ABSTRACT

Stillbirth and neonatal mortality are significant problems in captive breeding of dolphins, however, the causes of these problems are not fully understood. Here, we report a case of meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) in a male neonate of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncates) who died immediately after birth. At necropsy, a true knot was found in the umbilical cord. The lungs showed diffuse intraalveolar edema, hyperemic congestion and atelectasis due to meconium aspiration with mild inflammatory cell infiltration. Although the exact cause of MAS in this case was unknown, fetal hypoxia due possibly to the umbilical knot might have been associated with MAS, which is the first report in dolphins. MAS due to perinatal asphyxia should be taken into account as a possible cause of neonatal mortality and stillbirth of dolphin calves.

Keywords: bottlenose dolphin, meconium aspiration, true knot, umbilical cord

Stillbirth and neonatal mortality of calves are important problems in captive cetaceans. Joseph et al. revealed 8% abortion and 8.8% stillbirth rates in bottlenose dolphins from 1995 through 2000 [14]. However, the causes of these problems are not fully understood, because of a small amount of information including pathology.

Meconium is a sticky dark green substance containing gastrointestinal secretions, bile, bile acids, mucus, pancreatic juice, intestinal juice, blood, swallowed vernix caseosa, lanugo and cellular debris [15, 18]. Meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) is defined as a serious respiratory disorder of the infant born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) that cannot be otherwise explained; MAS is caused by exclusively aspiration of meconium in the airways during intrauterine gasping or during the first few breaths [1, 13, 15, 18]. MAS has been reported in human infants, neonatal calves [10] and piglets [5], and the occurrence is very rare in other species [6]. In humans, MSAF is present in 8–20% of all deliveries, and 2–9% of infants born through MSAF develop MAS [15]. In dolphins, there has been one report of meconium aspiration; a case of Escherichia coli septicemia associated with meconium aspiration and lack of maternally acquired immunity [17]. Because of the rarity, here, we document a case of MAS in a bottlenose dolphin calf died immediately after birth.

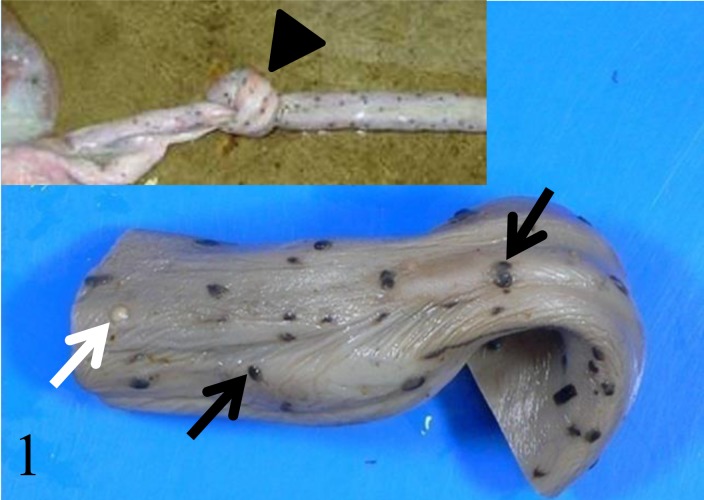

A male neonate of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncates) died immedietly after birth. There were no complications during labor. After birth, the calf transiently swam toward water surface for breathing, but failed to breath and died. At necropsy, a true knot was found in the umbilical cord (Fig. 1: inset, arrowhead), and there were many black or white plaques on its surface (Fig. 1: arrows). The cord length of the present case was not measured. Pulmonary atelectasis was also observed, and the intestines contained yellowish fluid. There were neither gross findings suggesting cyanosis nor significant lesions in other organs examined. The following tissues were sampled for histopathologic examination: liver, spleen, kidneys, heart, lungs, esophagus, stomach, intestines, lymph nodes, cerebrum and umbilical cord. Tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 3 µm thick were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Selected sections were also stained by periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Schmorl reaction and were applied to melanin bleaching. For immunohistochemistry, sections from lung and umbilical cord were stained with mouse anti-cytokeratin (clone AE1/AE3, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, 1:1,000) for 16 hr at 4°C. Bound antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Histofine Simplestain MAX-PO; Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) and 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.) as chromogen.

Fig. 1.

Dolphin calf who died immediately after the birth. A true knot is seen in the umbilical cord (inset; arrowhead) and many black or white plaques (black or white arrows, respectively) on its surface. These plaques (amniotic pearls or callosities) are regarded as normal umbilical cord structures in cetacean.

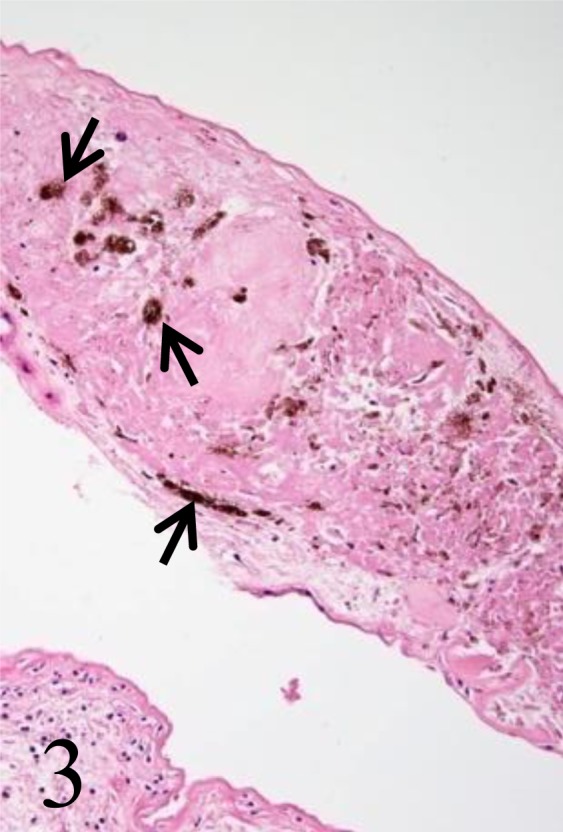

Histologically, the white plaques on the umbilical cord surface were foci of cytokeratin-positive epithelium with cornified outer layers (Fig. 2). The black plaques consisted of keratinizing squamous epithelium and keratin debris with melanin deposition (Fig. 3). These plaques composed of squamous metaplasia (amniotic pearls or callosities) are regarded as normal umbilical cord structures in cetacean and ungulates [3, 8, 11]. No histopathological abnormalities including necrosis or hemorrhage were observed in the umbilical cord.

Fig. 2.

Histologically, the white plaques on the umbilical surface are composed of keratinizing squamous epithelium (Fig. 2a) positive for cytokeratin (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 3.

The black plaques consist of keratinizing squamous epithelium and keratin debris with melanin deposition (arrows).

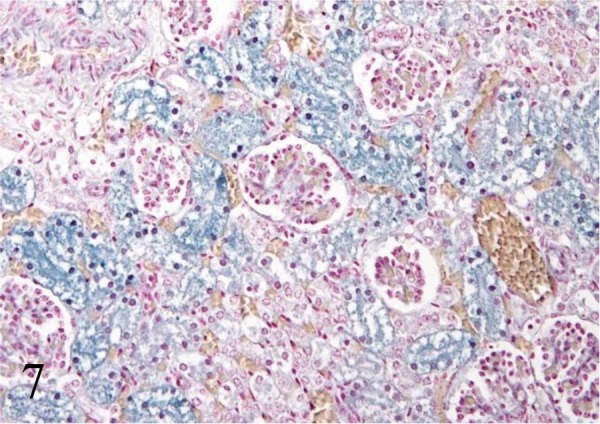

The lungs showed diffuse atelectasis consisting of loss of air spaces, intraalveolar edema, hyperemic congestion, mild infiltration of inflammatory cells including a few multinucleated giant cells and moderate meconium aspiration (Fig. 4a and 4b). Large aggregates of meconium occasionally totally filled the lumen of airways (Fig. 4b: inset and Fig. 5). In the lumina of alveoli and bronchi, moderate accumulation of eosinophilic amorphous materials containing brown pigments was observed (Fig. 5: asterisk). These amorphous materials were stained red with PAS reaction (Fig. 5: inset), and brown pigments were melanin granules which were confirmed by Schmorl reaction and melanin bleaching. Numerous eosinophilic long filamentous materials with occasional central nuclei and melanin granules were also present (Fig. 5: arrows). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that all filamentous structures and a part of amorphous materials were positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (Fig. 6), indicating that these components were squamous epithelial cells or keratin. There were no evidences of infection with infectious agents including pathogenic fungi and bacteria in the lungs. Histopathological finding seen in other organs included severe lipofuscin deposition in the renal tubular epithelium (Fig. 7) and congestion in the kidneys, liver and heart.

Fig. 4.

In the lungs, diffuse intraalveolar edema, hyperemic congestion (Fig. 4a), atelectasis and meconium aspiration (Fig. 4b) are observed. Large aggregates of meconium occasionally totally fill the lumen of airways (Fig. 4b; arrow and inset).

Fig. 5.

The lumen of alveoli contains eosinophilic amorphous materials with brown pigments (asterisk). Numerous eosinophilic long filamentous materials with occasional central nuclei are also present (arrows). The amorphous materials containing melanin pigments in the alveoli are stained red with PAS reaction (inset).

Fig. 6.

The filamentous structures are strongly positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 with occasional central nuclei (inset; arrowheads).

Fig. 7.

In the kidneys, severe lipofuscin deposition in the renal tubular epithelium is observed. Schmorl reaction.

The histopathologic findings of the lungs including meconium aspiration, atelectasis and intraalveolar edema with mild inflammation were consistent with those of MAS in domestic animals [1, 6, 10, 17]. This dolphin may have died from pulmonary dysfunction caused presumably by the aspiration of meconium including keratinizing squamous epithelium and keratin debris. Therefore, the present case was diagnosed as MAS. MAS results from aspiration of meconium during intrauterine gasping or during the first few breaths. Fetal hypoxic stress and acidosis can lead to a vagal response with increased peristalsis and a relaxed anal sphineter, resulting in the passage of meconium into the amniotic fluid. In addition, fetal gasping movements during the later phase of asphyxia result in aspiration of the meconium [1, 13, 15]. The pathophysiology of MAS is remarkably complex, and several factors are involved including: (1) airway obstructions and atelectasis: (2) chemical pneumonitis with release of vasoconstrictive and inflammatory mediators: (3) inactivation of pulmonary surfactant [1, 13, 15]. In addition, MAS can lead to pulmonary edema associated with increased pulmonary vascular permeability by activation of pulmonary macrophages or by vascular leakage caused through the release of inflammatory mediators [1, 15]. In the present case, atelectasis was considered to be due to both fetal atelectasis and meconium aspiration; intraalveolar edema may have been attributable to meconium aspiration to some degree, besides possible aspiration of sea water and amniotic fluid.

One of the causes of fetal asphyxia in utero is an umbilical cord blood flow interruption. Umbilical cord accident (UCA) occurs when umbilical venous or umbilical arterial blood flow is compromised to a degree that it may lead to fetal injury, weakness or death [1, 7]. There are various types of UCA including true knot, nuchal cord, body coils and abnormally long cords [2, 7, 12, 16]. True knot is a very rare occurrence in humans; a recent large study placed the occurrence of true knot at 1.2% [9]. A few cases of UCA have been reported in cetaceans [4], however, to the best of our knowledge, there were no reports on true knots of the umbilical cord. The incidence of fetal distress and MSAF was significantly higher among patients with true knots of cord [9]. The following obstetrical factors are considered as possible risk factors for true knots of the umbilical cord: abnormally long cords that may develop with increased fetal movement, hydramnios, genetic amniocentesis, gestational diabetes and male fetuses [9]. The cause and time period of umbilical knot formation were unknown in this calf. In addition, it is controversial whether true knot in the present case caused complete occlusion or not. Taking severe lipofuscin deposition in the renal tubular epithelium and systemic congestion into account, abnormal umbilical blood flow might lead to fetal malnutrition. Although the exact cause of MAS in this calf was unknown, intrauterine hypoxia due possibly to umbilical cord abnormality might have been associated with pathogenesis of meconium aspiration in the present case.

In conclusion, here, we report a case of MAS due to fetal hypoxia possibly associated with true knot of the umbilical cord in a bottlenose dolphin calf; such condition is the first case reported in calves. MAS due to perinatal asphyxia should be taken into account as a possible cause of neonatal mortality and stillbirth of calves.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso-Spilsbury M., Mota-Rojas D., Villanueva-García D., Martínez-Burnes J., Orozco H., Ramírez-Necoechea R., Mayagoitia A. L., Trujillo M. E.2005. Perinatal asphyxia pathophysiology in pig and human: a review. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 90: 1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2005.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baergen R. N., Malicki D., Behling C., Benirschke K.2001. Morbidity, mortality, and placental pathology in excessively long umbilical cords: retrospective study. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 4: 144–153. doi: 10.1007/s100240010135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benirschke K. Comparative placentation. [http://placentation.ucsd.edu]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook F., Parraga D. G., Alvaro T., Valls M., Smolensky P., Dalton L.2007. Umbilical cord accident & dolphin calf mortality. pp.181–183. In: 38th Annual International Association for Aquatic Animal Medicine Conference Proceedings.

- 5.Castro-Nájera J. A., Martínez-Burnes J., Mota-Rojas D., Cuevas-Reyes H., López A., Ramírez-Necoechea R., Gallegos-Sagredo R., Alonso-Spilsbury M.2006. Morphological changes in the lungs of meconium-stained piglets. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 18: 622–627. doi: 10.1177/104063870601800621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caswell J. L., Williams K. J.2007. Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. p. 571. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 5th ed. (Maxie, M. G. ed.), Elsevier, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins J. H.2002. Umbilical cord accidents: human studies. Semin. Perinatol. 26: 79–82(Review). doi: 10.1053/sper.2002.29860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva V. M., Carter A. M., Ambrosio C. E., Carvalho A. F., Bonatelli M., Lima M. C., Miglino M. A.2007. Placentation in dolphins from the Amazon River Basin: the Boto, Inia geoffrensis, and the Tucuxi, Sotalia fluviatilis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 5: 26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-5-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershkovitz R., Silberstein T., Sheiner E., Shoham-Vardi I., Holcberg G., Katz M., Mazor M.2001. Risk factors associated with true knots of the umbilical cord. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 98: 36–39. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(01)00312-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez A., Bildfell R.1992. Pulmonary inflammation associated with aspirated meconium and epithelial cells in calves. Vet. Pathol. 29: 104–111. doi: 10.1177/030098589202900202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norris K. S.1966. Pregnancy and parturition. pp. 297–310. In: Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises. University of California Press, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parast M. M., Crum C. P., Boyd T. K.2008. Placental histologic criteria for umbilical blood flow restriction in unexplained stillbirth. Hum. Pathol. 39: 948–953. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raju U., Sondhi V., Patnaik S.2010. Meconium aspiration syndrome: An insight. Med. J. Armed Forces India 66: 152–157. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(10)80131-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robeck T. R., Atkinson S. K. C., Brook F.2001. Reproductive abnormalities in cetaceans. pp. 218–219. In: CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine, 2nd ed. (Dierauf, L. A. and Gull, M. D. eds.), C.R.C. Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swarnam K., Soraisham A. S., Sivanandan S.2012. Advances in the management of meconium aspiration syndrome. Int. J. Pediatr. 2012: 359571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tantbirojn P., Saleemuddin A., Sirois K., Crum C. P., Boyd T. K., Tworoger S., Parast M. M.2009. Gross abnormalities of the umbilical cord: related placental histology and clinical significance. Placenta 30: 1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Elk C. E., van Dep Bildt M. W., Martina B. E., Osterhaus A. D., Kuiken T.2007. Escherichia coli septicemia associated with lack of maternally acquired immunity in a bottlenose dolphin calf. Vet. Pathol. 44: 88–92. doi: 10.1354/vp.44-1-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Ierland Y., de Beaufort A. J.2009. Why does meconium cause meconium aspiration syndrome? Current concepts of MAS pathophysiology. Early. Hum. Dev. 85: 617–620. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]