Abstract

Systematic investigations of the cognitive challenges in completing time diaries and measures of quality for such interviews have been lacking. To fill this gap, we analyze respondent and interviewer behaviors and interviewer-provided observations about diary quality for a computer-assisted telephone-administered time diary supplement to the U.S. Panel Study of Income Dynamics. We find that 93%-96% of sequences result in a codable answer and interviewers rarely assist respondents with comprehension. Questions about what the respondent did next and for how long appear more challenging than follow-up descriptors. Long sequences do not necessarily signal comprehension problems, but often involve interviewer utterances designed to promote conversational flow. A 6-item diary quality scale appropriately reflects respondents’ difficulties and interviewers’ assistance with comprehension, but is not correlated with conversational flow. Discussion focuses on practical recommendations for time diary studies and future research.

Keywords: Time use, survey methods, data quality

1. INTRODUCTION

Time use studies have become a fixture in the statistical data infrastructure of many countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, and much of Europe. Responses from such collections, like all surveys, are subject to measurement error – a discrepancy between respondents’ answers and the true value of the attribute in question (Tourangeau et al. 2000; Sudman et al. 1996). Answering survey questions about time use requires respondents to interpret the questions, retrieve information from memory for the appropriate reference period (whether yesterday, last week, or last month), format their response to fit given alternatives, potentially self-edit if they feel a particular answer is or is not socially desirable, and communicate their answer to the researcher.

When an interviewer is involved, as is generally the case for telephone-based and face-to-face time use collections, further complications may arise during the interaction (Houtkoop-Steenstra, 2000; Maynard, Houtkoop-Steenstra, Schaeffer, & Van der Zouwen, 2002; Suchman & Jordan, 1990). For example, in highly structured interviews, a common technique designed to minimize interviewer variation, conversational flexibility is limited so interviewers typically may not assist respondents in tasks such as interpreting questions or formatting answers (Suchman and Jordan, 1990).

Methodological studies carried out in the 1970s and 1980s helped establish the 24-hour diary, in which retrospective reports of the previous day are collected and systematically coded, as the optimal method for characterizing time use (Juster and Stafford, 1991). In particular, the method of recalling yesterday has been viewed as less prone than “stylized” reports about last week or month to common measurement errors. For instance, stylized reports are considered more cognitively demanding (requiring recall over a longer term period and potentially arithmetic) and may be subject to social desirability for some activities (e.g., religious participation, physical activity).

Although originally administered by paper and pencil, interviewer-administered diaries are increasingly common around the world, as are computer-assisted interviews (CAI). For example, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ American Time Use Study (ATUS) is conducted over the telephone by an interviewer (see Phipps and Vernon 2008). To avoid the potential pitfalls of highly standardized interviewing, the diary portion of the ATUS is conducted using “conversational” interviewing layered over a standardized instrument. This technique trains interviewers to guide respondents through memory lapses, to probe in a non-leading way for the level of detail required to code activities, and to redirect respondents who are providing unnecessary information (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012). Embedded in this approach is the assumption that relative to inflexible standardized interviews, giving interviewers discretion of what to ask and when to ask it can lead to improved data quality.

Indeed, there have been several studies suggesting that conversational interviewing can lead to better comprehension and hence higher quality responses than standardized interviewing, particularly when respondents’ circumstances are ambiguous (Conrad and Schober, 2000; Schober and Conrad 1997), as is likely to be the case in a time diary context. In these studies, conversational interviewers were able to clarify survey concepts, i.e., provide definitions, whether respondents explicitly requested help or the interviewers judged that respondents needed it. They could provide definitions verbatim or could paraphrase them. This practice was not strictly standardized in the sense that different respondents could receive different wording because the clarification dialog was not scripted. Otherwise, the wording was typically very similar between respondents.

The way respondents comprehend their task, recall events, and report about time use when completing 24-hour diaries is not well understood. However, it seems likely interviewers can help each of these processes, if they are not constrained by the need to standardize wording across respondents. Moreover, research questions squarely focused on respondent and interviewer interaction and the role of conversational techniques during the 24-hour diary collection remain largely unexplored. Consequently, questions remain about the extent of cognitive difficulty experienced by respondents and the role interviewers play in shaping the 24-hour diary.

Measures of diary quality have also been lacking, typically focusing on the number of activities reported as a measure of quality (where diaries with fewer than five activities are equated with poor quality; Alwin, 2009). A recent study of time diary quality proposed a new scale based on interviewer perceptions of respondent comprehension, engagement, and uncertainty (Freedman et al. 2012), but how these measures might be related to respondent and interviewer behaviors remains unexplored.

In this paper we analyze recordings of a random sample of 24-hour time diary interviews conducted with a subsample of the U.S. national Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). Our aim is twofold: (1) to describe respondent and interviewer behaviors and interactions during a 24-hour recall diary, paying particular attention to behaviors that may indicate difficulty with the interview and therefore likely to be related to response quality; and (2) to determine which of such behaviors are detected by interviewers in their observations used to assess diary quality.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 The Diary Interview

The Disability and Use of Time (DUST) supplement to the 2009 PSID collected time diary and supplemental information from couples in which at least one spouse was age 60 or older. Both spouses participated in two (same-day) computer-assisted telephone interviews. Response rates were 73%. For details see Freedman and Cornman (2012).

The DUST time diaries built directly upon the ATUS interview design, but replaced several of the non-standardized conversational techniques in ATUS with tailored, yet scripted, content that gave the interviews a conversational tone (Freedman et al. 2013). Respondents were asked to reconstruct the day prior to the interview, beginning at 4:00 AM. For each activity, the respondent was asked what he/she did [next] and how long the activity took, followed by a series of tailored follow-up questions, including where they were, who was with them, and how they felt (see Table 1). The interviewer entered the activity (or activities) on separate lines in open text fields, which were later coded to a detailed 3-digit coding scheme (Freedman and Cornman 2012). If more than one activity was named, the respondent was taken through a series of scripted questions to identify whether the activities were simultaneous or sequential, and if the former, the main activity.1

Table 1.

Number of Utterances by Question Type and Actor

| Utterances | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Variable name | Interviewer allowed to “ask or confirm” | Number by Respondent | Number by Interviewer | Total |

| Most activities: | |||||

| Yesterday at 4:00am, what were you doing? OR At [time] what did you do next? OR What is the next thing that you can remember doing? | ACTIVITY | N | 1746 | 2241 | 3987 |

| Until what time did you do that OR How long did that take or how long did you do that? | DURATION | N | 1529 | 2256 | 3785 |

| So you (were) [activity] from about [start time] to [end time], is that correct? | CONFIRM | N | 1116 | 1622 | 2738 |

| Where were you while you were doing that? Or Where did you (pick up / drop off) your [passenger]? | WHERE | Y1 | 565 | 896 | 1461 |

| How did you get there? | HOW | Y1 | 99 | 179 | 278 |

| Who did that with you? OR Who went with you? OR Who were you talking to? OR Who did you pick up/drop off? | WHO ACTIVE | Y2 | 758 | 1100 | 1858 |

| Who else was [at home / outdoors at home/yard / at work / there] with you? OR Who else went with you? | WHO PASSIVE | Y3 | 582 | 885 | 1467 |

| (If household or care activities:) Who did you do that for? | WHO FOR | N | 273 | 420 | 693 |

| How did you feel while you (were) [DESCRIPTION]? [(If you had more than one feeling, please tell me about the strongest one. Did you feel mostly unpleasant, mostly pleasant, or neither? | HOW FEEL | N | 1038 | 1963 | 3001 |

| If more than one activity named: | |||||

| Just to be clear, were you doing [both / all] of these activities at [time]? | SAME TIME | N | 172 | 222 | 394 |

| If doing simultaneous activity: If you had to choose, which of these would you say was the main activity? (By main activity, we mean the one that you were focused on most) | MAIN | N | 148 | 211 | 359 |

| If first activity & sleep | |||||

| We'd like to know a little more about how you slept [DAY BEFORE YESTERDAY] night. About what time did you go to sleep for the night on [DAY BEFORE YESTERDAY] | TIME BED | N | 165 | 223 | 388 |

| Did it take you more than half an hour to fall asleep? | FALL ASLEEP | N | 119 | 138 | 257 |

| Did you wake up during the night, that is between the time you fell asleep and [time woke up]? | WAKE DURING | N | 109 | 137 | 246 |

| Did you have trouble falling back to sleep? | BACK SLEEP | N | 83 | 120 | 203 |

| How would you rate your sleep? Would you say it was excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor? | RATE SLEEP | N | 111 | 179 | 290 |

| Other select follow-up questions | |||||

| (If gap between activities:) What time did you start doing that? | START TIME | N | 14 | 19 | 33 |

| (If traveling:) Were you the driver or the passenger? | DRIVER | Y | 74 | 116 | 190 |

| (If talking to someone else:) Was this on the phone or in person? | PHONE | Y | 22 | 35 | 57 |

| Total | 8723 | 12962 | 21685 | ||

The interviewer could ask or confirm for all activities except travel to pick up/drop off.

The interviewer could ask or confirm for all activities except travel to pick up/drop off and talking to someone else.

The interviewer could ask or confirm for all activities except work and socializing.

Interviewers then asked how long the (main) activity took. After keying in the type of response, duration in hours and minutes (e.g.1 hour and 15 minutes) or an exact end time for the activity (e.g. 4:00 PM), interviewers were directed to enter values accordingly.

Once a given diary entry (activity and time) was complete, the interviewer read to the respondent a semi-scripted confirmation of the activity, “So you (were) [main activity] from about [start time] to [end time], is that correct?” The respondent, in turn, could either confirm or have the interviewer correct the information.

After the correct main activity and times were entered, the interviewer then selected one of nine categories for the main activity, which determined appropriate follow-up questions (e.g. where the respondent did the activity, who did the activity with the respondent, who else was there, who they did the activity for, how they felt while doing the activity). Some follow-up questions were limited to specific types of activities. For instance, if the first activity was sleeping, respondents were asked several follow-up questions about the quality of that night's sleep. For some, but not all, of the follow-up questions interviewers were instructed (on the computer screen) that they could “Ask or Confirm” (see column 3 of Table 1). Follow-up questions about where the activity occurred and who participated allowed the interviewer to capture other responses in an open text field.

2.2 Sample and Unit of Analysis

In total, 394 couples participated. Each member of the sample was asked to complete two diaries (one weekday and one weekend day). 33 spouses were not able to participate because of a permanent health condition and a handful of respondents completed only one interview yielding in all 1,506 completed diaries obtained by 25 interviewers. The mean age of respondents was 69. Four interviews conducted by each interviewer, for a total of 100 interviews, were randomly selected. Of these, five were excluded because four were inaudible (all of those sampled for one interviewer) and one interview did not have diary quality data, leaving a total of 95 diaries for the analyses reported here.

For these 95 interviews, approximately one-third of each was recorded, on average the first 9 out of 26 activities. Transcripts of the interviews yielded 21,685 “utterances” (132-440 per diary, or 228 on average), defined as one speaker's turn in the conversation about a given diary question, and 6015 “sequences” (42-78 per diary, or 63 on average), defined as the set of utterances produced by interviewer and respondent about a question. To illustrate, the sequence below has 5 utterances:

Interviewer: So then how long did it take you to have breakfast?

Respondent: Oh, maybe 20 minutes, half an hour.

Interviewer: Which would be closer, 20 minutes or--

Respondent: Half an hour.

Interviewer: Uhhuh.

For each given activity (e.g. ate breakfast) there are at least four sequences (e.g. the activity, duration, confirmation, and any tailored follow-up questions).

2.3 Interaction coding

A coding scheme was developed by the investigators to identify respondent and interviewer verbal behaviors likely, on theoretical grounds, to be related to quality. In doing so we drew upon Ongena and Dijkstra's (2007) model of interviewer-respondent interaction. The model is structured into several distinct stages of question answering, borrowed from Tourangeau et al. (2000): question formulation, interpretation, retrieval, judgment, response formatting, and finalizing the response. For each stage and each actor in the interview (respondent, interviewer), the model highlights behaviors that may be related to quality.

Table 2 shows the mutually exclusive utterance types and non-mutually exclusive behaviors, for both interviewers and respondents, by stage of interviewer-respondent interaction. Because there is some ambiguity as to whether particular interactions reflect interpretation, retrieval, or judgment, we combine them into a single category, which we refer to as “comprehension.” An interviewer utterance reflecting potential problems with question formulation, for instance, involves departing from reading verbatim the wording on the screen. Comprehension-related behaviors by the interviewer include: offering an explanation, use of probes (What is the next thing you remember doing? Let's break that down), reminders about earlier information provided. Comprehension-related behaviors by the respondent include: providing an uncodable answer (including “other, specify” answers not on the coding frame), requests for clarification, offering an explanation, thinking aloud as a response (Umm... or Let me think...), mid-utterance pauses, fillers (e.g., um, uh), hedges (e.g., about 3 o'clock), relying on routines rather than memory of events, self correcting (no, I went to get the mail next), or reconstructing events out loud (it must have been 6 o'clock because I was watching the news). We treated interviewers’ offering response categories as evidence of a problem with response formatting. Finally, we added an additional set of behaviors reflecting the interviewer's attempt to regulate the conversational flow, e.g. interviewers filling silence (while typing answers) with repetition, offering “backchannels” that include neutral phrases (mhm hmm, I see) or gratitude (thank you), and answers to such utterances by the respondent.

Table 2.

Utterance Types and Behaviors by Actor and Stage of Respondent-Interviewer Interaction

| Coded Utterances/Behaviors by Actor |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewer | Respondent | ||||

| Question formulation | Read not verbatim (u) | ||||

| Comprehension: (Interpretation; Retrieval and Judgment) | Explanation (u) Remind R of earlier response (u) Probe (u) |

Uncodable answer (u) Request for clarification (u) Explanation (u) Thinking aloud (u) Pauses (b) Fillers (b) Hedges (b) Relying on routine (b) Self correction (b) Reconstruction (b) |

|||

| Response Formatting / Finalizing Response | Offer response options (u) | ||||

| Conversation Flow | Fill while logging (u) Repeat response (u) Back channel/gratitude (u) |

Response to repetition (u) | |||

u=mutually exclusive utterances; b=non-mutually exclusive behaviors

Coding was carried out by two trained staff members (a graduate student in survey methodology and the transcriber, an undergraduate student) using Sequence Viewer (http://www.sequenceviewer.nl/) software, which is designed specifically for investigating sequential activities, such as patterns of conversational turns. Initially, both coders were assigned the same small set of diary interviews to code. Discrepancies were discussed and reconciled before coders continued with the remaining diaries. A detailed coding sheet was developed to guide consistent decision making.

2.4 Diary quality measures

A measure of perceived diary quality was constructed based on interviewer's subjective assessments of respondent comprehension, engagement, and uncertainty in completing the diary. Such information was obtained through a set of interviewer observations collected after the interview was completed. Interviewers were asked to assess “none,” “some,” and “a lot” for how much difficulty the respondent had understanding the questions and how much probing was needed for the respondent to complete the diary. Interviewers also assessed how hard the respondent tried to provide correct answers to the diary (tried to answer all, most, some, or few/no questions correctly); how confident they seemed about the answers to the diary (very, mostly, somewhat, little or not at all); how often the respondent seemed to guess at what he/she did next (all, most, some, few, activities, or never guessed); and how often he/she guessed at how long an activity took (all, most, some, few, activities, or never guessed). We reverse coded the indicators as needed so that higher numbers reflected better quality and (following Freedman et al., 2012) summed them to form an overall score (Cronbach's alpha=.80). The diary quality measure ranged from 9 to 24 with a mean of 20.

2.5 Analytic Approach

We first tallied the number of utterances by question type and actor (respondent, interviewer). We then tabulated for interviewers and then respondents the percentage of (mutually exclusive) utterance types by question and for respondents the prevalence of various other (non-mutually exclusive) behaviors of interest mentioned above. We also characterized the sequence by calculating its complete length and whether it was a long sequence (with five or more utterances). Because these sequence-level measures include conversational flow in addition to utterances designed to elicit answers from respondents, we also calculated for each sequence the number of utterances it took for a codable answer to first be given and whether a codable answer was given anywhere in the sequence. We also identified the typical (most common) patterns of interviewer-respondent interactions by sequence length. We expect to see patterns by type of question that highlight the more challenging nature of recalling activities and times relative to recalling other details about an activity.

Finally, we examined the relationship between respondent-interviewer interactions and diary quality. To do so we first summarized the utterances and behavior data to the diary level, calculating the percentage of actor utterances in a given diary for each mutually exclusive utterance type and for each (non-mutually exclusive) behavior type. We also calculated the mean sequence length per diary, the mean utterance by which a codable answer was obtained, and the percentage of sequences in each diary with no codable answer. We then examined correlations between each of these measures and each diary quality component as well as the overall diary quality scale. We anticipated that behaviors indicative of problems with question comprehension would be reflected in interviewers’ perceptions about diary quality. In contrast, we hypothesized that interviewers would not reflect in diary quality measures their own behaviors in formulating questions or response categories or behaviors related to conversational flow.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Interviewer Utterances

Across all types of questions, the majority of interviewer utterances involved question formulation (42% verbatim utterances where the interviewer read exactly what was on the screen and 7% departures from verbatim), and 85% of all question formulations were verbatim (42%/49%). Also common were utterances related to conversational flow (27% backchannels or expressions of gratitude, 10% repeating responses aloud, and 2% fills while logging answers). Far fewer utterances involved assistance with comprehension (1% offers of explanation; 2% probes) and answer formulation (6% offers of categories).

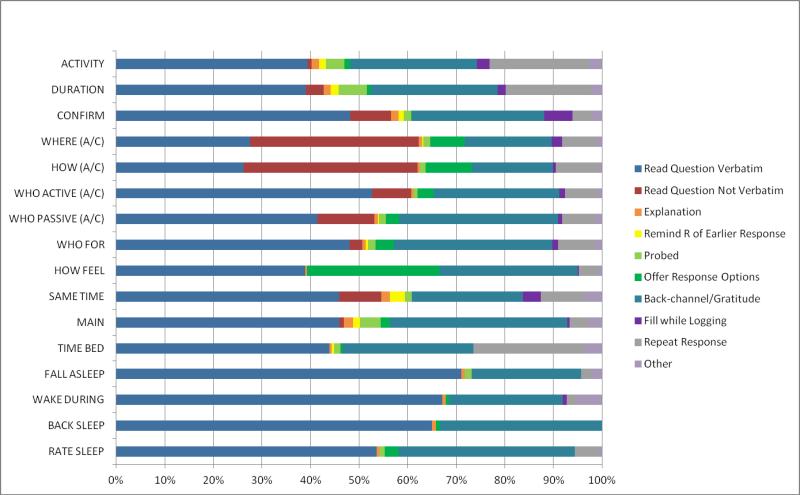

Differences in interviewer utterances by question type are highlighted in Figure 1. Four points are noteworthy. First, departures from reading the question verbatim (shown in red in Figure 1) were most apparent for the questions where interviews were allowed to either ask or confirm (where, how, who was actively engaged in the activity with the respondent, and who else was there). Interviewers also departed from verbatim when they asked about activities that occurred at the “same time” and at the confirmation screen, possibly indicating respondents did not always find the repetition necessary.

Figure 1.

Respondent Utterances by Question Type

Second, interviewer behaviors that indicated assistance with comprehension were rare (<2%) across all question types, with only a few exceptions: probes constituted 6% of utterances about the length of an activity, 4% about the activity2, and 4% about which was the main activity. These finding suggest these three questions may be somewhat more cognitively challenging—at least for some respondents—than the rest of the items in the interview.

Third, with respect to response formatting, interviewers offered response options most often for the item on how the respondent felt (27% of utterances). We attribute this finding to the break between question and closed response categories (How did you feel while you were <doing activity>? Did you feel mostly unpleasant, mostly pleasant, or neither?), which allowed respondents to interject the answer “fine” in between. Interviewers also offered response categories in nearly 10% of utterances about where they were and 7% of utterances about how they got there, both of which had relatively long lists of potential choices that were not intended to be read.

Fourth, although backchanneling and gratitude constituted a high proportion of utterances across all questions (ranging from 17%-36%), repetition of answers was most common for questions about activities and duration-related questions (including the time the respondent went to bed the night before). It may be that the complexity of these questions led interviewers to repeat information; the activity questions involved recording open text while the latter involved multiple screens to record time (first whether exact time or duration, and then hours and minutes).

3.2 Respondent Utterances and Behaviors

Across all types of questions, the majority of respondent utterances (68%) involved codable answers. Far fewer utterances involved utterances related to interpretation difficulties or retrieval and judgment: 10% of utterances were (initially) uncodable answers, 3% involved requests for clarification, and less than 2% thinking. Another 6% of utterances involved conversational flow (response to an interviewer's repetition).

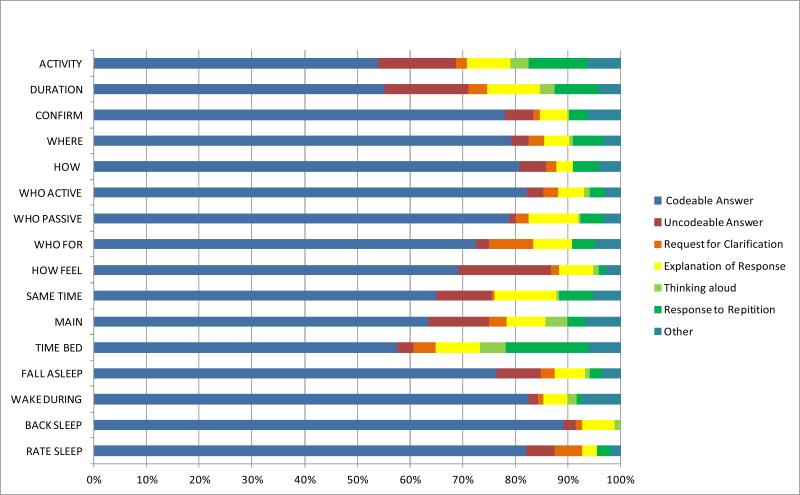

Differences in respondent utterances by question type are highlighted in Figure 2. As anticipated, comprehension-related utterances (uncodable answer, request for clarification, and explanation, shown in red, orange, and yellow) were most evident for activity (25% of utterances) and duration questions (30% of utterances). Respondents also appeared to have difficulty with questions about whether activities were done at the same time (23% of utterances) and selecting the main activity (22% of utterances), and as previously mentioned they often offer uncodable answers to the close-ended question asking how they felt (18% of utterances).

Figure 2.

Respondent Utterances by Question Type

Table 3 shows additional respondent behaviors indicative of comprehension challenges by question type. Overall, fillers (14%) and hedges (15%) were most prevalent, followed by pauses (7%). In contrast, reliance on routine (2%), self-correction (2%), and reconstructing events out loud (1%) were rarely heard. Pauses and fillers were most common for questions about what was done next (activity), for the time they went to bed, selection of main activity, and duration of activity. Hedges were most common for duration of activity (46%) and time went to bed (42%). These finding suggest that rather than relying on routine, respondents in this corpus attempted to retrieve information from memory, although the high frequency of hedging about duration suggests times being reported may be better interpreted as approximate rather than exact.

Table 3.

Additional Respondent Behaviors by Question Type (%)

| Question Type | Pauses | Fillers | Hedges | Rely on Routine | Self Correct | Reconstructs Events | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTIVITY | 12.4 | 25.1 | 11.6 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1746 |

| DURATION | 8.7 | 18.7 | 46.4 | 4.6 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 1529 |

| CONFIRM | 2.0 | 2.9 | 13.3 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 0.2 | 1116 |

| WHERE | 1.8 | 5.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 565 |

| HOW | 0.0 | 6.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 99 |

| WHO ACTIVE | 3.3 | 10.8 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 758 |

| WHO PASSIVE | 1.9 | 9.6 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 582 |

| WHO FOR | 4.0 | 12.1 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 273 |

| HOW FEEL | 6.1 | 11.4 | 8.8 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 1038 |

| SAME TIME | 5.2 | 12.2 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 172 |

| MAIN | 11.5 | 20.3 | 16.2 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 148 |

| TIME BED | 12.7 | 24.2 | 42.4 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 165 |

| FALL ASLEEP | 5.0 | 12.6 | 14.3 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 119 |

| WAKE DURING | 4.6 | 11.9 | 9.2 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 109 |

| BACK SLEEP | 9.6 | 10.8 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 83 |

| RATE SLEEP | 6.3 | 11.7 | 18.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 111 |

| ALL | 6.5 | 14.1 | 15.6 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 8723 |

3.3 Patterns Within Sequences

Across all 6,015 sequences, the average sequence length was 3.4 utterances, 20% of sequences consisted of 5 or more utterances, and 93% of sequences had at least one utterance that was a codable answer, obtained on average after 2.4 utterances.

As shown in Table 4, sequences were longer on average for questions about the activity (4.6), its duration (4.3), time went to bed (4.3), how the respondent felt (4.1), the main activity (3.9) and whether activities that were reported occurred at the same time (3.8). The percentage of sequences with five or more utterances was highest for questions about activity and duration (36% and 32%, respectively).

Table 4.

Mean Number of Utterances Per Sequence by Question Type

| Question Type | Number of Sequences | Mean number of utterances per sequence | % with 5+ utterances | Mean utterances until codable answer | % no codable answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTIVITY | 868 | 4.6 | 36.3 | 2.4 | 3.9 |

| DURATION | 876 | 4.3 | 32.3 | 2.7 | 9.8 |

| CONFIRM | 862 | 3.2 | 13.1 | 2.1 | 4.2 |

| WHERE | 542 | 2.7 | 10.5 | 2.3 | 19.4 |

| HOW | 111 | 2.5 | 10.8 | 2.3 | 28.8 |

| WHO ACTIVE | 634 | 2.9 | 10.7 | 2.2 | 4.4 |

| WHO PASSIVE | 440 | 3.3 | 15.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| WHO FOR | 197 | 3.5 | 18.8 | 2.3 | 5.1 |

| HOW FEEL | 740 | 4.1 | 25.3 | 2.8 | 4.6 |

| SAME TIME | 105 | 3.8 | 21.0 | 2.4 | 4.8 |

| MAIN | 92 | 3.9 | 22.8 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| TIME BED | 91 | 4.3 | 26.4 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| FALL ASLEEP | 91 | 2.8 | 12.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| WAKE DURING | 91 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| BACK SLEEP | 74 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 2.1 | 0.0 |

| RATE SLEEP | 89 | 3.3 | 13.5 | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| ALL | 6015 | 3.4 | 19.6 | 2.4 | 6.7 |

The average number of utterances to obtain a codable answer ranged from 2.1 to 2.8, with longer than average sequences for questions about the activity, its duration, how the respondent felt, and the main activity. The percentage of sequences with no codable answer was highest for where and how, both of which allowed interviewers to capture “other, specify” (considered for this exercise as not codable).

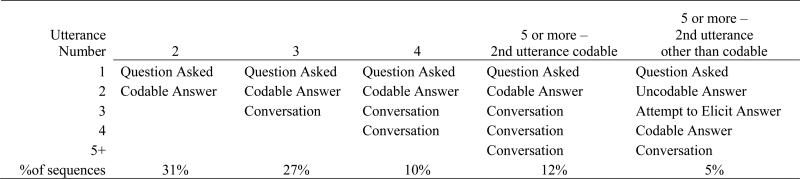

Common sequence structures by number of utterances are illustrated in Figure 3. Regardless of the question type, exchanges between interviewer and respondent in sequences made up of four or fewer utterances largely followed the same structure. For three utterance sequences, for example, an interviewer's question was typically followed by a codable answer from the respondent, which was then followed by an interviewer backchannel or expression of gratitude. In sequences with four utterances, the typical pattern involved asking the question, providing a codable answer, followed by conversational exchanges such as repeating the respondent's answer, backchannel or expression of gratitude, or a respondent's reply to the interviewer's repetition.

Figure 3.

Common Interviewer-Respondent Interactions by Sequence Length

Among longer sequences (containing five or more utterances; approximately 20% of sequences), two dominant patterns emerged. In one pattern, the interviewer asked a question, the respondent gave a codable answer, and remaining utterances involved interviewer's repetition or gratitude and the respondent's reply to these conversational elements. In the second pattern, the interviewer asked the question, the respondent's utterance reflected difficulty with interpretation or retrieval/judgment (e.g., uncodable answer, request for clarification, explanation, or thinking aloud) and the interviewer attempted to elicit a correct response (e.g. by probing, explaining, repeating the question). After a codable answer was obtained, more conversation typically ensued with the interviewer repeating or expressing gratitude and the respondent sometimes replying to these utterances.

3.4 Relationship to Perceived Diary Quality

Select behaviors reflecting comprehension difficulties were correlated with perceived overall diary quality scores (Table 5). In particular, diaries with a greater percentage of uncodable answers, explanations, and hedging by respondents had lower overall quality scores. Diaries with higher percentages of reminders to respondents of earlier responses and probing by interviewers also had lower overall quality scores.

Table 5.

Bivariate correlations between diary quality measures and respondent and interviewer behaviors (n=95)

| Stage | How much difficulty understanding? (1-3) | Amount of probing needed (1-3) | How hard R tried (1-4) | How confident R was with answers (1-4) | How often R guessed at next activity (1-5) | How often R guessed at duration (1-5) | Summary Score (9-24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent behaviors | ||||||||

| Uncodable Answer | Comprehension | −0.24 * | −0.24 * | −0.25 * | −0.30 ** | −0.32 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.41 ** |

| Request for Clarification | Comprehension | −0.30 ** | −0.13 | −0.13 | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.14 |

| Rely on routine | Comprehension | −0.11 | −0.19 | −0.04 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.19 | −0.16 |

| Explanation of Response | Comprehension | −0.25 * | −0.20 * | −0.13 | −0.21 * | −0.17 | −0.25 * | −0.28 ** |

| Thinking aloud | Comprehension | −0.17 | 0.12 | 0.12 | −0.07 | −0.19 | −0.17 | −0.10 |

| Pauses | Comprehension | −0.09 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.14 | −0.15 |

| Fillers | Comprehension | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Hedges | Comprehension | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.33 ** | −0.40 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.33 ** |

| Self correct | Comprehension | −0.20 | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.12 | −0.20 * | −0.25 * | −0.19 |

| Reconstruct events | Comprehension | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.18 | −0.15 | −0.25 * | −0.17 |

| Response to Repetition | Conv. Flow | 0.07 | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Interviewer behaviors | ||||||||

| Read (non A/C) Question Not | Question | |||||||

| Verbatim | Formulation | 0.09 | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.09 |

| Explanation | Comprehension | −0.16 | −0.20 * | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −0.04 |

| Remind R of Earlier Response | Comprehension | −0.22 * | −0.16 | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.21 * | −0.21 * |

| Probed | Comprehension | −0.29 ** | −0.22 * | −0.19 | −0.16 | −0.08 | −0.14 | −0.23 * |

| Offer Response Options | Response | 0.06 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Fill while Logging | Conv. Flow | −0.06 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Repeat Response | Conv. Flow | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Back-channel/Gratitude | Conv. Flow | −0.25 ** | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.24 ** | −0.18 |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Mean number of utter. per sequence | −0.38 ** | −0.21 * | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.17 | −0.31 ** | −0.26 ** | |

| % of sequences with >5 utterances | −0.39 ** | −0.23 * | −0.12 | −0.15 | −0.25 * | −0.34 ** | −0.34 ** | |

| Mean utterances until codable answer | −0.13 | −0.21 * | −0.15 | −0.18 | −0.27 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.29 ** | |

| Mean seq. with no codable answer | −0.05 | −0.17 | −0.13 | −0.17 | −0.25 * | −0.23 * | −0.25 * | |

| Mean score: | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 20.1 | |

p<0.05

p<0.01

Most behaviors reflecting conversation flow alone were not picked up in perceived diary quality evaluations, with one exception. Higher rates of backchanneling and expressions of gratitude by interviewers were associated with lower ratings of respondent understanding and more guessing at activity durations. However, these associations were not strong enough to be reflected in final overall score.

All four indicators of longer sequences were associated with the overall diary quality scores. However, the indicator of sequences with 5+ utterances had the strongest correlation with overall score, and was significantly correlated with four of the six components: having difficulty, probing, guessing at activity and guessing at duration.

4. DISCUSSION

This analysis is the first we know of to systematically describe interviewer-respondent interactions in the context of a time diary and relate them to a new measure of perceived time diary quality. Several findings emerged.

First, evaluation of utterance types and sequences suggests that most time diary questions are answerable by respondents. 93% of all sequences successfully elicited a codable answer and the figure is closer to 96% if “other, specify” responses are considered codable. Only 3% of interviewer utterances and about 15% of respondent utterances signaled potential issues with comprehension (i.e. interpretation, retrieval, or judgment).

Second, consistent with our expectations, questions about what the respondent did next and how long the activity took appeared to be most cognitively challenging for respondents. Respondents signaled uncertainty (Clark and Fox Tree 2002, Schober and Bloom 2004) in responses about what they did next with fillers (um, uh) and about how long it took with hedges (about...), but they did not frequently rely on routine or self-correction, nor did they reconstruct activities aloud. These findings suggest respondents generally try to recall details from the last 24 hours.

Third, time diary questions elicit conversation, even when questions are largely scripted, the purpose of which appears to be to promote the flow of the interview. In our analysis of diary interactions, 40% of interviewer utterances involved backchannels, expressions of gratitude, repeating responses aloud, and filling silence while logging answers and 6% of respondent utterances involved responses to interviewers’ repetition. Consequently, unlike more highly scripted interviews, longer than average sequences did not necessarily indicate respondent difficulty with diary questions.

Finally, we provided evidence that a set of six interviewer-provided observations about diary quality appear to appropriately reflect respondents’ difficulties with and interviewers’ assistance with comprehension. Furthermore, these judgments are not correlated with utterances that simply reflect conversation flow, a finding that further buttresses the validity of the proposed scale.

This study has several important limitations. The DUST diary application is unique in that it purposefully attempted to script, in a flexible way, portions of the questionnaire that in other studies have been left to interviewers to sort out. For instance, unlike ATUS, the DUST diary application has screens that help determine whether activities are sequential or simultaneous. The DUST diary is also purposefully conversational in tone, offering interviewers flexible phrases like “So you (were) [activity] from about [start time] to [end time], is that correct?” It may be that these phrases encourage more conversation than other applications. Notwithstanding these unique features, in other ways, DUST mimics ATUS and other diary applications much more closely; for example, questions about activity, duration, and where/how are standard features of most time diary studies.

An additional limitation is that only a portion of the diary interview was recorded and transcribed. In all cases the first third or so of the interview was recorded – approximately 9 activities out of 26 on average. It may be that respondents learn as they cycle through the interview and that subsequent parts of the interview are less challenging than earlier parts. Future research on this topic would benefit from recording the entire interview and examining utterances by activity number.

Moreover, the DUST sample is limited to older adults, whose mean age was nearly 70, and thus generalizability to all adults is limited. It is not obvious how this limitation influences findings. Given that older adults are likely to have more memory problems than younger adults, this sample may over-represent difficulties with daily diaries. At the same, time, older adults may have fewer time commitments than younger individuals and therefore may be more prone to engage in conversation than their younger counterparts. Future research on time diaries would benefit from widening the age range for evaluations of respondent-interviewer interactions.

Despite these limitations, our analysis suggests several key lessons relevant for future applications and research. One practical finding is that the new measures of diary quality included in DUST appear to capture behaviors and interactions that reflect real problems with diary administration. Since these items are easy to obtain, it may be worthwhile to replicate on other time diary studies in the US and around the world. If such relationships are replicated in other countries, comparisons of quality could be made for the first time using a metric other than number of activities.

Our study also raises potentially important questions relevant to theoretical research on interviewer-respondent interactions. The model advanced by Ongena and Dijkstra's (2007) highlights 5 distinct stages of interaction (question formulation, interpretation, retrieval and judgment, response formatting, and finalizing the response), but we found that, in the case of time diaries, a sixth category indicating behaviors related to conversational flow may be useful. Such behaviors include repeating information out loud, filling while logging, and backchanneling or offering gratitude.

Why the time diary elicited from interviewers relatively high levels of utterances designed to foster conversation flow (40% of interviewer utterances) is not clear. It may be that the complexity of particular questions led interviewers to repeat information aloud; such a hypothesis would be useful to investigate in future studies. On a more practical level, whether these utterances should be discouraged or encouraged is also not yet clear. We found that such behaviors are not significantly associated with the diary quality measures proposed here. However, we cannot rule out that such behaviors may contribute positively to interview quality in other ways (e.g. by building rapport, filling what would otherwise be awkward silence, or providing the respondent with an opportunity to correct information). Whether such behaviors simply lengthen the interview or provide additional benefit is an important next question.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was funded by grants P30-AG024928 and P01-AG029409 from the US National Institute on Aging. The views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not reflect those of the University of Michigan or the funding agency. During the preparation of this research, Dr. Broome was a graduate student at the University of Michigan.

Footnotes

Interviewers also were given the option of using two scripted probes (available to the interviewers on laminated cards for ease of use) to guide respondents in a non-leading way for the level of detail required to code activities: “Let's break that down” if not detailed enough (such as I worked or I cleaned up) and “To do what?” if too detailed (such as I got up, I went upstairs).

When probing about activities, interviewers used the scripted probes 62% of the time and their own probes 38% of the time.

Contributor Information

Vicki A. Freedman, University of Michigan Institute for Social Research 426 Thompson Street Ann Arbor, MI 48104, United States

Jessica Broome, Jessica Broome Research Detroit, MI, United States jessica@jessicabroomeresearch.com

Frederick Conrad, University of Michigan Institute for Social Research 426 Thompson Street Ann Arbor, MI 48104, United States fconrad@umich.edu

Jennifer C. Cornman, Jennifer Cornman Consulting Granville, OH, United States jencornman@gmail.com

REFERENCES

- Alwin DF. Assessing the Quality of Timeline and Event History Data in Calendar and Time Diary Methods in Life Course Research. In: Belli Robert F, Stafford Franck P., Alwin Duane F., editors. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. pp. 277–301. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics American Time Use Survey’s User Guide. Accessed October. 2012;27:2012. http://www.bls.gov/tus/atususersguide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad FG, Schober MF. Clarifying question meaning in a household telephone survey. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2000;64:1–28. doi: 10.1086/316757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra W. Transcribing, coding, and analyzing verbal interactions in survey interviews. In: Maynard DW, Houtkoop-Steenstra H, Schaeffer NC, van der Zouwen J, editors. Standardization and tacit knowledge: Interaction and practice in the survey interview. Wiley; New York: 2002. pp. 401–425. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Stafford F, Conrad F, Schwarz N, Cornman J. Time Together: An Assessment of Diary Quality For Older Couples. Annals of Economics and Statistics. 2012;105-106:271–289. January-June 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Stafford F, Schwarz N, Conrad F. Measuring Time Use of Older Couples: Lessons from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Field Methods. 2013;25(2) doi: 10.1177/1525822X12467142. doi:10.1177/1525822X12467142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Cornman JC. Panel Study of Income Dynamics Disability and Use of Time Supplement: User's Guide. The University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; Mar, 2012. p. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Houtkoup-Steenstra H. Interaction and the standardized interview: The living questionnaire. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Juster T, Stafford F. The Allocation of Time: Empirical Findings, Behavioral Models, and Problems of Measurement. Journal of Economic Literature. 1991;29:471–522. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard DW, Houtkoup-Steenstra H, Schaeffer NC, van der Zouwen J. Standardization and Tacit Knowledge. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ongena YP, Dijkstra W. Methods of behavior coding of survey interviews. Journal of Official Statistics. 2006;22:419–451. [Google Scholar]

- Ongena YP, Dijkstra W. A Model of Cognitive Processes and Conversational Principles in Survey Interview Interaction. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 2007;21:145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Phipps P, Vernon M. 24 Hours: An Overview of the Recall Diary Method and Data Quality in the American Time Use Survey. In: Belli Robert F., Stafford Frank P., Alwin Duane F., editors. Calendar and Time Diary Methods in Life Course Research. Sage; Thousands Oaks, CA: 2008. p. 2008. Expected Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Schober MF, Conrad FG. Does conversational interviewing reduce survey measurement error? Public Opinion Quarterly. 1997;61:576–602. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman L, Jordan B. Interactional troubles in face-to-face survey interviews. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1990;85:232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sudman S, Bradburn N, Schwarz N. Thinking about answers: The Application of cognitive processes to survey methodology. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Touranageau R, Rips L, Rasinski K. The Psychology of Survey Response. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]