Abstract

Enhancing the ability of either endogenous or transplanted oligodendrocyte progenitors (OPs) to engage in myelination may constitute a novel therapeutic approach to demyelinating diseases of the brain. It is known that in adults neural progenitors situated in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricle (SVZ) are capable of generating OPs which can migrate into white matter tracts such as the corpus callosum (CC). We observed that progenitor cells in the SVZ of adult mice expressed CXCR4 chemokine receptors and that the chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12 was expressed in the CC. We therefore investigated the role of chemokine signaling in regulating the migration of OPs into the CC following their transplantation into the lateral ventricle. We established OP cell cultures from Olig2-EGFP mouse brains. These cells expressed a variety of chemokine receptors, including CXCR4 receptors. Olig2-EGFP OPs differentiated into CNPase-expressing oligodendrocytes in culture. To study the migratory capacity of Olig2-EGFP OPs in vivo, we transplanted them into the lateral ventricles of mice. Donor cells migrated into the CC and differentiated into mature oligodendrocytes. This migration was enhanced in animals with Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE). Inhibition of CXCR4 receptor expression in OPs using shRNA inhibited the migration of transplanted OPs into the white matter suggesting that their directed migration is regulated by CXCR4 signaling. These findings indicate that CXCR4 mediated signaling is important in guiding the migration of transplanted OPs in the context of inflammatory demyelinating brain disease.

Keywords: Chemokine, chemokine receptor, chemoattraction, progenitor cell, multiple sclerosis, oligodendrocyte, white matter

Introduction

During the perinatal development of the brain large numbers of progenitors, originating in the subventricular zone (SVZ), migrate into the white matter and cortex where they differentiate into oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (Cayre et al., 2009; Menn et al., 2006; Parent et al., 2006). However, in the adult brain progenitors located in the SVZ mostly migrate along the rostral migratory stream (RMS) to form neurons in the olfactory bulb. Nevertheless, some adult SVZ progenitors are still capable of forming oligodendrocytes. Rather than migrating via the RMS, these progenitors migrate into the white matter. The number of SVZ neural progenitors that form oligodendrocytes in adult animals is low compared to the number that differentiate into olfactory neurons. However, under pathological conditions, such as in association with demyelination or seizures, endogenous OP proliferation in the SVZ is stimulated, OPs migrate in greater numbers and may also migrate to additional sites not observed in control animals (Cayre et al., 2009; Nait-Oumesmar et al., 2007). It has also been demonstrated that transplantation of cultured neural progenitors into the ventricles of normal mice, or into animals with experimentally induced demyelination, resulted in their migration into the white matter and differentiation into myelinating oligodendrocytes (Carbajal et al., 2010; Cayre et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2010; Windrem et al., 2004). However, the important factors that are responsible for directing the migration of OPs in the adult brain have not been identified.

Recent studies from several laboratories have demonstrated a key role for chemokines in regulating the migration of stem cells during the development of numerous tissues, including several structures in the nervous system (Bagri et al., 2002; Belmadani et al., 2005; Cayre et al., 2009; Klein and Rubin, 2004; Klein et al., 2001; Li and Ransohoff, 2008; Tran and Miller, 2003). Moreover, chemokines also control neural stem cell migration postnatally when these cells attempt to repair damage produced by brain diseases such as stroke (Ohab et al., 2006; Thored et al., 2006).

Chemokines are small, secreted proteins that were originally shown to play a central role in orchestrating inflammatory responses by guiding the migration and development of leukocytes. Chemokines produce all of their known effects through the activation of a family of G protein coupled receptors (Tran and Miller, 2003). We have previously demonstrated that neural progenitor cells from embryonic or postnatal brain express numerous types of chemokine receptors (Tran et al., 2007). In particular, the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand the chemokine SDF-1 are constitutively expressed in both developing and adult brain. Indeed, CXCR4 receptors are normally expressed at high levels by neural stem cells in the adult dentate gyrus (DG) and SVZ (Tran et al., 2007). Furthermore, signaling via the CXCR4 and CXCR2 chemokine receptors has been shown to be important in the original development of oligodendrocytes in the spinal cord (Dziembowska et al., 2005).

We therefore investigated whether CXCR4 signaling might be involved in regulating the migration of transplanted OPs into the adult brain. The results of our studies demonstrate that OPs transplanted into the lateral ventricles migrate into the white matter and that this migration is partially dependent on CXCR4 signaling.

Materials and methods

Animals

SJL animals were used for EAE induction. The following transgenic mice were also used in this study: CXCR4-EGFP and Olig2-EGFP (kindly provided by Dr Mary Beth Hatten and The Gene Expression Nervous System Atlas (GENSAT) project, NINDS contract N01NS02331 to the Rockefeller University, NY http://www.gensat.org/index.html). SDF-1-RFP/CXCR4-EGFP bitransgenic mice were made in our laboratory by generating SDF-1-RFP mice and crossing them with CXCR4-EGFP mice (Bhattacharyya et al., 2008). All of the procedures performed on animals within this study were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cultures of oligospheres

Mouse “oligospheres” are populations of mouse OPs cultured as free-floating aggregates. The culture method was adapted from (Vitry et al., 1999). Cerebral hemispheres of postnatal (P0-P3) mice were minced in Hanks' buffer (supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.15% sodium bicarbonate, and 10 mM Hepes buffer) and digested for 20 min at 37°C with trypsin. Digested tissues were mechanically dissociated by serial titration using 21 and 22.5 gauge needles. Dissociated cells were centrifuged, resuspended in Hanks' supplemented buffer, and layered on a preformed Percoll gradient then centrifuged at 16000×g for 40 min. The fraction containing glial progenitors localized between the myelin and red blood cell fractions was then recovered. After washing twice in Hanks', cells were resuspended in Hanks' supplemented buffer with 5% FCS. After differential adhesion on plastic culture dishes, non-adherent cells were recovered and resuspended in fresh feeding medium composed of DMEM (supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 g/ml glucose and non-essential amino acids) and N1 supplements (Sigma). This DMEM-N1 medium was supplemented with B104 neuroblastoma conditioned medium (N1-B104) in a 70:30 ratio. In addition, bFGF (10 ng/ml), PDGF (10 ng/ml) and heparin were added prior to use. Twenty-four hours after purification, floating oligospheres were recovered and resuspended in fresh feeding medium before plating onto untreated plastic flasks.

To induce in vitro differentiation, oligospheres maintained for 5 days in N1-B104 were seeded onto glass coverslips pre-coated with poly-D-lysine. The spheres were allowed to adhere for 1 hr before changing the medium to differentiation medium composed of DMEM-N1 medium supplemented with 2% FCS. Spheres were allowed to differentiate for 72 hrs and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) before immunolabeling.

For injection into EAE mice, oligospheres were infected with an adenovirus if needed. After 3-4 days in culture, oligospheres were dissociated.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from oligosphere cultures using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) and treated with RNase-free DNase to eliminate genomic DNA. cDNA was obtained from 5 μg of total RNA using SuperscriptII Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies) and was primed with 50 ng oligo(dT) oligonucleotide (PCR primers for chemokine receptors are shown in Table 1). After heating at 96°C for 5 min, PCR amplification was carried out for 35 cycles: 96°C for 30 sec, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and PCR was carried out using Taq polymerase (Life Technologies). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a positive control.

Table 1. RT-PCR Primers.

| Name | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| CCR1 | Forward | 5′-ATG GAG ATT TCA GAT TTC ACA GAA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGC TAC AGG TAC GGT GAG TGA ACT-3′ | |

| CCR2 | Forward | 5′-ATG TTA CCT CAG TTC ATC CAC GGC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTA ATG GTG ATC ATC TTG TTT GGA-3′ | |

| CCR3 | Forward | 5′-ATG GCA TTC AAC ACA GAT GAA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTC ACA GTT CGG GCT CGA AGG-3′ | |

| CCR4 | Forward | 5′-ATG AAT GCC ACA GAG GTC ACA GAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ACC AGG TAC ATC CAT GAA ACG ATC-3′ | |

| CCR5 | Forward | 5′-TCA GTT CCG ACC TAT ATC TAT G-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTG GAA AAT GAG GAC TGC ATG T-3′ | |

| CCR6 | Forward | 5′-TAG GAC TGG AGC CTG GAT AAC CAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TAG GGC TTG AGA TGA TGA TGG AGA-3′ | |

| CCR7 | Forward | 5′-ACA CCC TGT ACG AGT CGG TGT GC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGT TCT TCT GGA GGC CGC TGT AG-3′ | |

| CCR8 | Forward | 5′-TTC CTG CCT CGA TGG ATT AC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCT GGT CCA GCA GGT TGT GGG TCT-3′ | |

| CCR9 | Forward | 5′-ATG ATG CCC ACA GAA CTC ACA AGC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGC CTC CAG ACC TGA GCC TTC ATG-3′ | |

| CCR10 | Forward | 5′-TGC CAG AGC TCT GTT ACA AGG C-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTT TCA CAG TCT GCG TGA GGC T-3′ | |

| CXCR1 | Forward | 5′-GGC CGA GGC TGA ATA TTT CAT TCT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGT GGC ATG GAC GAT GGC CAG TAT-3′ | |

| CXCR2 | Forward | 5′-GGA GAA TTC AAG GTG GAT AAG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGT GTC TCT TCT GGA TCA GTG-3′ | |

| CXCR3 | Forward | 5′-GAG GTT AGT GAA CGT CAA GTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGG GTC CCT GCG GTA GAT CTG-3′ | |

| CXCR4 | Forward | 5′-GGT CTG GAG ACT ATG ACT CC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CAC AGA TGT ACC TGT CAT CC-3′ | |

| CXCR5 | Forward | 5′-TGG ATG ACC TGT ACA AGG AAC TGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AAC GGG AGG TGA ACC AGG CTC TAG-3′ | |

| CXCR6 | Forward | 5′-TAC GAG GGA GAT TTC TGG CTC TTC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ATA GTG GAT ATC TCC TCA CTG TGG-3′ | |

| CX3CR1 | Forward | 5′-ATG CCA TGT GCA AGC TCA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTT CAT GTC ACA ACT GGG-3′ |

Immunocytochemistry

Oligodendrocytes were identified using the CNPase antibody (Chemicon). Cells were pre-incubated in 1× PBS with 3% serum and 0.1% triton for one hour at room temperature. Cells were then incubated in 1× PBS with 1% goat serum, 0.1% triton, and anti-CNPase antibody (1:200 dilution) overnight at 4 degrees. After washing in 1× PBS, cells were incubated in 1× PBS with 1% goat serum and goat anti-mouse secondary antibody with conjugated alexafluor 633 at a ratio of 1:500 for 90 minutes at room temperature. Finally, cells were washed again with 1× PBS, mounted with Vecta Shield hard mounting media with DAPI and observed using a confocal microscope (Olympus).

Downregulation of CXCR4 using shRNA

To knockdown CXCR4 in oligospheres, we used short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-based RNA interference (RNAi) (Brummelkamp et al., 2002). Oligospheres were infected with an adenovirus, which expresses shRNA targeting CXCR4 and a fluorescence reporter protein (DsRed2) simultaneously. The plasmid vector that expresses shRNA and DsRed2 (pR-SHIN) was kindly provided by Drs. Shin-ichiro Kojima and Gary G. Borisy (Northwestern University, IL) (Kojima et al., 2004). The HindIII-NotI fragment containing shRNA and DsRed2 expression units of pR-SHIN was cloned into the pShuttle vector (pAd-SHIN-R) (He et al., 2002). The shRNA insert (the target sequence – loop – the reverse complement of the target sequence) was cloned into BglII/HindIII site of pAd-SHIN-R. Adenovirus was made using AdEasy System (Luo et al., 2007). The virus without a shRNA insert served as a control virus. We adopted the target sequence for CXCR4 RNAi published elsewhere (Smith et al., 2004): 5′-CCGATCAGTGTGAGTATAT-3′. Hairpin loop sequence was 5′-TTCAAGA-3′.

Quantitative PCR

Oligospheres from Olig2-EGFP mice were prepared as mentioned above. One week after the culture, oligospheres were infected with the aforementioned adenovirus, which expresses shRNA targeting CXCR4 and the red fluorescent protein (DsRed2) simultaneously. Three days later, the spheres were collected, digested with papain (Worthington, NJ) at 37 degrees for 20 min to produce single cells. DsRed2 positive and negative (non-infected) cells were collected using FACS sorting (Dako Cytomation MoFlo, Carpinteria, CA). Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed on a sequence detector (model SDS7500; Applied Biosystems) using primers for chemokine receptors (Tran et al., 2004) and SYBR PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer's instructions. For each cDNA sample, the relative level of the target gene and 18S expression was interpolated from the gene-specific standard curves. The expression of each target gene was normalized to the level of 18S expression.

Induction and clinical evaluation of peptide-induced EAE

6-7 week old female SJL/J mice were immunized s.c. with 100 μl of an emulsion containing 200 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco) and 50 μg proteolipid protein (residues 139-151) (PLP139-151) distributed over three spots on the flank. Clinical signs of EAE appeared typically after 12-14 days. The animals were observed daily and clinical scores assessed in a blinded fashion on a 0-5 scale as follows: 0, asymptomatic; 1, loss of tail tonicity; 2, atonic tail and hind leg weakness; 3, hind limb paralysis; 4, hind limb paralysis and forelimb weakness; 5, moribund.

Stereotaxic injections

Mice were anesthetized by an i.p. injection of sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg of body weight). Depth of anesthesia was confirmed by regular and relaxed respiratory rate and absence of withdrawal reflex upon foot pinch. Animals were then placed in a stereotaxic device. The skull was exposed and the needle of a 26 gauge 2 μl Hamilton syringe containing the cell preparation (approximately 2.106 cells/2 μl) was placed into the lateral ventricle with coordinates chosen according to the stereotaxic atlas of Paxinos (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001): anteriority:-0.2 mm, laterality: 1 mm from bregma, depth: -2.2 mm from the skull surface. The cells were injected at a constant flow rate of 0.2 μl/min over 10 minutes.

Tissue preparation

Three days, 6 days and 14 days after injections, EAE and control mice were anesthetized and perfused transcardially with cold PBS, followed by a freshly prepared solution of 4% PFA in PBS, pH 7.4. The brains were rapidly removed and post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C. Forty-micrometer thick coronal sections were cut with a vibratome (Leica VT 1000S; Leica Microsystems) and collected in cold PBS. Sections were then processed for histology or immunohistochemistry.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

To assess the expression of SDF-1 in EAE mice, sections of SDF-1-RFP/CXCR4-EGFP mice induced with EAE were analyzed by a confocal microscope and compared to naïve mice.

In order to analyze the migration and differentiation of oligospheres issued from wildtype (Olig2-EGFP) and CXCR4 knockout mice, serial coronal sections were mounted on slides and analyzed by a confocal microscope. The migration was compared to the injection site.

Other sections were processed for immunohistochemistry in order to identify the phenotype of differentiated cells. Immunohistochemistry was performed on free-floating sections using the following primary antibodies: anti-CNPase (1:200, Chemicon) to detect mature oligodendrocytes, anti- PLP antibody (1:500) to detect myelin, anti-GFAP (1:2000, Sigma) to characterize astrocytes, anti-IBA1 (1:1000, Wako) to label microglia and Olig1 (1:500, Chemicon) oligodendrocyte lineage marker. The appropriate isotype-specific secondary antibodies consisted of AlexaFluor 633 or 647-conjugated preparations (1:300; Molecular Probes).

Sections were incubated in PBS/4% goat serum/0.1% triton for 90 min. They were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in PBS/2% normal serum/0.1% triton overnight at 4°C. The sections were then washed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) for 1 hr. Sections were washed with PBS, mounted on slides, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Image acquisition software (Fluoview) was used.

Measurement of cell migration and differentiation

OPs migration distance was measured for EAE and naïve mouse brains. Images were taken at 10× magnification using a confocal microscope using the Fluoview software. The images were then overlapped using Adobe Photoshop to create a whole image of the injection site and medial and lateral migration. Migration distance in arbitrary units was calculated using the Metamorph program. Measurements were taken from the intersection of the injection path and the stem cell migratory stream to the most medially and most laterally migrated cell body. The data were reported as the mean±SEM of the total (medial + lateral) migration per experimental group. We quantified the differentiated cells by counting EGFP and/or DsRed2 positive cells within the corpus callosum and presented the data as mean±SEM per square millimeter of the white matter.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Multiple comparisons were statistically evaluated by t-test using SigmaStat 3.1 software. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Expression of chemokine receptors by oligodendrocyte progenitors

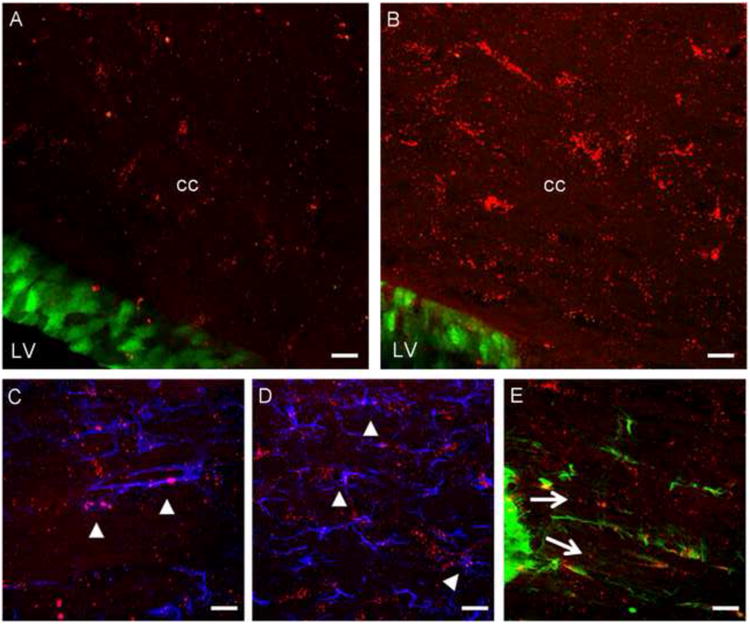

CXCR4 receptors are normally highly expressed by neural progenitors in the mouse SVZ (Tran et al., 2007). We also observed that SDF-1 was normally expressed in the corpus callosum (CC) (Fig.1A). We used SDF-1RFP/CXCR4-EGFP bitransgenic mice (Bhattacharyya et al., 2008) to examine the expression pattern of the chemokine and its receptor. These mice express a biologically active SDF1-mRFP fusion protein (Bhattacharyya et al., 2008; Jung et al., 2009). As we have previously demonstrated, the expression pattern of SDF-1 is punctate supporting the idea that it is normally stored in secretory vesicles (Bhattacharyya et al., 2008). Interestingly, we observed that the expression of SDF-1 in the CC was greatly upregulated in mice with EAE (Fig.1B), including expression by astrocytes and microglia as shown in Fig.1C and D. We also noted that CXCR4 is expressed by cells exhibiting the morphology of migrating progenitors in the posterior part of the SVZ (Fig. 1E). Immunostaining using an anti-Olig1 antibody showed that these CXCR4-expressing cells colocalize with Olig1 (Suppl. Fig. 1). Hence, we hypothesized that CXCR4 signaling might be important in regulating the migration of OPs from the SVZ into the white matter.

Figure 1. Expression of SDF-1-RFP and CXCR4-EGFP in SDF-1-RFP/CXCR4-EGFP bitransgenic mouse with EAE.

SDF-1-RFP/CXCR4-EGFP bitransgenic mice illustrate the presence of SDF-1-RFP (red) in the corpus callosum (cc) and CXCR4-EGFP (green) in the wall of the lateral ventricle (LV) in naïve (A) and EAE (B) mice brains. The expression of SDF-1 in the CC was greatly upregulated in mice with EAE (B) and was expressed by GFAP-labeled astrocytes (blue) and IBA-1- labeled microglia (blue) as shown in panels C and D respectively (arrowheads). CXCR4 is expressed by cells showing the morphology of migrating progenitors in the posterior part of the SVZ (E). Scale bars=50μm.

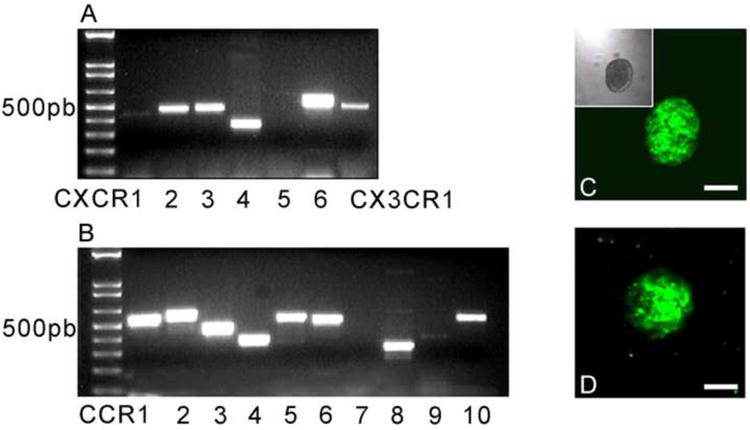

Neural progenitor cells can be grown in culture as neurospheres and differentiated in vitro to produce neurons or glia. It has also been reported that committed OPs can be grown in culture as “oligospheres” by switching the neurosphere cell culture medium to one containing PDGF (Pedraza et al., 2008; Vitry et al., 1999). Using this method, we grew oligospheres from Olig2-EGFP reporter mice that uniformly expressed EGFP (Fig. 2C). Olig2 is a gene whose expression is associated with the oligodendrocyte lineage (Lu et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2000). In order to examine the expression of chemokine receptors by OPs in vitro we performed RT-PCR on OPs from dissociated oligospheres. As shown in Fig. 2, numerous chemokine receptors of the CXCR and CCR families, as well as CX3CR1, were expressed by OPs.

Figure 2. Expression of chemokine receptors by oligodendrocyte progenitor cells.

Total RNA was extracted from oligospheres and RT-PCR was performed. Chemokine receptors of the CXC family (A), CCR family (B) and the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 (A) were expressed by OP cells. Panels C and D show oligosphere cultures from Olig-2-EGFP and CXCR4-EGFP transgenic mice respectively. Scale bars=50μm.

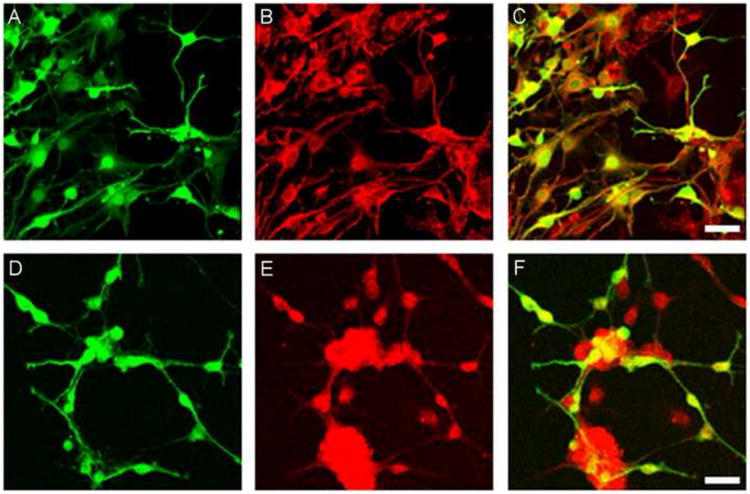

We also established oligosphere cultures from CXCR4-EGFP (Fig.2D) transgenic reporter mice. Oligospheres generated from CXCR4-EGFP mice also uniformly expressed EGFP, consistent with the RT-PCR results discussed above. The ability of oligospheres to generate differentiated oligodendrocytes was examined in vitro following plating of dissociated oligospheres obtained from Olig2-EGFP (Fig.3A-C) and CXCR4-EGFP (Fig.3D-F) transgenic mice. We used culture conditions designed to favor oligodendrocyte development. Under these circumstances oligosphere derived cells developed the morphology of oligodendrocytes and still expressed EGFP. Moreover, differentiated Olig2-EGFP and CXCR4-EGFP positive cells stained for CNPase (Fig.3), a marker for cells of the oligodendrocyte lineage.

Figure 3. Olig2-EGFP and CXCR4-EGFP oligospheres differentiate into oligodendrocytes in vitro.

The ability of oligospheres to generate differentiated oligodendrocytes was examined in vitro following plating them on coverslips. Oligospheres from Olig2-EGFP and CXCR4-EGFP transgenic mice generated the morphology of oligodendrocytes (panels A and D respectively). Immunohistochemistry was performed using an oligodendrocyte marker, CNPase (red labeling in panels B and E). Panels C and F show the co-localization of Olig2-EGFP (C) and CXCR4-EGFP (F) oligodendrocytes with CNPase. Scale bars=50μm.

Migration of transplanted OPs into the white matter

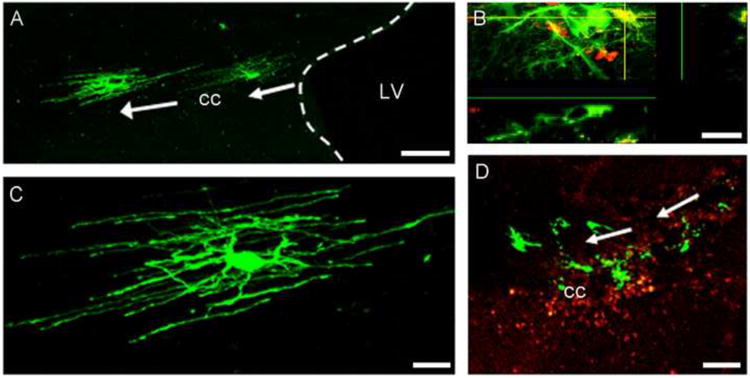

To investigate the migratory capacity of oligosphere derived OPs in vivo, we transplanted dissociated OPs into the lateral ventricles of naive SJL mice as well as mice exhibiting relapsing-remitting EAE induced by the injection of PLP peptide. OPs cultured from Olig2-EGFP mice were transplanted at the peak of disease (day 15 post-immunization (p.i.)). We observed that significant migration into the white matter occurred as early as 1 day after transplantation. The third day after injection, cells with differentiated morphologies were distributed along the medial-lateral axis, exclusively in the white matter. Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of Olig2-EGFP expressing cells in the CC of EAE mice 2 weeks after transplantation.

Figure 4. Transplanted Olig2-EGFP OPs integrate into the demyelinated white matter and differentiate into oligodendrocytes in vivo.

Dissociated OPs from Olig2-EGFP mice were injected into the lateral ventricle (LV) of EAE mice at the peak of the disease. Two weeks post-transplantation, Olig2-EGFP cells migrated into the media-lateral axis of the corpus callosum (cc) (A) and differentiated into cells with the morphology of oligodendrocytes (C). Panel B shows the co-localization of a differentiated Olig2-EGFP cell (green) with the oligodendrocyte marker, CNPase (red). Panel D shows that Olig2-EGFP cells (green) migrate to areas of demyelination as characterized using an anti-PLP antibody (red) that stains for the myelin surrounding the demyelinated area. Scale bars in A and D=100μm, scale bars in C and B =20μm.

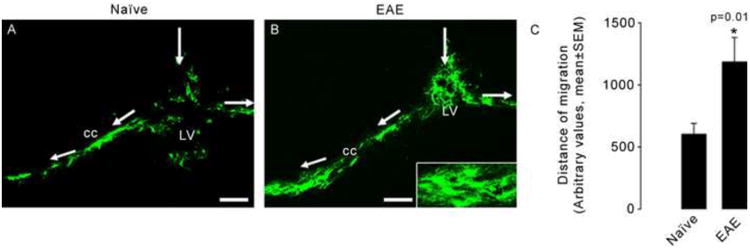

Detailed examination of these tissues by confocal microscopy showed that migrating cells derived from injected OPs had the morphology of oligodendrocytes (Fig.4A,C), consistent with the results of the cell culture studies. Cells with the morphology of both myelinating and non myelinating oligodendrocytes were observed (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemistry using the oligodendrocyte marker CNPase (Fig.4B) further confirmed that injected OPs had differentiated into oligodendrocytes and were confined within areas of demyelination in the white matter, as shown in sections stained for the myelin marker PLP (Fig.4D). Figure 5 illustrates the migration of Olig2-EGFP OPs in naïve and EAE mice, respectively. In both cases, cells integrated into the white matter and migrated into the CC. Quantitation of the distance cells had migrated indicated that they migrated further in EAE compared to naïve mice (Fig. 5C). More Olig2-EGFP differentiated cells were also observed in EAE tissue (120.1±9 cells/mm2, n=10) when compared to naïve mouse brain (79.8±8 cells/mm2, n=6; t test, p=0.01).

Figure 5. Olig2-EGFP OPs migrate further in EAE than in control mice.

Olig2-EGFP OPs were injected into the lateral ventricle (LV) of naïve (A) and EAE (B) mice. Cells migrated into the corpus callosum (cc) and differentiated into oligodendrocytes (insert in B). Quantification of the migration distance showed that cells migrate further in EAE animals. As seen in panel B, more cells are observed in EAE tissue. The histogram in C shows the average distance of migration for oligospheres in naïve (n=6) and EAE (n=10) mice (t test, P=0.01). Scale bars=100μm.

Chemokine signaling in OP migration

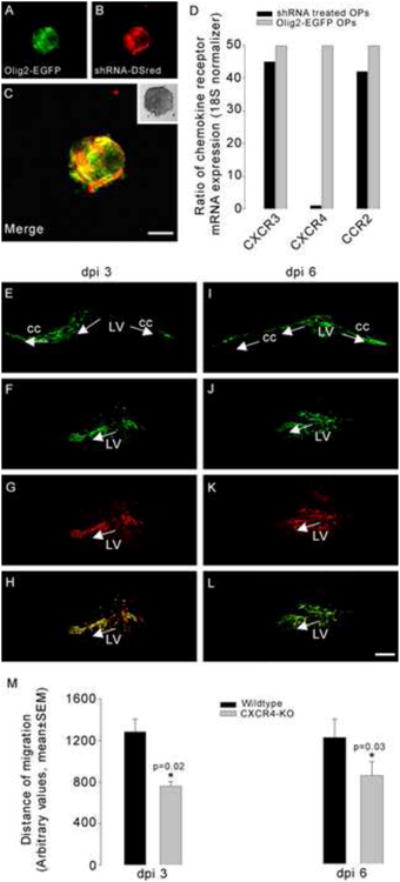

In the next series of experiments we attempted to ascertain whether interference with CXCR4 signaling would impact the ability of OPs to migrate into the CC of EAE mice. To inhibit the expression of CXCR4 receptors specifically in OPs, Olig2-EGFP oligospheres were infected with an adenovirus that expressed DsRed2 as well as shRNA targeting CXCR4 receptors (Fig.6). Following infection, OPs were separated by FACS into EGFP (green) and EGFP/DsRed2 (yellow) populations. Cells that expressed both Olig2-EGFP and shRNA-DsRed2 appeared yellow and lacked CXCR4 expression (Fig. 6). Green cells that lacked shRNA maintained CXCR4 expression. Olig2-EGFP cells infected with a virus expressing only DsRed2 without shRNA were also used as a control for any effects of the shRNA virus. The expression levels of CXCR4 in these cells were the same as uninfected cells. Quantitative PCR showed that the expression of CXCR4 was greatly reduced in shRNA expressing cells while the expression of other chemokine receptors including CXCR3 and CCR2 was not altered, indicating the specificity of the shRNA virus (Fig.6D). The histogram in Fig.6D shows the level of CXCR4 after 3 days of infection with shRNA. Similar in vitro levels of CXCR4 were obtained after 14 days of culture (not shown).

Figure 6. Impaired migration of OPs in EAE mice following downregulation of CXCR4 expression.

Olig2-EGFP oligospheres were infected with an adenovirus, which expresses shRNA targeting CXCR4 and a fluorescent reporter protein (DsRed2) (A-C). Histogram in D illustrates the ratio of chemokine receptor mRNA expression in shRNA treated OPs to non-infected Olig2-EGFP OPs. Quantitative PCR showed that the expression of CXCR4 was significantly downregulated in shRNA expressing cells while the expression of other chemokine receptors e.g. CXCR3 and CCR2 was not downregulated. Three days post injection (dpi), both untreated Olig2-EGFP (E) and shRNA treated cells (F-H) migrated into the corpus callosum (cc) and differentiated into oligodendrocytes. Green labeling shows the Olig-2-EGFP expression and the red fluorescence corresponds to DsRed. The merged cells expressing both green and red fluorescence (H) are cells infected with the shRNA (CXCR4 KO). At 6 days post injection, cells obtained from untreated Olig2-EGFP (I) and shRNA treated Olig2-EGFP OPs (J-L) were still observed in the corpus callosum of EAE mice. Migration distance in arbitrary units was calculated using the Metamorph program. Measurements were taken from the intersection of the injection path and the stem cell migratory stream to the most medially and most laterally migrated cell body. The data were reported as the mean±SEM of the total (medial + lateral) migration per experimental group. We quantified the differentiated cells by counting EGFP and/or DsRed2 positive cells within the corpus callosum and presented the data as mean±SEM per square millimeter of the white matter. Quantification of the lateral and medial migration of OPs showed that CXCR4 KO cells migrated less than untreated (wildtype) Olig2-EGFP cells (histogram in M) or cells treated with an adenovirus expressing DsRed2 but no shRNA (not shown in the histogram). Similar results were obtained at 3 and 6 days post injection. Asterisks mark statistically significant results (t test, p=0.02 and 0.03). Scale bars=100μm.

We next compared the migration of uninfected cells (EGFP/green) with virus infected cells (EGFP+DsRed2/yellow). OPs were transplanted at the peak of EAE disease. Three days following transplantation both EGFP/green (Fig.6E) and EGFP+DsRed2/yellow (Figs.6F-H) cells had migrated and were integrated into the CC. Detailed examination of brain sections demonstrated that OPs infected with the control DsRed2 virus that did not express shRNA migrated extensively into the CC in a similar manner to uninfected Olig2-EGFP OPs, while cells infected with the shRNA DsRed2 expressing virus were localized closer to the lateral ventricle. Six days after injection of the OPs similar results were obtained (Figs.6I-L). Quantification of migration distances confirmed that cells infected with the shRNA expressing virus migrated a significantly shorter distance in comparison to OPs infected with the control virus or to uninfected Olig2-EGFP OPs (Fig.6M). Moreover, the density of differentiated OPs within the white matter was significantly increased when comparing OPs infected with the control virus (100.3±5 cells/mm2, n=10) or non-transfected Olig-2-EGFP cells (98.1±8 cells/mm2, n=8) to shRNA infected cells (50.4±3 cells/mm2, n=8) (t test, p=0.0047). These data suggest that SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling is involved in the migration of transplanted OPs into the white matter.

Discussion

Cell replacement therapy is an important potential treatment for a variety of CNS disorders including neurodegenerative and demyelinating diseases. Both embryonic and adult neural stem cells have been proposed as a source of brain cells for transplantation purposes (Temple, 2001). In order for such therapy to be successful progenitors must first migrate appropriately and must then integrate functionally. We have now shown that OPs transplanted into the lateral ventricles will migrate into the white matter and that this is due, at least in part, to the influence of the chemokine SDF-1 signaling via its receptor CXCR4. In adult rodents OPs can develop from GFAP expressing stem cells in the SVZ, particularly in response to demyelination (Menn et al., 2006). Thus, lysophosphatidylcholine induced demyelination of the CC or the induction of EAE enhances the proliferation of OPs in the SVZ and their migration to sites of demyelination where they can become mature myelinating oligodendrocytes (Menn et al., 2006; Nait-Oumesmar et al., 2007). Similarly, neural progenitors transplanted into the lateral ventricles have also been shown to migrate into the white matter to form mature myelinating cells (Carbajal et al., 2010; Cayre et al., 2006; Nait-Oumesmar et al., 2008), presumably because these transplanted cells integrate themselves into the same migratory routes as those utilized by endogenous progenitors (Menn et al., 2006; Parent et al., 2006). For example, human neural progenitors transplanted into the ventricles of shiverer mice, which lack myelin expression, will migrate effectively and remyelinate the CC (Windrem et al., 2004).

Several previous studies have also shown that endogenous or transplanted neural progenitors will migrate towards areas of brain damage although the mechanisms underlying this directed migration have not been generally clear (Aboody et al., 2000; Ben-Hur et al., 2003; Glass et al., 2005; Pluchino and Martino, 2005; Pluchino et al., 2003; Pluchino et al., 2005). Nevertheless, a role for chemokines in this migratory response has been previously suggested (Belmadani et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2007). In particular, signaling via the CXCR4 receptor has been shown to be important for the migration of progenitors in the brain in response to different types of pathology. Following stroke, for example, CXCR4 is expressed by neural progenitors that migrate to areas of brain damage (Ceradini et al., 2004; Ohab et al., 2006). The source of these cells appears to be the SVZ where large numbers of CXCR4 expressing progenitors normally reside (Tran et al., 2007). SDF-1 is expressed by endothelial cells and astrocytes in the stroke penumbra and interference with CXCR4 signaling inhibits the migration of progenitors to stroke induced areas of damage (Ohab et al., 2006). Other reports have indicated that signaling via the CCR2 chemokine receptor may also be important under similar circumstances. Indeed MCP-1/CCL2, the ligand for this receptor is up-regulated by microglia and astrocytes in response to stroke induced damage and CCR2 receptors are also expressed by migrating neural progenitors (Belmadani et al., 2006; Tran et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2007). A role for chemokine signaling in directing the migration of adult OPs might also be anticipated based on the known regulation of OP migration by chemokines during development of the spinal cord. It has been demonstrated that OPs in the developing spinal cord express CXCR4 and CXCR2 receptors and that the chemokine ligands for these receptors such as SDF-1 and CXCL1 play a role in the migration and proliferation of these cells during development (Dziembowska et al., 2005; Tsai et al., 2002). In a very recent study, using an experimental murine model of demyelination mediated by the copper chelator cuprizone, Patel et al. (2010) suggest that upregulation of SDF-1 is essential for the migration and differentiation of CXCR4-expressing OPCs into mature oligodendrocytes within the demyelinated CC in vivo. Consistent with our findings, it has also recently been shown that in a viral model of MS, SDF-1 signaling through CXCR4 plays a key role in regulating the homing of engrafted neuronal stem cells to the white matter (Carbajal et al., 2010).

In the adult brain SDF-1 is constitutively expressed by endothelial cells in blood vessels as well as by different types of cells including astrocytes and neurons (Banisadr et al., 2003; Bhattacharyya et al., 2008; McCandless et al., 2006; Moll et al., 2009). It has been shown that SDF-1 plays a role in the attraction of lymphocytes (Bleul et al., 1996; Crump et al., 1998) and, in particular, CXCR4 signaling has been suggested as playing a particular role in the positioning of lymphocytes in the CNS at the blood brain barrier (BBB). For example, McCandless et al. (2006) showed that during EAE, blockade of CXCR4 using the antagonist AMD3100 induced more severe disease with increased infiltration of immune cells into the parenchyma. In the normal CNS, SDF-1 was expressed at the basolateral side of the endothelium, attracting CXCR4 expressing leukocytes to this region and restricting their migration into the tissue. This pattern of expression changed during the peak of the subsequent disease resulting in a loss of SDF-1 polarity, suggesting that disruption of this chemokine gradient could play a role in the extravasation of leukocytes into the CNS parenchyma. Recently, the same group confirmed this hypothesis in humans with immunohistochemical analysis of SDF-1 expression at the BBB in CNS tissues from MS and non-MS patients (McCandless et al., 2008). They showed that MS was also associated with an altered SDF-1 expression toward the luminal side of blood vessels, which may contribute to the release of leukocytes from their perivascular localization, promoting leukocyte entry into the brain parenchyma. Thus, the SDF-1 is probably crucial for retaining inflammatory CXCR4-positive cells in the perivascular space, preventing them from migrating into the parenchyma and causing injury.

We have found that downregulation of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in OPs resulted in an impaired migration of these cells into the CC suggesting a critical role for SDF-1/CXCR4 in the directed migration of OPs. We observed that SDF-1 was normally expressed in the CC and its expression was enhanced in animals with EAE. This is consistent with the observation that SDF-1 expression is enhanced in astrocytes in the brains of patients with MS (Moll et al., 2009). Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that expression of SDF-1 in the areas of demyelination is one important factor that regulates directed OP migration under these circumstances. As the inhibition of CXCR4 expression only partially inhibited migration it is clear that other factors, possibly including other chemokines, are also involved in the observed migration. Indeed, numerous chemokines are expressed in the brain as part of the inflammatory response associated with MS/EAE and as we have now demonstrated numerous chemokine receptors are expressed by OPs.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that chemokine signaling is important in the survival of transplanted OPs and their migration into the white matter of EAE mice, a major step in promoting repair within an inflammatory milieu relevant to MS. Also, these results further highlight that transplantation of OPs may be useful as a therapeutic tool in chronic inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the adult brain and promote myelin repair. Clearly enhancement of CXCR4 signaling by OPs might result in more efficient myelination in MS. This might be achieved by enhancing the expression of SDF-1 in the appropriate place. Another possibility, however, might be to modulate pathways that normally inhibit CXCR4 signaling. For example, recent publications illustrating the modulatory role of the CXCR7 receptor on CXCR4 signaling during neural progenitor development might suggest that CXCR7 inhibitors could result in enhanced CXCR4 signaling (Sánchez-Alcañiz et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). Indeed, the observation that CXCR7 is normally strongly expressed in the adult SVZ suggests that it may also play an important role in the regulation of adult OP development. On the other hand, Göttle et al. (2010) have shown that activation of the CXCR7 receptor can promote oligodendroglial cell maturation in diseased brain. Moreover, the up-regulation of SDF-1 within the demyelinated white matter as demonstrated in our experiments, might also serve to promote the differentiation of CXCR4-expressing OPCs into myelin-producing oligodendrocytes, as recently reported in the literature (Patel et al., 2010). Further investigations targeting this endogenous pathway may give us insights on the regulation of demyelination/remyelination episodes during MS.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figure 1: Expression of CXCR4-EGFP in Olig1-expressing cells in the subventricular zone of SDF-1-RFP/CXCR4-EGFP bitransgenic mouse with EAE. In order to characterize CXCR4-expressing cells in the SVZ, immunostaining was performed using an anti-Olig1 antibody. CXCR4-EGFP expressing cells (A) colocalized with Olig1 immunoreactive cells (B). C: Overlap from immunoreactivity of Alexa 647-labeled Olig1 (red) and CXCR4-EGFP expressing cells (green). Scale bars=25μm.

Research highlights.

Oligodendrocyte progenitors (OPs) expressed chemokine receptors.

OPs migrated into the corpus callosum in EAE mice.

OPs differentiated into mature oligodendrocytes in vivo.

Downregulation of CXCR4 using shRNA inhibited the migration of transplanted OPs.

Directed migration of OPs is regulated by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mary Beth Hatten (Rockefeller University) for the gift of transgenic mice. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Dana Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aboody KS, Brown A, Rainov NG, Bower KA, Liu S, Yang W, Small JE, Herrlinger U, Ourednik V, Black PM, Breakefield XO, Snyder EY. Neural stem cells display extensive tropism for pathology in adult brain: evidence from intracranial gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12846–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagri A, Gurney T, He X, Zou YR, Littman DR, Tessier-Lavigne M, Pleasure SJ. The chemokine SDF1 regulates migration of dentate granule cells. Development. 2002;129:4249–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.18.4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banisadr G, Skrzydelski D, Kitabgi P, Rostene W, Parsadaniantz SM. Highly regionalized distribution of stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCL12 in adult rat brain: constitutive expression in cholinergic, dopaminergic and vasopressinergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1593–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmadani A, Tran PB, Ren D, Assimacopoulos S, Grove EA, Miller RJ. The chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 regulates the migration of sensory neuron progenitors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3995–4003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4631-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmadani A, Tran PB, Ren D, Miller RJ. Chemokines regulate the migration of neural progenitors to sites of neuroinflammation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3182–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0156-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur T, Einstein O, Mizrachi-Kol R, Ben-Menachem O, Reinhartz E, Karussis D, Abramsky O. Transplanted multipotential neural precursor cells migrate into the inflamed white matter in response to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Glia. 2003;41:73–80. doi: 10.1002/glia.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya BJ, Banisadr G, Jung H, Ren D, Cronshaw DG, Zou Y, Miller RJ. The chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 regulates GABAergic inputs to neural progenitors in the postnatal dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6720–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1677-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleul CC, Farzan M, Choe H, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer TA. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature. 1996;382:829–33. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbajal KS, Schaumburg C, Strieter R, Kane J, Lane TE. Migration of engrafted neural stem cells is mediated by CXCL12 signaling through CXCR4 in a viral model of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11068–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006375107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayre M, Bancila M, Virard I, Borges A, Durbec P. Migrating and myelinating potential of subventricular zone neural progenitor cells in white matter tracts of the adult rodent brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:748–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayre M, Canoll P, Goldman JE. Cell migration in the normal and pathological postnatal mammalian brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;88:41–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, Tepper OM, Bastidas N, Kleinman ME, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10:858–64. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump MP, Rajarathnam K, Kim KS, Clark-Lewis I, Sykes BD. Solution structure of eotaxin, a chemokine that selectively recruits eosinophils in allergic inflammation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22471–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziembowska M, Tham TN, Lau P, Vitry S, Lazarini F, Dubois-Dalcq M. A role for CXCR4 signaling in survival and migration of neural and oligodendrocyte precursors. Glia. 2005;50:258–69. doi: 10.1002/glia.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass R, Synowitz M, Kronenberg G, Walzlein JH, Markovic DS, Wang LP, Gast D, Kiwit J, Kempermann G, Kettenmann H. Glioblastoma-induced attraction of endogenous neural precursor cells is associated with improved survival. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2637–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5118-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göttle P, Kremer D, Jander S, Odemis V, Engele J, Hartung HP, Küry P. Activation of CXCR7 receptor promotes oligodendroglial cell maturation. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:915–24. doi: 10.1002/ana.22214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Bell AF, Tonge PJ. Synthesis and spectroscopic studies of model red fluorescent protein chromophores. Org Lett. 2002;4:1523–6. doi: 10.1021/ol0200403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Bhangoo S, Banisadr G, Freitag C, Ren D, White FA, Miller RJ. Visualization of chemokine receptor activation in transgenic mice reveals peripheral activation of CCR2 receptors in states of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8051–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0485-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RS, Rubin JB. Immune and nervous system CXCL12 and CXCR4: parallel roles in patterning and plasticity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:306–14. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RS, Rubin JB, Gibson HD, DeHaan EN, Alvarez-Hernandez X, Segal RA, Luster AD. SDF-1 alpha induces chemotaxis and enhances Sonic hedgehog-induced proliferation of cerebellar granule cells. Development. 2001;128:1971–81. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S, Vignjevic D, Borisy GG. Improved silencing vector co-expressing GFP and small hairpin RNA. Biotechniques. 2004;36:74–9. doi: 10.2144/04361ST02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Ransohoff RM. Multiple roles of chemokine CXCL12 in the central nervous system: a migration from immunology to neurobiology. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:116–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XS, Zhang ZG, Zhang RL, Gregg SR, Wang L, Yier T, Chopp M. Chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) induces migration and differentiation of subventricular zone cells after stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2120–5. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QR, Sun T, Zhu Z, Ma N, Garcia M, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Common developmental requirement for Olig function indicates a motor neuron/oligodendrocyte connection. Cell. 2002;109:75–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QR, Yuk D, Alberta JA, Zhu Z, Pawlitzky I, Chan J, McMahon AP, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Sonic hedgehog--regulated oligodendrocyte lineage genes encoding bHLH proteins in the mammalian central nervous system. Neuron. 2000;25:317–29. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Deng ZL, Luo X, Tang N, Song WX, Chen J, Sharff KA, Luu HH, Haydon RC, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, He TC. A protocol for rapid generation of recombinant adenoviruses using the AdEasy system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1236–47. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCandless EE, Piccio L, Woerner BM, Schmidt RE, Rubin JB, Cross AH, Klein RS. Pathological expression of CXCL12 at the blood-brain barrier correlates with severity of multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:799–808. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCandless EE, Wang Q, Woerner BM, Harper JM, Klein RS. CXCL12 limits inflammation by localizing mononuclear infiltrates to the perivascular space during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:8053–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menn B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yaschine C, Gonzalez-Perez O, Rowitch D, Alvarez-Buylla A. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7907–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll NM, Cossoy MB, Fisher E, Staugaitis SM, Tucky BH, Rietsch AM, Chang A, Fox RJ, Trapp BD, Ransohoff RM. Imaging correlates of leukocyte accumulation and CXCR4/CXCL12 in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:44–53. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nait-Oumesmar B, Picard-Riera N, Kerninon C, Baron-Van Evercooren A. The role of SVZ-derived neural precursors in demyelinating diseases: from animal models to multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2008;265:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nait-Oumesmar B, Picard-Riera N, Kerninon C, Decker L, Seilhean D, Hoglinger GU, Hirsch EC, Reynolds R, Baron-Van Evercooren A. Activation of the subventricular zone in multiple sclerosis: evidence for early glial progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4694–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606835104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohab JJ, Fleming S, Blesch A, Carmichael ST. A neurovascular niche for neurogenesis after stroke. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13007–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4323-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent JM, von dem Bussche N, Lowenstein DH. Prolonged seizures recruit caudal subventricular zone glial progenitors into the injured hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2006;16:321–8. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JR, McCandless EE, Dorsey D, Klein RS. CXCR4 promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitors and remyelination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11062–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006301107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Second. Elsevier; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza CE, Monk R, Lei J, Hao Q, Macklin WB. Production, characterization, and efficient transfection of highly pure oligodendrocyte precursor cultures from mouse embryonic neural progenitors. Glia. 2008;56:1339–52. doi: 10.1002/glia.20702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluchino S, Martino G. The therapeutic use of stem cells for myelin repair in autoimmune demyelinating disorders. J Neurol Sci. 2005;233:117–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluchino S, Quattrini A, Brambilla E, Gritti A, Salani G, Dina G, Galli R, Del Carro U, Amadio S, Bergami A, Furlan R, Comi G, Vescovi AL, Martino G. Injection of adult neurospheres induces recovery in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2003;422:688–94. doi: 10.1038/nature01552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluchino S, Zanotti L, Rossi B, Brambilla E, Ottoboni L, Salani G, Martinello M, Cattalini A, Bergami A, Furlan R, Comi G, Constantin G, Martino G. Neurosphere-derived multipotent precursors promote neuroprotection by an immunomodulatory mechanism. Nature. 2005;436:266–71. doi: 10.1038/nature03889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Alcañiz JA, Haege S, Mueller W, Pla R, Mackay F, Schulz S, López-Bendito G, Stumm R, Marín O. Cxcr7 controls neuronal migration by regulating chemokine responsiveness. Neuron. 2011;69:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MC, Luker KE, Garbow JR, Prior JL, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, Luker GD. CXCR4 regulates growth of both primary and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8604–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple S. The development of neural stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:112–7. doi: 10.1038/35102174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thored P, Arvidsson A, Cacci E, Ahlenius H, Kallur T, Darsalia V, Ekdahl CT, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Persistent production of neurons from adult brain stem cells during recovery after stroke. Stem Cells. 2006;24:739–47. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PB, Banisadr G, Ren D, Chenn A, Miller RJ. Chemokine receptor expression by neural progenitor cells in neurogenic regions of mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:1007–33. doi: 10.1002/cne.21229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PB, Miller RJ. Chemokine receptors: signposts to brain development and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:444–55. doi: 10.1038/nrn1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PB, Ren D, Veldhouse TJ, Miller RJ. Chemokine receptors are expressed widely by embryonic and adult neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:20–34. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HH, Frost E, To V, Robinson S, Ffrench-Constant C, Geertman R, Ransohoff RM, Miller RH. The chemokine receptor CXCR2 controls positioning of oligodendrocyte precursors in developing spinal cord by arresting their migration. Cell. 2002;110:373–83. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitry S, Avellana-Adalid V, Hardy R, Lachapelle F, Baron-Van Evercooren A. Mouse oligospheres: from pre-progenitors to functional oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:735–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li G, Stanco A, Long JE, Crawford D, Potter GB, Pleasure SJ, Behrens T, Rubenstein JL. CXCR4 and CXCR7 have distinct functions in regulating interneuron migration. Neuron. 2011;69:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windrem MS, Nunes MC, Rashbaum WK, Schwartz TH, Goodman RA, McKhann G, 2nd, Roy NS, Goldman SA. Fetal and adult human oligodendrocyte progenitor cell isolates myelinate the congenitally dysmyelinated brain. Nat Med. 2004;10:93–7. doi: 10.1038/nm974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YP, Sailor KA, Lang BT, Park SW, Vemuganti R, Dempsey RJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 plays a critical role in neuroblast migration after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1213–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figure 1: Expression of CXCR4-EGFP in Olig1-expressing cells in the subventricular zone of SDF-1-RFP/CXCR4-EGFP bitransgenic mouse with EAE. In order to characterize CXCR4-expressing cells in the SVZ, immunostaining was performed using an anti-Olig1 antibody. CXCR4-EGFP expressing cells (A) colocalized with Olig1 immunoreactive cells (B). C: Overlap from immunoreactivity of Alexa 647-labeled Olig1 (red) and CXCR4-EGFP expressing cells (green). Scale bars=25μm.