Abstract

As the incidence of depression increases, depression continues to inflict additional suffering to individuals and societies and better therapies are needed. Based on magnetic resonance spectroscopy and laboratory findings, gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) may be intimately involved in the pathophysiology of depression. The isoelectric point of GABA (pI = 7.3) closely approximates the pH of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). This may not be a trivial observation as it may explain preliminary spectrophotometric, enzymatic, and HPLC data that monoamine oxidase (MAO) deaminates GABA. Although MAO is known to deaminate substrates such as catecholamines, indoleamines, and long chain aliphatic amines all of which contain a lipophilic moiety, there is very good evidence to predict that a low concentration of a very lipophilic microspecies of GABA is present when GABA pI = pH as in the CSF. Inhibiting deamination of this microspecies of GABA could explain the well-established successful treatment of refractory depression with MAO inhibitors (MAOI) when other antidepressants that target exclusively levels of monoamines fail. If further experimental work can confirm these preliminary findings, physicians may consider revisiting the use of MAOI for the treatment of non-intractable depression because the potential benefits of increasing GABA as well as the monoamines may outweigh the risks associated with MAOI therapy.

Keywords: monoamine oxidase, depression, GABA

Introduction

In the 1950s, the amine hypothesis of depression was proposed after it was observed that patients treated for hypertension with reserpine developed depression.1 Since that time, pharmacologic therapy for treatment of depression has focused on increasing concentrations of brain monoamines, namely norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine.

These neurotransmitters are present at an average concentration of 10−9 mol/kg vs. 10−6 mol/kg for gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate.2 With such low concentrations, the monoamines may serve as fine tuners for the predominant GABA/glutamate neurotransmitters.

Evidence that GABA is Important in the Diagnosis and Possible Treatment of Depression

The concept that deficiencies of GABA may contribute to depression is not new and has been proposed in the literature.2,3 GABA has been shown to release monoamines in animal models.4

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of selected voxels of brain images particularly in the occipital, frontal, and anterior cingulate cortex clearly supports the concept that tissue GABA is decreased in depression.3,5,6

In animal models, phenelzine, an inhibitor and substrate of monoamine oxidase (MAO), elevates cortical GABA levels.7,8 This effect is other than or in addition to inhibition of GABA transaminase (GABA-T).7,8

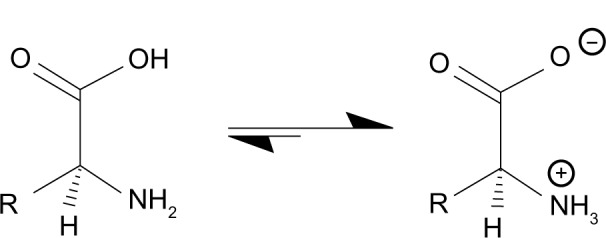

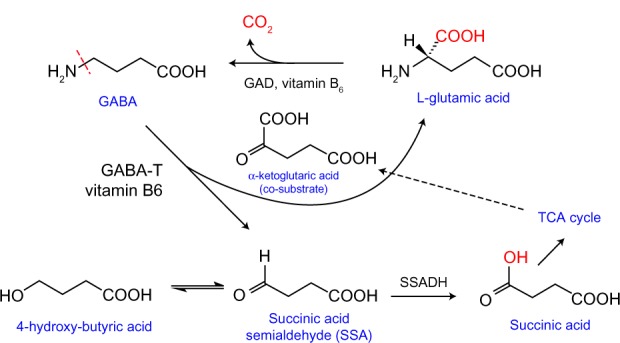

Finally, this paper proposes that MAO deamination of GABA may occur as a secondary pathway for its catabolism. MAO binds preferentially to substrates that contain lipophilic moieties such as aromatic groups or long straight chain aliphatic amines.9 Because MAO catalyzes deamination of some aliphatic amines, it seems quite plausible that it could catalyze deamination of a lipophilic form of GABA.9,10 Deamination of GABA by MAO may occur in vivo because the isoelectric point (pI) of GABA (7.3) is very close to the pH of human cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) (7.28–7.32).11,12 This may not be a trivial observation as the non-charged microspecies of GABA in the CSF may be very lipophilic based on reported studies of niflumic acid in an environment where pI = pH.13 If this relationship is true for GABA, the non-charged lipophilic microspecies may be a suitable substrate for MAO. Figure 1 illustrates the generic of this equilibrium. Thus, deamination of GABA may not only be catalyzed by GABA-T (Fig. 2) but also in small quantities by MAO. This could account for the clinical observation that MAO inhibitors (MAOI) are effective antidepressant medications for the most refractory depressions especially when selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) have failed.14

Figure 1.

Near the isoelectric point of an amino acid such as GABA, a very lipophilic form exists.

Note: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zwitterion, Zwitterion – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Figure 2.

GABA metabolism. Revised with permission from Dr. Matthias C. Lu, Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy.

Methods

Preliminary experimental data to support deamination of GABA by MAO.

1. Spectrophotometric evidence of GABA deamination by MAO-A

Determination of an absorption (Ab) curve for GABA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)

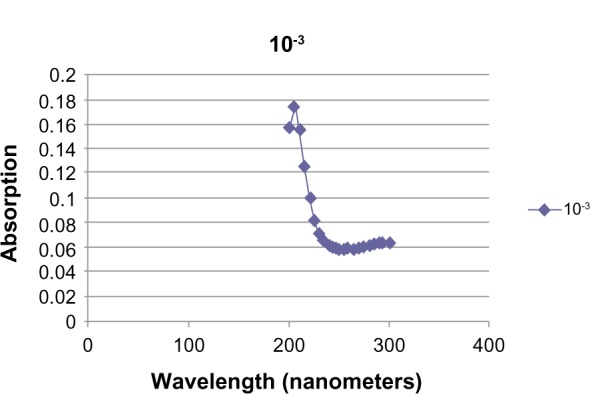

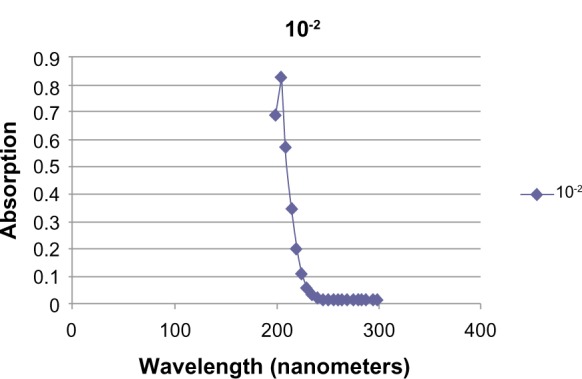

The deuterium lamp output on a Pharmacia Ultrospec III spectrophotometer was stabilized after 45 minutes. Solutions of PBS and PBS with GABA (total volume 1.04 mL) at concentrations of 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5 mmol/mL were added to quartz cuvettes. The cuvettes were gently tapped to displace any bubbles. Ab data were recorded at 5-nm intervals from 200 to 800 nm, and reference was set at each new wavelength using the PBS blank. Peak Ab at 205 nm was observed in the 10−2 and 10−3 solutions (Figs. 3 and 4). This far UV Ab peak approximated a published UV Ab of GABA on thin layer chromatography.15

Figure 3.

UV Ab of 10−3 M GABA.

Figure 4.

UV Ab of 10−2 M GABA.

Spectrophotometric deamination of GABA by MAO-A

After incubation of GABA and PBS controls at 37 °C, 5 and 10 μL of MAO-A (Sigma product number M7316, 5 mg protein/mL)) was added to the cuvettes except for the PBS blank, and the samples were incubated for an additional 30 minutes at 37 °C. Ab measured at 205 nm and ΔAb (Ab final – Ab initial) corrected for MAO-A Ab (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Decrease in GABA absorption with 5 μL MAO-A.

| SAMPLE | INITIAL ABSORPTION | INITIAL ABSORPTION CORRECTED | FINAL ABSORPTION | Δ ABSORPTION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | −0.37 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| 10−2M GABA | 0.83 | 1.27 | 0.98 | −0.29 |

| 10−3M GABA | 0.08 | 0.37 | 0.27 | −0.10 |

| 10−4M GABA | −0.01 | 0.28 | 0.20 | −0.08 |

Table 2.

Decrease in GABA Ab with 10 μL MAO-A.

| SAMPLE | INITIAL ABSORPTION | INITIAL ABSORPTION CORRECTED | FINAL ABSORPTION | Δ ABSORPTION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | 0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 10−2M GABA | 1.23 | 2.23 | 2.51 | 0.28 |

| 10−3M GABA | 0.43 | 2.43 | 2.29 | −0.14 |

| 10−4M GABA | 0.27 | 2.27 | 2.23 | −0.04 |

2. GABA reacts with MAO-A to produce ammonia

GABA incubated with MAO-A produces ammonia

Samples of PBS, PBS + MAO-A, PBS + MAO-A + GABA, and PBS + MAO-A + serotonin were assayed for ammonia. A total of 5 mL of each sample was incubated at 35 °C for two hours and agitated every 30 minutes. The samples were frozen at −10 °C overnight and then defrosted, placed in lithium heparin tubes, and analyzed for ammonia using a Siemens Dimension Vista Analyzer in the clinical chemistry laboratory of the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incubation of 10−1 M GABA with MAO-A produces ammonia.

| SAMPLE | MAO-A | GABA mol/L | SEROTONIN mol/L | AMMONIA μmol/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1. PBS | – | – | – | <25 |

| #2. PBS | 20 μL | – | – | <25 |

| #3. PBS | 50 μL | 10−2 | – | <25 |

| #4. PBS | 50 μL | 10−1 | – | 302 |

| #5. PBS | 20 μL | – | 10−2 | 185 |

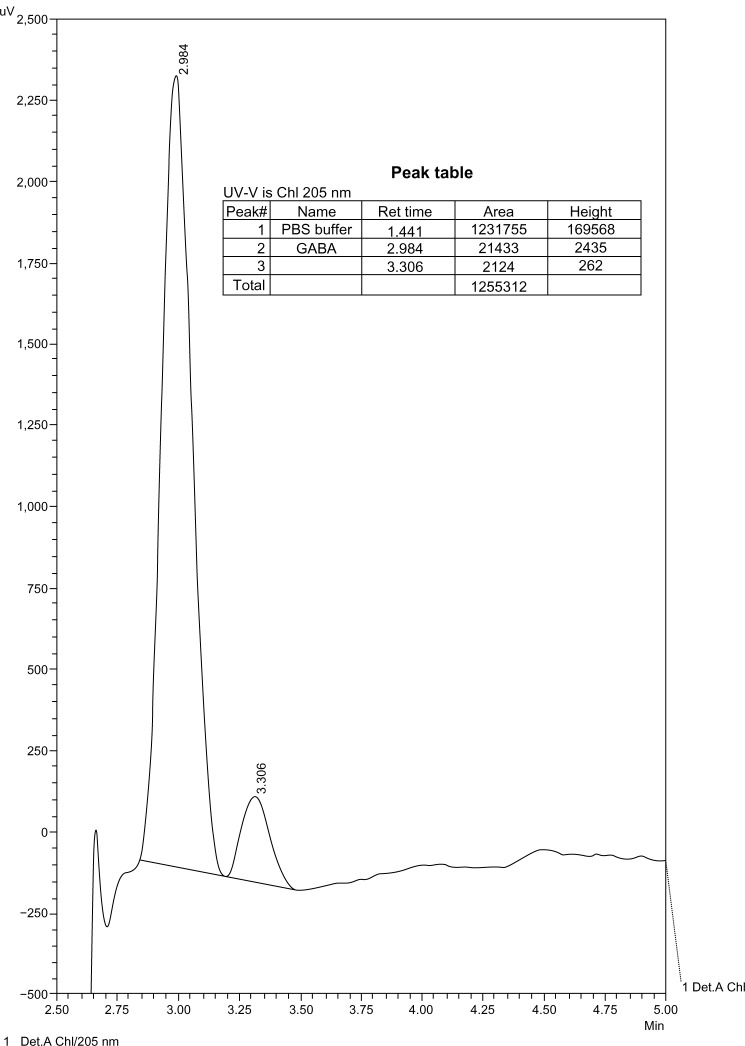

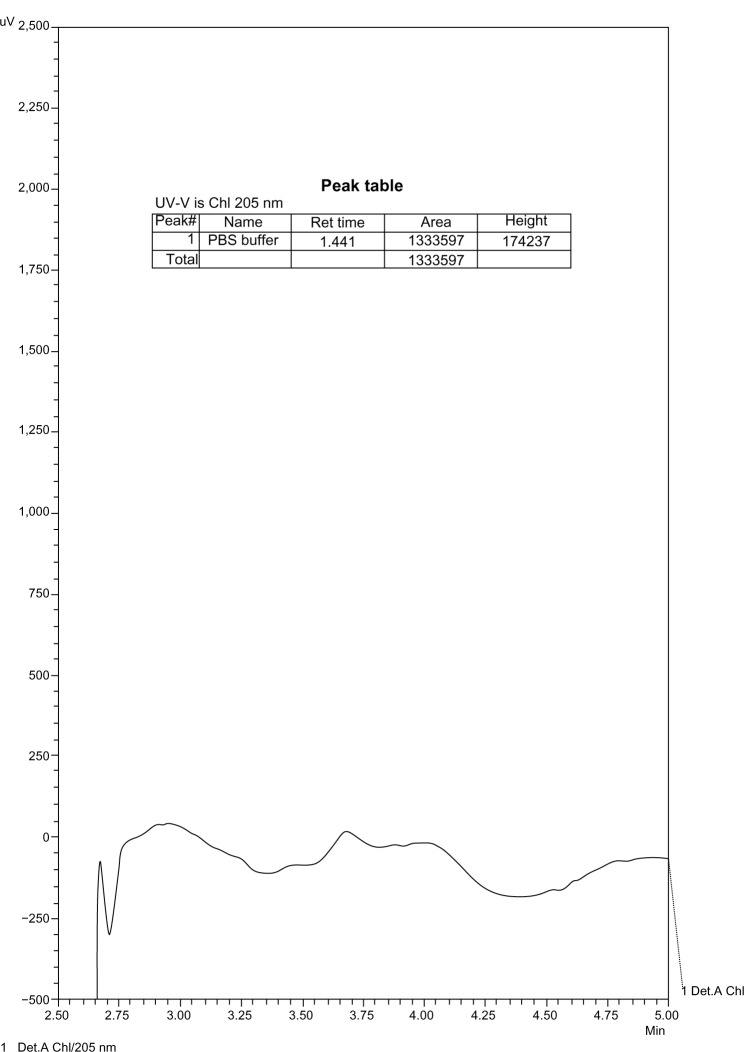

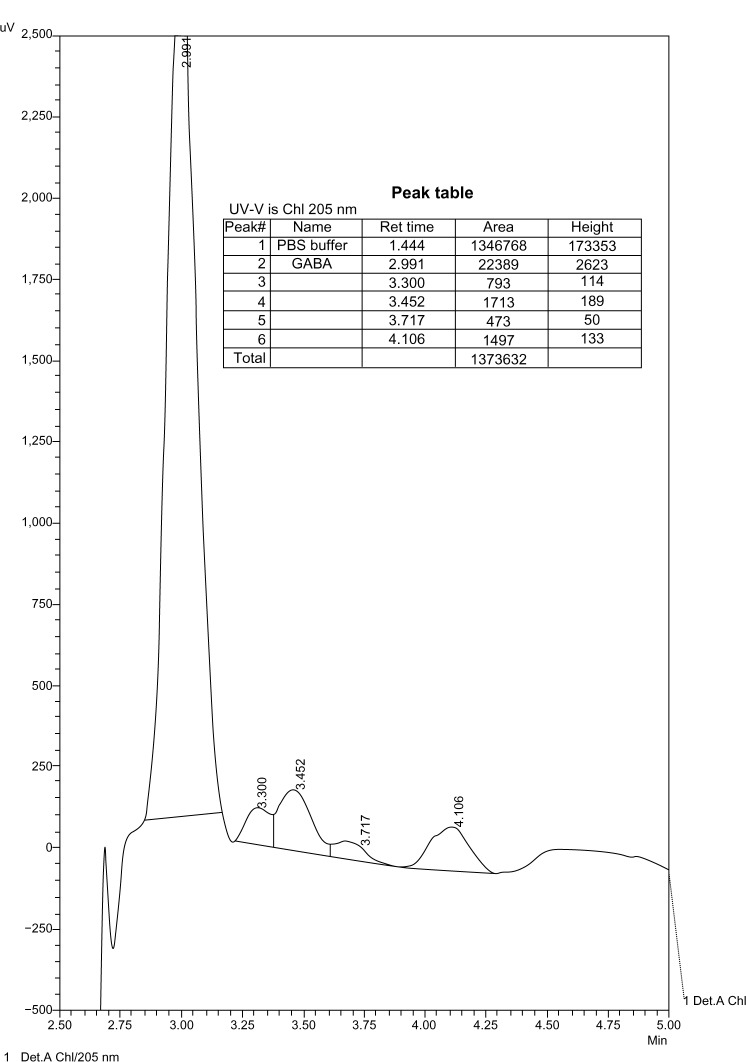

3. HPLC supports that MAO deaminates GABA at pH 7.4

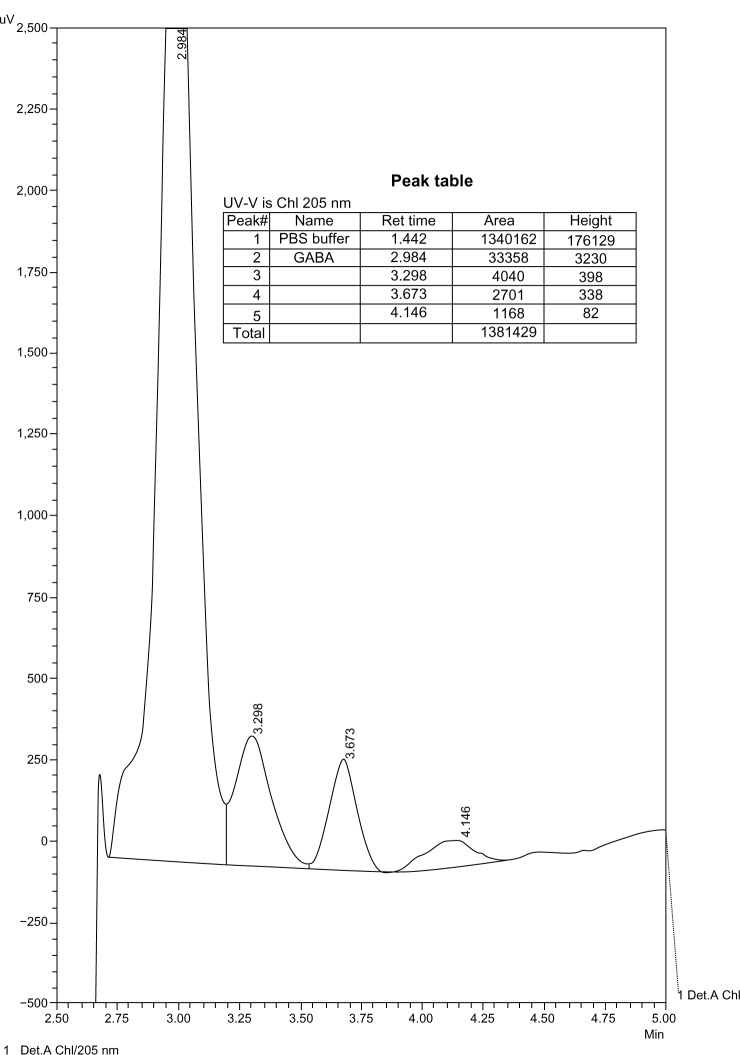

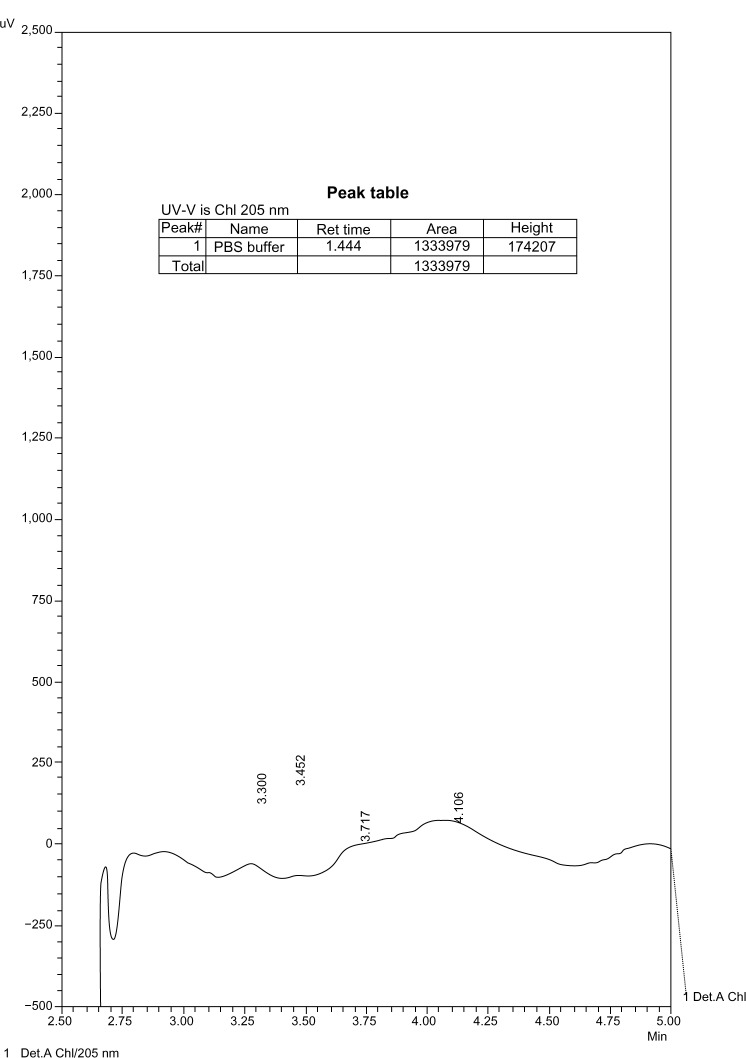

Concentrations of GABA 10−2–10−6 M were prepared in PBS. Solutions of 10 mL GABA were incubated with 50 μL of MAO-A or MAO-B (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37 °C for two hours agitated at 30-minute intervals. The solutions were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 2,000 rpm, and 1 mL of the top layer of each tube was stored at −10 °C until ready for assay. The HPLC conditions were as follows: flow rate – 0.400 mL/minute, eluent – 80:20:0.1% (H2O:CH3CN:TFA), run time –5 minutes, detector – UV (205 nm), and temperature – 30 °C.

The chromatograms show products of the reaction of GABA with MAO. These products were not detectable at lower concentrations of GABA with the same enzyme concentration, and therefore there was no interference with the enzyme (Figs. 5–9).

Figure 5.

10−2 M GABA in PBS.

Figure 9.

10−4 M GABA in PBS with MAO-B.

Results

The preliminary data support the hypothesis that in vitro at higher than physiologic concentrations, MAO deaminates GABA. If these findings are confirmed and found to occur in vivo, they could have clinical significance. Experienced psychiatrists have long known that MAOI are preferred agents for refractory depression, and these data present a possible mechanism.

Potential flaws in the concepts were as follows:

The data are preliminary without statistics. However preliminary, three distinct analytic methods support the hypothesis.

Depression is a disease with many causes. It is unlikely that correcting a deficiency of brain monoamines or GABA will be a panacea. Supporting this statement is the clinical observation that psychotherapy combined with pharmacologic therapy produces the best treatment outcome for depression.16

Discussion

If further experimental work confirms that brain MAO deaminates GABA that is deficient in depression, the under use of MAOI for the treatment of depression may need to be reexamined. Also the use of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors as first-line agents may need to be reevaluated. The reluctance to use MAOI except in patients with refractory depression may be a cause of therapeutic failures. Reviewing the literature on MAOI therapy, the risks of hypertensive crisis from food containing tyramine or postural hypotension from false neurotransmitters are quite small, but can be catastrophic.17,18 The former can be avoided through proper diet and the latter through hydration, compressive stockings, and if needed mineralocorticoid supplementation. Better physician and patient education could decrease the rare complications of serotonin toxicity from use of MAOI with some opioids or serotonin reuptake inhibitors.19,20 In patients suffering, very refractory depression treatment with MAOI combined with a stimulant such as methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine has been successful and may defer the use of electroshock therapy.17,21

Conclusion

Depression is a ubiquitous illness found in all races, cultures, and socioeconomic groups. The global burden of disease caused by depression is huge and increasing. Probably, GABA and the monoamines are involved in the cause of depression. The pH of CSF closely approximates the isoelectric point of GABA (pH = pI), and there is very good evidence to support that small quantities of very lipophilic GABA microspecies exist in the CSF. Preliminary data suggest that deamination of non-physiologic concentrations of GABA is catalyzed by MAO. Even though the quantities of lipophilic GABA and deamination products may be extremely small, in the milieu of the central nervous system, very small changes in GABA could have clinical significance. If the concepts presented in this paper can be proven, even with the known autonomic risks, treatment with MAOI may be considered earlier in the pharmacologic treatment of depression.

Figure 6.

10−2 M GABA in PBS with MAO-A.

Figure 7.

10−2 M GABA in PBS with MAO-B.

Figure 8.

10−4 M GABA in PBS with MAO-A.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to especially thank Kathy Gage and Julie Rosato of Duke University for editorial assistance.

The authors would also like to thank Thomas Van de Ven, MD, PhD, and John Toffaletti, PhD, for spectroscopy advice and David Lindsay, MD, and Jean Tetterton, NP, for taking time to review the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: JSG. Analyzed the data: JSG, CEB, DAP. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: JSG. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript JSG, CEB, DAP. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: JSG, CEB, DAP. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: JSG. Made critical revisions and approved final version: JSG, CEB, DAP. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Yitzhak Tor, Editor in Chief

FUNDING: Author(s) disclose no funding sources.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

DISCLOSURES AND ETHICS

As a requirement of publication the authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freis ED. Mental depression in hypertensive patients treated for long periods with large doses of reserpine. N Engl J Med. 1954;251(25):1006–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195412162512504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kugaya A, Sanacora G. Beyond monoamines: glutamatergic function in mood disorders. CNS Spectr. 2005;10(10):808–19. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900010403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanacora G, Gueorguieva R, Epperson CN, et al. Subtype-specific alterations of gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate in patients with major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(7):705–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rattan AK, Dhatt RK, Mangat HK. Qualitative and quantitative changes in monoamine oxidase activity after acute third ventricle treatment of GABA, muscimol, and picrotoxin in rat. Gegenbaurs Morphol Jahrb. 1989;135(2):357–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price RB, Shungu DC, Mao X, et al. Amino acid neurotransmitters assessed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy: relationship to treatment resistance in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasler G, van der Veen JW, Tumonis T, et al. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):193–200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Todd KG, Baker GB. GABA-elevating effects of the antidepressant/antipanic drug phenelzine in brain: effects of pretreatment with tranylcypromine, (-)-deprenyl and clorgyline. J Affect Disord. 1995;35(3):125–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todd KG, Baker GB. Neurochemical effects of the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine on brain GABA and alanine: a comparison with vigabatrin. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2008;11(2):14s–21s. doi: 10.18433/j34s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu PH. Deamination of aliphatic amines of different chain lengths by rat liver monoamine oxidase A and B. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1989;41(3):205–8. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1989.tb06433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenne M, Youdim MB, Ulitzur S, Finberg JP. Deamination of aliphatic amines by monoamine oxidase A and B studied using a bioluminescence technique. J Neurochem. 1985;44(5):1373–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb08772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenstein JP, Winitz M. Chemistry of the Amino Acids. Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg JS. Selected gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) esters may provide analgesia for some central pain conditions. Perspect Medicin Chem. 2010;4:23–31. doi: 10.4137/pmc.s5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazak K, Kokosi J, Noszal B. Lipophilicity of zwitterions and related species: a new insight. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2011;44:1–2. 68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frieling H, Bleich S. Tranylcypromine: new perspectives on an old drug. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(5):268–73. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0660-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saravana Babu C, Kesavanarayanan KS, Kalaivani P, Ranju V, Ramanathan M. A simple densitometric method for the quantification of inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in rat brain tissue. Chromatogr Res Int. 2011;2011:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, Andersson G. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(3):279–88. doi: 10.1002/da.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinberg SS. Combining stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review of uses and one possible additional indication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(11):1520–4. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flockhart DA. Dietary restrictions and drug interactions with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: an update. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(suppl 1):17–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11096su1c.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillman PK. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95(4):434–41. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keltner N, Harris CP. Serotonin syndrome: a case of fatal SSRI/MAOI interaction. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1994;30(4):26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.1994.tb00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawcett J, Kravitz HM, Zajecka JM, Schaff MR. CNS stimulant potentiation of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in treatment-refractory depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1991;11(2):127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]