ABSTRACT

Feline pituitary tumors are rare. An 8-year-old male Japanese domestic cat presented with anorexia and emaciation. The cat died 17 days after admission from progressive neurological symptoms. At necropsy, a pituitary tumor measuring 25 × 18 × 15 mm was found. Microscopically, the tumor was divided into multiple lobules and had grown invasively into the adjacent brain tissue and sphenoid bone. Tumor cells had pleomorphic nuclei with prominent centrally located nucleoli and abundant amphophilic polygonal cytoplasm. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells stained with anti-adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), α-melanin-stimulating hormone (MSH) and β-endorphin antibodies. Ultrastructurally, the cytoplasm of the tumor cells contained various sized secretory granules. Based on these pathological findings, this tumor was diagnosed as pituitary carcinoma originated from pars intermedia cells.

Keywords: feline, pars intermedia, pituitary carcinoma, pituitary gland.

Brain tumors are rare in cats [14, 22]. The most commonly seen brain tumors in cats are meningioma and lymphoma, which account for 75% of all feline brain tumors [16]. Pituitary tumors occur in only 9.3% of cats affected with brain tumors and may manifest with endocrine or neurological symptoms, such as ataxia, circling and seizure, which may occur depending on the location of the tumor [16]. About 18% of feline pituitary tumors are found accidentally at postmortem examination, which indicates the difficulty in diagnosing this disease [16]. In dogs, pituitary-dependent hypercortisolism (PDH) is a common disease. The causative adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-producing tumor in the adenohypophysis may arise from either the anterior lobe or the pars intermedia [1]. In cats, pituitary tumors with PDH are rare and are usually associated with diabetes mellitus [12]. To the authors’ knowledge, the concomitant presence of pituitary carcinoma and PDH without diabetes mellitus has not been reported.

An 8-year-old, castrated male Japanese domestic cat, weighing 3.7 kg, was referred to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital of Kitasato University for detailed examination of unexplained anorexia and weight loss. The cat had been treated by a local veterinarian for 1 month before visiting us, but the condition had not been ameliorated by palliative care. The owner also noted a seizure-like episode during this period. At the first admission to our hospital, the cat showed neurological symptoms, such as depression, head tilt, ataxia and circling to the right side. Upon physical examination, asymmetrical pupil dilation was also noted. Pulse (156 beats per min), respiration (78 breaths per min), body temperature (38.6°C) and other physical findings were considered normal.

A complete blood count included band neutrophils(0/µl), segmented neutrophils (24,284/µl), lymphocytes (650/µl), monocytes (1,040/µl), eosinophils (0/µl) and basophils (0/µl). These results suggested eosinopenia and a classic stress leukogram. Plasma biochemistry showed high blood glucose (345 mg/dl, reference 70–110 mg/dl) and low potassium (2.22 mEq/l, reference 3.5–5.0 mEq/l) levels. Other biochemical parameters were within the normal range. Urinalysis was performed on a sample obtained by bladder puncture. The urine had a specific gravity of 1.041 (reference 1.035–1.060) and pH 6.3 (reference 5.0–9.0). Excretion of glucose (500–1,000 mg/dl) and protein (30–100 mg/dl) into the urine was noted using a dipstick.

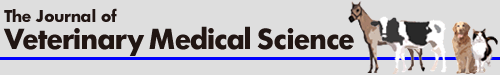

Abdominal ultrasound revealed bilateral enlargement of the adrenal glands. Based on these findings, we speculated that the cat had a pituitary–adrenal axis abnormality, and therefore, the cat was hospitalized for further neurological and endocrine examinations. Computed tomography (CT) was performed on the cat under anesthesia with isoflurane in oxygen. Transverse contrast-enhanced CT images of the brain revealed a large ovoid-shaped mass in the area of the pituitary gland (Fig. 1). The mass appeared to be hyperintense compared with the surrounding parenchyma, and the signal for this area was enhanced further by bolus intravenous administration of the iodinated contrast agent iohexol (1 ml/kg). There was no sign of edema around the mass. The maximum width and height of the mass were 18.6 and 10.4 mm, respectively. The mass in the hypophyseal fossa matched the characteristics of previously reported pituitary tumors [18], and therefore, this case was tentatively diagnosed as a pituitary macroadenoma.

Fig. 1.

An enlarged pituitary mass (arrows) is seen in the pituitary fossa by CT. Bar=1 cm.

The integrity of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenocortical system was assessed by a series of endocrine examinations. A high-dose dexamethasone suppression test was performed by intravenous administration of dexamethasone (DEX, 1 mg/kg) in the morning. Plasma was obtained for measurement of cortisol concentration before, and 4 and 8 hr after administration of DEX. The results showed a maximum 76% suppression at 4 hr after DEX injection compared with the basal cortisol concentration of 13.1 µg/ml.

The plasma concentrations of the following endogenous hormones were also measured: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), ACTH, growth hormone (GH) and antidiuretic hormone (ADH). The plasma concentrations of TSH (0.93 ng/ml), GH (1.3 ng/ml) and ADH (6.4 pg/ml) were within the normal ranges. By contrast, the plasma concentration of ACTH of 472 pg/ml far exceeded the physiological range. On the basis of these endocrine findings, the present case was diagnosed as PDH.

During hospitalization, the cat was treated continuously by intravenous potassium-supplemented fluid administration to correct dehydration and hypokalemia. A nasogastric tube was placed to force-feed the cat with high-caloric liquid formula for anorexia. However, further treatments, such as surgery or radiation therapy, were not desired by the owner. The cat showed progressive morbidity and died on day 17 of hospitalization.

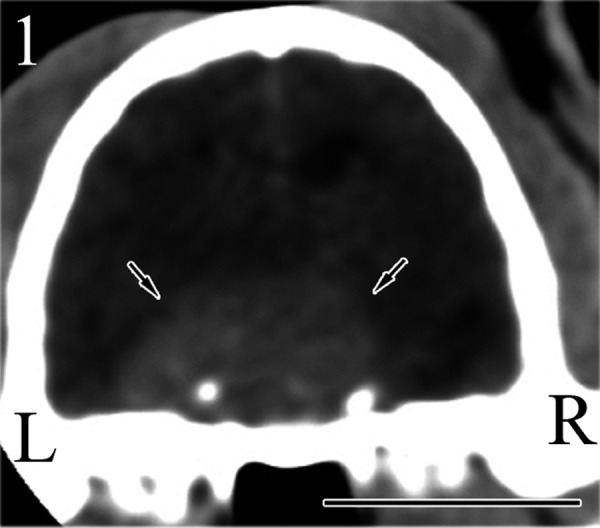

At necropsy, a tumor, measuring 25 mm (length) × 18 mm (width) × 15 mm (height), was found in the region of the pituitary gland (Fig. 2). The tumor had increased hardness compared with the surrounding parenchyma and had completely replaced the pituitary gland. The borders between the tumor and brain were not clear. The tumor compressed the overlying hypothalamus and the thalamus, midbrain and brain stem. The lateral ventricle was dilated. Both adrenal glands (left, 15 × 7 mm; right, 25 × 6 mm) were enlarged. The lungs were edematous and congested. The thyroid glands and parathyroid glands were normal in shape and size.

Fig. 2.

Sagittal section showing the mass in the region of the pituitary gland (arrows). The borders between the tumor and brain are not clear. Bar=2 cm.

The pituitary gland tumor and brain, adrenal glands, kidney, liver, spleen, lung, thyroid glands and parathyroid glands were examined histopathologically. All samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. All sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). The pituitary tumor was also prepared for staining with Masson’s trichrome, reticulin silver impregnation, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and immunohistochemistry. A normal pituitary gland of another cat was used as the control for immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemical examinations were performed using the streptavidin-biotin peroxidase method with commercial kits (Nichirei Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The following primary antibodies were used: cytokeratin (CK) (Clone AE1/AE3; Dako-Japan, Kyoto, Japan; 1:50), ACTH (Clone 18–0087; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA, U.S.A; 1:50), α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) (Clone DS-040398; Progen Biotechnik, GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany; 1:1,000), β-endorphin (H-022–33; Phoenix, Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, CA, U.S.A; 1:500), GH (Clone A572/R4H; Biogenesis, Poole, U.K.; 1:400), luteinizing hormone (LH) (Clone 410M; Biomeda, Foster, CA, U.S.A; prediluted), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (Clone 411M; Biomeda; prediluted), prolactin (Clone 413M; Biomeda; prediluted), Ki-67 (Clone MIB-1; Dako-Japan; prediluted) and proliferating cell nuclear antigens (PCNA) (Clone PC10; Dako-Japan; prediluted).

To investigate the possible correlations between the Ki-67 and PCNA labeling indexes (LIs) and their clinicobiological variables, Ki-67- and PCNA-positive nucleoli were scored by counting at least 1,000 cells in representative × 400 high-power fields. The percentages of positively stained cells were recorded as the Ki-67 and PCNA LIs. For electron microscopic examination, the formalin-fixed pituitary gland tumor was cut into 1 mm blocks, fixed in 1% buffered osmium tetroxide and embedded in epoxy resin. Sections of about 70 nm in thickness were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined using a transmission electron microscope (H-7650, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

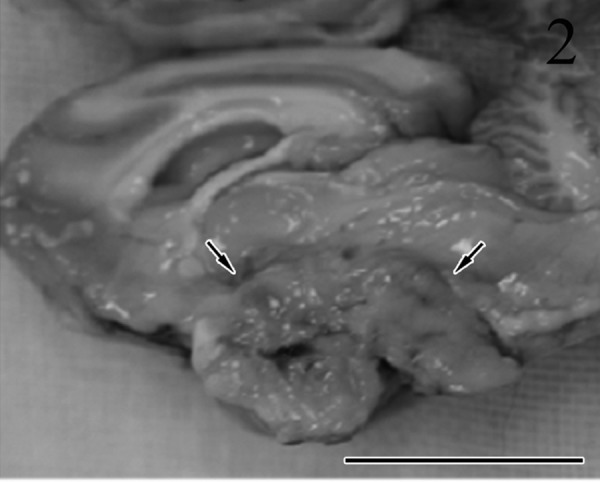

Microscopically, the tumor was not encapsulated and had grown invasively into the adjacent brain tissue (Fig. 3) and sphenoid bone. The tumor caused massive destruction of the adjacent hypothalamus and midbrain structures, and many vacuolated nerve fibers and fragmentation of axons were observed in the white matter tracts. The tumor had lobular, trabecular, alveolar (Fig. 4) and adenoid patterns with multifocal necrosis and had invaded the blood vessels. The adenoid structures were sometimes filled by eosinophilic colloidal material (Fig. 5) and were PAS positive. The tumor cells showed prominent nuclear pleomorphism and anisokaryosis. The nucleoli were large and centrally located. The amount of cytoplasm in the tumor cells was variable, and the cytoplasm was slightly basophilic. Evidence of frequent mitosis was observed (1–7 per × 400 high-power field). Occasionally, multinuclear giant cells and atypical cells with intranuclear eosinophilic pseudoinclusions (Fig. 6) were also observed. In the stromal area, evidence of connective tissue was prominent, and these areas stained positively with Masson’s trichrome and reticulin silver impregnation. Other histopathological findings included bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasia in the region of the zona glomerulosa and zona fasciculata. There were no pathological changes in other organs including the parathyroid and thyroid glands. Distant metastasis of the tumor cells was not observed.

Fig. 3.

The tumor (T) is not encapsulated, and tumor cells have grown invasively into the adjacent brain (*) tissue. HE. Bar=50 µm.

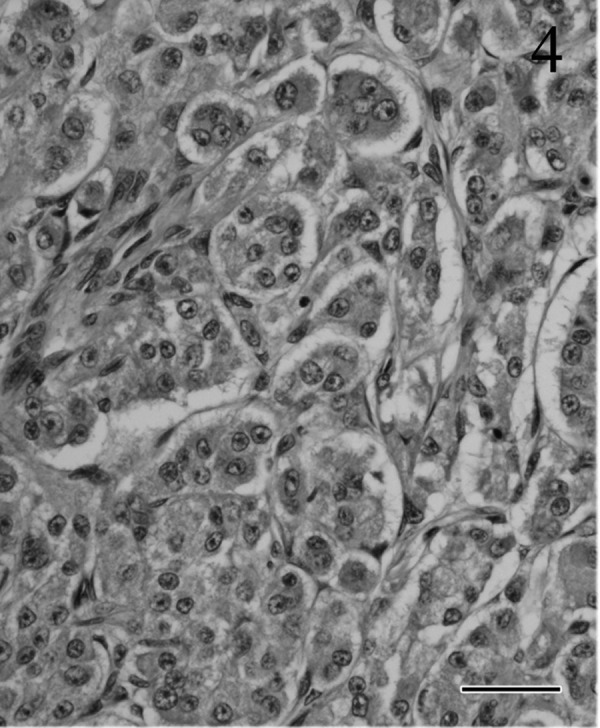

Fig. 4.

Tumor cell proliferation in alveolar patterns surrounded by vascular connective tissue. Atypical nucleoli are located centrally; the abundant cytoplasm is pale and basophilic. HE. Bar=30 µm.

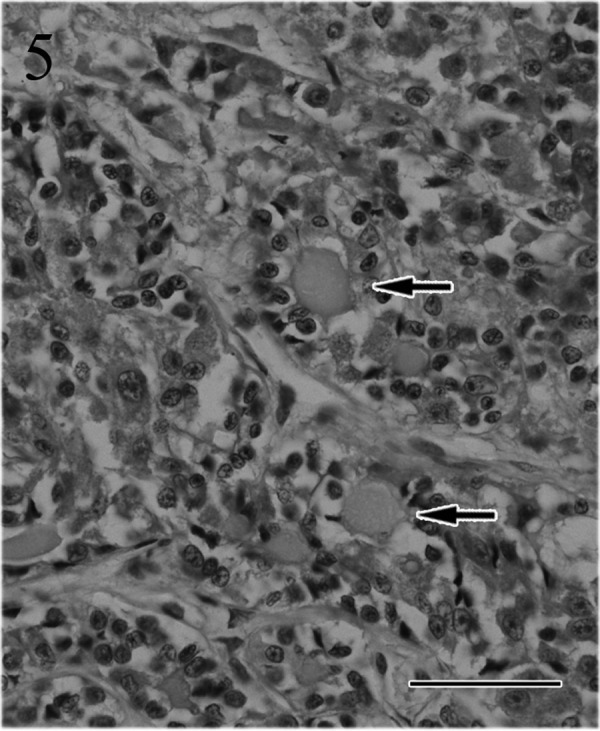

Fig. 5.

The tubular or adenoid structures are filled by colloid materials (arrows). HE. Bar=50 µm.

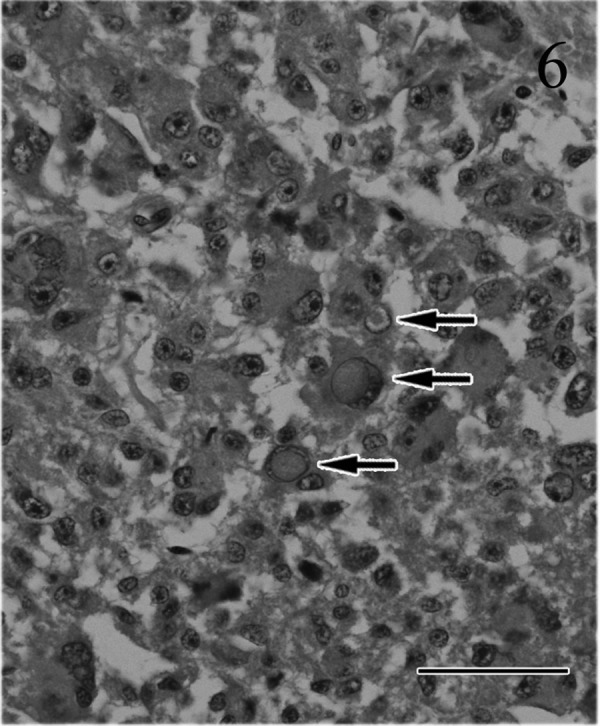

Fig. 6.

Most tumor cells have atypical nuclei with large nucleoli and abundant, slightly basophilic cytoplasm. Occasionally, multinuclear giant cells and intranuclear eosinophilic pseudoinclusions (arrows) are observed. HE. Bar=50 µm.

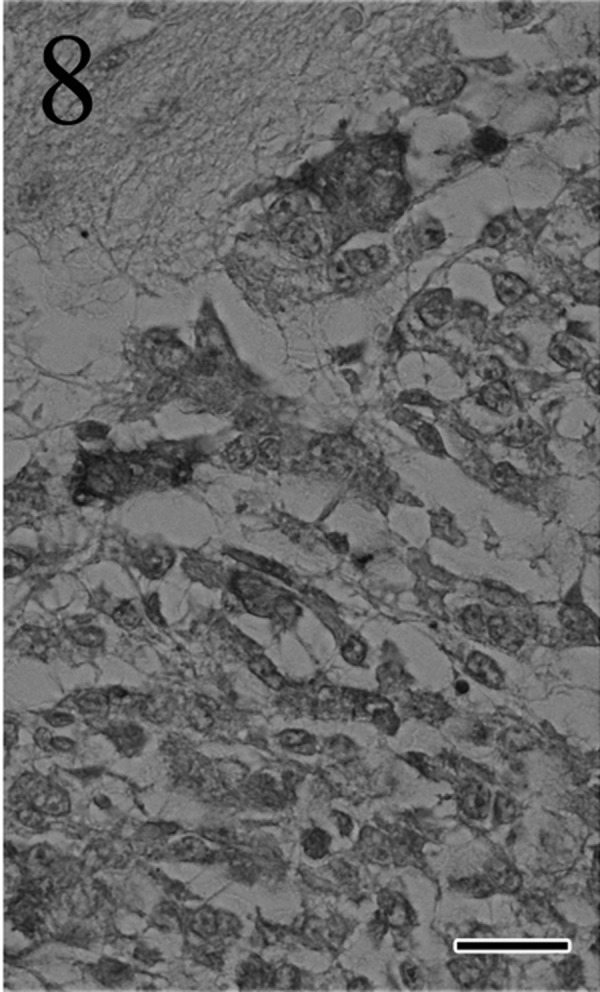

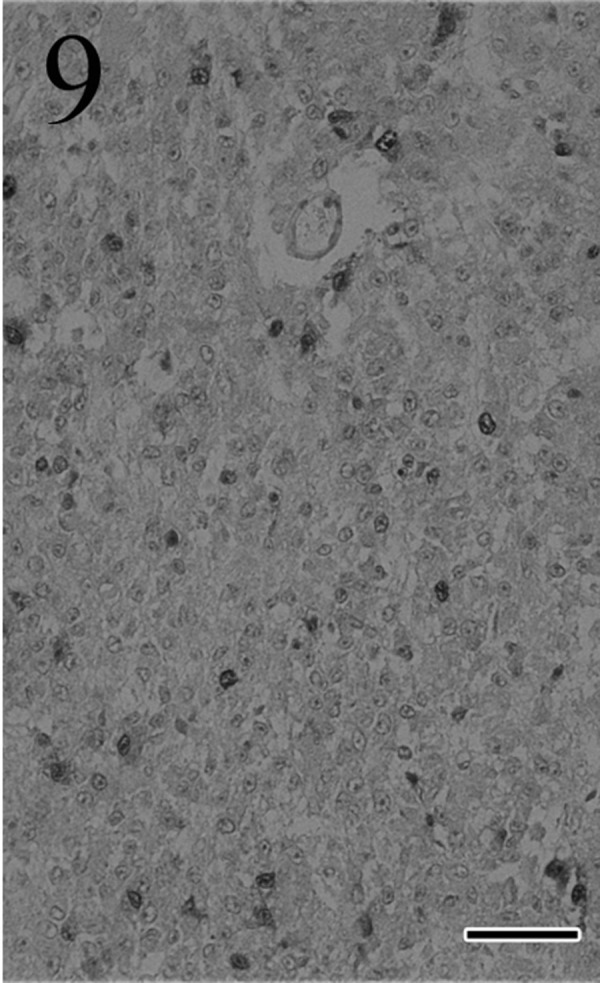

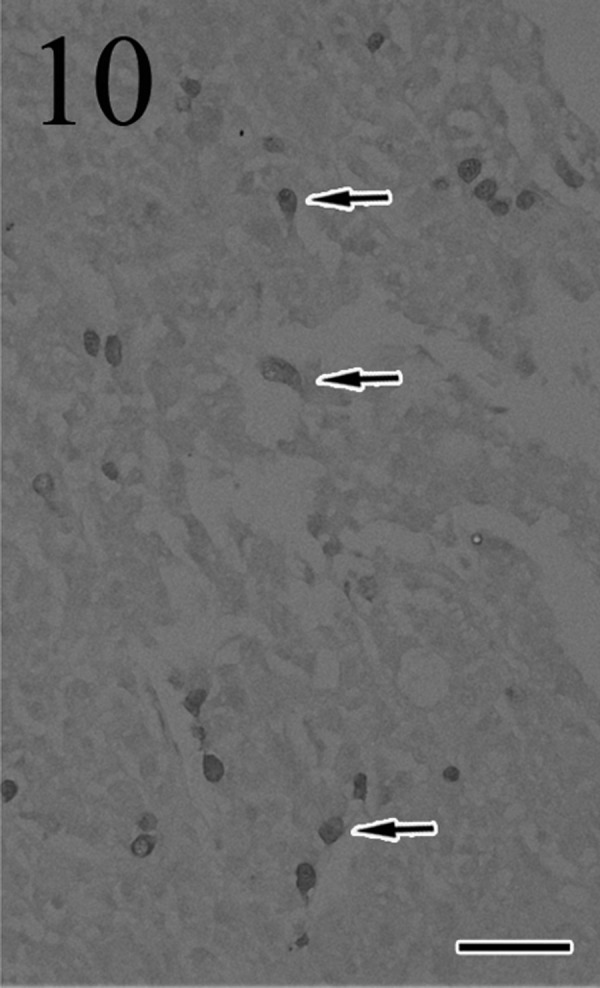

Immunohistochemically, most of the tumor cells were positive for ACTH (Fig. 7), α-MSH (Fig. 8), β-endorphin and CK AE1/AE3 antibodies. These positive staining patterns were similar to those of the pars intermedia cells of normal pituitary gland of cat used as a positive control. By contrast, few tumor cells were positive for LH, FSH and prolactin. The mean LIs were 35% for PCNA (Fig. 9) and 8% for Ki-67 (Fig. 10); by contrast, the mean percentage of cells positive for each antibody was<1% in the normal pituitary gland.

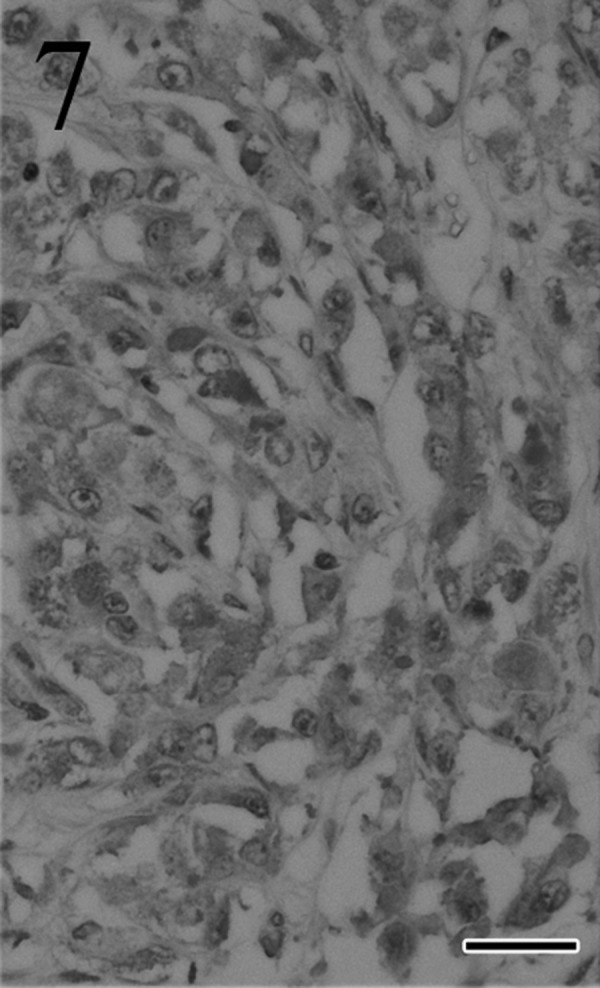

Fig. 7.

Most tumor cells stain positively for ACTH. Immunohistochemistry. Bar=25 µm.

Fig. 8.

Many tumor cells are positive for α-MSH. Immunohistochemistry. Bar=25 µm.

Fig. 9.

Many tumor cells are positive for PCNA. Immunohistochemistry. Bar=50 µm.

Fig. 10.

Many tumor cells are positive (arrows) for Ki-67. Immunohistochemistry. Bar=50 µm.

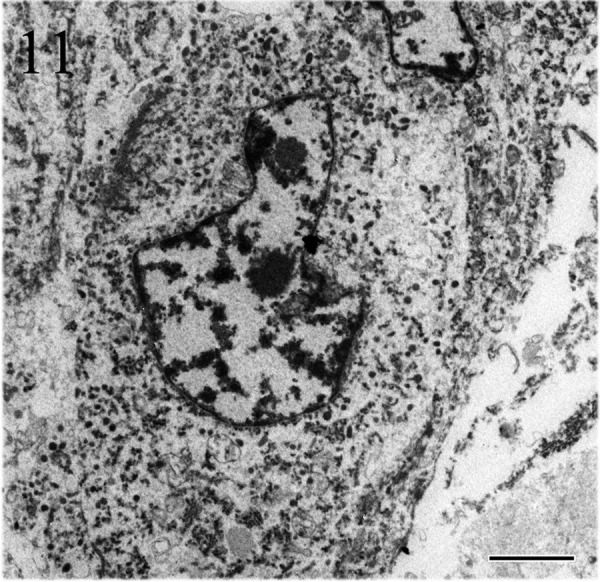

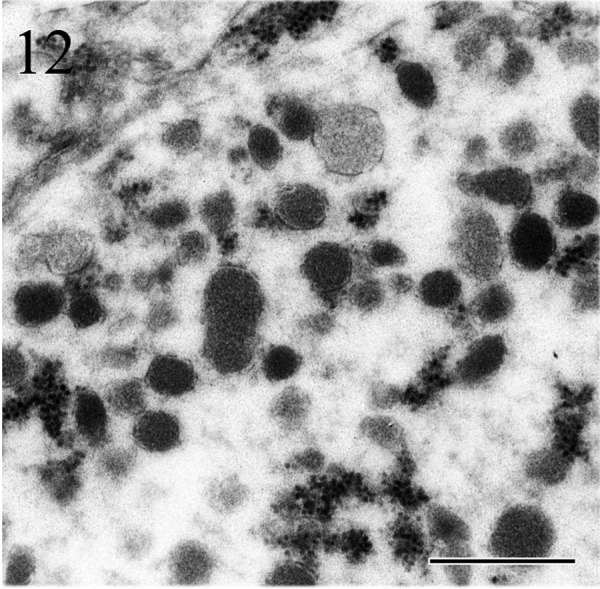

Ultrastructurally, the tumor cells showed nuclear pleomorphism and often had deeply invaginated nuclei. The cytoplasm comprised abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria and secretory granules (Fig. 11) of various sizes. The diameters of secretory granules were in the range of 100–300 nm (Fig. 12).

Figs. 11 and 12.

Tumor cells have prominent nucleoli, deeply invaginated nuclei and cytoplasm filled with secretory granules. The diameter of secretory granules is in the range of 100–300 nm. Electron microscopy. Bars=2 µm (Fig. 11) and 500 nm (Fig. 12).

Hypercortisolism is an endocrine disorder caused by elevated production of cortisol by the adrenal cortex. Cats with hypercortisolism frequently present with characteristic clinical signs, such as cutaneous atrophy, polyphagia, polyuria, obesity, muscle weakness and recurrent urinary tract infections [3]. However, this cat showed suppressive neurological symptoms, such as depression and anorexia, both of which were most likely caused by the pituitary tumor growth [13]. Hyperglycemia caused by the gluconeogenic action of cortisol is a common finding in feline hypercortisolism. Prolonged hyperglycemia triggers insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and as many as 80% of cats with hypercortisolism also have secondary diabetes mellitus [11]. Therefore, there is a strong link between hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus in cats with hypercortisolism. In the current case, hyperglycemia and glucosuria were confirmed on the first day of admission, but long-term hyperglycemia was not confirmed because of the normal level of blood fructosamine, a long-term index of blood glucose. These results indicated that although there was no overtly prolonged hyperglycemia, the cat may have been at least in the prediabetic state.

In the present case, CT images showed a large single space occupying tumor located in the pituitary fossa, which extended into the parenchyma of the brain. Although the anatomical site and CT features of the lesion were highly suggestive of a pituitary tumor or a sellar meningioma, clinical findings including plasma biochemistry and a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test excluded the possibility of a meningioma.

Pituitary carcinomas are very rare in cats. Generally, the distinction between a pituitary carcinoma and an adenoma is made on the basis of extensive invasion into the brain, sphenoid bone, blood vessels and distant metastasis. However, the differential diagnosis between adenoma and carcinoma is sometimes difficult and confusing in animals. Ki-67 and PCNA, markers of cell proliferation, are used widely to predict tumor behavior and surgical outcomes [6, 17]. In humans, the mean Ki-67 LIs for noninvasive pituitary adenoma, invasive pituitary adenoma and pituitary carcinoma were reported as 1.37% ± 0.15%, 4.66% ± 0.57% and 11.91% ± 3.41%, respectively [15]. In pituitary adenomas in dogs, Ki-67 and PCNA LIs were reported as 8.4% ± 14.2% and 35.5% ± 12.2%, respectively [19]. The ranges of Ki-67 and PCNA LIs in these reports are wide, and the expression of these makers has not been investigated in feline pituitary tumors. Nevertheless, in our case, all of the histopathology and immunohistochemistry results were consistent with malignant properties.

In the present case, the tumor cells sometimes had intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions. These intranuclear inclusions are found in not only pituitary tumors [20] but also other tumors including meningioma [21], paraganglioma [4], phenochromocytoma [4] and thyroid carcinoma [8] in humans. Intranuclear inclusions in pituitary tumors are formed by cytoplasmic invagination and composed of cytoplasmic organelles, such as rough endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus and the secretory granules [20]. In addition, it was reported that there are no significant differences in the frequency of the intranuclear inclusions between the functional and non-functional pituitary tumors [20]. To our best knowledge, there is no report about intranuclear inclusions in pituitary tumors in cats. Therefore, further data collection is needed to better understand the relationship between intranuclear inclusions and hormonal status or malignancy of the pituitary tumor in cats.

Pituitary tumors in horses almost arise from the pars intermedia and manifest as hyperglycemia and adrenal cortical hyperplasia. In the dog, pars intermedia tumors contain ACTH and α-MSH, and excessive secretion of ACTH leads to bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasia [2, 5]. In the present case, most of tumors cells stained positively for ACTH, α-MSH and β-endorphin in their cytoplasm [7, 9, 10]. α-MSH, a peptide hormone, is derived from proopiomelanocortin processing in the pars intermedia cells and is thought to be a marker of pars intermedia cells. Although we did not measure the plasma α-MSH concentration in the present study, the clinical signs, the histopathology and immunohistochemistry results suggested that the tumor originated from pars intermedia cells. The rapid growth of the pituitary carcinoma with massive destruction of the brain, rather than endocrine dysfunction, seemed to be the major cause of the neurological signs and death.

REFERENCES

- 1.Capen C. C.2002. Tumors of the endocrine glands. p. 610. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, 4th ed. (Meuten J. D. ed.), Iowa State Press, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capen C. C., Martin S. L., Koestner A.1967. Neoplasm in the adenohypophysis of dogs. Pathol. Vet. 4: 301–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiaramonte D., Greco D. S.2007. Feline adrenal disorders. Clin. Tech. Small Anim. Pract. 22: 26–31. doi: 10.1053/j.ctsap.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeLellis R. A., Suchow E., Wolfe H. J.1980. Ultrastructure of nuclear “inclusions” in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Hum. Pathol. 11: 205–207. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(80)80147-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Etreby M. F., Müller-Peddinghaus R., Bhargava A. S., Trautwein G.1980. Functional morphology of spontaneous hyperplastic and neoplastic lesions in the canine pituitary gland. Vet. Pathol. 17: 109–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerdes J., Lemke H., Baisch H., Wacker H. H., Schwab U., Stein H.1984. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J. Immunol. 133: 1710–1715 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinrichs M., Baumgärtner W., Capen C. C.1990. Immunocytochemical demonstration of proopiomelanocortin-derived peptides in pituitary adenomas of the pars intermedia in horses. Vet. Pathol. 27: 419–425. doi: 10.1177/030098589902700606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaneko C., Shamoto M., Niimi H., Osada A., Shimizu M., Shinzato M.1996. Studies on intranuclear inclusions and nuclear grooves in papillary thyroid cancer by light, scanning electron and transmission electron microscopy. Acta Cytol. 40: 417–422. doi: 10.1159/000333892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeb W. F., Capen C. C., Johnson L. E.1966. Adenomas of the pars intermedia associated with hyperglycemia and glycosuria in two horses. Cornell Vet. 56: 623–639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meij B. P., van der Vlugt-Meijer R. H., van den Ingh T. S., Flik G., Rijnberk A.2005. Melanotroph pituitary adenoma in a cat with diabetes mellitus. Vet. Pathol. 42: 92–97. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-1-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols R.1997. Complications and concurrent disease associated with diabetes mellitus. Semin. Vet. Med. Surg. Small Anim. 12: 263–267. doi: 10.1016/S1096-2867(97)80019-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson M. E., Taylor R. S., Greco D. S., Nelson R. W., Randolph J. F., Foodman M. S., Moroff S. D., Morrison S. A., Lothrop C. D.1990. Acromegaly in 14 cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 4: 192–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1990.tb00897.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skelly B. J., Petrus D., Nicholls P. K.2003. Use of trilostane for the treatment of pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism in a cat. J. Small Anim. Pract. 44: 269–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2003.tb00154.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solleveld H. A.1986. Brain tumors in man and animals: report of a workshop. Environ. Health Perspect. 68: 155–173. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8668155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thapar K., Kovacs K., Scheithauer B. W., Stefaneanu L., Horvath E., Pernicone P. J., Murray D., Laws E. R.1996. Proliferative activity and invasiveness among pituitary adenomas and carcinomas: an analysis using the MIB-1 antibody. Neurosurgery 38: 99–106. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199601000-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Troxel M. T., Vite C. H., van Winkle T. J., Newton A. L., Tiches D., Dayrell-Hart B., Kapatkin A. S., Shofer F. S., Steinberg S. A.2003. Feline intracranial neoplasia: retrospective review of 160 cases (1985–2001). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 17: 850–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner H. E., Wass J. A.1999. Are markers of proliferation valuable in the histological assessment of pituitary tumours? Pituitary 1: 147–151. doi: 10.1023/A:1009979128608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turrel J. M., Fike J. R., Le Couteur R. A., Higgins R. J.1986. Computed tomographic characteristics of primary brain tumors in 50 dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 188: 851–856 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Rijn S. J., Grinwis G. C., Penning L. C., Meij B. P.2010. Expression of Ki-67, PCNA, and p27kip1 in canine pituitary corticotroph adenomas. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 38: 244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang S. W., Yang K. M., Kang H. Y., Kim T. S.2003. Intranuclear cytoplasmic pseudoinclusions in pituitary adenomas. Yonsei Med. J. 44: 816–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida T., Hirato J., Sasaki A., Yokoo H., Nakazato Y., Kurachi H.1999. Intranuclear inclusions of meningioma associated with abnormal cytoskeletal protein expression. Brain Tumor Pathol. 16: 86–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02478908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaki F. A., Hurvitz A. I.1976. Spontaneous neoplasms of the central nervous system of the cat. J. Small Anim. Pract. 17: 773–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1976.tb06943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]