Abstract

Thymosin beta 4 (Tβ4) and thymosin beta 10 (Tβ10) are two members of the beta-thymosin family involved in many cellular processes such as cellular motility, angiogenesis, inflammation, cell survival and wound healing. Recently, a role for beta-thymosins has been proposed in the process of carcinogenesis as both peptides were detected in several types of cancer. The aim of the present study was to investigate the expression pattern of Tβ4 and Tβ10 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). To this end, the expression pattern of both peptides was analyzed in liver samples obtained from 23 subjects diagnosed with HCC. Routinely formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded liver samples were immunostained by indirect immunohistochemistry with polyclonal antibodies to Tβ4 and Tβ10. Immunoreactivity for Tβ4 and Tβ10 was detected in the liver parenchyma of the surrounding tumor area. Both peptides showed an increase in granular reactivity from the periportal to the periterminal hepatocytes. Regarding HCC, Tβ4 reactivity was detected in 7/23 cases (30%) and Tβ10 reactivity in 22/23 (96%) cases analyzed, adding HCC to human cancers that express these beta-thymosins. Intriguing finding was seen looking at the reactivity of both peptides in tumor cells infiltrating the surrounding liver. Where Tβ10 showed a strong homogeneous expression, was Tβ4 completely absent in cells undergoing stromal invasion.

The current study shows expression of both beta-thymosins in HCC with marked differences in their degree of expression and frequency of immunoreactivity. The higher incidence of Tβ10 expression and its higher reactivity in tumor cells involved in stromal invasion indicate a possible major role for Tβ10 in HCC progression.

Key words: β-thymosins, Tβ4, Tβ10, hepatocellular carcinoma, stromal invasion

Introduction

Thymosins are a group of naturally occurring, small bioactive peptides. After their isolation from the calf thymus in 1966,1 they have been divided into three distinct classes based on their isoelectric point: alpha thymosins (pH<5.0), beta thymosins (pH between 5.0 and 7.0) and gamma thymosins (pH>7.0).2 In humans, three beta thymosins have been identified to date: thymosin β4, β10 and β15.3 Thymosin beta 4 (Tβ4) is considered to be the most abundant subtype (70-80%) of the beta thymosin family in mammalian tissues.4 This 43 amino acid peptide is seen as the main actin monomer sequestering molecule. Alongside its pivotal role in cellular motility, Tβ4 has a broad range of other biological activities, mainly focused on angiogenesis, inflammation, cell survival and wound healing.5 Thymosin beta 10 (Tβ10) is another member of the beta thymosin family. This 43 amino acid peptide is generally reported to be much less abundant (5-10%) and is, together with Tβ4, the main actin sequestering molecule.6 Although both peptides are highly homologues (up to 77%), they exert different effects on processes such as angiogenesis and apoptosis:7 as Tβ4 promotes angiogenesis, Tβ10 has been shown to inhibit angiogenesis by interfering with the RAS oncoprotein;8 whereas Tβ4 plays an important role as anti-apoptotic peptide, overexpression of Tβ10 has been associated with accelerated apoptosis.9 Over the past few years, several studies have been conducted on the expression pattern of beta-thymosins in different organs in adulthood10-12 and their role in embryogenesis and in carcinogenesis. It has been shown that Tβ4 is highly expressed during embryonic development, followed by a downregulation during adulthood and again an upregulation in several tumors. This suggests that tumor cells might utilize fetal programs, including Tβ4 synthesis.13 A 2012 study by Nemolato et al. revealed a strong Tβ4 expression in epithelial cells undergoing epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) in colorectal cancer. This high expression of Tβ4 was associated with a downregulation of E-cadherin, which might implicate a role for Tβ4 in carcinogenesis and metastasis.14 Besides, also Tβ10 expression has been detected in several tumors. Intensity of Tβ10 expression levels correlated significantly with the stage of both breast15 and lung cancer.16 Blocking of this peptide in thyroid cancer resulted in a significant decrease in tumor growth.17 These results implicate a possible role for both Tβ4 and Tβ10 as molecular markers and therapeutic targets in several tumors.

On the basis of these data, suggesting that beta-thymosins might play a pivotal role in carcinogenesis, this study was focused on the analysis of the expression pattern of Tβ4 and Tβ10 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Materials and Methods

The study included archival paraffin-embedded liver samples obtained from 23 consecutive subjects diagnosed with HCC in the Department of Pathology of the University Hospital of Cagliari. In order to avoid sampling variability in Tβ4 and Tβ10 expression, only surgically-resected tumors were included. The age of the subjects (15 males and 8 females) ranged from 43 up to 76 years. The main clinical data of the HCC cases are reported in Table 1. As a control group, we used 9 liver biopsies from adult subjects with very mild pathological changes, that were immunostained for Tβ4 and Tβ10.

Table 1.

Clinical data of 23 patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Case Nº | Age | Gender | Follow up until death (months) | Follow up until last hospitalization (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 61 | M | 49.9 | |

| 2* | 57 | F | 23.2 | |

| 3* | 54 | F | 7.1 | |

| 4 | 66 | M | 52.1 | |

| 5 | 69 | M | 56.3 | |

| 6 | 76 | F | 14.9 | |

| 7 | 66 | M | 8.3 | |

| 8 | 58 | M | 45.3 | |

| 9 | 44 | M | 0.2 | |

| 10 | 69 | M | 9.5 | |

| 11 | 70 | F | 41.1 | |

| 12 | 76 | F | 0.2 | |

| 13 | 54 | M | 56.0 | |

| 14 | 64 | M | 40.3 | |

| 15 | 74 | M | 65.0 | |

| 16* | 70 | M | 2.0 | |

| 17 | 70 | M | 10.7 | |

| 18 | 48 | M | 73.4 | |

| 19 | 43 | M | 7.3 | |

| 20* | 69 | F | 47.2 | |

| 21 | 63 | F | 3.5 | |

| 22 | 48 | M | 0.3 | |

| 23 | 72 | F | 33.2 |

*Multiple samples analyzed.

All liver samples were routinely formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded; immunostaining of 4 µm sections was performed by indirect immunohistochemistry. For each tumor, two samples were immunostained with either Tβ4 or Tβ10 antibody. In case 1, 2, 3, 16 and 20 multiple samples were analyzed, in order to verify if both peptides were homogeneously expressed throughout the tumor mass. All slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 0,3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in methanol. Subsequently, slides were subjected to antigen retrieval by heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) using the target retrieval solution (Dako TRS pH 6.1; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for 30 min. This was followed by incubation with a polyclonal antibody to Tβ4 (Bachem-Peninsula Lab, San Carlos, CA, USA, catalog number T-4848, diluted 1:600) or Tβ10 (Bachem-Peninsula Lab, catalog number ab14338, diluted 1:400). Slides were extensively washed and subjected to a biotinylated secondary antibody (Envision kit). After secondary antibody incubation, streptavidin peroxidase (HRP) and AEC chromogen were added. The AEC chromogen formed a red end-product at the site of target antigen. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted. As a positive control, sections of adult human liver were utilized.

A semi-quantitative grading system was used for the evaluation of Tβ4 and Tβ10 immunoreactivity, based on the percentage of immunoreactive tumor cells: 0 (<5%); 1 (5-10%); 2 (10-50%); 3 (>50%).

Results

Immunoreactivity for Tβ4 and Tβ10 was observed in three patterns: a homogeneous staining diffusely distributed over the entire cytoplasm of the hepatocytes; a punctuated and granular staining localized in the cytoplasm; a granular staining localized in perinuclear regions, which possibly represents a localization at the trans-Golgi network. In all cases, no nuclear expression was detected.

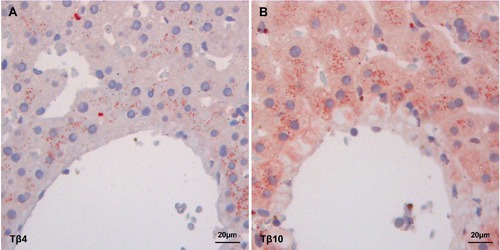

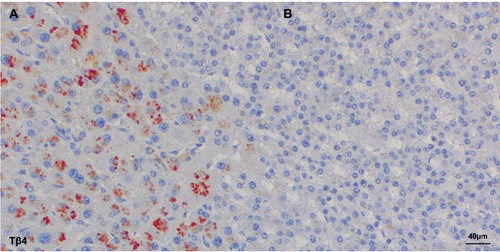

Control group

Both Tβ4 and Tβ10 expression was detected in all 9 liver biopsies of normal livers without cancer. Tβ4 appeared as large granules in the cytoplasm, different in shape and size. The staining was not homogeneously diffuse to the entire parenchyma, but it was mainly stored in periterminal hepatocytes (zone 3 of the acinus) (Figure 1A), while a minor degree of reactivity was detected in periportal hepatocytes (zone 1). Immunostaining for Tβ10 was characterized by a diffuse cytoplasmic reactivity in the vast majority of hepatocytes of all acinar zone. Morover, a mild granular immunoreactivity was detected in zone 3 hepatocytes (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Immunoreactivity of Tβ4 and Tβ10 (stained in red) in the control group. A) Tβ4 granular staining localized in the periterminal hepatocytes. B) Tβ10 homogeneous and granular staining in the cytoplasm of periterminal hepatocytes.

Normal liver parenchyma surrounding hepatocellular carcinoma

Both Tβ4 and Tβ10 expression was detected in the liver parenchyma surrounding HCC in all cases analyzed. Tβ4 appeared as large granules in the cytoplasm, different in shape and

size (Figure 2B). Tβ10 was seen as cytoplasmic granules or as a homogeneous staining over the entire cytoplasm (Figure 2D). A substantial difference was observed in the zonation pattern of Tβ4 and Tβ10. The degree of granular reactivity for Tβ4 (Figure 2A) and Tβ10 (Figure 2C) increased from the periportal hepatocytes (zone 1 of acinus) towards the periterminal hepatocytes (zone 3 of acinus). Especially Tβ4 showed a high increase in immunoreactivity towards the terminal vein. No zonation pattern was detected for the homogeneous expression of Tβ10, that was diffusely expressed over the entire liver parenchyma surrounding the tumor mass.

Figure 2.

Expression of Tβ4 and Tβ10 (stained in red) in the same field of normal surrounding liver parenchyma. A) Tβ4 shows an increase in the degree of immunostaining from the periportal to the periterminal acinar zones; PT, portal tract. B) A strong granular expression pattern for Tβ4 is observed in the periterminal hepatocytes; TV, terminal vein. C) Two expression patterns of Tβ10 are observed: granular reactivity in periterminal hepatocytes and homogeneous reactivity without a zonation pattern; PT, portal tract. D) Tβ10 is both granular and homogeneously expressed in the hepatocytes surrounding the terminal vein; TV, terminal vein.

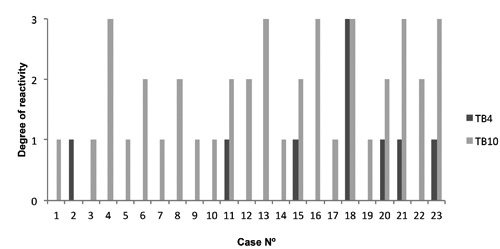

Hepatocellular carcinoma

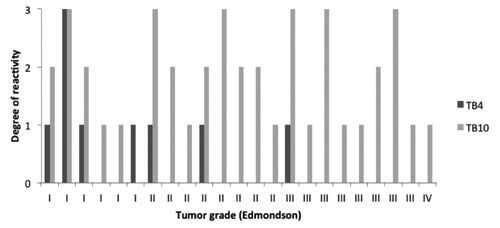

Immunoreactivity for Tβ4 was detected in 7 out of 23 (30%) HCC samples. Grade 1 in 6 cases and grade 3 in 1 case (Figure 3). Tβ10 reactivity was observed in 22 out of 23 (96%) HCC samples. Grade 1 in 9 cases, grade 2 in 7 cases and grade 3 in 6 cases (Figure 3). For both beta-thymosins, no relationship was found between the degree of immunoreactivity and age or gender of the subjects. Immunostaining for both peptides was predominantly homogeneous and diffusely distributed over the entire cytoplasm. In the tumor mass, no zonation pattern for these beta-thymosins was observed. Remarkable differences were seen regarding the degree of immunoreactivity between the two peptides. In 21 out of 23 cases (91%) Tβ10 reactivity was higher when compared to Tβ4 immunostaining (Figure 3), in one case Tβ10 reactivity was similar to Tβ4 and in one case Tβ4 exceeded Tβ10 reactivity (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overview of the degree of reactivity for Tβ4 and Tβ10 in all 23 liver samples diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma. Tβ4 was present in 7 of the 23 cases (30%), whereas Tβ10 was detected in 22 of the 23 cases (96%).

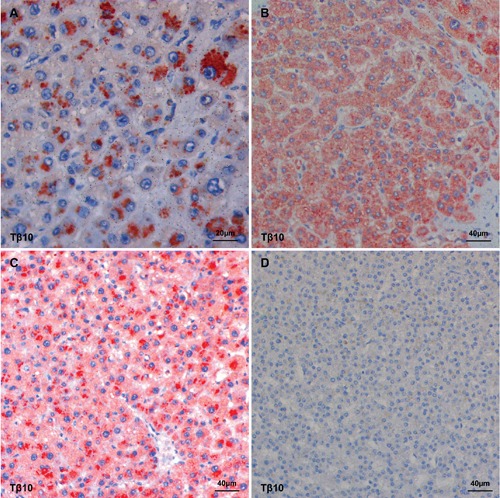

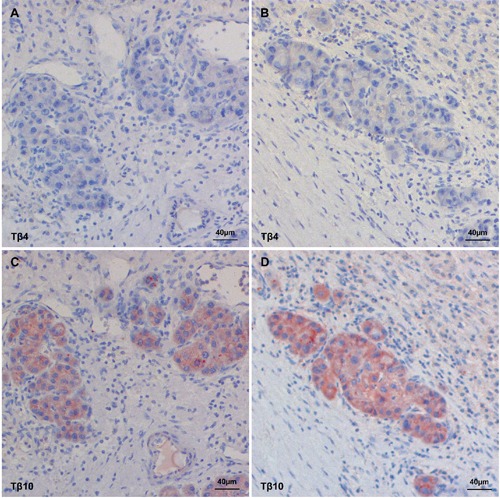

An intriguing finding was represented by the peculiar immunohistochemical pattern observed in case Nº18 were both peptides were highly expressed. In this case, four different clones with a different reactivity pattern and reactivity intensity were observed: a punctuated and granular staining localized in the perinuclear zone (Figure 4A); a homogenous staining reactivity distributed over the entire cytoplasm (Figure 4B); a homogeneous staining in combination with granular reactivity (Figure 4C); absence of reactivity for both peptides in one clone (Figure 4D). In 9 out of 23 cases (39%) immunostaining for Tβ4 and Tβ10 was markedly uneven. In these HCCs, different tumor clones were detected showing a marked variability regarding the intensity of expression of both peptides (Figure 5). No relationship was seen between the degree of Tβ4 and Tβ10 immunostaining and tumor grade in these cases. Analysis of the 5 HCC cases in which multiple samples were obtained, revealed that both Tβ4 and Tβ10 were unevenly expressed over all the samples. In particular in case Nº16 were the degree of reactivity for Tβ4 and Tβ10 ranged from grade 0 up to grade 2, and in case Nº20 from grade 0 up to grade 3. On this basis, in order to avoid mistakes due to sampling variability, all needle biopsies and tissue microarrays were excluded from the present study. When the degree of immunore-activity for Tβ4 and Tβ10 was compared with tumor grade according to Edmondson,18 reactivity for Tβ10 was detected in the entire spectrum of tumor grades (I-IV). On the contrary, Tβ4 reactivity was predominantly seen in grade I and grade II tumors, being absent in vast majority of the poorly differentiated HCCs. The only grade III HCC with Tβ4 immunoreactivity was a relatively small tumor (1.5 cm in diameter) compared to all other grade III tumors (Figure 6). In six cases, in which a complete fibrous capsule was absent, HCC was characterized by infiltrative margins with small tumor nests infiltrating the surrounding liver. When immunohistochemistry for Tβ4 and Tβ10 was applied to these cases, infiltrating tumor cells showed a strong immunoreactivity for Tβ10 (Figure 7C and 7D), in the absence of any significance reactivity for Tβ4 (Figure 7A and 7B).

Figure 4.

Four different tumor clones in the same hepatocellular carcinoma stained with Tβ10 (stained in red). A) A granular staining localized in the perinuclear regions. B) A homogeneous staining diffusely distributed over the entire cytoplasm. C) A homogeneous staining in combination with a granular staining in the perinuclear area. D) No reactivity.

Figure 5.

Two different tumor clones of the same hepatocellular carcinoma stained with Tβ4. A) One clone with red granular Tβ4 reactivity. B) The other clone with no Tβ4 reactivity.

Figure 6.

Degree of immunoreactivity of Tβ4 and Tβ10 compared with the tumor grade according to Edmondson. Tβ4 is mainly present in well differentiated tumors; Tβ10 is present in the entire spectrum of tumor grades.

Figure 7.

Immunoreactivity of Tβ4 and Tβ10 in small tumor nests infiltrating the surrounding liver. A, B) Tβ4 immunostaining is absent in the infiltrating cells. C, D) Tβ10 shows a clear, red, homogeneous reactivity in the infiltrating cells.

Discussion

Several recent studies have identified that beta-thymosins, including Tβ4 and Tβ10, are highly expressed in some cancer cells.6 In particular, Tβ4 has been described to be upregulated in colon cancer.19,20 When Tβ4 expression was analyzed by immunohistochemistry in the whole colon cancer mass, the peptide was mainly localized in tumor cells undergoing epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) at the deep infiltrative margins14 suggesting a major role for Tβ4 in enhancing the migration ability and the metastatic behavior of tumor cells in colon cancer.21 Taken all together, these data indicate Tβ4 expression as a poor prognostic indicator, being associated with poor overall survival in patients affected by colon cancer. On the basis of these data, it has been hypothesized that Tβ4 might represent a feasible therapeutic target for human colorectal cancer.22 Tβ10, the other beta-thymosin highly expressed in human tissues, has been reported to be upregulated in multiple human tumors, including pancreatic cancer,23 melanoma24 and in multiple tumor cell lines including colon cancer, thyroid cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, uterine and esophageal cancer cells.25 In human thyroid carcinoma cells, Tβ10 expression reached the highest levels in anaplastic carcinoma, whereas the peptide was absent in normal thyroid tissue and in thyroid adenoma, indicating immunoreactivity for Tβ10 as a possible tool in the diagnosis of thyroid neoplasias.26

In the present study, we first report that both Tβ4 and Tβ10 are expressed in human HCC cells, adding HCC to the series of human cancers that express these beta-thymosins. Immunostaining for both thymosins was detected in the surrounding liver in all cases analyzed, as well as in the 9 control liver biopsies in which no tumor was detected. This finding confirms previous studies from our group on the high expression of Tβ4 in the adult normal human liver27 and add Tβ10 to the list of beta-thymosins highly expressed in the hepatocytes in adulthood. Interestingly, in this study some differences were found between Tβ4 and Tβ10 regarding the expression pattern and the acinar zones involved in their distribution. Whereas Tβ4 immunostaining was characterized by a granular reactivity, immunoreactivity for Tβ10 showed two staining patterns: a granular reactivity and a homogeneous diffuse cytoplasmic staining. Moreover, whereas a clear zonation was observed for Tβ4 with zone 3 hepatocytes being mainly involved in its expression, reactivity for Tβ10 was less compartmentalized: in particular, the homogeneous immunoreactivity for Tβ10 was detected in periportal hepatocytes (zone 1 of acinus) as well as in periterminal hepatocytes (zone 3 of acinus) (Figure 2A and 2C). Immunoreactivity for both beta-thymosins was high in periterminal hepatocytes (zone 3 of acinus) and highly expressed in the same hepatocytes (Figure 2B and 2D), suggesting a major role of liver cells in beta-thymosin production and, possibly, secretion in blood. The expression pattern, the degree of expression and the frequency of immunoreactivity for these two beta-thymosins in HCCs showed marked differences, that deserve some considerations. Tβ10 was expressed in the vast majority of tumors, being detected in 22 out of 23 cases. Moreover, the degree of immunoreactivity was very high in 6 cases (grade 3) and high in 7 cases (grade 2). On the contrary, reactivity for Tβ4 was detected only in 7 out of 23 cases, being characterized by low levels (grade 1) of immunostaining in 6 out of 7 positive cases. In one case, both thymosins were highly expressed. The expression pattern of Tβ4 and Tβ10 was characterized by a patchy distribution, with some positive tumor clones adjacent to completely negative tumor areas. The variability of immunostaining for both peptides was more evident in the five cases in which multiple tumor samples were studied. Sampling variability was particularly evident in case Nº20, where in one tumor sample immunoreactivity for both beta-thymosins was completely absent, whereas in another sample tumor cells were characterized by very high levels (grade 3) of reactivity for Tβ4 and Tβ10. These findings confirm the previously reported intratumoral sampling variability in HCC for Glypican 3 and for other immunohistochemical markers,28 confirming the heterogeneity of tumor clones and tumor cells within each HCC. Moreover, our data clearly indicate that caution should be taken in the interpretation of immunostaining for Tβ4 and Tβ10 when determined in a small needle biopsy. Due to the variability of immunoreactivity for these beta-thymosins in different tumor clones, the immunostaining for Tβ4 and Tβ10 should not be considered as absolutely representative and reliable of their expression in the whole tumor mass. An interesting finding, regarding the function of beta-thymosin expression in HCC is represented by the high reactivity of tumor cells infiltrating the surrounding liver for Tβ10. This reactivity contrasts with the absence of immunostaining for Tβ4. In a previous study from our group, a major role has been hypothesized for Tβ4 in colon cancer, Tβ4 reactivity being strictly associated with the process of EMT at the deep infiltrative margins of the tumor mass.14 This study confirms the association of beta-thymosins with the infiltrating ability of tumor cells, but shows that each single tumor may utilize different beta-thymosins. Whereas colon cancer cells use, to this end, Tβ4, here we show that HCC cells utilize Tβ10. In conclusion, our preliminary data suggest a role for Tβ4 and Tβ10 in liver carcinogenesis. Further studies are needed in order to shed light on the intimate significance of the expression of these thymosins not only during liver carcinogenesis, but mainly in HCC progression. Moreover, studies comparing serum levels of Tβ4 and Tβ10 with immunoreactivity for both peptides in tumor cells are needed. The higher incidence of Tβ10 expression detected in the vast majority of HCCs and its higher reactivity in small tumor nests infiltrating the surrounding liver indicate a major role for Tβ10 in HCC progression and in its metastatic ability. These data confirm previous hypotheses indicating Tβ10 as a new progression marker for multiple human tumors24 and indicate Tβ10 as a promising marker and a possible novel therapeutic target for liver cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out thank to a grant from “Fondazione Banco di Sardegna”.

References

- 1.Goldstein AL, Slater FD, White A. Preparation assay and partial purification of a thymic lymphocytopoietic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;56:1010-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannappel E. β-Thymosins. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1112:21-37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein AL, Hannappel E, Kleinman HK. Thymosin β4: actin-sequestering protein moonlights to repair injured tissues. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jo JO, Kang YJ, Ock MS, Kleinman HK, Chang HK, Cha HJ. Thymosin ?4 expression in human tissues and in tumors using tissue microarrays. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2011;19:160-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sosne G, Qiu P, Goldstein AL, Wheater M. Biological activities of thymosin beta 4 defined by active sites in short peptide sequences. Faseb J. 2010;24:2144-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu FX, Lin SC, Morrison-Bogorad M, Atkinson MA, Yin HL. Thymosin beta 10 and thymosin beta 4 are both actin monomer sequestering proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993; 268:502-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sribenja S, Li M, Wongkham S, Wongkham C, Yao Q, Chen C. Advances in thymosin β10 research: Differential expression, molecular mechanisms and clinical implications in cancer and other conditions. Canc Invest. 2009;2:1016-1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SH, Son MJ, Oh SH, Rho SB, Park K, Kim YJ, et al. Thymosin β10 inhibits angio-genesis and tumor growth by interfering with Ras function. Cancer Res. 2005;65:137-48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall AK. Thymosin β10 accelerates apoptosis. Cell Mol Biol Res. 1995;41:167-80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nemolato S, Cabras T, Fanari MU, Cau F, Fanni D, Gerosa C. Immunoreactivity of thymosin beta 4 in human foetal and adult genitourinary tract. Eur J Histochem. 2010;54:e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemolato S, Cabras T, Fanari MU, Cau F, Fraschini M, Manconi B, et al. Thymosin beta 4 expression in normal skin, colon mucosa and in tumor infiltrating mast cells. Eur J Histochem. 2010;54:e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nemolato S, Ekstrom J, Cabras T, Gerosa C, Fanni D, Di Felice E, et al. Immunoreactivity for thymosin beta 4 and thymosin beta 10 in the adult rat oro-gastro-intestinal tract. Eur J Histochem. 2013;57:e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faa G, Nemolato S, Cabras T, Fanni F, Gerosa C, Fanari M, et al. Thymosin beta-4 expression reveals intriguing similarities between fetal and cancer cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2012;1269:53-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemolato S, Restivo A, Cabras T, Coni PP, Zorcolo L, Orrù G, et al. Thymosin β4 in colorectal cancer is localized predominantly at the invasion front in tumor cells undergoing epithelial mesenchymal transition. Canc Biol Ther. 2012;13:191-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verghese-Nikolakaki S, Apostolikas N, Livaniou E, Ithakissios DS, Evangelatos GP. Preliminary findings on the expression of thymosin β10 in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1441-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu Y, Wang C, Wang Y, Qiu X, Wang E. Expression of thymosin β10 and its role in non-small cell lung cancer. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:117-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santelli G, Cannada Bartoli P, Giuliano A, Porcellini A, Mineo A, Barone MV, et al. Thymosin β-10 protein synthesis suppression reduces the growth of human thyroid carcinoma cells in semisolid medium. Thyroid. 2002;12:765-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burt AD, Portman BC, Ferrell LD. Tumours and tumour-like lesions of the liver. MacSween’s pathology of the liver. Elsevier; 2012, 792-3 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricci-Vitiani L, Mollinari C, Di Martino S, Biffoni M, Pilozzi E, Pagliuca A. Thymosin β4 targeting impairs tumorigenic activity of colon cancer stem cells. Faseb J. 2010;24:4291-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei-Shu W, Po-Min C, Hung-Liang H, Sy-Yeuan J, Yeu S. Overexpression of the thymosin β4 gene is associated with malignant progression of SW480 colon cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:3297-306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mei-Chuan T, Li-Chaun C, Yi-Chen Y, Cheng-Yu C, Teh-Ying C, Wei-Shu W. Thymosin beta 4 induces colon cancer cell migration and clinical metastasis via enhancing ILK/IQGAP1/Rac1 signal transduction pathway. Cancer Lett. 2011;308:162-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei-Shu W, Hung-Liang H, Mei-Chuan T, Su Y. Thymosin beta-4 from a G-actin binding protein to a malignancy promoter for human colon cancer. Third Annual Symposium on Thymosins in health and disease, Washington, DC, USA: March 14-16201231 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li M, Zhang Y. Thymosin beta 10 is Aberrantly Expressed in Pancreatic Cancer and Induces JNK Activation. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:251-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weterman MAJ, Van Muijen GNP, Ruiter DJ, Bloemers HPJ. Thymosin β-10 expression in melanoma cell lines and melanocytic lesions: a new progression marker for human cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer. 1993;53:278-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santelli G, Califano D, Chiapatta G, Vento MT, Bartoli PC, Zullo F. Thymosin beta-10 gene overexpression is a general event in human carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1999; 155:799-804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiappetta G, Pentimalli F, Monaco M, Fedele M, Pasquinelli R, Pierantoni GM. Thymosin beta-10 gene expression as a possible tool in diagnosis of thyroid neoplasias. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:239-43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nemolato S, Van Eyken P, Cabras T, Cau F, Fanari MU, Fanni D. Expression pattern of thymosin beta 4 in adult human liver. Eur J Histochem. 2011;55:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senes G, Fanni D, Faa G, Cois A, Uccheddu A. Intratumoral sampling variability in hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4019-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]