Photosynthetic water oxidation is a fundamental chemical reaction that sustains the biosphere and takes place at a catalytic Mn4Ca site within photosystem II (PS II), which is embedded in the thylakoid membranes of green plants, cyanobacteria, and algae.1–3 The recent X-ray crystal structures with resolution between 3.2 and 3.8 Å4–7 locate the electron density associated with the Mn4Ca cluster in the multiprotein PS II complex, at different levels of detail. However, these resolutions do not allow an accurate determination of the positions of Mn4–7 and Ca,6 of distances of Mn–Mn/Ca, or the bridging and terminal ligand atoms; therefore, detailed structures critically depend on spectroscopic techniques, such as EXAFS (extended X-ray absorption fine structure)8–10 and EPR/ENDOR.11–13 In addition, our recent studies with PS II crystals show that the Mn4Ca cluster is highly susceptible to radiation damage; hence, it is impossible to obtain meaningful Mn–Mn/Ca/ligand distances from XRD under the current conditions of X-ray dose and temperature.14 EXAFS experiments require a lower X-ray dose than XRD, and radiation damage can be precisely monitored and controlled, thus allowing for data collection from an intact Mn4Ca cluster. EXAFS data also provide significantly higher Mn distance accuracy and resolution than the current 3.2–3.5 Å crystal structures.15–17 Here, we present data from a high-resolution EXAFS method using a novel multicrystal monochromator (Figure 1)18 that can distinguish two distances that are apart by ΔR ≥ 0.09 Å with an accuracy of ~0.02 Å. These data resolve a distance heterogeneity in the short Mn–Mn distances of the S1 and S2 state and thereby provide firm evidence for three Mn–Mn distances between ~2.7 and ~2.8 Å. This result gives clear criteria for selecting and refining possible structures from the repertoire of proposed models based on spectroscopic and diffraction data.

Figure 1.

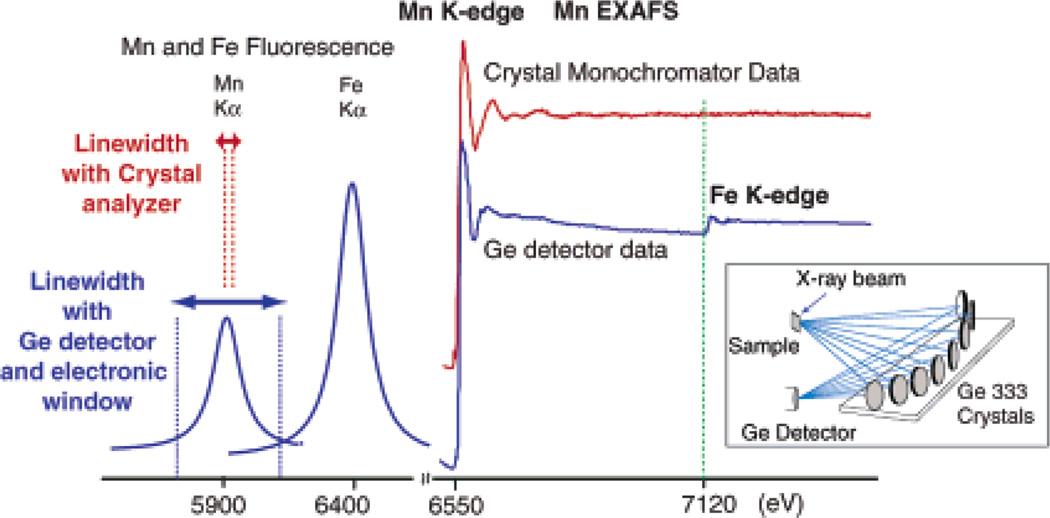

Left: A schematic representation of the detection scheme. Mn and Fe Kα1 and Kα2 fluorescence peaks are ~5 eV wide and split by ~11 eV (not shown). The multicrystal monochromator with ~1 eV resolution is tuned to the Kα1 peak (red). The fluorescence peaks broadened by the Ge detector with 150–200 eV resolution are shown below (blue).17 Right: The PS II Mn K-edge EXAFS spectrum from the S1 state sample obtained with a traditional energy-discriminating Ge detector (blue) compared with that collected using the high-resolution crystal monochromator (red). Fe present in PS II does not pose a problem with the high-resolution detector (the Fe edge is marked by a green line). Inset: The inset shows the schematic for the crystal monochromator used in a backscattering configuration.12

The new detection technique results in significant improvement in metal-backscatterer distance resolution from EXAFS. In general, EXAFS spectra of systems which contain several different metals have a limited EXAFS range because of the presence of the rising edge of the next element, thus limiting the EXAFS distance resolution (see Supporting Information for details).19 For the Mn K-edge EXAFS studies of PS II, the absorption edge of Fe in PS II limits the EXAFS energy range (Figure 1). Traditional EXAFS spectra of PS II samples are collected as an excitation spectrum by electronically windowing the Kα fluorescence (2p to 1s, at 5899 eV) from the Mn atom.15–17 The solid-state detectors that have been used over the past decade have a resolution of about 150–200 eV (fwhm) at the Mn K-edge, making it impossible to discriminate Mn fluorescence from that of Fe Kα fluorescence (at 6404 eV). The presence of the obligatory 2–3Fe/PS II (Fe edge at 7120 eV) limits the data to a k-range of ~11.5 Å−1 (k = 0.51ΔE1/2, the Mn edge is at 6540 eV and ΔE = 580 eV) (Figures 1 and 2, left). The Mn–Mn and Mn its the data to a ligand distances that can be resolved in a typical EXAFS experiment are given by ΔR = π/2kmax, where kmax is the maximum energy of the photoelectron of Mn. The use of a high-resolution crystal monochromator allows us to selectively separate the Mn K fluorescence from that of Fe (Figure 1), resulting in the collection of data to higher photoelectron energies and leading to increased distance resolution of 0.09 Å. The new detection scheme produces distinct advantages: (1) improvement in the distance resolution, and (2) more precise determination in the numbers of metal–metal vectors.

Figure 2.

Left: The k3-weighted Mn EXAFS spectra from PS II samples in S1 and S2 states obtained with conventional EXAFS detection (blue) and with a high-resolution spectrometer (range-extended EXAFS, red). Green line at k = 11.5 Å−1 denotes the spectral limit of conventional EXAFS imposed by the presence of the Fe K-edge. Right: Comparison of FTs of the Mn EXAFS spectra in conventional EXAFS collected up to the Fe edge at 11.5 Å−1 with range-extended EXAFS recorded up to 15.5 Å−1 in the S1 (green) and S2 states (black).

Earlier EXAFS studies of the S1 and S2 states of the OEC have shown that each Mn is surrounded by a first coordination shell of O or N atoms at 1.8–2.1 Å (peak I in Figure 2), a second shell of short Mn–Mn distances at ~2.7 Å (peak II), and long Mn–Mn and Mn–Ca distances at ~3.3 Å (peak III).8 These studies firmly established that the OEC in PS II is comprised of di-µ-oxo-bridged Mn2 motifs characterized by a Mn–Mn distance of ~2.7 Å (peak II). However, there was uncertainty about whether there are two or three di-µ-oxo-bridged Mn–Mn moieties20–22 because of the inherent error of the EXAFS method in the determination of the number of Mn–Mn vectors.17 Range-extended EXAFS makes it possible to resolve and discriminate between the Mn–Mn distances contributing to peak II, facilitating a more accurate determination of the total number of interactions because there must be an integral number of each of the resolved distances.

Figure 2 shows the k3-weighted Mn EXAFS spectra and the corresponding Fourier transforms (FT) of S1 and S2 states obtained using a solid-state Ge detector compared with the range-extended EXAFS data collected well past the Fe K-edge using a high-resolution crystal monochromator. The improvement in the range of the k-space data results in higher resolution and better precision in the fits.

Table 1 summarizes one and two Mn–Mn shell fits to peak II in the S1 and S2 states. The overall fit quality is monitored by comparing Φ and ε2 parameters (for details, see Supporting Information). There is significant improvement in the fit quality that contains two Mn–Mn distances of ~2.7 and ~2.8 Å over one-shell fits with an average Mn–Mn distance of ~2.74 Å. This is illustrated by two different two-shell fits in which N1 and N2 were fixed at different ratios: (1) N1:N2 = 1:1, corresponding to a scenario of two Mn–Mn interactions; and (2) N1:N2 = 2:1, corresponding to three Mn–Mn interactions. The latter case is clearly preferable based on the quality of the fits to both the S1 and S2 state data.

Table 1.

One- and Two-Shell Fits of Fourier Peak II from Range-Extended EXAFS Data from the S1 and S2 Statesa

| R(Mn-Mn) (Å) | N | σ2*103 (Å)2 | σ×103 | ε2×105 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 State | one shell | 2.72 | 1.21 | 3.0 | 0.18 | 0.060 |

| two shells | 2.68 | 0.60 | 1.0 | 0.16 | 0.054 | |

| N1:N2 = 1:1 | 2.77 | 0.60 | 1.0 | |||

| N1:N2 = 2:1 | 2.71 | 0.87 | 1.0 | 0.11 | 0.035 | |

| 2.81 | 0.44 | 1.0 | ||||

| S2 State | one shell | 2.75 | 1.20 | 2.6 | 0.13 | 0.042 |

| two shells | 2.71 | 0.60 | 1.0 | 0.11 | 0.038 | |

| N1:N2 = 1:1 | 2.79 | 0.60 | 1.0 | |||

| N1:N2 = 2:1 | 2.73 | 0.84 | 1.0 | 0.09 | 0.031 | |

| 2.82 | 0.42 | 1.0 |

N1 and N2 are the numbers of interactions for two shells with fixed σ2 (Debye–Waller parameter); Φ and ε2 are fit-quality parameters; for details see Supporting Information.

The current observation by range-extended EXAFS supports models that contain three Mn–Mn vectors: two at ~2.7 Å and one at ~2.8 Å. Models for the Mn cluster compatible with these parameters and containing one or two Mn–Mn interactions at 3.3 Å are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Models for the Mn4Ca cluster (Ca not shown) compatible with the high-resolution Mn EXAFS data with three short 2.7–2.8 Å Mn–Mn distances and one or two longer Mn–Mn distances at ~3.3 Å.

Preliminary studies using oriented PS II membranes show much better resolution for Fourier peak III and raise the possibility of resolving the Mn–Mn/Ca contributions in future studies using this high-resolution EXAFS methodology. In conclusion, two Mn–Mn distances of 2.73 and 2.82 Å in a 2:1 ratio can be resolved using this new method, proving the presence of three short Mn–Mn vectors in the S1 and S2 states of the Mn4Ca cluster.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Stephen Cramer for suggesting the range-extended EXAFS experiment and for providing access to the crystal analyzer. This work was supported by the NIH Grants GM-55302 (VKY), GM-65440 (SPC), NSF Grant CHE-0213592 (SPC), and by the Director, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences (VKY), and Office of Biological and Environmental Research (SPC) of the Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC03-76SF00098. J.M. was supported by the DFG (Me 1629/2-3). Synchrotron facilities were provided by APS, Argonne operated by DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract W-31-109-ENG-38. BioCAT is a NIH-supported Research Center RR-08630.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: High-resolution EXAFS methodology and description of the EXAFS simulations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Debus RJ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1102:269–352. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(92)90133-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutherford AW, Zimmermann JL, Boussac A. In: The Photosystems: Structure, Function, and Molecular Biology. Barber J, editor. Elsevier B. V.: Amsterdam; 1992. pp. 179–229. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ort DR, Yocum CF. Oxygenic Photosynthesis: The Light Reactions. Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zouni A, Witt HT, Kern J, Fromme P, Krauss N, Saenger W, Orth P. Nature. 2001;409:739–743. doi: 10.1038/35055589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamiya N, Shen JR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:98–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135651100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira KN, Iverson TM, Maghlaoui K, Barber J, Iwata S. Science. 2004;303:1831–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.1093087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biesiadka J, Loll B, Kern J, Irrgang KD, Zouni A. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004;6:4733–4736. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2927–2950. doi: 10.1021/cr950052k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penner-Hahn JE. Struct. Bonding. 1998;90:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sauer K, Yano J, Yachandra VK. Photosynth. Res. 2005;85:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s11120-005-0638-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peloquin JM, Britt RD. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1503:96–111. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasegawa K, Ono TA, Inoue Y, Kusunoki M. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;300:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulik LV, Epel B, Lubitz W, Messinger J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2392–2393. doi: 10.1021/ja043012j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yano J, Kern J, Irrgang KD, Latimer MJ, Bergmann U, Glatzel P, Pushkar Y, Biesiadka J, Loll B, Sauer K, Messinger J, Zouni A, Yachandra VK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:12047–12052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505207102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott RA. In: Structural and Resonance Techniques in Biological Research. Rousseau DL, editor. Orlando: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 295–362. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cramer SP. In: X-ray Absorption: Principles, Applications and Techniques of EXAFS, SEXAFS, and XANES. Koningsberger DC, Prins R, editors. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1988. pp. 257–320. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yachandra VK. Methods Enzymol. 1995;246:638–675. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)46028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergmann U, Cramer SP. SPIE Conference on Crystal and Multilayer Optics. Vol. 3448. San Diego, CA: SPIE; 1998. pp. 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glatzel P, de Groot FMF, Manoilova O, Grandjean D, Weckhuysen BM, Bergmann U, Barrea R. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter. 2005;72 Art. No. 014117. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robblee JH, Messinger J, Cinco RM, McFarlane KL, Fernandez C, Pizarro SA, Sauer K, Yachandra VK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7459–7471. doi: 10.1021/ja011621a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dau H, Iuzzolino L, Dittmer J. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1503:24–39. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusunoki M, Takano T, Ono T, Noguchi T, Yamaguchi Y, Oyanagi H, Inoue Y. In: Photosynthesis: From Light to Biosphere. Mathis P, editor. Vol. II. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 251–254. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.