Abstract

Intravenous lipid emulsions (LEs) are effective in the treatment of toxicity associated with various drugs such as local anesthetics and other lipid soluble agents. The goals of this study were to examine the effect of LE on left ventricular hemodynamic variables and systemic blood pressure in an in vivo rat model, and to determine the associated cellular mechanism with a particular focus on nitric oxide. Two LEs (Intralipid® 20% and Lipofundin® MCT/LCT 20%) or normal saline were administered intravenously in an in vivo rat model following induction of anesthesia by intramuscular injection of tiletamine/zolazepam and xylazine. Left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), blood pressure, heart rate, maximum rate of intraventricular pressure increase, and maximum rate of intraventricular pressure decrease were measured before and after intravenous administration of various doses of LEs or normal saline to an in vivo rat with or without pretreatment with the non-specific nitric oxide synthase inhibitor Nω-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME). Administration of Intralipid® (3 and 10 ml/kg) increased LVSP and decreased heart rate. Pretreatment with L-NAME (10 mg/kg) increased LSVP and decreased heart rate, whereas subsequent treatment with Intralipid® did not significantly alter LVSP. Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) increased mean blood pressure and decreased heart rate. The increase in LVSP induced by Lipofundin® MCT/LCT was greater than that induced by Intralipid®. Intralipid® (1%) did not significantly alter nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside-induced relaxation in endothelium-denuded rat aorta. Taken together, systemic blockage of nitric oxide synthase by L-NAME increases LVSP, which is not augmented further by intralipid®.

Keywords: lipid emulsion, left ventricular systolic pressure, blood pressure, nitric oxide, L-NAME.

Introduction

Lipid emulsions (LEs) have been used for the treatment of local anesthetic systemic toxicity 1,2,3. In addition, LEs are also effective in the treatment of toxicity associated with psychotropic drugs, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, parasiticides, or herbs 1,2. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity is a rare but potentially fatal complication that is intractable to conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation 3. Intravenous infusion of LE is effective in the treatment of cardiovascular collapse induced by a toxic dose of local anesthetics in animals and human patients 1,4-10. Intralipid® 20% (Fresenius Kabi AB, Uppsala, Sweden) with triglyceride, which contains 100% long-chain fatty acids, is most commonly used to treat local anesthetic systemic toxicity, although Lipofundin® MCT/LCT 20% (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany), with triglyceride, which contains 50% long-chain fatty acid and 50% medium-chain fatty acid, is sometimes used 4-6,9,10.

In in vitro studies, LE reverses vasodilation induced by a toxic dose of levobupivacaine in isolated rat aorta in part through decreased nitric oxide bioavailability 11,12. Intralipid® emulsion attenuates endothelium-dependent nitric oxide-mediated relaxation in isolated vessels and induces endothelial dysfunction 13,14. In in vivo and ex vivo studies, intravenous infusion of Intralipid® 20% or Lipofundin® MCT/LCT 20% increases blood pressure or systemic vascular resistance 15-18. In addition, shear stress exerted on the endothelium by blood flow in an in vivo state induces endothelial nitric oxide release 19. However, the effects of LE on left ventricular hemodynamic variables including left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), heart rate, maximum rate of intraventricular pressure increase (+dP/dtmax), and maximum rate of intraventricular pressure decrease (-dP/dtmax) in an in vivo rat model and the associated cellular mechanisms remain unknown. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to investigate the effect of intravenous infusion of two LEs (Intralipid® or Lipofundin® MCT/LCT) on left ventricular hemodynamic variables and systemic blood pressure in an in vivo rat model. The second aim was to elucidate the mechanism responsible for LE-induced changes in left ventricular hemodynamic variables, focusing particularly on nitric oxide. Based on previous reports, we tested the hypothesis that intravenous administration of Intralipid® would increase LVSP primarily by inhibition of nitric oxide 13-19.

Materials and Methods

Animal preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (KOATECH, Pyeongtaek, South Korea) were used in this study. All animals were maintained in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health in 1996. The protocol was approved by the Animal Research Committee at Gyeongsang National University. Animal preparation and surgery were performed as described previously 20. Briefly, animals received general anesthesia with an intramuscular injection of 15 mg/kg tiletamine/zolazepam (Zoletil50®; Virbac Lab., Carros, France) and 9 mg/kg xylazine (Rompun®; Bayer, Seoul, South Korea). If the tail moved (a sign of awakening) during the operation, an additional 5 mg/kg tiletamine/zolazepam and 3 mg/kg xylazine were injected to maintain an adequate level of anesthesia. Body temperature was monitored with a rectal thermometer (Sirecust 1260; Siemens Medical Electronics, MA, USA) and was maintained at 36-38°C using an electrical heating pad.

Experimental preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200-250 g were used for this set of experiments. For insertion of the catheter, the right carotid artery was exposed under anesthesia. Next, a 2-F Millar Catheter (Model SPR-407; Millar Instruments, Inc., Houston, TX, USA) was inserted into the left ventricle through the exposed right carotid artery for measurement of left ventricular hemodynamic variables or into the right carotid artery for measurement of systemic blood pressure under spontaneous respiration. The advancement of the catheter from the right carotid artery to the left ventricle was verified by a decrease in diastolic blood pressure. A pressure transducer (Model ML 118; AD Instruments Pty Ltd., Bella Vista, Australia) was connected to a digital analysis system to measure left ventricular hemodynamic variables or blood pressure (mean, systolic, and diastolic). Left ventricular hemodynamic variables and blood pressure were measured after stabilization for 10 min. LVSP, blood pressure, +dP/dtmax, -dP/dtmax, and heart rate were measured using a computer analysis program (ChartTM5 Pro; AD Instruments Pty Ltd.) as described previously 21. After insertion of the Millar Catheter, a 24-G catheter treated with heparin was inserted into the left femoral vein for drug infusion. Each experimental group was injected through the catheter with drugs according to the protocols below.

Experimental protocols

First, we measured the left ventricular hemodynamic effect of various doses of Intralipid® 20% that was infused into the left femoral vein of an in vivo rat model over 15-20 seconds using an infusion pump (Model AS50, Infusion pump; Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, IL, USA). The rats were randomly assigned to different groups to elucidate the dose-dependent effect of Intralipid® as follows: (1) Control group — 0.9% normal saline (3 or 10 ml/kg) was administered intravenously; (2) Intralipid® (1.5 ml/kg) group — Intralipid® 20% (1.5 ml/kg) was administered intravenously; (3) Intralipid® (3 ml/kg) group — Intralipid® 20% (3 ml/kg) was administered intravenously; and (4) Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) group—Intralipid® 20% (10 ml/kg) was administered intravenously. Left ventricular hemodynamic variables including the LVSP, +dP/dtmax, -dP/dtmax, and heart rate were recorded serially, and the baseline and maximum responses were assessed before and after infusion of various doses of Intralipid® 20% or normal saline, respectively.

Second, we measured the cumulative dose-left ventricular hemodynamic response for normal saline, Intralipid® 20%, and Lipofundin® MCT/LCT 20% at doses of 0.3, 1, 3, and 10 ml/kg to elucidate component-related effects of LEs. Subsequent doses were intravenously administered into the left femoral vein over approximately 5 seconds after the previous dose achieved maximum LVSP. The rats were randomly assigned to the following three groups to generate cumulative dose-response curves: (1) Control group — 0.9% normal saline was administered intravenously (n = 6); (2) Intralipid® group — Intralipid® 20% was administered intravenously (n = 6); and (3) Lipofundin® MCT/LCT group — Lipofundin® MCT/LCT 20% was administered intravenously (n = 6). Left ventricular hemodynamic variables were recorded serially to generate cumulative dose-response curves and were compared between groups to identify the component-related effects of LE.

Third, we measured cumulative dose-response curves by intravenous administration of the non-selective nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor Nω-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at doses of 0.001 to 30 mg/kg and identified the dosage of L-NAME at which maximal LVSP was induced (n = 8). In a preliminary experiment to determine the dose of L-NAME that produced maximal LVSP, cumulatively increasing doses of L-NAME were infused into the left femoral vein over approximately 5 seconds after the previous dose of L-NAME had elicited sustained LVSP. After infusion of 10 mg/kg L-NAME, the dose that produced maximal LVSP in a preliminary experiment (i.e., into the left femoral vein over approximately 5 seconds) produced a sustained left ventricular hemodymanic response, Intralipid® 20% (3 or 10 ml/kg) was administered into the left femoral vein over 15-20 seconds using an infusion pump to determine the left ventricular hemodynamic response, and left ventricular hemodynamic variables were continuously measured to generate L-NAME (10 mg/kg) and Intralipid® (3 or 10 ml/kg) dose-response curves.

Finally, we investigated the effect of Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) and normal saline (10 ml/kg) on the systemic blood pressure (mean, systolic, and diastolic) and heart rate in an in vivo rat model. Intralipid® or normal saline was infused into the left femoral vein over 15-20 seconds using an infusion pump. Mean, systolic, and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate were measured through the Millar catheter inserted into the right carotid artery, and baseline and maximum responses were assessed before and after infusion of Intralipid® 20% or normal saline, respectively.

Isometric tension measurement

Preparation of aortic rings from male Sprague Dawley rats weighing 250-300 g for tension measurement was performed as described in previous studies 11, 12. The effect of Intralipid® on relaxation induced by the nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside (Sigma Aldrich) in endothelium-denuded rat aorta was assessed. Intralipid® (1%) was added directly to the organ bath 20 min before phenylephrine (10-7 M)-induced precontraction in endothelium-denuded aorta. When the phenylephrine-induced contraction was stabilized, sodium nitroprusside was incrementally added to the organ bath to give concentrations of 10-10 to 10-7 M. Sodium nitroprusside concentration-response curves in endothelium-denuded rat aorta with or without Intralipid® (1%) were generated.

Data analysis

All values are shown as means ± standard deviation (SD). All hemodynamic variables are expressed as percentage of baseline hemodynamic variables before administration of LE, normal saline, or L-NAME. n indicates the number of rats. All analyses were performed using the Prism 5.0 (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA).

We performed analysis of variance (ANOVA) when the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were satisfied. We used the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality and Bartlett's test for homogeneity of variance 22,23. The effect of Intralipid® (1.5 and 3 ml/kg) and normal saline on the +dP/dtmax and -dP/dtmax was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test 24. The effect of Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) and normal saline on left ventricular hemodynamic variables, systemic blood pressure (mean and diastolic) and heart rate was analyzed using unpaired Student's t-test. The effect of the two LEs or Intralipid® on cumulative LE dose-left ventricular hemodynamic response curves and sodium nitroprusside-induced relaxation was analyzed using two-way repeated measure ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test. The effect of L-NAME alone and L-NAME plus Intralipid® (3 or 10 ml/kg) on left ventricular hemodynamic variables was analyzed using repeated measure ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

Data for the effect of Intralipid® (1.5 and 3 ml/kg) and normal saline on the LVSP and heart rate, which did not pass a test of normality, were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test 25. Data for the effect of L-NAME alone and L-NAME plus Intralipid® (3 ml/kg) on the heart rate and +dP/dtmax under violation of normality assumption were analyzed using Friedman nonparametric repeated measure ANOVA followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test. Data for the effect of Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) on systolic blood pressure, which did not pass a test of normality, were analyzed using Mann-Whitney test. LVSP responses to each dose of L-NAME alone under violation of normality assumption were analyzed using Friedman nonparametric repeated measure ANOVA followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test. Statistical significance was considered to be a P value less than 0.05.

Results

Effect of various doses of Intralipid® on left ventricular hemodynamic variables in an in vivo rat model

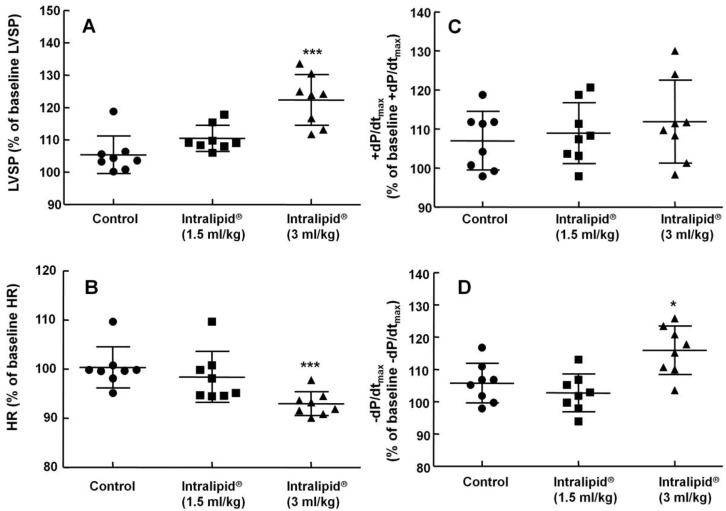

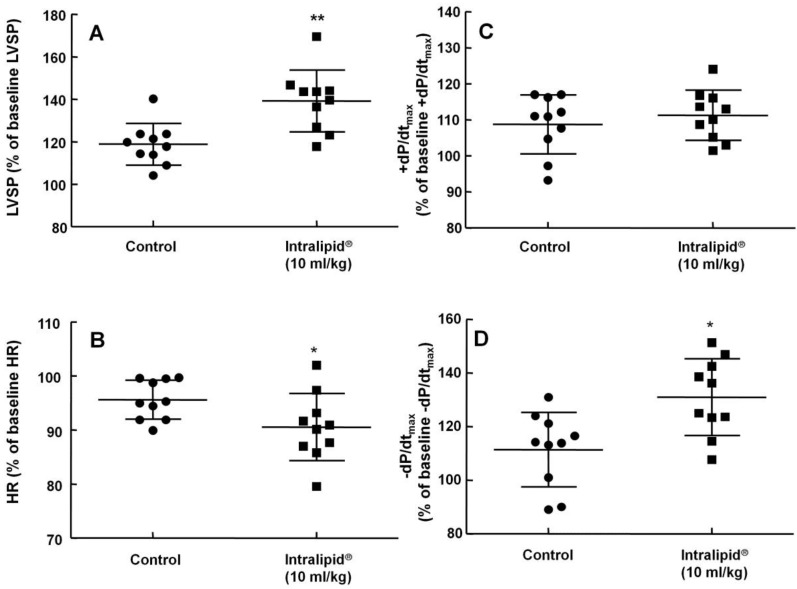

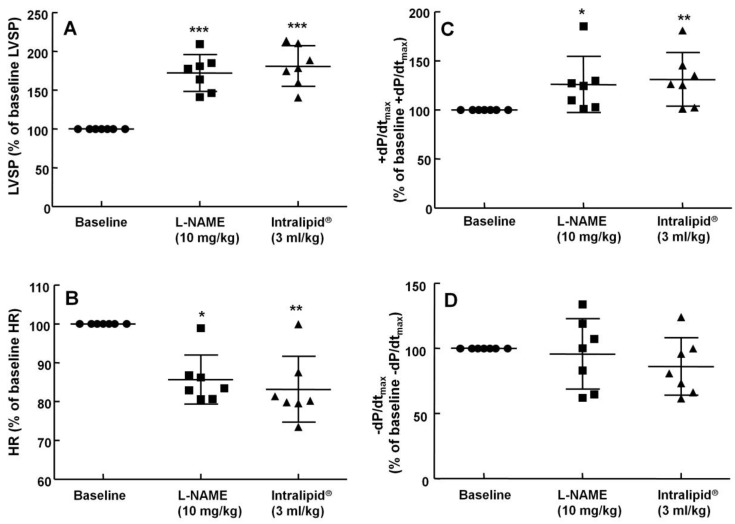

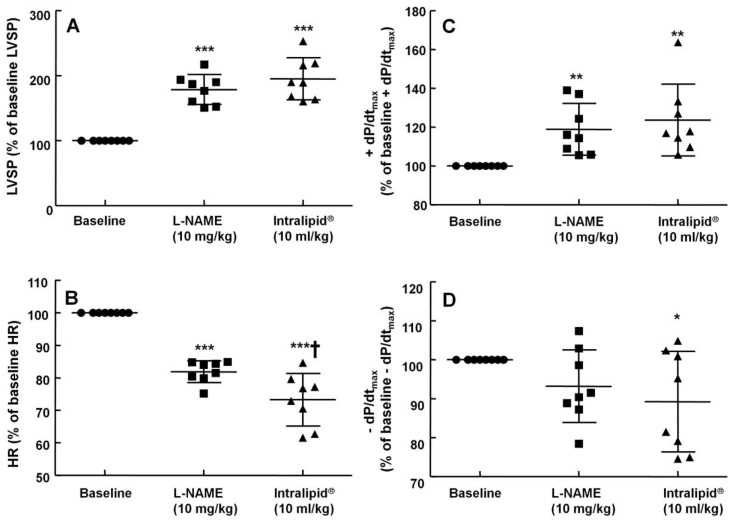

Baseline left ventricular hemodynamic variables were not significantly different among the groups (data not shown). Intralipid® (3 and 10 ml/kg) increased LVSP compared with control (P < 0.01, Fig. 1A and 2A), but decreased heart rate (P < 0.05 versus control, Fig. 1B and 2B). In addition, Intralipid® (3 and 10 ml/kg) significantly increased -dP/dtmax (P < 0.05 versus control, Fig. 1D and 2D).

Figure 1.

Effect of Intralipid® 20% (1.5 and 3 ml/kg) or normal saline on left ventricular hemodynamic variables including left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP, A), heart rate (HR, B), maximum rate of intraventricular pressure increase (+dP/dtmax, C), and maximum rate of intraventricular pressure decrease (-dP/dtmax, D) in an in vivo rat model. Control group: normal saline (3 ml/kg) was infused intravenously. Values are expressed as the percentage of baseline hemodynamic variables before administration of normal saline or Intralipid® and shown as means ± SD (n = 8/group). n indicates the number of rats. ***P < 0.001 and *P < 0.05 versus control.

Figure 2.

Effect of Intralipid® 20% (10 ml/kg) or normal saline on left ventricular hemodynamic variables including left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP, A), heart rate (HR, B), maximum rate of intraventricular pressure increase (+dP/dtmax, C), and maximum rate of intraventricular pressure decrease (-dP/dtmax, D) in an in vivo rat model. Control group: normal saline (10 ml/kg) was infused intravenously. Values are expressed as the percentage of baseline hemodynamic variables before administration of normal saline or Intralipid® and are shown as means ± SD (n = 10/group). n indicates the number of rats. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 versus control.

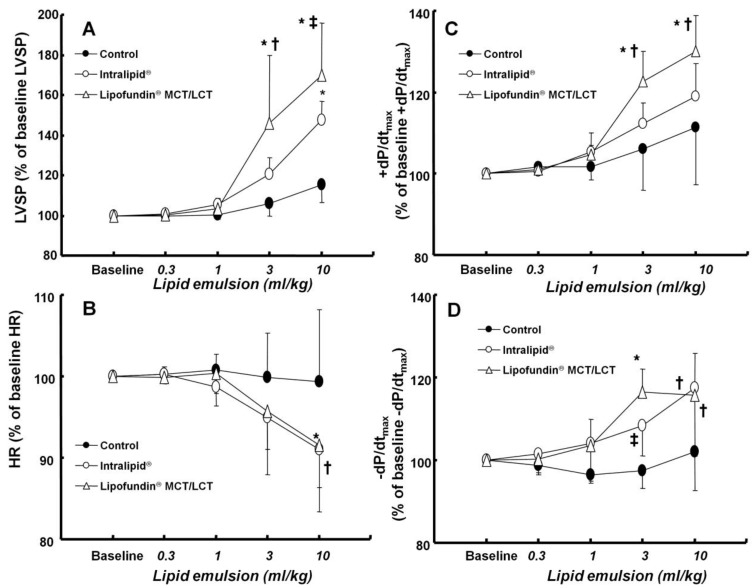

Effect of two lipid emulsions on the cumulative lipid emulsion-left ventricular hemodynamic response curves in an in vivo rat model

There was no significant difference in baseline left ventricular hemodynamic variables among the three groups (data not shown). Both Lipofundin MCT/LCT® (3 and 10 ml/kg) and Intralipid® (10 mg/kg) increased LVSP (P < 0.001 versus control, Fig. 3A). In particular, Lipofundin® MCT/LCT (3 and 10 ml/kg) produced higher LVSP than Intralipid® (P < 0.05 versus Intralipid®) (Fig. 3A). Lipofundin MCT/LCT® (10 ml/kg) and Intralipid® (10 mg/kg) decreased heart rate (P < 0.05 versus control, Fig. 3B). Lipofundin® MCT/LCT (3 and 10 ml/kg) increased +dP/dtmax (P < 0.001 versus control; P < 0.05 versus Intralipid®), whereas Intralipid® did not significantly affect +dP/dtmax (Fig. 3C). Lipofundin® MCT/LCT and Intralipid® (3 and 10 ml/kg) increased -dP/dtmax (P < 0.05 versus control, Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Effect of cumulative administration (0.3 to 10 ml/kg) of two lipid emulsions (Intralipid® 20% and Lipofundin® MCT/LCT [medium chain triglycerides/long-chain triglycerides] 20%) and normal saline on left ventricular hemodynamic variables, including left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP, A), heart rate (HR, B), maximum rate of intraventricular pressure increase (+dP/dtmax, C) and maximum rate of intraventricular pressure decrease (-dP/dtmax, D) in an in vivo rat model. Values are expressed as the percentage of baseline hemodynamic variables before the administration of normal saline or lipid emulsion and shown as means ± SD (n = 6/group). n indicates the number of rats. A: *P < 0.001 versus control. †P < 0.01 and ‡P < 0.05 versus Intralipid®. B: *P < 0.05 and †P < 0.01 versus control. C: *P < 0.001 versus control. †P < 0.05 versus Intralipid®. D: *P < 0.001, †P < 0.01, and ‡P < 0.05 versus control.

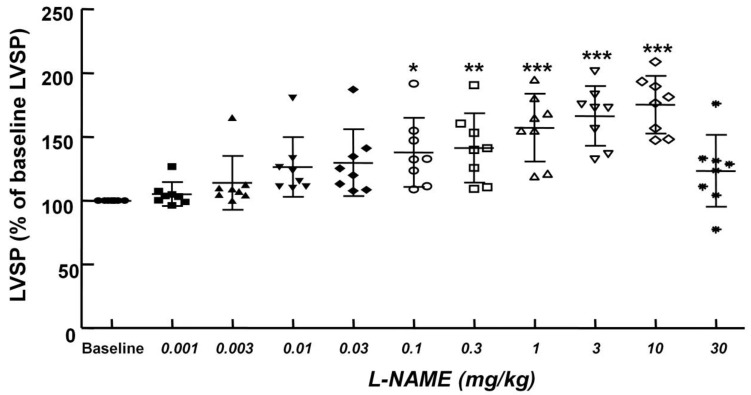

Effect of Intralipid® on left ventricular hemodynamic variables in an in vivo rat model after pretreatment with L-NAME

The non-specific NOS inhibitor L-NAME (0.1 to 10 mg/kg) increased LVSP in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.05 versus baseline, Fig. 4). The dose of L-NAME that induced maximal LVSP was approximately 10 mg/kg (Fig. 4). Pretreatment with L-NAME (10 mg/kg) increased LVSP (P < 0.001 versus baseline), whereas additional treatment with Intralipid® (3 and 10 ml/kg) did not significantly alter LVSP compared with L-NAME pretreatment alone (Fig. 5A and 6A). Similarly, L-NAME (10 mg/kg) alone decreased heart rate (P < 0.05 versus baseline), whereas subsequent addition of Intralipid® (3 ml/kg) did not significantly alter heart rate relative to the L-NAME-pretreated state (Fig. 5B). Subsequent addition of high-dose Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) attenuated heart rate compared with L-NAME alone (P < 0.01, Fig. 6B). L-NAME (10 mg/kg) alone increased +dP/dtmax (P < 0.05 versus baseline, Fig. 5C and 6C), whereas subsequent Intralipid® (3 and 10 ml/kg) did not significantly alter +dP/dtmax compared with the L-NAME-pretreated state (Fig. 5C and 6C). Neither L-NAME (10 mg/kg) alone nor combined treatment with L-NAME (10 mg/kg) and Intralipid® (3 ml/kg) significantly altered baseline -dP/dtmax compared with baseline (Fig. 5D and 6D). However, combined treatment with L-NAME (10 mg/kg) and high-dose Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) significantly decreased -dP/dtmax compared with baseline (P < 0.05, Fig. 6D).

Figure 4.

Cumulative Nω-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME) dose-left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP) response curves in an in vivo rat model. Values are expressed as the percentage of baseline LVSP before administration of L-NAME and are shown as mean ± SD (n = 8). n indicates the number of rats. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus baseline.

Figure 5.

The effects of subsequent administration of Intralipid® 20% (3 ml/kg) on hemodynamic variables including left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP, A), heart rate (HR, B), maximum rate of intraventricular pressure increase (+dP/dtmax, C) and maximum rate of intraventricular pressure decrease (-dP/dtmax, D) in an in vivo rat model pretreated with Nω-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME, 10 mg/kg), as described in Methods. Values are expressed as the percentage of baseline hemodynamic variable before the administration of L-NAME and are shown as means ± SD (n = 7/group). n indicates the number of rats. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05 compared with baseline.

Figure 6.

The effects of administration of Intralipid® 20% (10 ml/kg) on hemodynamic variables including left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP, A), heart rate (HR, B), maximum rate of intraventricular pressure increase (+dP/dtmax, C), and maximum rate of intraventricular pressure decrease (-dP/dtmax, D) in an in vivo rat model after pretreatment with Nω-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME, 10 mg/kg), as described in Methods. Values are expressed as the percentage of baseline hemodynamic variable before the administration of L-NAME and are shown as means ± SD (n = 8/group). n indicates the number of rats. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05 compared with baseline. †P < 0.01 compared with L-NAME (10 mg/kg) alone.

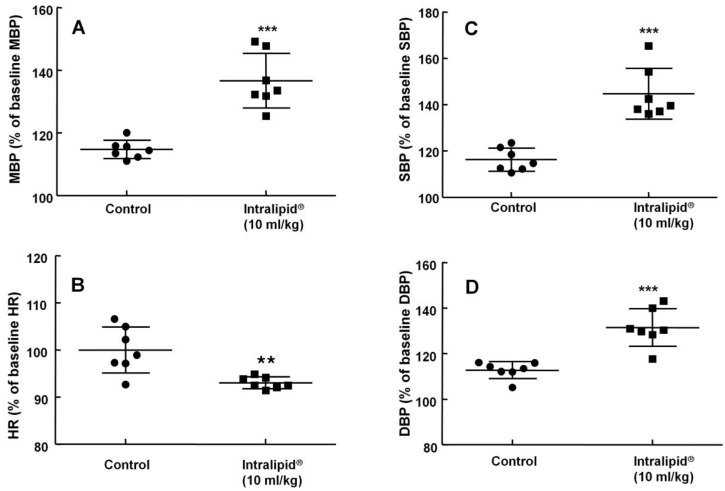

Effect of Intralipid® on blood pressure and heart rate in an in vivo rat model

Baseline blood pressure and heart rate were not significantly different between the two groups (Intralipid® at 10 ml/kg and control groups) (data not shown). Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) increased mean, systolic, and diastolic blood pressure (P < 0.001 versus control, Fig. 7A, C, and D) and decreased heart rate (P < 0.01 versus control, Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Effect of Intralipid® 20% (10 ml/kg) or normal saline on mean blood pressure (MBP, A), heart rate (HR, B), systolic blood pressure (SBP, C), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP, D) in an in vivo rat model. Control group: normal saline (10 ml/kg) was infused intravenously. Values are expressed as the percentage of baseline hemodynamic variables before administration of normal saline or Intralipid® and are shown as means ± SD (n = 7/group). n indicates the number of rats. ***P < 0.001 and **P < 0.01 versus control.

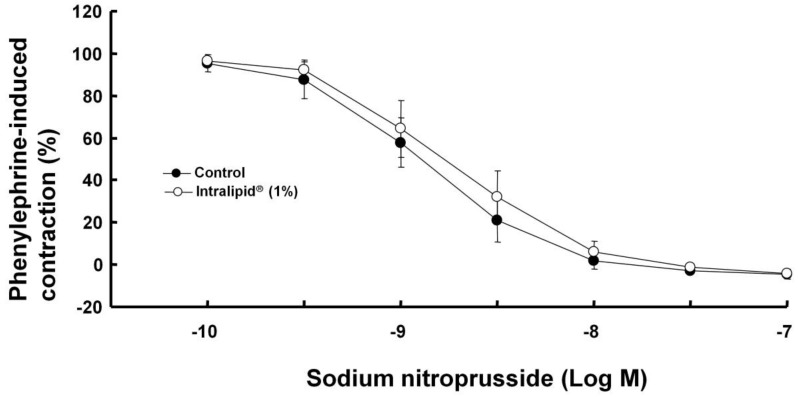

Effect of Intralipid® on sodium nitroprusside-induced relaxation in isolated endothelium-denuded rat aorta

Intralipid® (1%) did not significantly alter sodium nitroprusside-induced relaxation in endothelium-denuded rat aorta (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Effect of Intralipid® (1%) on sodium nitroprusside-induced relaxation in isolated endothelium-denuded rat aorta. Values are expressed as the percentage relaxation of precontraction induced by phenylephrine (10-7 M) and are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6/group). n indicates the number of rats.

Discussion

This is the first study suggesting that systemic blockage of NOS by L-NAME increases LVSP in an in vivo rat model, which is not augmented further by intralipid®. The major findings of the current study are as follows: 1) Intralipid® (3 and 10 ml/kg) increased the LVSP; 2) Intralipid® (3 and 10 ml/kg) administered after L-NAME pretreatment did not significantly alter LVSP in vivo compared with L-NAME pretreatment alone; 3) Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) increased mean blood pressure; 4) Lipofundin® MCT/LCT increased LVSP to a greater extent than Intralipid®; and 5) Both LEs (3 and 10 ml/kg) produced an increased -dP/dtmax.

Although an early report demonstrated that long-chain triglycerides have virtually no effect on hemodynamics, it was recently reported that LEs including Intralipid® and Lipofundin® MCT/LCT increase arterial blood pressure and systemic vascular resistance in an in vivo or ex vivo state 15-18, 26. Similar to previous reports, Intralipid® increased the mean blood pressure and LVSP in our study 15, 16, 18. Although LVSP is affected not only by preload but also by myocardial contractility and afterload, Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) increased LVSP and mean blood pressure, whereas pretreatment with the non-specific NOS inhibitor L-NAME almost completely abolished the Intralipid®-induced LVSP increase. Thus, the increased LVSP and mean blood pressure evoked by Intralipid® in the current study seems to be due to the Intralipid®-induced increase in systemic vascular resistance observed in a previous study 15. In the study by Van de Velde et al, emulsions of only long-chain triglycerides were shown to have virtually no effect on hemodynamics, whereas a mixture of medium-chain triglycerides/long-chain triglycerides increased the mean aortic blood pressure 17. However, Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) containing triglyceride with only long-chain fatty acids increased LVSP and mean blood pressure in the current study. This difference may be due to differences in the speed of intravenous infusion (15-20 second versus 30 min), dosage, or species (rat versus dog).

Intralipid® attenuates endothelium-dependent nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation and post-ischemic vasodilation through decreased nitric oxide bioavailability 13,14. In addition, in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, Lipofundin® MCT/LCT and Intralipid® increase production of oxidized dichlorofluorescein, which is considered an indicator of reactive oxygen species 11. Acute administration of the non-specific NOS inhibitor L-NAME causes hypertension and increased vascular resistance through inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide release 27-29. Taken together with findings of previous studies, the inability of Intralipid® to induce an increase in LVSP after L-NAME pretreatment (Fig. 5A and 6A) appears to be associated with Intralipid®-mediated nitric oxide inhibition 27-29. This Intralipid®-mediated nitric oxide inhibition seems to be one of the putative underlying mechanisms responsible for Intralipid®-induced LSVP increase and may contribute to the increased systemic vascular resistance, decreased flow-mediated nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation, and decreased arterial compliance observed during intravenous infusion of Intralipid® in previous in vivo studies 15,16. Consistent with a previous report, Intralipid® (1%) did not significantly alter endothelium-independent relaxation induced by the nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside in endothelium-denuded aorta (Fig. 8), therefore the Intralipid®-induced increase in LVSP may be associated with inhibition of nitric oxide production rather than inhibition of nitric oxide transfer from endothelium to vascular smooth muscle 13. However, as L-NAME is a non-specific NOS inhibitor, further studies of the effect of neuronal and inducible NOS inhibitors on the LE-mediated LVSP increase in an in vivo model are needed to clarify which subtype of NOS is mainly involved in the inhibition of nitric oxide induced by LE. Further studies of the effect of LE on endothelial NOS phosphorylation in the small resistance arteries that are predominantly involved in regulation of blood pressure are also needed. In addition, the type of fatty acid present in LE that is primarily involved in the LE-mediated increase in LVSP in an in vivo state remains to be determined. As LE appears to attenuate nitric oxide release in an in vivo state, the magnitude of the LE-mediated LVSP and blood pressure increase may be attenuated in patients with compromised endothelial function, such as those with diabetes or hypertension. Acute administration of L-NAME alone increased blood pressure and decreased heart rate in this and previous studies 27,29. Intralipid® (3 or 10 ml/kg) alone increased LVSP and decreased heart rate (Fig. 1A, 1B, 2A and 2B), but did not significantly alter LVSP and heart rate in the L-NAME-pretreated in vivo state (Fig. 5A, 5B, and 6A). High-dose Intralipid® (10 ml/kg) attenuated heart rate compared with L-NAME alone (Fig. 6B). In addition, Intralipid® increased mean blood pressure and decreased heart rate (Fig. 7A and B). Therefore, the Intralipid®-induced decrease in heart rate (Fig. 7B) may be partially associated with a reflex response to the increase in LVSP and blood pressure (Fig. 2A and 7A) that appears to be caused by increased total vascular resistance. In contrast, an increase in free fatty acids decreases baroreflex sensitivity in humans 30. This discrepancy may be ascribed to differences in the experimental method, state of consciousness (anesthetized versus not anesthetized), or species (rat versus human) 30.

Both LEs (3 and 10 ml/kg) increased -dP/dtmax, which can be regarded as an indicator of diastolic function of the left ventricle. In addition, Lipofundin® MCT/LCT (3 and 10 ml/kg) increased +dP/dtmax whereas Intralipid® did not have a significant effect. As ±dP/dtmax is affected by afterload as well as myocardial contractility itself in an in vivo state, it is very difficult to distinguish whether the change in ±dP/dtmax is due to increased contractility or increased afterload evoked by LE. Therefore, further study into the effect of Lipofundin® MCT/LCT and Intralipid® on myocardial contractility using an isolated ex vivo rat heart model is needed to determine which LE has the more positive inotropic effect.

The mechanism of action of LEs in the treatment of local anesthetic-induced cardiac toxicity is not completely understood. The “lipid sink” theory (reduced tissue binding because of a re-established equilibrium in the plasma lipid phase) and “energetic-metabolic effect” (reversal of the inhibition of mitochondrial fatty acid transport) are the most widely known theories 7, 8, 12, 31, 32. Local anesthetic (levobupivacaine, mepivacaine, and ropivacaine)-induced dose-dependent vascular responses in isolated aorta, including vasoconstriction at lower doses and vasodilation at higher doses, are enhanced by the non-specific NOS inhibitor L-NAME, suggesting that vasodilation induced by a toxic dose of local anesthetics involves nitric oxide release 11,33-36. Levobupivaciane, ropivacaine, and mepivacaine induce endothelial NOS phosphorylation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells and rat aorta 11,12,34,36. In particular, ropivacaine-induced contraction is enhanced by the non-specific NOS inhibitor L-NAME in endothelium-intact aorta, whereas ropivacaine-induced contraction is not significantly affected by the neuronal NOS inhibitor Nω-propyl-L-arginine hydrochloride or the inducible NOS inhibitor 1400W dihydrochloride, suggesting that ropivacaine-induced contraction is attenuated by endothelial NOS 36. Local anesthetic toxicity produces myocardial depression and cardiac arrest 37. Taken together with previous reports, results of the current study implicate inhibition of nitric oxide release as a mechanism by which LE may partially contribute to the reversal of vascular collapse due to severe vasodilation induced by toxic dose of local anesthetics 3,11,12,33-37. This might be considered a direct mechanism, compared with the well-known indirect lipid sink theory. Intralipid® infusion may produce increased blood pressure in patients with normal endothelial integrity. Therefore, blood pressure changes in patients taking intravenous infusion of Intralipid® should be carefully monitored. Taking into consideration only the direct effect of LE, because the Lipofundin® MCT/LCT-induced LVSP increase was higher than that induced by Intralipid® in the current study, Lipofundin® MCT/LCT seems to be the more favorable LE in terms of recovery of vascular tone after vascular collapse induced by toxic dose of local anesthetics in an in vivo state.

Our study had several limitations. Our results suggest that the increase in LVSP induced by Intralipid® may be mainly associated with inhibition of nitric oxide. However, LEs did not induce vasoconstriction in isolated endothelium-intact rat aorta in our previous in vitro study 12. These discrepant results may be ascribed to the following factors: 1) the vascular endothelium in an in vivo model is exposed to blood flow, possibly leading to more shear stress-induced nitric oxide release than the basal NO release of isolated blood vessels in the in vitro model; 2) small resistance arterioles with a diameter less than 300 μm, such as those associated with the rat mesenteric artery, are primarily involved in the regulation of organ blood flow and are the main determinants of blood pressure, whereas our previous in vitro study involved isolated rat aorta which is a conduit vessel; and 3) the near abolishment of Intralipid®-induced LVSP increase by L-NAME pretreatment may be associated with non-specific inhibition of all subtypes of NOS rather than specific inhibition of endothelial NOS 19,38.

In conclusion, taken together our results suggest that systemic inhibition of NOS by L-NAME enhances LVSP in an in vivo state, which is not augmented further by intralipid®.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (KRF-2012-1035). This work was also supported by clinical research fund (GNUHCRF-2012-012) from the Gyeongsang National University Hospital.

References

- 1.Cave G, Harvey M, Graudins A. Intravenous lipid emulsion as antidote: a summary of published human experience. Emerg Med Australas. 2011;23:123–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothschild L, Bern S, Oswald S. et al. Intravenous lipid emulsion in clinical toxicology. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:51. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-18-51. (available at: http://www.sjtrem.com/content/18/1/51. Accessed August 13, 2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinberg GL. Lipid emulsion infusion. Resuscitation for local anesthetic and other drug overdose. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:180–187. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825ad8de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dix SK, Rosner GF, Nayar M. et al. Intractable cardiac arrest due to lidocaine toxicity successfully resuscitated with lipid emulsion. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:872–874. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318208eddf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foxall G, McCahon R, Lamb J. et al. Levobupivacaine-induced seizures and cardiovascular collapse treated with Intralipid. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:516–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zausig YA, Zink W, Keil M. et al. Lipid emulsion improves recovery from bupivacaine-induced cardiac arrest, but not from ropivacaine- or mepivacaine-induced cardiac arrest. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1323–1326. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181af7fb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg G. Lipid rescue resuscitation from local anaesthetic cardiac toxicity. Toxicol Rev. 2006;25:139–145. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200625030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozcan MS, Weinberg G. Update on the use of lipid emulsions in local anesthetic systemic toxicity: a focus on differential efficacy and lipid emulsion as part of advanced cardiac life support. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2011;49:91–103. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318217fe6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren JA, Thoma RB, Georgescu A. et al. Intravenous lipid infusion in the successful resuscitation of local anesthetic-induced cardiovascular collapse after supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1578–1580. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000281434.80883.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charbonneau H, Marcou TA, Mazoit JX. et al. Early use of lipid emulsion to treat incipient mepivacaine intoxication. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:277–278. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31819340be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ok SH, Park CS, Kim HJ. et al. Effect of two lipid emulsions on reversing high-dose levobupivacaine-induced reduced vasoconstriction in the rat aortas. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2013;13:370–380. doi: 10.1007/s12012-013-9218-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ok SH, Sohn JT, Baik JS. et al. Lipid emulsion reverses levobupivacaine-induced responses in isolated rat aortic vessels. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:293–301. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182054d22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundman P, Tornvall P, Nilsson L. et al. A triglyceride-rich fat emulsion and free fatty acids but not very low density lipoproteins impair endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Atheroslcerosis. 2001;159:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osanai H, Okumura K, Hayakawa M. et al. Ascorbic acid improves postischemic vasodilatation impaired by infusion of soybean oil into canine iliac artery. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36:687–692. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200012000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stojiljkovic MP, Zhang D, Lopes HF. et al. Hemodynamic effects of lipids in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1674–R1679. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.6.R1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Robalino G. et al. Intravenous intralipid-induced blood pressure elevation and endothelial dysfunction in obese African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:609–614. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van de Velde M, Wouters PF, Rolf N. et al. Comparative hemodynamic effects of three different parenterally administered lipid emulsions in conscious dogs. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:132–137. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199801000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fettiplace M, Ripper R, Lis K. et al. Rapid cardiotonic effects of lipid emulsion infusion. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(e):156–162. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318287f874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu D, Kassab GS. Role of shear stress and stretch in vascular mechanobiology. J R Soc Interface. 2011;8:1379–1385. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang IS, Park MY, Shin IW. et al. Ethyl pyruvate has anti-inflammatory and delayed myocardial protective effects after regional ischemia/reperfusion injury. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51:838–844. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.6.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin IW, Jang IS, Lee SM. et al. Myocardial protective effect by ulinastatin via an anti-inflammatory response after regional ischemia/reperfusion injury in an in vivo rat heart model. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;61:499–505. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2011.61.6.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples) Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. Iowa, USA: Iowa State University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yosef H, Ajit CT. Multiple comparison procedures. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conover WJ. Practical nonparametric statistics. New York, USA: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mjos OD. Effect of free fatty acids on myocardial function and oxygen consumption in intact dogs. J Clin Invest. 1971;50:1386–1389. doi: 10.1172/JCI106621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.La Fountaine MF, Radulovic M, Cardozo CP. et al. Effects of acute nitric oxide synthase inhibition on lower leg vascular function in chronic tetraplegia. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:538–544. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11754555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sander M, Chavoshan B, Victor RG. A large blood pressure-raising effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibition in humans. Hypertension. 1999;33:937–942. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.4.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu CT, Chang KC, Wu CY. et al. Acute effects of nitric oxide blockade with L-NAME on arterial haemodynamics in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:1237–1243. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gadegbeku CA, Dhandayuthapani A, Sadler ZE. et al. Raising lipids acutely reduces baroreflex sensitivity. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:479–485. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(02)02275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ok SH, Han JY, Lee SH. et al. Lipid emulsion-mediated reversal of toxic-dose aminoamide local anesthetic-induced vasodilation in isolated rat aorta. Korea J Anesthesiol. 2013;64:353–359. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.64.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Partownavid P, Umar S, Li J. et al. Fatty-acid oxidation and calcium homeostasis are involved in the rescue of bupivacaine-induced cardiotoxicity by lipid emulsion in rats. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2431–2437. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182544f48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi YS, Jeong YS, Ok SH. et al. The direct effect of levobupivacaine in isolated rat aorta involves lipoxygenase pathway activation and endothelial nitric oxide release. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:341–349. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c76f52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sung HJ, Choi MJ, Ok SH. et al. Mepivacaine-induced contraction is attenuated by endothelial nitric oxide release in isolated rat aorta. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;90:863–872. doi: 10.1139/y2012-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baik JS, Sohn JT, Ok SH. et al. Levobupivacaine-induced contraction of isolated rat aorta is calcium dependent. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;89:467–476. doi: 10.1139/y11-046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ok SH, Han JY, Sung HJ. et al. Ropivacaine-induced contraction is attenuated by both endothelial nitric oxide and voltage-dependent potassium channels in isolated rat aortae. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:565271.. doi: 10.1155/2013/565271. doi: 10.1155/2013/565271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groban L. Central nervous system and cardiac effects from long-acting amide local anesthetic toxicity in the intact animal model. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:3–11. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2003.50014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christensen KL, Mulvany MJ. Location of resistance arteries. J Vasc Res. 2001;38:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000051024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]