Abstract

In January 2010, porcine circovirus type 1 (PCV1) DNA was unexpectedly detected in the oral live-attenuated human rotavirus vaccine, Rotarix™ (GlaxoSmithKline [GSK] Vaccines) by an academic research team investigating a novel, highly sensitive analysis not routinely used for adventitious agent screening. GSK rapidly initiated an investigation to confirm the source, nature and amount of PCV1 in the vaccine manufacturing process and to assess potential clinical implications of this finding. The investigation also considered the manufacturer’s inactivated poliovirus (IPV)-containing vaccines, since poliovirus vaccine strains are propagated using the same cell line as the rotavirus vaccine strain. Results confirmed the presence of PCV1 DNA and low levels of PCV1 viral particles at all stages of the Rotarix™ manufacturing process. PCV type 2 DNA was not detected at any stage. When tested in human cell lines, productive PCV1 infection was not observed. There was no immunological or clinical evidence of PCV1 infection in infants who had received Rotarix™ in clinical trials. PCV1 DNA was not detected in the IPV-containing vaccine manufacturing process beyond the purification stage. Retrospective testing confirmed the presence of PCV1 DNA in Rotarix™ since the initial stages of its development and in vaccine lots used in clinical studies conducted pre- and post-licensure. The acceptable safety profile observed in clinical trials of Rotarix™ therefore reflects exposure to PCV1 DNA. The investigation into the presence of PCV1 in Rotarix™ could serve as a model for risk assessment in the event of new technologies identifying adventitious agents in the manufacturing of other vaccines and biological products.

Keywords: Rotarix™, adventitious agents, human rotavirus vaccine, inactivated poliovirus vaccine, porcine circovirus type 1

Introduction

In January 2010, an academic research team, investigating novel technology not routinely used for adventitious agent screening (massively parallel sequencing), discovered the unexpected presence of porcine circovirus type 1 (PCV1) DNA in the oral live-attenuated human rotavirus vaccine, Rotarix™ (GlaxoSmithKline [GSK] Vaccines).1 GSK immediately confirmed this finding and informed regulatory authorities, which led to the vaccine being temporarily suspended from the market in some countries as a precautionary measure. Since live-attenuated viral vaccines are propagated in cultured cell lines and animal-derived raw materials are often used in their manufacturing, unintentional introduction of adventitious agents is a recognized potential concern. Guidelines are in place to reduce the risk of introduction of adventitious agents during vaccine manufacturing processes,2 and Rotarix™ has always been manufactured in compliance with relevant guidance and regulations.

Rotavirus is the most common cause of acute gastroenteritis in infants and young children worldwide. Rotavirus gastroenteritis accounts for approximately half a million deaths annually among children younger than 5 y of age, with the great majority of these deaths occurring in low-income countries.3–5 Vaccination is considered to be the most effective public health strategy to prevent rotavirus infection and reduce disease burden, and the World Health Organization recommends the inclusion of rotavirus vaccination into all national infant immunization programmes.6 In low-income countries, universal rotavirus vaccination has the potential to prevent 2.4 million deaths over the next two decades.5 Rotarix™ has been shown to be efficacious for the prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis in large-scale, randomized, controlled clinical trials conducted in Latin America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Japan.7–13 Following its first licensure in Mexico in 2004, Rotarix™ has been licensed in more than 123 countries worldwide, including in the United States in April 2008. Rotarix™ was the first rotavirus vaccine to be prequalified by the World Health Organization for use by international agencies in mass vaccination programs.

Following notification of the detection of PCV1 DNA in Rotarix™, GSK rapidly initiated an investigation to confirm the nature, source and amount of PCV1 in the vaccine manufacturing process and to assess the potential clinical implications of this finding. This investigation also considered the manufacturer’s inactivated poliovirus (IPV)-containing vaccines, since the poliovirus vaccine strains and the rotavirus vaccine strain are both propagated using the same African green monkey kidney-derived Vero cell line. GSK collaborated with experts in porcine viruses and analytical detection methods, as well as several regulatory agencies, including the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This paper reviews the investigation conducted by GSK and its findings. The investigation was designed to answer four specific questions: (1) Was PCV1 DNA in the vaccine associated with the presence of viral particles? (2) Were PCV1 particles in the vaccine capable of infecting permissive cells? (3) Were PCV1 particles in the vaccine capable of productive infection in human cells? (4) Were PCV1 particles in the vaccine capable of causing infection in vaccine recipients?

Results

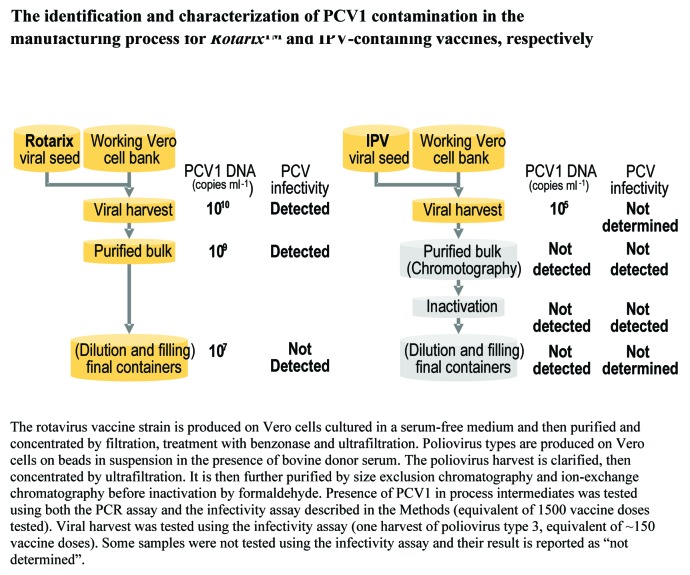

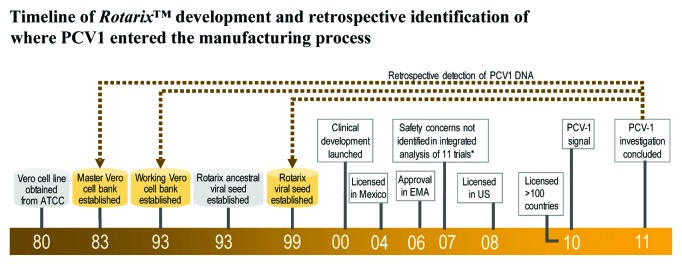

Extent of PCV1 DNA presence in the vaccine manufacturing process

Figure S1 provides an overview of the Rotarix™ and IPV-containing vaccine manufacturing processes. Within the Rotarix™ vaccine manufacturing process, PCV1 DNA was detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR) in the viral harvest, purified bulk and final container at concentrations of 1010, 109, and 107 DNA copies/ml, respectively (Fig. 1). A total of 4 samples from the viral harvest, 2 samples from the purified bulk and 334 samples from the final container were tested. PCV1 DNA was also detected in single samples from the master and working Vero cell banks that date from 1983 and 1993, respectively, as well as in a single sample from the Rotarix™ viral seed established in 1999 (Fig. 2). Respective PCV1 DNA concentrations in the Vero working cell bank and the Rotarix™ viral seed were approximately 1.1 copy/Vero cell and 1011 copies/ml.

Figure 1. The identification and characterization of PCV1 contamination in the manufacturing process for Rotarix™ and IPV-containing vaccines, respectively.

Figure 2. Timeline of Rotarix™ development and retrospective identification of where PCV1 entered the manufacturing process.

Full genome sequencing confirmed at least 98% identity of the nucleotide sequence against other PCV1 strains deposited in the GenBank database. Seven major nucleotide changes were observed in Rotarix™-related samples when compared with the PCV1 sequences described in GenBank (1 single nucleotide polymorphism in the rep gene and 6 in the capsid gene) (Table 1). All seven mutations were observed as partial changes reflecting heterogeneity of the PCV1 viral population. PCV1 genome sequences were shown to be conserved between the Vero working cell bank, the rotavirus working seed, the intermediate process samples and the final Rotarix™ vaccine. Two specific mutations previously identified in the PCV1 capsid gene14 were also observed in Rotarix™-related samples when compared with unique versions described in the sequence databases: mutation A1163G encodes a partial amino acid change at residue 172 from an isoleucine to a threonine and mutation T1647G is silent.

Table 1. Conservation of PCV1 sequences through the Rotarix™ manufacturing process and in stool samples from vaccine recipients.

| Sample type |

Sample description | Nucleotide position* | Genome coverage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 222 | 997 | 1030 | 1163 | 1183 | 1420 | 1647 | |||

| Databases | PCV1 consensus | T G |

T C |

C | A | T C |

G T |

T | NA |

| Vero WCB | P136 1999/1 | G/T | T/C | C/t | G/A | T/c | G/T | T/G | 100% |

| Working seed | RVCL29G02 | T/g | T/c | C/t | G/a | T/c | G/T | G/t | 100% |

| Single harvest | AROTBHA003 | T/g | T/c | C/t | G/a | T/c | G/T | G/t | 100% |

| Clarified virus pool | AROTBVA007 | T/g | T/c | C/t | G/a | T/c | G/T | G/t | 100% |

| Final container | AROTA200A | T/G | T/c | C/t | G/A | T/c | G/T | G/T | 100% |

| Stool samples | 1 | T/g | T/c | C/t | G/a | T/c | G/t | G/t | 95% |

| 2 | T/G | T/c | C/t | G/a | T/c | G/t | G/T | 100% | |

| 3 | T/g | T/c | C/t | G/a | T/c | G/t | G/t | 100% | |

| 4 | ND | T C |

C T |

G A |

C | ND | ND | 47%** | |

| Codon change (complementary strand) | NA | NA | NA | ATT→ACT | NA | NA | AGA→CGA | ||

| Amino acid change | NA | NA | NA | I172T | NA | NA | R11R | ||

| PCV1 gene | Rep | Capsid | |||||||

ND, sequence not determined; NA, not applicable. *Nucleotide positions are based on the numbering defined from the PCV1 sequence published by Victoria et al. 20101 According to this numbering, mutations A222G and T706G (identified by Gilliland et al. 2012)14 are at position 1163 and 1647, respectively. **Sequencing was limited by the amount of recovered material. When the sequencing trace is mostly homogenous or a single nucleotide version is described, a single nucleotide is indicated. When different PCV1 sequences are described at a specific position, the different nucleotide versions are presented vertically. When multiple sequencing traces are detected, the different nucleotides are separated by a slash bar. The first nucleotide in upper case corresponds to the more abundant version. The second nucleotide in lower case is the less abundant. If mixed signals are at the same levels, both nucleotides are in upper case. Both specific variations A1163G and T1647G are presented in gray cases

PCV1 DNA was detected in 3 batches of vaccine used in pivotal prelicensure clinical studies in quantities similar to those in the commercially available vaccine. These findings confirmed that PCV1 DNA had been present since the early stages of vaccine development and that the safety database generated during pivotal prelicensure clinical studies reflected the safety profile of the commercially available product.

No PCV1 DNA was detected in the original cell line from 1980 or in the ancestor of the Rotarix™ viral seed (single samples of each).

For the IPV-containing vaccine manufacturing process, 1 sample from the Vero working cell bank, 3 samples from the monovalent working seeds, 2 samples from the monovalent viral harvests, 15 samples from each of the purified bulks (16 for poliovirus type 3), 3 samples from the monovalent inactivated bulks, 6 samples from the trivalent inactivated bulk, and 3 samples from the trivalent vaccine final container were tested. PCV1 DNA was only detected in the viral harvest and at a much lower concentration than in Rotarix™ (105-fold less) (Fig. 1). PCV-1 DNA load measured in the Vero working cell bank used for IPV vaccine manufacturing was shown to be lower (0.001 PCV1 DNA copies/cell) than the concentration measured in the Vero working cell bank used for Rotarix™ manufacturing (1.1 PCV1 DNA copies/cell). PCV1 DNA load in the 3 types of poliovirus working seeds was at least 5 log lower than that observed in the rotavirus working seed (~1011 PCV1 DNA copies/ml). PCV1 DNA was not detected in the purified bulk, inactivated bulk, or final container of the IPV-containing vaccine. A PCV1 DNA clearance factor of at least 104 was estimated for the purification step.

PCV2 DNA was not detected at any stage of the manufacturing process for either vaccine.

Infectivity in porcine and African green monkey cell lines

Infectious PCV1 was detected by inoculating permissive PCV1 negative porcine kidney (PK15) cells and Vero cells with a volume of Rotarix™ virus harvest and purified bulk equivalent to 1500 Rotarix™ vaccine doses. Cells were found PCV1 positive at the first time point tested (day 3 after inoculation) and during 2 additional passages, when it was decided to stop the subculture process. Subsequent experiments allowed the detection of PCV1 viral gene expression as early as day 3 after the inoculation of Vero and PK15 cells with the equivalent of 300 Rotarix™ doses, supporting the use of an inoculum of that size for the infectivity assays conducted on human cell lines. Titration assays were then conducted on Vero cells to estimate the PCV1 virus load in Rotarix™. The titer of infective PCV1 in Rotarix™ final container material, assuming no loss of virus in the downstream manufacturing process, was estimated to range between 0 and 100 CCID50 per dose.

Infectious PCV1 viral particles were not detected using the PK15 and Vero cell assays with the equivalent of 1500 doses from the purified and inactivated bulks of the IPV-containing vaccine. The cells remained PCV1 negative after the first 3 d inoculation and in all 5 sub-passages.

Infectivity in human cell lines

No viral expression or productive infection was detected following the incubation of PCV1-stock samples or the equivalent of 300 vaccine doses of Rotarix™ purified bulk with human MRC5 and U937 cell lines. Viral expression was transiently detected in the transformed human Hep2 cell line included as a positive control. The infection was considered non-productive since PCV1 viral gene expression became undetectable after the first or second passage of the infected Hep2 cells and because infectious PCV1 could not be detected in permissive PK15 cells inoculated with the supernatant collected from the infected Hep2 cells. These findings suggest that PCV1 associated with Rotarix™ does not induce productive infection in any of the tested human cell lines.

Infectivity in humans

PCV1 DNA was detected by Q-PCR in archived stool samples of 4/40 infants who received Rotarix™ in prelicensure clinical trials (Table 2). In all studies, PCV1 DNA was only detected in stool samples from the earliest post-vaccination time points (3 or 7 d post-dose 1) and PCV1 DNA was not detected at later time points for any infant. In all cases, PCV1 sequences were identical to the PCV1 sequence found in Rotarix™ (Table 1). These findings suggest that viral replication did not occur in the gastrointestinal tract, since viral replication would be expected to be associated with prolonged or persistent detection of PCV1 DNA in stool samples collected at later time points after vaccination and with nucleotide changes in the PCV1 genome. These results suggest the transient passage of PCV1 DNA in Rotarix™ through the gastrointestinal tract without viral replication. Of note, a PCV1 positive signal was raised by Q-PCR at day 15 in the stool sample of one infant who received placebo in these studies; however, the DNA sequence analysis was negative. Antibodies against PCV1 were not detected in serum samples obtained prior to vaccine administration and after administration of the last vaccine dose from any infants who received Rotarix™ in the same studies, including those who had PCV1 DNA detected in their stool samples. The pattern of adverse events reported in vaccinated infants with PCV1 DNA detected in their stool samples did not differ from that observed in placebo recipients (data not shown).

Table 2. Detection of PCV1 in individual recipients of Rotarix™.

| PCV1 detection by Q-PCRa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Day 0b | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 10 | Day 15 | Day 30 | Day 45 |

| 1 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | - | + | IC | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | - | NA | + | NA | - | NA | NA |

| 4 | - | NA | + | NA | - | NA | NA |

a Positive results confirmed by DNA sequencing. Third replicate evaluated if results of two replicates were equivocal. bStudy Day, Dose 1 was administered at Day 0. -, PCV1 not detected; +, PCV1 detected and sequence confirmed; IC, inconclusive; NA, sample not available.

No anti-PCV1 antibodies were detected in serum samples from subjects who received IPV-containing vaccines. Stool samples were not collected from these subjects since the IPV-containing vaccines were not administered orally.

Discussion

The emergence of new technologies will inevitably result in new challenges in the safety assessment of vaccines and other biological materials. Results of the investigation into the presence of PCV1 DNA in Rotarix™ confirm a low level of infective viral particles in the vaccine production process and in the final container material (estimated at 0–100 infectious particles per vaccine dose). However, there is no evidence that these viral particles can cause productive infection in humans. Retrospective analysis of serum and stool samples from infants who had received Rotarix™ showed no evidence of PCV1 infection in vaccinated infants. The related porcine virus PCV2 was not detected at any stage of the vaccine manufacturing process.

Our findings are in keeping with the results of other recent independent investigations, including the identification of two previously unidentified sequence polymorphisms in PCV1 DNA obtained from the vaccine.14–17 The determined range of infectious particles (0–100 per vaccine dose) is compatible with previous reports by two groups which did not detect infective PCV1 in Rotarix™,14,15 and a third group that was able to successfully infect PK15 and swine testes (ST) cells with a 1:100 dilution of a Rotarix™ dose.16 Porcine-derived trypsin appears to be the most likely source of the PCV1 DNA detected in Rotarix™. When the master cell bank was originally generated in 1983, porcine-derived trypsin was not routinely irradiated. Contaminated porcine-derived trypsin was found to be the source of the low-level contamination of PCV1 and PCV2 DNA fragments in another licensed live-attenuated rotavirus vaccine, RotaTeq™ (Merck Vaccines).18

It is unclear why the PCV1 DNA concentration was lower in the poliovirus harvest compared with the rotavirus harvest. It may be related to differences in exposure to contaminated porcine-derived trypsin during the preparation of the respective viral seeds or to differences in the culture process applied during the preparation of the respective cell banks, since PCV1 replication has been reported to be influenced by the cell culture parameters.16 The additional chromatographic purification and formaldehyde inactivation stages in the IPV-containing vaccine manufacturing process likely further contributed to a reduction in the amount of PCV1 DNA in the poliovirus purified bulk. Consequently, the lower initial PCV1 DNA viral load combined with this clearance factor resulted in PCV1 DNA levels below the limit of detection in the final product.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the presence of PCV1 in Rotarix™ to include retrospective testing of the master and working Vero cell banks, the Rotarix™ viral seed and batches of vaccine used in pivotal prelicensure clinical studies. Results confirmed the presence of PCV1 DNA in the Rotarix™ vaccine since the initial stages of its development and during pivotal prelicensure clinical trials. The safety data gathered from clinical trials and post-licensure therefore reflect exposure to PCV1 DNA. Results of an integrated clinical safety summary undertaken for 28 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase II and III trials of Rotarix™ involving over 100 000 infants show vaccine to have an overall safety and tolerability profile similar to that of placebo.19 The asymptomatic nature of PCV1 infection in its host species prevents a retrospective targeted interrogation of the Rotarix™ safety database. At the time of this investigation, more than 69 million doses of Rotarix™ had been distributed worldwide, with postmarketing surveillance data showing no signal of a safety risk attributable to the presence of PCV1 DNA in the vaccine.

The results of this investigation are consistent with published data concerning the lack of pathogenicity of PCV1 in pigs and humans,20–22 including individuals likely to be at high-risk of infection, such as veterinarians in swine practice.23 PCV1 infection is widespread among pigs21,24–26 and humans are frequently exposed to PCV1 through the dietary consumption of PCV1-infected pork products.27 However, PCV1 seems unable to productively infect human cell lines.28 The closely related virus PCV2 was not detected in either Rotarix™ or IPV-containing vaccines. PCV2 has been linked to postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome and other diseases in pigs,29–31 but there is currently no evidence supporting PCV2 pathogenicity in humans.22,23,28,32

Considerable reductions in hospital admissions and mortality due to rotavirus gastroenteritis and diarrhea of any cause in infants and young children have been reported following inclusion of Rotarix™ into global infant immunization schedules.33–52 Based on the findings of this investigation and information derived from their own investigation,16 the FDA determined that it was appropriate to resume use of Rotarix™ and the temporary marketing suspension of the vaccine was lifted within 2 mo of its initiation.53 The World Health Organization and the EMA concurred that the vaccine continues to have a positive benefit-risk balance and that the presence of a very small amount of PCV1 viral particles does not pose a risk to public health.54,55 Nevertheless, GSK is committed to evaluating the feasibility of manufacturing a PCV-free formulation of Rotarix™.

Conclusion

This investigation complements similar studies undertaken by independent groups including the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC). Our findings confirm the presence of low levels of PCV1 viral particles at all stages of the Rotarix™ manufacturing process. However, productive PCV1 infection was not observed in human cell lines, and there was no immunological or clinical evidence of PCV1 infection in infants who received Rotarix™ in clinical trials. Retrospective testing confirmed that PCV1 DNA had been present in Rotarix™ since its initial development. Safety data from prelicensure clinical trials therefore reflect exposure to vaccine containing PCV1 DNA, with results of these studies showing Rotarix™ to have a safety and tolerability profile similar to that of placebo. The investigation into the presence of PCV1 in Rotarix™ could serve as a model for risk assessment in the event of new technologies identifying adventitious agents in the manufacturing of other vaccines and biological products.

Methods

Investigation strategy

The strategy for this investigation into the presence of PCV1 in final batches of Rotarix™ was based on the approach taken in the late 1990s to characterize the contamination of live-attenuated measles and mumps vaccines with avian leukosis virus-derived reverse transcriptase.56,57

The first step of the investigation was to evaluate the extent and magnitude of the PCV1 DNA presence at each stage of the vaccine manufacturing process (Fig. S1) in order to identify the most likely source of the contamination. All stages of the vaccine manufacturing process and all source materials were screened using a Q-PCR assay capable of detecting both PCV1 and PCV2 (PCV1/2). The detected DNA was identified by full genome DNA sequencing. Archived vaccine lots used in Phase III studies of Rotarix™ (RCV018A42, RVC019A43, and RVC021A44) were also screened for the presence of PCV1 and PCV2 DNA in order to determine whether the adventitious agent had been present in the vaccine used during pivotal prelicensure clinical trials. Samples collected at different stages of the IPV-containing vaccine manufacturing process were also tested for the presence of PCV1/2 DNA. The second step of the investigation was to evaluate whether infectious PCV1 particles were present in either vaccine by incubating purified bulk of both Rotarix™ and IPV-containing vaccine onto the permissive PK15 cell line and assessing viral gene expression by reverse transcriptase Q-PCR. Infectivity assays were also conducted using a PCV1 negative Vero cell line.

The third step of the investigation was to evaluate whether PCV1 viral particles in the purified bulks of either vaccine were able to produce productive infection in human cells. Infectivity assays were performed on two human cell lines: MRC5 (a diploid human cell line) and U937 (a monocytic human cell line). The transformed human cell line Hep2 was included as a positive control, since PCV1 infection has been previously reported in transformed human hepatic cell lines.28

The fourth step of the investigation was to evaluate whether any PCV1 viral particles present in either vaccine were able to cause infection in humans. Blinded, retrospective laboratory evaluation of archived samples from four completed clinical trials of Rotarix™ was undertaken to assess for the presence of PCV1 DNA in stool samples and for evidence of serologic response to PCV1 following vaccination. Blinded, retrospective laboratory evaluation of archived samples from two completed clinical trials of GSK Biologicals’ IPV-containing vaccines was also undertaken to assess for evidence of serologic response to PCV1 following vaccination. Stool samples were not collected from subjects who received IPV-containing vaccines.

PCV1 DNA detection by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR)

A real-time PCR assay based on Taqman chemistry was used to detect and to quantify the number of PCV1 DNA copies present in the different vaccines and clinical materials. Nucleic acids were extracted from the vaccine materials using the QIAamp Viral RNA Kit (Qiagen) and from the cell-containing materials using the QIAamp DNA Kit (Qiagen). PCV1 DNA was extracted from stool samples using the MagNAPure system with High Pure Filter Tubes (Roche). The PCR primers and the Taqman probe are designed in a conserved region of the rep gene and are able to amplify a 73-bp product from both PCV1 and PCV2 DNA with the same efficiency. PCV1 DNA was amplified using the qPCR MasterMix Plus (Eurogentec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the following cycling parameters: 95 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles of 95 °C 15 s, 60 °C 1 min.

The number of PCV1 DNA copies per Q-PCR reaction was determined using a synthetic DNA template corresponding to a 77-base long single-stranded oligonucleotide. 10-fold serial dilutions of this synthetic calibrator were used to generate standard curves. The resulting Ct values for each amount of template were plotted as a function of the log (10) copy number. The number of PCV1 copies was expressed per milliliter or per gram when liquid vaccine materials or stool samples were considered, respectively. For the calculation of the number of PCV1 copies per cell, the number of cell equivalents involved per Q-PCR reaction was determined using the number of 18S RNA genes as calibrator.

The Q-PCR method used for the specific detection of PCV2 was as previously described.14

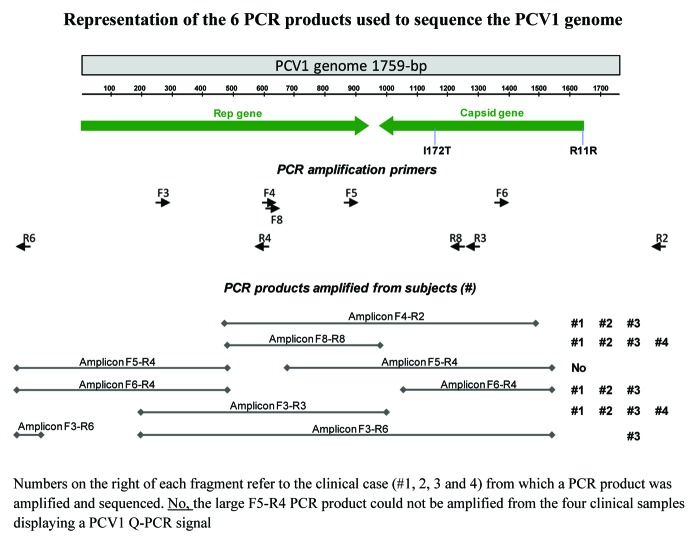

PCV1 DNA sequencing

Ten amplification primers were designed from PCV1 published sequences to generate 6 overlapping PCR products targeting the entire genome sequence (Table 3; Fig. 3). PCV1 sequences present in Rotarix™-related samples were derived from PCR products amplified using at least the primer pairs F4/R2 and F5/R4 (Fig. 3). PCV1 DNA detected in the 4 positive stool samples from vaccinated infants (Table 2) was sequenced according the strategy represented in Figure 3.

Table 3. Description of the primers used for PCR amplification and PCV1 DNA sequencing.

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Primer use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR amplification | DNA sequencing | ||

| PCV1_F2 | GGCAGCGGCA GCACCTC | X | |

| PCV1_F3 | TCCCTGTAAC GTATGTGAG | X | X |

| PCV1_F4 | GTGTGACCGG TATCCATTG | X | |

| PCV1_F5 | TTTGAAGCAG TGGACCCAC | X | X |

| PCV1_F6 | CAAGTTGGTG GAGGGGGTTA CA | X | X |

| PCV1_F7 | GGGGTTGGTG CCGCCTG | X | |

| PCV1_F8 | ATCCATTGAC TGTAGAGAC | X | X |

| PCV1_F9 | CCATATAAAA TAAATTACTG | X | |

| PCV1_F10 | GAGAAATTTC CGCGGGCTG | X | |

| PCV1_R1 | AGCAGCGCAC TTCTTTCACT TTT | X | |

| PCV1_R2 | CAGCGCACTT CTTTCACTT | X | X |

| PCV1_R3 | CAGCCCTTTA CCTACCACTC CAG | X | X |

| PCV1_R4 | CAATGGATAC CGGTCACAC | X | X |

| PCV1_R5 | GCTGCGCTTC CCCTGGTT | X | |

| PCV1_R6 | GTATTTTGTT TTTCTCCTCC TC | X | X |

| PCV1_R7 | ATCATCCCAA GGTAACCAG | X | |

| PCV1_R8 | TACTTCACCC CCAAACCTG | X | X |

| PCV1_R9 | GGAAGGATTA TTAAGGGTG | X | |

Figure 3. Representation of the 6 PCR products used to sequence the PCV1 genome.

Sequencing reactions were performed using the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator v3.0 Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems). The sequencing primers are described in Table 3.

Sequencing products were analyzed using the ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer. Sequence comparisons with wild type and vaccine PCV1 strains were performed on the full genome sequence and focused on the different nucleic acids which were determined as a signature of the PCV1 vaccine strain.

Detection and quantification of infective PCV1

The presence of infective PCV1 viral particles was assayed by incubation with the permissive PCV1 negative porcine kidney cell line PK15 (provided by Dr B Caij, Veterinary and Agrochemical Research Center) and the PCV1-negative African Green monkey Vero cell line (provided by Dr H Nauwynck, Ghent University, Belgium). The cells were grown in MEM medium containing 3% FBS (10% for PK15 cells), 0.1% neomycin, 0.1% gentamycin and 1% glutamine (complete MEM). PK15 and Vero cells in expansion phase and with a confluence of 50–80% were obtained by inoculating T175 flasks on the day before starting the infectivity assay.

The live human rotavirus (HRV) present in the Rotarix™ single harvest and purified bulks was neutralized before inoculation on PCV1-negative Vero or PK15 cells by incubation for 4 h at 37 °C with the two anti-HRV neutralizing monoclonal antibodies 2C9 and 5E8. The same two monoclonal antibodies were added to the MEM medium in all subsequent steps of the infectivity assay conducted with Rotarix™ single harvest or purified bulk. The live poliovirus type 1 present in the purified bulks was also neutralized before inoculation on Vero or PK15 cells. Neutralization consisted of two steps. First, the purified bulk was heated for 20 min at 56 °C, a condition that is known to inactivate poliovirus without affecting the infectious titer of PCV.58–60 Then putative residual poliovirus was neutralized by incubation for 2 h at 37 °C with the anti-polio neutralizing monoclonal antibody MAB425. MAB425 has been developed by the NIBSC and is specific for poliovirus type 1. The same monoclonal antibody was added to the MEM medium in all subsequent steps of the infectivity assay conducted with poliovirus type 1 purified bulks. The residual formaldehyde in the inactivated poliovirus bulks was neutralized by adding 1 volume of sodium bisulfite (0.08M) to 19 volumes of inactivated polio bulk and incubating for 15 min at room temperature (20–25 °C).

The 50–80% confluent Vero and PK15 T175 flasks were rinsed with complete MEM, inoculated with 25 ml of test sample and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Three positive controls were included in the assay. Each control contained 1000 CCID50 PCV1 (WEY P.18; provided by Dr J McNair, Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute) diluted with either complete MEM or complete MEM containing the anti-rotavirus monoclonal antibodies 2C9 and 5E8 or complete MEM containing the anti-poliovirus monoclonal antibody 425. After incubation for 2 h at 37 °C, the inoculum was removed, the cells were washed with complete MEM and 100 ml of complete MEM was added. Three to four days after inoculation at 37 °C, 2 × 10 ml of supernatant was collected from each flask. The residual medium was removed, each flask was washed with complete MEM and cells were dissociated with trypsin. One third of these cells were inoculated in new T175 flasks and two cell pellets each containing 2 × 106 cells were prepared and frozen at -80 °C for subsequent analysis by RT-PCR. Subsequent cell passages and sample collections were conducted every 3 to 4 d as described above. Cultures with a positive PCV1 infection for two consecutive passages were stopped, while cultures that remained PCV1-negative were passaged up to 5 times in the initial experiments. Since no culture associated with a negative PCV1 result became positive after the first and second passages, we decided to stop the subcultures after two passages.

The 2 × 106 cell pellets were subjected to RNA extraction using the High pure RNA kit (Roche) with DNase treatment. RNA was eluted in 50 µl elution buffer and treated with TurboDNase. Reverse transcription reactions were performed for each sample with Q script cDNA synthesis (Quanta). Briefly, 5 µl of RNA was reverse transcribed in a volume of 20 µl and incubated for 5 min at 22 °C, followed by 30 min at 42 °C and 5 min at 85 °C. Taqman Q-PCR directed against the Rep’ transcript was used, amplifying a 111bp fragment. The primers and probe used were as previously described.61 The Q-PCR was performed using the Gene Expression Master Mix (ABI), in a final volume of 25 µl containing 2.5 µl of cDNA. After 2 min at 50 °C and 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles were performed consisting of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. Detection of viral gene expression was considered indicative of positive infection. The assay proved to be highly specific and sensitive (1–10 CCID50).

As a variant of the infectivity assay, the titration assays were also conducted on the same PCV1-negative Vero cells grown in Biorich Medium containing 1% FBS in 96 well plates. Serial 10-fold dilutions of test samples were conducted in Biorich medium. Each dilution was inoculated (100 µl/well) in 10 different wells of sub-confluent Vero cells. Plates were incubated for 7 d at 37 °C. They were then washed with PBS and dried at 37 °C before storage at −70 °C. Cell monolayers were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, permeabilized with methanol in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and washed again. PCV1 specific staining was conducted in the laboratory of Dr H Nauwynck (Ghent University, Belgium) with a monospecific polyclonal antibody that had been obtained after inoculation of a gnotobiotic pig with the PCV1 strain CCL-33 and a goat anti-swine antibody conjugated to peroxidase. In a variant of this assay, permeabilization was conducted with 80% acetone and PCV1 detection was conducted at GSK laboratories with a secondary antibody linked to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Immunodetection of PCV1 viral protein was considered indicative of positive infection.

Detection of productive PCV1 in human cell lines

The infectivity assay was repeated in three human cell lines: MRC5 (a diploid cell line), U937 (a monocytic cell line), and Hep2 (a transformed cell line). The PK15 permissive cell line was included in these assays as a positive control. Detection of PCV1 mRNA expression by Q-PCR was considered indicative of the presence of infective viral particles.

Detection of PCV1 in archived clinical trial stool and serum samples

Blinded, retrospective laboratory evaluation was undertaken of archived samples from four completed clinical trials of Rotarix™ to assess for the presence of PCV1 DNA in stool samples and for evidence of serologic response to PCV1 following vaccination (NCT01511133). Table 4 provides an overview of the four selected Rotarix™ studies (NCT00169455, NCT00137930, NCT00757770, and NCT00263666).62–65 The studies were conducted in Asia, Europe, Latin America and Africa. In three of the studies, infants were required to be healthy at trial entry.62–64 The fourth study evaluated Rotarix™ administration in HIV-positive infants.65 This study was specifically included since it was speculated that if replication of PCV1 were to occur, it might be enhanced in immunocompromised infants. In all four trials, infants received their first dose of Rotarix™ between 6 to 12 weeks of age. Infants received two vaccine doses in all studies, with the exception of the study in HIV-positive infants in which a three dose vaccination schedule was used.

Table 4. Overview of Rotarix™ clinical studies included in the retrospective analysis for the presence of PCV1 DNA in stool samples and anti-PCV1 antibodies in serum samples.

| Study (No. subjects) |

Location | Population (Schedule) |

Post-vaccination sampling* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 162 [103477] (n = 30) |

Thailand | Healthy infants (2 doses) |

Stool: Day 7, 15 Serum: Post-dose 2 |

| Study 2 63 [104480] (n = 20) |

Finland | Healthy infants (2 doses) |

Stool: Day 7, 15 Serum: Post-dose 2 |

| Study 364 [444563/033] (n = 10) |

Peru | Healthy infants (2 doses) |

Stool: Day 3, 7, 10, 15, 30, 45 Serum: Post-dose 2 |

| Study 465 [444563/022] (n = 20) |

South Africa | HIV-positive infants (3 doses) |

Stool: Day 7, 15, 22 Serum: Post-dose 3 |

All stool samples collected post-dose 1. NCT study numbers: 103477, NCT00169455; 104480, NCT00137930; 444563/033, NCT00757770; 444563/022, NCT00263666

Stool samples were available for at least two time points post-dose 1 for evaluation of PCV1 DNA. Stool samples were not tested for the presence of PCV1 DNA post-dose 2. Serologic testing for anti-PCV1 antibodies was performed on samples collected prior to the first dose and after administration of the last vaccine dose. From each study, the first 10 vaccine recipients and the first 10 placebo recipients who completed the vaccination course and had samples of sufficient volume to allow testing (stool samples ≥100 μl and serum samples ≥250 μl) were included in this analysis. All laboratory assays were performed in a blinded manner (i.e., individuals responsible for testing were blinded to study group assignments).

Detection of PCV DNA in stool samples was performed by Q-PCR analysis. Two replicates were tested for each sample. For the test to be reported as positive or negative, the replicates had to provide concordant findings. If the results of the replicate testing were not concordant, a third replicate was tested to determine the final result for the sample. Final results for discordant samples were reported as positive if the third replicate was found positive and as inconclusive if the third replicate was negative or inconclusive. If PCV DNA was detected, DNA sequencing was performed to compare the identity of the amplified DNA to the PCV1 vaccine sequence.

Anti-PCV1 antibody response was assessed in pre-vaccination and post-vaccination serum samples at the Laboratory of Virology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, using an immuno-peroxidase monolayer assay (IPMA). This assay which has previously been used to detect anti-PCV1 in pig serum samples66 was adapted to test the human serum samples by replacing the anti-swine antibodies conjugated with peroxidase with an anti-human IgG conjugate. PCV1 IPMA-positive detection was characterized by (mainly) nuclear staining of PCV1-infected PK15 cells. An anti-PCV1 positive swine serum was used as positive control in the assay as no human positive serum was available.

Blinded, retrospective laboratory evaluation of archived serum samples from two clinical trials of GSK Biologicals’ IPV-containing vaccines was also undertaken to assess for evidence of serologic response to PCV1 following vaccination (NCT01651247). Both studies were phase III randomized controlled trials conducted at multiple centers in the United States.67,68 In the first study (217744/085), infants received three doses of a combination diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, recombinant hepatitis B and IPV vaccine (DTPA-HBV-IPV; Pediarix™) or separately administered DTPA, HBV, and IPV vaccines at 2, 4, and 6 mo of age.67 In the second study (NCT00148941), children aged 4–6 y received a single dose of either a combination DTPa-IPV vaccine (Kinrix™) or separately administered DTPa and IPV vaccines.68 Blood samples were collected prior to vaccination and one month after the last vaccine dose. Archived samples were tested for a subset of 40 subjects from a single study center for each study. Stool samples were not collected from subjects who received IPV-containing vaccines, since these vaccines were not administered orally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The results presented in this manuscript represent the combined efforts of a cross-functional team at GSK Vaccines. The authors would especially like to thank the following individuals: Emmanuel Hanon who was extensively involved in the manufacturing investigation; Michel Protz, Carine Letellier and Camille Planty from the laboratories involved in the design and conduct of infectivity assays; Cathy Hollaert who performed infectivity assays; Matthieu Bastin, Gregory Gimenne and Benedicte Brasseur for sample logistics; Valérie Wansard, Laurence Pesché and Nathalie Houard who performed the Q-PCR testing to assess the presence of PCV1 DNA in stool samples archived from completed clinical trials of Rotarix™; Thomas Hennekinne, Stéphanie Fannoy and Serge Durviaux who performed the sequencing of the PCV DNA in the samples where it was detected; Wayde Weston for providing critical input on the IPV study; and Elysia Tusavitz for providing US regulatory guidance and support for the investigation.

The authors would also like to acknowledge Jennifer Coward (freelance medical writer, United Kingdom, on behalf of GSK Vaccines) for providing medical writing assistance; Luise Kalbe (GSK Vaccines), Julia Donnelly (freelance publication manager, United Kingdom, on behalf of GSK Vaccines) and Manjula K (GSK Vaccines) for publication coordination.

Rotarix, Pediarix and Kinrix are trademarks of the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies.

RotaTeq is a trademark of Merck and Co., Inc.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BLA

biologics license application

- CBER

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research

- CCID50

median cell culture infective dose

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GSK

GlaxoSmithKline

- HRV

human rotavirus

- IPV

inactivated poliovirus

- NIBSC

National Institute for Biological Standards and Control

- PCV1

porcine circovirus type 1

- PCV2

porcine circovirus type 2

- PK15

porcine kidney cells

- Q-PCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- ST

swine testes cells

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

All authors are/were employed by the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies. All authors (except JPC and SP) also hold stock ownership/restricted shares from the sponsoring company. G Dubin also declares to have received royalties from Wyeth Pharmaceuticals in the past.

Funding

All studies described in this investigation were sponsored and funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, Rixensart, Belgium. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA was involved in all stages of the conduct of the investigation and analysis; and also met all costs associated with the development and publishing of the manuscript.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/vaccines/article/25973

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/vaccines/article/25973

References

- 1.Victoria JG, Wang C, Jones MS, Jaing C, McLoughlin K, Gardner S, Delwart EL. Viral nucleic acids in live-attenuated vaccines: detection of minority variants and an adventitious virus. J Virol. 2010;84:6033–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02690-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of the Federal Register. Code of Federal Regulations, 9 CFR and 21 CFR part 630 (Additional Standards for Viral Vaccines). 1996 and earlier versions. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2001-title9-vol1/pdf/CFR-2001-title9-vol1-sec113-47.pdf Accessed July 2013.

- 3.Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresee JS, Glass RI. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:304–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parashar UD, Burton A, Lanata C, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Steele D, Birmingham M, Glass RI. Global mortality associated with rotavirus disease among children in 2004. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(Suppl 1):S9–15. doi: 10.1086/605025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atherly DE, Lewis KD, Tate J, Parashar UD, Rheingans RD. Projected health and economic impact of rotavirus vaccination in GAVI-eligible countries: 2011-2030. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl 1):A7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation Meeting of the immunization Strategic Advisory Group of Experts, April 2009--conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:220–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pérez-Schael I, Velázquez FR, Abate H, Breuer T, Clemens SC, Cheuvart B, Espinoza F, Gillard P, Innis BL, et al. Human Rotavirus Vaccine Study Group Safety and efficacy of an attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:11–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Prymula R, Schuster V, Tejedor JC, Cohen R, et al. Efficacy of human rotavirus vaccine against rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first 2 years of life in European infants: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet 2007;370:1757-63; PMID:18037080; 10.1016/ S0140-6736(07)61744-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Linhares AC, Velazquez FR, Perez-Schael I, Saez-Llorens X, Abate H, Espinoza F, et al. Efficacy and safety of an oral live attenuated human rotavirus vaccine against rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first 2 years of life in Latin American infants: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. Lancet 2008;371:1181-89; PMID:18395579; 10.1016/ S0140-6736(08)60524-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Phua KB, Lim FS, Lau YL, Nelson EA, Huang LM, Quak SH, Lee BW, van Doorn LJ, Teoh YL, Tang H, et al. Rotavirus vaccine RIX4414 efficacy sustained during the third year of life: a randomized clinical trial in an Asian population. Vaccine. 2012;30:4552–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madhi SA, Cunliffe NA, Steele D, Witte D, Kirsten M, Louw C, Ngwira B, Victor JC, Gillard PH, Cheuvart BB, et al. Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:289–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawamura N, Tokoeda Y, Oshima M, Okahata H, Tsutsumi H, Van Doorn LJ, Muto H, Smolenov I, Suryakiran PV, Han HH. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of RIX4414 in Japanese infants during the first two years of life. Vaccine. 2011;29:6335–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tregnaghi MW, Abate HJ, Valencia A, Lopez P, Da Silveira TR, Rivera L, Rivera Medina DM, Saez-Llorens X, Gonzalez Ayala SE, De León T, et al. Rota-024 Study Group Human rotavirus vaccine is highly efficacious when coadministered with routine expanded program of immunization vaccines including oral poliovirus vaccine in Latin America. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:e103–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182138278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilliland SM, Forrest L, Carre H, Jenkins A, Berry N, Martin J, Minor P, Schepelmann S. Investigation of porcine circovirus contamination in human vaccines. Biologicals. 2012;40:270–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baylis SA, Finsterbusch T, Bannert N, Blümel J, Mankertz A. Analysis of porcine circovirus type 1 detected in Rotarix vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29:690–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClenahan SD, Krause PR, Uhlenhaut C. Molecular and infectivity studies of porcine circovirus in vaccines. Vaccine. 2011;29:4745–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma H, Shaheduzzaman S, Willliams DK, Gao Y, Khan AS. Investigations of porcine circovirus type 1 (PCV1) in vaccine-related and other cell lines. Vaccine. 2011;29:8429–37. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranucci CS, Tagmyer T, Duncan P. Adventitious Agent Risk Assessment Case Study: Evaluation of RotaTeq(R) for the Presence of Porcine Circovirus. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol. 2011;65:589–98. doi: 10.5731/pdajpst.2011.00827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suryakiran PV, Vinals C, Vanfraechem K, Han HH, Guerra Y, Buyse H. The human rotavirus vaccine RIX4414 in infants: An integrated clinical safety summary. Presented at Excellence in Paediatrics; Istanbul, Turkey, 30 November–3 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tischer I, Gelderblom H, Vettermann W, Koch MA. A very small porcine virus with circular single-stranded DNA. Nature. 1982;295:64–6. doi: 10.1038/295064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tischer I, Mields W, Wolff D, Vagt M, Griem W. Studies on epidemiology and pathogenicity of porcine circovirus. Arch Virol. 1986;91:271–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01314286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hattermann K, Maerz A, Slanina H, Schmitt C, Mankertz A. Assessing the risk potential of porcine circoviruses for xenotransplantation: consensus primer-PCR-based search for a human circovirus. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:547–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2004.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellis JA, Wiseman BM, Allan G, Konoby C, Krakowka S, Meehan BM, McNeilly F. Analysis of seroconversion to porcine circovirus 2 among veterinarians from the United States and Canada. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;217:1645–6. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.217.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dulac GC, Afshar A. Porcine circovirus antigens in PK-15 cell line (ATCC CCL-33) and evidence of antibodies to circovirus in Canadian pigs. Can J Vet Res. 1989;53:431–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tischer I, Bode L, Peters D, Pociuli S, Germann B. Distribution of antibodies to porcine circovirus in swine populations of different breeding farms. Arch Virol. 1995;140:737–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01309961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raye W, Muhling J, Warfe L, Buddle JR, Palmer C, Wilcox GE. The detection of porcine circovirus in the Australian pig herd. Aust Vet J. 2005;83:300–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2005.tb12747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Kapoor A, Slikas B, Bamidele OS, Wang C, Shaukat S, Masroor MA, Wilson ML, Ndjango JB, Peeters M, et al. Multiple diverse circoviruses infect farm animals and are commonly found in human and chimpanzee feces. J Virol. 2010;84:1674–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02109-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hattermann K, Roedner C, Schmitt C, Finsterbusch T, Steinfeldt T, Mankertz A. Infection studies on human cell lines with porcine circovirus type 1 and porcine circovirus type 2. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:284–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2004.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krakowka S, Ellis JA, Meehan B, Kennedy S, McNeilly F, Allan G. Viral wasting syndrome of swine: experimental reproduction of postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in gnotobiotic swine by coinfection with porcine circovirus 2 and porcine parvovirus. Vet Pathol. 2000;37:254–63. doi: 10.1354/vp.37-3-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Opriessnig T, Halbur PG. Concurrent infections are important for expression of porcine circovirus associated disease. Virus Res. 2012;164:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segalés J. Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) infections: clinical signs, pathology and laboratory diagnosis. Virus Res. 2012;164:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delwart E, Li L. Rapidly expanding genetic diversity and host range of the Circoviridae viral family and other Rep encoding small circular ssDNA genomes. Virus Res. 2012;164:114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurgel RG, Bohland AK, Vieira SC, Oliveira DM, Fontes PB, Barros VF, Ramos MF, Dove W, Nakagomi T, Nakagomi O, et al. Incidence of rotavirus and all-cause diarrhea in northeast Brazil following the introduction of a national vaccination program. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1970–5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Correia JB, Patel MM, Nakagomi O, Montenegro FM, Germano EM, Correia NB, Cuevas LE, Parashar UD, Cunliffe NA, Nakagomi T. Effectiveness of monovalent rotavirus vaccine (Rotarix) against severe diarrhea caused by serotypically unrelated G2P[4] strains in Brazil. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:363–9. doi: 10.1086/649843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Palma O, Cruz L, Ramos H, de Baires A, Villatoro N, Pastor D, de Oliveira LH, Kerin T, Bowen M, Gentsch J, et al. Effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination against childhood diarrhoea in El Salvador: case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2825. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanzieri TM, Costa I, Shafi FA, Cunha MH, Ortega-Barria E, Linhares AC, Colindres RE. Trends in hospitalizations from all-cause gastroenteritis in children younger than 5 years of age in Brazil before and after human rotavirus vaccine introduction, 1998-2007. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:673–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181da8f23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson V, Hernandez-Pichardo J, Quintanar-Solares M, Esparza-Aguilar M, Johnson B, Gomez-Altamirano CM, Parashar U, Patel M. Effect of rotavirus vaccination on death from childhood diarrhea in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:299–305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sáfadi MA, Berezin EN, Munford V, Almeida FJ, de Moraes JC, Pinheiro CF, Racz ML. Hospital-based surveillance to evaluate the impact of rotavirus vaccination in São Paulo, Brazil. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:1019–22. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e7886a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.do Carmo GM, Yen C, Cortes J, Siqueira AA, de Oliveira WK, Cortez-Escalante JJ, Lopman B, Flannery B, de Oliveira LH, Carmo EH, et al. Decline in diarrhea mortality and admissions after routine childhood rotavirus immunization in Brazil: a time-series analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gurgel RQ, Ilozue C, Correia JB, Centenari C, Oliveira SM, Cuevas LE. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on diarrhoea mortality and hospital admissions in Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:1180–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Justino MC, Linhares AC, Lanzieri TM, Miranda Y, Mascarenhas JD, Abreu E, Guerra SF, Oliveira AS, da Silva VB, Sanchez N, et al. Effectiveness of the monovalent G1P[8] human rotavirus vaccine against hospitalization for severe G2P[4] rotavirus gastroenteritis in Belém, Brazil. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:396–401. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182055cc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanzieri TM, Linhares AC, Costa I, Kolhe DA, Cunha MH, Ortega-Barria E, et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on childhood deaths from diarrhea in Brazil. Int J Infect Dis 2011;15:e206-10; PMID:21193339; 10.1016/ j.ijid.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Macartney KK, Porwal M, Dalton D, Cripps T, Maldigri T, Isaacs D, Kesson A. Decline in rotavirus hospitalisations following introduction of Australia’s national rotavirus immunisation programme. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:266–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molto Y, Cortes JE, De Oliveira LH, Mike A, Solis I, Suman O, Coronado L, Patel MM, Parashar UD, Cortese MM. Reduction of diarrhea-associated hospitalizations among children aged < 5 Years in Panama following the introduction of rotavirus vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(Suppl):S16–20. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefc68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quintanar-Solares M, Yen C, Richardson V, Esparza-Aguilar M, Parashar UD, Patel MM. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on diarrhea-related hospitalizations among children < 5 years of age in Mexico. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(Suppl):S11–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefb32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raes M, Strens D, Vergison A, Verghote M, Standaert B. Reduction in pediatric rotavirus-related hospitalizations after universal rotavirus vaccination in Belgium. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:e120–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318214b811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richardson V, Parashar U, Patel M. Childhood diarrhea deaths after rotavirus vaccination in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:772–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1100062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snelling TL, Andrews RM, Kirkwood CD, Culvenor S, Carapetis JR. Case-control evaluation of the effectiveness of the G1P[8] human rotavirus vaccine during an outbreak of rotavirus G2P[4] infection in central Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:191–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yen C, Armero Guardado JA, Alberto P, Rodriguez Araujo DS, Mena C, Cuellar E, Nolasco JB, De Oliveira LH, Pastor D, Tate JE, et al. Decline in rotavirus hospitalizations and health care visits for childhood diarrhea following rotavirus vaccination in El Salvador. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(Suppl):S6–10. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefa05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bayard V, DeAntonio R, Contreras R, Tinajero O, Castrejon MM, Ortega-Barría E, Colindres RE. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on childhood gastroenteritis-related mortality and hospital discharges in Panama. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e94–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braeckman T, Van Herck K, Meyer N, Pirçon JY, Soriano-Gabarró M, Heylen E, Zeller M, Azou M, Capiau H, De Koster J, et al. RotaBel Study Group Effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination in prevention of hospital admissions for rotavirus gastroenteritis among young children in Belgium: case-control study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4752. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cortese M, Immergluck LC, Held M, Jain S, Chan T, Grizas A, et al. Effectiveness of monovalent rotavirus vaccine among children in two US states. Presented at 10th International Rotavirus Symposium; Bangkok, Thailand, 19–21 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuehn BM. FDA: Benefits of rotavirus vaccination outweigh potential contamination risk. JAMA. 2010;304:30–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.World Health Organization. Statement of the Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety on Rotarix. 26 March 2010. Available at: http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/committee/topics/rotavirus/rotarix_statement_march_2010/en/ Accessed July 2013.

- 55.European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency confirms positive benefit-risk balance of Rotarix. 22 July 2010. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2010/07/WC500094972.pdf Accessed July 2013.

- 56.Tsang SX, Switzer WM, Shanmugam V, Johnson JA, Goldsmith C, Wright A, Fadly A, Thea D, Jaffe H, Folks TM, et al. Evidence of avian leukosis virus subgroup E and endogenous avian virus in measles and mumps vaccines derived from chicken cells: investigation of transmission to vaccine recipients. J Virol. 1999;73:5843–51. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5843-5851.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hussain AI, Shanmugam V, Switzer WM, Tsang SX, Fadly A, Thea D, Helfand R, Bellini WJ, Folks TM, Heneine W. Lack of evidence of endogenous avian leukosis virus and endogenous avian retrovirus transmission to measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine recipients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:66–72. doi: 10.3201/eid0701.010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allan GM, McNeilly F, Foster JC, Adair BM. Infection of leucocyte cell cultures derived from different species with pig circovirus. Vet Microbiol. 1994;41:267–79. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Welch J, Bienek C, Gomperts E, Simmonds P. Resistance of porcine circovirus and chicken anemia virus to virus inactivation procedures used for blood products. Transfusion. 2006;46:1951–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Dea MA, Hughes AP, Davies LJ, Muhling J, Buddle R, Wilcox GE. Thermal stability of porcine circovirus type 2 in cell culture. J Virol Methods. 2008;147:61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mankertz A, Hillenbrand B. Replication of porcine circovirus type 1 requires two proteins encoded by the viral rep gene. Virology. 2001;279:429–38. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kerdpanich A, Chokephaibulkit K, Watanaveeradej V, Vanprapar N, Simasathien S, Phavichitr N, Bock HL, Damaso S, Hutagalung Y, Han HH. Immunogenicity of a live-attenuated human rotavirus RIX4414 vaccine with or without buffering agent. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6:254–62. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.3.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Bouckenooghe A, Suryakiran PV, Smolenov I, Han HH. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity and safety of the human rotavirus vaccine RIX4414 oral suspension (liquid formulation) in Finnish infants. Vaccine. 2011;29:2079–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.López P, Galan Herrera JF, Cervantes Y, Costa Clemens SA, Aguirre F, Yarzabal JP, et al. Three consecutive production lots of the human monovalent RIX4414 G1P[8] rotavirus vaccine, Rotarix, induce a consistent immune response in Latin American infants. Presented at the 4th World Congress of the World Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases; Warsaw, Poland, 1–4 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steele AD, Madhi SA, Louw CE, Bos P, Tumbo JM, Werner CM, Bicer C, De Vos B, Delem A, Han HH. Safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of human rotavirus vaccine RIX4414 in human immunodeficiency virus-positive infants in South Africa. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:125–30. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f42db9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Labarque GG, Nauwynck HJ, Mesu AP, Pensaert MB. Seroprevalence of porcine circovirus types 1 and 2 in the Belgian pig population. Vet Q. 2000;22:234–6. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2000.9695065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pichichero ME, Bernstein H, Blatter MM, Schuerman L, Cheuvart B, Holmes SJ, 085 Study Investigators Immunogenicity and safety of a combination diphtheria, tetanus toxoid, acellular pertussis, hepatitis B, and inactivated poliovirus vaccine coadministered with a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and a Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. J Pediatr. 2007;151:43–9, e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Black S, Friedland LR, Ensor K, Weston WM, Howe B, Klein NP. Diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis and inactivated poliovirus vaccines given separately or combined for booster dosing at 4-6 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:341–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181616180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rotarix™ BLA clinical review. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/ucm133580.pdf Accessed July 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.