Abstract

Background

Breast papillomas often are diagnosed with core needle biopsy (CNB). Most studies support excision for atypical papillomas, because as many as one half will be upgraded to malignancy on final pathology. The literature is less clear on the management of papillomas without atypia on CNB. Our goal was to determine factors associated with pathology upgrade on excision.

Methods

Our pathology database was searched for breast papillomas diagnosed by CNB during the past 10 years. We identified 277 charts and excluded lesions associated with atypia or malignancy on CNB. Two groups were identified: papillomas that were surgically excised (group 1) and those that were not (group 2). Charts were reviewed for the subsequent diagnosis of cancer or high-risk lesions. Appropriate statistical tests were used to analyze the data.

Results

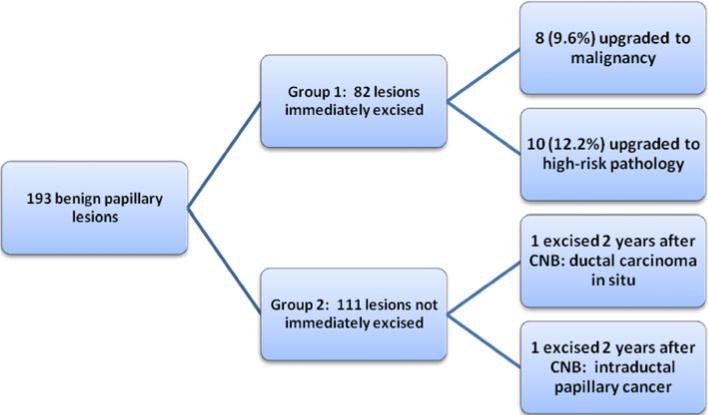

A total of 193 papillomas were identified. Eighty-two lesions were excised (42%). Caucasian women were more likely to undergo excision (p = 0.03). Twelve percent of excised lesions were upgraded to malignancy. Increasing age was a predictor of upgrading, but this was not significant. Clinical presentation, lesion location, biopsy technique, and breast cancer history were not associated with pathology upgrade. Two lesions in group 2 ultimately required excision due to enlargement, and both were upgraded to malignancy.

Conclusions

Twenty-four percent of papillomas diagnosed on CNB have upgraded pathology on excision—half to malignancy. All of the cancers diagnosed were stage 0 or I. For patients in whom excision was not performed, 2 of 111 papillomas were later excised and upgraded to malignancy.

Up to 5% of breast lesions that undergo biopsy are diagnosed as papillomas.1 A papilloma consists of a fibrovascular core with frond-like arborization that extends into the mammary duct lumen. The epithelium covering a benign papilloma has two components: a basal myoepithelium, one cell layer thick, and a covering of proliferative epithelium. The epithelium may undergo apocrine metaplasia, hyperplasia, or may develop atypia.2 An incomplete basal myoepithelium is diagnostic of malignancy in a papilloma.3

Papillomas may be located centrally or peripherally within the breast and may occur singly or in large numbers. Central papillomas are more likely to be single and to present with bloody nipple discharge.4 Multiple lesions are more often seen in younger women than are solitary papillomas and are more likely to be asymptomatic, bilateral, and to recur after resection.5 Multiple papillomas also are more likely to be associated with malignancy, but both solitary and multiple papillomas have been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.6–9

Papillomas with atypia are associated with increased rates of malignancy.7,9 Atypia within a papilloma may be patchy and tends to be located at the periphery of the lesion.7,10 Not infrequently, atypia is found nearby but not within the papilloma. Because of these features, and because of the heterogeneous nature of papillomas, diagnosing atypia and/or malignancy within a papilloma on percutaneous biopsy may be difficult.11

Papillary carcinoma is uncommon, accounting for <2% of breast cancers.12 It is most likely to be associated with papillomas with significant atypia.13 In contrast to other ductal carcinomas, papillary cancer is less likely to metastasize to lymph nodes and overall has a better prognosis.10

The literature reports a consensus to excise any papillomas with atypia found on percutaneous core needle biopsy (CNB) due to an up to 67% likelihood of finding malignancy at excision.3,13–15 The data are less consistent regarding the likelihood of finding malignant or high-risk pathology when the percutaneous biopsy shows a completely benign papilloma.1,6,14,16–18 The purpose of our study was to determine how often benign papillomas at our institution are upgraded on excisional pathology to a high-risk lesion or malignancy and to determine patient factors associated with pathology upgrading.

METHODS

Institutional review board approval was obtained before commencement of this study. Patient consent was not required. The prospectively maintained pathology database at Barnes-Jewish Hospital/Washington University was searched using the terms “breast,” “papilloma,” “core,” and “needle” to find all breast papillomas diagnosed by CNB from January 1, 1999 to July 1, 2009. Stereotactic and MR-guided biopsies were performed with a 9-gauge Suros vacuum-assisted biopsy device (Suros Surgical Systems, Inc., Indianapolis, IN). Ultrasound- and palpation-guided CNBs were performed using a spring-loaded 14-gauge biopsy device.

We identified 277 records with this diagnosis. Charts were reviewed and any lesions associated with atypia or malignancy at CNB were excluded. Papillomas associated with sclerosis, “complex sclerosing lesions,” and “radial scars” were included in the analysis. The total cohort included 187 patients with 193 papillomas. Two groups were identified: papillomas that were surgically excised after CNB (group 1) and those that were not (group 2).

High-risk pathology was defined as atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH), and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Malignant pathology was defined as invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and papillary carcinoma.

Patient demographics, mode of presentation, radiology findings, biopsy method, core needle and excisional biopsy pathologies, and outcomes were recorded in a single spreadsheet (Excel; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Lesion size was obtained from pathology or radiology reports as appropriate. Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, and Jonckheere-Terpstra test were used for statistical analysis as appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using a statistical package SAS® (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). P values were calculated based on one observation per patient, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. Outcomes of interest included upgrading of benign papillomas to high-risk or malignant pathology at excision and subsequent development of malignancy in papillomas that were not initially excised.

RESULTS

A total of 193 benign papillary lesions were identified in 187 women. The median age of all patients was 57 (range, 28–88) years. All were diagnosed by CNB using stereo-tactic (n = 88), ultrasound (n = 102), palpation (n = 1), or magnetic resonance (MR) guidance (n = 2). Follow-up beyond the initial percutaneous biopsy was available for 117 of the lesions, with a median length of follow-up of 37 (range, 4–125) months (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and characteristics of 193 papillomas diagnosed on core needle biopsy that were immediately excised (group 1) or not excised (group 2)

| Variable | Group 1 (n = 82) | Group 2 (n = 111) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (year) | 56 (32–82) | 57 (28–88) | 0.94 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 48 (58.5) | 48 (43.2) | 0.03 |

| African American | 28 (34.1) | 60 (54.1) | |

| Other | 6 (7.3) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Mammographic appearance | |||

| Calcifications | 17 (20.7) | 55 (49.5) | <0.0001 |

| Mass/density/asymmetry | 55 (67.1) | 47 (42.3) | |

| Othera | 10 (12.2) | 9 (8.1) | |

| Biopsy technique | |||

| Stereotactic | 22 (26.8) | 66 (59.5) | <0.0001 |

| Ultrasound-guided | 57 (69.5) | 45 (40.5) | |

| MRI-guided | 2 (2.4) | 0 | |

| Palpation-guided | 1 (1.2) | 0 | |

| Median lesion size (mm) | 10 (4–30) | 10 (5–80) | 0.75 |

Data are numbers with percentages or ranges in parentheses unless otherwise indicated

Not visible on mammogram and/or incidental finding on other imaging as part of breast cancer workup

Eighty-two papillomas underwent surgical excision subsequent to percutaneous biopsy (group 1). Excision was more frequently performed later during the study period, with 50% of the lesions diagnosed from 2005–2009 being excised versus only 29% of the lesions diagnosed from 1999–2004. Excision was explicitly recommended by radiology for 25 of the 82 lesions in group 1, most frequently based on the risk of upgrading or undersampling per published literature. Only one lesion was excised due to pathology–radiology discordance. Strict criteria were not used to determine discordance or need for excision; excision was recommended based on the radiologist's interpretation. One lesion was excised per the recommendation of pathology, and the remainder were excised for unknown reasons. The median age of group 1 was 56 (range, 32–82) years. Follow-up beyond the initial percutaneous biopsy was available for 53 lesions in group 1, and the median follow-up was 24 (range, 4–84) months. The median lesion size was 10 (range, 4–30) mm. Caucasian women were more likely to undergo papilloma excision (p = 0.03). Lesions appearing as a mass on mammogram were more likely to be excised than lesions presenting as microcalcifications (p < 0.0001). Papillomas biopsied with ultrasound-guidance were more frequently excised than lesions biopsied stereotactically (p < 0.0001). Papillomas presenting with nipple discharge were uniformly excised; only one of these was associated with bloody nipple discharge. Cytology was not performed on the discharge for any of these cases.

Group 2 consisted of 111 papillary lesions that did not undergo excision after CNB. The median age of group 2 (57 years) and the median size of the lesion (10 mm) were not significantly different than group 1. Follow-up was available for 63 lesions in group 2, and the median follow-up was 51 (range, 4–125) months. As observed in group 1, African American women were significantly less likely to undergo surgical excision (p = 0.03). Group 2 lesions more frequently appeared as mammographic microcalcifications than as masses (p < 0.0001), and underwent stereotactic biopsy (p < 0.0001).

Eighteen group 1 lesions were upgraded at excisional biopsy from benign papillary lesions to malignant (n = 8, 9.8%) or high-risk lesions (n = 10, 12.2%). Of the ten lesions upgraded to high-risk pathology, six patients were upgraded to ADH, two to ALH, and two to LCIS. Of the eight patients with malignant pathology, two were upgraded to IDC, five to DCIS, and one to papillary carcinoma. All invasive cancers were T1. The two invasive cancers were both estrogen receptor (ER)- and progesterone receptor (PR)-positive and Her-2neu-negative. The invasive papillary carcinoma had unknown receptor status. Of the DCIS, three were ER/PR-positive, one was ER/PR-negative, and one had unknown receptor status. One invasive cancer was associated with a micrometastatic focus of nodal disease; the other malignancies were node-negative.

Two additional lesions from group 2 ultimately underwent delayed surgical excision for alterations in mammographic appearance. One underwent repeat ultrasound-guided CNB 20 months after the initial percutaneous biopsy; pathology showed an atypical papillary lesion. The lesion was then excised and final pathology revealed DCIS. The second lesion was excised 22 months after the initial stereotactic biopsy and final pathology revealed an intraductal papillary carcinoma. Including these 2 lesions, 84 benign papillary lesions were surgically excised and 20 were upgraded at excisional pathology for an upgrade rate of 23.8%. Figure 1 summarizes the upgraded lesions in our series.

FIG. 1.

Outcomes for 193 papillary lesions diagnosed on core needle biopsy (CNB), which were excised (group 1) or not excised (group 2). Two patients in group 2 underwent delayed excision

These 20 upgraded lesions were compared with the 64 lesions whose excision pathology was not upgraded. Patients with upgraded papillomas were more likely to be postmenopausal, but this was not statistically significant. Race, lesion palpability, lesion location, mammographic appearance, biopsy technique, and nipple discharge were not significantly related to the likelihood of pathology upgrade. Breast cancer history and the presence of a concurrent breast cancer separate from the papilloma were not associated with pathology upgrading. Table 2 summarizes our comparison of these two groups.

TABLE 2.

Patient demographics and characteristics for 84 papillomas surgically excised following core needle biopsy according to presence or absence of upgraded pathology

| Variable | Pathology upgradeda (n = 20) | Pathology not upgraded (n = 64) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age (year) | |||

| Premenopausal (<52) | 4 (19) | 28 (44) | 0.11 |

| Postmenopausal (≥52) | 16 (80) | 36 (56) | |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 13 (62) | 35 (55) | 0.92 |

| African American | 6 (30) | 24 (38) | |

| Other | 1 (5) | 5 (8) | |

| Biopsy technique | |||

| Stereotactic, vacuum-assisted | 6 (29) | 16 (25) | 0.99 |

| Ultrasound-guided | 14 (70) | 44 (69) | |

| Other | 0 | 4 (6) | |

| Mammographic appearance | |||

| Calcifications | 5 (24) | 11 (17) | 0.33 |

| Mass/density/asymmetry | 9 (45) | 33 (52) | |

| Not visible | 6 (29) | 20 (31) | |

| Palpability | |||

| Palpable | 6 (29) | 15 (23) | 0.77 |

| Not palpable | 14 (70) | 49 (77) | |

| Location | |||

| Central | 5 (24) | 10 (16) | 0.51 |

| Peripheral | 15 (71) | 53 (83) | |

| Other | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| Nipple discharge | |||

| Present | 2 (10) | 3 (5) | 0.25 |

| Absent | 18 (90) | 61 (95) | |

| Prior cancer history | |||

| Prior cancer | 1 (5) | 4 (6) | 0.99 |

| No prior cancer | 19 (95) | 60 (94) | |

| Concurrent cancer | |||

| Concurrent cancer | 3 (15) | 9 (14) | 0.99 |

| No concurrent cancer | 17 (85) | 55 (86) |

Data are numbers with percentages in parentheses unless otherwise indicated

For two of these lesions, pathology was upgraded at excisions performed 2 years after the needle core biopsy

DISCUSSION

Papillary lesions diagnosed on CNB present a difficult clinical and diagnostic problem. Because papillomas can be heterogeneous, any atypia or malignancy may be easily missed on a percutaneous biopsy.7,11 For this reason, surgical excision of even benign papillary lesions often has been recommended to rule out any missed malignancy.19,20 Various studies have attempted to identify factors predictive of pathology upgrading to identify which patients might be able to avoid surgical excision, but results have been inconsistent. Older age, larger lesion size, multiple lesions, presence of nipple discharge, and microcalcifications on mammography have all been associated with a higher risk of malignancy.6,16,21–26 Although postmenopausal women in our study were more likely to have upgraded pathology at excision, this was not statistically significant.

In contrast to the above-mentioned studies, Jaffer et al. recently reported on a series of 200 papillary lesions diagnosed by CNB and found that lesion size, biopsy device size, lesion location, palpability, and the presence of nipple discharge did not correlate with pathology upgrading at excision.11 In a smaller series, Ashkenazi et al. also found that lesion size, palpability, imaging Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) status, and breast cancer risk factors did not correlate with pathology upgrading.21 Several other studies have failed to show that radiologic features can predict malignancy in papillary lesions.19,27,28 Our results are consistent with those of Jaffer et al. and Ashkenazi et al. We found no statistically significant relationship between patient age, biopsy device size, lesion location, symptomatology, mammographic appearance, or breast cancer to the likelihood of pathology upgrading.

There were no clinical differences between the excised group and the nonexcised group of papillomas. The malignancies that were diagnosed on excision in our series were early-stage, and the majority were hormone receptor-positive and therefore have a favorable prognosis. Additionally, the two malignancies that were not immediately excised but were initially followed radiographically were noninvasive and therefore delayed excision likely did not affect overall clinical outcome. However, because almost a quarter of benign papillary lesions in our series were upgraded to high-risk or malignant pathology, and because we were unable to identify any obvious features predictive of pathology upgrading, we would recommend continued surgical excision of these lesions, which would allow early treatment and intervention. Observation of papillary lesions would likely underdiagnose malignancy and undertreat high-risk pathology. Women known to have high-risk lesions, such as ADH, ALH, and LCIS, may be screened more intensely and may even receive chemoprophylaxis. If excision is not performed due to patient factors or preference, then short-term imaging follow-up (i.e., 6 months) would be reasonable, and any change in radiographic appearance should prompt excision.

Vacuum-assisted percutaneous biopsy, because of the larger tissue sample size, may miss fewer atypical or malignant lesions than simple CNB and may improve the accuracy of percutaneous biopsy.18,29,30 Several authors have even suggested large-volume, vacuum-assisted, percutaneous biopsy as a possible alternative to surgical excision.31,32 However, papillary lesions diagnosed by vacuum-assisted biopsy in our series were not upgraded significantly less than lesions diagnosed by smaller-gauge CNB.

Our study has several limitations. First, we have limited follow-up data on our patient cohort. Second, papillary lesions are not common and accruing a large cohort is difficult. Third, it is a retrospective study, and there is likely some selection bias in those patients who underwent surgical excision. Additionally, is unclear why certain lesions were recommended for excision and others were not. We did note that many group 1 lesions were recommended for surgical excision by the radiologist performing the image-guided biopsy, but only one of these lesions was excised specifically due to pathology–radiology discordance (and this lesion was upgraded). Many of the patients in group 2 were likely never seen by a surgeon after their percutaneous biopsies. Excision was explicitly not recommended by radiology for 72 of these 111 lesions. Two patients failed any radiologic or surgical follow-up, and two patients saw surgeons who did not recommend excision. Nineteen lesions were not excised due to other patient factors, and 16 were not excised for unknown reasons. Finally, benign papillomas associated with complex sclerotic lesions and radial scars were included in our analysis, but we acknowledge that excision of these latter pathologies often is recommended independent of an associated papilloma because of their own risk of pathology upgrading at excision. Three of the papillomas upgraded on excision pathology in our series had sclerosis or sclerotic change seen on CNB: one was upgraded to ADH, one to ALH, and one to DCIS. However, the decision to excise was based on the finding of a papilloma, regardless of the presence of sclerosis. There were 52 papillomas associated with sclerosis in our total cohort: 22 of the 82 lesions in group 1, and 30 of the 111 lesions in group 2. Because only three upgraded lesions were associated with sclerosis, a smaller fraction compared to the total cohort, it is unlikely that any sclerotic change played a significant role in the pathology upgrading.

Despite these limitations, the current study represents one of the largest reported studies of benign papillomas diagnosed on CNB. Because a clear consensus does not yet exist regarding the management of benign papillomas, a large-volume, prospective trial would be invaluable. In the absence of prospective data, and until we can consistently identify risk factors for pathology upgrade, we recommend excision of all benign papillomas diagnosed on CNB due to the high rate of upgrade.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, for the use of the Biostatistics Core. The Core is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA91842 to the Siteman Cancer Center.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE We have no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosen EL, Bentley RC, Baker JA, et al. Imaging-guided core needle biopsy of papillary lesions of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1185–92. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.5.1791185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacGrogan G, Moinfar F, Raju U. Intraductal papillary neoplasms. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2003. pp. 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sydnor MK, Wilson JD, Hijaz TA, Massey HD, Shaw de Paredes ES. Underestimation of the presence of breast carcinoma in papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core-needle biopsy. Radiology. 2007;242:58–62. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2421031988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabioglu N, Hunt KK, Singletary SE, et al. Surgical decision making and factors determining a diagnosis of breast carcinoma in women presenting with nipple discharge. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:354–64. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01606-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardenosa G, Eklund GW. Benign papillary neoplasms of the breast: mammographic findings. Radiology. 1991;181:751–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.3.1947092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gendler LS, Feldman SM, Balassanian R, et al. Association of breast cancer with papillary lesions identified at percutaneous image-guided breast biopsy. Am J Surg. 2004;188:365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page DL, Salhany KE, Jensen RA, Dupont WD. Subsequent breast carcinoma risk after biopsy with atypia in a breast papilloma. Cancer. 1996;78:258–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960715)78:2<258::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutman H, Schachter J, Wasserberg N, Shechtman I, Greiff F. Are solitary breast papillomas entirely benign? Arch Surg. 2003;138:1330–3. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.12.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupont WD, Page DL. Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:146–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muttarak M, Lerttumnongtum P, Chaiwun B, Peh WCG. Spectrum of papillary lesions of the breast: clinical, imaging, and pathologic correlation. AJR Am R Roentgenol. 2008;191:700–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaffer S, Nagi C, Bleiweiss IJ. Excision is indicated for intraductal papilloma of the breast diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Cancer. 2009;115:2837–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavassoli FA. Papillary lesions. In: Tavassoli FA, editor. Pathology of the breast. Appleton & Lange; Norwalk, CT: 1999. pp. 325–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Tizol-Blanco DM, Gould EW. Papillomas and atypical papillomas in breast core needle biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:217–21. doi: 10.1309/K1BN-JXET-EY3H-06UL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agoff SN, Lawton TJ. Papillary lesions of the breast with and without atypical ductal hyperplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:440–3. doi: 10.1309/NAPJ-MB0G-XKJC-6PTH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohn V, Keylock J, Arthurs Z, et al. Breast papillomas in the era of percutaneous needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2979–84. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivan D, Selinko V, Sahin AA, et al. Accuracy of core needle biopsy diagnosis in assessing papillary breast lesions: histologic predictors of malignancy. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:165–71. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Oken SM, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast at percutaneous core-needle biopsy. Radiology. 2006;238:801–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2382041839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valdes EK, Tartter PA, Genelus-Dominique E, Guilbaud DA, Rosenbaum-Smith S, Estabrook A. Significance of papillary lesions at percutaneous breast biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:480–2. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puglisi F, Zuiani C, Bazzocchi M, et al. Role of mammography, ultrasound, and large core biopsy in the diagnostic evaluation of papillary breast lesions. Oncology. 2003;65:311–5. doi: 10.1159/000074643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs TW, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ. Nonmalignant lesions in breast core needle biopsies: to excise or not to excise? Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1095–110. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashkenazi I, Ferrer K, Sekosan M, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast discovered on percutaneous large core and vacuum-assisted biopsies: reliability of clinical and pathological parameters in identifying benign lesions. Am J Surg. 2007;194:183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora N, Hill C, Hoda SA, Rosenblatt R, Pigalarga R, Tousimis EA. Clinicopathological features of papillary lesions on core needle biopsy of the breast predictive of malignancy. Am J Surg. 2007;194:444–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kil WH, Cho EY, Kim JH, Nam SJ, Yang JH. Is surgical excision necessary in benign papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core biopsy? Breast. 2007;17:258–62. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCulloch GL, Evans AJ, Yeoman L, et al. Radiological features of papillary carcinoma of the breast. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:865–8. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(97)80083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberman L, Tornos C, Huzjan R, Bartella L, Morris EA, Dershaw DD. Is surgical excision warranted after benign, concordant diagnosis of papilloma at percutaneous breast biopsy? AJR Am J Roentengol. 2006;186:1328–34. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakr R, Rouzier R, Salem C, Antoine M, Chopier J, Darai E, Uzan S. Risk of breast cancer associated with papilloma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1304–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soo MS, Williford ME, Walsh R, et al. Papilllary carcinoma of the breast: imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:321–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.2.7839962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woods ER, Helvie MA, Ikeda DM, et al. Solitary breast papilloma: comparison of mammographic, galactographic, and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:487–91. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.3.1503011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin JH, Kim HH, Kim SM, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast diagnosed at percutaneous sonographically guided biopsy: comparison of sonographic features and biopsy methods. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:630–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cassano E, Urban LA, Pizzamiglio M, et al. Ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted core breast biopsy: experience with 406 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:103–10. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carder PJ, Khan T, Burrows P, Sharma N. Large volume “mammotome” biopsy may reduce the need for diagnostic surgery in papillary lesions of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 2008;81:928–33. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.057158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zografos GC, Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, et al. Diagnosing papillary lesions using vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: should conservative or surgical management follow? Onkologie. 2008;31:653–6. doi: 10.1159/000165053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]