Abstract

This study assessed the efficacy, tolerability and safety of vortioxetine versus placebo in adults with recurrent major depressive disorder. This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study included 608 patients [Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score≥26 and Clinical Global Impression – Severity score≥4]. Patients were randomly assigned (1 : 1 : 1 : 1) to vortioxetine 15 mg/day, vortioxetine 20 mg/day, duloxetine 60 mg/day or placebo. The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in MADRS total score at week 8 (mixed model for repeated measurements). Key secondary endpoints were: MADRS responders; Clinical Global Impression – Improvement scale score; MADRS total score in patients with baseline Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale ≥20; remission (MADRS≤10); and Sheehan Disability Scale total score at week 8. On the primary efficacy endpoint, both vortioxetine doses were statistically significantly superior to placebo, with a mean difference to placebo (n=158) of −5.5 (vortioxetine 15 mg, P<0.0001, n=149) and −7.1 MADRS points (vortioxetine 20 mg, P<0.0001, n=151). Duloxetine (n=146) separated from placebo, thus validating the study. In all key secondary analyses, both vortioxetine doses were statistically significantly superior to placebo. Vortioxetine treatment was well tolerated; common adverse events (incidence≥5%) were nausea, headache, diarrhea, dry mouth and dizziness. No clinically relevant changes were seen in clinical safety laboratory values, weight, ECG or vital signs parameters. Vortioxetine was efficacious and well tolerated in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder.

Keywords: duloxetine, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, placebo controlled, recurrent major depressive disorder, Sheehan Disability Scale, vortioxetine

Introduction

The bis-arylsulfanyl amine compound vortioxetine (1-[2-(2,4-dimethyl-phenylsulfanyl)-phenyl]-piperazine-hydrobromide, Lu AA21004) is a novel multimodal antidepressant. It is thought to work through a combination of two pharmacological modes of action: direct modulation of receptor activity and inhibition of the serotonin (5-HT) transporter. In-vitro studies indicate that vortioxetine is a 5-HT3, 5-HT7 and 5-HT1D receptor antagonist, 5-HT1B receptor partial agonist, 5-HT1A receptor agonist and an inhibitor of the 5-HT transporter (Bang-Andersen et al., 2011; Westrich et al., 2012). In-vivo nonclinical studies have demonstrated that vortioxetine enhances levels of multiple neurotransmitters (5-HT, noradrenaline, dopamine, acetylcholine and histamine) in specific areas of the brain (Mørk et al., 2012).

The antidepressant efficacy of vortioxetine has been demonstrated or supported in doses up to 10 mg/day in placebo-controlled and active treatment-controlled short-term studies of 6–8 weeks duration in adult patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) aged 18–75 years (Alvarez et al., 2012; Baldwin et al., 2012; Henigsberg et al., 2012) or at least 65 years (Katona et al., 2012), and in relapse prevention in adults with MDD (Boulenger et al., 2012).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy, tolerability and safety of two fixed doses of vortioxetine (15 and 20 mg/day) versus placebo in adult patients with moderate-to-severe recurrent MDD. The primary endpoint was the change from baseline in Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery and Åsberg, 1979) total score as primary endpoint after 8 weeks of treatment. The study included duloxetine (60 mg/day) as an active reference. This study differs from previous studies in using doses of vortioxetine corresponding to a 5-HT transporter occupancy of greater than 80% (Areberg et al., 2012b). A greater involvement of all pharmacological targets and potentially a broader clinical profile are expected with vortioxetine doses higher than those used in previous clinical trials (Alvarez et al., 2012; Baldwin et al., 2012; Bidzan et al., 2012; Henigsberg et al., 2012; Jain et al., 2013; Mahableshwarkar et al., 2013).

Materials and methods

Study design

This double-blind, randomized, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled, active-referenced study included 608 randomized patients from 72 psychiatric inpatient and outpatient settings in 13 countries (Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Russia, Slovakia, South Africa, Sweden and the Ukraine) from May 2010 to September 2011. Advertisements were used to recruit patients in Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden and South Africa. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice (ICH, 1996) and the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association (WMA), 2008). Local research ethics committees approved the trial design, and eligible patients provided written informed consent before participating.

At baseline, eligible patients were randomized (1 : 1 : 1 : 1) to vortioxetine 15 mg/day, vortioxetine 20 mg/day, duloxetine 60 mg/day or placebo for the 8-week, double-blind treatment period. Patients in the vortioxetine groups received vortioxetine 10 mg/day in week 1 and 15 or 20 mg/day from weeks 2–8. Patients in the duloxetine group received duloxetine 30 mg/day in week 1 and 60 mg/day from weeks 2–8. Patients were seen weekly during the first 2 weeks of treatment and then every 2 weeks. Patients who withdrew were seen for a withdrawal visit as soon as possible and were offered a down-taper regimen, as specified below.

Study medication was given as capsules of identical appearance. Following randomization, patients were instructed to take one capsule per day, orally, preferably in the morning. Those who completed the 8-week, double-blind treatment period entered a 2-week, double-blind discontinuation period: patients treated with duloxetine 60 mg/day were down-tapered with duloxetine 30 mg/day (week 9) followed by placebo (week 10). Patients treated with vortioxetine were discontinued abruptly and received placebo; patients treated with placebo remained on placebo. Patients were contacted for a safety follow-up 4 weeks after completion or after withdrawal from the study. Patients who withdrew were offered 1 week of treatment with double-blind, down-taper medication. A small number of patients (n=71) continued into an open-label extension study (NCT00788034).

Main entry criteria

Patients aged at least 18 and up to 75 years, with a primary diagnosis of recurrent MDD according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2000), a current major depressive episode (MDE) of greater than 3 months’ duration with an MADRS total score of at least 26 and a Clinical Global Impression – Severity (CGI-S) (Guy, 1976) score of at least 4 at screening and baseline visits were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients who exhibited anxiety symptoms were allowed to participate in the study, unless they fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for a current anxiety disorder according to DSM-IV-TR criteria [assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Lecrubier et al., 1997)].

Patients were excluded if they had any current psychiatric disorder other than MDD as defined in the DSM-IV-TR, or a current or past history of a manic or hypomanic episode, schizophrenia or any other psychotic disorder, mental retardation, organic mental disorders or mental disorders due to a general medical condition, any current diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence as defined in DSM-IV-TR, the presence or history of a clinically significant neurological disorder, or any neurodegenerative disorder that might compromise their participation in the study.

Patients at serious risk of suicide, on the basis of the investigator’s clinical judgement, or those who had a score of at least 5 on item 10 of the MADRS scale (‘suicidal thoughts’) were excluded, as were those receiving formal psychological treatments; pregnant or breast-feeding women; those with current depressive symptoms considered by the investigator to have been resistant to two adequate antidepressant treatments of at least 6-week duration; those who had failed to respond to treatment with duloxetine, or who had proved hypersensitive to duloxetine; and those who had previously been exposed to vortioxetine. Patients were also excluded if they were taking disallowed concomitant medication, as described by Alvarez et al. (2012), as well as the antibiotics rifampicin and ciprofloxacin, although antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives (except metoprolol, carvedilol, timolol and Class 1C antiarrhythmics) and proton pump inhibitors (except omeprazole and cimetidine) were permitted. Episodic use of zolpidem, zopiclone or zaleplon for severe insomnia was allowed for a maximum of 2 days/week, but not the night before a study visit.

Patients were also excluded if they had a clinically significant unstable illness, a thyroid-stimulating hormone value outside the reference range, history of cancer in remission for less than 5 years, clinically significant abnormal vital signs as determined by the investigator, an abnormal ECG at screening considered by the investigator to be clinically significant, or a PR interval>250 ms, a QRS interval>130 ms or a QTcF interval>450 ms (for men) or >470 ms (for women).

Safety reasons for withdrawal from the study were defined using the criteria described in the study by Baldwin et al. (2012). In addition, patients with a QTcF interval greater than 500 ms confirmed by ECG within 2 weeks or alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase values outside predefined ranges were withdrawn. If adverse events (AEs) contributed to withdrawal, they were regarded as the primary reason for withdrawal.

Efficacy rating

Patients were assessed with the MADRS from baseline to week 8. At the screening visit, investigators were asked to provide a clinical justification of the score for each of the MADRS items. These data were reviewed centrally by clinical experts as part of the monitoring during the study. All the raters underwent formal training in the MADRS and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, and the scoring conventions for the CGI, the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) (Hamilton, 1959) and the Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms checklist (DESS) (Rosenbaum et al., 1998) to maximize inter-rater reliability. Only raters (with few exceptions the rater was a psychiatrist) who passed the qualification test were allowed to rate patients in this study.

The effect of vortioxetine (15 or 20 mg/day) versus placebo on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and satisfaction related to various areas of functioning was assessed at baseline and at completion using the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire – Short Form [Q-LES-Q (SF)] (Endicott et al., 1993) and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) (Sheehan et al., 1996). The Q-LES-Q (SF) is a patient-reported outcome measure designed to assess the degree of enjoyment and satisfaction experienced by patients in various areas of daily life. It contains 16 items, each of which is rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good). The SDS is a patient-reported outcome measure that comprises items designed to measure the extent to which the patient’s global functioning is impaired by depressive symptoms. The patient rates the extent to which his/her work, social life, leisure activities, and home life or family responsibilities are impaired by his/her symptoms on a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (no disability) to 10 (extreme disability).

Allocation to treatment

Eligible patients were assigned to double-blind treatment according to a randomization list that was computer generated by H. Lundbeck A/S. The details of the randomization series were contained in a set of sealed opaque envelopes. At each site, sequentially enrolled patients were assigned the lowest randomization number available in blocks of eight using an interactive voice/web response system. All investigators, trial personnel and patients were blinded to treatment assignment for the duration of the study. The randomization code was not broken for any patient during the study.

Analysis sets

Safety analyses were based on the all-patients-treated set (APTS), comprising all randomized patients who took at least one dose of study medication. Efficacy analyses were based on a modified intent-to-treat set – the full-analysis set (FAS) – comprising all patients in the APTS who had at least one valid postbaseline assessment of the primary efficacy variable (MADRS total score).

Power and sample size calculations

With 120 patients per treatment group and an SD of 9.5, the power to detect a true treatment effect of 3.5 points in the change from baseline to week 8 on the MADRS total score compared with placebo would be at least 85%, using a 5% level of significance (2.5% within each dose group). To account for an expected withdrawal rate of 20%, a total of 600 patients (150 patients per group) was planned for randomization. This study was not powered to detect differences between vortioxetine and duloxetine.

Endpoints and testing strategy

A statistical testing strategy was defined a priori and comprised the primary efficacy analysis, as well as the key secondary efficacy analyses. To adjust for multiplicity, the 15 and 20 mg doses of vortioxetine were tested separately versus placebo in the primary and key secondary efficacy analyses at a Bonferroni-corrected significance level of 0.05/2=0.025. The following sequence of hierarchically ordered primary and key secondary endpoints was used (difference between vortioxetine and placebo at week 8 in):

change from baseline in MADRS total score (primary);

response (defined as a ≥50% decrease from baseline in MADRS total score);

Clinical Global Impression – Improvement scale (CGI-I) score;

change from baseline in MADRS total score in patients with a baseline HAM-A total score of at least 20;

remission (defined as an MADRS total score≤10);

change from baseline in SDS total score.

As soon as a hypothesis was rejected (that is, when there was no statistically significant difference vs. placebo at the 0.025 level of significance within a dose of 15 or 20 mg), the testing procedure was stopped. For endpoints that occurred after the prespecified statistical testing procedure was stopped or that were outside the testing procedure, nominal P-values with no adjustment for multiplicity were reported. The phrasing ‘separation from placebo’ is used to describe findings with nominal P-values less than 0.05. Efficacy analyses that were not multiplicity-controlled were considered secondary. The principal statistical software used was SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). The model included all four treatments, but comparison with duloxetine was not considered, as the study was not designed to examine any differences between vortioxetine and duloxetine.

Analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint

For the analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint, a mixed model for repeated measurements (MMRM) of the change from baseline in MADRS total score was applied. On the basis of missing-at-random assumption, these analyses were performed on the FAS, using observed cases (OC). The model included the fixed categorical effects of treatment, site, visit and treatment-by-visit interaction, as well as the continuous, fixed covariates of baseline MADRS total score and baseline MADRS total score-by-visit interaction. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to model the within-patient errors. When possible, the estimation method was a restricted maximum likelihood-based approach, but in the case of infinite likelihoods, the maximum likelihood was used.

Analysis of key secondary efficacy endpoints

The analyses of the key secondary continuous endpoints (MADRS and SDS total scores and CGI-I score) were performed using the same methodology as for the primary efficacy analysis (FAS, MMRM). For analyses of the CGI-I, the baseline CGI-S score was used for adjustment. Response and remission were analysed using logistic regression with treatment as factor and the baseline score as a covariate [FAS, last observation carried forward (LOCF)]. Data for patients treated with duloxetine were kept in the model to improve precision. Standard P-values were from χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests.

Safety and tolerability assessments

At each visit, starting at baseline, patients were asked a nonleading question (such as ‘How do you feel?’). All AEs either observed by the investigator or reported spontaneously by the patient were recorded, together with vital signs. Qualified personnel coded AEs using the lowest-level term according to MedDRA, version 14.0 (MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities), 2011). The incidence of individual AEs was compared between treatment groups using Fisher’s exact test. Clinical safety laboratory tests, weight, BMI, ECGs and physical examination findings were also evaluated.

Exploratory analyses of sexual function were conducted using the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX) (McGahuey et al., 2000). The main analysis of the ASEX data was performed to assess the number of participants who were normal at baseline but developed sexual dysfunction during the study period. Sexual dysfunction was defined as an ASEX total score of at least 19, a score of at least 5 on any item or a score of at least 4 on any three items (Delgado et al., 2005). Analysis of ASEX data was performed by logistic regression using a model that included treatment, baseline sexual dysfunction status, baseline sexual dysfunction status by treatment interaction and baseline score. Potential relationships between study drug and suicidality were assessed using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2010). As a post-hoc analysis, the safety database was searched at the verbatim (investigator’s term) level for possible suicide-related AEs (Laughren, 2006).

The DESS checklist (Rosenbaum et al., 1998) was designed to evaluate possible effects of discontinuation of antidepressant therapy. It is a clinician-rated instrument that queries for signs and symptoms on a 43-item checklist to assess whether the event is discontinuation-emergent. A new or worsened event reported after discontinuation of therapy scores 1 point on the checklist, and the DESS total score is the sum of all positive scores on the checklist. The DESS was used for patients who completed 8 weeks of treatment, the all-patients-completed set (APCS). The change from week 8 (completion) in DESS total score was analysed at weeks 9 and 10 using a analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with treatment and site as factors and the DESS total score at week 8 as a covariate.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

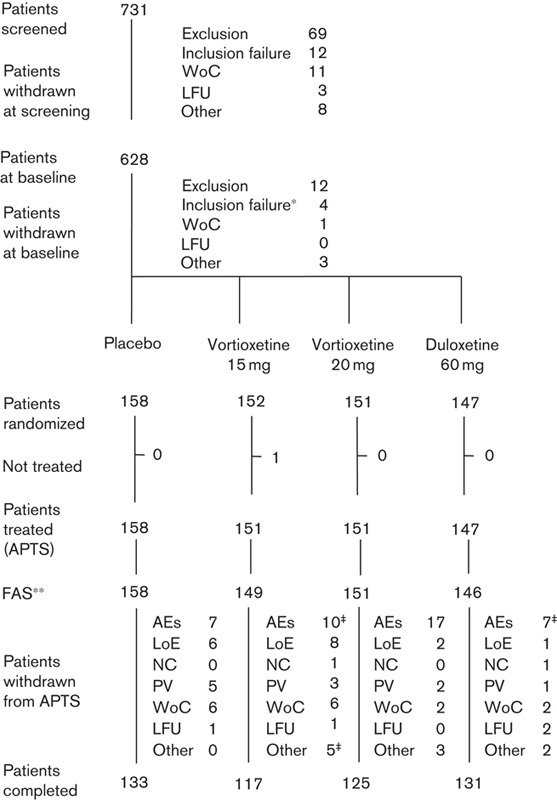

The APTS included 607 patients after the exclusion of one patient who did not take any study medication in the vortioxetine 15 mg group (Fig. 1). There were no clinically relevant differences between treatment groups in demographic or clinical characteristics at baseline (Table 1). Patients had a mean age of about 47 years, 66% were women and 98% were Caucasian.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patient disposition. AEs, adverse events; APTS, all-patients-treated set; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression – Severity; FAS, full-analysis set; LFU, lost to follow-up; LoE, lack of efficacy; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; NC, noncompliance; PV, protocol violation; WoC, patient consent withdrawn. *Three patients had a MADRS total score<26 and/or CGI-S score<4. **Patients with a valid postbaseline MADRS assessment. ‡Including one patient withdrawn from the FAS due to no postbaseline MADRS assessment.

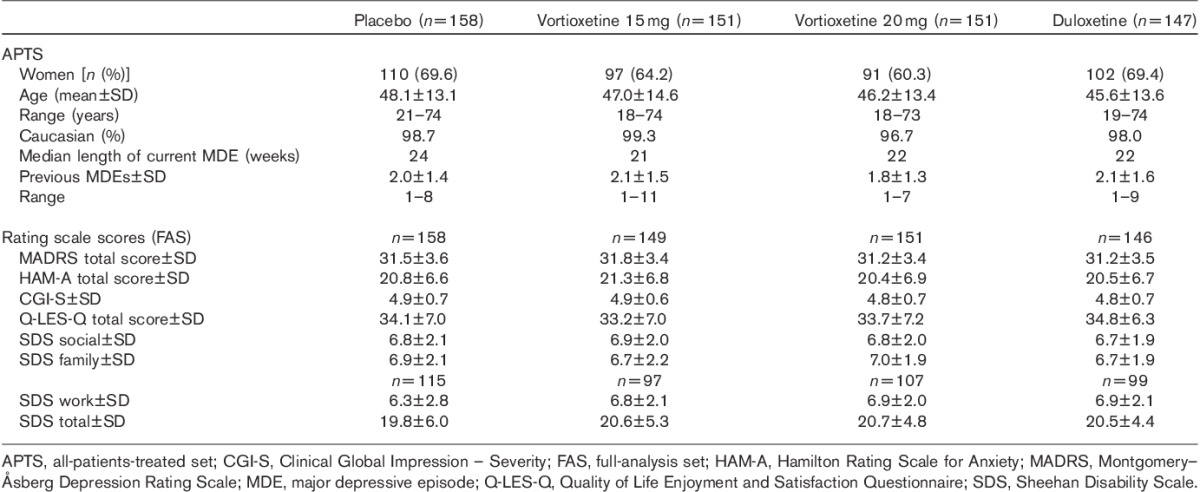

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

The mean baseline MADRS total score was 31.4±3.5, indicating moderate-to-severe depression, as also reflected in the mean CGI-S score of 4.8. All the patients had experienced a previous MDE, and the current episode had typically started about 6–7 months before enrolment (Table 1). Patients had a mean number of two previous MDEs and a median duration of 22 weeks (range 14–317 weeks) for the current MDE, and over half (51.2%) of the patients had one previous MDE, 24.5% had two and 24.3% had at least three previous MDEs. There was a substantial level of anxiety symptoms, indicated by a mean baseline HAM-A total score of 20.8.

Withdrawals from the study

The withdrawal rate due to all reasons during the entire study was 16.6% [15.8% (placebo), 22.5% (vortioxetine 15 mg), 17.2% (vortioxetine 20 mg) and 10.9% (duloxetine)] (Fig. 1). Overall, the most frequent primary reason for withdrawal was AEs (6.8%). There was no statistically significant difference to placebo in any of the active treatment groups in the proportion of patients who withdrew from the study. The percentage of patients who withdrew because of AEs was statistically significantly different only between vortioxetine 20 mg (11.3%) and placebo (4.4%). Analysis of time to withdrawal for any reason, or for lack of efficacy, showed no statistically significant differences in any of the treatment groups versus placebo. However, analysis of time to withdrawal due to AEs showed a statistically significantly shorter time to withdrawal in the vortioxetine 20 mg group than in the placebo group (Cox model; P=0.043). At least 83% of the patients in each treatment group received study medication for at least 43 days in the 8-week treatment period. The total exposure accrued in each treatment group was ∼21 patient years.

Efficacy

Primary efficacy endpoint

In the primary efficacy analysis, both doses of vortioxetine were statistically significantly superior to placebo in mean change from baseline in MADRS total score at week 8 (FAS, MMRM), with a mean treatment difference to placebo of −5.5 (vortioxetine 15 mg, SE=1.1, P<0.0001) and −7.1 points (vortioxetine 20 mg, SE=1.1, P<0.0001). The active reference duloxetine was also significantly superior to placebo (nominal P<0.0001), thus validating the study methodology and patient population.

There were no statistically significant main effects on the primary efficacy variable of any of the covariates (site, country, baseline MADRS and HAM-A total scores, sex, baseline weight, waist circumference, and age). Adjusting for these main effects did not change the estimates and conclusions on treatment differences. There was a statistically significant interaction between treatment and country (P=0.032). This was quantitative, with the size of effect varying per country as expected. None of the remaining covariates investigated interacted with treatment at the 5% level of significance.

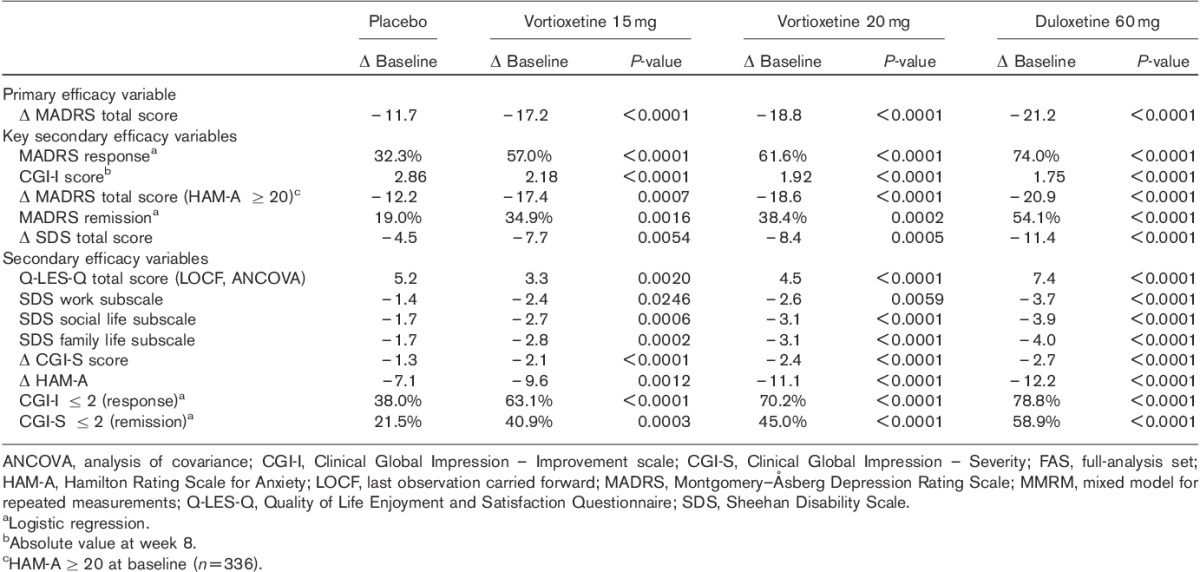

Key secondary efficacy endpoints

Both doses of vortioxetine were statistically significantly superior to placebo in all the predefined key secondary efficacy analyses, including response and remission based on the MADRS (Table 2). Response rates (≥50% decrease from baseline in MADRS total score, FAS, LOCF, logistic regression) were 32.3% (placebo), 57.0% (vortioxetine 15 mg) and 61.6% (vortioxetine 20 mg). Remission rates (MADRS total score≤10, FAS, LOCF, logistic regression) were 19.0% (placebo), 34.9% (vortioxetine 15 mg) and 38.4% (vortioxetine 20 mg).

Table 2.

Efficacy analyses, change from baseline to week 8 (FAS, MMRM)

For patients with a baseline HAM-A score of at least 20 [55.6% (336/604)], statistically significant superiority to placebo in mean change from baseline in MADRS total score at week 8 (FAS, MMRM) was seen, with a mean treatment difference to placebo of −5.2 (vortioxetine 15 mg, n=87, P=0.0007) and −6.4 (vortioxetine 20 mg, n=80, P<0.0001). Separation from placebo (nominal P<0.05) in mean MADRS scores was seen from week 4 onwards in all active treatment groups (FAS, MMRM).

The mean CGI-I score decreased (improved) throughout the 8-week treatment period to 2.2 (vortioxetine 15 mg), and 1.9 (vortioxetine 20 mg) at week 8 (FAS, MMRM). Separation from placebo (nominal P<0.05) was seen from week 2 onwards in the vortioxetine 20 mg group and from week 4 onwards in the vortioxetine 15 mg group (FAS, MMRM).

The SDS total scores were based on patients who were employed (placebo, n=115; vortioxetine 15 mg, n=97; vortioxetine 20 mg, n=107). The mean SDS total score decreased (improved) from ∼20 at baseline to 12 (vortioxetine 15 and 20 mg) at week 8. Separation from placebo (nominal P<0.05) was seen at weeks 6 and 8 in each of the active treatment groups (FAS, MMRM) (Table 2).

Secondary efficacy endpoints

Separation from placebo was seen from week 2 onwards (vortioxetine 20 mg) and week 4 onwards (vortioxetine 15 mg) and was maintained throughout the remainder of the treatment period (Fig. 2). To analyse the robustness of the results of the primary efficacy analysis, sensitivity analyses were performed. For both doses of vortioxetine, using ANCOVA (OC and LOCF), the difference to placebo was associated with a nominal P-value less than 0.0001. Separation from placebo (nominal P<0.01) was seen for all 10 MADRS single items at week 8 (FAS, MMRM) for each of the active treatment groups. The mean CGI-S score decreased (improved) throughout the 8-week treatment period from 4.8±0.7 at baseline to 2.6±1.2 (vortioxetine 15 mg, nominal P<0.0001 vs. placebo) and 2.4±1.2 (vortioxetine 20 mg, nominal P<0.0001 vs. placebo) at week 8 (FAS, LOCF). Separation from placebo (nominal P<0.05) was seen from week 2 onwards in the vortioxetine 20 mg group, and from week 4 onwards in the vortioxetine 15 mg group (FAS, MMRM).

Fig. 2.

Estimated Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total scores from baseline to week 8 (FAS, MMRM by visit) and LOCF (FAS, ANCOVA). Patient numbers at each visit are shown below the x-axis for each treatment group. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 versus placebo. ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; DUL, duloxetine; FAS, full-analysis set; LOCF, last observation carried forward; MMRM, mixed model, repeated measures; PBO, placebo.

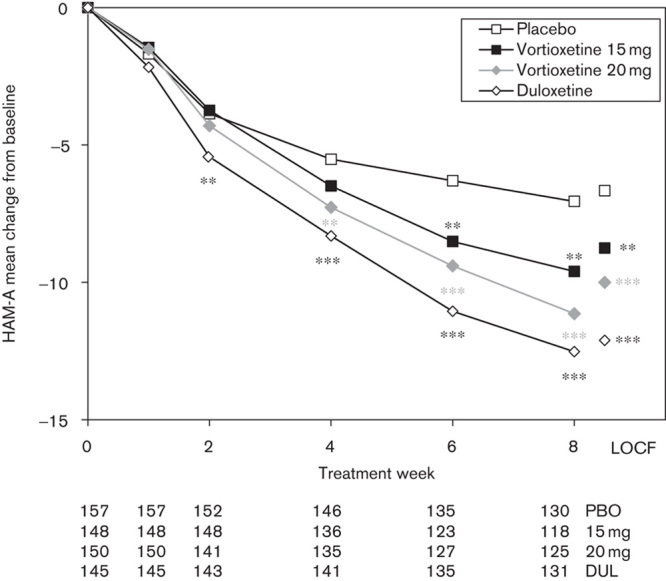

The mean HAM-A total score decreased (improved) from 20.8±6.7 at baseline in all the active treatment groups throughout the 8-week treatment period, with an adjusted mean change from baseline to week 8 of −9.6 (vortioxetine 15 mg, nominal P=0.0012 vs. placebo) and −11.1 (vortioxetine 20 mg, nominal P<0.0001 vs. placebo) (Fig. 3). The proportion of CGI-I responders (CGI-I ≤2) and CGI-S remitters (CGI-S ≤2) is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Estimated Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) total scores from baseline to week 8 (FAS, MMRM by visit) and LOCF (FAS, ANCOVA). Patient numbers at each visit are shown below the x-axis for each treatment group. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 versus placebo. ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; DUL, duloxetine; FAS, full-analysis set; LOCF, last observation carried forward; MMRM, mixed model, repeated measures; PBO, placebo.

Separation from placebo (nominal P<0.05) was seen for the SDS single-item scores at week 8 in each of the active treatment groups (FAS, MMRM) (Table 2). The mean Q-LES-Q total score increased (improved) in all the active treatment groups from ∼34 at baseline to 43 (vortioxetine 15 mg), and 44 (vortioxetine) at week 8. Separation from placebo (nominal P<0.01) was seen at week 8 in all active treatment groups (FAS, LOCF, ANCOVA). Item 16 scores (overall life satisfaction and contentment) increased from ∼2 at baseline to 3.0 (vortioxetine 15 mg), and 3.1 (vortioxetine 20 mg) at week 8. Separation from placebo (nominal P<0.01) was seen at week 8 in all active treatment groups (FAS, LOCF, ANCOVA).

Tolerability and safety

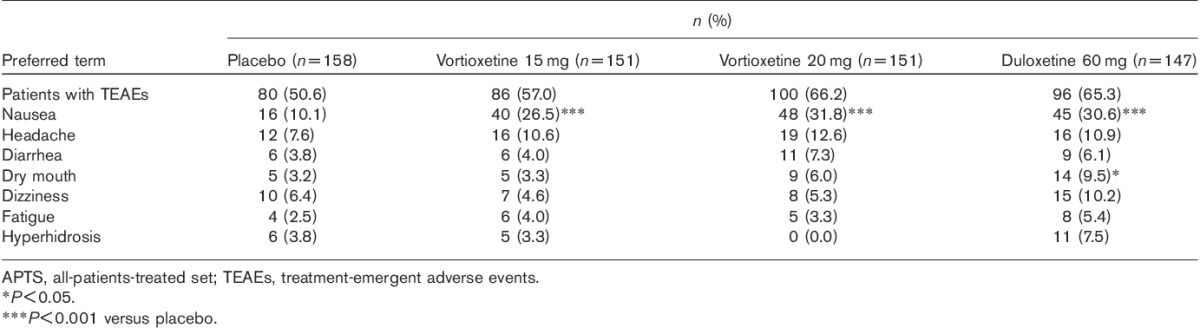

Adverse events

During the 8-week treatment period, approximately two-thirds of patients in the active treatment groups had one or more AEs (Table 3). During this period, 41 patients withdrew because of AEs (Fig. 1). The only AE leading to withdrawal of more than two patients in any of the treatment groups was nausea (3.3% in the vortioxetine 15 mg group, 6.6% in the vortioxetine 20 mg group and 2.0% in the duloxetine group).

Table 3.

Adverse events with an incidence of ≥5% in any treatment group in the 8-week treatment period (APTS)

The most common AEs reported by at least 5% of patients in either of the vortioxetine groups and for which the incidence was numerically higher than that in the placebo group were nausea, headache, diarrhea (20 mg) and dry mouth (20 mg). In the duloxetine group, AEs with an incidence of greater than 5% and higher in the placebo group were nausea, headache, dizziness, dry mouth, hyperhidrosis, diarrhea and fatigue. The incidence of AEs related to insomnia was low in all the treatment groups, ranging from 0% in the vortioxetine 15 mg group to 3% in the placebo and duloxetine groups.

The incidence of AEs related to sexual dysfunction (orgasm abnormal, anorgasmia, ejaculation delayed, ejaculation disorder, libido decreased, erectile dysfunction, orgasmic sensation decreased, sexual dysfunction) was 2.5% (placebo), 2.0% (vortioxetine 15 mg), 4.0% (vortioxetine 20 mg) and 3.5% (duloxetine) of patients. The mean ASEX total score remained at baseline level in all treatment groups throughout the 8-week treatment period (FAS, LOCF and OC). There were no statistically significant differences to placebo in any of the vortioxetine groups in ASEX total score at week 8 or any other week. There were no statistically significant differences to placebo in any of the active treatment groups in the proportion of patients without sexual dysfunction at baseline who developed sexual dysfunction any time during the 8-week treatment period. When the analysis was repeated for women and men separately, no statistically significant difference to placebo was seen in any of the active treatment groups. There were no significant changes from baseline in mean ASEX total scores in any of the treatment groups at week 8.

The incidence of AEs related to suicide and self-harm was low. Two patients took an intentional overdose of zolpidem (vortioxetine group) or zolpidem and lormetazepam (duloxetine group). Suicidal ideation was reported by 11.4% (placebo), 9.9% (vortioxetine 15 mg), 9.3% (vortioxetine 20 mg) and 6.1% (duloxetine) of patients. The C-SSRS data showed no clinically relevant differences between treatment groups at screening or during the study. An improvement in the scores for MADRS item 10 (suicidal thoughts) from baseline was seen in all treatment groups.

Serious AEs were reported by five patients: two patients in the vortioxetine 20 mg group and three patients in the duloxetine group. No serious AE was reported by more than one patient. No deaths occurred during this study. Two patients (one in each of the vortioxetine 20 mg and duloxetine groups) had serious AEs related to suicidal behaviour and self-harm.

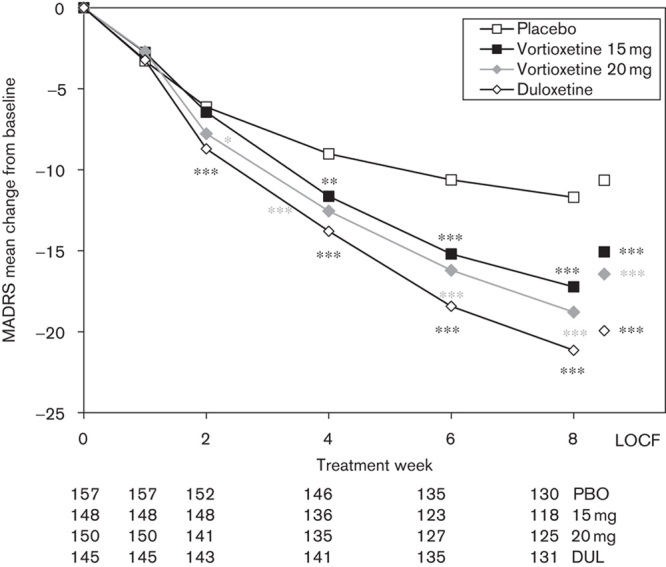

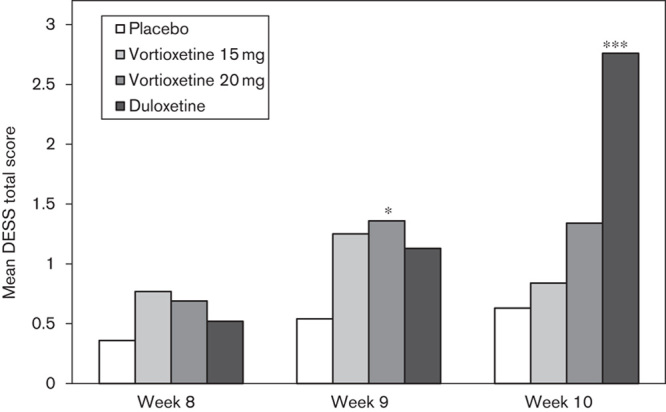

For patients who completed 8 weeks of treatment, the DESS was assessed at week 8 (baseline value) and at weeks 9 and 10. In the placebo group, the DESS total score increased from the baseline value of 0.4 to 0.5 points in the first week and 0.6 points in the second week of the discontinuation period (Fig. 4). Patients in the vortioxetine groups were abruptly switched to placebo at completion. In the vortioxetine 15 mg group, the DESS total score increased from the baseline value of 0.8 to 1.3 points in the first week and decreased to 0.8 points in the second week. In the vortioxetine 20 mg group, the DESS total score increased from the baseline value of 0.7 to 1.4 points in the first week (week 9) (P=0.0297) and to 1.3 points in the second week (week 10) (P=0.1690). Patients in the duloxetine group were down-tapered to 30 mg/day in the first week of the discontinuation period and switched to placebo in the second week. In the duloxetine group, the DESS total score increased from the baseline value of 0.5 to 1.1 points in the first week and to 2.8 points (P<0.0001) after the switch to placebo during the second week. In the second week of the discontinuation period, the DESS single items for which at least 10% of the patients in the treatment groups had reported either new symptoms or a worsening of pre-existing symptoms compared with week 8 comprised increased dreaming or nightmares (vortioxetine 15 mg) and dizziness/lightheadedness (vertigo), trouble sleeping, insomnia, irritability, fatigue/tiredness, nervousness or anxiety, bouts of crying/tearfulness, headache, agitation, mood swings and sudden worsening of mood (duloxetine).

Fig. 4.

Mean Discontinuation-Emergent Signs And Symptoms (DESS) total score at baseline (week 8), at 1 week (week 9) and 2 weeks (week 10) after tapered discontinuation of treatment (APCS, OC, ANCOVA). *P<0.05; ***P<0.001 versus placebo. ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; APCS, all-patients-completed set; OC, observed cases.

No clinically relevant changes over time or differences between treatment groups were seen in clinical laboratory test results, vital signs, weight or ECG parameters.

Discussion

This study evaluated the efficacy, safety and tolerability of two fixed doses of vortioxetine compared with placebo after 8 weeks of treatment in patients with MDD. In this study, duloxetine, an SNRI antidepressant, was included as an active reference. Preclinical data have shown that vortioxetine’s mode of action has two main components: a direct modulation of several 5-HT receptor subtypes (5-HT3, 5-HT7 and 5-HT1D receptor antagonism, 5-HT1B receptor partial agonism and 5-HT1A receptor agonism) and 5-HT reuptake inhibition (Pehrson et al., 2012; Westrich et al., 2012). Vortioxetine increases brain levels of 5-HT, dopamine and noradrenaline in brain areas implicated in the regulation of emotions, that is medial prefrontal cortex, ventral hippocampus and nucleus accumbens, at doses active in behavioural models predictive of antidepressant and anxiolytic activity (Mørk et al., 2012). The results of five randomized clinical trials of vortioxetine in the acute treatment of MDD have been published to date; they used doses ranging from 1 to 10 mg/day. Apart from one failed and one negative placebo-controlled study, both conducted in the USA using vortioxetine 5 mg/day (Jain et al., 2013; Mahableshwarkar et al., 2013), three studies demonstrated a significant antidepressant activity of daily doses of 5 and 10 mg in adults and the elderly (Alvarez et al., 2012; Henigsberg et al., 2012; Katona et al., 2012) and one failed study was supportive of these doses (Baldwin et al., 2012). In all of these clinical trials, the withdrawal rate because of AEs was between 3 and 11% for vortioxetine compared with 1 and 8% for placebo. Vortioxetine was judged to be well tolerated, with nausea being the only AE with an incidence of more than 10%. Two long-term studies – an open-label extension study demonstrating the effectiveness of vortioxetine as maintenance therapy (Baldwin et al., 2012) and a relapse prevention study (Boulenger et al., 2012) – have supported the favourable safety and tolerability profile as well as the antidepressant activity of 5 and 10 mg vortioxetine. Thus, vortioxetine has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in both the short-term and long-term treatment of MDD.

The in-vitro pharmacological profile and in-vivo receptor and 5-HT transporter occupancies of vortioxetine coupled with neuronal firing and microdialysis studies suggest that the targets of vortioxetine interact in a complex fashion, leading to dose-dependent modulation of neurotransmission in several systems, including the 5-HT, norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine and acetylcholine systems within the rat forebrain. In addition, a relationship between dose and 5-HT transporter occupancy has been shown by human PET studies (Areberg et al., 2012b), predicting a greater involvement of the 5-HT receptors and of the 5-HT transporter with increasing doses of vortioxetine.

In the present placebo-controlled study, doses of 15 and 20 mg were used for 8 weeks for the treatment of patients with MDEs fulfilling DSM-IV criteria for more than 3 months and presenting an initial MADRS total score of at least 26. On the prespecified primary efficacy endpoint, the superiority of both doses of vortioxetine to placebo was highly statistically significant, with a significant mean treatment difference in MADRS total scores at 8 weeks of 5.5 points with 15 mg and 7.1 points with 20 mg. Such a difference, much greater than the two-point average for approved antidepressants (Montgomery and Möller, 2009) and the 3 points recognized by NICE as clinically significant (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2004), is quite unusual in randomized controlled trials of antidepressants. These differences to placebo correspond to standardized effect sizes of 0.65 (15 mg) and 0.82 (20 mg). Clinical relevance is further shown by the proportions of responders and remitters and by the improvement in CGI-I score. As the difference to placebo of antidepressant medication increases with increasing baseline depression severity (Fournier et al., 2010), it cannot be ruled out that the high effect size is in part due to the inclusion of only patients with a baseline MADRS of at least 26. Differences in response rates compared with placebo (29.3 percentage points with 20 mg and 24.7 percentage points with 15 mg) were superior to the average 16 percentage points observed for antidepressants approved by the competent European authorities (Melander et al., 2008). The robustness of these results was confirmed by the statistically significantly better outcome than placebo observed in all the prespecified, multiplicity-corrected key secondary efficacy analyses. Previous studies evaluating vortioxetine in the treatment of MDD at 10 mg/day demonstrated statistically significant efficacy versus placebo (Alvarez et al., 2012; Henigsberg et al., 2012), with some indication of a dose–response effect, with numerically greater reductions at the higher dose levels. A similar trend was observed in the current study, with numerically greater improvement at the higher dose.

Vortioxetine showed an effect on anxiety symptoms over placebo, as demonstrated by a decrease of HAM-A total scores of 9.6 (15 mg) and 11.1 (20 mg) throughout the 8-week treatment period. The subgroup of patients with anxious depression, as defined with a baseline HAM-A score of at least 20, demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in mean change from MADRS baseline scores with vortioxetine compared with placebo at week 8 (15 mg: 5.2; 20 mg: 6.4). Improving depressive symptoms in patients with higher baseline anxiety may be particularly clinically meaningful, as these patients may be slower to respond to treatment and have lower rates of response to antidepressants (Fava et al., 2008). The anxiolytic efficacy of vortioxetine in these patients is consistent with the results of recent studies suggesting its efficacy in both short-term (Bidzan et al., 2012) and long-term treatment (Baldwin et al., 2012) of generalized anxiety disorder.

Treatment of depression still remains a challenge, with one of the issues being the diversity of the individual patient symptom profiles, and often residual symptoms persist at the end of antidepressant treatment (Nierenberg et al., 1999). In the present study vortioxetine had a favourable effect on a broad range of depressive symptoms, as demonstrated by a statistically significant decrease in all 10 MADRS single items throughout the 8-week treatment period, suggesting that vortioxetine may offer therapeutic benefit in reducing overall residual symptomatology.

Depression is associated with impairment of HRQoL and overall functioning, and therefore assessment of these during treatment is clinically relevant to both clinicians and patients (Wells et al., 1989; Trivedi et al., 2006). Unmet medical needs include antidepressant treatments that allow patients to recover to an extent that restores their ability to work and function in daily life, so that the burden on patient, the patient’s family and society as a whole can be reduced (Lam et al., 2011). Vortioxetine had a favourable effect on patient-reported overall functioning, as assessed using the SDS. Statistically significant efficacy was found for both vortioxetine doses in improving patients’ functioning, on the basis of the SDS total score, with standardized effect sizes of 0.47 (15 mg) and 0.55 (20 mg), and the social, family and work single-item scores. Moreover, both vortioxetine doses demonstrated a significant improvement in patient-reported HRQoL, based on the Q-LES-Q(SF) total score and the score for the item addressing overall life satisfaction and contentment. The standardized effect sizes were 0.38 (15 mg) and 0.52 (20 mg) for the Q-LES-Q(SF) total score and 0.36 (15 mg) and 0.42 (20 mg) for the item addressing overall life satisfaction and contentment. The clinical relevance of the results is supported by the magnitude of the standardized effect sizes, which exceed the minimal clinically important difference of 0.2 (Brozek et al., 2006).

As this study assesses the higher dose range of vortioxetine in the treatment of MDD, safety and tolerability data are summarized in some detail below. During this study, the withdrawal rate due to all reasons was 16.6% and there was no statistically significant difference compared with placebo in any of the active treatment groups; however, a statistically significant difference in the rate of withdrawal for AEs was found between vortioxetine 20 mg (11.3%) and placebo (4.4%). The rate of withdrawal because of AEs with vortioxetine 15 mg (6.8%) was similar to the rates reported in previous studies using vortioxetine doses up to 10 mg, that is 3–9%. The most common AE reported for vortioxetine was nausea; headache, diarrhea and dry mouth were also reported more frequently than with placebo, but not significantly so. The emergence of suicidal ideation during the study was lower in the active treatment groups than in the placebo group and the C-SSRS data showed no clinically relevant differences in suicidal ideation and behaviour between groups during this period. The incidence of AEs related to insomnia and sexual dysfunction was low and the ASEX total score remained at baseline levels in all treatment groups. Although sexual side effects are frequently reported during antidepressant treatment with SSRIs and SNRIs (Baldwin, 2004), their incidence with vortioxetine did not differ significantly from that observed with placebo in all the randomized clinical trials published so far, including one where vortioxetine was administered for up to 64 weeks (Boulenger et al., 2012). No consistent trend was observed for vital signs, weight, clinical values or ECG parameters in the active treatment groups and there were no marked differences to the patients receiving placebo. The DESS total score after abrupt discontinuation of vortioxetine treatment was low and similar to that of placebo. In the duloxetine group, in which patients were down-tapered during the first week, the DESS total score increased in the second week to twice that in the first week. Overall, abrupt discontinuation of vortioxetine was well tolerated and the low DESS total score and the nature of the discontinuation symptoms suggest that down-tapering of vortioxetine is not needed. This might be because of its relatively long apparent half-life of 66 h (Areberg et al., 2012a).

As in most clinical trials, the generalizability of this study is limited by the exclusion of patients with psychiatric or medical comorbidity and of those with marked suicidal ideation. To mitigate the risk of including ineligible patients in this study, first-episode patients were excluded and the duration of the depressive episode required for inclusion was 3 months or longer.

Conclusion

The present study reports the use of 15 or 20 mg doses of vortioxetine in the treatment of MDD. Both vortioxetine doses, as well as duloxetine 60 mg (used as the active reference), demonstrated a statistically significant effect on the primary and all key secondary efficacy criteria in prespecified testing sequence. Both doses of vortioxetine were well tolerated, with nausea and headaches being the AEs with the highest incidence.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients for their participation in the study. The authors gratefully acknowledge the participation of the following investigators in the psychiatric sites in the trial: Belgium: Joseph Lejeune, Leo Ruelens; Estonia: Kairi Mägi, Ellen Grüntal-Oja; Finland: Riitta Jokinen, Antti Ahokas, Ulla Lepola, Anna Savela, Markku Timonen, Hannu Koponen, Marko Sorvaniemi; France: Francis Gheysen, Joël Pon, Thierry Loiseau, Charles-Siegfried Peretti, Marcel Zins-Ritter, Jöel Gailledreau, Paule Khalifa, Mocrane Abbar, Eric Neuman; Germany: Klaus-Ulrich Oehler, Klaus Sallach, Alexander Schulze, Cornelia Drubig, Hans Martin Kolbinger, Peter Franz, Jana Thomsen; Latvia: Linda Keruze, Aisma Bredovska, Ilona Paegle, Andris Arajs, Strolis Imants; Lithuania: Daiva Deltuviene, Dalia Peciukaitiene, Sonata Rudzianskiene; Norway: Torbjørn Tvedten, Sverre Tønseth; Russia: Vladimir A Tochilov, Anna V Vasilieva, Alexander P Kotsubinskyi, Natalia V Dobrovolskaya, Isaak Y Gurovich, Julia B Barylnik, Alexander F Parashchenko, Andrey V Gribanov, Vitaliy A Tadtaev, Anatoliy B Bogdanov; Slovakia: Jana Grešková, Monika Biačková, Eva Janíková, Viera Kořínková, Peter Molčan, Abdul Mohammad Shinwari; South Africa: Greta Brink, Hilda Russouw; Sweden: Maj-Liz Persson, Kurt Wahlstedt, Per Ekdahl, Frank Hoyles; Ukraine: Volodymyr Abramov, Yuliya Blazhevych, Viktoriya Verbenko, Nataliya Maruta, Vladyslav Demchenko, Oksana Serebrennikova, Pavlo Palamarchuk, Gennadiy Zilberblat, Viktor Kovalenko, Andrey Skripnikov, Olena Venger, Iryna Spirina. The authors also thank D. J. Simpson (H. Lundbeck A/S) for providing support in the preparation, revision and editing of the manuscript.

H. Lundbeck A/S sponsored the study as part of a joint clinical development programme with the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. Lundbeck was involved in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflicts of interest

J.-P.B. has received grant funding from Lundbeck as well as honoraria and consultancy fees from Lundbeck, Sanofi, Astra-Zeneca and Servier. H.L. and C.K.O. are employees of Lundbeck.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: This study has the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01140906.

References

- Alvarez E, Perez V, Dragheim M, Loft H, Artigas F.A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, active-reference study of Lu AA21004 in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012;15:589–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) 2000:4th ed.Washington DC:American Psychiatric Association [Google Scholar]

- Areberg J, Chen G, Naik H, Pedersen KB, Vakilynejad M.A population pharmacokinetic meta-analysis of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in healthy subjects.Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2012a;16Suppl 115 [Google Scholar]

- Areberg J, Luntang-Jensen M, Søgaard B, Nilausen DO.Occupancy of the serotonin transporter after administration of Lu AA21004 and its relation to plasma concentration in healthy subjects.Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2012b;110:401–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DS.Sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant drugs.Expert Opin Drug Saf 2004;3:457–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DS, Loft H, Dragheim M.A randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study of three dosages of Lu AA21004 in acute treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD).Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2012;22:482–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang-Andersen B, Ruhland T, Jørgensen M, Smith G, Frederiksen K, Mørk A, et al. Discovery of 1-[2-(2,4-dimethylphenylsulfanyl)phenyl]piperazine (Lu AA21004): a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder.J Med Chem 2011;54:3206–3221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidzan L, Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen P, Yan M, Sheehan DV.Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in generalized anxiety disorder: results of an 8-week, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2012;22:847–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulenger JP, Loft H, Florea I.A randomized clinical study of Lu AA21004 in the prevention of relapse in patients with major depressive disorder.J Psychopharmacol 2012;26:1408–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozek JL, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ.How a well-grounded minimal important difference can enhance transparency of labelling claims and improve interpretation of a patient reported outcome measure.Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado PL, Brannan SK, Mallinckrodt CH, Tran PV, McNamara RK, Wang F, et al. Sexual functioning assessed in 4 double-blind placebo- and paroxetine-controlled trials of duloxetine for major depressive disorder.J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:686–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R.Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: a new measure.Psychopharmacol Bull 1993;29:321–326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, Balasubramani GK, Wisniewski SR, Carmin CN, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report.Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:342–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis.JAMA 2010;303:47–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W.ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Revised edition 1976Rockville, MD:National Institute of Mental Health [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M.The assessment of anxiety states by rating.Br J Med Psychol 1959;32:50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henigsberg N, Mahableshwarkar A, Jacobsen P, Chen Y, Thase ME.A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 8-week trial of the efficacy and tolerability of multiple doses of Lu AA21004 in adults with major depressive disorder.J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:953–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICH. 1996. Harmonised Tripartite Guideline E6: guideline for good clinical practice. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm073122.pdf [Accessed 10 July 2013]

- Jain R, Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen PL, Chen Y, Thase ME.A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 6-wk trial of the efficacy and tolerability of 5 mg vortioxetine in adults with major depressive disorder.Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;16:313–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK.A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder.Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;27:215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam RW, Filteau MJ, Milev R.Clinical effectiveness: the importance of psychosocial functioning outcomes.J Affect Disord 2011;132Suppl 1S9–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughren T. Memorandum on suicidality. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2006. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006-4272b1-01-fda.pdf [Accessed July 2013] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI.Eur Psychiatry 1997;12:224–231 [Google Scholar]

- Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen PL, Chen Y.A randomized, double-blind trial of 2.5 mg and 5 mg vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) versus placebo for 8 weeks in adults with major depressive disorder.Curr Med Res Opin 2013;29:217–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, Moreno FA, Delgado PL, McKnight KM, et al. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and validity.J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:25–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) 2011. What’s new for MedDRA version 14.0. Available at: http://www.meddramsso.com/files_acrobat/messenger/Messenger_Mar_2011.pdf [Accessed 10 July 2013] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Melander H, Salmonson T, Abadie E, van Zwieten-Boot B.A regulatory apologia – a review of placebo-controlled studies in regulatory submissions of new-generation antidepressants.Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2008;18:623–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery S, Åsberg M.A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change.Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:382–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Möller HJ.Is the significant superiority of escitalopram compared with other antidepressants clinically relevant?Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;24:111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mørk A, Pehrson A, Brennum LT, Nielsen SM, Zhong H, Lassen AB, et al. Pharmacological effects of Lu AA21004: a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder.J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012;340:666–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Depression: management of depression in primary and secondary care. National Clinical Practice Guideline 23 2004Great Britain:National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence;43 [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, Alpert JE, Pava JA, Worthington JJ, 3rd, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine.J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehrson A, Nielsen KGJ, Jensen JB, Sanchez C.The novel multimodal antidepressant Lu AA21004 improves memory performance in 5-HT depleted rats via 5-HT3 and 5-HT1A receptor mechanisms.Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2012;22Suppl 2S269 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Hoog SL, Ascroft RC, Krebs WB.Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial.Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA.The measurement of disability.Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;11Suppl 389–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Warden D, McKinney W, Downing M, et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among outpatients with major depressive disorder: a STAR*D report.J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for industry: suicidality: prospective assessment of occurrence in clinical trials. United States Food and Drug Administration; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burman MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study.JAMA 1989;262:914–919 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westrich L, Pehrson A, Zhong H, Nielsen SM, Frederiksen K, Stensbøl TB, et al. In vitro and in vivo effects of the multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) at human and rat targets.Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2012;16Suppl 147 [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association (WMA) 2008 Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/Accessed [Accessed 10 July 2013] [Google Scholar]