Abstract

The photolytic formation of thiyl radicals allows for the selective detection of total homocysteine (tHcy) in plasma after reduction and filtering. The mechanism is based on the reduction of viologens by the α-amino carbon centred radical of Hcy generated by intramolecular hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) of its thiyl radical.

Several major pathologies including cardiovascular disease (CVD), dementia, osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s disease are associated with elevated levels of plasma tHcy.1,2 Significant research has shown that Hcy is a risk factor at even modestly elevated levels.3 Published evidence that shows an association between hyperhomosysteinemia (> 12 µM tHcy)4 and major diseases renders its determination of clinical significance.5

Current commercial Hcy detection methods use separations, relatively fragile and expensive enzymatic or immunogenic materials and complex instrumentation.3, 6, 7 Thus, there is need to develop selective, yet simple and inexpensive methods that can be used at point of care diagnostics to facilitate the diagnosis and treatment of related diseases. Available kits generally use multi-step washing procedures and/or specialized storage below −20 °C limiting their use in emerging nations with limited access to refrigeration or electricity. Moreover, even in developed countries point-of-care and kit-based assays are of interest considering rising health care costs and increasing interest in patient-based monitoring.

A wide variety of useful detection probes for biological thiols have been reported.8, 9 Most have no specificity for Hcy over other related analytes such as cysteine (Cys) and glutathione (GSH). The Cys levels in human plasma from healthy individuals range from 135.8 to 266.5 µM.10 Consequently, they complicate the determination of plasma tHcy levels. Though some chemosensors or chemodosimiters that selectively respond to Hcy over Cys and other thiols have been reported, they are typically tested at equimolar, rather than more natural ca. 20-fold excess Cys concentrations.11

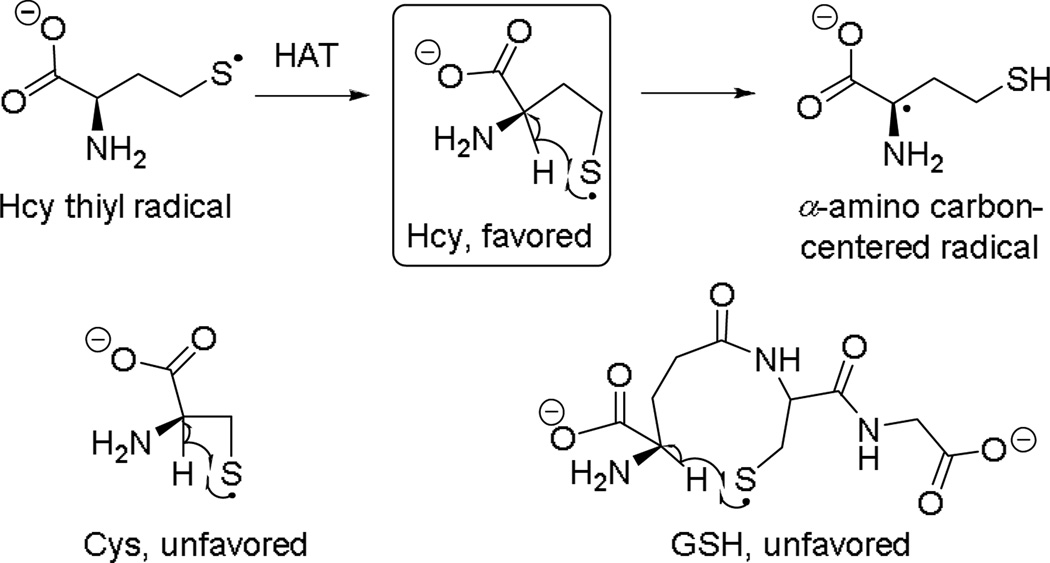

In 2004, we developed a selective colorimetric method for the detection of Hcy based on the kinetically-favored formation of α-amino carbon centred radical for Hcy via a reversible intramolecular hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) with the corresponding thiyl radical.12 This is attributed to favored formation of a 5-membered ring in the transition state, as opposed to 4- and 9-membered ring configurations for Cys and GSH, respectively (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Kinetically favored HAT reaction for Hcy.

The mechanism shown in Scheme 1 was initially proposed and studied by Zhao et al., under basic conditions (pH 10.5).13 Azide radical was used to oxidize thiols and the formation of reducing radicals was monitored through the UV-Vis absorption spectra via production of the reduced methyl viologen radical cation (MV•+). Under the highly basic conditions investigated by Zhao et al., no colorimetric selectivity between GSH, Cys and Hcy was observed. This was due to the presence of significant amounts of thiolate anion promoting the formation of a reducing disulfide radical anion that also reacts with methyl viologen (MV2+) independently of the HAT mechanism. Conversely, neutral conditions investigated by us diminish thiolate formation, thereby enabling selective detection of Hcy in human blood plasma via its reducing carbon radical (Scheme 1).12,14 A protocol for visual detection of Hcy was developed based on this method wherein the Hcy thiyl radical is generated by heat.15 The colorimetric method was investigated using human serum calibration standards (NIST SRM 1955), and successfully distinguished micromolar concentration differences (3.79, 6.13, 13.4 and 38.73 µM) of tHcy visually using MV2+.8 The assay protocol involved no sample processing. It only required a two-fold dilution, addition of MV2+ and tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) and 2 min heating at reflux.

The basis of this current work is the hypothesis that photolytic methods would afford analogous selectivity via the intramolecular HAT mechanism while enabling the assay to be carried out at room temperature. Johnson and co-workers reported the photochemical reduction of viologens in ethanolic solutions.16 A mechanism based on the abstraction of a methylene hydrogen atom from EtOH to form a free radical that reduced the viologen in direct sunlight was proposed. We envisioned that this approach could be compatible with our HAT mechanism for Hcy via photolytic, rather than thermal generation of the Hcy thiyl radical. Our hypothesis was confirmed by exposing solutions of thiols and MV2+ in Tris buffer at neutral pH to direct sunlight at room temperature. A blue color was observed within 2 minutes in the Hcy sample while other thiols solutions remained unchanged (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Response of MV2+ towards various thiols upon exposure to direct sunlight. Solutions of MV2+ (50 mM) were mixed with thiols (20 µM) in 0.5 M Tris buffer at pH 7, saturated with argon and exposed to sunlight. Pictures were taken 2 min after exposure to sunlight.

To create a laboratory test, we reasoned that an appropriate light source to generate the thiyl radical should emit around 325 nm based on the reported S-H bond dissociation energy of Cys of 370 kJ/mol.17 To this end, we selected a very simple and inexpensive compact fluorescent lamp emitting in this region, Reptisun™ consisting of 10% UVB and 30% UVA. The photolysis experiments were performed using this lamp with a light intensity of 6.85 mW/cm2 as measured by a Melles Griot Broadband Power/Energy Meter 13PEM001. We were able to detect Hcy selectively in human blood plasma using MV2+ without any interference from Cys and GSH in the range of their physiological concentrations. Upon irradiation of plasma samples spiked with various biothiols, only the Hcy (15 µM) spiked sample showed significant absorption response whereas Cys and GSH remained unchanged. The absorption spectra are shown in Fig. S1, ESI†.

In previous studies, benzyl viologen (BV2+), a significantly less toxic chromogen than MV2+, was found to be more reactive towards the Hcy α-amino carbon-centred radical than MV2+ under thermal conditions. BV2+ has a higher reduction potential (−370 mV) compared to MV2+ (−446 mV).18 Hence we investigated the response of BV2+ to Hcy and other thiols using the photochemical method.

BV2+ indeed displayed selectivity towards Hcy under the new photolytic conditions compared to structurally related thiols (Fig. 2). Moreover, changing the chromogen allowed us to lower its concentration from 50 mM (MV2+) to 20 mM (BV2+). In addition, the Hcy response was greater as compared to photolysis in the presence of MV2+. An irradiation time of 15 min afforded optimal selectivity and response.

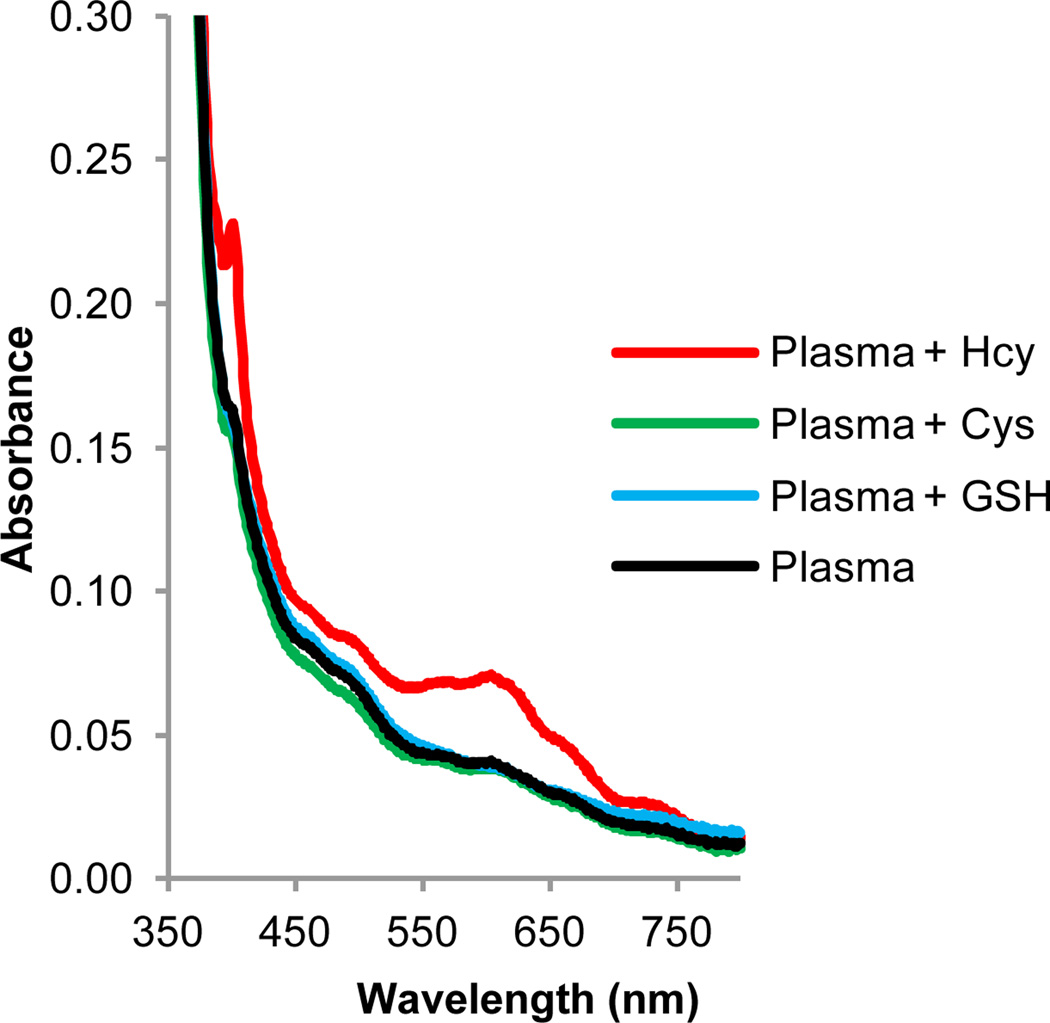

Fig. 2.

Spectral response of BV2+ towards various spiked thiols in human blood plasma upon irradiation. Absorption spectra of solutions of BV2+ (20 mM) in human blood plasma and 0.5 M Tris buffer (pH 7.0) spiked with 1.5 µM Hcy, 25 µM Cys and 0.6 µM GSH. Plasma (10% v/v) was added to an argon-saturated solution of viologen, thiol & buffer and irradiated for 15 min using a Reptisun™ lamp.

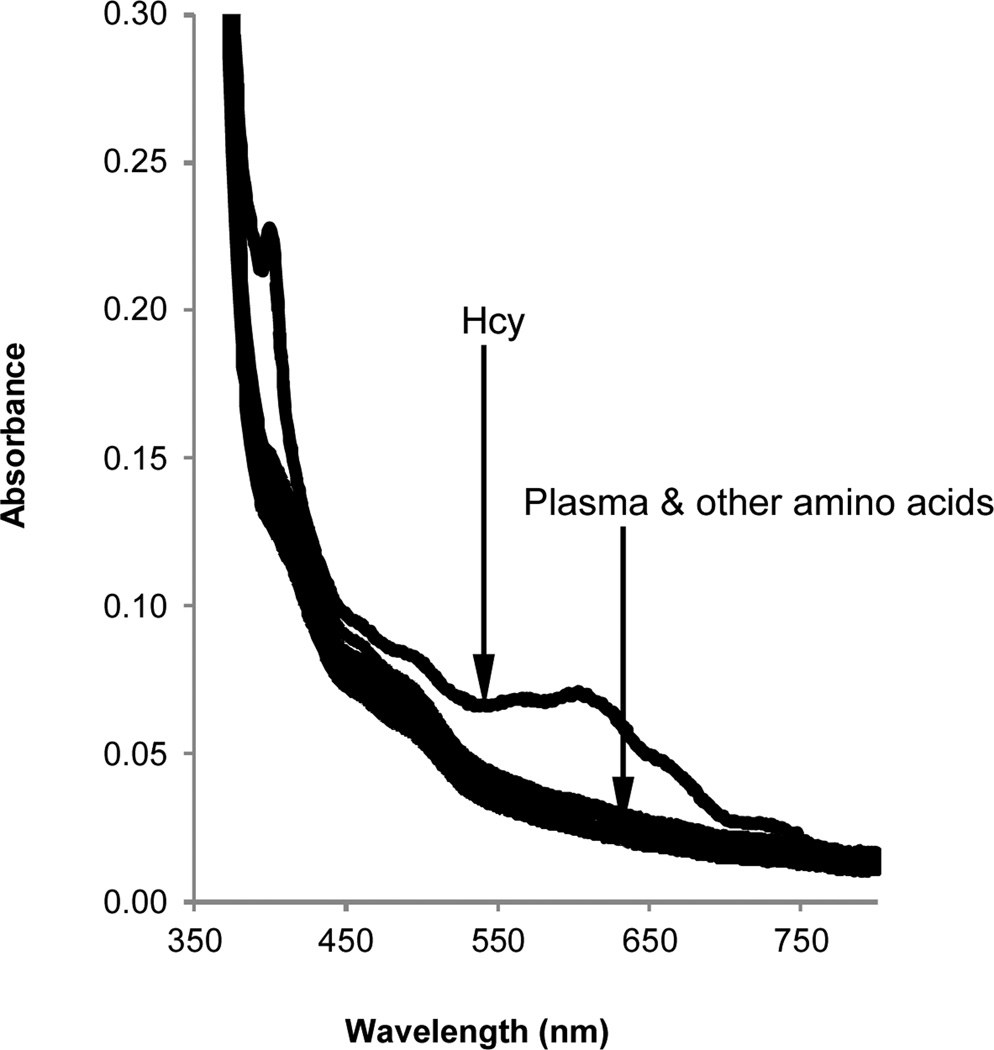

A selective response of BV2+ to Hcy in human plasma was observed after reduction using immobilized tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP gel), centrifugation and spiking with various thiols (Fig. S2, ESI†).

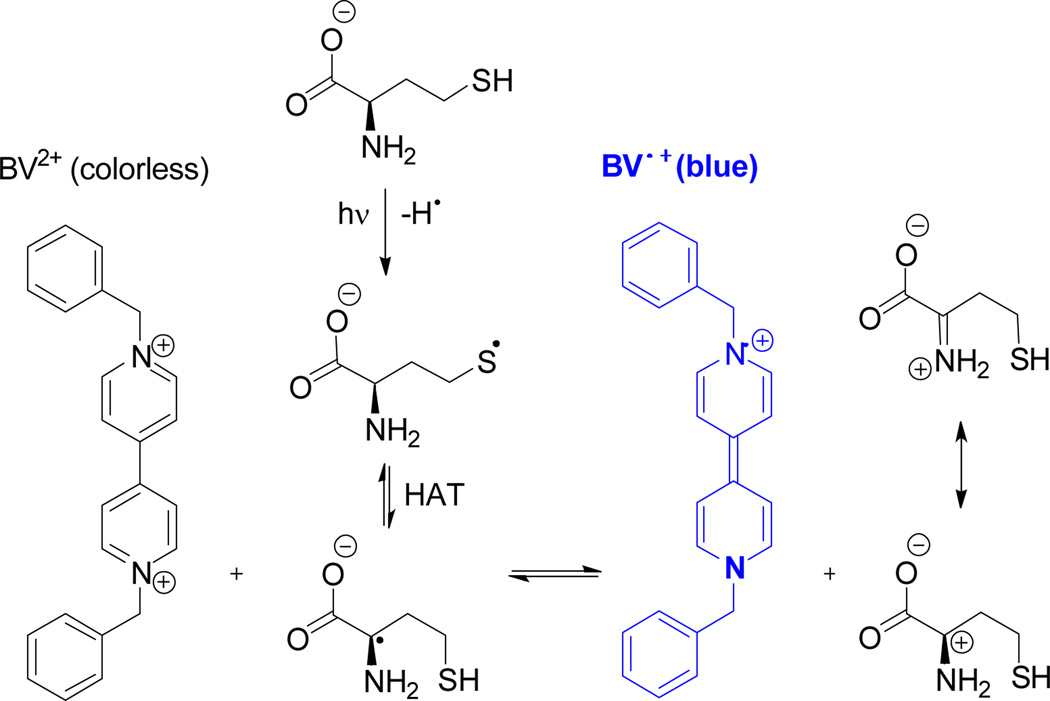

The proposed mechanism is analogous to the thermal reaction for the selective detection of Hcy we have previously reported.14 It involves the generation of the Hcy thiyl radical by photolysis followed by the HAT reaction to form the α-amino carbon centred radical that in turn, reduces BV2+ to its corresponding radical cation (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Mechanism for the detection of Hcy involving three steps: (i) photolytic generation of Hcy thiyl radical, (ii) hydrogen atom transfer turning the thiyl radical into a α-amino carbon-centred radical, (iii) reduction of BV2+.

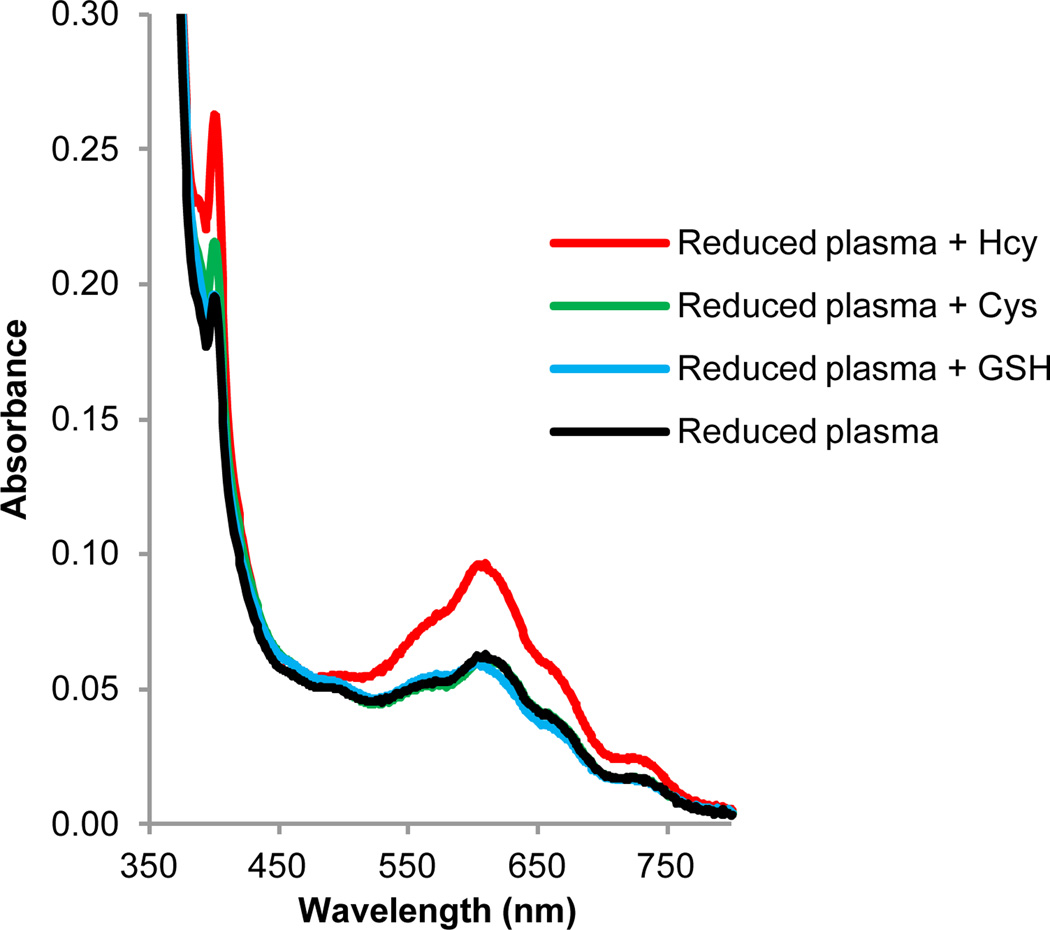

We optimized the sample processing by replacing the centrifugation step with a simple filtration of the sample through 0.45 µm PVDF filter vials. The spectral response and selectivity was comparable in both methods and excellent selectivity towards tHcy was observed (Fig.3). Interestingly, the use of filters improved the overall background interference from the plasma components.

Fig. 3.

Spectral response of BV2+ towards various spiked thiols in reduced human plasma upon irradiation. Absorption spectra of solutions of BV2+ (20 mM) in reduced human blood plasma and 0.5 M Tris buffer (pH 7.0) spiked with 1.5 µM Hcy, 25 µM Cys and 0.6 µM GSH. Plasma was incubated for 1 h with TCEP Gel followed by filtration using a Single StEP™ 0.45 µm PVDF filter vial. The reduced, filtered plasma (10% v/v) was added to an argon-saturated solution of viologen, thiol and buffer and irradiated for 15 min using a Reptisun™ lamp.

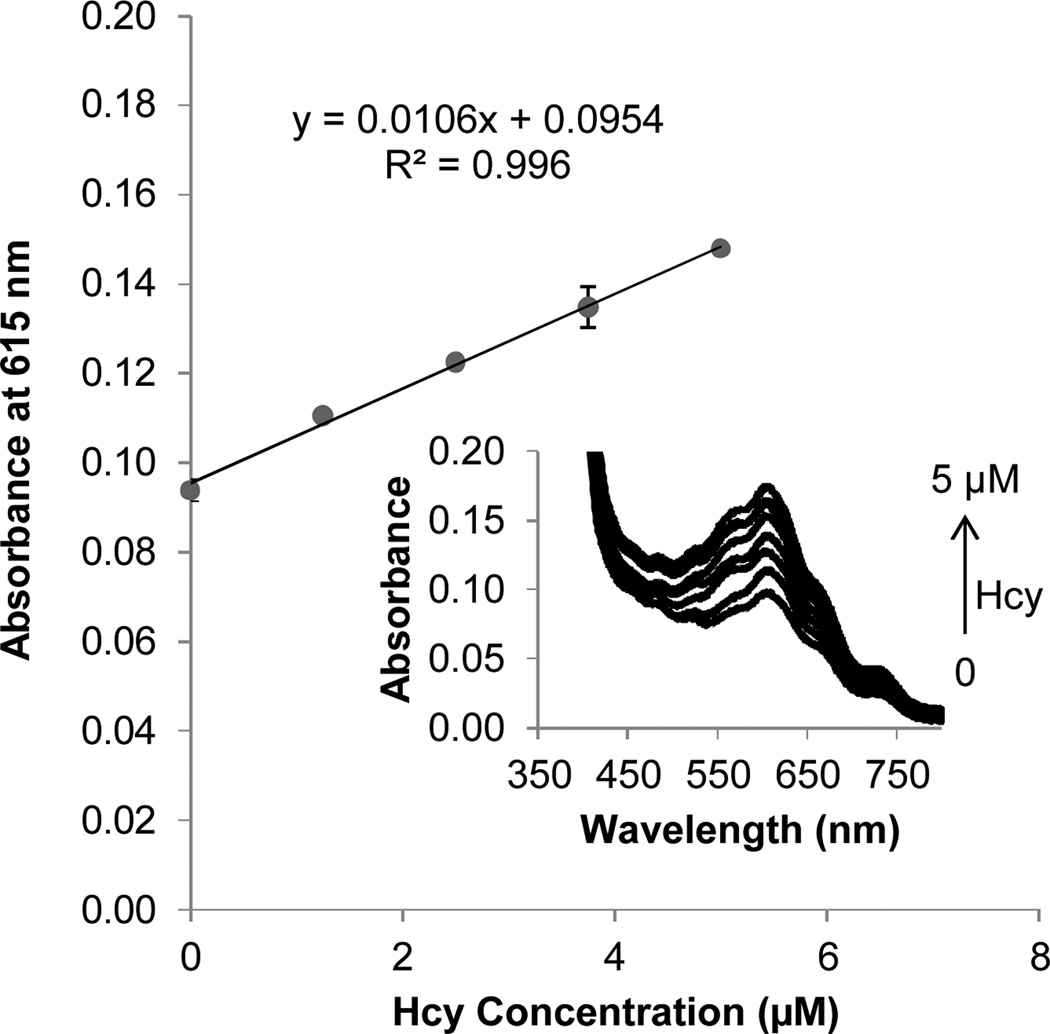

The spectral responses of BV2+ to Hcy concentration changes, in spiked reduced human plasma monitored at 615 nm, increased linearly with increasing Hcy concentration over a physiologically relevant concentration range (Fig. 4). The inset shows the respective spectral data. To test the limits of possible Cys and GSH interference with the assay, further experiments were carried out with added excess amounts of Cys and GSH to reduced human plasma solutions. Cys and GSH were found to generate significant response only when their concentrations reach 400 µM (almost double the normal concentration in healthy individuals) and 100 µM (almost 20 times the normal plasma levels) respectively. At these concentrations, their absorbance response was equivalent to that of 5 µM Hcy (Fig. S3, ESI†).

Fig. 4.

Spectral response of BV2+ towards increasing levels of spiked Hcy in reduced human plasma upon irradiation. Absorption spectra of solutions of BV2+ (20 mM) in 25% human blood plasma and 0.5 M Tris buffer (pH 7.0) spiked with 0–5 µM Hcy. Plasma (25% v/v) was added to an argon-saturated solution of viologen, thiol and buffer, and irradiated for 15 min using a Reptisun™ lamp.

To further evaluate the selectivity of the BV2+ towards Hcy, control experiments using series of other amino acids were performed. Other amino acids produced no significant absorption response as compared to Hcy, further demonstrating that BV2+ is Hcy specific (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Spectral response of BV2+ towards various spiked amino acids in human plasma upon irradiation. Absorption spectra of solutions of BV2+ (20 mM) in human blood plasma and 0.5 M Tris buffer (pH 7.0) spiked with 1.5 µM Hcy (dashed line) and 500 µM amino acids (solid lines = L-Ala, Arg, Gln, Met, Ser, Thr & Phe). Plasma (10% v/v) was added to an argon-saturated solution of viologen, amino acids and buffer and irradiated for 15 min using a Reptisun™ lamp.

In conclusion, we have developed a new, relatively simple and inexpensive assay for the selective detection of total Hcy directly in human blood plasma. This method has potential practical application in home test kits or point of care diagnostics because it involves the use of a less toxic chromogen, an inexpensive commercial light source, and simple sample processing, involving only reduction and filtration prior to photolysis and UV-vis monitoring.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 EB002044) and Boulder Diagnostics.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Detailed experimental procedures and additional absorption spectra data. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Werder SF. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2010;6:159–195. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s6564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glushchenko AV, Jacobsen DW. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007;9:1883–1898. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaluzna-Czaplinska J, Zurawicz E, Michalska M, Rynkowski J. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2013;60:137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marti-Carvajal AJ, Sola I, Lathyris D, Salanti G. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006612.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smulders YM, Blom HJ. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011;34:93–99. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9151-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton LAA, Sandhu K, Livingstone C, Leslie R, Davis J. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2010;10:489–500. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nekrassova O, Lawrence NS, Compton RG. Talanta. 2003;60:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(03)00173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng H, Chen W, Cheng Y, Hakuna L, Strongin R, Wang B. Sensors. 2012;12:15907–15946. doi: 10.3390/s121115907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung HS, Chen XQ, Kim JS, Yoon J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:6019–6031. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60024f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen DW, Gatautis VJ, Green R, Robinson K, Savon SR, Secic M, Ji J, Otto JM, Taylor LM. Clin. Chem. 1994;40:873–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu C, Zeng F, Luo M, Wu S. Nanotechnology. 2012;23 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/23/30/305503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang WH, Escobedo JO, Lawrence CM, Strongin RM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3400–3401. doi: 10.1021/ja0318838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao R, Lind J, Merenyi G, Eriksen TE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:12010–12015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang WH, Rusin O, Xu XY, Kim KK, Escobedo JO, Fakayode SO, Fletcher KA, Lowry M, Schowalter CM, Lawrence CM, Fronczek FR, Warner IM, Strongin RM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15949–15958. doi: 10.1021/ja054962n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escobedo JO, Wang W, Strongin RM. Nat. Protocols. 2006;1:2759–2762. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson C, Jr, Gutowsky H. J. Chem. Phys. 1963;39:58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nauser T, Koppenol WH, Schöneich C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:5329–5341. doi: 10.1021/jp210954v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang D, Crowe WE, Strongin RM, Sibrian-Vazquez M. Chem. Commun. 2009:1876–1878. doi: 10.1039/b819746f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.