and older has been estimated to be approximately 594,000.125 The development of clinical AD and VaD is very complex,126,127 since several pathophysiological pathways leading to vascular and neurodegenerative processes are similar.128 Importantly, macroscopic infarcts are very common in approximately one-third to one-half of older people,129–132 and infarcts frequently coexist with AD pathology in the brains of older people.130,132–136 Several studies showed that cerebrovascular lesions lower the threshold of the AD-type changes that are necessary to cause cognitive decline.133,135,137

It has to be acknowledged that the prevalence and incidence figures from AD and VaD pertain to diagnostic thresholds for these disorders,111 and that there exist multiple sets of criteria for VaD.124 Most older studies use the construct of VaD, and more recently, the term “vascular cognitive impairment” has been introduced to capture the entire spectrum of cognitive disorders that range from MCI to fully developed dementia.111 Since most of the recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses that have been published within the last 3–5 years, the old term (VaD) has been used to characterize cognitive syndromes associated with vascular disease and cognitive decline. A meta-analysis from Balion et al,119 which was conducted using five different databases including 37 different studies published in 2012, compared cognition (as measured by the MMSE) to 25(OH)D levels. The results showed that individuals with AD had lower 25(OH)D concentrations compared to those without AD. In addition, MMSE scores were lower in patients with lower 25(OH)D concentrations. However, the authors noted that the nature of the relationship between cognition and 25(OH)D concentrations is still not clear. In contrast to Balion et al,119 who included studies with and without regression models to answer this question, Annweiler et al114 restricted their report to studies that used regression models. The authors concluded that in older adults, vitamin D deficiency was associated with dementia,138–141 and that vitamin D supplementation might have a protective effect. Similar results were reported by Barnard and Colón-Emeric.142 Furthermore, in a systematic review and meta-analysis, Annweiler et al143 critically analyzed the domain-specific cognitive performance affected in vitamin D deficiency. The authors demonstrated that vitamin D deficiency “is cross-sectionally associated in adults with episodic memory disorders and executive dysfunctions, in particular mental shifting, information updating, and processing speed.”143 Recently, van der Schaft et al144 also conducted a systematic review that included 25 studies with a cross-sectional design and six studies with a prospective design; three of these studies showed cross-sectional as well as prospective data.145–147 The main finding was a statistically significantly worse outcome on one or more cognitive function tests, or a higher frequency of dementia, with lower 25(OH)D levels or vitamin D intake in 72% of the studies. In addition, 67% of the prospective studies showed a higher risk of cognitive decline after a follow-up period of 4–7 years in participants with lower 25(OH)D levels at baseline compared with participants with higher 25(OH)D levels.

Importantly, several limitations have to be considered while interpreting the data of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Cross-sectional studies cannot answer the question of whether vitamin D deficiency leads to cognitive decline, or whether people with a cognition disorder have lower exposure to sunlight or lower vitamin D intake, nor do they reflect seasonal fluctuation of vitamin D status.144 Using different cut-off points for vitamin D status classification, and different diagnostic criteria for MCI and VaD, make it difficult to compare these studies. Finally, the differences in adjustments for potential confounders such as age, sex, race, depression, level of education, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, physical activity, and/or season that the sample was obtained may explain some of the different study results reported in the systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Conclusion

Older adults are at a high risk of developing vitamin D deficiency due to decreased cutaneous synthesis and dietary intake of vitamin D. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with substantial increases in the incidence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, myocardial infarction, stroke, fractures, and diabetes. Vitamin D signaling is involved in brain development and function. Many studies have shown that AD and VaD share hypertension as a common risk factor, and there is reasonable evidence to suggest blood pressure-lowering therapy can be useful for the prevention of late-life dementia for middle-aged and younger elderly individuals, whereas the usefulness of lowering blood pressure among those over 80 years of age for the prevention of dementia is not well established. The overlap between AD and VaD makes it difficult to estimate to what extent each disease contributes to cognitive decline. The majority of the cross-sectional and prospective studies found that vitamin D deficiency is associated with a statistically significantly worse outcome on one or more cognitive function tests, or with a higher frequency of MCI and dementia. The identification of people who are at risk for cognitive impairment holds realistic promise for the prevention or postponement of dementia. There is a need for long-term, placebo-controlled, randomized trials to assess the potential benefits of pharmacologic and lifestyle interventions in persons with MCI, VaD, and AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health Clinical Translational Science Institute Grant UL-1-RR-25711.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobs AS, Levine MA, Margolis S. Effects of pravastatin, a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, on vitamin D synthesis in man. Metabolism. 1991;40(5):524–528. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(91)90235-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godar DE, Pope SJ, Grant WB, Holick MF. Solar UV doses of adult Americans and vitamin D(3) production. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3(4):243–250. doi: 10.4161/derm.3.4.15292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holick MF. Optimal vitamin D status for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Drugs Aging. 2007;24(12):1017–1029. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724120-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holick MF. Evolution and function of vitamin D. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2003;164:3–28. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55580-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehmann B, Tiebel O, Meurer M. Expression of vitamin D3 25-hydroxylase (CYP27) mRNA after induction by vitamin D3 or UVB radiation in keratinocytes of human skin equivalents – a preliminary study. Arch Dermatol Res. 1999;291(9):507–510. doi: 10.1007/s004030050445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bikle DD, Halloran BP, Riviere JE. Production of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 by perfused pig skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102(5):796–798. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12378190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seifert M, Tilgen W, Reichrath J. Expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1alpha-hydroxylase (1alphaOHase, CYP27B1) splice variants in HaCaT keratinocytes and other skin cells: modulation by culture conditions and UV-B treatment in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(9):3659–3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu GK, Lin D, Zhang MY, et al. Cloning of human 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1 alpha-hydroxylase and mutations causing vitamin D-dependent rickets type 1. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11(13):1961–1970. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.13.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehmann B, Genehr T, Knuschke P, Pietzsch J, Meurer M. UVB-induced conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in an in vitro human skin equivalent model. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(5):1179–1185. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83(6):835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland MK, Somerville MJ, Yoong LK, Bergeron C, Haussler MR, McLachlan DR. Reduction of vitamin D hormone receptor mRNA levels in Alzheimer as compared to Huntington hippocampus: correlation with calbindin-28k mRNA levels. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;13(3):239–250. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, Hewison M, McGrath JJ. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhikav V, Anand K. Potential predictors of hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(1):1–11. doi: 10.2165/11586390-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mu Y, Gage FH. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and its role in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:85. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fotuhi M, Do D, Jack C. Modifiable factors that alter the size of the hippocampus with ageing. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(4):189–202. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calabresi P, Castrioto A, Di Filippo M, Picconi B. New experimental and clinical links between the hippocampus and the dopaminergic system in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):811–821. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimitphong H, Holick MF. Vitamin D, neurocognitive functioning and immunocompetence. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14(1):7–14. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283414c38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beydoun MA, Ding EL, Beydoun HA, Tanaka T, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB. Vitamin D receptor and megalin gene polymorphisms and their associations with longitudinal cognitive change in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(1):163–178. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.017137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuningas M, Mooijaart SP, Jolles J, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RG, van Heemst D. VDR gene variants associate with cognitive function and depressive symptoms in old age. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(3):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luedecking-Zimmer E, DeKosky ST, Nebes R, Kamboh MI. Association of the 3′ UTR transcription factor LBP-1c/CP2/LSF polymorphism with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2003;117B(1):114–117. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gezen-Ak D, Dursun E, Ertan T, et al. Association between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and Alzheimer’s disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2007;212(3):275–282. doi: 10.1620/tjem.212.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehmann DJ, Refsum H, Warden DR, Medway C, Wilcock GK, Smith AD. The vitamin D receptor gene is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2011;504(2):79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gezen-Ak D, Dursun E, Bilgiç B, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene haplotype is associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228(3):189–196. doi: 10.1620/tjem.228.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JS, Kim YI, Song C, et al. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease in Koreans. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20(3):495–498. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler MW, Burt A, Edwards TL, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene as a candidate gene for Parkinson disease. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75(2):201–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2010.00631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han X, Xue L, Li Y, Chen B, Xie A. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and its association with Parkinson’s disease in Chinese Han population. Neurosci Lett. 2012;525(1):29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lv Z, Tang B, Sun Q, Yan X, Guo J. Association study between vitamin d receptor gene polymorphisms and patients with Parkinson disease in Chinese Han population. Int J Neurosci. 2013;123(1):60–64. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.726669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Török R, Török N, Szalardy L, et al. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and Parkinson’s disease in Hungarians. Neurosci Lett. 2013;551:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krizova L, Kollar B, Jezova D, Turcani P. Genetic aspects of vitamin D receptor and metabolism in relation to the risk of multiple sclerosis. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2013 Sep 26; doi: 10.4149/gpb_2013067. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacLaughlin J, Holick MF. Aging decreases the capacity of human skin to produce vitamin D3. J Clin Invest. 1985;76(4):1536–1538. doi: 10.1172/JCI112134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris SS, Dawson-Hughes B. Plasma vitamin D and 25OHD responses of young and old men to supplementation with vitamin D3. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21(4):357–362. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallagher JC, Rapuri P, Smith L. Falls are associated with decreased renal function and insufficient calcitriol production by the kidney. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3–5):610–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armbrecht HJ, Zenser TV, Davis BB. Effect of age on the conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by kidney of rat. J Clin Invest. 1980;66(5):1118–1123. doi: 10.1172/JCI109941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Need AG, Morris HA, Horowitz M, Nordin C. Effects of skin thickness, age, body fat, and sunlight on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58(6):882–885. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.6.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holick MF, Matsuoka LY, Wortsman J. Age, vitamin D, and solar ultraviolet. Lancet. 1989;2(8671):1104–1105. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gau JT. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency practice patterns in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(4):296. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.12.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morley JE. Vitamin d redux. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(9):591–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braddy KK, Imam SN, Palla KR, Lee TA. Vitamin d deficiency/insufficiency practice patterns in a veterans health administration long-term care population: a retrospective analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(9):653–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perry HM, Horowitz M, Morley JE, et al. Longitudinal changes in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in older people. Metabolism. 1999;48(8):1028–1032. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welge-Lüssen A. Ageing, neurodegeneration, and olfactory and gustatory loss. B-ENT. 2009;5(Suppl 13):129–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Methven L, Allen VJ, Withers CA, Gosney MA. Ageing and taste. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71(4):556–565. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guiglia R, Musciotto A, Compilato D, et al. Aging and oral health: effects in hard and soft tissues. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(6):619–630. doi: 10.2174/138161210790883813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zadak Z, Hyspler R, Ticha A, Vlcek J. Polypharmacy and malnutrition. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(1):50–55. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32835b612e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamura BK, Bell CL, Masaki KH, Amella EJ. Factors associated with weight loss, low BMI, and malnutrition among nursing home patients: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(9):649–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, Lonterman-Monasch S, de Vries OJ, Danner SA, Kramer MH, Muller M. Prevalence and determinants for malnutrition in geriatric outpatients. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(6):1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roqué M, Salvà A, Vellas B. Malnutrition in community-dwelling adults with dementia (NutriAlz Trial) J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(4):295–299. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0401-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikeda M, Brown J, Holland AJ, Fukuhara R, Hodges JR. Changes in appetite, food preference, and eating habits in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73(4):371–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.4.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manthorpe J, Watson R. Poorly served? Eating and dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(2):162–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenwood CE, Tam C, Chan M, Young KW, Binns MA, van Reekum R. Behavioral disturbances, not cognitive deterioration, are associated with altered food selection in seniors with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(4):499–505. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allen VJ, Methven L, Gosney MA. Use of nutritional complete supplements in older adults with dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Clin Nutr. 2013 Mar 28; doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.03.015. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Endocrine Society Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium; Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, editors. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hagenau T, Vest R, Gissel TN, et al. Global vitamin D levels in relation to age, gender, skin pigmentation and latitude: an ecologic meta-regression analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(1):133–140. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wahl DA, Cooper C, Ebeling PR, et al. A global representation of vitamin D status in healthy populations. Arch Osteoporos. 2012;7(1–2):155–172. doi: 10.1007/s11657-012-0093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hossein-Nezhad A, Holick MF. Vitamin d for health: a global perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(7):720–755. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Wielen RP, Löwik MR, van den Berg H, et al. Serum vitamin D concentrations among elderly people in Europe. Lancet. 1995;346(8969):207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganji V, Zhang X, Tangpricha V. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and prevalence estimates of hypovitaminosis D in the US population based on assay-adjusted data. J Nutr. 2012;142(3):498–507. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.151977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valtueña J, Gracia-Marco L, Huybrechts I, et al. Helena Study Group Cardiorespiratory fitness in males, and upper limbs muscular strength in females, are positively related with 25-hydroxyvitamin D plasma concentrations in European adolescents: the HELENA study. QJM. 2013;106(9):809–821. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson JL, May HT, Horne BD, et al. Intermountain Heart Collaborative (IHC) Study Group Relation of vitamin D deficiency to cardiovascular risk factors, disease status, and incident events in a general healthcare population. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(7):963–968. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kienreich K, Tomaschitz A, Verheyen N, et al. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 2013;5(8):3005–3021. doi: 10.3390/nu5083005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chabas JF, Alluin O, Rao G, et al. Vitamin D2 potentiates axon regeneration. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25(10):1247–1256. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown J, Bianco JI, McGrath JJ, Eyles DW. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces nerve growth factor, promotes neurite outgrowth and inhibits mitosis in embryonic rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2003;343(2):139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marini F, Bartoccini E, Cascianelli G, et al. Effect of 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in embryonic hippocampal cells. Hippocampus. 2010;20(6):696–705. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brewer LD, Thibault V, Chen KC, Langub MC, Landfield PW, Porter NM. Vitamin D hormone confers neuroprotection in parallel with downregulation of L-type calcium channel expression in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21(1):98–108. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00098.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ibi M, Sawada H, Nakanishi M, et al. Protective effects of 1 alpha, 25-(OH)(2)D(3) against the neurotoxicity of glutamate and reactive oxygen species in mesencephalic culture. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40(6):761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kröncke KD, Klotz LO, Suschek CV, Sies H. Comparing nitrosative versus oxidative stress toward zinc finger-dependent transcription. Unique role for NO. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(15):13294–13301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garcion E, Sindji L, Montero-Menei C, Andre C, Brachet P, Darcy F. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase during rat brain inflammation: regulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Glia. 1998;22(3):282–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen KB, Lin AM, Chiu TH. Systemic vitamin D3 attenuated oxidative injuries in the locus coeruleus of rat brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;993:313–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07539.x. discussion 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin AM, Fan SF, Yang DM, Hsu LL, Yang CH. Zinc-induced apoptosis in substantia nigra of rat brain: neuroprotection by vitamin D3. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34(11):1416–1425. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wion D, MacGrogan D, Neveu I, Jehan F, Houlgatte R, Brachet P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a potent inducer of nerve growth factor synthesis. J Neurosci Res. 1991;28(1):110–114. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490280111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Neveu I, Naveilhan P, Baudet C, Brachet P, Metsis M. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates NT-3, NT-4 but not BDNF mRNA in astrocytes. Neuroreport. 1994;6(1):124–126. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412300-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neveu I, Naveilhan P, Jehan F, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates the synthesis of nerve growth factor in primary cultures of glial cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;24(1–4):70–76. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Musiol IM, Feldman D. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induction of nerve growth factor in L929 mouse fibroblasts: effect of vitamin D receptor regulation and potency of vitamin D3 analogs. Endocrinology. 1997;138(1):12–18. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Veenstra TD, Fahnestock M, Kumar R. An AP-1 site in the nerve growth factor promoter is essential for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-mediated nerve growth factor expression in osteoblasts. Biochemistry. 1998;37(17):5988–5994. doi: 10.1021/bi972965+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Naveilhan P, Neveu I, Wion D, Brachet P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3, an inducer of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroreport. 1996;7(13):2171–2175. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199609020-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Masoumi A, Goldenson B, Ghirmai S, et al. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 interacts with curcuminoids to stimulate amyloid-beta clearance by macrophages of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(3):703–717. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mizwicki MT, Liu G, Fiala M, et al. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and resolvin D1 retune the balance between amyloid-β phagocytosis and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34(1):155–170. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S, et al. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality-a review of recent evidence. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(10):976–989. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Witham MD, Nadir MA, Struthers AD. Effect of vitamin D on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2009;27(10):1948–1954. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832f075b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pilz S, Tomaschitz A, März W, et al. Vitamin D, cardiovascular disease and mortality. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75(5):575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Muscogiuri G, Sorice GP, Ajjan R, et al. Can vitamin D deficiency cause diabetes and cardiovascular diseases? Present evidence and future perspectives. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22(2):81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang L, Song Y, Manson JE, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxy-vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(6):819–829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brøndum-Jacobsen P, Nordestgaard BG, Schnohr P, Benn M. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and symptomatic ischemic stroke: an original study and meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(1):38–47. doi: 10.1002/ana.23738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gunta SS, Thadhani RI, Mak RH. The effect of vitamin D status on risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9(6):337–347. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li YC, Kong J, Wei M, Chen ZF, Liu SQ, Cao LP. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(2):229–238. doi: 10.1172/JCI15219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li YC. Vitamin D regulation of the renin-angiotensin system. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88(2):327–331. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhou C, Lu F, Cao K, Xu D, Goltzman D, Miao D. Calcium-independent and 1,25(OH)2D3-dependent regulation of the renin-angiotensin system in 1alpha-hydroxylase knockout mice. Kidney Int. 2008;74(2):170–179. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Forman JP, Williams JS, Fisher ND. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and regulation of the renin-angiotensin system in humans. Hypertension. 2010;55(5):1283–1288. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.148619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sanna B, Brandt EB, Kaiser RA, et al. Modulatory calcineurin-interacting proteins 1 and 2 function as calcineurin facilitators in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(19):7327–7332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509340103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bodyak N, Ayus JC, Achinger S, et al. Activated vitamin D attenuates left ventricular abnormalities induced by dietary sodium in Dahl salt-sensitive animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(43):16810–16815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611202104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen S, Law CS, Grigsby CL, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of the vitamin D receptor gene results in cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2011;124(17):1838–1847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.032680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tarcin O, Yavuz DG, Ozben B, et al. Effect of vitamin D deficiency and replacement on endothelial function in asymptomatic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(10):4023–4030. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Caprio M, Mammi C, Rosano GM. Vitamin D: a novel player in endothelial function and dysfunction. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8(1):4–5. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.27271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2013 Sep 16; doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpt174. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aihara K, Azuma H, Akaike M, et al. Disruption of nuclear vitamin D receptor gene causes enhanced thrombogenicity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(34):35798–35802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Watson KE, Abrolat ML, Malone LL, et al. Active serum vitamin D levels are inversely correlated with coronary calcification. Circulation. 1997;96(6):1755–1760. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.de Boer IH, Kestenbaum B, Shoben AB, Michos ED, Sarnak MJ, Siscovick DS. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels inversely associate with risk for developing coronary artery calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(8):1805–1812. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bos D, Vernooij MW, Elias-Smale SE, et al. Atherosclerotic calcification relates to cognitive function and to brain changes on magnetic resonance imaging. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(Suppl 5):S104–S111. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yarchoan M, Xie SX, Kling MA, et al. Cerebrovascular atherosclerosis correlates with Alzheimer pathology in neurodegenerative dementias. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 12):3749–3756. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roher AE, Tyas SL, Maarouf CL, et al. Intracranial atherosclerosis as a contributing factor to Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(4):436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.08.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vidal JS, Sigurdsson S, Jonsdottir MK, et al. Coronary artery calcium, brain function and structure: the AGES-Reykjavik Study. Stroke. 2010;41(5):891–897. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.579581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Knopman D, Boland LL, Mosley T, et al. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2001;56(1):42–48. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Goldstein FC, Levey AI, Steenland NK. High blood pressure and cognitive decline in mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):67–73. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Hänninen T, et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and late-life mild cognitive impairment: A population-based study. Neurology. 2001;56(12):1683–1689. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reitz C, Tang MX, Manly J, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Hypertension and the risk of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(12):1734–1740. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.12.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Launer LJ, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, et al. Midlife blood pressure and dementia: the Honolulu-Asia aging study. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yamada M, Mimori Y, Kasagi F, Miyachi T, Ohshita T, Sasaki H. Incidence and risks of dementia in Japanese women: Radiation Effects Research Foundation Adult Health Study. J Neurol Sci. 2009;283(1–2):57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Qiu C, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The age-dependent relation of blood pressure to cognitive function and dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(8):487–499. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42(9):2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Petersen RC. Clinical Practice. Mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2227–2234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0910237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ganguli M, Snitz BE, Saxton JA, et al. Outcomes of mild cognitive impairment by definition: a population study. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(6):761–767. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Annweiler C, Schott AM, Berrut G, et al. Vitamin D and ageing: neurological issues. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(3):139–150. doi: 10.1159/000318570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Annweiler C, Allali G, Allain P, et al. Vitamin D and cognitive performance in adults: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(10):1083–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Grant WB. Does vitamin D reduce the risk of dementia? J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(1):151–159. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Etgen T, Sander D, Bickel H, Sander K, Förstl H. Vitamin D deficiency, cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33(5):297–305. doi: 10.1159/000339702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Llewellyn DJ, Langa KM, Lang IA. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;22(3):188–195. doi: 10.1177/0891988708327888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Balion C, Griffith LE, Strifler L, et al. Vitamin D, cognition, and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2012;79(13):1397–1405. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826c197f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Defina PA, Moser RS, Glenn M, Lichtenstein JD, Fellus J. Alzheimer’s disease clinical and research update for health care practitioners. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:207178. doi: 10.1155/2013/207178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease International Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chui HC, Victoroff JI, Margolin D, Jagust W, Shankle R, Katzman R. Criteria for the diagnosis of ischemic vascular dementia proposed by the State of California Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers. Neurology. 1992;42(3 Pt 1):473–480. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Román GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43(2):250–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hachinski V. Vascular dementia: a radical redefinition. Dementia. 1994;5(3–4):130–132. doi: 10.1159/000106709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1–2):125–132. doi: 10.1159/000109998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Langbaum JB, Fleisher AS, Chen K, et al. Ushering in the study and treatment of preclinical Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(7):371–381. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wiesmann M, Kiliaan AJ, Claassen JA. Vascular aspects of cognitive impairment and dementia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013 Sep 11; doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.159. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Iadecola C. The overlap between neurodegenerative and vascular factors in the pathogenesis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(3):287–296. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Neuropathology Group Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Aging Study. Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS) Lancet. 2001;357(9251):169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.White L, Small BJ, Petrovitch H, et al. Recent clinical-pathologic research on the causes of dementia in late life: update from the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18(4):224–227. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Crane PK, et al. Pathological correlates of dementia in a longitudinal, population-based sample of aging. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(4):406–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes L, Boyle P, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of older persons with and without dementia from community versus clinic cohorts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18(3):691–701. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Esiri MM, Nagy Z, Smith MZ, Barnetson L, Smith AD. Cerebrovascular disease and threshold for dementia in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1999;354(9182):919–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA. 1997;277(10):813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2004;62(7):1148–1155. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118211.78503.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zekry D, Duyckaerts C, Belmin J, Geoffre C, Moulias R, Hauw JJ. Alzheimer’s disease and brain infarcts in the elderly. Agreement with neuropathology. J Neurol. 2002;249(11):1529–1534. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Buell JS, Dawson-Hughes B, Scott TM, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, dementia, and cerebrovascular pathology in elders receiving home services. Neurology. 2010;74(1):18–26. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181beecb7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Annweiler C, Fantino B, Le Gall D, Schott AM, Berrut G, Beauchet O. Severe vitamin D deficiency is associated with advanced-stage dementia in geriatric inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):169–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Annweiler C, Rolland Y, Schott AM, et al. Higher vitamin D dietary intake is associated with lower risk of alzheimer’s disease: a 7-year follow-up. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1205–1211. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Annweiler C, Llewellyn DJ, Beauchet O. Low serum vitamin D concentrations in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(3):659–674. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Barnard K, Colón-Emeric C. Extraskeletal effects of vitamin D in older adults: cardiovascular disease, mortality, mood, and cognition. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8(1):4–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Annweiler C, Montero-Odasso M, Llewellyn DJ, Richard-Devantoy S, Duque G, Beauchet O. Meta-analysis of memory and executive dysfunctions in relation to vitamin D. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37(1):147–171. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.van der Schaft J, Koek HL, Dijkstra E, Verhaar HJ, van der Schouw YT, Emmelot-Vonk MH. The association between vitamin D and cognition: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013 May 29; doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.05.004. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Langa KM, et al. Vitamin D and risk of cognitive decline in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1135–1141. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Slinin Y, Paudel ML, Taylor BC, et al. Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study Research Group 25-Hydroxyvitamin D levels and cognitive performance and decline in elderly men. Neurology. 2010;74(1):33–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c7197b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Slinin Y, Paudel M, Taylor BC, et al. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group Association between serum 25(OH) vitamin D and the risk of cognitive decline in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(10):1092–1098. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]