Abstract

Background

The formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the heart during AMI amplifies the inflammatory response and mediates further damage. Glyburide has NLRP3-inhibitory activity in vitro, but requires very high doses in vivo, associated with hypoglycemia. The aim of this study was to measure the effects on the NLRP3 inflammasome of 16673-34-0, an intermediate substrate free of the cyclohexylurea moiety, involved in insulin release.

Methods and Results

We synthetized 16673-34-0 (5-Chloro-2-methoxy-N-[2-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)ethyl]benzamide) that displayed no effect on glucose metabolism. HL-1 cardiomyocytes were treated with LPS+ATP to induce the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome measured as increased caspase-1 activity and cell death, and 16673-34-0 prevented such effects. 16673-34-0 was well tolerated with no effects on the glucose levels in vivo. Treatment with 16673-34-0 in a model of AMI due to ischemia+reperfusion significantly inhibited the activity of inflammasome (caspase-1) in the heart by 90% (P<0.01) and reduced infarct size, measured at pathology (by >40%, P<0.01) and with troponin I levels (by >70%, P<0.01).

Conclusions

The small molecule 16673-34-0, an intermediate substrate in the glyburide synthesis free of the cyclohexylurea moiety, inhibits the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiomyocytes and limits the infarct size following myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in the mouse, without affecting glucose metabolism.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, inflammation, inflammasome, caspase-1

INTRODUCTION

An intense inflammatory response occurs during acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and the intensity of such response predicts adverse outcome.1 The release of intracellular content during ischemic necrosis leads to the formation of a macromolecular structure, the inflammasome, in leukocytes and resident cells, including cardiomyocytes.2-3 The activation of the inflammasome during injury greatly amplifies the inflammatory response by promoting the release of Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and cell death.2-3 NLRP3 (NALP3 or cryopyrin) is one of the intracellular sensors, part of the Nod-like receptor (NLR) family, that trigger the formation of the inflammasome and activation of caspase-1. During cell death, extracellular ATP leads to an efflux of K+ from cell and subsequent NLRP3 activation.2 Silencing or genetic deletion of NLRP3 in the mouse limited the infarct size in experimental AMI,3 suggesting NLRP3 inflammasome as a viable target for pharmacologic inhibition.4 The central role of NLRP3 in inflammatory diseases is highlighted in the cryopyrin-associated-period syndromes (CAPS), conditions in which constitutively active NLRP3 due to point-mutations leads to uncontrolled activation of the inflammasome leading to severe, often fatal, inflammatory disease.5 Clinically available NLRP3 inhibitors are, however, lacking. Glyburide, a widely used anti-diabetic drug (sulfonylurea) has NLRP3-inhibitory activity in vitro, but the use of glyburide as an inhibitor in vivo would require very several hundred-fold higher doses than those used in diabetes, which would be inevitably associated with lethal hypoglycemia.6 The cyclohexylurea moiety in the glyburide molecule is involved in the release of insulin by the pancreatic cells through inhibition of the KATP channels, yet it is not necessary for the NLRP3 inhibitory effect.6

The aim of this study was to measure the inhibitory effects of 16673-34-0, an intermediate substrate in the synthesis of glyburide which is free of the cyclohexylurea moiety involved in insulin release, on the NLRP3 inflammasome activity.

METHODS

Synthesis of 16673-34-0 (5-chloro-2-methoxy-N-[2-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)-ethyl]-benzamide)

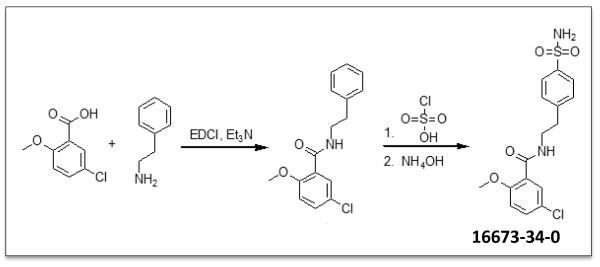

A recently reported glyburide analog containing a sulfonylchloride group has been shown to retain some of the anti-inflammatory activity of glyburide but with no effect on insulin.6 Due to the inherent instability of this moiety in vitro, however, we chose to design and synthesize a sulfonamide analog. 5-chloro-2-methoxybenzoic acid was reacted with 2-phenylethanamine in the presence of EDCI to form the amide intermediate, 5-chloro-2-methoxy-N-(2-phenylethyl)-benzamide, which was then treated with chlorosulfonic acid and aqueous ammonium hydroxide to afford 5-chloro-2-methoxy-N-[2-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)-ethyl]-benzamide (16673-34-0) in good yield (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Synthetic pathway of 16673-34-0.

A schematic for the synthesis of 16673-34-0 is provided.

Determination of the formation of inflammasome in vitro

J774A.1 cells, a murine macrophage cell line, were plated at 5×104 cells/well in a 96 multiwell plate for 24 hours in RPMI medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS)(Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The cells were primed with Escherichia coli 0111:B4 LPS (25 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich)(1 μg/ml) for 4 hours and then ATP (5 mM) for 30 minutes to induce the NLRP3 inflammasome formation. The supernatants were collected and levels of IL-1β were measured with a mouse IL-1β ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Princeton, NJ). To test the inhibitory effects of 16673-34-0 on NLRP3 inflammasome activation, cells were co-treated with 16673-34-0 (400μM) or Glyburide (400μM) at the time of ATP for 30 minutes, and IL-1β levels were used as read-out.

In separate experiments, immortalized adult murine cardiomyocytes (HL-1) cells, donated by Dr. Claycomb (Louisiana State University, New Orleans, LA) were used. Cells were cultured in Claycomb medium (Sigma-Aldrich) as suggested 7 and then primed with LPS (25 ng/mL) for 2 h and treated with ATP (5 mM) for 1 hour, as previously described, to induce NLRP3 inflammasome formation.3 HL-1 cells were then treated with 16673-34-0 (400μM) or glyburide (400μM) during the LPS priming phase, and then treated with ATP. Formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in HL-1 cells was determined and quantified by ASC aggregation (immunohistochemistry), caspase-1 activity (enzymatic activity) and cell death (trypan blue exclusion method), as previously described.3 Briefly, for immunohistochemistry, HL-1 cells were plated on 24×24 mm glass covers slip coated with gelatin/fibronectin (0.02–0.5%) at 2.5 × 105 in 35-mm dishes 24 h before the experiment. ASC expression was detected as circumscribed cytoplasmic perinuclear aggregates and expressed as ASC-positive cell over the total cells per field, and ASC aggregates were quantified blindly by two different investigators. As readout for the NLRP3 inflammasome activation, caspase-1 enzymatic activity and cell death were evaluated. Briefly, HL-1 cells (2 ×106 cells) were plated in 90-mm dishes and NLRP3 inflammasome formation was induced as described above. After treatments, to measure caspase-1 activity, the cells were washed, harvested, and frozen. The pellet was resuspended using RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing a mixture of protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich) and centrifuged at 16,200×g for 20 min. The supernatants were collected and the protein contents were quantified using the Bradford assay. The caspase-1 activity was determined by measuring the fluorescence produced by the cleavage of a fluorogenic substrate, A2452 (Sigma-Aldrich). The fluorescence was reported as arbitrary fluorescence units produced by 1 μg of sample per min (fluorescence/μg/min). Cell death in HL-1 cardiomyocytes was determined with a Trypan blue exclusion assay. Briefly, HL-1 cells were treated as described above, harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of Claycomb medium and incubated with 100 μL of 0.4% Trypan blue stain (Gibco) and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Trypan blue positive cells were deemed nonviable and the percentage of cell death was measured as the ratio of trypan blue positive cells over total cell number per field. We used also nigericin (Enzo Life Sciences Inc, Farmingdale, NY) 20μM, a pore forming toxin allowing for K+ efflux from the cell in a way similar to that seen with ATP binding to the P2X7 receptor. To determine the specificity for the NLRP3 inflammasome and exclude effects other inflammasomes, HL-1 cells (1×106) were plated in 35mm dishes and treated with flagellin or Poly-deoxyadenylic-deoxythymidylic acid sodium salt (Poly(dA:dT)) to induce the NLRC4 and the AIM2 inflammasomes respectively, which do not involve the activation of the NLRP3 sensor.2 Flagellin (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), isolated from Salmonella typhimurium strain 14028, 0.7ug/ml was added to the Claycomb medium in absence of fetal bovine serum (FBS). In order to induce the NLRC4 inflammasome, cells were first treated with flagellin using the Polyplus transfection kit (PULSin, New York, NY) for 4 hours and then treated with LPS (25ng/ml) for 1 h. Poly(dA:dT) is a repetitive double-stranded DNA molecule used to induce the AIM2 inflammasome formation. HL-1 cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) without FBS. Cells were incubated with Poly(dA:dT) (4ug/ml)(InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) for 6h and then treated with LPS (25ng/ml) for 1 h. To evaluate the inhibitory effects of 16673-34-0 on the formation of the NLRC4 and AIM2 inflammasomes, HL-1 cells were treated with 16673-34-0 (400μM) along with flagellin or Poly(dA:dT). Formation of the AIM2 and NLRC4 inflammasomes was determined and quantified by caspase-1 activity and cell death, as described above.

Administration of 16673-34-0 in the mouse in vivo

All the animal experiments were conducted under the guidelines of the “Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals” published by National Institutes of Health (revised 2011). The study protocol was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The 16673-34-0 was dissolved in DMSO (0.05-0.1 ml) and glyburide was used a control. In order to determine whether treatment with 16673-34-0 had any toxic effects in vivo, we measured weight, appetite and behavior after single and repeated intraperitoneal administrations in healthy control mice. Adult male (12-16 weeks old) out-bred Institute of Cancer Research (CD1) mice were supplied by Harlan Laboratories (Charles River, MA). We also measured capillary glucose levels (through prick stick of the tail and a point-of-care-testing glucometer) after single and repeated injections, over a range of concentration of 20-500 mg/Kg (N=4-6 per group).

Experimental model of acute myocardial infarction

Experimental acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was induced by transient myocardial ischemia for 30 min followed by reperfusion as described.8 Briefly, mice were orotracheally intubated under anesthesia (pentobarbital 50 to 70 mg/kg), placed in the right lateral decubitus position, then subjected to left thoracotomy, pericardiectomy, and ligation of the proximal left coronary artery. The ligated coronary artery was released after 30 min before closure of the thorax. Sham operations were performed wherein animals underwent the same surgical procedure without coronary artery ligation (N=6-12 per group). To evaluate the effect of 16673-34-0, groups of mice were treated with 16673-34-0 (100 mg/kg in 0.05 ml) or DMSO solution (0.05 ml, vehicle) or NaCl 0.9% solution (0.05 ml, control) given 30 minutes prior to surgery, then repeated at time of reperfusion and then every 6 hours for 3 additional doses, the mice were then sacrificed at 24 hours, the heart removed and processed for the assessment of caspase-1 in the tissue or infarct size measurement. Caspase-1 activity was measured on protein extracted from frozen hearts homogenized in RIPA buffer and then isolated and quantified as previously described.3 The Caspase-1 activity was measured and reported as described above.

Infarct size was measured using triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) (Sigma Aldrich) staining of viable myocardium 8 and the serum troponin I levels 24 hours after surgery were determined as marker of myocardial damage. Briefly, Mice were anesthetized and the blood was drawn from the inferior vena cava and collected in Vacutainer tubes (BD Vacutainer, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for the serum isolation. Mouse troponin I levels were determined by ELISA (Life Diagnostic Inc., West Chester, PA). In order to perform the infarct size staining, the heart was quickly removed after sacrifice and mounted on a Langendorff apparatus. The coronary arteries were perfused with 0.9% NaCl containing 2.5 mM CaCl2. After the blood was washed out, the ligated coronary artery was closed again, and approximately 1 ml of 1% Evans blue dye (Sigma Aldrich) was injected as a bolus into the aorta until the heart ‘not-at-risk’ turned blue. The heart was then removed, frozen, and cut into 6 transverse slices from apex to base of equal thickness (approximately 1 mm). The slices were then incubated in a 10% TTC isotonic phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 30 min. The infarcted tissue (appearing white), the risk zone (red), and the non-risk zone (blue) were measured by computer morphometry using Image Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

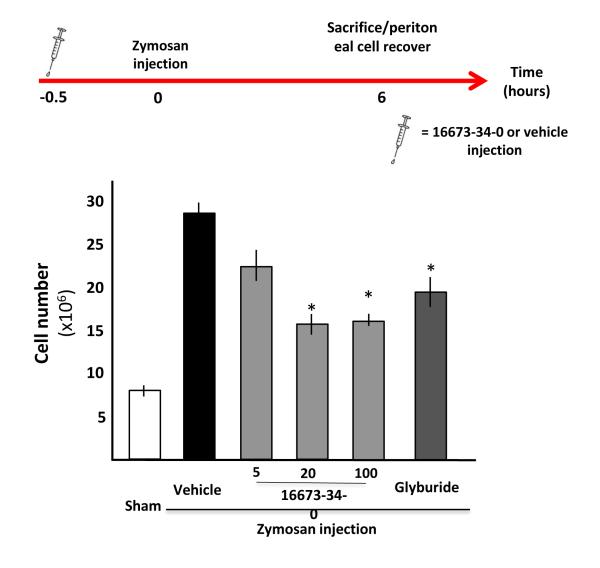

Experimental model of acute peritonitis in the mouse

Zymosan A triggers a NLRP3-inflammasome dependent inflammatory reaction when injected in the peritoneum.9 To determine the effects of 16673-34-0 on the NLRP3 inflammasome in vivo, independent of other potential effects on heart viability or function, we injected mice with 1 mg (0.1 ml) of zymosan A (Sigma-Aldrich) freshly prepared in sterile saline solution (0.9% NaCl) in the peritoneum, and after 6 hours mice were sacrificed by anesthesia overdose. The peritoneal cavity was immediately washed with 7 ml of cold PBS to recover peritoneal cells. Treatment with 16673-34-0 or equal volume of DMSO (vehicle) was administered 30 min before the stimulation with zymosan A at different doses (5, 20 and 100 mg/kg in 0.1 ml) to determine the inhibitory effects on leukocyte recruitment in the cavity (N=4-12 per group). In addition to 16673-34-0, glyburide (132.5 mg/kg, equimolar to 100 mg/kg of 16673-34-0) was used as a positive control. The total number of leukocytes in the peritoneal cavity was measured using a Thoma cell counting chamber (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis of data

All statistical analysis was be performed using SPSS 15.0 package for Windows (Chicago, IL). Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard error, and one-way ANOVA to compare between 3 or more groups followed by Bonferroni-corrected T tests for unpaired data was used. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan Meyer curves and the LogRank (Mantel-Cox) analysis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

16673-34-0 prevents the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro

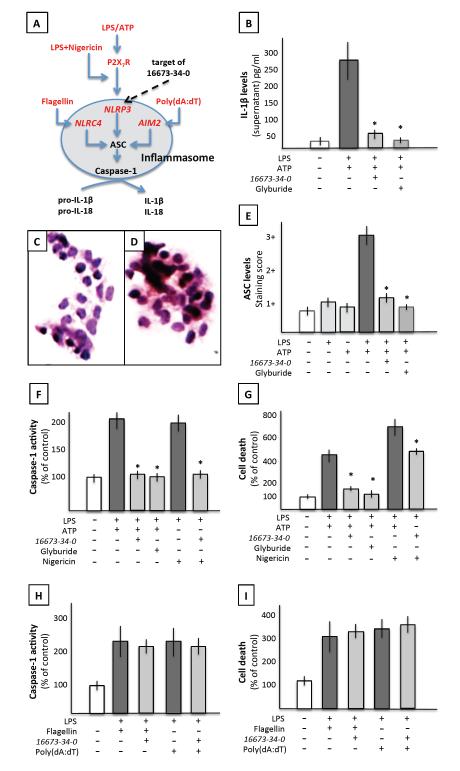

Cultured mouse macrophages were treated with LPS followed by ATP to induce the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and measure the release of mature IL-1β in the supernatant (Figure 2). Treatment with 16673-34-0 significantly limited IL-1β release after LPS and ATP challenge (Figure 2). To determine whether 16673-34-0 inhibited the formation of the inflammasome also in cardiomyocytes, cultured adult HL-1 cardiomyocytes were treated with LPS and ATP which induced the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome measured as macromolecular aggregates at immunocytochemistry for ASC, caspase-1 activity and inflammatory cell death, and all these effects were prevented by treatment with 16673-34-0 (Figure 2). An intermediate of 16673-34-0 lacking the sulfonyl residue (shown in Figure 1) also failed to inhibit caspase-1 and rescue the cells from inflammatory cell death in vitro (Supplemental Figure 1). ATP binding to the P2X7 receptor leads to K+ efflux to cell, accordingly the addition of nigericin, a pore forming toxin allowing for K+ efflux, to LPS led to the formation and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, also prevented by 16673-34-0 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Targeted inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome by 16673-34-0.

Panel A shows a schematic representation of the stimuli for the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the NLRC4 and AIM2 inflammasomes. Panel B shows increased interleukin-1β (IL-1β) release by cultured macrophages (J774A.1) in response to LPS/ATP, which is inhibited by 16673-34-0 or glyburide (*P<0.05 vs LPS/ATP). Panels C-E show ASC aggregation in cardiomyocytes in culture (HL-1) without stimulation (panel C) or following LPS/ATP (panel D), with a quantification in panel E showing inhibition of ASC aggregate formation following LPS/ATP by treatment with 16673-34-0 or glyburide (*P<0.05 vs LPS/ATP). Panels F and G show increased caspase-1 activity and cell death following LPS/ATP or LPS/nigericin in cardiomyocytes, also prevented by treatment with 16673-34-0 or glyburide (*P<0.05 vs LPS/ATP or LPS/Nigericin). Panels H and I show an increase in caspase-1 activity and cell death, respectively, following stimulation of the NLRC4 or AIM2 inflammasomes with flagellin or Poly(dA:dT), respectively, and a lack of inhibitory effect by 16673-34-0.

The activation of inflammasomes that use sensors other than NLRP3 (AIM2 – triggered by exogenous dual strand DNA – or NLRC4 – triggered by flagellin) were not inhibited by 16673-34-0 (Figure 2), showing a selective effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome.

16673-34-0 has no effects on glucose control in the mouse in vivo

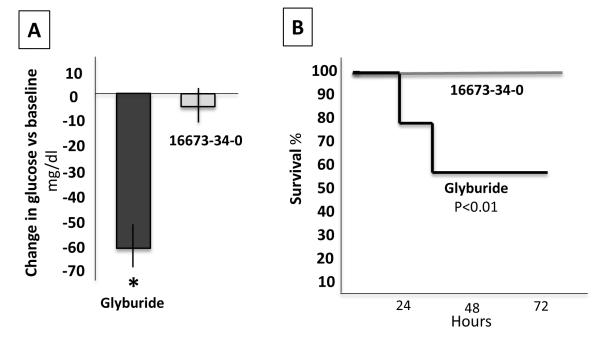

At difference with glyburide, 16673-34-0 lacks the cycloxyurea moiety involved in the activation of the release of insulin, as such 16673-34-0 was well tolerated when given as high as 500 mg/kg for 7 days showing no significant effects on survival, body weight, appetite or behavior, and had no effects on plasma glucose levels, whereas glyburide led to a significant reduction in glucose levels as early as 2 hours and it was lethal within 3 days in 50% of mice treated with 100 mg/kg every 6 hours for 3 doses, and in 100% in 3 days after daily doses of 500 mg/kg, due to severe hypoglycemia in all cases (Figure 3). These data show that 16673-34-0 has no measurable effect on glucose control in the mouse, as expected due to the structural lack of the cycloxyurea moiety.

Figure 3. 16673-34-0 has no effects on glucose control in the mouse in vivo.

Panel A shows a lack of significant changes in glucose levels 2 hours after a single dose of 16673-34-0 (100 mg/kg) and a significant reduction after glyburide 132.5 mg (equimolar to 16673-34-0 100 mg/kg). Panel B shows a 50% mortality in healthy mice treated with glyburide 132.5 mg every 6 hours for 24 hours, and lack of any effects of 16673-34-0 100 mg/kg every 6 hours for 24 hours (P<0.01).

16673-34-0 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome in acute myocardial infarction in the mouse

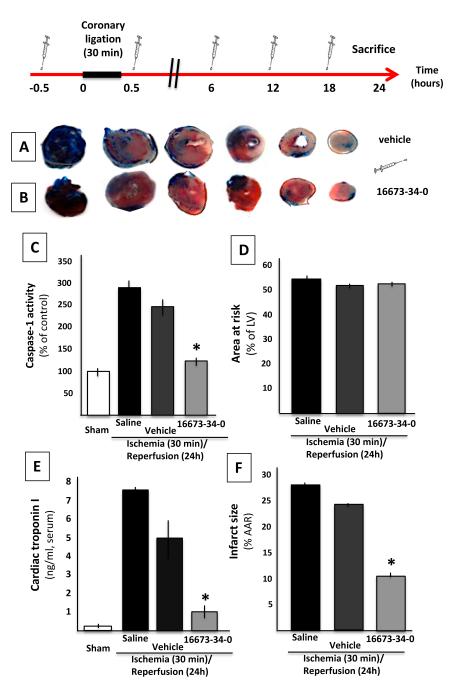

To determine whether 16673-34-0 inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome in vivo, we used a model of severe regional myocardial ischemia due to surgical coronary ligation (30 minutes) followed by reperfusion (24 hours). Treatment with 16673-34-0 led to a significant >90% reduction in caspase-1 activity (reflective of the formation of an active inflammasome) in the heart tissue measured 24 hours after ischemia (Figure 4). Treatment with 16673-34-0 also led to a significant reduction in the infarct size measured with TTC (>40% reduction) or troponin I levels (>70% reduction) when compared with vehicle alone (Figure 4). These data show that 16673-34-0 possesses powerful cardioprotective properties mediated by inhibition of the inflammasome. Treatment with an equivalent dose of glyburide led to a 100% mortality in mice with AMI (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 4. 16673-34-0 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome in acute myocardial infarction in the mouse.

A schematic of the study design is provided. Panels A and B show representative images of TTC stains for infarct size measurement in vehicle- and 16673-34-0-treated mice. Panel C shows a significant increase of caspase-1 activity in the heart 24 hours following ischemia-reperfusion, and a significant (>90%) reduction with 16673-34-0. Panels D and E show a significant (>40%) reduction in infarct size with 16673-34-0, without differences in the area-at-risk. Panel F shows a significant increase in serum cardiac troponin I levels 24 hours after ischemia reperfusion, and significantly lower levels (-70%) in mice treated with 16673-34-0.

16673-34-0 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome in a model of acute peritonitis in the mouse

To determine whether 16673-34-0 inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome in vivo in a model in which activation of the inflammasome is independent of the effects of myocardial ischemia/infarction, we used Zymosan A and induced a peritonitis which is known to be dependent upon intact NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and release of active IL-1β. Pre-treatment with 16673-34-0 (5, 20 and 100 mg/kg) limited the severity of the peritonitis measured as the intensity of the leukocyte infiltration in the peritoneal cavity, in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5). These data show that 16673-34-0 inhibits the formation and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the mouse in vivo, and suggests that the effects seen in the AMI model are likely due to a direct inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome and not exclusively to a reduction on the infarct size.

Figure 5. 16673-34-0 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome in a model of acute peritonitis in the mouse.

A schematic of the study design is provided. A significant increase in the number of cells recovered from the peritoneal lavage was seen 6 hours after treatment with zymosan, and it was significantly reduced by treatment with 16673-34-0 or glyburide.

DISCUSSION

The NLRP3 inflammasome is a central mediator in the inflammatory response to tissue injury.2 In acute myocardial infarction, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome amplifies cardiac injury and promotes heart failure.3 In the current report, we present preliminary data on an intermediate in the synthetic pathway of glyburide, 16673-34-0, as a novel inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Glyburide possesses NLRP3 inflammasome inhibiting properties in vitro, however the dose required for this effect in vivo leads to severe and lethal hypoglycemia in the mouse thus limiting its clinical use. When compared with glyburide, 16673-34-0 lacks the cycloxyurea moiety and therefore is not a sulfonylurea and it is not active on the KATP channels that regulate insulin release from pancreatic β-cells. We hereby show that 16673-34-0 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro and limits NLRP3 inflammasome mediated injury in a model of acute myocardial infarction and acute peritonitis in the mouse.

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first pharmacologic inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome to be tested in vivo. A prior study from our group had shown that silencing of NLRP3 expression using systemic high doses of small interfering RNA reduced infarct size and limited cardiac dilatation in the experimental AMI model in the mouse.3 Sandanger at al. showed that the mouse with genetic deletion of NLRP3 (knock-out) also has smaller infarct in the AMI model compared with the wild-type.10-11 The finding of a protective effect of this pharmacologic NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor confirms the central role in AMI. These findings are also in line with the data showing a critical role in AMI of ASC and caspase-1, the scaffold and the effector enzyme in the inflammasome complex, respectively.12-13

Lamkamfi et al.6 have shown that glyburide’s inhibitory activity on the inflammasome was limited to the NLRP3 inflammasome, we confirm that also 16673-34-0, which shares most of the structure of glyburide, has inhibitory effects on the NLRP3 inflammasome but not on the NLRC4 or AIM2 inflammasomes.2 The exact mechanism by which 16673-34-0 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome is not entirely clear, and molecular interactions are not explored in the current study. It is however apparent that 16673-34-0 inhibits the aggregation of the NLRP3 inflammasome following LPS and K+ efflux (but not after other NLPR3-independent stimuli) suggesting that it impedes the polymerization of the structure by interfering either with the activation of NLRP3 or the aggregation with the scaffold ASC. Considering that multiple diverse stimuli activate NLRP3 yet the effects of 16673-34-0 is maintained independent of which one it is, it suggests that 16673-34-0 interferes with downstream events involved in either NLRP3 conformational changes secondary to activation or aggregation to ASC. This effect is unlikely to be secondary to inhibition of NLRP3 ATP-se activity.6 Recruitment of caspase-1 and its activation in the inflammasome appears not be inhibited if the stimulus is NLRP3-independent and thus 16673-34-0 is not a caspase-1 inhibitor.

From a clinical standpoint, 16673-34-0 may represent a completely novel approach in the treatment of AMI. Treatment with 16673-34-0 may limit the inflammatory response to initial injury and prevent the second wave of inflammatory injury to the heart.4,14 While more and more patients are surviving their first or recurrent AMI, many patients still develop heart failure within the first year and ultimately die of cardiac death prematurely. Inhibiting the NRLP3 inflammasome may represent an entirely new approach at reducing cardiac injury during AMI with the intent of preventing early and late mortality.14 Recent pilot studies in AMI with blocker of IL-1β, the primary product of an active inflammasome, have shown the potential for prevention of late occurrence of heart failure with this approach.14-16

The importance of the NRLP3 inflammasome is however in no way limited to the field of cardiology. Genetic mutations in NRLP3 are the pathological basis of autoinflammatory disease called cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes.5 Activation of the NRLP3 inflammasome and production of IL-1β are considered central in acute and chronic inflammatory and degenerative diseases such as rheumatoid and gouty arthritis, diabetes, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer, and therefore the potential applications of 16673-34-0 are many.17-18 Additional studies will be necessary to determine the mechanism(s) by which 16673-34-0 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome, explore formulation, dosing, scheduling to optimize NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition, and determine potential off-target or toxic effects.

CONCLUSION

The small molecule 16673-34-0, an intermediate substrate in the synthesis of glyburide which is free of the cyclohexylurea moiety involved in insulin release, inhibits the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiomyocytes in vitro, and ameliorates post-myocardial infarction remodeling and peritonitis in the mouse in vivo, without affecting glucose levels. 16673-34-0 may represent a lead compound in a novel class of pharmacologic inhibitors of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. An 16673-34-0 intermediate lacking the sulfonyl residue has no inhibitory effects on the NLRP3 inflammasome

The figure shows increased caspase-1 activity (top panel) and cell death (bottom panel) following LPS/ATP in cardiomyocytes, prevented by treatment with 16673-34-0 but not by an intermediate compound in the synthesis which lacks the sulfonyl residue (*P<0.05 vs LPS/ATP). P values between 16673-34-0 and intermediate compound are shown in the figure.

Supplemental Figure 2. Effects of glyburide or 16673-34-0 on survival after ischemia-reperfusion surgery.

The figure shows a 100% mortality in mice with acute myocardial infarction treated with glyburide 132.5 mg every 6 hours for 24 hours (P<0.001 vs those treated with 16673-34-0 or vehicle).

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Dr. Toldo, Dr. Mezzaroma, Dr. Van Tassell and Dr. Abbate are supported by grants from the American Heart Association. Dr. Rose was supported by a VCU School Medicine Summer Research Award. Dr. Zhang is supported by an NIH R01 grant (AG041161).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: None of the authors have any conflict of interest to disclose pertinent to the current project.

REFERENCES

- 1).Frangogiannis NG. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2012;110:159–173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Flavell R. Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature. 2012;481:278–286. doi: 10.1038/nature10759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Mezzaroma E, Toldo S, Farkas D, Seropian IM, Van Tassell BW, Salloum FN, Kannan HR, Menna AC, Voelkel NF, Abbate A. The inflammasome promotes adverse cardiac remodeling following acute myocardial infarction in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19725–19730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108586108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Toldo S, Mezzaroma E, Abbate A. Interleukin-1 blockade in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure: ready for clinical translation? Transl Med. 2013;3:e114. [Google Scholar]

- 5).Wilson SP, Cassel SL. Inflammasome-mediated autoinflammatory disorders. Postgrad Med. 2010;122:125–133. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Lamkanfi M, Mueller JL, Vitari AC, Misaghi S, Fedorova A, Deshayes K, Lee WP, Hoffman HM, Dixit VM. Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/NALP3 inflammasome. J Cell Biol. 2009:18761–18770. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ., Jr HL-1 cells: A cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Toldo S, Seropian IM, Mezzaroma E, Van Tassell BW, Salloum FN, Lewis EC, Voelkel N, Dinarello CA, Abbate A. Alpha-1 antitrypsin inhibits caspase-1 and protects from acute myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Kumar H, Kumagai Y, Tsuchida T, Koenig PA, Satoh T, Guo Z, Jang MH, Saitoh T, Akira S, Kawai T. Involvement of the NLRP3 inflammasome in innate and humoral adaptive immune responses to fungal beta-glucan. J Immunol. 2009;183:8061–8067. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Sandanger Ø , Ranheim T, Vinge LE, Bliksøen M, Alfsnes K, Finsen AV, Dahl CP, Askevold ET, Florholmen G, Christensen G, Fitzgerald KA, Lien E, Valen G, Espevik T, Aukrust P, Yndestad A. The NLRP3 inflammasome is up-regulated in cardiac fibroblasts and mediates myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:164–174. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Mezzaroma E, Toldo S, Abbate A. Role of NLRP3 (cryopyrin) in acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:225–226. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Kawaguchi M, Takahashi M, Hata T, et al. Inflammasome activation of cardiac fibroblasts is essential for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2011;123:594–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Merkle S, Frantz S, Schön MP, Bauersachs J, Buitrago M, Frost RJ, Schmitteckert EM, Lohse MJ, Engelhardt S. A role for caspase-1 in heart failure. Circ Res. 2007;100:645–653. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260203.55077.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Van Tassell BW, Toldo S, Mezzaroma E, Abbate A. Targeting Interleukin-1 in heart disease. Circulation. 2013;128:1910–1923. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Abbate A, Kontos MC, Grizzard JD, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Van Tassell BW, Robati R, Roach LM, Arena RA, Roberts CS, Varma A, Gelwix CC, Salloum FN, Hastillo A, Dinarello CA, Vetrovec GW, VCU-ART Investigators Interleukin-1 blockade with anakinra to prevent adverse cardiac remodeling after acute myocardial infarction (Virginia Commonwealth University Anakinra Remodeling Trial [VCU-ART] Pilot study) Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Abbate A, Van Tassell BW, Biondi-Zoccai G, Kontos MC, Grizzard JD, Spillman DW, Oddi C, Roberts CS, Melchior RD, Mueller GH, Abouzaki NA, Rengel LR, Varma A, Gambill ML, Falcao RA, Voelkel NF, Dinarello CA, Vetrovec GW. Effects of interleukin-1 blockade with anakinra on adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure after acute myocardial infarction [from the Virginia Commonwealth University-Anakinra Remodeling Trial (2) (VCU ART2) pilot study] Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1394–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Dinarello CA, Simon A, van der Meer JW. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:633–652. doi: 10.1038/nrd3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).López-Castejón G, Pelegrín P. Current status of inflammasome blockers as anti-inflammatory drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:995–1007. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.690032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. An 16673-34-0 intermediate lacking the sulfonyl residue has no inhibitory effects on the NLRP3 inflammasome

The figure shows increased caspase-1 activity (top panel) and cell death (bottom panel) following LPS/ATP in cardiomyocytes, prevented by treatment with 16673-34-0 but not by an intermediate compound in the synthesis which lacks the sulfonyl residue (*P<0.05 vs LPS/ATP). P values between 16673-34-0 and intermediate compound are shown in the figure.

Supplemental Figure 2. Effects of glyburide or 16673-34-0 on survival after ischemia-reperfusion surgery.

The figure shows a 100% mortality in mice with acute myocardial infarction treated with glyburide 132.5 mg every 6 hours for 24 hours (P<0.001 vs those treated with 16673-34-0 or vehicle).