Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic giant cell tumors are rare, with an incidence of less than 1% of all pancreatic tumors. Osteoclastic giant cell tumor (OGCT) of the pancreas is one of the three types of PGCT, which are now classified as undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

The patient is a 57 year old woman who presented with a 3 week history of epigastric pain and a palpable abdominal mass. Imaging studies revealed an 18 cm × 15 cm soft tissue mass with cystic components which involved the pancreas, stomach and spleen. Exploratory laparotomy with distal pancreatectomy, partial gastrectomy and splenectomy was performed. Histology revealed undifferentiated pancreatic carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells with production of osteoid and glandular elements.

DISCUSSION

OGCT of the pancreas resembles benign-appearing giant cell tumors of bone, and contain osteoclastic-like multinucleated cells and mononuclear cells. OGCTs display a less aggressive course with slow metastasis and lymph node spread compared to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Due to the rarity of the cancer, there is a lack of prospective studies on treatment options. Surgical en-bloc resection is currently considered first line treatment. The role of adjuvant therapy with radiotherapy or chemotherapy has not been established.

CONCLUSION

Pancreatic giant cell tumors are rare pancreatic neoplasms with unique clinical and pathological characteristics. Osteoclastic giant cell tumors are the most favorable sub-type. Surgical en bloc resection is the first line treatment. Long-term follow-up of patients with these tumors is essential to compile a body of literature to help guide treatment.

Keywords: Giant cell, Pancreas, Osteoclastic

Abbreviations: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; cGy, centigray; CT, computerized tomography; GCT, giant cell tumor; MV, megavolts; OGCT, osteoclastic giant cell tumor; PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; PR, pancreatic resection; PGCT, pleomorphic giant cell tumor; RFA, radio frequency ablation; RT, radiotherapy

1. Introduction

Pancreatic neoplasms are relatively common gastrointestinal malignancies, with the most common type being adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. However there are several types of pancreatic cancer that are much less common, including pancreatic giant cell tumors (PGCT) which are rare non-endocrine tumors of the pancreas with an incidence of less than 1% of all pancreatic tumors.1 They were first described in 1954 by Sommers and Meissner.2 There are three types of pancreatic giant cell tumors: osteoclastic, pleomorphic, and mixed; however since 2010, the World Health Organization has grouped them together as undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast- like giant cells.3,4 The osteoclastic variant has a better prognosis than the other two subtypes, as well as pancreatic adenocarcinoma.5 Giant cell tumors are also seen in other organs including the breast, thyroid, parotid, colon, skin, orbit, kidney, heart and soft tissue.1,6

PGCT usually affects patients in the 6th to 7th decade of life, with an equal male to female ratio.6 PGCT mostly involve the body and tail of the pancreas, unlike pancreatic adenocarcinoma which mainly involves the head.6,7 Common clinical presentations of PGCT are nonspecific abdominal pain, distension and a palpable mass, whereas jaundice is the most common presentation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PGCT measures around 5–6 cm at presentation in 60–80% of cases.3 We describe the second largest PGCT reported to date, presenting in an otherwise healthy middle-aged woman.

2. Presentation of case

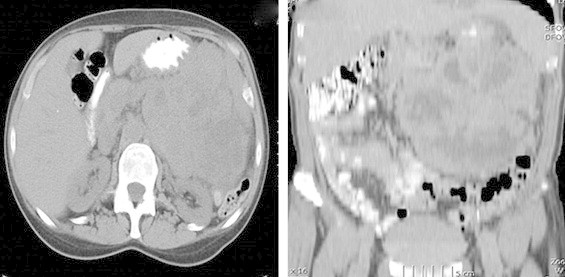

A 56-year old previously healthy Caucasian woman who worked as a sales assistant at a clothing store presented to her primary care doctor for vague epigastric abdominal pain of 3 weeks duration, a palpable abdominal mass, bilateral leg swelling and anemia with hemoglobin of 7.3 g/dl. Her evaluation included an ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvis which showed a 16 cm × 14 cm mass that was largely solid with mixed echotexture and small cystic areas in the center of the abdomen, with an adjacent mass 11 cm × 9 cm at the left adnexa. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a single 18 cm × 15 cm complex soft tissue mass with multiple fluid areas and an area of necrosis. The mass extended from the left iliac fossa to the mid spleen (Figs. 1 and 2). The tail of the pancreas was effaced and obscured by the mass. There were enlarged lymph nodes 1.5 cm × 1 cm in size to the left of the aorta and at the L2 and L3 level. The patient was referred to a gynecologic oncologist for possible left ovarian cancer and scheduled for total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Fig. 1.

CT scan of abdomen and pelvis showing soft tissue mass with multiple fluid areas and areas of necrosis, with poor definition of the tail of the pancreas. It extends from the tail of pancreas to mid spleen and to the level of left iliac crest.

Fig. 2.

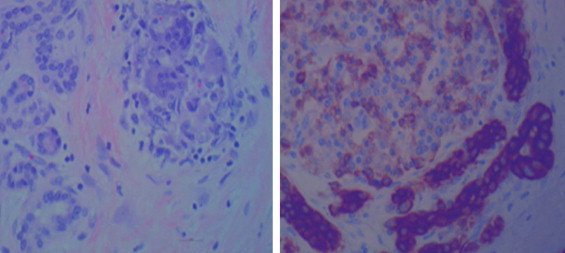

Images were taken at 400× with 75 gold scale bars. On left Hematoxylin and eosin stains images; on right are CK AE1/AE3 immunohistochemical stains. They show cancersous glands invested by inflammatory cells including osteoclast-like giant cells.

At laparatomy, a large complex mass was found invading into the stomach, pancreas, mesentery and meso-colon. The general surgical service was consulted and an oncologic resection of the mass performed in concert with the gynecologic oncologists. The mass was smooth-walled with a pseudo-capsule effect and was able to be carefully dissected from the adherent structures using a combination of sharp dissection, electrocautery and harmonic scalpel. The actual site of origin of the tumor was unable to be determined during this operation since it invaded several structures (pancreas, spleen and stomach) and disparate areas of the retroperitoneum and mesentery. The patient underwent stapled distal pancreatectomy, partial gastrectomy, splenectomy and total excision of the mass. Grossly the mass consisted of a multiloculated cystic lesion measuring 24 cm × 16 cm × 10 cm, with a total weight of 2.5 kg. The patient's CA 19-9 was found to be elevated at 392 units/mL one week after surgery.

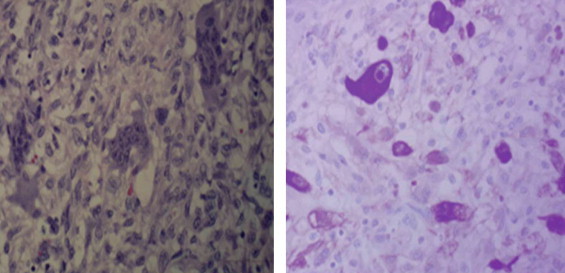

Histologic examination revealed undifferentiated pancreatic metaplastic carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells with production of osteoid and with glandular elements (Figs. 2 and 3). The hematoxylin and eosin stain images and CKAE1/AE3 immunohistochemical stains showed glands invested by inflammatory cells including osteoclast-like giant cells. Initial sampling revealed only the inflammatory cells with osteoclast-like giant cells, possibly consistent with sarcoma. After extensive sampling, carcinomatous foci were identified whose nature was elucidated immunohistochemically. The presence of glands excluded sarcoma. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for vementin and negative for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), consistent with mesenchymal phenotype. CD34 staining demonstrated lymphovascular spread. The mucinous epithelial cells stained for EMA and keratin. The pancreatic specimen had an initial positive margin.

Fig. 3.

Diffuse region of inflammatory cells including osteoclast clike giant cells with, on right, a single large cancer cell. Osteoclast like giant cells didn’t stain with CK AE1/AE3.

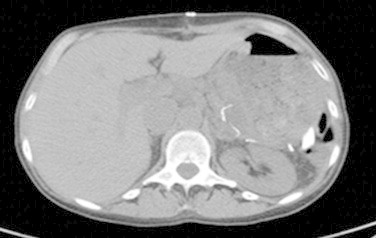

Her post-operative course was uneventful and she was discharged home on day 4, tolerating a regular diet, ambulating and with pain controlled on minimal oral hydrocodone and acetaminophen. A post-operative CT was performed to complete the evaluation for metastatic disease, since the pre-operative CT did not include the chest and was a non-contrast study (Fig. 4). Due to the positive pancreatic margin she underwent surgical re-exploration on day 9, with clearing of the positive pancreatic margin confirmed by frozen section analysis. Once again she did very well and was discharged home three days after this final operation. She underwent a short course of radiation therapy to the area of previous tumor infiltration which had been marked by surgical clips intra-operatively. She was initially treated with a dose of 3060 cGy in 17 fractions to her tumor bed using intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) technique with the 6 MV unit. This was followed by subsequent boost with a dose of 2880 cGy in 16 fractions, also using IMRT technique with the 6 MV unit. The total dose was 5940 cGy in 33 fractions. The patient tolerated radiation therapy very well without complications and remains well 6 months post-operatively. A follow-up CT scan of abdomen and pelvis is planned one year from initial surgery.

Fig. 4.

Post operative CT of abdomen and pelvis showing post surgical changes with distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy and with fluid collection around the pancreas.

3. Discussion

Osteoclastic giant cell tumors (OGCT) resemble benign-appearing giant cell tumors of bone, and contain osteoclast-like multinucleated cells and mononuclear cells. The histogenesis of OGCT is controversial, with a suggestion of both epithelial and mesenchymal origin. The positive immunohistochemical staining for CEA and keratin favor epithelial derivation, whereas the positivity for CD68 and vimentin and negativity of cytokeratin favor mesenchymal origin. OGCT have a less aggressive course with slow metastasis and lymph node spread with a better prognosis compared to pleomorphic giant cell tumors and adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. The interval to death or disease progression ranges from 4 months to 10 years from initial diagnosis.7

In contrast, pleomorphic giant cell tumor of the pancreas is a highly anaplastic malignancy with pleomorphic mononuclear and multinucleated giant cells. The positivity for cytokeratin and negativity for CD68 and vementin favors their epithelial origin. This tumor follows an aggressive course with early metastasis and poor prognosis similar or worse to adenocarcinoma of pancreas. Because of this significant difference in clinical behavior and prognosis, it is important to identify and distinguish between the subtypes of PGCT. Unfortunately, due to the rarity of this neoplasm, there is a lack of large scale studies or individual personal experience with this tumor. Elevation of tumor markers such as CEA and CA19-9 are less frequent in PGCT than adenocarcinomas8,9 thus rendering them less useful for diagnosis or monitoring.

The paucity of evidence upon which to base treatment decisions leads to difficulty in determining the optimal multi-disciplinary approach for each patient. In general, surgical en-bloc resection is considered the first line of treatment7,10 while the role of adjuvant therapy is unclear. Considering the radio-sensitivity of giant cell tumors of the bone,11 there is a theoretical benefit of abdominal radiotherapy for PGCT as well, and this was the basis for our decision to proceed with radiotherapy despite an apparent complete surgical resection. Given the epithelial origin of the mononuclear neoplastic cells, it may be reasonable to consider agents such as gemcitabine in cases of disseminated disease or incomplete resection.

This is the second largest PGCT ever reported, with the largest being 24.5 cm.12 The late presentation, minimal symptomatology and rapid successful recovery of this patient illustrate that despite the large size of the OGCT, she was physiologically not severely impaired, in contrast to what would be expected of a patient with an adenocarcinoma of the pancreas of comparable size – a situation that almost never arises, due to its much more aggressive nature and tendency to metastasize. This strengthens the argument for aggressive surgical therapy as first line treatment, since OGCT appears to be primarily a locally invasive tumor, as opposed to one with a high tendency to metastatic disease. A summary of the characteristics and treatment of PGCT that have been described in the recent literature, from 2002 to 2012 is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of pancreatic giant cell tumors described between 2002 and 2012, showing treatment and outcome.

| Year of publication | Author | Number of cases | Type of pancreatic giant cell cancer | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200213 | Shiozawa | 32 | Undifferentiated osteoclast like giant cell | Pancreatic Resection | Mean survival of 20.4 months |

| 20049 | Zou | 19 | GCT | Inoperable-14, PD-2, Pancreatic resection-3 | Mean survival of 4 months |

| 200414 | Loya | 1 | Mixed | PD | Alive at 3 years |

| 200415 | Osaka | 1 | OGCT | DP + S + TG | Alive at 3 years |

| 200516 | Ezenekwe | 1 | Mixed | Inoperable | |

| 20063 | Lukas | 2 | Inoperable | ||

| 200617 | Sautot-Vial | 1 | OGCT | PD | Overall 26 months of survival |

| 200618 | Tezuka | 1 | Intraductal OGCT | PD | Alive without recurrence at 22 months |

| 200619 | Bauditz | 1 | Mixed | Chemotherapy | Continued CT at 13 months |

| 200620 | Janes | 1 | OGCT | Palliation | Died at 7 months |

| 200821 | Layfield | 6 | PGCT-5, OGCT-1 | PD-1 Unresectable-3 Metastasis-2 |

Alive at 3 months Died at 3 months Lost follow up |

| 200922 | Moore | 5 | PGCT-3, OGCT-1 Mixed-1 |

Palliation-3, PD + hepatic segmentectomy + RFA + RT PD + chemotherapy |

Died at mean of 12.3 weeks-3 Alive at 18 months-1 Alive at 13 months-1 after resection |

| 200923 | Marosh | 1 | Undifferentiated GCT | PD + lymph node resection | Died 12 months after resection |

| 20091 | Burkadze | 1 | OGCT | Pancreatic resection | Free of disease after 4 years |

| 201024 | Rauramaa | 1 | OGCT | PD | Free of disease after 1.5 years of resection |

| 20102 | Athanasios | 1 | Pleomorphic GCT | En-bloc resection | Recurrence at 4 months |

| 20105 | Singhal | 1 | OGCT | Pancreatic resection | – |

| 20116 | Rustagi | 1 | PGCT | PD | No recurrence after 20 months |

| 201125 | Wada | 1 | OGCT | Pancreatic resection | Died after 4 months |

| 201126 | Schaffner | 1 | OGCT | – | Pulmonary metastasis |

| 201227 | Sivanandham | 1 | OGCT | – | – |

4. Conclusion

Pancreatic giant cell tumors are rare pancreatic neoplasms with unique clinical and pathological characteristics. Osteoclastic giant cell tumors are the most favorable sub-type, and en-bloc resection is the first line of treatment. The roles of chemotherapy and radiotherapy either as adjuvant or neoadjuvant agents have not been clearly established. Long term follow-up of patients with these rare tumors is essential in order to compile a body of literature to help guide treatment, since the rarity of this tumor renders prospective studies unlikely.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

None.

Author contributions

Each author contributed to writing and editing the case report.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Wudneh M. Temesgen, Email: wudneh.temesgen@ttuhs.edu.

Mitchell Wachtel, Email: mitchel.wachtel@ttuhsc.edu.

Sharmila Dissanaike, Email: Sharmila.dissanaike@ttuhsc.edu.

References

- 1.Burkadze G., Turashvili G. A case of osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas associated with borderline mucinous cystic neoplasm. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15(March (1)):129–131. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Athanasios P., Alexandros P., Nicholas B., Dimitrios K., Kostantinos B., Antonio M. Pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma of the pancreas with hepatic metastases -- initially presenting as a benign serous cystadenoma: a case report and review of the literature. HPB Surg. 2010;2010:627360. doi: 10.1155/2010/627360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukas Z., Dvorak K., Kroupova I., Valaskova I., Habanec B. Immunohistochemical and genetic analysis of osteoclastic giant cell tumor of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2006;32(April (3)):325–329. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000202951.10612.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannan R., Khanna M., Bhasin T.S., Misra V., Singh P.A. Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas: a discussion of rare entity in comparison with pleomorphic giant cell tumor of the pancreas. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53(October–December (4)):867–868. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.72016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhal A., Shrago S.S., Li S.F., Huang Y., Kohli V. Giant cell tumor of the pancreas: a pathological diagnosis with poor prognosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9(August (4)):433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rustagi T., Rampurwala M., Rai M., Golioto M. Recurrent acute pancreatitis and persistent hyperamylasemia as a presentation of pancreatic osteoclastic giant cell tumor: an unusual presentation of a rare tumor. Pancreatology. 2011;11(1):12–15. doi: 10.1159/000323210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leighton C.C., Shum D.T. Osteoclastic giant cell tumor of the pancreas: case report and literature review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24(February (1)):77–80. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200102000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nojima T., Nakamura F., Ishikura M., Inoue K., Nagashima K., Kato H. Pleomorphic carcinoma of the pancreas with osteoclast-like giant cells. Int J Pancreatol. 1993;14(December (3)):275–281. doi: 10.1007/BF02784937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou X.P., Yu Z.L., Li Z.S., Zhou G.Z. Clinicopathological features of giant cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2004;3(May (2)):300–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore J.C., Bentz J.S., Hilden K., Adler D.G. Osteoclastic and pleomorphic giant cell tumors of the pancreas: a review of clinical, endoscopic, and pathologic features. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2(January (1)):15–19. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi W., Indelicato D.J., Reith J., Smith K.B., Morris C.G., Scarborough M.T. Radiotherapy in the management of giant cell tumor of bone. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36(October (5)):505–508. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182568fb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jotsuka T., Hirota M., Tomioka T., Ohshima H., Katsumori T., Miyanari N. Giant cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;18(May (4)):415–417. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiozawa M., Imada T., Ishiwa N., Rino Y., Hasuo K., Takanashi Y. Osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas. Int J Clin Oncol. 2002;7(December (6)):376–380. doi: 10.1007/s101470200059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loya A.C., Ratnakar K.S., Shastry R.A. Combined osteoclastic giant cell and pleomorphic giant cell tumor of the pancreas: a rarity. An immunohistochemical analysis and review of the literature. JOP. 2004;5(July (4)):220–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osaka H., Yashiro M., Nishino H., Nakata B., Ohira M., Hirakawa K. A case of osteoclast-type giant cell tumor of the pancreas with high-frequency microsatellite instability. Pancreas. 2004;29(October (3)):239–241. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200410000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezenekwe A.M., Collins B.T., Ponder T.B. Mixed osteoclastic/pleomorphic giant cell tumor of the pancreas: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49(September–October (5)):549–553. doi: 10.1159/000326204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sautot-Vial N., Rahili A., Karimdjee-Soihili B., Benizri E., Avallone S., Benchimol D. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic, osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(June (6)):1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tezuka K., Yamakawa M., Jingu A., Ikeda Y., Kimura W. An unusual case of undifferentiated carcinoma in situ with osteoclast-like giant cells of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2006;33(October (3)):304–310. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000235303.11734.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauditz J., Rudolph B., Wermke W. Osteoclast-like giant cell tumors of the pancreas and liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(December (48)):7878–7883. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janes S., Cid J., Kaye P., Doran J. Pancreatic osteoclastoma: immunohistochemical evidence of a reactive histiomonocytic origin. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(March (3)):198–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layfield L.J., Bentz J. Giant-cell containing neoplasms of the pancreas: an aspiration cytology study. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36(April (4)):238–244. doi: 10.1002/dc.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore J.C., Hilden K., Bentz J.S., Pearson R.K., Adler D.G. Osteoclastic and pleomorphic giant cell tumors of the pancreas diagnosed via EUS-guided FNA: unique clinical, endoscopic, and pathologic findings in a series of 5 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(January (1)):162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manduch M., Dexter D.F., Jalink D.W., Vanner S.J., Hurlbut D.J. Undifferentiated pancreatic carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells: report of a case with osteochondroid differentiation. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205(5):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rauramaa T., Pulkkinen J., Miettinen P., Kainulainen S., Seppa A., Karja V. Case report: osteoclast-like giant cell tumour of the pancreas without epithelial differentiation. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(April (4)):376–377. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.069260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wada T., Itano O., Oshima G., Chiba N., Ishikawa H., Koyama Y. A male case of an undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells originating in an indeterminate mucin-producing cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. A case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:100. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaffner T.J., Richmond B.K. Osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas with subsequent pulmonary metastases. Am Surg. 2011;77(December (12)):E275–E277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sivanandham S., Subashchandrabose P., Muthusamy K.R. FNA diagnosis of osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas. J Cytol. 2012;29(October (4)):270–272. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.103951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]