Abstract

R-spondin proteins sensitize cells to Wnt signalling and act as potent stem cell growth factors. Various membrane proteins have been proposed as potential receptors of R-spondin, including LGR4/5, membrane E3 ubiquitin ligases ZNRF3/RNF43 and several others proteins. Here, we show that R-spondin interacts with ZNRF3/RNF43 and LGR4 through distinct motifs. Both LGR4 and ZNRF3 binding motifs are required for R-spondin-induced LGR4/ZNRF3 interaction, membrane clearance of ZNRF3 and activation of Wnt signalling. Importantly, Wnt-inhibitory activity of ZNRF3, but not of a ZNRF3 mutant with reduced affinity to R-spondin, can be strongly suppressed by R-spondin, suggesting that R-spondin primarily functions by binding and inhibiting ZNRF3. Together, our results support a dual receptor model of R-spondin action, where LGR4/5 serve as the engagement receptor whereas ZNRF3/RNF43 function as the effector receptor.

Keywords: Wnt, R-spondin; ZNRF3, RNF43, LGR4

INTRODUCTION

Wnt proteins regulate cell proliferation, cell polarity and cell fate determination during embryonic development and adult tissue homoeostasis [1]. R-spondins are a group of secreted proteins (RSPO1-4) that potently potentiate Wnt signalling [2]. R-spondins are important in tissue patterning and cell differentiation [3, 4]. R-spondin proteins function as stem cell growth factors and can be used to promote tissue regeneration [5, 6]. R-spondins are also identified for their oncogenic potential in virus and transposon-based mutagenesis screens in mice [7, 8], and they are overexpressed in a subset of colorectal cancers through gene translocation [9]. R-spondin neutralizing agents can potentially be used to treat cancer.

Despite the biological and therapeutic significance, the exact mechanism by which R-spondin increases Wnt signalling is not entirely clear. Various membrane proteins have been reported to bind to R-spondin, including Wnt receptors Frizzled [10] and LRP6 [10, 11], Kremen [12], Syndecan 4 [13], LGR4/5 [14–17] and membrane E3 ubiquitin ligases ZNRF3/RNF43 [18]. Relative contribution of these proteins to R-spondin signalling is not clear. Several models of R-spondin signalling have been proposed, including forming a receptor complex by binding to Frizzled and LRP6 [10], blocking LRP6 turnover by interacting with Kremen [12], enhancing Frizzled internalization by binding to Syndecan 4 [13], promoting LRP6 phosphorylation by binding to LGR4/5 [14, 15]. Our group has recently identified two membrane ubiquitin E3 ligases ZNRF3 and RNF43 that target Wnt receptors for degradation, and shown that R-spondin can simultaneously bind to LGR4 and ZNRF3 and induce membrane clearance of ZNRF3 [18]. On the basis of our results, we proposed that R-spondin potentiates Wnt signalling by inhibiting ZNRF3 and stabilizing Wnt receptors [18]. In this study, we sought to define the signalling mechanism of R-spondin by mapping critical residues of R-spondin for binding to its receptors and for its signalling activity.

RESULTS

Distinct receptor-binding motifs of R-spondin

R-spondin proteins have the same structural organization. They have two adjacent furin-like domains (FU1 and FU2) at the amino terminus, and a thrombospondin (TSP) domain close to the carboxyl terminus (Fig 1A). Sequence similarities of furin-like domains and TSP domain of four RSPO proteins from different species are high, suggesting R-spondin proteins have conserved functions. The TSP domain of R-spondin binds to syndecans and glypicans [13], and might affect cell surface binding of R-spondin. A fragment containing two furin-like domains of R-spondin is sufficient to activate Wnt signalling, and both furin-like domains are required for the signalling activity of R-spondin [3, 16]. How these two furin-like domains engage R-spondin receptors is unknown.

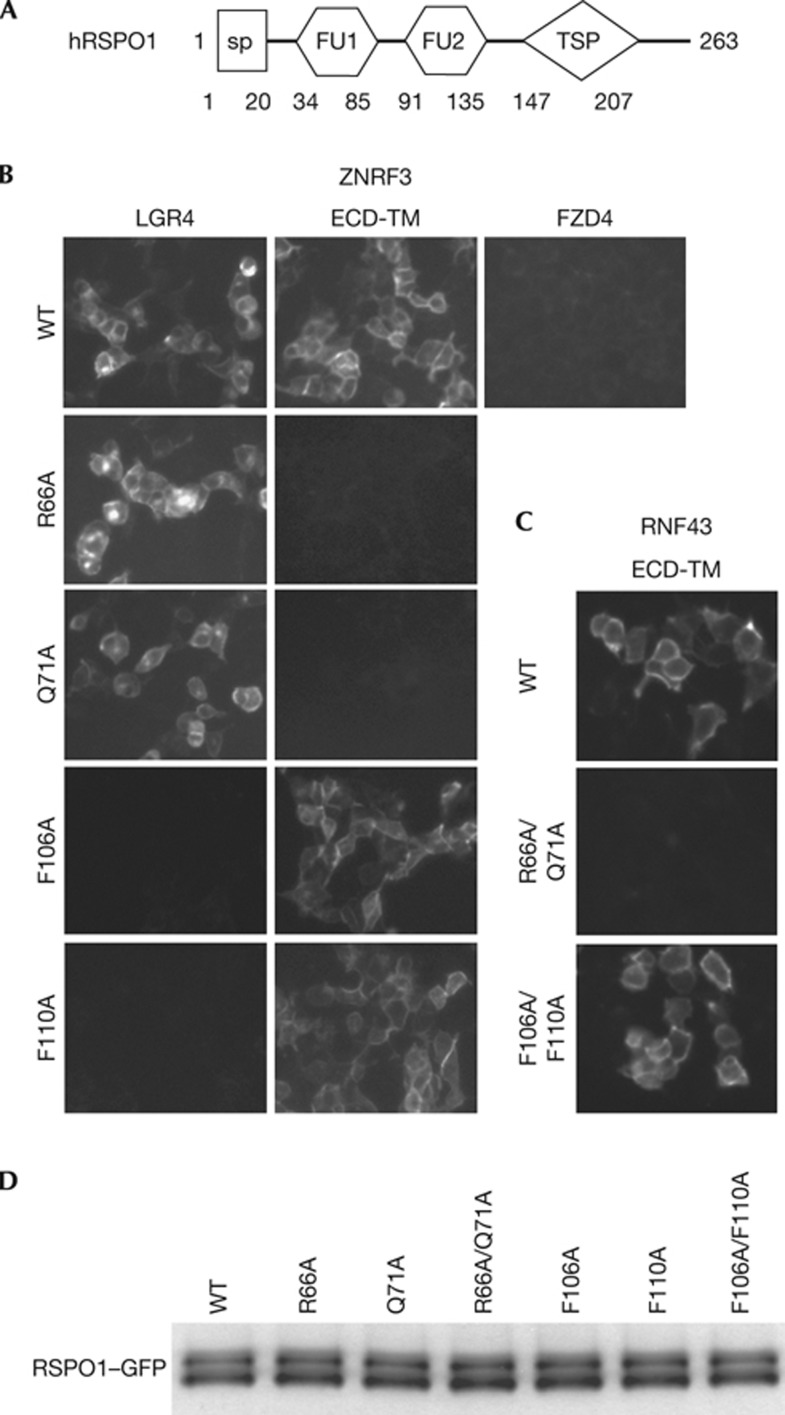

Figure 1.

RSPO1 interacts with LGR4 and ZNRF3 through distinct motifs. (A) A schematic diagram of the domain structure of human RSPO1. (B) Differential binding of RSPO1–GFP mutants to LGR4 and ZNRF3 ECD-TM in a cell-based binding assay. HEK293 cells transiently overexpressing LGR4 or ZNRF3 ECD–TM were incubated with RSPO1–GFP conditioned medium (CM), and binding of RSPO1–GFP was analysed by fluorescence microscopy. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (C) Interaction between WT RSPO1–GFP, R66A/Q71A double mutant or F106A/F110A double mutant and RNF43–ECD-TM in cell-based binding assay. (D) The level of wild-type or mutant RSPO1–GFP used in cell-based binding assay. The level of wild-type or mutant RSPO1–GFP in conditioned medium was determined by western blot using anti-GFP antibody. ECD, extracellular domain; FU1, furin-like domain 1; FU2, furin-like domain 2; GFP, green fluorescent protein; SP, signal peptide; TSP, thrombospondin domain.

As the fragment containing both furin-like domains is sufficient to activate Wnt signalling, this region must be sufficient to interact with R-spondin receptors. To define the signalling mechanism of R-spondin, we mutated all conserved residues within two furin-like domains of RSPO1 and tested their binding to proposed RSPO1 receptors. Consistent with results of other labs [13, 14], we could not detect an interaction between R-spondin and Frizzled, LRP6, or Kremen [18], and, therefore, we focused on LGR4 and ZNRF3. All conserved residues within the furin-like domains of RSPO1–GFP were individually mutated to alanine (supplementary Fig S1 online), and RSPO1–GFP mutants were tested for their interaction with LGR4 and ZNRF3 in a cell-based binding assay (supplementary Table S1 online). Interestingly, mutation of two residues in the furin-like domain 1 (FU1) (R66A or Q71A) abolished the interaction between RSPO1 and ZNRF3, without affecting the interaction between RSPO1 and LGR4 (Fig 1B). We further showed that mutation of two residues of the furin-like domain 2 (FU2) (F106A or F110A) blocked the interaction between RSPO1 and LGR4, without affecting the interaction between RSPO1 and ZNRF3 (Fig 1B). Similar results were obtained using RSPO1 R66A/Q71A or F106A/F110A double mutants (supplementary Fig S2 online). These data suggest that RSPO1 binds to ZNRF3 and LGR4 through distinct domains; the FU1 domain is involved in ZNRF3 binding, whereas the FU2 domain is involved in LGR4 binding. This result is consistent with our previous findings that RSPO1 can bind to both ZNRF3 and LGR4 and induce their dimerization [18]. RNF43 is a functional homologue of ZNRF3 and mediates ubiquitination and degradation of Frizzled [18, 19]. Despite modest homology between the extracellular domain (ECD) of ZNRF3 and RNF43 (40% identity), RSPO1 also bound to RNF43 in the cell-based binding assay (Fig 1C), suggesting that ZNRF3 and RNF43 have conserved function in interacting with R-spondin. RSPO1-RNF43 interaction is abolished by R66A and Q71A double mutation (Fig 1B), while unaffected by F106A and F110A double mutation, indicating that RSPO1 binds to ZNRF3 and RNF43 using the same structural element. The same amount of wild-type or mutant RSPO1–GFP was used in the cell-based binding assay as demonstrated by western blot using anti-GFP antibody (Fig 1D).

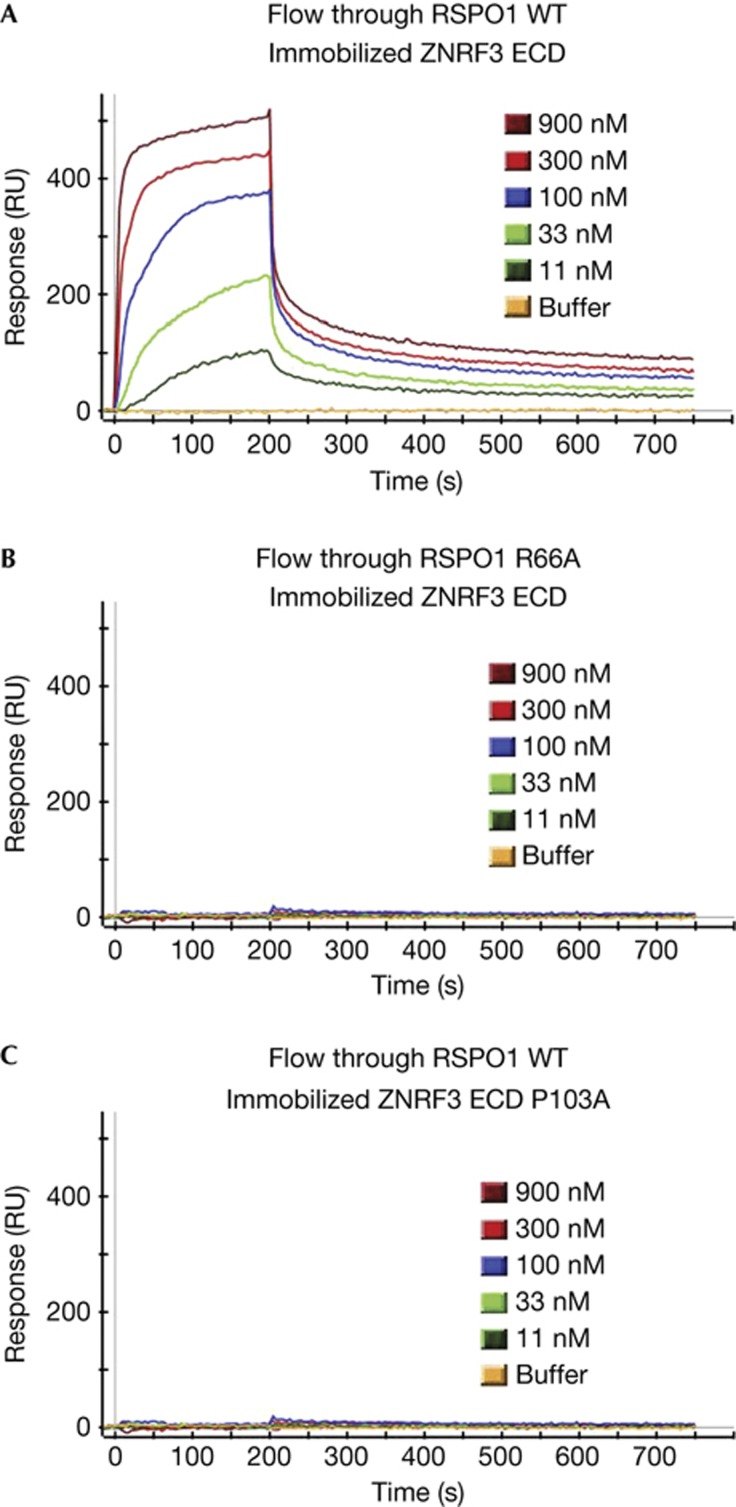

Although the binding between R-spondin and LGR4 or LGR5 has been widely accepted, the physical interaction between R-spondin and ZNRF3 is less well established. We generated recombinant RSPO1 and ZNRF3 ECD proteins with purity over 95%. The binding affinity between RSPO1 and ZNRF3 ECD was measured using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay. As shown in Fig 2A, RSPO1 interacted with ZNRF3 ECD with modest affinity (Kd 0.8 μM). Consistent with results from the cell-based binding assay (Fig 1B), RSPO1 R66A has significantly reduced affinity with ZRNF3 ECD in the SPR assay (Fig 2B). We previously identified a ZNRF3 mutant (P103A) that has significantly reduced interaction with RSPO1 in the cell-based binding assay [18]. Confirming that result, ZNRF3 ECD P103A also has much reduced interaction with RSPO1 in the SPR assay (Fig 2C). Together, these results indicate that RSPO1 specifically binds to ZNRF3, but this binding is significantly weaker than the binding between RSPO1 and LGR4/5 (Kd 8 nM) [15]. The significance of this finding is discussed later.

Figure 2.

Interaction between RSPO1 and ZNRF3 ECD in surface plasmon resonance assay. (A) Interaction between RSPO1 and ZNRF3 ECD. (B) Interaction between RSPO1 R66A and ZNRF3 ECD. (C) Interaction between RSPO1 and ZNRF3 ECD P103A. ECD, extracellular domain.

Receptor-binding motifs are required for signaling

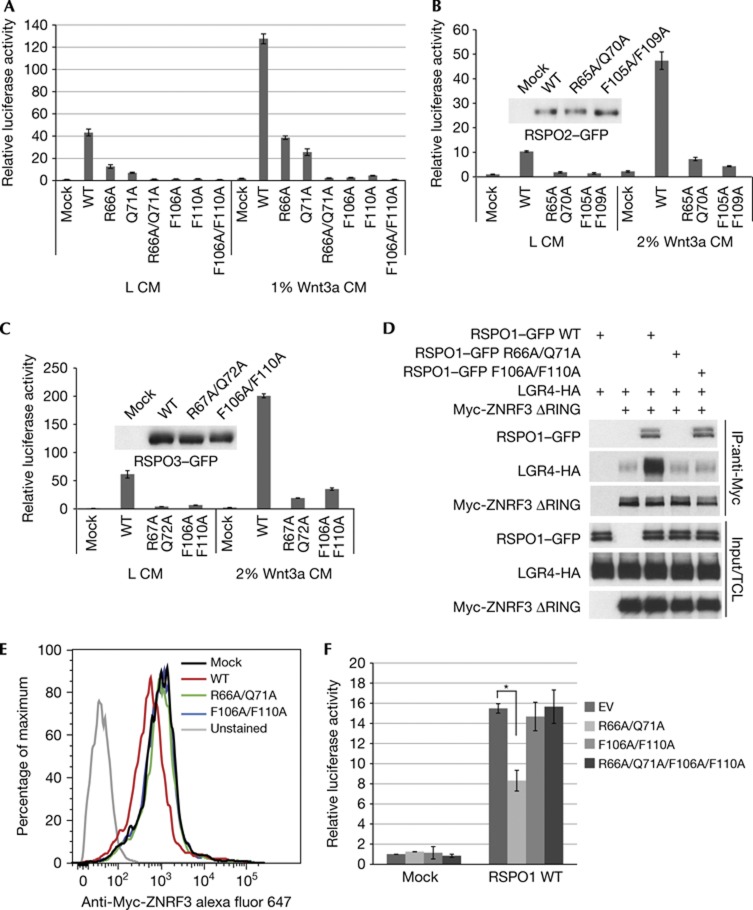

We have previously proposed that R-spondin increases Wnt signalling by binding to both LGR4 and ZNRF3, which leads to inhibition of ZNRF3 [18]. This model predicts that R-spondin needs to interact with both LGR4 and ZNRF3 at the same time to be functional. To test this hypothesis, we tested RSPO1 mutants that failed to bind to either LGR4 or ZNRF3 in SuperTopflash (STF) Wnt reporter assay in HEK293 cells. R-spondin only functions as Wnt enhancer, and its activity in HEK293 cells is completely dependent on endogenous Wnt [12]. We tested RSPO1 mutants in the HEK293–STF reporter assay with or without low dose of Wnt3a CM, and obtained similar results (Fig 3A). Both FU2 mutants (F106A or F110A), which have defective binding to LGR4, have drastically reduced signalling activity (Fig 3A). Two FU1 mutants (R66A or Q71A), which have compromised ZNRF3 binding, had significantly decreased activity, while R66A/Q71A double mutant lost its signalling activity (Fig 3A). RSPO2 and RSPO3 proteins can strongly potentiate Wnt/STF activity and share good sequence homology with RSPO1 in the furin-like domains (supplementary Fig S1 online). We hypothesized that RSPO2/3 adopt similar mechanism as RSPO1 for receptor interaction. Residues in RSPO2/3 corresponding to critical residues of RSPO1 were mutagenized to alanine. HEK293–STF cells were treated with RSPO2 or RSPO3 conditioned medium in the absence or the presence of low-dose Wnt3a. As expected, RSPO2/3 FU1 or FU2 domain double mutants exhibited significantly reduced activity (Fig 3B,C). These results indicate that both ZNRF3 and LGR4-interacting motifs of R-spondin are required for promoting Wnt signalling.

Figure 3.

Physical interaction with both LGR4 and ZNRF3 is required for the signaling activity of R-spondin. (A) RSPO1–GFP mutants with defective LGR4 or ZNRF3 binding lose Wnt-potentiating activity. HEK293–STF cells were treated with wild type or mutants of RSPO1–GFP in the presence of control conditioned medium (L CM) or 1% Wnt3a CM, and STF luciferase reporter activity was measured. Note that RSPO1 promotes the signalling activity of endogenous Wnt proteins in HEK293 cells. The same amount of RSPO1–GFP was used in the experiment. Error bars denote the s.d. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) RSPO2–GFP FU1 or FU2 double mutants have compromised Wnt-stimulating activity. The amount of wild type or mutants RSPO2–GFP was examined by anti-GFP immunoblotting. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) RSPO3–GFP FU1 or FU2 double mutants have compromised Wnt-stimulating activity. The amount of wild type or mutants RSPO3–GFP was examined by anti-GFP immunoblotting. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Wild-type but not mutant RSPO1–GFP induces the association between LGR4-HA and Myc-ZNRF3ΔRING. HEK293 cells co-expressing indicated plasmids were treated with RSPO1–GFP conditioned medium for 1 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and immunoprecipitates were resolved and blotted with indicated antibodies. (E) Wild-type but not mutant RSPO1–GFP induces membrane clearance of ZNRF3. HEK293 cells co-expressing LGR4 and Myc-ZNRF3 were treated with wild-type or mutant ZNRF3 for 24 h. The level of Myc-ZNRF3 on the cell surface was quantified by FACS. (F) RSPO1 R66A/Q71A shows dominant negative activity. HEK293–STF cells were treated with wild-type RSPO1–GFP with or without 10-fold excess of indicated RSPO1–GFP mutant. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t-test. *P<0.01. CM, conditioned medium; FU1, furin-like domain 1; FU2, furin-like domain 2; GFP, green fluorescent protein; STF, SuperTopflash.

We have previously shown that RSPO1 promotes LGR4–ZNRF3 interaction and induces membrane clearance of ZNRF3 [18]. We tested whether LGR4 and ZNRF3 binding motifs of RSPO1 are required for these activities. Although wild-type RSPO1 increased the interaction between LGR4 and ZNRF3 in a co-immunoprecipitation assay, both R66A/Q71A and F106A/F110A mutants lost this activity (Fig 3D). Also note that wild-type RSPO1 and F106A/F110A mutant, but not R66A/Q71A mutant, were co-immunoprecipitated with ZNRF3 (Fig 3D), consistent with results from cell-based binding assay (Fig 1B). We next showed that unlike wild-type RSPO1, neither R66A/Q71A nor F106A/F110A mutant reduced the membrane level of ZNRF3 in a FACS assay (Fig 3E). These results indicate that both LGR4 and ZNRF3 binding motifs are required for RSPO1-induced LGR4/ZNRF3 interaction and downregulation of ZNRF3 on the cell surface.

We next tested whether RSPO1 Furin 1 and Furin2 domain mutants interfere with the signalling activity of wild-type RSPO1. HEK293–STF cells were treated with wild-type RSPO1 in the absence or the presence of 10-fold excess of RSPO1 R66A/Q71A, F106A/F110A or R66A/Q71A/F106A/F110A mutant (Fig 3F). RSPO1 R66A/Q71A mutant, which binds to LGR4 but not ZNRF3, reproducibly decreased Wnt-promoting activity of wild-type RSPO1 (Fig 3F). The R66A/Q71A mutant most likely exerts its dominant negative activity by affecting the interaction between wild-type RSPO1 and LGR4. Consistent with this hypothesis, the R66A/Q71/F106A/F110A mutant, which would not bind to LRG4, lost this dominant negative activity (Fig 3F). Interestingly, RSPO1 F106A/F110A mutant, which binds to ZNRF3 but not LGR4, did not show dominant activity in this assay condition. This is consistent with the observation that RSPO1–ZNRF3 affinity is much lower than RSPO1–LGR4/5 affinity. Presumably, LGR4-bound RSPO1 would have easier access to ZNRF3, rendering it resistant to the dominant activity of RSPO1 F106A/F110A.

Taken together, these results indicate that both LGR4 and ZNRF3 binding motifs are required for the ability of RSPO1 for inhibiting ZNRF3 and promoting Wnt signalling.

Characterization of RSPO1 neutralizing SOMAmer

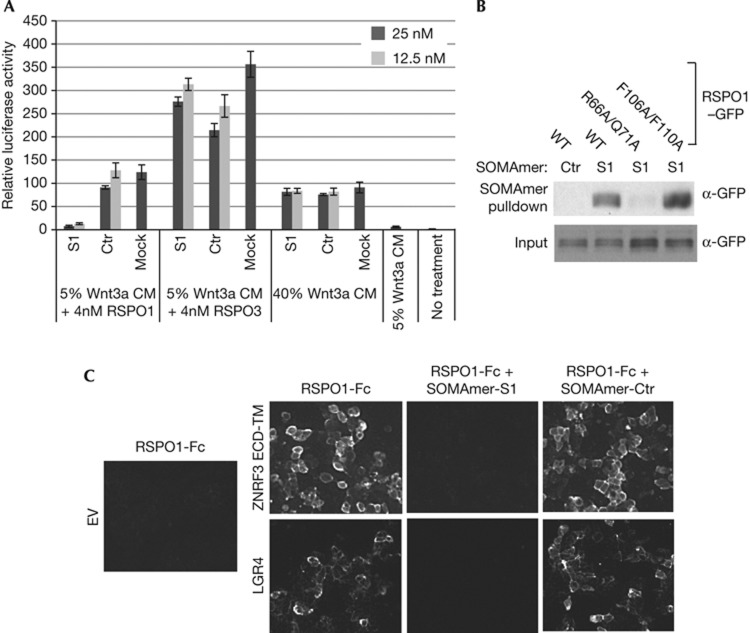

Next we utilized R-spondin neutralizing agents to further define critical elements of R-spondin. SOMAmers (slow off-rate modified aptamers) are single stranded DNA-based protein affinity reagents that incorporate chemically modified nucleotides, and SOMAmers with high affinity and specificity can be quickly generated through aptamer selection technology (SELEX) [20]. Although SOMAmers have mostly been used for biomarker studies, SOMAmers with neutralizing activities can be easily generated. One RSPO1 SOMAmer (S1) with strong neutralizing activity was identified. SOMAmer S1, but not its scrambled control (Ctr), strongly inhibited RSPO1-induced STF, without affecting RSPO3 or Wnt3a-induced STF (Fig 4A). SOMAmer S1 interacts with RSPO1 but not RSPO3 in the SPR assay (supplementary Fig S3 online). We tested whether SOMAmer S1 directly interacts with ZNRF3 or LGR4 binding motif of RSPO1 using a pull-down assay. As seen in Fig 4B, SOMAmer S1 bound to RSPO1–GFP and RSPO1 F106A/F110A–GFP, but its binding to RSPO1 R66A/Q71A–GFP was significantly reduced (Fig 4B). These results indicate that SOMAmer S1 might directly bind to ZNRF3 binding site of RSPO1 and block its interaction with ZNRF3. Indeed, SOMAmer S1 strongly inhibited the interaction between RSPO1 and ZNRF3 ECD-TM in the cell-based binding assay (Fig 4C). Interestingly, SOMAmer S1 also blocked the interaction between RSPO1 and LGR4 in the same assay (Fig 4C). This finding is not surprising, considering that SOMAmer is 18 KD, whereas FU1-FU2 is only 11KD combined. SOMAmer S1 potentially blocks RSPO1–LGR4 interaction by creating steric hindrance or inducing a conformation change of RSPO1.

Figure 4.

Characterization of RSPO1 SOMAmer. (A) RSPO1 SOMAmer specifically inhibits RSPO1-induced STF. HEK293–STF cells were treated with 4 nM RSPO1 plus 5% Wnt3a CM, 4 nM RSPO3 plus 5% Wnt3a CM or 40% Wnt3a alone, together with SOMAmer at indicated concentrations. After overnight treatment, STF luciferase activity was measured. S1, RSPO1-specific SOMAmer. Ctr, scrambled control. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) RSPO1 SOMAmer has defective binding to RSPO1 R66A/Q71A mutant. Conditioned medium of RSPO1–GFP WT, R66A/Q71A or F106A/F110A was incubated with biotinylated RSPO1-specific SOMAmer (S1) or scrambled control (Ctr). RSPO1–GFP pulled down by SOMAmers was analysed by immunoblotting using anti-GFP antibody. (C) RSPO1-specific SOMAmer blocks the interaction between RSPO1-Fc and ZNRF3 or LGR4. SOMAmer S1 or scrambled control (Ctr) was incubated with RSPO1-Fc and HEK293 cells overexpressing LGR4 or ZNRF3, and RSPO1-Fc binding to the receptors was detected by immunofluorescence microscopy. CM, conditioned medium; ECD, extracellular domain; EV, empty vector; GFP, green fluorescent protein; SOMAmer, slow off-rate modified aptamers; STF, SuperTopflash; WT, wild type.

ZNRF3 serves as the primary target of R-spondin

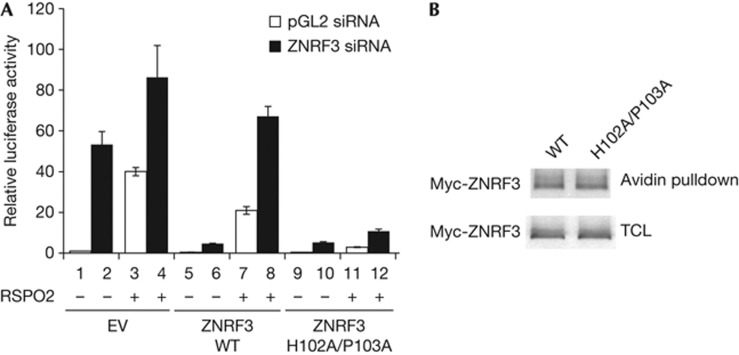

Beyond LGR4/5 and ZNRF3/RNF43, R-spondin has been reported to bind to several other proteins. The relative contribution of these R-spondin binding proteins to the signalling activity of R-spondin is not clear. We have previously shown that overexpression of ZNRF3 ECD-TM, but not a mutant with reduced binding to R-spondin, specifically blocks R-spondin-induced STF [18]. However, this experiment does not prove ZNRF3 is the functional target of R-spondin. It is conceivable that R-spondin increases Wnt signalling through binding to another protein, whiereas overexpression of ZNRF3 ECD-TM merely sequesters R-spondin from such a functional target. In addition, inability of RSPO1 R66A/Q71A to activate Wnt/β-catenin signalling does not prove ZNRF3 interaction is required for R-spondin signalling, as this mutation might disrupt another critical interaction to be identified. We reasoned that if R-spondin functions by binding and inhibiting ZNRF3, cells expressing a ZNRF3 mutant that does not bind to R-spondin should be refractory to Wnt-promoting activity of R-spondin. To eliminate the contribution of endogenous ZNRF3, we treated cells with ZNRF3 small interfering RNA (siRNA) and performed the experiment in a cDNA rescue setting. As seen in Fig 5A, treatment of HEK293 cells transfected with empty vector with ZNRF3 siRNA or RSPO2 proteins dramatically increased STF reporter (comparing bar 1 and bar 2, and bar 1 and bar 3). RSPO2 proteins slightly increased STF reporter in cells treated ZNRF3 siRNA (comparing bar 2 and bar 4), which might be due to incomplete knockdown of endogenous ZNRF3 by siRNA. ZNRF3 siRNA-induced STF can be suppressed by exogenous wild-type ZNRF3 (ZNRF3 WT) (comparing bar 2 and bar 6), indicating that exogenous ZNRF3 can replace endogenous ZNRF3 to suppress Wnt signalling. Interestingly, ZNRF3 H102A/P103A, which has defective interaction with R-spondin [18], also suppressed ZNRF3 siRNA-induced STF (comparing bar 2 and bar 10), suggesting that ZNRF3 H102A/P103A is as active as wild-type ZNRF3 in suppressing Wnt signalling. Wild-type ZNRF3-suppressed Wnt signalling can be reversed by RSPO2 protein (comparing bar 6 and bar 8), consistent with the hypothesis that the function of ZNRF3 is suppressed by R-spondin. Most importantly, the Wnt-inhibitory activity of ZNRF3 H102A/P103A is resistant to RSPO2 (comparing bar 10 and bar 12). Expression levels of wild-type ZNRF3 and ZNRF3 H102A/P103A in cell lysates or on the cell surface are indistinguishable (Fig 5B). These results indicate that ZNRF3 H102A/P103A is fully capable of inhibiting Wnt signalling, but its activity cannot be suppressed by R-spondin, presumably due to its decreased interaction with R-spondin. Together, these results strongly suggest that ZNRF3 and RNF43 are the primary targets mediating the action of R-spondin.

Figure 5.

Cells expressing ZNRF3 mutant with defective R-spondin interaction are refractory to the Wnt-stimulatory activity of R-spondin. (A) HEK293 cells were first transfected with control pGL2 siRNA or ZNRF3 siRNA to eliminate endogenous ZNRF3. Twenty-four hours after siRNA transfection, cells were transfected with empty vector (EV), Myc-ZNRF3 WT or Myc-ZNRF3 H102A/ P103A expression plasmid, and STF reporter. Twenty-four hours after plasmid transfection, all wells were treated with 5% Wnt3a and selected wells were treated with 200 ng/ml of RSPO2 proteins. STF luciferase activity was measured 24 h later. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) ZNRF3 WT and ZNRF3 H102A/P103A are expressed on the cell surface and total cell lysates (TCL) at the similar level. Cells transfected with Myc-tagged ZNRF3 WT or ZNRF3 H102A/P103A were subjected to membrane biotinylation, and biotinylated membrane proteins were pulled down with avidin beads, fractionated and blotted with anti-Myc antibody. CM, conditioned medium; ECD, extracellular domain; EV, empty vector; GFP, green fluorescent protein; siRNA, small interfering RNA; STF, SuperTopflash; TCL, total cell lysates; WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

Our study provides strong support for the bi-receptor model of R-spondin action. R-spondin increases Wnt signalling by forming a receptor complex with LGR4 and ZNRF3, which leads to inactivation of ZNRF3 and stabilization of Frizzled. In the R-spondin-LGR4–ZNRF3 complex, LGR4 serves as the engagement receptor, functioning through recruitment of R-spondin to ZNRF3. ZNRF3 serves as the effector receptor and inhibition of ZNRF3 by R-spondin potentiates Wnt signalling.

The interaction between R-spondin and ZNRF3, although weak, is specific and physiologically important. Subtle mutations in either RSPO1 or ZNRF3 can disrupt this interaction. Q71 in the FU1 domain of RSPO1 is a critical residue for RSPO1–ZNRF3 interaction. Mutation of the corresponding residue in RSPO4 (Q65R) is found in inherited anonychia [4]. The weak affinity between R-spondin and ZNRF3 can explain why LGR4 is critical for R-spondin signalling. Without LGR4, the weak interaction between R-spondin and ZNRF3 is not sufficient to bring R-spondin to ZNRF3.

The R-spondin-LGR4–ZNRF3 complex is reminiscent of the Wnt–Frizzled–LRP6 complex [21]. In the Wnt–Frizzled–LRP6 complex, Wnt binds to Frizzled and LRP6 simultaneously. LRP6 acts as the effector receptor, functioning by binding and inactivating the Axin complex. Frizzled serves as the engagement receptor, possibly functioning by recruiting Dishevelled and promoting the formation of the Wnt receptor signalosome. The R-spondin-LGR4/5–ZNRF3/RNF43 complex represents a fascinating example of a secreted protein regulating receptor turnover by targeting membrane E3 ubiquitin ligases. Furthermore, it provides us exciting opportunities of designing new therapeutic agents to block or mimic R-spondin action to treat cancer or promote tissue regeneration.

During the process of manuscript submission, a crystal structure of RSPO1–LGR5-RNF43 was published on-line [22], which shows that the Furin1 domain of RSPO1 binds to RNF43 and the Furin 2 domain of RSPO1 interacts with LGR5. Our functional studies complement perfectly with this structure study; critical residues of RSPO1 identified in our study directly interact with LGR5 or RNF43 in the crystal structure. Chen et al [22] also demonstrated a direct interaction between RSPO1 and RNF43, although the binding affinity (7–10 μM) is weaker than what we observed for RSPO1 and ZNRF3 (Kd 0.8 μM). This discrepancy is likely because of different proteins used or different methods of measurement. Several crystal structures of RSPO1–LGR4 or RSPO1–LGR5 were also published [23–25]. In these structures, beyond the Furin 2 domain, the Furin 1 domain is also involved in the interaction with LGR4/5, which we did not detect in our cell-based binding assay. This could result from different assay formats and limited assay sensitivity.

METHODS

Plasmids and proteins. Full-length or fragments of ZNRF3, RNF43 and R-spondin cDNA with corresponding protein tags were cloned with recombinant DNA techniques as previously reported [18]. Site-specific mutagenesis was performed using QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies). Recombinant ZNRF3 ECD-Fc, RSPO1-Fc and RSPO3-Fc were expressed in HEK293F cells and purified using Protein A beads (GE) followed by size exclusion chromatography over a Superdex 200 column (GE). His-tagged R-spondin1 was expressed from HEK293F cells and purified with Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow beads (GE) followed by size exclusion chromatography over a Superdex 200 column (GE). The purity of proteins is over 95%. RSPO2 and RSPO3 recombinant proteins were from R&D Systems.

Cell-based binding between RSPO1 and its receptors. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with LGR4, ZNRF3 ECD-TM or control. After 48 h of transfection, growth media was removed and cells were incubated with RSPO1–GFP conditioned media for 1 hour at 37 °C. Cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before fluorescence microscopy analysis.

Luciferase assay. STF luciferase assays were performed using BrightGlo or DualGlo Luciferase Assay kits (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. STF Luciferase reporter was transiently transfected or integrated into HEK293 cells as a read out for Wnt activity. Experiments were done with four replicates and standard deviation was calculated.

Supplementary Information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Chen, Aaron Wilson, Leon Murphy, Heinz Ruffner, Tewis Bouwmeester, Huaixiang Hao, Shaowen Wang, Neil Kubica, Lori Jennings, Scott Clarkson and Marc Kirschner for comments and advice.

Author contributions: Y.X., S.S., W.T., C.D., J.P., D.J., S.K.W., M.W., P.L., B.G., J.A.P., V.E.M, A.L. and F.C. conceived and designed the study. Y.X., R.Z., O.C., M.R., S.S., X.J., D.R., B.L., L.Q. and F.C. designed and implemented experiments. Y.X. and F.C. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Clevers H, Nusse R (2012) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149: 1192–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau WB, Snel B, Clevers HC (2012) The R-spondin protein family. Genome Biol 13: 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazanskaya O, Glinka A, del BBI, Stannek P, Niehrs C, Wu W (2004) R-Spondin2 is a secreted activator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and is required for Xenopus myogenesis. Dev Cell 7: 525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaydon DC et al. (2006) The gene encoding R-spondin 4 (RSPO4), a secreted protein implicated in Wnt signaling, is mutated in inherited anonychia. Nat Genet 38: 1245–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KA et al. (2005) Mitogenic influence of human R-spondin1 on the intestinal epithelium. Science 309: 1256–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ootani A et al. (2009) Sustained in vitro intestinal epithelial culture within a Wnt-dependent stem cell niche. Nat Med 15: 701–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodorou V, Kimm MA, Boer M, Wessels L, Theelen W, Jonkers J, Hilkens J (2007) MMTV insertional mutagenesis identifies genes, gene families and pathways involved in mammary cancer. Nat Genet 39: 759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr TK et al. (2009) A transposon-based genetic screen in mice identifies genes altered in colorectal cancer. Science 323: 1747–1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshagiri S et al. (2012) Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature 488: 660–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam JS, Turcotte TJ, Smith PF, Choi S, Yoon JK (2006) Mouse cristin/R-spondin family proteins are novel ligands for the Frizzled 8 and LRP6 receptors and activate beta-catenin-dependent gene expression. J Biol Chem 281: 13247–13257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q, Yokota C, Semenov MV, Doble B, Woodgett J, He X (2007) R-spondin1 is a high affinity ligand for LRP6 and induces LRP6 phosphorylation and beta-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem 282: 15903–15911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnerts ME et al. (2007) R-Spondin1 regulates Wnt signaling by inhibiting internalization of LRP6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 14700–14705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawara B, Glinka A, Niehrs C (2011) Rspo3 binds syndecan 4 and induces Wnt/PCP signaling via clathrin-mediated endocytosis to promote morphogenesis. Dev Cell 20: 303–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmon KS, Gong X, Lin Q, Thomas A, Liu Q (2011) R-spondins function as ligands of the orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to regulate Wnt/{beta}-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 11452–11457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau W et al. (2011) Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 476: 293–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinka A, Dolde C, Kirsch N, Huang YL, Kazanskaya O, Ingelfinger D, Boutros M, Cruciat CM, Niehrs C (2011) LGR4 and LGR5 are R-spondin receptors mediating Wnt/beta-catenin and Wnt/PCP signalling. EMBO Rep PM:2190907612: 1055–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffner H et al. (2012) R-Spondin potentiates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling through orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5. PLoS One 7: e40976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao HX et al. (2012) ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature 485: 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo BK et al. (2012) Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature 488: 665–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DR et al. (2012) Unique motifs and hydrophobic interactions shape the binding of modified DNA ligands to protein targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 19971–19976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X (2009) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell 17: 9–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PH, Chen X, Lin Z, Fang D, He X (2013) The structural basis of R-spondin recognition by LGR5 and RNF43. Genes Dev 27: 1345–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Huang B, Zhang S, Yu X, Wu W, Wang X (2013) Structural basis for R-spondin recognition by LGR4/5/6 receptors. Genes Dev 27: 1339–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Xu Y, Rajashankar KR, Robev D, Nikolov DB (2013) Crystal structures of Lgr4 and its complex with R-Spondin1. Structure PM:2389128921: 1683–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng WC, de Lau W, Forneris F, Granneman JC, Huch M, Clevers H, Gros P (2013) Structure of stem cell growth factor R-spondin 1 in complex with the ectodomain of its receptor LGR5. Cell Rep 3: 1885–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.