Abstract

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident protein kinase PERK is a major component of the unfolded protein response (UPR), which promotes the adaptation of cells to various forms of stress. PERK phosphorylates the α subunit of the translation initiation factor eIF2 at serine 51, a modification that plays a key role in the regulation of mRNA translation in stressed cells. Several studies have demonstrated that the PERK-eIF2α phosphorylation pathway maintains insulin biosynthesis and glucose homeostasis, facilitates tumor formation and decreases the efficacy of tumor treatment with chemotherapeutic drugs. Recently, a selective catalytic PERK inhibitor termed GSK2656157 has been developed with anti-tumor properties in mice. Herein, we provide evidence that inhibition of PERK activity by GSK2656157 does not always correlate with inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation. Also, GSK2656157 does not always mimic the biological effects of the genetic inactivation of PERK. Furthermore, cells treated with GSK2656157 increase eIF2α phosphorylation as a means to compensate for the loss of PERK. Using human tumor cells impaired in eIF2α phosphorylation, we demonstrate that GSK2656157 induces ER stress-mediated death suggesting that the drug acts independent of the inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation. We conclude that GSK2656157 might be a useful compound to dissect pathways that compensate for the loss of PERK and/or identify PERK pathways that are independent of eIF2α phosphorylation.

Keywords: translation initiation factor eIF2, PERK/PEK kinase, unfolded protein response, protein phosphorylation, mRNA translation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, tumorigenesis, pharmacological inhibitors

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is pivotal for the biosynthesis of secretory proteins and control of the capacity of the endocytotic system through a variety of post-translational modifications and chaperone events.1 Any imbalance between the load of proteins entering the ER and ER’s ability to process them activates an adaptive response that allows cells to respond to a variety of environmental or metabolic conditions.2 This response involves the coordinated expression of chaperones, enzymes, and other ER components, and is known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). The ultimate goal of UPR is to help cells survive the stress; however, under conditions of severe stress, UPR can become pro-apoptotic.1 UPR is initiated by the activation of 3 major pathways mediated by the ER-resident proteins inositol-requiring kinase 1 (IRE-1), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and the ER-resident kinase PERK/PEK.2 Increased UPR leads to expression of chaperones known as glucose-regulatory proteins (Grps), whose primary role is to adapt cells to ER stress.1 Several studies have indicated that UPR induction plays a crucial role in tumor growth.1,3 Also, UPR alters the sensitivity of tumors to chemotherapeutic drugs, making them resistant to certain drugs and sensitive to others, underscoring its importance in tumor treatment.3

Activated PERK phosphorylates the α subunit of the translation initiation factor eIF2 at serine 51, which leads to the global inhibition of protein synthesis as a means to decrease the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER.4 PERK is an important determinant of cell fate in UPR, because its short-term induction promotes cell survival through the induction of eIF2α phosphorylation, whereas its prolonged activation causes cell death.5,6 The biological effects of phosphorylated eIF2α are mediated, at least in part, through the preferential translation of specific mRNAs despite the general inhibition of protein synthesis.7 Such mRNAs encode proteins, like, for example, the activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), that facilitate the adaptation and promote the survival of stressed cells.8 Aberrant regulation of the PERK-eIF2α phosphorylation arm has been observed in several human diseases including diabetes, obesity, and cancer.9 That is, mutations of Perk gene were found in Wolcott–Rallison syndrome (WRS), a rare autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by permanent neonatal or early-infancy insulin-dependent diabetes.10 Activation of the PERK-eIF2α phosphorylation arm in UPR is mainly cytoprotective and helps cells to cope with oncogenic stress or stress in the tumor microenvironment.5,11-13 Furthermore, the PERK-eIF2α phosphorylation pathway is induced in tumor cells treated with chemotherapeutic drugs, leading to the development of drug resistance.13-15 The implications of PERK in tumorigenesis have raised the interesting hypothesis that its targeting may offer a novel therapeutic approach for cancers with increased UPR, including cancers of secretory nature or cancers with increased hypoxia.16 This has recently led to the development of novel PERK inhibitors by GlaxoSmithKline, which prevent the autophosphorylation of the kinase and eIF2α phosphorylation in mouse and human cells exposed to stress.16-18 Moreover, it was shown that a PERK inhibitor, termed GSK2656157, significantly decreased the growth of human tumor xenografts in mice.16 Equally important, GSK2606414, which is structurally similar to GSK2656157, has been recently shown to prevent neurodegeneration and clinical disease of prion-infected mice.19 These findings indicated the potential use of PERK inhibitors for the treatment of certain types of human diseases associated with deregulated UPR. Herein, we provide evidence that inhibition of PERK by GSK2656157 does not recapitulate the effects of genetic inactivation of PERK on eIF2α phosphorylation in stressed cells. Using human tumor cells impaired in eIF2α phosphorylation, we demonstrate that GSK2656157 promotes cell death in response to ER stress independent of inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation. Our data raise the possibility that the PERK inhibitors induce non-specific pathways, some of which interfere with the activity of other eIF2α kinases. The PERK inhibitors may be useful reagents to identify pathways that control stress responses of PERK that proceed independent of eIF2α phosphorylation.

Results and Discussion

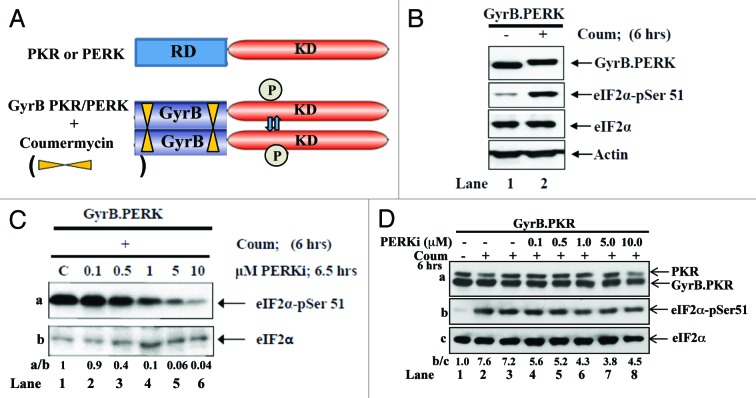

To examine GSK2656157 action, we employed a system which allows the conditional induction of eIF2α phosphorylation and relies on the expression of chimera proteins consisting of the N-terminal domain of the E.coli gyrase B (GyrB) fused to the kinase domain (KD) of either PKR or PERK (Fig. 1A).20,21 The GyrB.PERK and GyrB.PKR cDNAs were used to establish human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells stably expressing each chimera protein separately. Treatment of cells with the antibiotic coumermycin resulted in the activation of GyrB.PERK by autophosphorylation, as became evident by the shift in the electrophoretic migration of the chimera protein in polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 1B, lane 2). Coumermycin treatment also led to the induction of eIF2α phosphorylation at serine 51, which was detected by immunoblotting with phosphospecific antibodies (Fig. 1B, lane 2). When GyrB.PERK-expressing cells were treated with increasing concentrations of GSK2656157 in the presence of coumermycin, we observed that the PERK inhibitor decreased eIF2α phosphorylation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). When GyrB.PKR cells were used, we found that treatment with GSK2656157 did not have a similar robust effect on the inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation, as in GyrB.PERK-expressing cells (Fig. 1D). These data indicated that GSK2656157 is a potent and rather specific PERK inhibitor in cells ectopically expressing a conditionally active form of the eIF2α kinase.

Figure 1. Analysis of the effects of GSK2656157 on cells with conditionally active PERK or PKR. (A) Schematic representation of the GyrB system. The regulatory domain (RD) of either PKR (i.e., dsRNA-binding domain) or PERK (i.e., lumenal domain) was replaced by the GyrB domain, which was fused to the kinase domain (KD) of each eIF2α kinase. Coumermycin mediates the dimerization of the chimera kinase leading to its activation and induction of eIF2α phosphorylation. (B and C) GyrB.PERK cells were left untreated (B, lane 1) or treated with 100 ng/ml coumermycin for 6 h in the absence (B, lane 2; C, lane 1) or presence of the indicated concentrations of the PERK inhibitor (PERKi) (C, lanes 2–6). (D) GyrB.PKR cells were left untreated (lane 1) or treated with 100 ng/ml coumermycin for 6 h in the absence (lanes 2 and 3) or presence of the indicated concentrations of PERKi (lanes 4–8). (B–D) Cells extracts (50 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoblot analyses for the indicated proteins.

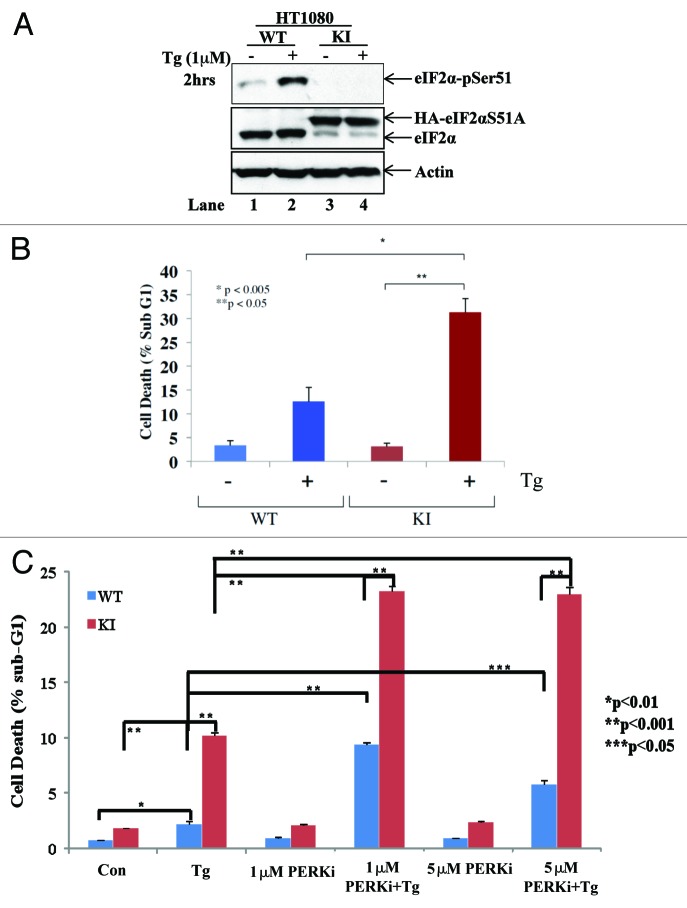

To determine the effect of GSK2656157 on endogenous PERK, HT1080 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the drug followed by short-term treatment with the ER stress inducer thapsigargin (TG). We observed that induction of eIF2α phosphorylation by TG treatment was impaired by GSK2656157 in all concentrations tested (Fig. 2A). However, when HT1080 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the PERK inhibitor for prolonged time in the absence of stress, we noticed a reduction of eIF2α phosphorylation at the 0.1 μM of the drug, which was not further reduced with increasing concentrations of the inhibitor (Fig. 2B). This finding indicated that either 0.1 μM of GSK2656157 was sufficient to block PERK activity, or PERK inactivation by the increased concentrations of the drug was compensated for by the activation of other eIF2α kinases.

Figure 2. Control of eIF2α phosphorylation by GSK2656157 in HT1080 cells. (A) Parental HT1080 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of PERKi in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1 μM thapsigargin (TG). As control untreated cells (lanes 1, 9, and 13) or cells treated 1 μM TG in the absence of PERKi (lanes 2, 10, and 14) were used. (B) Parental HT1080 cells were left untreated (lane 1) or treated with the indicated concentrations of the PERKi for 24 h (lanes 3–7). As control for eIF2α phosphorylation, cells were treated with 1 μM TG for 2 h (lane 2). (A and B) Cells extracts (50 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoblot analyses for the indicated proteins.

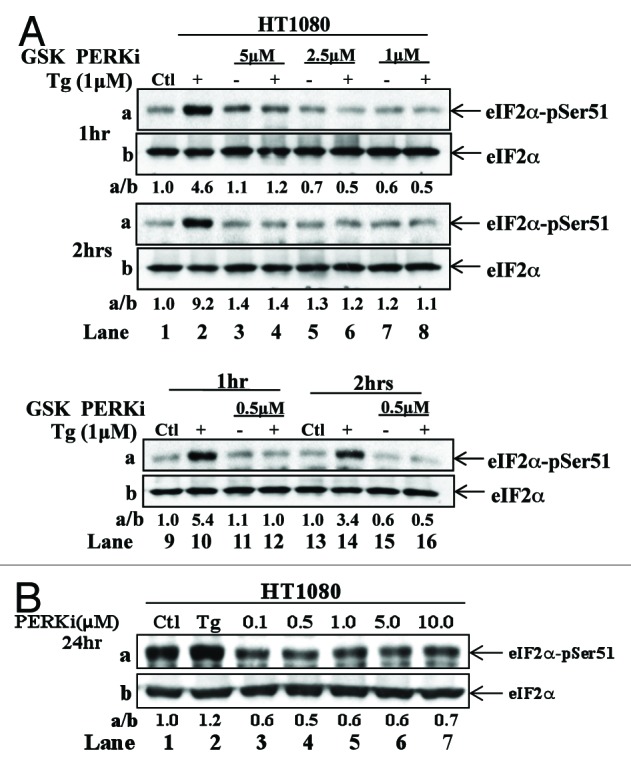

To distinguish between the 2 possibilities, we examined the properties of GSK2656157 in immortalized PERK+/+ and PERK−/− MEFs. First, we confirmed the suitability of the cells by detecting the loss of PERK and impaired eIF2α phosphorylation in PERK−/− MEFs in response to TG treatment (Fig. 3A). Then, we used PERK+/+ and PERK−/− MEFs for treatment with increasing concentrations of GSK2656157 followed TG treatment. We observed that the drug decreased PERK autophosphorylation at threonine (T)980 as became evident by immunoblotting with phosphospecific antibodies (Fig. 3B). We also noticed that inhibition of PERK T980 autophosphorylation was proportional to the concentration of the drug but was not associated with a linear decrease of eIF2α phosphorylation. This was because eIF2α phosphorylation was increased at 1 μM of the drug, a concentration that substantially suppressed PERK autophosphorylation (Fig. 3B, lanes 2–5). Moreover, we found that eIF2α phosphorylation was enhanced in PERK−/− MEFs incubated with increasing concentrations of the drug, up to 1 μM, above which eIF2α phosphorylation declined (Fig. 3B, lanes 9–14). We also tested the effects of GSK2656157 on PERK-mediated cell death in response to prolonged ER stress with TG treatment. We observed that the drug decreased the death of PERK+/+ MEFs at 1 μM to very similar levels of death seen with PERK−/− MEFs (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, increasing concentrations of the drug induced death in PERK−/− MEFs, indicating that these effects were exerted independent of PERK. Collectively, these data supported the notion that GSK2656157 causes the activation of another eIF2α kinase to compensate for the loss of PERK activity in cells. Also, the data suggested that GSK2656157 promotes death independent of PERK inhibition, particularly when it is used at increased concentrations.

Figure 3. Characterization of the biochemical properties of GSK2656157 in PERK+/+ and PERK−/− MEFs. (A) Immortalized PERK+/+ and PERK−/− MEFs were left untreated (lanes 1 and 3) or treated with 1 μM of TG for 2 h (lanes 2 and 4). (B) PERK+/+ and PERK−/− MEFs were left untreated (lanes 1 and 8) or treated with 1 μM of TG in the absence (lanes 2 and 9) or presence of the indicated concentrations of PERKi for 2 h (lanes 3–7 and 10–14). (A and B) Protein extracts (50 μg) were subjected to immunoblot analyses for the indicated proteins. (C) PERK+/+ and PERK−/− MEFs untreated (control) or treated with 1 μM TG in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of PERKi for 24 h. As control, cells treated with the indicated concentrations of PERKi in the absence of TG for 24 h. Cell death was measured by the percentage of cells in sub-G1 population by FACS analysis. Histograms represent the quantification of 3 independent experiments.

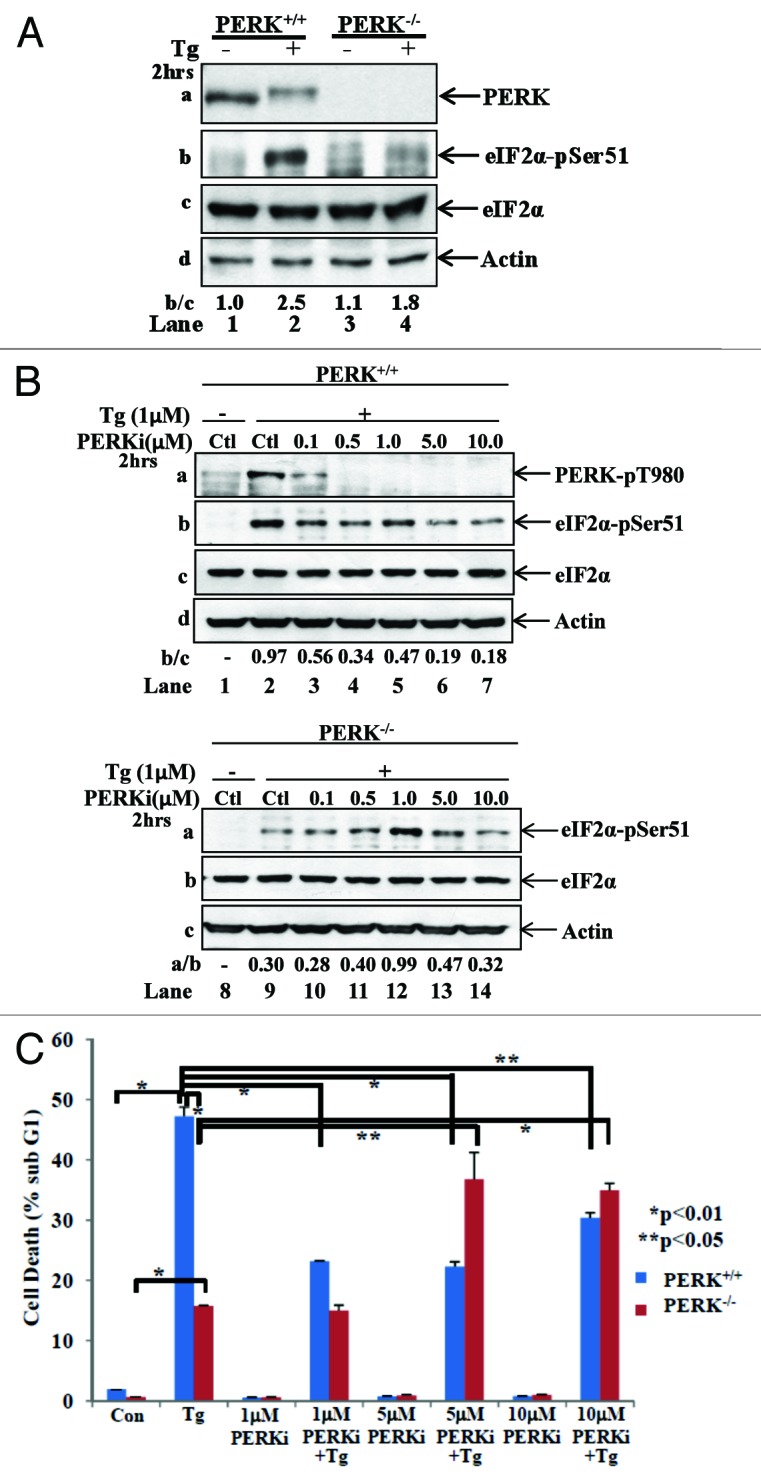

We also examined the biological effects of GSK2656157 on human tumor cells exposed to ER stress. Thus, we established HT1080 cells expressing an HA-tagged form of the non-phosphorylatable eIF2αS51A, under conditions of which expression of endogenous eIF2α was abolished by shRNA (herein referred to as knock-in [KI] cells). We observed that KI cells were defective in eIF2α phosphorylation as opposed to wild-type (WT) control cells in which eIF2α phosphorylation was substantially induced by TG treatment (Fig. 4A). We also observed that the loss of eIF2α phosphorylation rendered KI cells highly susceptible to death compared with WT cells in response to TG treatment (Fig. 4B). This finding is in line with previous data showing that mouse cells containing the S51A mutation in both eIF2α alleles were highly susceptible to ER stress-induced death compared with cells with intact eIF2α alleles.22 Considering that induction of eIF2α phosphorylation by PERK is a pro-survival event in response to ER stress,23 we wished to know whether treatment of tumor cells with GSK2656157 could further increase death by blocking the pro-survival function of the PERK-eIF2α phosphorylation arm in WT, but not in KI, cells. When HT1080 cells were treated with GSK2656157 at concentrations previously shown to inhibit tumor growth,16 we found that the PERK inhibitor similarly enhanced the amount of death in both WT and KI cells in response to TG treatment (Fig. 4C). This data indicated that GSK2656157 promotes cell death independent of inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation.

Figure 4. Characterization of the biological properties of GSK2656157 in tumor cells exposed to ER stress. (A) Cell extracts (50 μg of protein) from wild-type (WT) and knock-in (KI) HT1080 cells untreated or treated with 1 μM thapsigargin (TG) for 2 h were subjected to western blot analysis for the indicated proteins. Note the delayed migration of the HA-eIF2αS51A in knock-in (KI) cells (lanes 3 and 4) compared with endogenous eIF2α in wild-type (WT) cells (lanes 1 and 2). (B) HT1080 WT and KI cells were treated with 1 μM TG for either 24 h. (C) Cells were treated with 1 μM TG either in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of PERKi for 18 h. As control, cells were treated with the same concentrations of PERKi in the absence of TG for 18 h. (B and C) Cell death was assessed by the percentage of cells in sub-G1 population by FACS analysis. Histograms represent the quantification of 3 independent experiments.

Our data are in agreement with previous studies showing that the PERK inhibitors impair eIF2α phosphorylation in cells exposed to short-term ER stress.16,18 Because the biological effects of the drugs require prolonged treatments, our data are consistent with the interpretation that the anti-tumor as well as anti-neurodegenerative function of the PERK inhibitors may not be caused through the inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation.16,19 Interestingly, several studies have provided evidence that PERK can act independent of eIF2α phosphorylation. That is, our group demonstrated that PERK promotes the adaptation of cells to ER stress through its ability to disarm the pro-apoptotic function of the tumor suppressor p53. PERK does so via the activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), which leads to phosphorylation and Mdm2-dependent degradation of p53.24-27 Also, other studies provided evidence that the antioxidant functions of PERK may also be mediated independent of eIF2α phosphorylation through the activation of the transcription factor Nrf2.28 How the ATP-competitive inhibitors selectively inhibit some but not all of PERK functions is not known, but this effect could be related to the ability of the drugs to trap the kinase in an inactive conformation rather than inhibiting its phosphotransfer activity.17 Also, the drugs inhibit the activity of several other kinases at high concentrations,17 a property that could contribute to the induction of PERK-independent effects in response to ER stress. Furthermore, PERK may not be the dominant kinase that phosphorylates eIF2α in different tumor types, and as such, pharmacological inhibition of the kinase may not be sufficient to impair eIF2α phosphorylation because of compensation by other eIF2α kinases.13 In regard to anti-tumor therapies, our data imply that strategies aimed at the inhibition of PERK and other eIF2α kinases like GCN2, which also displays pro-survival functions,29 might be a better approach to disarm the pro-survival effects of phosphorylated eIF2α as a means to treat cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatments

The origin of immortalized PERK+/+ and PERK−/− MEFs was previously described.23 MEFs were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Wisent) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 1× of essential and non-essential amino acids (Gibco), and antibiotics (100 U/ml of penicillin-streptomycin; Gibco). HT1080 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. GSK2656157 was purchased from Vibrant Pharma (Cat No VPI-COA-610) and stored in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 10 mM.

Generation of HT1080 GyrB.PERK and KI cells

The GyrB.PERK cDNA was constructed by replacing the kinase domain (KD) sequence of PKR in pSG5-GyrB.PKR vector20 with the KD sequence of PERK.30 Cells were transfected with pSG5-GyrB.PERK and pcDNA3.1/Zeo vectors and selected in 200 μg/ml of zeocin (Invitrogen) as described.20 The generation of HT1080 KI cells was described elsewhere.31

Flow cytometry analysis

Cells were subjected to propidium iodide (PI) staining and FACScan analysis based on a previously described protocol.32 FACS was performed with BD FACScalibur and the data was analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc).

Western blot analysis

Protein extraction and immunoblotting were performed as described.32 The antibodies used were: rabbit monoclonal against phosphorylated eIF2α at S51 (Novus Biologicals), mouse monoclonal anti-eIF2α, and rabbit polyclonal anti-PERK T980 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology), mouse monoclonal antibody to PERK,14 mouse monoclonal antibody against actin (Clone C4, ICN Biomedicals Inc). All antibodies were used at a final concentration of 0.1–1 μg/ml. Following incubation with the indicated primary antibodies, membranes were probed with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidise (HRP) (Mandel Scientific). Proteins were visualized with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Thermo Scientific) detection system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of protein bands was performed by densitometry using Scion Image from the NIH.

Statistical analysis

Error bars represent standard error as indicated and significance in differences between arrays of data tested was determined using 2-tailed Student t test (Microsoft Excel).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to A.E.K. A.I.P. was recipient of the Doctoral Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canadian Graduate Scholarship from CIHR and an internal CIHR-funded McGill Chemical Biology post-doctoral award.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/27726

References

- 1.Schröder M, Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:739–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Y, Hendershot LM. The role of the unfolded protein response in tumour development: friend or foe? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:966–77. doi: 10.1038/nrc1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ron D. Translational control in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1383–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI16784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raven JF, Koromilas AE. PERK and PKR: old kinases learn new tricks. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1146–50. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.9.5811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:880–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ. All roads lead to ATF4. Dev Cell. 2003;4:442–4. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00100-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim I, Xu W, Reed JC. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:1013–30. doi: 10.1038/nrd2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delepine M, Nicolino M, Barrett T, Golamaully M, Lathrop GM, Julier C. EIF2AK3, encoding translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 3, is mutated in patients with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Nat Gene. 2000;25:406–9. doi: 10.1038/78085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wouters BG, Koritzinsky M. Hypoxia signalling through mTOR and the unfolded protein response in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:851–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye J, Koumenis C. ATF4, an ER stress and hypoxia-inducible transcription factor and its potential role in hypoxia tolerance and tumorigenesis. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:411–6. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koromilas AE, Mounir Z. Control of oncogenesis by eIF2α phosphorylation: implications in PTEN and PI3K-Akt signaling and tumor treatment. Future Oncol. 2013;9:1005–15. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mounir Z, Krishnamoorthy JL, Wang S, Papadopoulou B, Campbell S, Muller WJ, Hatzoglou M, Koromilas AE. Akt determines cell fate through inhibition of the PERK-eIF2α phosphorylation pathway. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra62. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusio-Kobialka M, Podszywalow-Bartnicka P, Peidis P, Glodkowska-Mrowka E, Wolanin K, Leszak G, Seferynska I, Stoklosa T, Koromilas AE, Piwocka K. The PERK-eIF2α phosphorylation arm is a pro-survival pathway of BCR-ABL signaling and confers resistance to imatinib treatment in chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:4069–78. doi: 10.4161/cc.22387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkins C, Liu Q, Minthorn E, Zhang SY, Figueroa DJ, Moss K, Stanley TB, Sanders B, Goetz A, Gaul N, et al. Characterization of a novel PERK kinase inhibitor with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1993–2002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Axten JM, Medina JR, Feng Y, Shu A, Romeril SP, Grant SW, Li WH, Heerding DA, Minthorn E, Mencken T, et al. Discovery of 7-methyl-5-(1-[3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]acetyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-5-yl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine (GSK2606414), a potent and selective first-in-class inhibitor of protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) J Med Chem. 2012;55:7193–207. doi: 10.1021/jm300713s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding HP, Zyryanova AF, Ron D. Uncoupling proteostasis and development in vitro with a small molecule inhibitor of the pancreatic endoplasmic reticulum kinase, PERK. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44338–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.428987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno JA, Halliday M, Molloy C, Radford H, Verity N, Axten JM, Ortori CA, Willis AE, Fischer PM, Barrett DA, et al. Oral treatment targeting the unfolded protein response prevents neurodegeneration and clinical disease in prion-infected mice. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kazemi S, Papadopoulou S, Li S, Su Q, Wang S, Yoshimura A, Matlashewski G, Dever TE, Koromilas AE. Control of alpha subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2 alpha) phosphorylation by the human papillomavirus type 18 E6 oncoprotein: implications for eIF2 alpha-dependent gene expression and cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3415–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3415-3429.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papadakis AI, Baltzis D, Buensuceso RC, Peidis P, Koromilas AE. Development of transgenic mice expressing a conditionally active form of the eIF2α kinase PKR. Genesis. 2011;49:743–9. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheuner D, Song B, McEwen E, Liu C, Laybutt R, Gillespie P, Saunders T, Bonner-Weir S, Kaufman RJ. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1165–76. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qu L, Huang S, Baltzis D, Rivas-Estilla AM, Pluquet O, Hatzoglou M, Koumenis C, Taya Y, Yoshimura A, Koromilas AE. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces p53 cytoplasmic localization and prevents p53-dependent apoptosis by a pathway involving glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. Genes Dev. 2004;18:261–77. doi: 10.1101/gad.1165804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pluquet O, Qu LK, Baltzis D, Koromilas AE. Endoplasmic reticulum stress accelerates p53 degradation by the cooperative actions of Hdm2 and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9392–405. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9392-9405.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baltzis D, Pluquet O, Papadakis AI, Kazemi S, Qu LK, Koromilas AE. The eIF2alpha kinases PERK and PKR activate glycogen synthase kinase 3 to promote the proteasomal degradation of p53. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31675–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qu L, Koromilas AE. Control of tumor suppressor p53 function by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:567–70. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cullinan SB, Diehl JA. Coordination of ER and oxidative stress signaling: the PERK/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:317–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye J, Kumanova M, Hart LS, Sloane K, Zhang H, De Panis DN, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Diehl JA, Ron D, Koumenis C. The GCN2-ATF4 pathway is critical for tumour cell survival and proliferation in response to nutrient deprivation. EMBO J. 2010;29:2082–96. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–4. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajesh K, Papadakis AI, Kazimierczak U, Peidis P, Wang S, Ferbeyre G, Kaufman RJ, Koromilas AE. eIF2α phosphorylation bypasses premature senescence caused by oxidative stress and pro-oxidant antitumor therapies. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5:884–901. doi: 10.18632/aging.100620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muaddi H, Majumder M, Peidis P, Papadakis AI, Holcik M, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Hatzoglou M, Koromilas AE. Phosphorylation of eIF2α at serine 51 is an important determinant of cell survival and adaptation to glucose deficiency. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3220–31. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]