Abstract

Neisseria meningitidis, the causative agent of bacterial meningitis, acquires the essential element iron from the host glycoprotein transferrin (Tf) during infection via a surface Tf receptor system composed of proteins TbpA and TbpB. Here in we present the crystal structures of TbpB from N. meningitidis, in its apo form and in complex with human Tf (hTf). The structure reveals how TbpB sequesters hTf and initiates iron release from hTf.

Neisseria sp., N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, are globally important causes of bacterial meningitis and gonorrhea, respectively. In order to colonize and infect its host, Neisseriaceae, Pasteurellaceae and Moraxellaceae pathogens have an iron uptake system based on two surface proteins, the Tf-binding proteins (Tbp) A and B, that together function to extract iron from the host iron binding glycoprotein, Tf1. TbpA is a 100kDa TonB-dependent outer-membrane protein essential for iron uptake, proposed to serve as a channel for iron transport across the outer membrane2. TbpB is a bilobed lipid-anchored protein of 60–80kDa essential for host colonization3 that extends from the outer membrane into the host milieu in order to bind and sequester Tf as the first step of iron acquisition4. Both Tbp A and B bind to Tf C-lobe5. TbpB specifically recognizes the iron loaded form of Tf, whereas TbpA binds indistinctly the holo or apo form of Tf6. Hence TbpB is proposed to recruit iron more efficiently from iron-saturated Tf in vivo. TbpB has been explored for vaccine development due to its essential function and because it can induce a protective immune response against a variety of different pathogenic bacteria7,8.

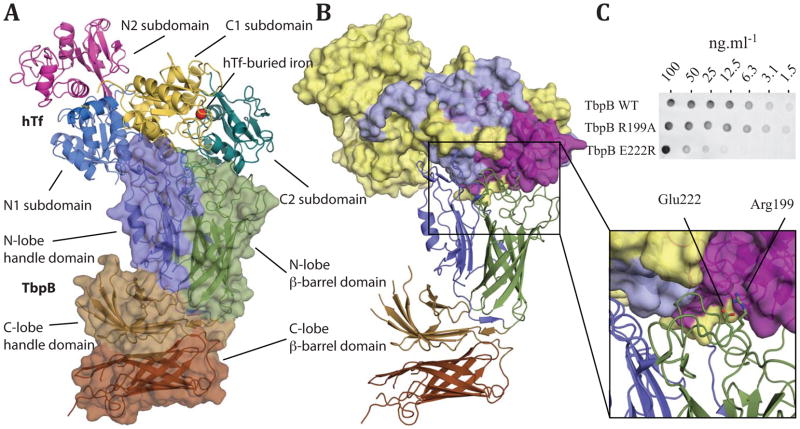

To determine the molecular events during iron uptake by TbpB, we have determined the X-ray crystal structures of the TbpB receptor from N. meningitidis M982 (NmM982), in its apo form (at 2.15 Å resolution) and in complex with hTf (at 2.95 Å resolution) (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). Similar to the previously characterized TbpB from porcine pathogens (Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and suis) 4,9, NmM982-TbpB is a bilobed protein with each lobe subdivided into a β-barrel domain and an adjacent handle domain (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

The structure of NmM982-TbpB–hTf complex. A Cartoon representation of TbpB in complex with hTf from residues 3 to 679. TbpB (residues 38 to 691) is shown as space filled diagram, whereas hTf is shown in ribbon representation; domains and subdomains from both proteins are shown in different colors and labelled. B Cartoon of TbpB in ribbon representation with subdomains colored as in (a), whereas the surface of hTf is colored based on previous hydrogen-deuterium exchange mapping12: red denotes areas protected in presence of TbpB, yellow denotes unprotected regions, and gray denotes sequences for which no peptide was detected by mass spectrometry. C Interaction of NmM982-TbpB (wild type and mutants) with hTf, assessed by binding assays on nitrocellulose membrane and anti-hTf antibody (see supplemental methods for details).

Within the TbpB–hTf complex, hTf also appears as a bilobal protein with ferric iron (Fe3+) binding sites within each of the N and C-lobes10; one iron element can be visualized within the C-lobe iron-binding site, while the N-lobe site is in the apo form (Figure 1A). Each of the hTf lobes are divided in two subdomains connected by a hinge that is at the base of a deep cleft containing the iron-binding site. The iron free N-lobe aligns structurally with the open N-lobe from the apo hTf (PDB 2HAU) previously characterized11 (r.m.s. deviation = 0.65 Å). The TbpB–hTf structure describes the first human iron-coordinated C-lobe. The C-lobe contains a hexa-coordinated Fe3+ bound to four highly conserved amino acid residues in the C1 and C2 domains: Asp392, Tyr426, Tyr517 and His585 (Supplementary Figure 2A). The final two iron coordinating groups are provided by a carbonate ion, similar to diferric rabbit and porcine Tfs (PDB 1JNF and 1H76) 10. The carbonate is stabilized by hydrogen bonds with Thr452, Arg456 and the peptide backbone amide of Ala458. Superposition of the monoferric hTf C-lobe with the diferric rabbit and porcine Tfs10 illustrates structural conservation of these C-lobe structures (r.m.s. deviation = 0.55 Å and 0.51 Å, respectively) within the closed (holo) conformation.

The TbpB–hTf complex is held together by extensive interactions between the TbpB N-lobe and the holo-hTf C-lobe. The heterodimer complex buries a substantial surface area of ~1450 Å2, in which the C1 and C2 hTf subdomains dock onto the TbpB N-lobe’s handle and β-barrel domains respectively (Figure 1). The TbpB–hTf structure is in good agreement with our predicted model created from H/D exchange mass spectrometry experiments and targeted TbpB–Tf mutant characterizations (Figure 1B) 4,9,12,13. In addition, we have validated the interface of the complex structure through binding assays with wild type and mutants (R199A and E222R) of NmM982-TbpB; insertion of a reverse of charge within the buried interface leads to a drastic loss of binding capacity (Figure 1C). The large binding interface between TbpB and hTf involves 16 hydrogen bonds, 4 salt bridges, 6 bridging waters, and hydrophobic interactions, along the entire TbpB N-lobe’s cap area (amino acid contacts are listed in Supplementary Table 2), that participate to stabilize the iron-loaded hTf C-lobe onto TbpB.

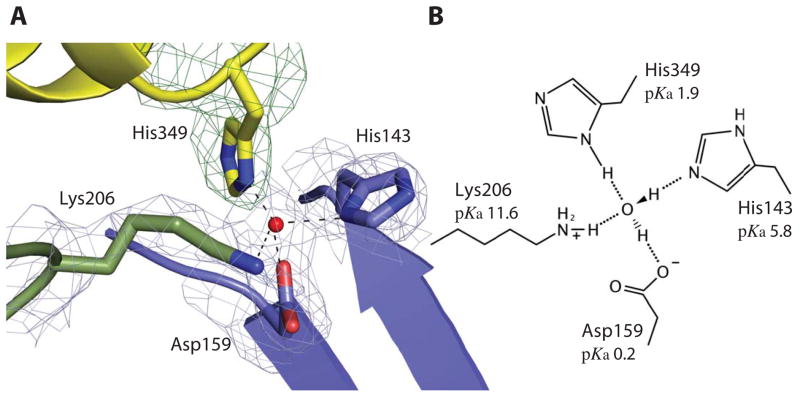

Previous works have shown that the N and C-lobes from Tf contain pH-sensitive residues monitoring the conformational changes of Tf: The di-lysine motif14 Lys206/Lys296 in N-lobe, the Lys534/Arg632/Asp634 triad15 and the His349/Lys511 motif16 within the C-lobe. Within the TbpB–hTf structure the His349/Lys511 motif in hTf is buried in the binding interface, and the His349 residue interacts with TbpB through a bridging tetra-coordinated water H-bonded to Asp159, His143, Lys206 from TbpB and His349 from hTf (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2D–H). The hTf His349 residue has been shown to play a key role as pH-inducible switch response for iron release in presence of the human Tf-receptor (TfR)16,17. Protonation of the His349 on C1 subdomain is proposed to induce electropositive repulsion with the opposite facing residue Lys511 on the C2 subdomain, leading to conformation changes and resulting in Tf opening in low pH16,17. Within the described structured water pocket, His143 (from TbpB) and the minor His349 conformation are in close proximity to the Lys511 that could elicit charge repulsion between the C1 and C2 subdomain depending of their protonated state. Structure-based pKa prediction, using PropKa18, suggests TbpB stabilizes the holo C-lobe conformation by dropping the estimated pKa of hTf His349 from 6.2 to 1.9 in the unbound and TbpB-bound forms, respectively (Figure 2B). We proposed that the hTf–TbpB interface prevents the His349 from becoming protonated, and stabilizes the iron-loaded C-lobe of hTf.

Figure 2.

TbpB stabilizes the holo form of hTf. A The cartoon representation of the buried His349 from hTf in contact with His143, Asp159, Lys206 from TbpB illustrates their interaction through a tetra-coordinated bridging water within the binding interface. The four residues and the tetrahedral coordinated water (red sphere) are embedded within a simulated annealing 2Fo-Fc electron density map at 1.0 sigma missing the hTf His349 residue. Domains colored as in figure 1a (cyan, yellow and blue denote the C1 and C2 hTf domains and the N-lobe TbpB handle domain, respectively). B The schematic model of the tetra-coordinated water is shown with structure-based predicted pKa values for each residue indicated.

Tf-bound and unbound TbpBs have almost identical main chain and loop organization in the hTf-binding site with the exception of the peripheral loop L102-124 shifting outward to allow the hTf loop L496-515 to dock on TbpB. The binding does not generate any major structural changes within TbpB (r.m.s. deviation = 0.4 Å between bound/unbound N-lobe, Supplementary Figure 1B). The TbpB–hTf recognition acts almost like a rigid body docking between the two proteins. The only feature differentiating the hTf-bound to the unbound TbpB consists of a torsion rotation of 5.4° into the orthogonal lattice between the TbpB N and C-lobe which could be attributed to crystal contacts (Supplementary Figure 3).

The bacterial TbpB receptor competes for Tf with the mammalian Tf-receptor (TfR) that is located on the surface of host cells and mediates iron release from Tf in a pH-dependant mechanism driven by the acidification of the endosome. The TfR-binding site on Tf is described on both N and C-lobes domain of Tf17, while the bacterial receptor TbpB binds uniquely to the C-lobe domain of Tf. The TbpB-binding site on hTf overlaps partially with the TfR-binding interface, sharing helix1 as a common interaction site (Supplementary Figure 4). This overlapping binding site on hTf for host and invading Neisseriaceae, Pasteurellaceae or Moraxellaceae pathogens provides the bacteria with assurance that mutations on Tf do not give the host any advantage in terms of iron sequestration from Tf, as both TfR and TbpB directly compete for a similar surface on hTf.

The mammalian TfR has no retrieving specificity while the bacterial receptor TbpB binds uniquely to its host species holo-Tf19 in defiance of the high sequence conservation among seroTfs. Distinctly from TfR, TbpB interacts with the loop L496-515 of hTf that represents a region of diversity in length and sequence between mammalian homologs of Tf (Supplementary Figure 4E); superposition of the hTf with porcine Tf (pTf) illustrates that steric hindrance between L496-515 and NmM982-TbpB would prevent NmM982-TbpB from forming a complex with pTf. These variations within the loop L496-515 of the TbpB-recognition site on hTf seem to address a major barrier for cross-species specificity between the TbpB pathogen receptors and Tfs. Furthermore, the TbpB–hTf complex structure provides the structural explanation of the TbpB specificity for the holo-form of the Tf C-lobe as both the C1 and C2 subdomains dock on TbpB whereas the open conformation is characterized by a 51° rotation of the C2 domain, which would drastically reduce the binding interface between TbpB and Tf.

The structural data presented here provides the basis for Tf–TbpB recognition, an essential function leading to the survival of many host-restricted pathogens including Neisseria meningitidis in the iron-limited environment of the host blood20. Our data reveal TbpB does not initiate the opening of the hTf holo C-lobe leading to the iron release. But instead, the X-ray crystal structure of TbpB–hTf demonstrates that TbpB buries the critical hTf residue His349 in a controlled environment that leads to stabilization of the hTf C-lobe holo form. This is consistent with the function of TbpB to recruit and sequester iron-loaded Tf while in the host, and maintain the iron-loaded status of Tf until its delivery to TbpA. This structural insight of TbpB–hTf during the first step of the iron acquisition process suggests that TbpA or the ternary complex hTf–TbpA–TbpB initiates conformational changes within Tf to release iron as the second step of the iron acquisition mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Advance Photon Source (APS) at both of NE-CAT’s beamlines 24-ID-E and 24-ID-C, the Canadian Light Source (CLS) beamline staff at CMCF-08ID-1 for assistance with data collection, and members of the Moraes and Schryvers laboratories for valuable discussion. This research was funded with operating and infrastructure support provided by Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI), Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (AIHS), and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Footnotes

Accession codes. Structure factors and atomic coordinates for NmM982-TbpB and the NmM982-TbpB–hTf complex have been deposited with accession codes 3VE2 and 3VE1, respectively.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

CC, ABS and TFM conceived and designed the experiments; CC performed experiments and data analysis; JA provided the wild type NmM982-TbpB containing plasmid; RHY provided deglycosylated hTf; CC and TFM wrote the manuscript. All authors read and commented on the draft versions of the manuscript and approved the final version.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Gray-Owen SD, Schryvers AB. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:185–91. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelissen CN, et al. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:611–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baltes N, Hennig-Pauka I, Gerlach GF. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;209:283–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moraes TF, Yu RH, Strynadka NC, Schryvers AB. Mol Cell. 2009;35:523–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcantara J, Yu RH, Schryvers AB. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1135–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Retzer MD, Yu R, Zhang Y, Gonzalez GC, Schryvers AB. Microb Pathog. 1998;25:175–80. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danve B, et al. Vaccine. 1993;11:1214–20. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers LE, et al. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4183–92. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4183-4192.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calmettes C, et al. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12683–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall DR, et al. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:70–80. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901017309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wally J, et al. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(34):24934–24944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604592200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling JM, Shima CH, Schriemer DC, Schryvers AB. Mol Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva LP, et al. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:21353–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.226449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinlein LM, Ligman CM, Kessler S, Ikeda RA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13696–703. doi: 10.1021/bi980318s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbrooks PJ, et al. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3701–7. doi: 10.1021/bi027071q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steere AN, et al. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15:1341–52. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0694-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckenroth BE, Steere AN, Chasteen ND, Everse SJ, Mason AB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13089–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105786108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Robertson AD, Jensen JH. Proteins. 2005;61:704–21. doi: 10.1002/prot.20660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schryvers AB, Gonzalez GC. Can J Microbiol. 1990;36:145–7. doi: 10.1139/m90-026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Echenique-Rivera H, et al. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002027. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.