SUMMARY

The hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1 has recently been identified as an important modifier of longevity in the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans. Studies have reported that HIF-1 can function as both a positive and negative regulator of lifespan, and several disparate models have been proposed for the role of HIF in aging. Here, we resolve many of the apparent discrepancies between these studies. We find that stabilization of HIF-1 increases life span robustly under all conditions tested; however, deletion of hif-1 increases life span in a temperature-dependent manner. Animals lacking HIF-1 are long-lived at 25°C but not at 15°C. We further report that deletion or RNAi knock-down of hif-1 impairs healthspan at lower temperatures due to an age-dependent loss of vulval integrity. Deletion of hif-1 extends life span modestly at 20°C when animals displaying the vulval integrity defect are censored from the experimental data, but fails to extend life span if these animals are included. Knock-down of hif-1 results in nuclear relocalization of the FOXO transcription factor DAF-16, and DAF-16 is required for life span extension from deletion of hif-1 at all temperatures regardless of censoring.

Keywords: HIF-1α, longevity, healthspan, DAF-16, Caenorhabditis elegans, hypoxic response

INTRODUCTION

Appropriately altering cellular physiology and gene expression in response to changing oxygen availability is essential for survival. The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is a highly conserved transcriptional regulator of genes involved in this process (Maxwell et al. 2001; Webb et al. 2009). HIF exists as a heterodimer of the regulated HIF-α subunit and the constitutively expressed HIF-β subunit (Wang et al. 1995). Under normoxic conditions, HIF-α is ubiquitinated by a cullin E3 ligase complex containing the von Hippel Lindau protein (VHL) substrate recognition subunit and targeted for proteasomal degradation (Maxwell et al. 1999). This ubiquitination reaction is inhibited by hypoxia, leading to stabilization of HIF-α and induction of the hypoxic response (Kim & Kaelin 2003). The mechanism of ubiquitin-mediated regulation of HIF-α stability is conserved from nematodes to humans.

The Caenorhabditis elegans hypoxic response has been characterized through a series of genetic, biochemical, and microarray studies (Shen & Powell-Coffman 2003; Shen et al. 2005). Loss of HIF-α (hif-1) causes sensitivity to hypoxia, and many mRNAs have been shown to be induced by hypoxia in a HIF-1-dependent manner (Jiang et al. 2001). Deletion of the gene coding for the von Hippel Lindau homolog, VHL-1, results in stabilization of HIF-1 due to its failure to be ubiquitinated and proteasomally degraded (Epstein et al. 2001). Similar to wild type animals subjected to hypoxia, vhl-1(ok161) animals show elevated levels of HIF-1 and activation of HIF-1 target genes (Bishop et al. 2004; Shen et al. 2005; Mabon et al. 2008). Interestingly, a relationship between longevity and resistance to hypoxic stress has been noted: several mutant alleles of daf-2 confer resistance to hypoxia (Scott et al. 2002; Mabon et al. 2009), and a genome-wide RNAi screen identified 11 previously known longevity genes as regulators of hypoxia resistance (Mabon et al. 2008).

We have recently reported a direct connection between HIF-1 and aging, with the finding that stabilization of HIF-1 by RNAi knock-down of vhl-1, or by deletion of vhl-1, leads to a significant increase in life span (Mehta et al. 2009). Life span extension from deletion of vhl-1 is suppressed by deletion of hif-1, and is genetically distinct from the insulin-like signaling pathway and from dietary restriction (DR). Stabilization of HIF-1 also enhances healthspan, as measured by resistance to polyglutamine toxicity, resistance to amyloid beta toxicity, and accumulation of autoflourescent age pigment (Mehta et al. 2009).

Since our report, four additional studies from different groups have implicated the hypoxic response in nematode aging. Chen et al. (Chen et al. 2009) first described an opposite role for HIF-1, by showing that deletion of hif-1 can also increase life span, a finding which has been independently confirmed by two additional studies (Bellier et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009). Chen et al. (Chen et al. 2009) reported that life span extension from deletion of hif-1 occurs independently of DAF-16, and proposed that HIF-1 acts as a negative regulator of life span downstream of DR by modulating the response to ER stress. This model differs from that of Zhang et al. (Zhang et al. 2009) who report that life span extension from deletion of HIF-1 requires DAF-16.

In addition to showing that loss of HIF-1 can increase life span, Zhang et al. (Zhang et al. 2009) also confirmed that stabilization of HIF-1 increases life span. They reported that transgenic overexpression of either wild type HIF-1, or a non-degradable allele of HIF-1, is sufficient to enhance longevity by a DAF-16-independent mechanism. The pro-longevity role of HIF-1 was then further validated by Muller et al. (Muller et al. 2009) who verified that deletion of vhl-1 increases life span in a DAF-16-independent manner. Under their conditions, however, the life span extension from vhl-1(RNAi) appeared to be partially HIF-1-independent, leading them to propose that vhl-1 modulates longevity by both HIF-1-dependent and HIF-1-independent mechanisms.

The data described in these five studies define a key role for HIF-1 and the hypoxic response in aging, but they also raise an important question: How can HIF-1 play both a pro- and anti-longevity role at the same time? Here we address this question by showing that life span extension from stabilization of HIF-1 is independent of temperature between 15–25°C, but life span extension from loss of HIF-1 is temperature-dependent, occurring only at higher temperatures. We further report that knock-down of HIF-1 results in nuclear localization of the FOXO transcription factor DAF-16, and that life span extension resulting from deletion of hif-1 is suppressed by mutation of daf-16. The failure of hif-1 deletion to increase life span at lower temperatures arises, at least in part, from a variable-penetrance, age-associated vulval integrity defect, resulting in diminished healthspan and longevity.

RESULTS

Life span extension from hif-1 deletion, but not HIF-1 stabilization, is temperature-dependent

In order to clarify the apparent contradiction between our observation that deletion of hif-1 has no effect on life span (Mehta et al. 2009) and the report by Chen et al. (Chen et al. 2009) that deletion of hif-1 increases life span, we explored potential explanations for this difference. One difference that we identified between the two studies was the temperature at which life span was examined; we used 20°C while the other study used 25°C (Kaeberlein & Kapahi 2009). In order to test the possibility that experimental temperature might influence the effect of hif-1 deletion on life span, we measured survival of N2 wild type and hif-1(ia4) animals maintained at either 25°C, 20°C, or 15°C. Consistent with prior data (Chen et al. 2009), we observed that hif-1(ia4) animals lived significantly longer than N2 animals at 25°C (Figure 1; Supplemental Table 1). At 20°C or 15°C, the life span of hif-1(ia4) animals was not significantly different from N2 animals.

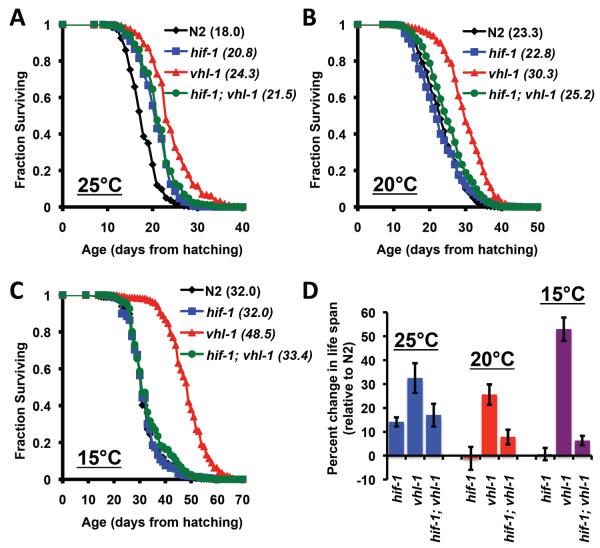

Figure 1. Temperature influences the effect of HIF-1 deletion but not HIF-1 stabilization.

Life span from hatching was determined for N2, vhl-1(ok161), hif-1(ia4), and hif-1(ia4); vhl-1(ok161) animals at (A) 15°C, (B) 20°C, and (C) 25°C. Mean life span is shown in parentheses. Deletion of vhl-1 significantly increased median life span at all three temperatures, while deletion of hif-1 only significantly increased life span at 25°C. A minimum of 350 animals and three replicate experiments were examined for each genotype at each temperature. Pooled data are shown. Summary data and statistics for individual and pooled experimental data are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Since deletion of hif-1 modulated longevity in a temperature-dependent manner, we next asked whether life span extension from stabilization of HIF-1 was also temperature-dependent. In contrast to hif-1(ia4) animals, vhl-1(ok161) animals were long-lived at 15°C, 20°C, and 25°C, relative to N2 (Figure 1; Supplemental Table 1). At all three temperatures, vhl-1(ok161) animals were also significantly longer lived than hif-1(ia4) animals. Deletion of hif-1 largely suppressed life span extension from deletion of vhl-1; however, hif-1(ia4); vhl-1(ok161) animals were slightly longer-lived than hif-1(ia4) animals at 25°C and 20°C (Figure 1; Supplemental Table 1). Our prior study (Mehta et al. 2009) failed to detect a statistically significant difference in life span between hif-1(ia4) and hif-1(ia4); vhl-1(ok161) animals, perhaps due to a slight variation in experimental temperature between these two studies.

Loss of HIF-1 causes a temperature-dependent increase in vulval integrity defects

While performing the life span experiments on hif-1(ia4) animals, we noted elevated frequencies of vulval protrusion (Pvl, Wormbase phenotype WBPhenotype:0000697) which progressed in a majority of animals soon thereafter to vulval rupture (Rup, Wormbase phenotype WBPhenotype:0000038). Vulval rupture (also referred to as “exploded through vulva”) can be observed when the animal displays an extrusion of the internal organs through the vulva (Figure 2a–d). For simplicity, we will refer to both of these phenotypes as a vulval integrity defect (Vid) hereafter. The molecular basis of Vid is not well understood; however, Pvl and Rup are relatively common phenotypes, having been annotated on Wormbase for 1403 and 449 RNAi experiments, respectively (Harris et al. 2010). To the best of our knowledge, deletion or RNAi knock-down of hif-1 has not been previously described to cause Vid, nor has this phenotype been previously associated with aging.

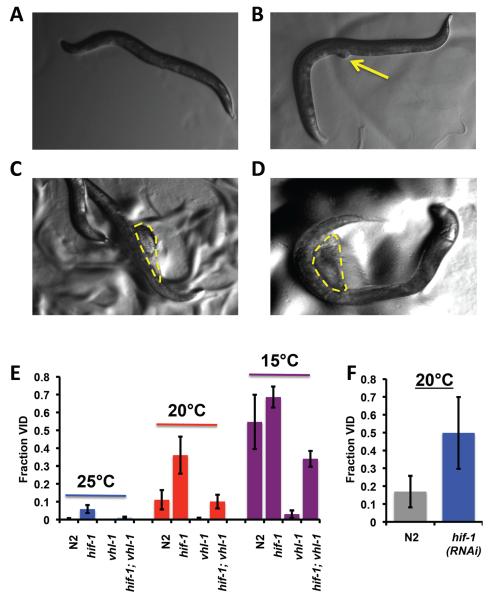

Figure 2. Loss of HIF-1 impairs healthspan due to a defect in vulval integrity.

Panels A-D show a representative example of the vulval integrity defect (Vid) observed in hif-1(ia4) animals across their entire life time. The vulval integrity defect is typically first detected morphologically when (A) healthy worms begin to show a (B) protruding vulva. This usually progresses through stages of (C) early rupture and (D) late rupture prior to death. Panel E shows the total fraction of N2, hif-1(ia4), vhl-1(ok161), and hif-1(ia4); vhl-1(ok161) animals displaying a vulval integrity defect prior to death at 25°C, 20°C and 15°C, respectively. Panel F shows the increase in vulval integrity defect of hif-1(RNAi) treatment from egg at 20°C. A, B and C are viewed at 70× magnification, and D is viewed at 75× magnification. Error bars represent SEM. Summary data and statistics for individual and pooled experimental data are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

The penetrance of Vid was clearly temperature dependent, with higher frequencies of Vid occurring at 15°C, compared to 20°C (Figure 2e; Supplemental Table 2). Vid occurred rarely at 25°C. Although the frequency of Vid varied from experiment to experiment (Supplemental Table 2), it was always the case that hif-1(ia4) animals showed a significantly greater frequency than N2 animals, while vhl-1(ok161) animals had a reduced level of Vid (Figure 2e). Animals with both vhl-1 and hif-1 deleted had an intermediate level of Vid, indicating that hif-1 is only partially epistatic to vhl-1 for this phenotype. RNAi knock-down of hif-1 resulted in a similarly elevated level of Vid (Figure 2f), demonstrating that this phenotype results from reduced HIF-1 abundance.

The appearance of Vid showed a striking age-dependence. At 20°C, Vid was rarely observed during the first week of life, when animals are developing and reproductively active (Figure 3). During the second week of life, the percentage of animals showing Vid increased and then leveled off. Vid was never observed after the 20th day of life at this temperature, even though a majority of animals were still alive and lived for several additional days. The same trend was observed at 15°C, but occurred about one week later, likely due to the slower rate of development and aging at lower temperatures. Based on these observations, we propose that Vid represents an age-dependent loss of healthspan that is modulated by both temperature and HIF-1.

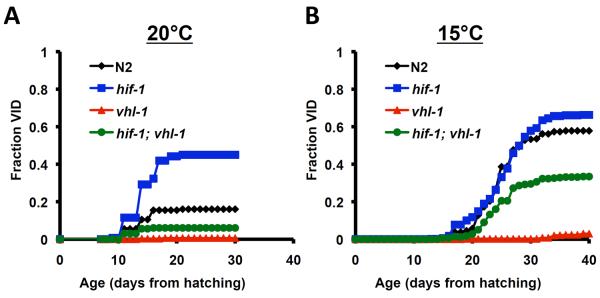

Figure 3. Loss of vulval integrity is an age-dependent healthspan phenotype.

The fraction of animals with observable vulval integrity defects (Vid) are shown as a function of age from hatching for N2, hif-1(ia4), vhl-1(ok161), and hif-1(ia4); vhl-1(ok161) at (A) 20°C and (B) 15°C.

Many laboratories censor “ruptured” or “exploded” animals from life span experiments because this phenotype is not considered to be a part of the normal aging process; however, it has been our policy not to exclude animals from our longevity experiments whenever possible. Interestingly, when Vid animals are censored from our data set, deletion of hif-1 results in a significant, albeit modest, increase in life span at 20°C (Figure 4; Supplemental Table 3). Censoring of Vid animals failed to yield a significant life span extension in hif-1(ia4) animals at 15°C (Figure 4; Supplemental Table 3).

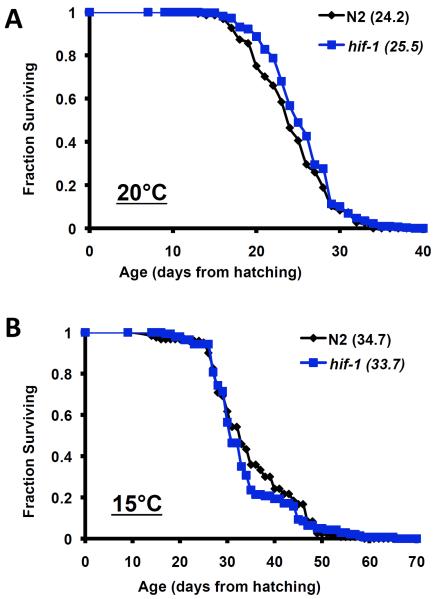

Figure 4. Deletion of hif-1 increases life span when animals exhibiting a vulval integrity defect are censored.

Reanalysis of our longevity data removing animals displaying loss of vulval integrity. Censored life span from hatching is shown for N2 and hif-1(ia4) animals at (A) 20°C and (B) 15°C. Censoring results in a significant increase in life span of hif-1(ia4) animals at 20°C but not 15°C. Summary data and statistics for individual and pooled experimental data are provided in Supplemental Table 3.

DAF-16/FOXO relocalizes to the nucleus in response to loss of HIF-1 and is required for life span extension

We next explored the nature of the temperature-dependent life span extension from deletion of hif-1. Since life span extension from stabilization of HIF-1 is independent of DAF-16 (Mehta et al. 2009), we wondered whether deletion of hif-1 would also extend life span in a DAF-16-independent manner. Relative to daf-16(mu86) single mutants, daf-16(mu86); hif-1(ia4) double mutant animals were not long-lived at any of the three temperatures tested (Figure 5; Supplemental Table 4). Life span extension from hif-1 deletion at 20°C when Vid animals were censored was similarly DAF-16-dependent (Figure 6; Supplemental Table 5). The elevated frequency of Vid caused by mutation of hif-1 was only partially suppressed by mutation of daf-16 (Supplemental Table 2).

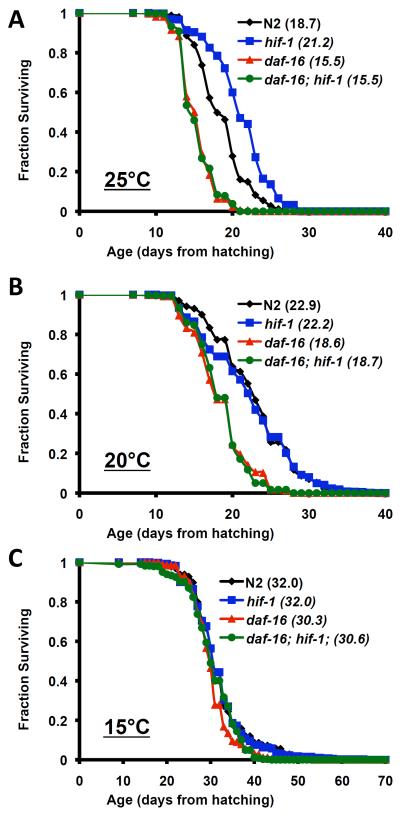

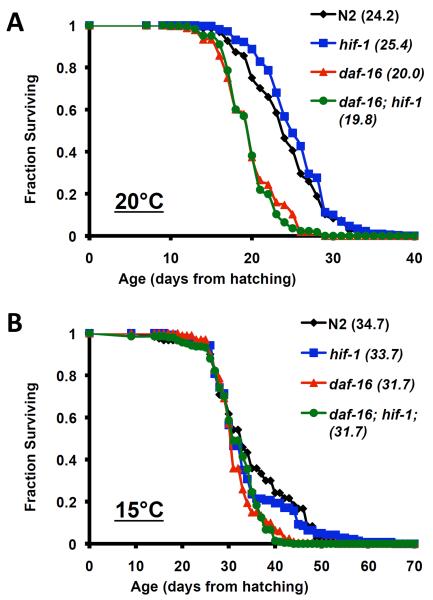

Figure 5. DAF-16 is required for life span extension from deletion of hif-1.

Life span from hatching was determined for N2, daf-16(mu86), hif-1(ia4), and daf-16(mu86); hif-1(ia4) animals at (A) 25°C, (B) 20°C, and (C) 15°C. Mean life span is shown in parentheses. Deletion of hif-1 failed to significantly increase life span of daf-16(mu86) animals at any temperature. Summary data and statistics for individual and pooled experimental data are provided in Supplemental Table 4.

Figure 6. DAF-16 is still required for life span extension from deletion of hif-1 when animals with vulval integrity defects are censored.

Reanalysis of the longevity data from Figure 5 removing animals displaying loss of vulval integrity at (A) 20°C and (B) 15°C. Mean life span is shown in parentheses. Summary data and statistics for individual and pooled experimental data are provided in Supplemental Table 5.

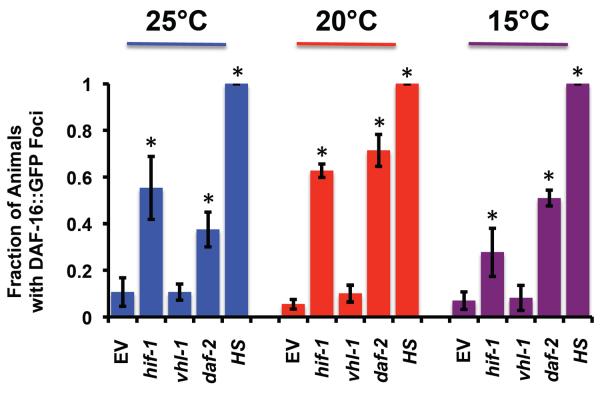

Although suppression of life span extension by mutation of daf-16 is consistent with the idea that DAF-16 acts downstream of HIF-1, it may also be the case that loss of DAF-16 prevents life span extension by indirect mechanisms. To determine whether DAF-16 function is altered in animals lacking HIF-1, we used a previously described DAF-16∷GFP reporter strain to monitor localization of DAF-16 (Henderson & Johnson 2001). Similar to mammalian FOXO transcription factors, translocation of DAF-16 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is required for activation, and has been observed in animals with reduced insulin-like signaling and in response to stresses such as heat shock or starvation (Calnan & Brunet 2008). Interestingly, RNAi knock-down of hif-1 resulted in translocation of DAF-16 to the nucleus to an extent comparable to knock-down of the insulin-like receptor daf-2 (Figure 7; Supplemental Figure 1). These experiments were performed at atmospheric oxygen levels, indicating that basal HIF-1 activity promotes cytoplasmic localization of DAF-16 under normoxic conditions and supporting the idea that temperature-dependent life span extension from loss of hif-1 results from activation of DAF-16. In contrast to loss of hif-1, stabilization of hif-1 by deletion of vhl-1 had no effect on nuclear localization of DAF-16∷GFP. This is consistent with prior reports that life span extension from deletion of vhl-1 does not require DAF-16 (Mehta et al. 2009; Muller et al. 2009)

Figure 7. hif-1 RNAi causes nuclear relocalization of DAF-16∷GFP.

(A) Fraction of animals showing distinct DAF-16∷GFP puncta following 2 hour treatments of either empty vector RNAi (EV), 37° heat shock (heat), daf-2(RNAi), hif-1(RNAi), or vhl-1(RNAi) at 15°, 20°, and 25°. *denotes p-value of less than 0.05 relative to EV by one-way ANOVA. Representative images of animals are provided in Supplemental Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

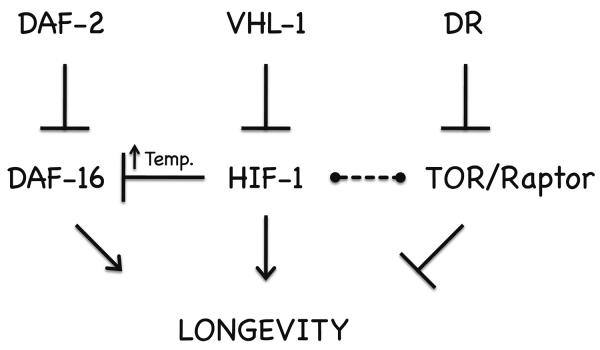

HIF-1 has recently been reported to both promote and repress longevity in C. elegans, leading to confusion regarding the role of the hypoxic response in aging (Leiser & Kaeberlein). These apparent contradictions can be partially explained by the observation that experimental temperature and censoring of Vid animals both influence the effect of hif-1 deletion on life span. Our observation that RNAi knock-down of hif-1 causes relocalization of DAF-16 to the nucleus suggests that HIF-1 acts as a repressor of DAF-16 under normoxic conditions, and is consistent with suppression of life span extension in hif-1(ia4) animals by a null allele of daf-16. In contrast to deletion of hif-1, stabilization of HIF-1 by deletion of vhl-1 robustly increases life span at all three temperatures tested, and prior studies have indicated that this life span extension is genetically distinct from insulin-like signaling and DR (Mehta et al. 2009; Muller et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009). Taken together, these data suggest a model in which stabilization of HIF-1 can promote longevity and healthspan regardless of temperature by inducing hypoxic response target genes under normoxic conditions, while deletion of hif-1 can promote longevity by activation of DAF-16 at high temperature (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Model for HIF-1 modulation of longevity in C. elegans.

Stabilization of HIF-1 promotes longevity by a mechanism distinct from both insulin-like signaling and dietary restriction (DR). HIF-1 also negatively impacts longevity by repressing nuclear localization and activation of DAF-16, in a temperature-dependent manner. HIF-1 also interacts with TOR/Raptor and the DR pathway, but in a complex manner dependent on additional experimental variables that are currently unknown (represented by dashed lines).

Although we have reconciled the contradictory data regarding life span extension from deletion of hif-1, our model still differs from that of Chen et al. (Chen et al. 2009), who proposed that deletion of hif-1 increases life span by a mechanism related to DR and involving the ER stress response factor IRE-1. This model was based, in part, upon their observation that hif-1(RNAi) increased the life span of daf-16(mgDF47) animals (Chen et al. 2009). In contrast to this, we found that the hif-1(ia4) mutation did not increase the life span of daf-16(mu86) animals, consistent with the data of Zhang et al. (Zhang et al. 2009). Although both daf-16 alleles are thought to be null alleles, it is possible that different daf-16 alleles interact differently with loss of HIF-1. It is also possible that hif-1(RNAi) and hif-1(ia4) reduce HIF-1 activity to a different extent or in a different manner. For example, it may be the case that RNAi knock-down reduces HIF-1 activity to a variable extent in different cell types, while deletion of hif-1 results in loss of HIF-1 activity in all cells. It will be of interest to determine which cell types are most important for life span extension from loss of HIF-1 as well as stabilization of HIF-1.

DAF-16 and HIF-1 interact in a complex manner

DAF-16 and HIF-1 are both stress-responsive transcription factors that promote longevity. Our data suggest that HIF-1 impairs nuclear localization of DAF-16∷GFP under normoxic conditions, providing a previously unexpected connection between these two proteins. An important question is whether this effect of HIF-1 on DAF-16 is direct or indirect. We cannot currently differentiate between these two possibilities, but we speculate that loss of basal HIF-1 activity is perceived as a stress signal even under normoxic conditions, and that this signal is sufficient to cause DAF-16 to become activated.

Similar to mammalian FOXO transcription factors, DAF-16 localization is regulated by at least three post-translational modifications: phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination (Calnan & Brunet 2008). Several aging-related factors are known to influence DAF-16 localization and activity. For example, the C. elegans AMP kinase catalytic subunit AAK-2 is able to phosphorylate at least 6 residues on DAF-16 (Greer et al. 2007). Likewise, Cst1, Akt and Jnk are all known to phosphorylate DAF-16 to modulate its localization and activity (Lehtinen et al. 2006; Mukhopadhyay 2006). Polyubiquitination of DAF-16 is modulated by the RLE1 ubiquitin ligase (Li et al. 2007) and acetylation of DAF-16 is influenced by the SIR-2.1 protein deacetylase (Berdichevsky et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2006). This latter interaction may be particularly relevant here, as the mammalian SIR-2.1 ortholog SIRT1 has recently been reported to deacetylate both HIF-1α and HIF-2α (Dioum et al. 2009; Leiser & Kaeberlein 2010; Lim et al. 2010). It will be of interest to determine how post-translational modification of DAF-16 is altered by reduced expression of hif-1 and the extent to which this regulation is conserved in other species.

It is also noteworthy that, despite the fact that hif-1 RNAi induces DAF-16∷GFP nuclear localization to an extent similar to daf-2 RNAi at 20°C and 15°C, deletion of hif-1 does not extend life span at these temperatures. One possible explanation is that DAF-16 target genes important for longevity are not activated by loss of hif-1 at 15°C, despite nuclear localization of DAF-16. It is also possible that DAF-16 activity is regulated differently in hif-1(ia4) animals that completely lack HIF-1 activity from hatching, as compared to animals subjected to RNAi knock-down of hif-1. We note that there are additional examples of interventions that induce DAF-16∷GFP nuclear localization without extending life span, demonstrating that nuclear localization of DAF-16 is not always sufficient to promote longevity in C. elegans (Yamawaki et al. 2008).

Vulval integrity and healthspan in C. elegans

Healthspan can be defined as the period of life spent in relatively good health, and maintenance of healthspan is recognized as an important component of aging (Tatar 2009). Measures of healthspan have been proposed in C. elegans, including retention of motility during aging, accumulation of auto-fluorescent age pigment, and resistance to proteotoxic stress (Huang et al. 2004; Gerstbrein et al. 2005; Steinkraus et al. 2008). We have previously reported improved healthspan in vhl-1(ok161) animals by two of these measures, reduced accumulation of age-pigment and enhanced resistance to proteotoxic stress (Mehta et al. 2009).

We propose that maintenance of vulval integrity is another potentially important measure of nematode healthspan that should be considered during longevity studies. In wild type animals, loss of healthspan due to Vid occurs post-reproductively in a relatively small percentage of the population. The frequency of Vid is temperature-dependent, occurring more often at lower temperatures, at least within the range of 15–25°C. Loss of healthspan due to Vid is significantly greater in hif-1(ia4) animals than N2 animals, and may explain some of the differences observed in prior studies with respect to effect of hif-1 deletion on life span. Consistent with this possibility, we note that Zhang et al. (Zhang et al. 2009), excluded animals that “burst at the vulva” and observed life span extension at 20°C. The frequency of Vid is significantly reduced in vhl-1(ok161) animals, relative to N2, at both 20°C and 15°C, providing further evidence that loss of vhl-1 enhances both life span and healthspan in C. elegans.

Reduced healthspan due to Vid has been previously associated with RNAi knock-down of mRNA translation factors, although this relationship has not been carefully examined. Specifically, Hansen et al. (Hansen et al. 2007) reported that “translation associated RNAi clones, in particular TOR RNAi, often induced a slightly higher level of rupturing”. Similar to Zhang et al. (Zhang et al. 2009), ruptured animals were censored from the life span analysis in these experiments (Hansen et al. 2007). It is also unknown whether the enhanced frequency of Vid associated with translation-related RNAi clones is temperature-dependent as in the case of hif-1(ia4), since Hansen et al. (Hansen et al. 2007) performed all of their life span studies at 20°C.

The observation that deletion of hif-1 and some translation-related longevity interventions negatively impact healthspan while positively impacting life span represents an important demonstration that longevity and healthspan are not always coupled. Although we have generally chosen not to censor animals that fail to maintain vulval integrity from our longevity analysis, this is common practice among some laboratories, and a discussion of how to appropriately address this phenotype is warranted. It will also be of interest to determine which additional longevity interventions or experimental conditions other than temperature influence the frequency of Vid.

Role of the hypoxic response in mammalian aging

The function of HIF-1 as both a positive and negative modulator of longevity and healthspan in C. elegans raises the question as to whether mammalian HIF plays any similar roles. It is unknown whether mammalian FOXO proteins are activated by knock-down of HIF, but if this response is conserved, then it is reasonable to speculate that reduced HIF activity under normoxic conditions may be beneficial against age-associated disease. Interestingly, FOXO4 has been reported to regulate HIF-1α activity (Dimova et al. 2010), suggesting that FOXO and HIF transcription factors are likely to interact in a complex manner in mammals.

HIF-1α has been implicated as an important factor in human healthspan. One study found that a specific HIF-1α allele is associated with athletic skill and fast twitch muscle fiber predominance in weight lifters (Ahmetov et al. 2008), while additional studies have indicated that elite athletes show a higher sensitivity of HIF-1α during an acute hypoxic test (Mounier et al. 2009; Pialoux et al. 2009). Mutation of the VHL-1 ortholog results in von Hippel Lindau symdrome, an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by a variety of tumors, particularly angiomas and hemangioblastomas (Iliopoulos & Kaelin 1997). Clearly, therefore, human healthspan can be negatively impacted by constitutive stabilization of HIF, but it may be the case that altered sensitivity of the hypoxic response or partial stabilization, perhaps in a tissue-specific manner, can also prove beneficial. As the downstream targets of HIF-1 involved in promoting longevity and healthspan are identified in C. elegans, it may be possible to modulate HIF function in mammals to slow aging and the delay progression of age-related diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions

Standard procedures for C. elegans strain maintenance and manipulation were used, as previously described (Kaeberlein et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008; Sutphin & Kaeberlein 2008). Except for RNAi experiments, all experimental procedures were performed on animals fed UV-killed E. coli OP50 from hatching. Experimental animals were maintained on solid Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin. Except where stated otherwise, experiments were performed on animals maintained at 20°C. Nematode strains used in this study are described in Supplemental Table 6. For RNAi experiments, animals were maintained on RNAi feeding strains. RNAi plates consisted of NGM supplemented with 1mM β-D-isothiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 25 μg/ml carbenicillin. Unless otherwise indicated, worms were raised on RNAi bacteria from hatching. RNAi clones were verified by sequencing the region of the RNAi plasmid expressing the double-stranded RNA after purification from the corresponding bacterial clone and by phenotypic analysis of animals maintained on the RNAi bacteria. Sequence verification of the RNAi clones used in this study has been previously published (Mehta et al. 2009).

Life span analysis

Life span analyses were carried out as described (Sutphin & Kaeberlein 2009). Statistical analysis and replication of life span experiments is provided in Supplemental Tables 1–5. Ruptured animals were not censored from life span experiments, except where indicated in Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 3. Animals that foraged off the surface of the plate during the course of the experiment were not considered.

Quantification of DAF-16∷GFP puncta

Fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Zeiss SteREO Lumar.V12 microscope as previously described (Steinkraus et al. 2008; Mehta et al. 2009). Eggs were prepared from gravid DAF-16∷GFP adult worms and placed on NGM with EV or RNAi bacteria. Animals were grown at 20°C for 3 days and then treated with specific RNAi or heat shock (37°C) for 2 hours, before being imaged using a Zeiss SteREO Lumar.V12 microscope as previously described (Steinkraus et al. 2008). Fluorescence microscopy was performed. Animals were paralyzed with 25mM sodium azide and placed on a teflon printed 8-well glass slide with 6mm well diameter (Electron Microscopy Sciences). The GFP filter (470/40 excitation band-pass filter and 525/50 emission band pass filter) was employed for imaging the DAF-16∷GFP worms at 150X magnification with exposure time of 40 ms for bright field and 500 ms for GFP filter. The Image J 1.341.5.0_07 software was employed for inverting the images and converting them to 32-bit format and then manually counting the worms for the presence or absence of distinct GFP puncta.

Statistical analysis

A Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test (MATLAB `ranksum' function) was used to generate p-values to determine statistical significance for life span assays. The mean life spans, number of animals, number of replicate experiments, and p-values are provided in Supplemental Tables 1–5. A 2-tailed Student's T-test was performed using the TTEST function in Microsoft Excel to calculate p-values for DAF-16∷GFP positive worms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank J. Brice for technical assistance. We would also like to thank J. Powell-Coffman for providing nematode strains, and P. Larsen and D. Miller for helpful discussion. Some nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). This work was supported in part by NIH Grant R01AG031108 to MK. SL was supported by NIH Grant T32AG000057. MK is an Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar in Aging.

Footnotes

Author Contributions - MK and SFL conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. Experimental work was performed by SFL and AB.

References

- Ahmetov II, Hakimullina AM, Lyubaeva EV, Vinogradova OL, Rogozkin VA. Effect of HIF1A gene polymorphism on human muscle performance. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2008;146:351–353. doi: 10.1007/s10517-008-0291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellier A, Chen CS, Kao CY, Cinar HN, Aroian RV. Hypoxia and the hypoxic response pathway protect against pore-forming toxins in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000689. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdichevsky A, Viswanathan M, Horvitz HR, Guarente L. C. elegans SIR-2.1 interacts with 14-3-3 proteins to activate DAF-16 and extend life span. Cell. 2006;125:1165–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop T, Lau KW, Epstein AC, Kim SK, Jiang M, O'Rourke D, Pugh CW, Gleadle JM, Taylor MS, Hodgkin J, Ratcliffe PJ. Genetic analysis of pathways regulated by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan DR, Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276–2288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Thomas EL, Kapahi P. HIF-1 modulates dietary restriction-mediated lifespan extension via IRE-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimova EY, Samoylenko A, Kietzmann T. FOXO4 induces human PAI-1 gene expression via an indirect mechanism by modulating HIF-1alpha and CREB levels. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010 doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dioum EM, Chen R, Alexander MS, Zhang Q, Hogg RT, Gerard RD, Garcia JA. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha signaling by the stress-responsive deacetylase sirtuin 1. Science. 2009;324:1289–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1169956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O'Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, Tian YM, Masson N, Hamilton DL, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstbrein B, Stamatas G, Kollias N, Driscoll M. In vivo spectrofluorimetry reveals endogenous biomarkers that report healthspan and dietary restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2005;4:127–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Dowlatshahi D, Banko MR, Villen J, Hoang K, Blanchard D, Gygi SP, Brunet A. An AMPK-FOXO pathway mediates longevity induced by a novel method of dietary restriction in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1646–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Taubert S, Crawford D, Libina N, Lee SJ, Kenyon C. Lifespan extension by conditions that inhibit translation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:95–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TW, Antoshechkin I, Bieri T, Blasiar D, Chan J, Chen WJ, De La Cruz N, Davis P, Duesbury M, Fang R, Fernandes J, Han M, Kishore R, Lee R, Muller HM, Nakamura C, Ozersky P, Petcherski A, Rangarajan A, Rogers A, Schindelman G, Schwarz EM, Tuli MA, Van Auken K, Wang D, Wang X, Williams G, Yook K, Durbin R, Stein LD, Spieth J, Sternberg PW. WormBase: a comprehensive resource for nematode research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D463–467. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson ST, Johnson TE. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Xiong C, Kornfeld K. Measurements of age-related changes of physiological processes that predict lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8084–8089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400848101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulos O, Kaelin WG., Jr The molecular basis of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Mol Med. 1997;3:289–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Guo R, Powell-Coffman JA. The Caenorhabditis elegans hif-1 gene encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that is required for adaptation to hypoxia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:7916–7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141234698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, Kapahi P. The hypoxic response and aging. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2324. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein TL, Smith ED, Tsuchiya M, Welton KL, Thomas JH, Fields S, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. Lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans by complete removal of food. Aging Cell. 2006;5:487–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W, Kaelin WG., Jr The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein: new insights into oxygen sensing and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen MK, Yuan Z, Boag PR, Yang Y, Villen J, Becker EB, DiBacco S, de la Iglesia N, Gygi S, Blackwell TK, Bonni A. A conserved MST-FOXO signaling pathway mediates oxidative-stress responses and extends life span. Cell. 2006;125:987–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiser SF, Kaeberlein M. The hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1 functions as both a positive and negative modulator of aging. Biol Chem. 391:1131–1137. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiser SF, Kaeberlein M. A role for SIRT1 in the hypoxic response. Mol Cell. 2010;38:779–780. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Gao B, Lee SM, Bennett K, Fang D. RLE-1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, regulates C. elegans aging by catalyzing DAF-16 polyubiquitination. Dev Cell. 2007;12:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JH, Lee YM, Chun YS, Chen J, Kim JE, Park JW. Sirtuin 1 modulates cellular responses to hypoxia by deacetylating hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Cell. 2010;38:864–878. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabon ME, Mao X, Jiao Y, Scott BA, Crowder CM. Systematic Identification of Gene Activities Promoting Hypoxic Death. Genetics. 2008 doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.097188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabon ME, Scott BA, Crowder CM. Divergent mechanisms controlling hypoxic sensitivity and lifespan by the DAF-2/insulin/IGF-receptor pathway. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. The pVHL-hIF-1 system. A key mediator of oxygen homeostasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;502:365–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399:271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta R, Steinkraus KA, Sutphin GL, Ramos FJ, Shamieh LS, Huh A, Davis C, Chandler-Brown D, Kaeberlein M. Proteasomal regulation of the hypoxic response modulates aging in C. elegans. Science. 2009;324:1196–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1173507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounier R, Pialoux V, Schmitt L, Richalet JP, Robach P, Coudert J, Clottes E, Fellmann N. Effects of acute hypoxia tests on blood markers in high-level endurance athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:713–720. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1072-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A, Oh SW, Tissenbaum HA. Worming pathways to and from DAF-16/FOXO. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Fabretti F, Zank S, Burst V, Benzing T, Schermer B. The von Hippel Lindau Tumor Suppressor Limits Longevity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pialoux V, Brugniaux JV, Fellmann N, Richalet JP, Robach P, Schmitt L, Coudert J, Mounier R. Oxidative stress and HIF-1 alpha modulate hypoxic ventilatory responses after hypoxic training on athletes. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott BA, Avidan MS, Crowder CM. Regulation of hypoxic death in C. elegans by the insulin/IGF receptor homolog DAF-2. Science. 2002;296:2388–2391. doi: 10.1126/science.1072302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C, Nettleton D, Jiang M, Kim SK, Powell-Coffman JA. Roles of the HIF-1 hypoxia-inducible factor during hypoxia response in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20580–20588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C, Powell-Coffman JA. Genetic analysis of hypoxia signaling and response in C elegans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;995:191–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ED, Kaeberlein TL, Lydum BT, Sager J, Welton KL, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. Age- and calorie-independent life span extension from dietary restriction by bacterial deprivation in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinkraus KA, Smith ED, Davis C, Carr D, Pendergrass WR, Sutphin GL, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. Dietary restriction suppresses proteotoxicity and enhances longevity by an hsf-1-dependent mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutphin GL, Kaeberlein M. Dietary restriction by bacterial deprivation increases life span in wild-derived nematodes. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutphin GL, Kaeberlein M. Measuring Caenorhabditis elegans life span on solid media. J Vis Exp. 2009 doi: 10.3791/1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M. Can we develop genetically tractable models to assess healthspan (rather than life span) in animal models? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:161–163. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Oh SW, Deplancke B, Luo J, Walhout AJ, Tissenbaum HA. C. elegans 14-3-3 proteins regulate life span and interact with SIR-2.1 and DAF-16/FOXO. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:741–747. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JD, Coleman ML, Pugh CW. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF), HIF hydroxylases and oxygen sensing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3539–3554. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamawaki TM, Arantes-Oliveira N, Berman JR, Zhang P, Kenyon C. Distinct activities of the germline and somatic reproductive tissues in the regulation of Caenorhabditis elegans' longevity. Genetics. 2008;178:513–526. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Shao Z, Zhai Z, Shen C, Powell-Coffman JA. The HIF-1 hypoxia-inducible factor modulates lifespan in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.