Abstract

Immunogens based on the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) Envelope (Env) glycoprotein have to date failed to elicit potent and broadly neutralizing antibodies against diverse HIV-1 strains. An understudied area in the development of HIV-1 Env-based vaccines is the impact of various adjuvants on the stability of the Env immunogen and the magnitude of the induced humoral immune response. We hypothesize that optimal adjuvants for HIV-1 gp140 Env trimers will be those with high potency but also those that preserve structural integrity of the immunogen and those that have a straightforward path to clinical testing. In this report, we systematically evaluate the impact of 12 adjuvants on the stability and immunogenicity of a clade C (CZA97.012) HIV-1 gp140 trimer in guinea pigs and a subset in non-human primates. Oil-in-water emulsions (GLA-emulsion, Ribi, Emulsigen) resulted in partial aggregation and loss of structural integrity of the gp140 trimer. In contrast, alum (GLA-alum, Adju-Phos, Alhydrogel), TLR (GLA-aqueous, CpG, MPLA), ISCOM (Matrix M) and liposomal (GLA-liposomes, virosomes) adjuvants appeared to preserve structural integrity by size exclusion chromatography. However, multiple classes of adjuvants similarly augmented Env-specific binding and neutralizing antibody responses in guinea pigs and non-human primates.

Introduction

The development and evaluation of novel HIV-1 Env glycoprotein immunogens that can induce potent and broad neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against diverse HIV-1 strains is a critical priority of the HIV-1 vaccine field [1–3]. HIV-1 Env is the sole target of nAbs and consists of two non-covalently associated fragments: the receptor-binding fragment gp120 and the fusion fragment gp41. Three copies of each heterodimer constitute the mature, trimeric viral spike (gp120/gp41)3 which facilitates viral entry into target CD4 T-cells [4].

With the failure of monomeric gp120 immunogens to elicit broadly reactive nAbs in animal models [5, 6] and humans [7, 8], trimeric gp140 immunogens have been developed [9–12] and have shown improved nAb responses in several studies [9, 11, 13]. However, HIV-1 Env trimers typically require adjuvants to activate innate immunity and to optimize immunogenicity. Adjuvants can be classified into two general categories: improved delivery systems and immune potentiators [14–16]. Delivery-system adjuvants, whose mode of action have traditionally been thought to involve controlled release or a depot effect, although newer evidence suggests they may enhance immunogenicity by triggering inflammasome processes [17], include aluminum compounds, emulsions, liposomes, virosomes and immune stimulating complexes (ISCOMs). Immune potentiating adjuvants, on the other hand, rely on directly stimulating the innate immune system and include TLR ligands, saponins, cytokines, nucleic acids, bacterial products and lipids. Several adjuvants have been formulated to provide both delivery and immune potentiating components simultaneously [14–16]. We hypothesize that it will likely be important to maintain HIV-1 Env trimer structural integrity in any given adjuvant. We therefore sought to address the understudied question of the impact of various adjuvants on HIV-1 Env trimer immunogen stability, as well as their ability to augment the magnitude of binding and neutralizing antibodies. We observed that emulsion-based adjuvants led to Env trimer aggregation and dissociation, but that multiple classes of adjuvants augmented antibody responses to the Env trimer to a similar extent in guinea pigs and non-human primates.

Materials & Methods

Production of C97ZA.012 Clade C gp140 Env trimer

For protein production, a stable 293T cell line expressing biochemically stable, His-tagged CZA97.012 (clade C) gp140 trimer was generated by Codex Biosolutions as previously described [11]. The stable line was grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin and puromycin) to confluence and then changed to serum-free Freestyle 293 expression medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with the same antibiotics. The cell supernatant was harvested at 96–108 hours after medium change. His-tagged gp140 protein was purified by Ni-NTA (Qiagen) followed by gel-filtration chromatography as previously described [11, 12].

Adjuvants and Size-exclusion chromatography

Clade C gp140 trimer was evaluated for stability in aluminum-based [Adju-Phos, Alhydrogel, Glucopyranosyl Lipid Adjuvant (GLA)-alum], TLR-based (GLA-aqueous, CpG, MPLA), ISCOM-based (Matrix M), emulsion-based (GLA-emulsion, Ribi, Emulsigen) or liposome-based (virosome, GLA-liposome) adjuvants (Table 1). GLA adjuvants were kindly provided by the Infectious Disease Research Institute (IDRI) (Seattle, WA, USA), and virosomes were provided by Crucell (Leiden, the Netherlands). All other adjuvants were purchased commercially from Sigma (Ribi, MPLA), Isconova (Matrix M), Brenntag (AdjuPhos, Alhydorgel), MVP Laboratories (Emulsigen), and Midland Certified Reagent Company (CpG). Clade C gp140 trimer (100μg) was mixed with the various adjuvants according to each supplier’s instructions and incubated for 1-hour at 37°C. Protein was re-purified from the adjuvants by mini Ni-NTA columns (Pierce) and assessed by size exclusion chromatography on a Superose 6 column (GE Healthcare) in 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 150 mM NaCl.

Table 1. Summary of adjuvants used in study.

Descriptions of the adjuvants tested with HIV-1 clade C gp140 Env trimer and their mechanisms of action.

| Adjuvant Format | Adjuvant | Description | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum based | a Adju-Phos | Aluminum phosphate wet gel suspension | Depot effect, induction of inflammation, conversion of soluble antigen to particulate form for efficient APC phagocytosis [27] [28] |

| a Alhydrogel | Aluminum hydroxide wet gel suspension | Depot effect, induction of inflammation, conversion of soluble antigen to particulate form for efficient APC phagocytosis [27] [28] | |

| GLA-Alum | Aluminum formulation of synthetic glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant (GLA) | TLR4 agonist [29, 30] | |

| TLR Based | c GLA-Aqueous | Nanosuspension of GLA in an aqueous base | TLR4 agonist [30] |

| b CpG | Synthetic immunostimulatory di-nucleotide | TLR9 agonist [31] | |

| b MPLA | Low-toxicity derivative of the lipid A region of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | TLR4 agonist [32] | |

| ISCOM based | b Matrix M | Saponin-based cage-like nano-particles formulated with cholesterol and phospholipids | Mechanism undefined but induces strong T-helper 1 and 2 responses [33] |

| Emulsion based | c GLA-Emulsion | Oil-in-water formulation of GLA | TLR4 agonist [29, 30] |

| Ribi | Monophosphoryl lipid, synthetic trehalose dicorynomycolate in 2% oil (squalene)-Tween 80-water | TLR2/TLR4 agonist [34] | |

| Emulsigen | Stable mineral oil-in-water emulsion | Depot effect | |

| Liposomal based | a Virosome | Spherical vesicles with mixture of synthetic & natural phospholipids holding influenza hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins | HA and NA proteins provide properties which facilitate efficient vesicle uptake by and subsequent activation of cells of the immune system [26] |

| GLA Liposome | Liposomal formulation of GLA | TLR4 agonist [30] |

licensed adjuvants;

has undergone early phase clinical testing;

soon entering early phase clinical testing

Animals and immunizations

Outbred female Hartley guinea pigs (Elm Hill) (n=5/group) were housed at the Animal Research Facility of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center under approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocols. Guinea pigs were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with clade C gp140 trimer (100 μg/animal) in the presence or absence of the various adjuvants at weeks 0, 4, 8 in 500 μl injection volumes divided between the right and left quadriceps. Serum samples were obtained 4 weeks after each immunization by vena cava blood draws. For non-human primate studies, specific-pathogen-free rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were housed at the New England Primate Research Center (Southborough, MA) and Bioqual Incorporated (Rockville, MD) under approved IACUC protocols. Monkeys were immunized i.m with clade C gp140 trimer (250 μg/animal) in GLA aqueous, Matrix M or virosome adjuvants at weeks 0, 4, 8 (500 μl injection volume) divided equally between the two quadriceps muscles. Env trimers used in all animal immunizations were mixed immediately before immunizations and not subjected to the 1-hour, 37°C incubation used in stability assessments. Serum samples obtained 4 weeks after each immunization for both guinea pigs and non-human primates were analyzed in endpoint enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for binding antibody responses and peak immunogenicity samples (post-3rd vaccination) in TZM.bl neutralization assays.

ELISA binding antibody assay

Serum binding antibody titers against clade C gp140 trimer were determined by endpoint ELISAs as previously described [11, 12]. Briefly, 96-well Maxisorp ELISA plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific), coated over-night with 100 μl/well of 1 μg/ml clade C gp140, were blocked for 2.5 hours with PBS/Casein (Pierce). Guinea pig sera were then added in serial dilutions and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. The plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma) and incubated for 1 hour with a 1/2,000 dilution of a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG secondary antibody (Fisher Scientific) for NHP assays. The plates were washed three times and developed with SureBlue tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) microwell peroxidase (KPL Research Products), stopped by the addition of stop solution (KPL Research products), and analyzed at 450 nm/550 nm with a Spectramax Plus ELISA plate reader (Molecular Devices) using Softmax Pro 4.7.1 software. ELISA endpoint titers were defined as the highest reciprocal serum dilution that yielded an absorbance >2-fold over background values.

TZM.bl neutralization assay

Neutralizing antibody responses against tier 1 HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses were measured by using luciferase-based virus neutralization assays with TZM.bl cells as previously described [11, 12, 18] [19]. These assays measure the reduction in luciferase reporter gene expression levels in TZM-bl cells following a single round of virus infection. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated as the serum dilution that resulted in a 50% reduction in relative luminescence units compared with the virus control wells after the subtraction of cell control relative luminescence units. Viruses tested included tier 1A viruses SF162.LS (clade B) and MW965.26 (clade C) and tier 1B viruses DJ263.8 (clade A), Bal.26 (clade B) and TV1.21 (clade C). Murine leukemia virus (MuLV) negative controls were included in all assays.

Results

Env trimer stability in various adjuvants

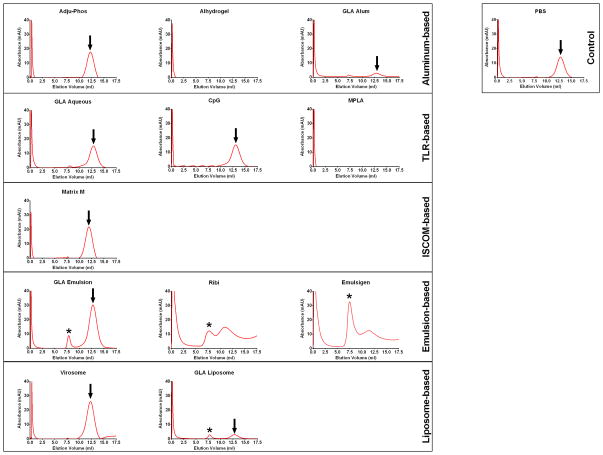

Twelve adjuvants from various classes were used in this study, including aluminum-based [Adju-Phos, Alhydrogel, Glucopyranosyl Lipid Adjuvant (GLA)-alum], TLR-based (GLA-aqueous, CpG, MPLA), ISCOM-based (Matrix M), emulsion-based (GLA-emulsion, Ribi, Emulsigen) and liposome-based (virosome, GLA-liposome) adjuvants (Table 1). We first assessed Env trimer stability in these adjuvants after a 1-hour incubation at 37°C. We re-purified the Env trimer on mini Ni-NTA columns, and assessed for stability by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). SEC revealed absorbance peaks corresponding to a monodisperse gp140 trimer of the expected hydrodynamic radius for Adju-Phos, GLA-aqueous, CpG, Matrix M and virosomes adjuvants (Figure 1). These data suggest that the clade C gp140 trimer protein largely remained intact in these adjuvants. In contrast, emulsion-based adjuvants GLA-emulsion, Ribi and Emulsigen, as well as GLA-liposome, resulted in varying levels of protein aggregates (asterisks, Figure 1), suggesting that these adjuvants partially disrupted trimer structural integrity. Alhydrogel, GLA-alum, MPLA and GLA-liposome adjuvants exhibited minimal recovery of gp140 trimer (Figure 1). While it is unclear why this recovery was low in the MPLA and GLA-liposome adjuvants, the absence or low-recovery of gp140 trimer from Alhydrogel and GLA-alum, respectively, may have been due to adsorption of trimer to particulate aluminum present in these adjuvants. Interestingly, Adju-Phos did not exhibit this adsorption, suggesting that it bound the gp140 trimer less tightly. This was likely due to the trimer pI value (which is heterogeneous and ranges between 3.5–7.5, Crucell, unpublished data) and its negative charge at neutral pH. These data suggest that aqueous adjuvants preserved trimer stability better than emulsion-based adjuvants.

Figure 1. Size-exclusion chromatography profiles of clade C gp140 trimer re-purified from multiple classes of adjuvants.

Clade C gp140 trimer re-purified from multiple classes of adjuvants after a 1-hour 37°C incubation were assessed by SEC on a superose 6 column (GE Healthcare). (Arrows denote intact trimer signal and asteriks denote aggregate formation) [Virosomes also contain influenza neuraminidase (NA) and haemagglutinin (HA) proteins as part of their composition]

Guinea pig immunogenicity

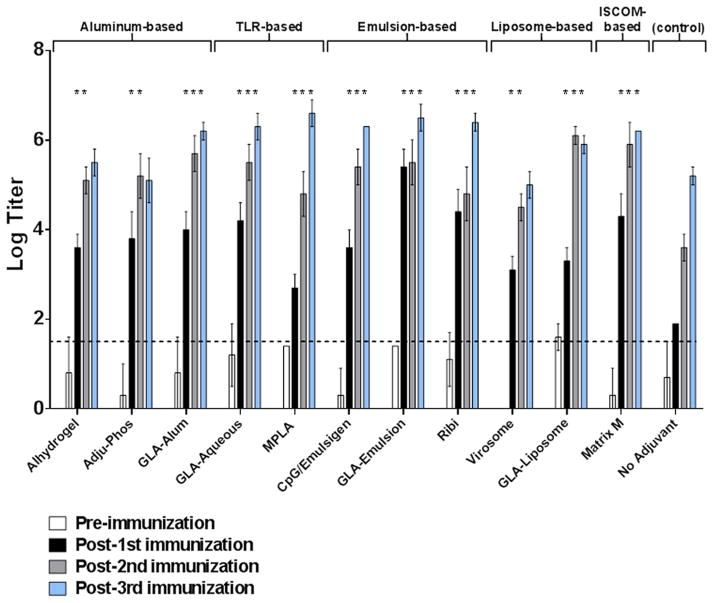

To assess the impact of various adjuvants on vaccine-elicited antibody responses, guinea pigs were immunized i.m. with the clade C gp140 trimer (100 μg/animal) in the presence or absence of the various adjuvants three times at monthly intervals, and serum samples were obtained 4 weeks after each immunization for antibody assays. CpG and Emulsigen adjuvants were combined as they have previously been shown induce higher levels of nAbs than each adjuvant on its own [20]. A control group received unadjuvanted clade C gp140 protein. The goal of these studies was not to perform a comprehensive antibody evaluation but rather to assess the impact of various adjuvants on several standard immunogenicity parameters. Binding gp140-specific antibodies were assessed 4 weeks after each immunization by end-point ELISAs and showed high titer binding antibodies in all immunized animals with the kinetics of the responses varying across the adjuvants (Figure 2). When compared to the unadjuvanted control group, all the adjuvanted groups induced significantly higher binding antibody responses after the first and second immunizations (P<0.05; unpaired t-tests) and maintained these higher responses at peak immunogenicity (post-3rd vaccination) (P<0.05; unpaired t-tests) with most adjuvants except Alhydrogel, Adju-Phos and virosomes (Figure 2). Virosomes appeared the least potent of the adjuvants tested, and the aluminum-based adjuvants Alhydrogel and Adju-Phos were less potent than other adjuvants after the 3rd immunization (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of clade C gp140 binding antibody responses generated in guinea pigs by multiple classes of adjuvants.

Serum samples obtained 4-weeks after each immunization were analyzed in endpoint ELISAs for binding antibody responses against clade C gp140. Horizontal broken line represents assay background threshold. Pre = pre-vaccination (*P<0.05; unpaired t-tests versus unadjuvanted control at each similar time point)

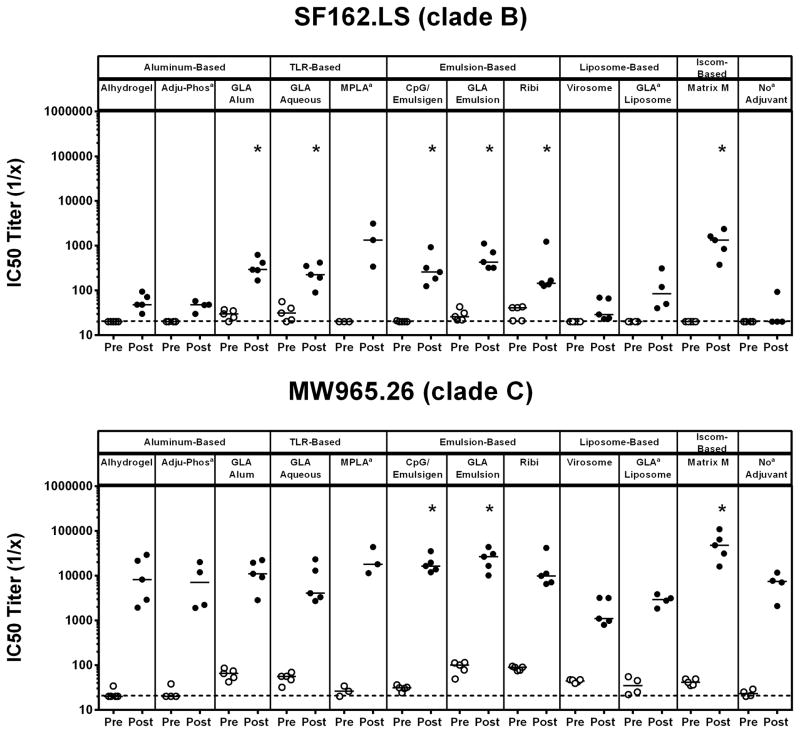

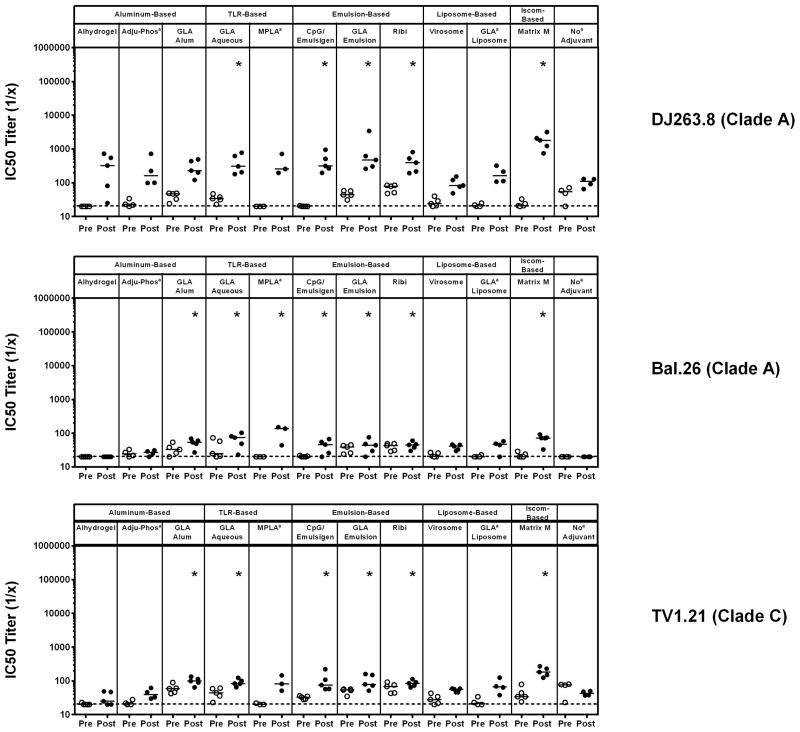

To evaluate the neutralization capacity of antibodies elicited in vaccinated guinea pigs, pre-vaccination and post-3rd vaccination samples were evaluated in TZM.bl virus neutralization assays [11, 12, 18] utilizing a standardized, multi-clade panel of tier 1 pseudoviruses comprising easy-to-neutralize tier 1A viruses [SF162.LS (clade B) and MW965.26 (clade C)] and intermediate tier 1B viruses [DJ263.8 (clade A), Bal.26 (clade B) and TV1.21 (clade C)]. Unadjuvanted clade C gp140 Env trimer elicited nAb responses against MW965.26 but induced marginal to no nAb responses against all other pseudoviruses tested (Figures 3 & 4). Higher magnitude nAb titers were observed by several of the adjuvants against SF162.LS (GLA-alum, GLA-aqueous, CpG/Emulsigen, GLA-emulsion, Ribi, and Matrix M; P<0.05, unpaired Mann Whitney test) and MW965.26 (CpG/Emulsigen, GLA emulsion, and Matrix M; P<0.05, unpaired Mann Whitney test) (Figure 3). Additionally, significantly higher nAb titers were observed in several adjuvanted groups when compared to the unadjuvanted group against DJ263.8 (GLA aqueous, CpG/Emulsigen, GLA emulsion, Ribi and Matrix M; P<0.05, unpaired Mann Whitney test), Bal.26 (GLA alum, GLA aqueous, MPLA, CpG/Emulsigen, GLA emulsion, Ribi and Matrix M; P<0.05, unpaired Mann Whitney test) and TV1.21 (GLA alum, GLA aqueous, CpG/Emulsigen, GLA emulsion, Ribi and Matrix M; P<0.05, unpaired Mann Whitney test) (Figure 4). Overall, no single adjuvant outperformed the others, although the aluminum-based adjuvants Adju-Phos and Alhydrogel elicited lower nAb responses, and virosomes failed to augment nAb responses compared with the unadjuvated clade C gp140 Env trimer.

Figure 3. Comparison of clade C gp140 TZM.bl Tier 1A nAb titers in guinea pigs using multiple classes of adjuvants.

Pre- and post-3rd vaccination guinea pig serum samples were evaluated in the TZM.bl nAb assay utilizing tier 1A viruses SF162.LS (clade B) and MW965.26 (clade C) to evaluate the neutralization capacity of antibodies elicited. Horizontal broken line represents assay background threshold. Pre = pre-vaccination; Post = post 3rd vaccination (* P<0.05 versus no adjuvant group; unpaired Mann Whitney test); [a n=5 for all groups except Adju-Phos (n=4), MPLA (n=3) and no Adjuvant (n=4)]

Figure 4. Comparison of clade C gp140 TZM.bl Tier 1B nAb titers in guinea pigs using multiple classes of adjuvants.

Pre- and post-3rd vaccination guinea pig serum samples were evaluated in the TZM.bl nAb assay utilizing tier 1A viruses SF162.LS (clade B) and MW965.26 (clade C) to evaluate the neutralization capacity of antibodies elicited. Horizontal broken line represents assay background threshold. Pre = pre-vaccination; Post = post 3rd vaccination (* P<0.05 versus no adjuvant group; unpaired Mann Whitney test); [a n=5 for all groups except Adju-Phos (n=4), MPLA (n=3) and no Adjuvant (n=4)]

Non-human primate immunogenicity

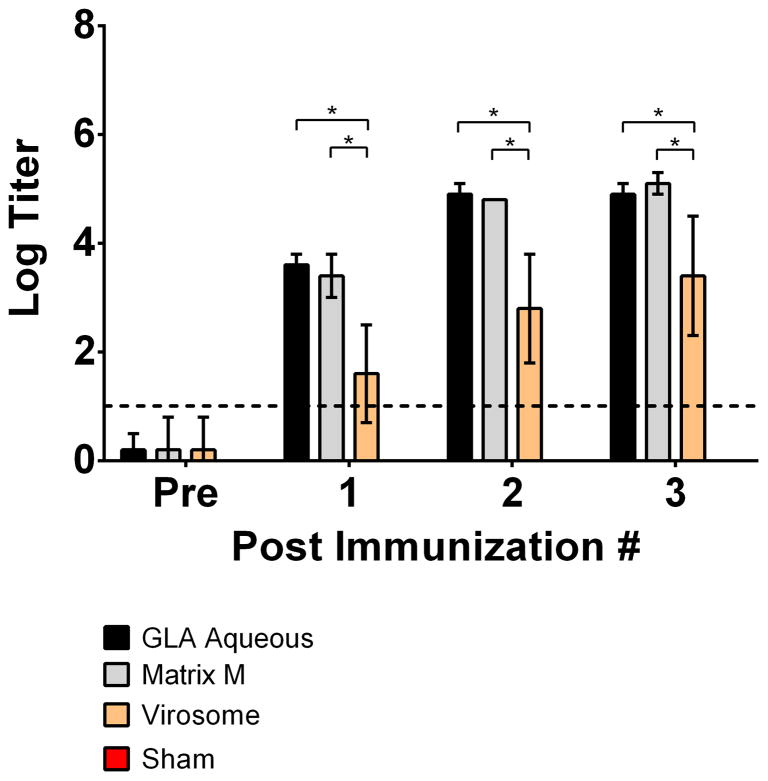

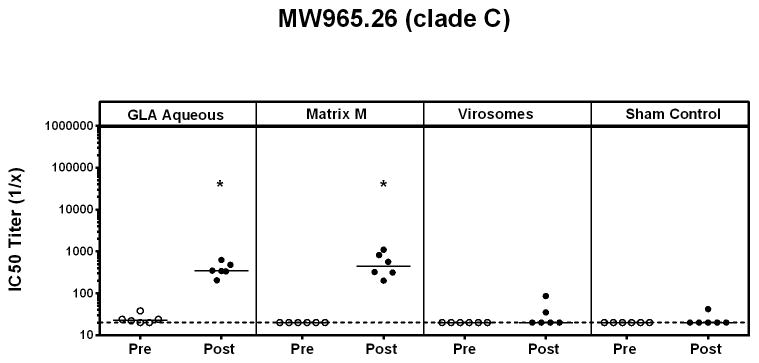

To investigate whether our findings in guinea pigs could be extended to non-human primates, we tested three adjuvants (Matrix M, GLA aqueous, virosomes) with the clade C gp140 trimer in rhesus macaques. These three adjuvants were selected to represent the spectrum of neutralizing antibody responses, ranging from low to high, observed in the guinea pig studies. Monkeys were immunized i.m three times at monthly intervals with clade C gp140 trimer (250 μg/animal) in the selected adjuvants, and serum samples obtained 4 weeks after each immunization for antibody assays. A PBS sham control group was included in the comparison. As in the guinea pig studies, the goal of these studies was to assess the impact of these adjuvants on standard immunogenicity parameters. Binding gp140-specific antibodies by end-point ELISAs were comparable with GLA-aqueous and Matrix M but weaker with virosomes, consistent with our guinea pig data (*P<0.05; unpaired t-tests) (Figure 5). The sham control group gave undetectable binding antibody responses (data not shown). In TZM.bl nAb assays, Matrix M and GLA-aqueous adjuvants induced significantly higher nAb responses against MW965.26 (*P<0.05; unpaired Mann Whitney test) versus sham controls (Figure 6). Clade C gp140 trimer with virosome adjuvant was unable to elicit any detectable tier 1A nAb responses in non-human primates.

Figure 5. Comparison of clade C gp140 binding antibody responses in non-human primates in select adjuvants.

Serum samples obtained 4-weeks after clade C gp140 immunizations in either Matrix M, GLA-Aqueous or virosome adjuvants were analyzed in endpoint ELISAs for binding antibody responses against clade C gp140. Horizontal broken line represents assay background threshold. Pre = pre-vaccination (*P<0.05; unpaired t-test)

Figure 6. Comparison of clade C gp140 TZM.bl Tier 1A nAb titers in select adjuvants in non-human primates.

Serum nAb titers in pre-vaccination and post 3rd-vaccination samples from GLA aqueous, Matrix M and virosome adjuvanted clade C gp140 were analyzed in the TZM.bl nAb assay. Horizontal broken line represents assay background threshold. (Pre = pre-vaccination; Post = post 3rd vaccination)(* P<0.05 versus sham control; unpaired Mann Whitney test)

Discussion

Adjuvants aim to enhance, sustain and direct the immunogenicity of vaccine immunogens. For HIV-1 vaccines, Env gp140 trimers have been shown to elicit greater nAb responses than Env gp120 monomers [9, 11, 13], but a head-to-head comparison of multiple adjuvants for HIV-1 Env trimers has been lacking. Several reports have previously attempted to evaluate antibody responses to HIV-1 gp140 trimers using different adjuvants [21–23] [24], but typically without assessing the stability of the Env gp140 trimer with adjuvant. In this report, we assessed the impact of multiple adjuvant formulations on clade C (C97ZA.012) gp140 trimer stability and immunogenicity. SEC was used to assess trimer integrity following re-purification from protein/adjuvant formulations at 37°C. We observed that emulsion-based adjuvants impacted the quaternary structure of the gp140 glycoprotein, resulting in partial aggregation and dissociation and presumably disruption of Env trimer structural integrity. This finding is relevant, since conformationally intact trimer may be critical for inducing optimal antibody responses. However, in the present study, the immunogenicity of multiple adjuvants, including emulsion-based adjuvants, appeared largely comparable. These data suggest that conformational epitopes may have still been present to some extent on trimer aggregates, or that the standard TZM.bl neutralization assays and ELISA binding assays were insufficient to evaluate the impact of trimer aggregation on immunogenicity. To provide a more definitive assessment of adjuvant impact on HIV-1 Env trimer conformation upon re-purification from adjuvants, surface plasmon resonance binding analyses with broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies recognizing conformational epitopes may provide additional insight. Furthermore, future studies evaluating the differences in protective efficacy of HIV-1 Env trimer immunogens with adjuvants in non-human primates may aid selection of adjuvants with the most clinical potential. While no in-depth immunological studies were performed in the current study, a recent report highlighting the role adjuvants play in directing serum cytokine and chemokine levels [25] will likely need to be assessed in the context of future studies and will provide further guidance in the selection of appropriate adjuvants for enhancing immunogenicity HIV-1 Env trimer vaccines.

While the gp140 trimer without adjuvant was still immunogenic, all adjuvants tested augmented binding and/or neutralizing antibody responses. In particular, neutralizing antibody responses were observed against both neutralization sensitive tier 1A viruses and intermediate tier 1B viruses indicating the capacity of each individual adjuvant to produce neutralizing antibodies against not only highly sensitive viral isolates, but also against slightly more resistant viruses from non-vaccine clades. No single adjuvant exhibited superiority over the others, although aluminum-based adjuvants Alhydrogel and Adju-Phos induced lower responses, and the virosome adjuvant only transiently augmented responses. The virosome adjuvant platform is clinically licensed in more than 40 countries in vaccines against hepatitis A and influenza and has been administered to more than 30 million individuals with excellent safety profiles [26]. The virosomes used in this study were simply mixed with HIV-1 Env, and thus it is possible that incorporation of antigens within virosomes may be necessary for its adjuvanticity.

Optimizing adjuvant selection for HIV-1 Env immunogens is a critical and understudied question in the HIV-1 vaccine field. Important parameters for adjuvant selection likely include: preservation of immunogen structure and key epitopes, intrinsic potency, clinical experience and safety and regulatory considerations. The extent to which various adjuvants differentially fulfill these criteria largely remains to be determined. The present studies represent an initial comparison of several broad classes of adjuvants. While no single adjuvant proved optimal in all categories, our data suggest that several adjuvants warrant further consideration for use with HIV-1 Env vaccine candidates.

Highlights.

We compare the stability and immunogenicity of a clade C HIV-1 Env trimer in 12 different adjuvants in guinea pigs

We find that oil-in-water emulsions resulted in partial aggregation and loss of structural integrity of the gp140 trimer

We find that multiple classes of adjuvants similarly augmented Env-specific binding and neutralizing antibody responses

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burton DR, Ahmed R, Barouch DH, Butera ST, Crotty S, Godzik A, et al. A Blueprint for HIV Vaccine Discovery. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barouch DH. Challenges in the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. Nature. 2008;455:613–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava IK, Ulmer JB, Barnett SW. Role of neutralizing antibodies in protective immunity against HIV. Human vaccines. 2005;1:45–60. doi: 10.4161/hv.1.2.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierson TC, Doms RW. HIV-1 entry and its inhibition. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2003;281:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-19012-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nara PL, Robey WG, Pyle SW, Hatch WC, Dunlop NM, Bess JW, Jr, et al. Purified envelope glycoproteins from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants induce individual, type-specific neutralizing antibodies. Journal of virology. 1988;62:2622–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2622-2628.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman PW, Eastman DJ, Wilkes DM, Nakamura GR, Gregory TJ, Schwartz D, et al. Comparison of the immune response to recombinant gp120 in humans and chimpanzees. Aids. 1994;8:591–601. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn NM, Forthal DN, Harro CD, Judson FN, Mayer KH, Para MF, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine to prevent HIV-1 infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2005;191:654–65. doi: 10.1086/428404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitisuttithum P, Gilbert P, Gurwith M, Heyward W, Martin M, van Griensven F, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trial of a bivalent recombinant glycoprotein 120 HIV-1 vaccine among injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2006;194:1661–71. doi: 10.1086/508748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beddows S, Franti M, Dey AK, Kirschner M, Iyer SP, Fisch DC, et al. A comparative immunogenicity study in rabbits of disulfide-stabilized, proteolytically cleaved, soluble trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp140, trimeric cleavage-defective gp140 and monomeric gp120. Virology. 2007;360:329–40. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khayat R, Lee JH, Julien JP, Cupo A, Klasse PJ, Sanders RW, et al. Structural characterization of cleaved, soluble human immunodeficiency virus type-1 envelope glycoprotein trimers. Journal of virology. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01222-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovacs JM, Nkolola JP, Peng H, Cheung A, Perry J, Miller CA, et al. HIV-1 envelope trimer elicits more potent neutralizing antibody responses than monomeric gp120. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:12111–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204533109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nkolola JP, Peng H, Settembre EC, Freeman M, Grandpre LE, Devoy C, et al. Breadth of neutralizing antibodies elicited by stable, homogeneous clade A and clade C HIV-1 gp140 envelope trimers in guinea pigs. Journal of virology. 2010;84:3270–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02252-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim M, Qiao ZS, Montefiori DC, Haynes BF, Reinherz EL, Liao HX. Comparison of HIV Type 1 ADA gp120 monomers versus gp140 trimers as immunogens for the induction of neutralizing antibodies. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2005;21:58–67. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed SG, Bertholet S, Coler RN, Friede M. New horizons in adjuvants for vaccine development. Trends in immunology. 2009;30:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity. 2010;33:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pashine A, Valiante NM, Ulmer JB. Targeting the innate immune response with improved vaccine adjuvants. Nature medicine. 2005;11:S63–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lore K, Karlsson Hedestam GB. Novel adjuvants for B cell immune responses. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2009;4:441–6. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832da082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mascola JR, D’Souza P, Gilbert P, Hahn BH, Haigwood NL, Morris L, et al. Recommendations for the design and use of standard virus panels to assess neutralizing antibody responses elicited by candidate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccines. Journal of virology. 2005;79:10103–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10103-10107.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montefiori DC. Measuring HIV neutralization in a luciferase reporter gene assay. Methods in molecular biology. 2009;485:395–405. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-170-3_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ioannou XP, Griebel P, Hecker R, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. The immunogenicity and protective efficacy of bovine herpesvirus 1 glycoprotein D plus Emulsigen are increased by formulation with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Journal of virology. 2002;76:9002–10. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9002-9010.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Svehla K, Mathy NL, Voss G, Mascola JR, Wyatt R. Characterization of antibody responses elicited by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate trimeric and monomeric envelope glycoproteins in selected adjuvants. Journal of virology. 2006;80:1414–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1414-1426.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buffa V, Klein K, Fischetti L, Shattock RJ. Evaluation of TLR agonists as potential mucosal adjuvants for HIV gp140 and tetanus toxoid in mice. PloS one. 2012;7:e50529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arias MA, Van Roey GA, Tregoning JS, Moutaftsi M, Coler RN, Windish HP, et al. Glucopyranosyl Lipid Adjuvant (GLA), a Synthetic TLR4 agonist, promotes potent systemic and mucosal responses to intranasal immunization with HIVgp140. PloS one. 2012;7:e41144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai RP, Seaman MS, Tonks P, Wegmann F, Seilly DJ, Frost SD, et al. Mixed adjuvant formulations reveal a new combination that elicit antibody response comparable to Freund’s adjuvants. PloS one. 2012;7:e35083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buglione-Corbett R, Pouliot K, Marty-Roix R, West K, Wang S, Lien E, et al. Serum cytokine profiles associated with specific adjuvants used in a DNA prime-protein boost vaccination strategy. PloS one. 2013;8:e74820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herzog C, Hartmann K, Kunzi V, Kursteiner O, Mischler R, Lazar H, et al. Eleven years of Inflexal V-a virosomal adjuvanted influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:4381–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambrecht BN, Kool M, Willart MA, Hammad H. Mechanism of action of clinically approved adjuvants. Current opinion in immunology. 2009;21:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Exley C, Siesjo P, Eriksson H. The immunobiology of aluminium adjuvants: how do they really work? Trends in immunology. 2010;31:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert SL, Yang CF, Liu Z, Sweetwood R, Zhao J, Cheng L, et al. Molecular and cellular response profiles induced by the TLR4 agonist-based adjuvant Glucopyranosyl Lipid A. PloS one. 2012;7:e51618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coler RN, Bertholet S, Moutaftsi M, Guderian JA, Windish HP, Baldwin SL, et al. Development and characterization of synthetic glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant system as a vaccine adjuvant. PloS one. 2011;6:e16333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krieg AM. Mechanisms and applications of immune stimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1999;1489:107–16. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mata-Haro V, Cekic C, Martin M, Chilton PM, Casella CR, Mitchell TC. The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science. 2007;316:1628–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1138963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovgren Bengtsson K, Morein B, Osterhaus AD. ISCOM technology-based Matrix M adjuvant: success in future vaccines relies on formulation. Expert review of vaccines. 2011;10:401–3. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans JT, Cluff CW, Johnson DA, Lacy MJ, Persing DH, Baldridge JR. Enhancement of antigen-specific immunity via the TLR4 ligands MPL adjuvant and Ribi.529. Expert review of vaccines. 2003;2:219–29. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]