Abstract

Animal metabolic rate is variable and may be affected by endogenous and exogenous factors, but such relationships remain poorly understood in many primitive fishes, including members of the family Acipenseridae (sturgeons). Using juvenile lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens), the objective of this study was to test four hypotheses: 1) A. fulvescens exhibits a circadian rhythm influencing metabolic rate and behaviour; 2) A. fulvescens has the capacity to regulate metabolic rate when exposed to environmental hypoxia; 3) measurements of forced maximum metabolic rate (MMRF) are repeatable in individual fish; and 4) MMRF correlates positively with spontaneous maximum metabolic rate (MMRS). Metabolic rates were measured using intermittent flow respirometry, and a standard chase protocol was employed to elicit MMRF. Trials lasting 24 h were used to measure standard metabolic rate (SMR) and MMRS. Repeatability and correlations between MMRF and MMRS were analyzed using residual body mass corrected values. Results revealed that A. fulvescens exhibit a circadian rhythm in metabolic rate, with metabolism peaking at dawn. SMR was unaffected by hypoxia (30% air saturation (O2sat)), demonstrating oxygen regulation. In contrast, MMRF was affected by hypoxia and decreased across the range from 100% O2sat to 70% O2sat. MMRF was repeatable in individual fish, and MMRF correlated positively with MMRS, but the relationships between MMRF and MMRS were only revealed in fish exposed to hypoxia or 24 h constant light (i.e. environmental stressor). Our study provides evidence that the physiology of A. fulvescens is influenced by a circadian rhythm and suggests that A. fulvescens is an oxygen regulator, like most teleost fish. Finally, metabolic repeatability and positive correlations between MMRF and MMRS support the conjecture that MMRF represents a measure of organism performance that could be a target of natural selection.

Introduction

Animal metabolic rate is variable and may be influenced by both endogenous factors (e.g. circadian rhythm, individual physiological traits) and exogenous factors (e.g. oxygen availability). A surge of research interest continues to uncover the mechanistic basis of variability in metabolic rate [1], and metabolic rate is now one of the most widely measured physiological traits in animals [2]. In many aquatic animals, measurements of oxygen consumption rate (MO2) provide a robust proxy for aerobic metabolic rates. Under static conditions, measurements of MO2 are typically repeatable in individual animals, suggesting that metabolic rate may be an organismal trait [3], although the repeatability tends to decline over time [2].

Circadian rhythms in physiology and behaviour have evolved to allow animals to anticipate changes in the light-dark environment that are tied to the rotation of Earth. Circadian rhythms reflect endogenous rhythms that are self-sustained, unlike exogenous rhythms that depend on external factors, including changing light levels [4]. Circadian rhythms play a tremendous role in most organisms; ranging from decentralized regulation of the daily timing of mitosis [5] to influencing the migration of animals [6]. Circadian rhythms have been described in details in several teleost fishes [4], [5], [7], [8]. For example, circadian rhythms influencing metabolic rate and behaviour have been documented in Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus [9] and puffer fish Takifugu obscurus [10]. In contrast, in many primitive fishes, the influence of circadian rhythms on metabolism and behaviour remains largely unknown.

Standard metabolic rate (SMR) is a basic maintenance requirement measured as the minimum rate of oxygen consumption of postprandial unstressed animals at rest [11]. Long-term energy demands for swimming, food acquisition and treatment, regulation owing to environmental perturbation, and reproduction are additional to standard metabolism [11]. These demands are met within the range set by the maximum metabolic rate (MMR) [11].

Animal metabolic physiology is often influenced by exogenous factors, including environmental hypoxia. Hypoxia occurs in a wide range of aquatic systems [12], and the severity, frequency of occurrence, and spatial scale of hypoxia have increased in the last few decades, primarily due to anthropogenic activity [13], [14]. There are two distinct metabolic responses to environmental hypoxia: 1) oxygen independent respiration in which the metabolic rate remains constant in spite of changing oxygen availability; and 2) oxygen dependent respiration in which the metabolic rate varies with oxygen availability [15]. The two responses are commonly termed oxygen regulation and oxygen conformity, respectively. The vast majority of literature suggests that most teleost fish are oxygen regulators [16]–[20], capable of maintaining both MMR and SMR down to certain oxygen thresholds [21], [22]. In contrast, it remains controversial if oxygen regulation or conformity occurs in a number of primitive fishes exposed to hypoxia. For example, among members of the family Acipenseridae (sturgeons), previous studies have reported conflicting results stating that the metabolic rate remains constant or tends to increase [23]–[26] (i.e. oxygen regulator) or decrease [27]–[30] (i.e. oxygen conformer) when Acipenserids are exposed to environmental hypoxia. Using Adriatic sturgeon Acipenser naccarii, McKenzie et al. [31] suggested that swimming A. naccarii are oxygen regulators, whereas immobile A. naccarii are oxygen conformers. Knowing whether species are oxygen regulators or conformers is important to understand the capacity of fish to respond to environmental changes [20] and to assess assumptions for disparate metabolic theories in ecology [19].

Intraspecific variation in animal metabolic rate may correlate with endogenous factors, including behavioural or life history traits [32], [33]. For example, Niitepõld and Hanski [34] found positive correlations between MMR and life span in a species of butterfly. In fish, MMR is typically measured in the laboratory using either a critical swimming protocol [35] or a chase protocol [36]. Using the latter protocol, Norin and Malte [3] reported that MMR is repeatable over several weeks. Assuming repeatability and heritability, MMR may represent a measure of organism performance [3], and it is possible that the trait is subjected to natural selection and could evolve over time. Little is known, however, about potential correlations between forced MMR (MMRF; e.g. measured using the chase protocol) and spontaneous MMR (MMRS) measured in volitionally performing fish. For example, is there a positive relationship between MMRF and MMRS such that an individual fish with an unexpectedly high MMRF also has an unexpectedly high MMRS? Clarifying potential correlations between MMRF and MMRS is important, because from an evolutionary point of view, selection regimes may not always operate on a trait's maximal value, but rather on the spontaneous use of the trait [37], [38]. If MMRF and MMRS are correlated, measurements of MMRF could function as a predictor of MMRS in individual fish.

Using juvenile lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens), we employed intermittent flow respirometry and video analysis to test four hypotheses: 1) A. fulvescens exhibit a circadian rhythm influencing metabolic rate and behavior; 2) A. fulvescens has the capacity to regulate metabolic rate when exposed to environmental hypoxia; 3) measurements of MMRF are repeatable in individual fish, and 4) MMRF is positively correlated with MMRS.

Our results reveal that the metabolic rate of A. fulvescens is influenced by a circadian rhythm, and A. fulvescens has the capacity to regulate SMR when exposed to environmental hypoxia, demonstrating oxygen regulation. In contrast, MMRF tends to decrease with increasing levels of hypoxia. Measurements of residual body mass corrected MMRF are repeatable in individual A. fulvescens; and residual body mass corrected MMRF and MMRS are correlated positively, but only in A. fulvescens exposed to an environmental stressor including hypoxia or 24 h of light.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Manitoba, Canada (Approval ID: AUP-F11-004) under the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care. No animals were sacrificed, all efforts were taken to ameliorate animal suffering and undue stress, and there was no mortality during any of the tests.

Experimental animals

A total of 70 juvenile A. fulvescens (body mass: 30.51±1.21 g (mean ± S.E.); age: 1+; sex: unknown) obtained from Grand Rapids Fish Hatchery (Grand Rapids, MB, Canada) were kept at 17±1°C in flow-through holding tanks at the University of Manitoba, Canada. The light regime was 12 h light: 12 h dark (12L∶12D). A. fulvescens were fed daily using a mixture of bloodworm (San Francisco Bay Brand, Newark, CA, USA) and sinking trout pellet (Martin Mills Ltd., Elmira, ON, Canada).

Respirometry

Four static respirometers (each 0.83 l) and a mixing pump were submerged in a 100 l opaque tank, filled with freshwater maintained at 17±0.1°C. Oxygen content (% air saturation; O2sat) of the water in the tank was controlled using two air stones combined with a stream of nitrogen bubbles [39]. Depending on the experiment, water in the tank was maintained at an oxygenation level between 100% and 30% O2sat.

Respirometers were made of transparent glass tubing and were designed to allow a degree of spontaneous activity of A. fulvescens, including body undulations with tail excursions>90° relative to the body axis. Respirometers were situated in a sound isolated room with no other ongoing experiments to minimize any disturbance of the fish.

Measurements of MO2 (mg O2 h−1) were carried out every 9 min using computerized intermittent flow respirometry allowing long term (>48 h) repeated measurements [40]. Each respirometer was fitted with two outlet and two inlet ports as described previously [41]. The repeated respirometric loops consisted of a 4 min flushing phase during which a pump flushed the respirometer with ambient water through one set of ports. The second set of ports and a pump secured re-circulation of water in the respirometer in a closed circuit phase for 5 min, divided into a waiting phase (2 min) and a measurement phase (3 min).

Oxygen partial pressure was measured at 1 Hz by a fiber optic sensor (Fibox 3 connected to a dipping probe; PreSens, Regensburg, Germany) located in the re-circulated loop. The flush pump was controlled by AutoResp software (version 2.1.3; Loligo Systems, Tjele, Denmark) that also calculated the MO2 in the measurement phase using the oxygen partial pressure and standard equations [42], [43]. Preliminary testing demonstrated that the duration of the measurement phase (3 min) ensured that the coefficient of determination (r2) associated with each MO2 measurement was always>0.95, similar to previous studies [44]. Corrections of background respiration (i.e. microbial respiration) followed Jones et al. [45].

Experimental protocols

A. fulvescens were selected randomly and fasted for 48 h to ensure a post absorptive state prior to experimentation. Subsequently, A. fulvescens were introduced to the respirometers and acclimated for 20 h. The light regime during the fasting and acclimation periods was 12L∶12D, which included 0.5 h of gradually shifting light intensity from light to darkness and vice versa. Light intensities were 3.0 and 0.0 μmol s−1 m−2 in daylight and darkness, respectively. Starting at 16:00 h on the next day, MO2 data were collected for the following 24 h.

Measurements of MO2 over 24 h comprised three test groups: 1) control (100% O2sat; 12L∶12D); 2) treatment A (30% O2sat; 12L∶12D); and 3) treatment B (100% O2sat; 24L). The oxygen content in treatment A (30% O2sat) corresponded to approximately 6.2 kPa. Data collection for the three test groups was carried out in a random fashion and each test group included 10–12 individuals. After each 24 h trial, MMRF was measured as described below.

Standard metabolic rate (SMR) and maximum metabolic rates (MMRF and MMRS)

For each test group, SMR in individual fish was estimated as the average of the lowest 10 MO2 values collected over 24 h. This method to estimate SMR was employed because it provides measurements that are repeatable in individual fish [3].

MMRF was measured immediately after each 24 h trial at the corresponding O2sat level (i.e. 100% or 30% O2sat) inside the respirometer. MMRF was elicited using a standard chase protocol [36]. Briefly, individual A. fulvescens were transferred to a circular trough and chased to exhaustion, similar to previous studies on Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrhynchus) and shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum) [46]. Upon exhaustion, identified by no further response after 5 min of manual stimulation, A. fulvescens were transferred (<20 s) to the respirometer where MO2 measurements started immediately. MMRF was the highest of three consecutive MO2 measurements.

In addition, following the same chase protocol, MMRF was measured in 36 A. fulvescens exposed to 100%, 90%, 80% or 70% O2sat inside the respirometer. A total of 8–12 A. fulvescens were tested at each of the four O2sat levels. Measurements of MMRF in 100% O2sat were repeated after 4.5 h to examine the short term repeatability of MMRF in individual fish. These two measurements were termed initial and final MMRF.

Finally, for each test group (i.e. control and treatments A and B), MMRS was estimated as the single highest measurement of MO2 (i.e. one respirometric loop) in volitionally performing individual fish during the complete 24 h trial (i.e. after acclimation). These data were used to test for correlations between MMRF and MMRS in individual fish (see Data analysis).

Behaviour

A. fulvescens in the respirometers were recorded (25 frames s−1) dorsally using a UEye camera (model UI-1640SE-C-GL; IDS, Woburn, MA, USA) equipped with a CCTV lens (model HF6M-2; Spacecom, Whittier, CA, USA). The software UEye Cockpit (version 3.90; IDS, Woburn, MA, USA) was used to download recordings to a PC. Two Scene illuminators (model S8030-30-C-IR; Guangdong, China) provided infra-red light for nocturnal recordings. All recordings were synchronized with the respirometric loops (to the nearest 1 s). For each A. fulvescens, behavioural data were collected over a 45 s time interval during the measurement phase of the respirometric loop (i.e. once every 9 min.). Behavioural data included total activity (i.e. % of time moving), and the number of body undulations with tail excursions<90° or >90° relative to the body axis (i.e. body undulations min−1). For each test group, behavioural data were collected over a 1 h time interval (i.e. 6–7 respirometric loops) at 16, 20, 21, 22 and 23 h. These hourly measurements were selected to record simultaneous metabolic and behavioural changes during the light-dark transition at 21 h.

Data analysis

MO2 data were body mass adjusted following previous studies [47]. Metabolic rates from the three test groups were calculated over 1 h intervals [48], with two exceptions, because the light intensity was gradually changing over 0.5 h periods at 21 h and 9 h. Therefore, the two 1 h intervals associated with 21 h and 9 h were each divided into two: 0.5 h with changing light intensities and 0.5 h with constant light intensity. The compiled data were used to compare metabolic rates over 24 h within the three test groups (i.e. control and treatments A and B). Behavioural data were compiled in the same fashion.

Metabolic and behavioural variables were compared within each test group across the time interval from 16:00 to 23:00 h using a repeated measure (RM) one way ANOVA. Relationships between behaviour and metabolic rates were investigated using least squares linear regression.

To test for metabolic differences, SMR, MMRF and MMRS measurements were compared between the three test groups using a one way ANOVA. MMRF data from the four oxygen treatments (100 – 70% O2sat) were analyzed using least square linear regression to examine the effect of decreasing oxygen levels on MMRF.

The method recommended by Norin and Malte [3] was used to examine repeatability of the MMRF measurements. All values of MMRF and body mass were log10-transformed prior to the analysis. Mass-independent data of MMRF were expressed as residual values using the relationship between body mass and MMRF. Fish with higher than expected MMRF have positive residuals and fish with lower than expected MMRF have negative residuals. Repeatability of the two sets of residuals (initial and final) was estimated using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) [3].

Using metabolic rate data from the three test groups, MMRS of each individual fish was extracted to test for correlations between individual MMRF and MMRS. The comparison of individual MMRF and MMRS was carried out in the same fashion as the repeatability analysis described above.

Log10 transformations of data prior to statistical analysis were employed to meet assumptions of normal distribution of data and homogeneity of variance. If the assumptions were met, ANOVA or RM ANOVA were employed depending on design as described above. If significant, the tests were followed by pairwise multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method.

If data transformations did not permit the use of parametric testing, ANOVA on ranks or RM ANOVA on ranks (Friedman) were employed depending on design as described above. The tests were followed by pairwise multiple comparisons using Dunn's method to take unequal sample sizes into account.

Tests were carried out using SigmaStat 3.01 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA) and SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Results were considered significant if α<0.05. All values are reported as means ± S.E. unless noted otherwise.

Results

For all the experiments, there were no indications that the health status of the test animals changed during any of the tests.

Body mass adjustments

There were no differences between test groups (i.e. control, treatments A and B) in terms of body mass and SMR measured as mg O2 h−1 (both P>0.05). Consequently, SMR data were pooled, and the relationship between log10 SMR and log10 body mass was described using a linear equation [3], [47]. The slope of the relationship was 1.00±0.12 indicating that a 1.0 body mass scaling coefficient was appropriate for the SMR data. A 1.0 body mass scaling coefficient is consistent with two previous studies on green sturgeon Acipenser medirostris [47], [49]. Because the 1.0 body mass scaling coefficient was appropriate for the SMR data, the same coefficient was used for the MO2 data collected over time (Fig. 1).

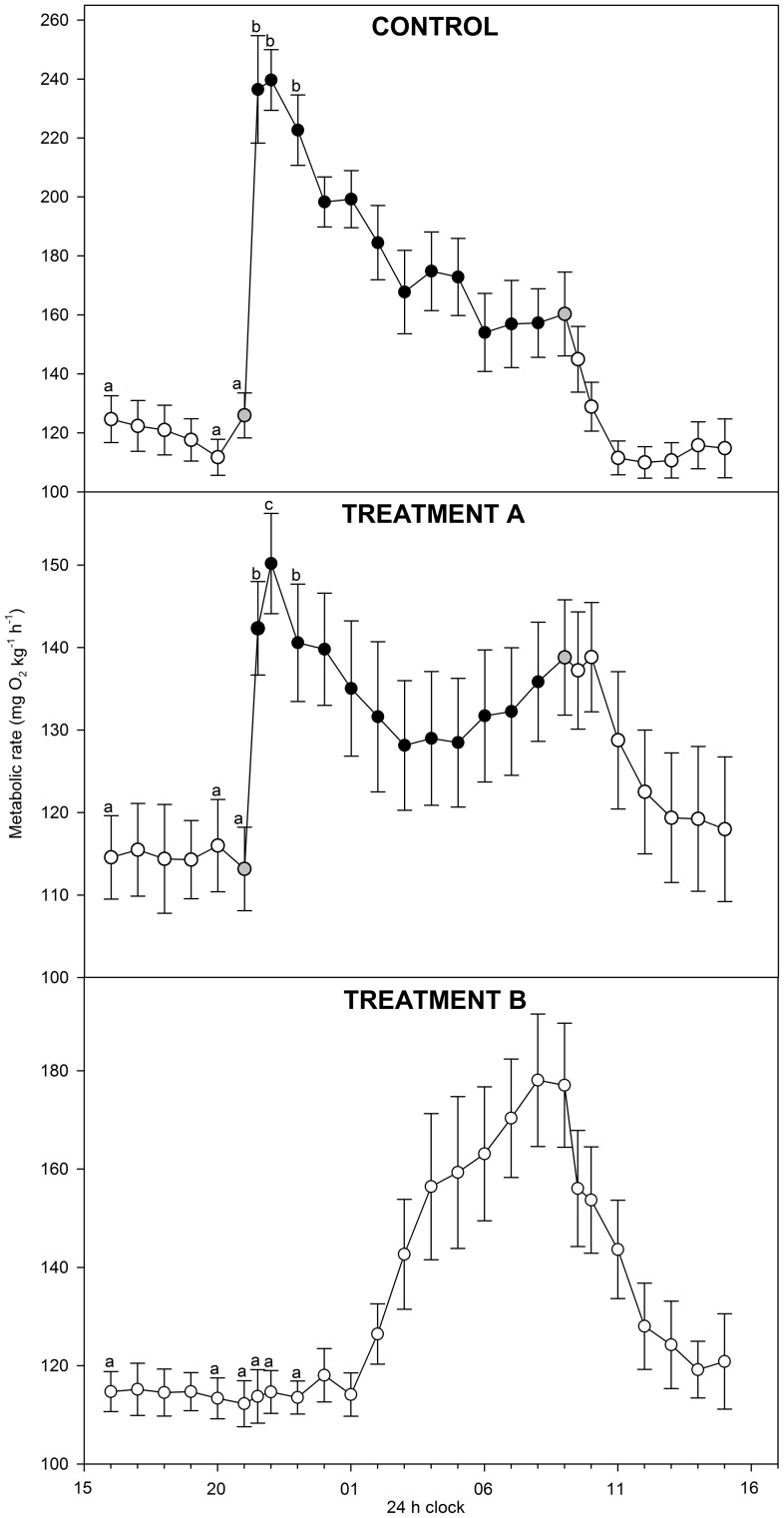

Figure 1. Metabolic rates (mg O2 kg−1 h−1) over 24 h in lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens.

Data collection comprised three test groups: control (100% O2sat; 12L∶12D), treatment A (30% O2sat; 12L∶12D), and treatment B (100% O2sat; 24L). Colours of the symbols indicate light levels with white, black and grey data points representing light, dark and intermediate light levels, respectively. Different letters indicate significant (P<0.05) differences between measurements within each test group. Note that y-axes differ between the three panels.

MMRF measured as mg O2 h−1 did not differ between the control group and treatment B (P>0.05), but MMRF from treatment A was lower than both the control group and treatment B (P<0.001). To examine the relationship between body mass and MMRF (mg O2 h−1), data collected in normoxia were combined and the relationship between log10 MMRF and log10 body mass was described using a linear equation [3], [47]. The slope of the relationship was 0.90±0.05 indicating that a 0.9 body mass scaling coefficient was appropriate for the MMRF data. Consequently, all MMRF data were standardized to the mean body mass of 30.5 g using 0.9 as the body mass scaling coefficient. In the following, MMRF standardized to 30.5 g is denoted MMRF30.5.

Metabolic rates over 24 h

Metabolic rates varied substantially over the 24 h periods (Fig. 1). In the control group, metabolic rate increased significantly (P<0.001) from 112 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 at 20:00 h to reach a maximum of 237 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 when the light went off (Fig. 1, control), indicating a dusk metabolic peak. Thereafter, metabolic rate decreased and reached 157 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 shortly before daylight. The metabolic rate decreased further in daylight and reached 112 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 after 3 h.

In treatment A, metabolic rate increased significantly (P<0.05) from 116 to 150 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 when the light went off (Fig. 1, treatment A). Although truncated, this metabolic peak corresponded to the dusk metabolic peak observed in the control test group. Thereafter, metabolic rate decreased to 128 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 at 03:00 h, and then increased to reach 139 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 during the period with increasing light intensity (09:00 h). Thus, treatment A indicated two metabolic peaks; one associated with dusk and one associated with dawn. After the light went on, the metabolic rate changed little for 1 h and then decreased to 118 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 (Fig. 1, treatment A).

In treatment B, the metabolic rate remained below 119 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 until 02:00 h (Fig. 1, treatment B). Data showed that the dusk metabolic peak, observed in the control group and in treatment A, was eliminated by the constant light (P = 0.64). In contrast, in treatment B, the metabolic rate tended to increase at 02:00 h and continued doing so until it reached 178 mg O2 kg−1 h−1 at 08:00 h (Fig. 1, treatment B). These data indicated the presence of a darkness independent increase in the metabolic rate. The increasing metabolic rate peaked around dawn, just before the light would normally come on.

Collectively, data indicated the presence of two metabolic peaks occurring over 24 h. The first metabolic peak occurred around dusk and was noticeable in the control group and treatment A (Fig. 1). The second metabolic peak occurred around dawn and was noticeable in treatments A and B (Fig. 1).

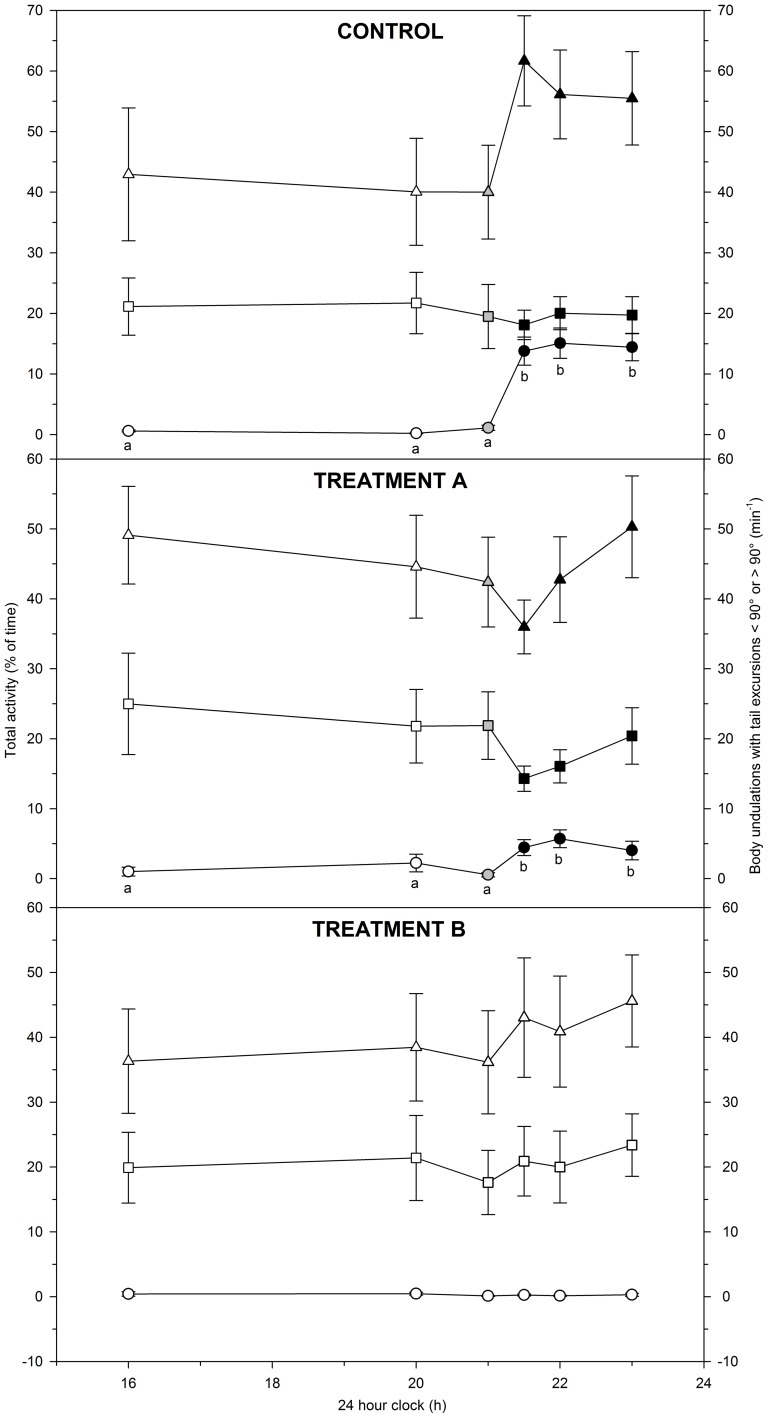

Behaviour across the light-dark transition

Behavioural recordings from the control group indicated that the total activity increased in darkness (Fig. 2, control), but no statistically significant differences were identified over time (P>0.05). Similarly, the frequency of body undulations with tail excursions<90° did not change significantly over time (P>0.05). In contrast, body undulations with tail excursions>90° increased significantly over time (P<0.001) (Fig. 2, control).

Figure 2. Hourly behavioural variables in lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens from 16:00 h to 23:00 h.

Data collection comprised three test groups: control (100% O2sat; 12L∶12D), treatment A (30% O2sat; 12L∶12D), and treatment B (100% O2sat; 24L). Colours of the symbols indicate light levels with white, black and grey data points representing light, dark and intermediate light levels, respectively. Behavioural variables included total activity (% of time moving) (triangles) and the frequencies of body undulations with tail excursions<90° (squares) or >90° (circles) (min−1). Within each test group, behavioural variables were compared over time to identify significant changes. Different letters indicate significant (P<0.05) changes over time, whereas identical or no letters indicate non-significant (P>0.05) changes over time.

Data from treatment A revealed no significant changes in the total activity over time or in the frequency of body undulations with tail excursions<90° (both P>0.05) (Fig. 2, treatment A). In contrast, the frequency of body undulations with tail excursions>90° increased significantly over time (P<0.001).

Data from treatment B revealed no significant changes over time in the total activity or in the frequencies of body undulations with tail excursions<90° or >90° (all P>0.05; Fig. 2, treatment B).

Correlations between behaviour and metabolic rate

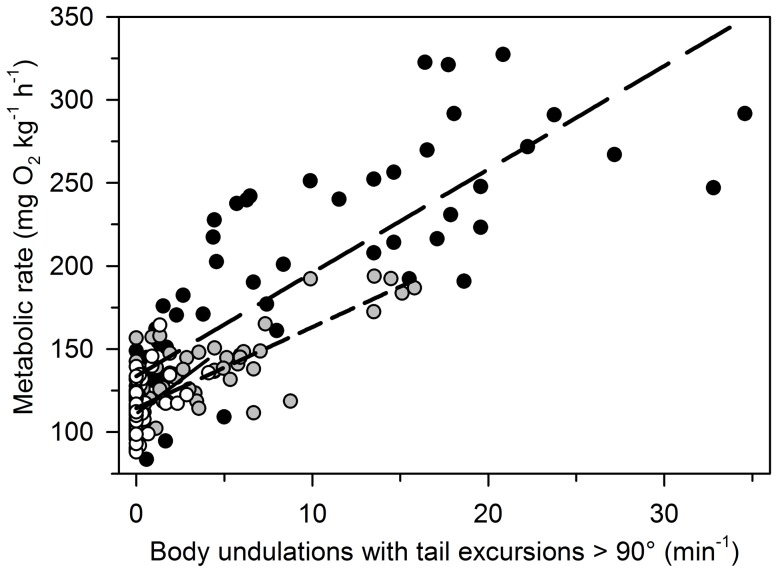

The behavioural data suggested that the frequency of body undulations with tail excursions>90° (Fig. 2) could be a major driver of the increase in metabolic rate associated with dusk (Fig. 1). Regression analysis revealed highly significant (P<0.001 in all cases) linear relationships between the frequency of body undulations with tail excursions>90° and metabolic rate (Fig. 3). The coefficients of determination (r2) for the relationships varied between test groups and were 0.68, 0.64 and 0.15 for control and treatments A and B, respectively (Fig. 3). These data suggest that metabolic variation was coupled with behavioural variation.

Figure 3. Metabolic rates (mg O2 kg−1 h−1) correlate positively with behaviour in lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens.

Behaviour involved body undulations with tail excursions>90° (min−1). Data were collected from 16:00 h to 23:00 h. Data collection comprised three test groups: control (100% O2sat; 12L∶12D), treatment A (30% O2sat; 12L∶12D), and treatment B (100% O2sat; 24L). Note that symbol colours indicate the three test groups: control (black symbols; long dash line), treatment A (gray symbols; short dash line) and treatment B (white symbols; solid line). The three corresponding linear least squares regressions are highly significant (all P<0.001) and the coefficients of determination (r2) are 0.68, 0.64 and 0.15, respectively.

Environmental effects on standard metabolic rate (SMR) and forced maximum metabolic rate (MMRF)

SMR was unaffected by hypoxia (treatment A) and constant light (treatment B) (P>0.05; Table 1), and the pooled average was 92.39±2.00 mg O2 kg−1 h−1. Corresponding analyses of MMRF30.5 revealed no differences between the control and treatment B (P>0.05), whereas MMRF30.5 from treatment A was lower than both the control and treatment B (P<0.001; Table 1). These findings showed that 30% O2sat reduced MMRF30.5.

Table 1. Metabolic variables (mean ± S. E.) in lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens representing three different test groups: control (100% O2sat; 12L∶12D); treatment A (30% O2sat; 12L∶12D); and treatment B (100% O2sat; 24L).

| Metabolic variable | Control | Treatment A | Treatment B |

| SMR (mg O2 kg−1 h−1) | 88.44±3.54a | 97.23±4.06a | 91.50±2.34a |

| MMRF30.5 (mg O2 kg−1 h−1) | 338.25±8.06a | 167.49±5.81b | 328.43±8.29a |

| MMRS (mg O2 kg−1 h−1) | 311.91±13.60a | 168.72±7.57b | 265.24±18.44c |

Sample size (n) is 8–12 for each test group. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences (P<0.05) between test groups. SMR is the standard metabolic rate. MMRF30.5 and MMRS are the forced and spontaneous maximum metabolic rates, respectively. Measurements of MMRF30.9 are body mass adjusted to a 30.5 g fish. Body mass adjustments of MMRS to a 30.5 g fish (i.e. equivalent to MMRF30.5) change MMRS values by <1% and have no impact on the conclusions.

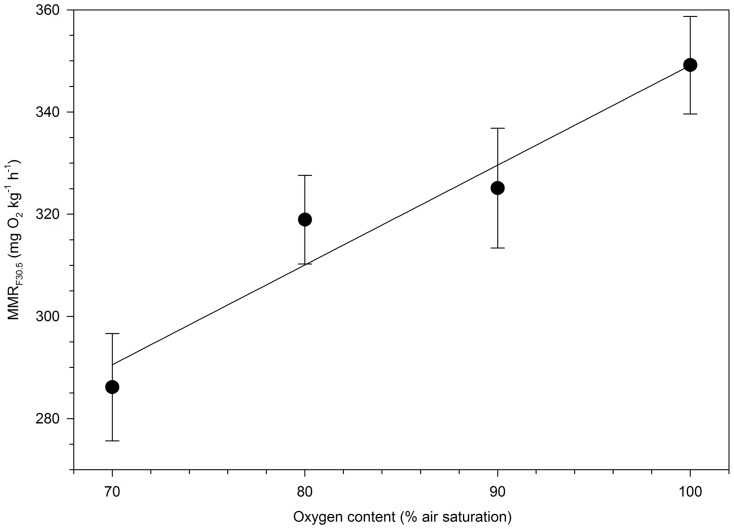

MMRF30.5 was quantified in four separate groups of A. fulvescens exposed to 100%, 90%, 80% or 70% O2sat to estimate the effect of hypoxia on MMRF30.5. Body mass did not differ between the four treatments (P = 0.95). MMRF30.5 was affected by hypoxia and decreased across the range from 100% O2sat to 70% O2sat (Fig. 4) as revealed by the linear regression analysis (P<0.03; r2>0.94). These findings indicated that the maximum metabolic rate of A. fulvescens is sensitive to increasing levels of hypoxia.

Figure 4. Forced maximum metabolic rate (MMRF30.5) is influenced by hypoxia in lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens.

Measurements of MMRF30.5 are body mass adjusted to a 30.5 g fish. MMRF30.5 decreased significantly across the range from 100% O2sat to 70% O2sat (P<0.03; r2>0.94).

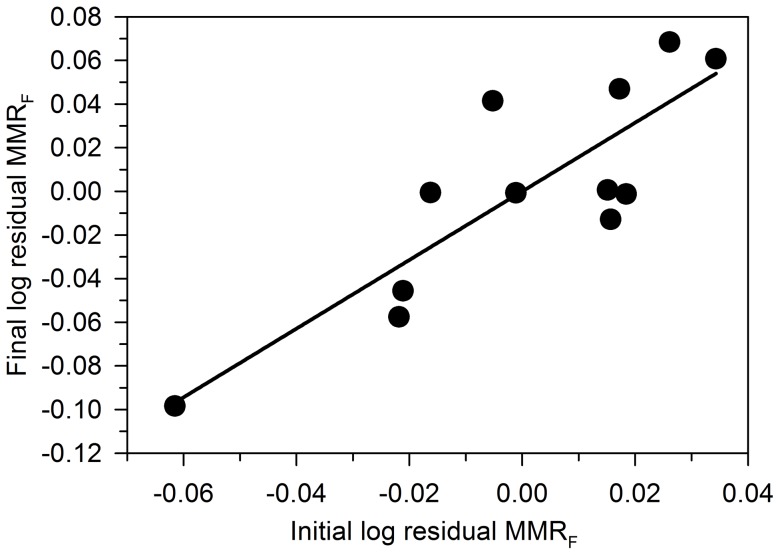

Repeatability of forced maximum metabolic rates (MMRF)

Analysis of repeatability followed a previous study [3] and showed that measurements of residual body mass corrected MMRF are repeatable in individual fish. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) for the relationship between the initial and final residual MMRF was 0.76, and the relationship was highly significant (P<0.006) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Forced maximum metabolic rate (MMRF) is repeatable in individual lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens.

Spearman's rank statistics were used to test for correlations between initial and final residual (i.e. body mass corrected) maximum metabolic rate (residual MMRF; mg O2 h−1) measured in individual A. fulvescens. The significant relationship (P<0.006; ρ = 0.76) indicates repeatability of MMRF. Time interval between initial and final measurements was 4.50 h.

Spontaneous maximum metabolic rate (MMRS)

MMRS was extracted from each 24 h trial for comparisons between test groups. MMRS differed significantly between all three test groups (P<0.05) (Table 1). These findings showed that MMRS was suppressed in treatments A and B, with the most pronounced effect in treatment A (Table 1). Standardizing MMRS to a 30.5 g fish using a 0.9 body mass scaling coefficient (i.e. equivalent to MMRF30.5) changed MMRS values by < 1% and had no impact on the conclusions.

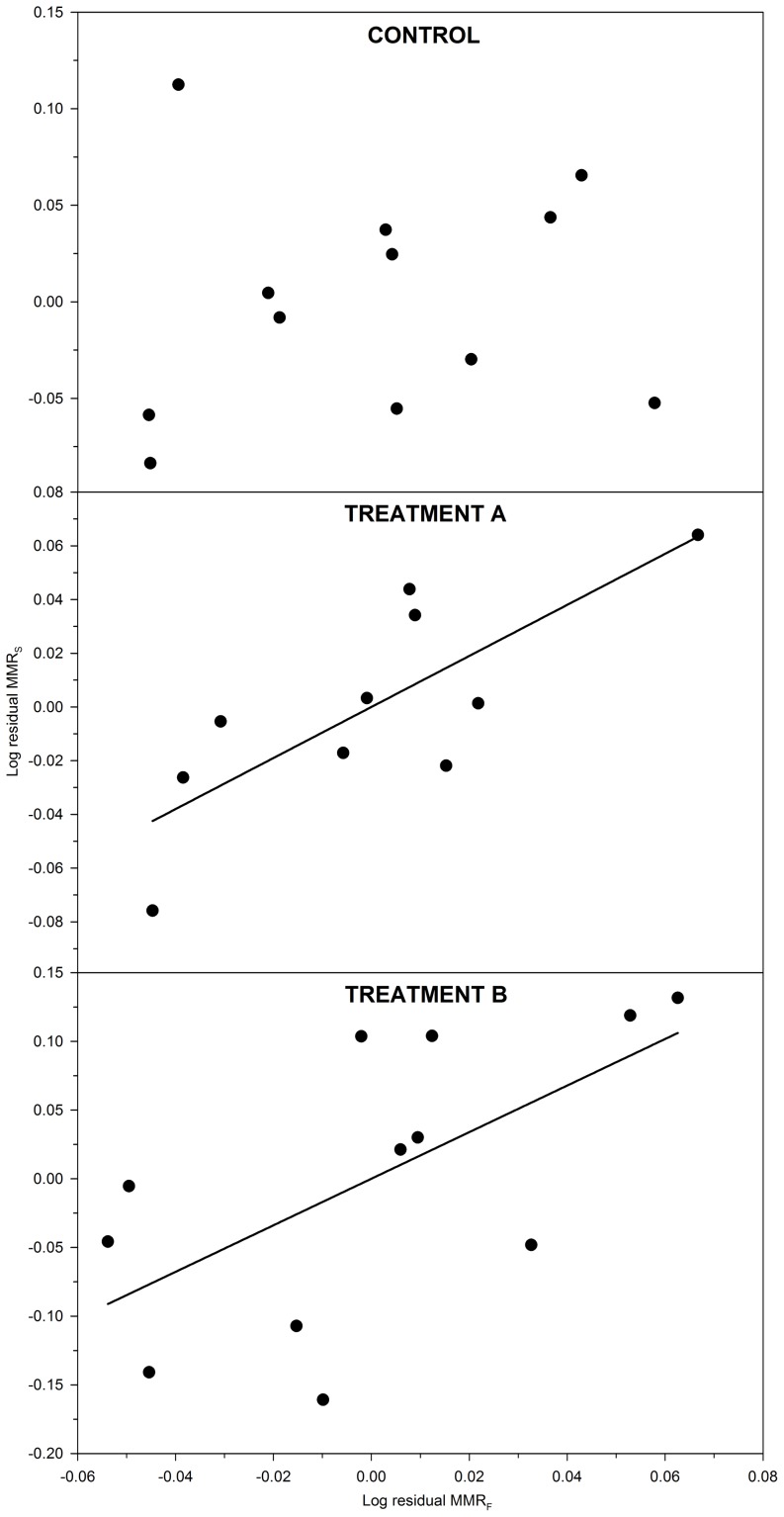

Correlations between forced (MMRF) and spontaneous (MMRS) maximum metabolic rates

MMRF and MMRS were compared to test the hypothesis that they would correlate positively. Data showed that residual MMRF and residual MMRS were not correlated in the control group (P = 0.40; ρ = 0.27) (Fig. 6, control). In contrast, residual MMRF and residual MMRS were positively correlated in both treatments A (P<0.05; ρ = 0.69) and B (P<0.05; ρ = 0.66) (Fig. 6, treatments A and B). These data indicated that an individual with an unexpectedly high MMRF also has an unexpectedly high MMRS, at least when the individual is exposed to an environmental stressor, such as hypoxia (treatment A) or constant light (treatment B).

Figure 6. Relationships between forced and spontaneous maximum metabolic rates in lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens.

Data collection comprised three test groups: control (100% O2sat; 12L∶12D), treatment A (30% O2sat; 12L∶12D), and treatment B (100% O2sat; 24L). Spearman's rank statistics were used to test for correlations between forced (MMRF) and spontaneous (MMRS) residual (i.e. body mass corrected) maximum metabolic rate (mg O2 h−1) measured in individual A. fulvescens. In the control group, there was no significant relationship between the residuals (P = 0.40; ρ = 0.27). In contrast, the residuals correlated positively in both treatments A and B (both P<0.05; ρ≥0.66).

Discussion

This study provides evidence that the organismal physiology of A. fulvescens is influenced by a circadian rhythm and strongly indicates that A. fulvescens is an oxygen regulator. Using residual (i.e. body mass corrected) values, the study suggests that MMRF is repeatable in individual A. fulvescens, and MMRF can be positively correlated with MMRS. The relationship between MMRF and MMRS appears, however, to depend on the presence of an environmental stressor such as hypoxia or constant light.

Our data indicated the presence of two metabolic peaks in A. fulvescens occurring over 24 h (Fig. 1). The first metabolic peak occurred around dusk (control group and treatment A), whereas the second metabolic peak occurred around dawn (treatments A and B) (Fig. 1). The dusk metabolic peak was eliminated by the constant light in treatment B, suggesting that the dusk metabolic peak reflected an exogenous rhythm, depending on exogenous stimuli (i.e. decreasing light levels). In contrast, the dawn metabolic peak occurred regardless of constant light, suggesting that a circadian rhythm, including an endogenous mechanistic basis, control the metabolic rate of A. fulvescens. As far as is known, our study provides the first evidence of a circadian rhythm in Acipenserids. It is not clear why the dawn metabolic peak was not distinct in the control group (Fig. 1). We suggest that the relatively high metabolic rates masked the dawn metabolic peak in the control group. In the hypoxic treatment, metabolic rates were suppressed, but not to an extent where the dawn metabolic peak was eliminated (Fig. 1). Therefore, the metabolic suppression in hypoxia helped revealing the underlying presence of two metabolic peaks.

In a recent field study, Forsythe et al. [50] reported that adult A. fulvescens initiate upstream migration around dusk and dawn. The authors suggested that the observations could ultimately be explained by reduced risk of predation and harvest by humans at dusk and dawn [50]. While the present study used juvenile A. fulvescens, our data indicate that the migratory peaks at dusk and dawn observed by Forsythe et al. [50] could reflect proximate mechanisms that include an exogenous rhythm at dusk and a circadian rhythm at dawn.

This study tested the hypothesis that A. fulvescens is an oxygen regulator. Our data provide two lines of evidence that A. fulvescens is an oxygen regulator, capable of regulating metabolic rate and maintaining metabolic rhythms in environmental hypoxia. Firstly, we found no evidence that SMR differed between normoxia and hypoxia (30% O2sat) (Table 1). Thus, A. fulvescens maintained SMR regardless of fluctuating environmental oxygen levels. Secondly, A. fulvescens exposed to hypoxia (30% O2sat) exhibited a similar metabolic rate rhythm over the time interval from 16 h to 23 h as A. fulvescens exposed to normoxia and was capable of increasing the metabolic rate around dusk in the hypoxic environment (Fig. 1, treatment A). The metabolic increase had a strong behavioural component in both hypoxia and normoxia, and correlated positively with the frequency of body undulations with tail excursions>90° (Fig. 3). These data show that A. fulvescens is capable of regulating metabolic rate (SMR) and maintaining metabolic rhythms in hypoxia. Thus, A. fulvescens is an oxygen regulator, like most teleost fishes.

In contrast to SMR, data indicated that MMRF30.5 is sensitive to increasing levels of hypoxia in A. fulvescens (Fig. 4). Physiologically, the result is expected because if a fish is exercising at MMR before the hypoxic exposure, compensatory mechanisms (e.g. increasing gill ventilation and cardiac output) are already utilized to support the elevated oxygen requirements and are unavailable to compensate for environmental hypoxia. The result is not, however, consistent with previous studies on teleost fish. Most previous studies have reported that the maximum metabolic rate in normoxia is maintained in low levels of hypoxia [21], [22], [41], typically down to approximately 80% O2sat. The reason for the discrepancy between the present and previous studies remains unknown, but is it possible the maximum metabolic rate of A. fulvescens is more sensitive to low levels of hypoxia than in most teleost fishes. Further tests comparing Acipenserids and teleost fishes using identical equipment and experimental approaches are required to examine the discrepancy.

Previous studies have demonstrated that SMR and MMR are repeatable physiological traits in a wide range of taxa [2]. Repeatability (or temporal consistency) is important when ascribing certain properties to an individual animal on the basis of a single physiological measurement [3]. Repeatability indexes the reliability of the protocol used to measure a trait [51] and further sets a general upper limit to the intensity of selection that can be applied to the trait [52]. If a trait is not repeatable over time, a single measure of the trait may not be representative of future physiological performance and it becomes unlikely that natural selection can act on the trait, i.e. separate the favoured from disfavoured individuals [53]. Little is known about repeatability of traits in Acipenserids, but a recent behavioural study [54] demonstrated that spawning times and locations are highly repeatable in mature A. fulvescens. To our knowledge, the present study provides the first estimate of physiological repeatability in Acipenserids. Our data suggest that body mass corrected measurements of MMRF are repeatable in A. fulvescens (Fig. 5), at least over short time intervals (4.5 h) and set the stage for studies examining repeatability over longer time intervals.

Recently, it has been shown that not only SMR and MMR, but also routine metabolic rate (RMR) can be a repeatable trait in fish [55]. Repeatability of RMR suggests that the spontaneous activity within a respirometer is not simply random bouts of movement over time, but rather, that individual fish exhibit consistent behavioural patterns when evaluated at different times [55]. The present study tested whether body mass corrected values of MMRF and MMRS are positively correlated to examine whether an unexpectedly high value of MMRF would indicate an unexpectedly high value of MMRS. By demonstrating positive relationships between MMRF and MMRS in A. fulvescens exposed to an environmental stressor (Fig. 6), the present study adds to the growing body of evidence indicating that variation in metabolism, as determined over time in a respirometer, is not random, but may reflect physiological or behavioural traits in individual animals.

Measurements of physiological performance, including MMRF and critical swimming speed (U crit), are widely used whole-organism indicators of maximal performance, examined to better understand evolutionary and physiological ecology [3], [53], [56]–[61]. While maximal performance is crucial for a wide range of behaviours tightly connected to fitness (e.g. [62], [63]), animals may not exercise at maximal intensity very often [64]–[66]. Therefore, measurements of maximal performance could have more pronounced functional importance if maximal performance correlated positively with spontaneous performance, which is used more frequently. In particular, this is important because selection regimes may not only operate on a trait's maximal value, but alternatively on the spontaneous use of the trait (i.e. ecological performance [37], [38]). In the present study, we examined maximal forced and spontaneous performances by measuring MMRF and MMRS to test whether the two traits are correlated. Considering treatments A and B, data indicated that A. fulvescens exhibiting an unexpectedly high MMRF also exhibit an unexpectedly high MMRS (Fig. 6). These data suggest that MMRF may be indicative of MMRS in individual A. fulvescens. Nevertheless, we only found relationships between MMRF and MMRS when fish were exposed to an environmental stressor (hypoxia or 24 h light), and no relationship when fish were exposed to normoxia and a normal light regime (12L∶12D) (Fig. 6).

It remains unclear why we observed relationships between MMRF and MMRS when A. fulvescens were exposed to an environmental stressor, and no relationship without an environmental stressor (Fig. 6). Our findings are, however, consistent with a recent review by Killen et al. [1]. The authors described how environmental stressors, including hypoxia and light, may either reveal or mask relationships between behaviour and physiology. Because we found evidence of correlations between behaviour and metabolic rate (Fig. 3), it is likely that MMRS not only reflected a physiological trait, but also a behavioural trait. As such, our relationships between MMRF and MMRS (Fig. 6) could be considered relationships between physiology and behaviour that were revealed by environmental stressors, as suggested by Killen et al. [1]. All our measurements of MMRF were stressful for A. fulvescens [46], [67], whereas the measurements of MMRS were probably most stressful under hypoxia and constant light. Physiological stress is associated with increased concentrations of plasma cortisol in Acipenserids [67]–[69] with secondary responses involving metabolism [70]. In the present study, MMRS was suppressed in treatments A and B (Table 1), and stress experienced by A. fulvescens under hypoxia and constant light could have influenced the relative distribution of phenotypes with regard to MMRS, such that positive correlations between MMRF and MMRS were revealed in treatments A and B (see Fig. 1 in Killen et al. [1]). This remains speculation, however, and further studies of the coupling between behaviour and physiology in divergent environments are needed to evaluate the hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Renault at the University of Manitoba for the light sensor. We thank Dr. G. R. Ultsch for advice concerning body mass adjustments of oxygen consumption rates. We thank T. Smith and the animal care staff at the University of Manitoba for assistance in the care and maintenance of experimental animals. We thank an anonymous reviewer and academic editor Dr. E. V. Thuesen for helpful and constructive comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

Funding in support of this research was provided to WGA by Manitoba Hydro (http://www.hydro.mb.ca/) and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant (http://www.nserc-crsng.gc.ca/professors-professeurs/grants-subs/dgigp-psigp_eng.asp) (Number 311909) in Canada. This research was partially supported by a grant (SFRH/BPD/89473/2012) from the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT; http://www.fct.pt/index.phtml.pt) in Portugal to JCS. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Killen SS, Marras S, Metcalfe NB, McKenzie DJ, Domenici P (2013) Environmental stressors alter relationships between physiology and behaviour. Trends Ecol Evol 28: 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. White CR, Schimpf NG, Cassey P (2013) The repeatability of metabolic rate declines with time. J Exp Biol 216: 1763–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Norin T, Malte H (2011) Repeatability of standard metabolic rate, active metabolic rate and aerobic scope in young brown trout during a period of moderate food availability. J Exp Biol 214: 1668–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boujard T, Leatherland JF (1992) Circadian rhythms and feeding time in fishes. Environ Biol Fishes 35: 109–131. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peyric E, Moore HA, Whitmore D (2013) Circadian clock regulation of the cell cycle in the zebrafish intestine. PLoS One 8: e73209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coppack T, Bairlein F (2011) Circadian control of nocturnal songbird migration. J Ornithol 152: 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reebs SG (2002) Plasticity of diel and circadian activity rhythms in fishes. Rev Fish Biol Fish 12: 349–371. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beale A, Guibal C, Tamai TK, Klotz L, Cowen S, et al. (2013) Circadian rhythms in Mexican blind cavefish Astyanax mexicanus in the lab and in the field. Nat Commun 4: 2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ross LG, McKinney RW (1988) Respiratory cycles in Oreochromis niloticus (L.), measured using a six-channel microcomputer-operated respirometer. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A 89: 637–643. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim WS, Kim JM, Yi SK, Huh HT (1997) Endogenous circadian rhythm in the river puffer fish Takifugu obscurus . Mar Ecol Prog Ser 153: 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Priede IG (1985) Metabolic scope in fishes. In: Tytler P, Calow P, editors. Fish energetics. Netherlands: Springer.pp. 33–64.

- 12. Pollock MS, Clarke LMJ, Dube MG (2007) The effects of hypoxia on fishes: from ecological relevance to physiological effects. Environ Rev 15: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu RSS (2002) Hypoxia: from molecular responses to ecosystem responses. Mar Pollut Bull 45: 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin PA (2013) Dissolved oxygen criteria for freshwater fish in New Zealand: a revised approach. New Zeal J Mar Fresh: In press. Doi:10.1080/00288330.2013.827123.

- 15.Hughes GM (1981) Effects of low oxygen and pollution on the respiratory systems of fish. In: Pickering AD, editor. Stress and Fish. New York: Academic Press.pp. 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ultsch GR, Jackson DC, Moalli R (1981) Metabolic oxygen conformity among lower vertebrates: The toadfish revisited. J Comp Physiol B 142: 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Virani NA, Rees BB (2000) Oxygen consumption, blood lactate and inter-individual variation in the gulf killifish, Fundulus grandis, during hypoxia and recovery. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 126: 397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry SF, Jonz MG, Gilmour KM (2009) Oxygen sensing and the hypoxic ventilatory response. In: Richards J, Farrell AP, Brauner C, editors. Fish physiology. Vol. 27. Hypoxia.San Diego CA: Academic Press, Vol. 27 .pp. 193–253. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kearney MR, White CR (2012) Testing metabolic theories. Am Nat 180: 546–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Urbina MA, Glover CN, Forster ME (2012) A novel oxyconforming response in the freshwater fish Galaxias maculatus . Comp Biochem Physiol Part A 161: 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrell AP, Richards JG (2009) Defining hypoxia: an integrative synthesis of the responses of fish to hypoxia. In: Richards JG, Farrell AP, Brauner CJ, editors. Fish physiology. Vol. 27. Hypoxia.San Diego CA: Academic Press, Vol. 27 .pp. 487–503. [Google Scholar]

- 22. McBryan TL, Anttila K, Healy TM, Schulte PM (2013) Responses to temperature and hypoxia as interacting stressors in fish: implications for adaptation to environmental change. Integr Comp Biol 53: 648–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ruer PM, Cech JJ, Doroshov SI (1987) Routine metabolism of the white sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanus: Effect of population density and hypoxia. Aquaculture 62: 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Randall DJ, McKenzie DJ, Abrami G, Bondiolotti GP, Natiello F, et al. (1992) Effects of diet on the responses to hypoxia in sturgeon (Acipenser Naccarii). J Exp Biol 170: 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nonnotte G, Maxime V, Truchot JP, Williot P, Peyraud C (1993) Respiratory responses to progressive ambient hypoxia in the sturgeon, Acipenser baeri . Respir Physiol 91: 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crocker CE, Cech Jr JJ (2002) The effects of dissolved gases on oxygen consumption rate and ventilation frequency in white sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanus . J Appl Ichthyol 18: 338–340. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burggren WW, Randall DJ (1978) Oxygen uptake and transport during hypoxic exposure in the sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus. Respir Physiol 34: 171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crocker CE, Cech Jr JJ (1997) Effects of environmental hypoxia on oxygen consumption rate and swimming activity in juvenile white sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanus, in relation to temperature and life intervals. Environ Biol Fishes 50: 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- 29. McKenzie DJ, Piraccini G, Steffensen JF, Bolis CL, Bronzi P, et al. (1995) Effects of diet on spontaneous locomotor activity and oxygen consumption in Adriatic sturgeon (Acipenser naccarii). Fish Physiol Biochem 14: 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cech Jr JJ, Crocker CE (2002) Physiology of sturgeon: effects of hypoxia and hypercapnia. J Appl Ichthyol 18: 320–324. [Google Scholar]

- 31. McKenzie DJ, Steffensen JF, Korsmeyer K, Whiteley NM, Bronzi P, et al. (2007) Swimming alters responses to hypoxia in the Adriatic sturgeon Acipenser naccarii . J Fish Biol 70: 651–658. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Biro PA, Stamps JA (2010) Do consistent individual differences in metabolic rate promote consistent individual differences in behavior? Trends Ecol Evol 25: 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burton T, Killen SS, Armstrong JD, Metcalfe NB (2011) What causes intraspecific variation in resting metabolic rate and what are its ecological consequences? P Roy Soc Lond B Bio 278: 3465–3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Niitepõld K, Hanski I (2013) A long life in the fast lane: positive association between peak metabolic rate and lifespan in a butterfly. J Exp Biol 216: 1388–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brett JR (1964) The respiratory metabolism and swimming performance of young sockeye salmon. J Fish Res Board Canada 21: 1183–1226. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cutts CJ, Metcalfe NB, Taylor AC (2002) Juvenile Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) with relatively high standard metabolic rates have small metabolic scopes. Funct Ecol 16: 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Husak JF (2006) Does survival depend on how fast you can run or how fast you do run? Funct Ecol 20: 1080–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Irschick D, Bailey JK, Schweitzer JA, Husak JF, Meyers JJ (2007) New directions for studying selection in nature: studies of performance and communities. Physiol Biochem Zool 80: 557–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Behrens JW, Steffensen JF (2007) The effect of hypoxia on behavioural and physiological aspects of lesser sandeel, Ammodytes tobianus (Linnaeus, 1785). Mar Biol 150: 1365–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Steffensen JF (1989) Some errors in respirometry of aquatic breathers: how to avoid and correct for them. Fish Physiol Biochem 6: 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Svendsen JC, Steffensen JF, Aarestrup K, Frisk M, Etzerodt A, et al. (2012) Excess posthypoxic oxygen consumption in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): recovery in normoxia and hypoxia. Can J Zool 90: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schurmann H, Steffensen JF (1997) Effects of temperature, hypoxia and activity on the metabolism of juvenile Atlantic cod. J Fish Biol 50: 1166–1180. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Svendsen JC, Tudorache C, Jordan AD, Steffensen JF, Aarestrup K, et al. (2010) Partition of aerobic and anaerobic swimming costs related to gait transitions in a labriform swimmer. J Exp Biol 213: 2177–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Svendsen JC, Banet AI, Christensen RHB, Steffensen JF, Aarestrup K (2013) Effects of intraspecific variation in reproductive traits, pectoral fin use and burst swimming on metabolic rates and swimming performance in the Trinidadian guppy (Poecilia reticulata). J Exp Biol 216: 3564–3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jones EA, Lucey KS, Ellerby DJ (2007) Efficiency of labriform swimming in the bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus). J Exp Biol 210: 3422–3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kieffer JD, Wakefield AM, Litvak MK (2001) Juvenile sturgeon exhibit reduced physiological responses to exercise. J Exp Biol 204: 4281–4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Allen PJ, Cech Jr JJ (2007) Age/size effects on juvenile green sturgeon, Acipenser medirostris, oxygen consumption, growth, and osmoregulation in saline environments. Environ Biol Fishes 79: 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jordan AD, Steffensen JF (2007) Effects of ration size and hypoxia on specific dynamic action in the cod. Physiol Biochem Zool 80: 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mayfield RB, Cech Jr JJ (2004) Temperature effects on green sturgeon bioenergetics. Trans Am Fish Soc 133: 961–970. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Forsythe PS, Scribner KT, Crossman JA, Ragavendran A, Baker EA, et al. (2012) Environmental and lunar cues are predictive of the timing of river entry and spawning-site arrival in lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens . J Fish Biol 81: 35–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Losos JB, Creer DA, Schulte JA (2002) Cautionary comments on the measurement of maximum locomotor capabilities. J Zool 258: 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Irschick DJ, Meyers JJ, Husak JF, Le Galliard J-F (2008) How does selection operate on whole-organism functional performance capacities? A review and synthesis. Evol Ecol Res 10: 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Oufiero CE, Garland Jr T (2009) Repeatability and correlation of swimming performances and size over varying time-scales in the guppy (Poecilia reticulata). Funct Ecol 23: 969–978. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Forsythe PS, Crossman JA, Bello NM, Baker EA, Scribner KT (2012) Individual-based analyses reveal high repeatability in timing and location of reproduction in lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens). Can J Fish Aquat Sci 69: 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Boldsen MM, Norin T, Malte H (2013) Temporal repeatability of metabolic rate and the effect of organ mass and enzyme activity on metabolism in European eel (Anguilla anguilla). Comp Biochem Physiol Part A 165: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Odell JP, Chappell MA, Dickson KA (2003) Morphological and enzymatic correlates of aerobic and burst performance in different populations of Trinidadian guppies Poecilia reticulata . J Exp Biol 206: 3707–3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chappell M, Odell J (2004) Predation intensity does not cause microevolutionary change in maximum speed or aerobic capacity in trinidadian guppies (Poecilia reticulata Peters). Physiol Biochem Zool 77: 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Oufiero CE, Walsh MR, Reznick DN, Garland Jr T (2011) Swimming performance trade-offs across a gradient in community composition in Trinidadian killifish (Rivulus hartii). Ecology 92: 170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dalziel AC, Schulte PM (2012) Correlates of prolonged swimming performance in F2 hybrids of migratory and non-migratory threespine stickleback. J Exp Biol 215: 3587–3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dalziel AC, Ou M, Schulte PM (2012) Mechanisms underlying parallel reductions in aerobic capacity in non-migratory threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) populations. J Exp Biol 215: 746–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dalziel AC, Vines TH, Schulte PM (2011) Reductions in prolonged swimming capacity following freshwater colonization in multiple threespine stickleback populations. Evolution 66: 1226–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Walker JA, Ghalambor CK, Griset OL, McKenney D, Reznick DN (2005) Do faster starts increase the probability of evading predators? Funct Ecol 19: 808–815. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Langerhans RB (2009) Morphology, performance, fitness: functional insight into a post-Pleistocene radiation of mosquitofish. Biol Lett 5: 488–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Irschick DJ, Herrel A, Vanhooydonck B, Huyghe K, Van Damme R (2005) Locomotor compensation creates a mismatch between laboratory and field estimates of escape speed in lizards: a cautionary tale for performance-to-fitness studies. Evolution 59: 1579–1587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pagan DNM, Gifford ME, Parmerlee Jr JS, Powell R (2012) Ecological performance in the actively foraging lizard Ameiva ameiva (Teiidae). J Herpetol 46: 253–256. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wilson AM, Lowe JC, Roskilly K, Hudson PE, Golabek KA, et al. (2013) Locomotion dynamics of hunting in wild cheetahs. Nature 498: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lankford SE, Adams TE, Miller RA, Cech Jr JJ (2005) The cost of chronic stress: impacts of a nonhabituating stress response on metabolic variables and swimming performance in sturgeon. Physiol Biochem Zool 78: 599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lankford SE, Adams TE, Cech Jr JJ (2003) Time of day and water temperature modify the physiological stress response in green sturgeon, Acipenser medirostris . Comp Biochem Physiol Part A 135: 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Baker DW, Wood AM, Kieffer JD (2005) Juvenile atlantic and shortnose sturgeons (family: Acipenseridae) have different hematological responses to acute environmental hypoxia. Physiol Biochem Zool 78: 916–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Barton BA (2002) Stress in fishes: A diversity of responses with particular reference to changes in circulating corticosteroids. Integr Comp Biol 42: 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]