Abstract

Background

Despite widespread use in HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, the effectiveness of tenofovir (TDF) has not been studied extensively outside of small HBV-HIV coinfected cohorts. We examined the effect of prior lamivudine treatment (3TC) and other factors on HBV DNA suppression with TDF in a multi-site clinical cohort of coinfected patients.

Methods

We studied all patients enrolled in the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems cohort from 1996-2011 who had chronic HBV and HIV infection, initiated a TDF-based regimen continued for ≥3 months and had on-treatment HBV measurements. We used Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox-Proportional hazards to estimate time to suppression (HBV DNA level <200 IU/ml or <1000 copies/ml) by selected covariates.

Results

Among 397 coinfected patients on TDF, 91% were also on emtricitabine or 3TC concurrently, 92% of those tested were HBeAg-positive, 196 (49%) had prior 3TC exposure; 192 (48%) achieved HBV DNA suppression over a median of 28 months (IQR 13-71). Median time to HBV DNA suppression was 17 months for those who were 3TC-naïve and 50 months for those who were 3TC-exposed. After controlling for other factors, prior 3TC exposure, baseline HBV DNA level >10,000 IU/ml, and lower nadir CD4 count were independently associated with decreased likelihood of HBV DNA suppression on TDF.

Conclusion

These results emphasize the role of prior 3TC exposure and immune response on delayed HBV suppression on TDF.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, tenofovir, lamivudine, HIV

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in HIV-infected individuals is estimated to be up to ten-fold higher than the general population in developed countries 1. Patients coinfected with HBV and HIV often have higher HBV DNA levels and more rapid progression to cirrhosis or hepatic decompensation than patients with HBV alone 2,3. Coinfected individuals are also at greater risk of liver-related mortality compared to their HBV or HIV monoinfected counterparts 4. Because effective cures for chronic HBV infection are limited and spontaneous anti-HBs seroconversion occurs infrequently, sustained HBV viral suppression remains the primary goal of current HBV treatment, particularly since higher baseline HBV viral levels are associated with a higher incidence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma 5,6.

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) was first licensed for the treatment of HIV in 2001 and is one of the most commonly prescribed nucleos(t)ide analogues in combination antiretroviral therapy (ART). The efficacy of TDF as a potent antiviral agent against HBV was first described in HBV-HIV coinfected patients, although much of these data comprised small studies with short-term follow-up or retrospective analyses of coinfected subsets of patients in treatment trials 7-10. Given the current paucity of alternative HBV therapies, it is important to evaluate how TDF performs in real-world settings over long-term follow-up, particularly in heterogeneous patient populations.

Outside clinical trial settings, many HBV-HIV coinfected patients have been exposed to lamivudine (3TC), an antiviral agent active against HIV and HBV. However, 3TC has a low genetic barrier for HBV resistance, leading to rapid development of HBV resistance when 3TC is used alone 11. In vitro data suggest 3TC resistance may impact the effectiveness of TDF against HBV but the full significance of this finding in clinical practice settings remains unknown 12,13. We studied a large cohort of HIV-infected individuals with chronic HBV infection in routine care at eight clinical sites across the United States to examine the effect of prior treatment with 3TC and other risk factors on HBV DNA suppression among patients treated with TDF.

METHODS

Study Population

The Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR) Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) cohort includes over 27,000 HIV-infected adults in clinical care from 1995 to the present 14. Institutional review boards at each site approved the study protocol.

We identified all patients enrolled in CNICS between January 1996 to September 2011 who were coinfected with HBV, defined by the presence of a reactive HBV surface antigen or positive plasma HBV DNA level, and studied those coinfected patients with detectable HBV DNA or reactive e antigen who initiated ART with a regimen containing TDF and had at least one HBV DNA measurement during treatment.

Data Sources & Study Definitions

The CNICS data repository captures comprehensive clinical data that include standardized diagnosis, medication, laboratory, and demographic information collected through Electronic Health Records (EHR) and other institutional data systems at each site 14. Data quality assessment is conducted at the sites prior to data transmission and at the time of submission to the CNICS Data Management Core (DMC). After integration into the repository, data undergo extensive quality assurance procedures and data quality issues are reported to CNICS sites by the DMC to investigate and correct. Data from each site are updated, fully reviewed, and integrated into the repository quarterly 14 (http://www.uab.edu/cnics).

We examined the association between HBV suppression, demographic and clinical factors including baseline HBV viral load and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) defined as those closest and prior to TDF initiation. Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) status was defined as ever having tested positive. The FIB-4 index was calculated as: age (years) x serum aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) / platelets (109/L) × (ALT [U/L]1/2). A FIB-4 score >3.25 has an estimated positive predictive value for advanced fibrosis (Ishak fibrosis score 4-6) of 65% 15. A positive HCV-antibody or HCV RNA level defined HCV infection. HBV DNA suppression was defined as the first HBV DNA value less than or equal to 200 IU/ml (or 1000 copies/ml) after TDF initiation, a threshold chosen to accommodate the different assays across sites.

Statistical Analysis

We examined whether time to HBV suppression after initiating TDF treatment differed among persons who were previously exposed to 3TC compared to those who were 3TC-naïve. Patients were observed from the date TDF treatment was initiated to the date of HBV suppression, the end of initial treatment, last HBV measurement or death, whichever occurred first.

We used log-rank tests to examine the association between HBV suppression and age, HIV transmission risk factor, sex, race/ethnicity, nadir or baseline CD4 count (categorized as <200, 200-350, 351-500, and >500 cells per cubic millimeter), baseline serum ALT >80 U/L (twice 40 U/L, the upper range of normal), baseline HIV RNA (categorized as <10,000, 10,000-99,999, ≥100,000 copies/ml), HBeAg status, HCV infection status, baseline HBV DNA level >10,000 IU/ml 16 and calendar year of TDF initiation. The association between the aforementioned variables and the main predictor, prior 3TC exposure, was assessed using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum and t-tests for continuous variables. Covariates associated with the outcome from bivariate analysis at the p<0.05 level were evaluated for collinearity using Chi-squared and Spearman correlation coefficients. Variables relevant to HBV suppression were included in the final model.

Kaplan-Meier estimates and Cox proportional hazards were used to describe time to HBV DNA suppression and the effect of prior 3TC exposure, adjusting for age, nadir CD4 count, HBV DNA level, race, ALT, and year of TDF initiation to control for secular trends in HIV care over calendar time. Tests of proportional hazards were conducted to confirm assumptions and ensure interpretability. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC) and Stata version 11 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patients

Among 24,911 patients enrolled in the CNICS cohort between January 1996 and September 2011, 1,067 (4.3%) patients had chronic HBV infection. Of the 1,067 HBV coinfected patients, 939 were treated with TDF for at least 3 months; 463 of these had HBV DNA measurements on treatment, of which 66 were excluded because the baseline HBV DNA was undetectable; for a final study cohort of 397 patients. Baseline characteristics of patients missing HBV measurements were similar to those with HBV measurements aside from a lower proportion with baseline ALT >80 U/L (17% vs 25%). As shown in Table 1, the median age of the study cohort at the time of TDF initiation was 40 years, 51% of the participants were white, 90% were men, 14% reported injection drug use as a risk factor for HIV transmission and 18% of patients also had HCV infection. Nearly all (91%) of these patients were also on concurrent 3TC or emtricitabine (FTC). The median nadir CD4 count was 128 cells/mm3 and baseline HIV RNA was 16,865 copies/ml. The majority of evaluable patients had baseline HBV DNA levels ≥10,000 IU/ml (79%) and/or positive HBeAg status (92%). Forty-six (12%) patients had a baseline FIB-4 score >3.25 suggestive of advanced fibrosis.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the HBV-HIV Coinfected Study Population

| Total (n=397) | Prior 3TC (n=196) | No Prior 3TC (n=201) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 40 (35-46) | 40 (36-46) | 40 (33-46) | 0.20 |

| Sex, male | 357 (90) | 176 (90) | 181 (90) | 0.93 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 204 (51) | 104 (53) | 100 (50) | |

| Black | 170 (43) | 87 (44) | 83 (41) | |

| Other | 23 (6) | 5 (3) | 18 (9) | 0.02 |

| HCV coinfection | 71 (18) | 41 (21) | 30 (15) | 0.12 |

| HIV Risk factor | ||||

| MSM | 250 (63) | 123 (63) | 127 (63) | |

| IDU | 55 (14) | 29 (15) | 25 (12) | |

| Heterosexual | 73 (18) | 31 (16) | 42 (21) | |

| Other | 20 (5) | 13 (6) | 7 (4) | 0.29 |

| AIDS-defining condition | 149 (50) | 82 (59) | 67 (42) | < 0.01 |

| Baseline CD4, cells/mm3 (median, IQR) | 229 (89-392) | 243 (102-393) | 214 (75-391) | 0.49 |

| Nadir CD4, cells/mm3 (median, IQR) | 128 (25-290) | 68 (14-209) | 179 (46-353) | <0.01 |

| Baseline HIV RNA, copies/ml | ||||

| <10,000 | 178 (46) | 120 (63) | 58 (30) | |

| 10,000-100,000 | 119 (31) | 40 (21) | 79 (40) | |

| >100,000 | 89 (23) | 31 (16) | 58 (30) | < 0.01 |

| HBeAg-positive* | 294 (92) | 166 (95) | 126 (89) | 0.12 |

| Baseline HBV DNA, lU/ml | ||||

| <10,000 | 46 (21) | 15 (17) | 31 (23) | 0.55 |

| 10,000-100,000 | 27 (12) | 11 (13) | 16 (12) | |

| >100,000 | 149 (67) | 62 (70) | 87 (65) | |

| Baseline ALT, U/L (median, IQR) | 51 (32-83) | 52 (32-75) | 50 (34-98) | 0.15 |

| Baseline FIB-4 score >3.25 | 46 (12) | 27 (14) | 19 (9) | 0.17 |

| Concurrent FTC/3TC use | 360 (91) | 167 (85) | 193 (96) | <0.01 |

| Time on study^, months (median, IQR) | 15 (7-30) | 19 (9-38) | 12 (6-20) | <0.01 |

Data are presented here as number (%) of patients for categorical variables unless otherwise noted.

3TC, lamivudine; IQR, interquartile range; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MSM, men who have sex with men; IDU, injection drug use; HBeAg, hepatitis B e-antigen; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; FTC, emtricitabine.

Among n=317 tested for HBeAg status.

Time on TDF until suppression or censoring.

Prior Lamivudine (3TC)

Of the 397 patients studied, 196 (49%) had a history of 3TC exposure before the initiation of TDF with a median duration on 3TC of 40 months (interquartile range (IQR), 16 to 74). 3TC-exposed patients had lower baseline HIV RNA values prior to the initiation of TDF likely due to HIV treatment experience. FIB-4 scores were comparable across groups. A higher proportion of patients with prior 3TC exposure were in care earlier in the HIV epidemic. Consistent with this difference, 3TC-experienced patients tended to initiate TDF earlier in calendar time than their naïve counterparts and had lower nadir CD4 counts than 3TC-naïve patients with median nadir CD4 count of 68 cells/mm3 compared with 179 cells/mm3, respectively.

HBV DNA Suppression on TDF

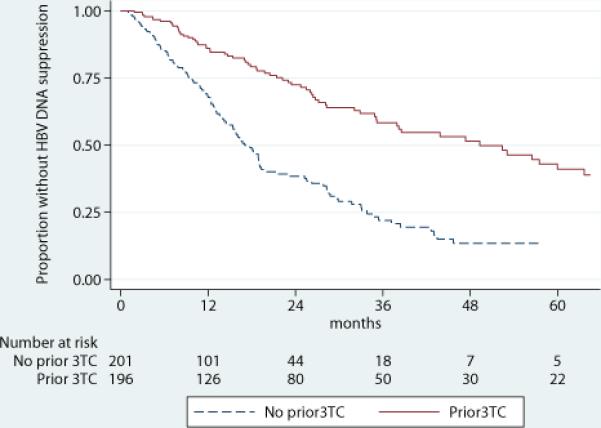

We observed HBV DNA suppression to <200 IU/ml in 192 (48% of 397) patients. The median time to suppression for the entire cohort was 28 months (IQR 13-71). Median time to HBV DNA suppression was 17 months for those who were 3TC-naïve and 50 months for those who were 3TC-exposed (Figure 1). As shown in Table 2, after adjusting for age, nadir CD4, baseline HBV level, ALT, race and year of TDF initiation, 3TC-exposed patients were significantly less likely to achieve suppression of HBV DNA during treatment with TDF, with an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 0.60 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.42, 0.85); p=0.004. In addition to prior 3TC exposure, a lower nadir CD4 count and higher baseline HBV viral burden (HBV DNA >10,000 IU/ml) were independent predictors of delayed HBV DNA suppression. Compared with patients whose nadir CD4 count were ≥500 cells/mm3, patients with nadir CD4 <200 cells/mm3 were almost half as likely to suppress HBV DNA while on TDF (aHR: 0.53 (95% CI 0.31, 0.88); p=0.02). The median time to HBV suppression for patients whose nadir CD4 count was <200 cells/mm3 was 29 months compared to 9 months for those whose CD4 nadir was ≥500 cells/mm3. Patients with baseline HBV DNA levels >10,000 IU/ml were also less likely to suppress (aHR: 0.34 (95% CI: 0.22, 0.53); p<0.001), with a median time to HBV suppression of 30 months compared to 9 months for those with lower HBV DNA levels.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of HBV DNA Suppression by Prior Lamivudine (3TC)

Table 2.

Association of Lamividine Exposure and Other Factors with HBV Suppression during Treatment with Tenofovir in Bivariate and Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Analyses

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3TC exposure | 0.38 (0.28, 0.52) | <0.01 | 0.60 (0.42, 0.85) | <0.01 |

| Age >40 years | 1.31 (0.98, 1.75) | 0.07 | 1.08 (0.81, 1.43) | 0.62 |

| Nadir CD4, cells/mm3 (Ref: ≥500) | ||||

| 350-499 | 0.27 (0.17, 0.45) | <0.01 | 0.58 (0.33, 1.01) | 0.06 |

| 200-349 | 0.26 (0.16, 0.42) | <0.01 | 0.55 (0.32, 0.93) | 0.03 |

| <200 | 0.21 (0.14, 0.31) | <0.01 | 0.53 (0.31, 0.88) | 0.02 |

| HBV DNA level >10,000 lU/ml | 0.25 (0.15, 0.40) | <0.01 | 0.34 (0.22, 0.53) | <0.01 |

| Race (Ref: White) | ||||

| Black | 0.72 (0.54, 0.97) | 0.03 | 0.78 (0.56, 1.08) | 0.14 |

| Other | 1.30 (0.63, 2.63) | 0.48 | 1.21 (0.60, 2.45) | 0.61 |

| Serum ALT >80 U/L | 1.43 (1.05, 1.94) | 0.02 | 1.56 (1.14, 2.15) | 0.01 |

| Calendar year of TDF start | 1.3 (1.23, 1.39) | <0.01 | 1.22 (1.14, 1.31) | <0.01 |

CI, confidence interval; 3TC, lamivudine; Ref, reference category; HBV, hepatitis B; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TDF, tenofovir.

Later calendar year of TDF initiation and baseline ALT >80 U/L were also associated with increased likelihood of HBV DNA suppression. A history of an AIDS-defining condition was associated with HBV suppression and prior 3TC in unadjusted analyses, but was not significant in the multivariable model while nadir CD4 remained an independent predictor; prior AIDS-defining condition was therefore not included in the final model. We found no significant difference in HBV suppression between patients who were on TDF alone versus combination therapy with TDF and 3TC or FTC. However, our ability to detect this difference may have been limited as only 37 (9%) patients were on TDF alone for their HBV infection at the start of therapy.

Of the 192 patients who achieved HBV suppression, 111 had at least two subsequent HBV measures that enabled us to examine viral breakthrough. Seven of these patients had a recurrent detectable HBV DNA on TDF (all but one with HBV DNA level ≥10,000 IU/ml), between 12 and 87 months after TDF initiation. All but two had concurrent HIV suppression at the time of breakthrough.

Among the 127 patients with positive HBeAg who had HBeAg retested on therapy, 30 (24%) had subsequent HBeAg loss, with no difference between groups defined by prior 3TC or HBV suppression. A greater proportion of patients who suppressed their HBV DNA had serum ALT <40 U/L at the end of follow-up than those who did not (68% versus 51%, p=0.001). Those who suppressed were also less likely to have subsequent FIB-4 scores >3.25 (7% versus 20%, p<0.001).

Sensitivity Analyses

Patients included in the analysis had a median of two (interquartile range, IQR 1-3) serum HBV DNA measurements over a median of 15 months (IQR 7-30) while under observation. While there was no difference in number of HBV measurements per patient across 3TC exposure groups, the 3TC-naive group was assessed slightly more frequently. Median time from start of TDF to first HBV measurement was 4 months for 3TC-naïve and 6.4 months for 3TC-exposed patients (p=0.02). Median time between HBV follow-up measurements was 4.8 months for 3TC-naïve and 7 months for 3TC-exposed patients (p<0.01). To address whether or not this differential frequency could account for the observed difference in median time until HBV suppression, we examined the proportion of 3TC-exposed and 3TC-naïve patients who had HBV measurements before and after the median time to suppression among 3TC-naïve patients (17 months). We found that 27% of 3TC-exposed and 32% of 3TC-naïve patients had an HBV measurement within 8 to 16 months (p=0.25) following TDF initiation, 21% of 3TC-exposed and 22% of 3TC-naïve patients (p=0.81) had an HBV measurement between 16 to 24 months. Thus, the 3TC-exposed and 3TC-naïve groups were equally likely to be observed in the early follow-up period that included the median time to suppression among 3TC-naïve patients.

To address the possibility that adherence to medications could have accounted for the difference in time to HBV suppression, we conducted survival analysis on the subset of 250 patients who achieved HIV RNA suppression to <50 copies/ml by six months as a proxy for adherence. Our results were robust in this subset of patients with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.62 for HBV suppression with prior 3TC exposure (95% CI 0.40, 0.95, p=0.03). Notably, the proportion of patients who achieved HIV RNA <50 copies/mL by six months was comparable between groups defined by prior 3TC (50% among 3TC-naïve versus 48% among 3TC-exposed, p=0.80).

DISCUSSION

We studied the long-term effectiveness of TDF combined with 3TC or FTC in the treatment of HBV in a large cohort of HBV-HIV coinfected patients in routine clinical care. Ours is the largest observational study to date of HIV-HBV coinfected patients on TDF. Among the 397 patients in our cohort who had HBV DNA assessed on TDF therapy, most of whom were HBeAg-positive, 48% achieved HBV suppression on TDF during a median of two years – comparable to rates of suppression reported in longitudinal studies of HBeAg-positive coinfected patients 7,17-19 and treatment-experienced HBV monoinfected patients 20 but lower than other prospective reports of coinfected patients 21, possibly due to the higher prevalence of positive HBeAg and/or lower nadir CD4 in our cohort. HBV suppression was durable among the subset of patients who continued to have HBV DNA measured and HBV viral breakthrough was infrequent, consistent with other long-term studies of coinfected patients17,22. Failure to achieve HBV DNA <200 IU/ml on TDF was independently associated with a higher baseline HBV DNA level – a well-established finding in both HBV monoinfected and coinfected patients 23,24. Notably, we found that lower nadir CD4 count and a history of prior 3TC exposure are independent risk factors for lack of HBV suppression on TDF.

Almost half of our cohort had prior 3TC exposure with a median duration of past therapy of over three years. Prolonged 3TC monotherapy for HBV can result in the accumulation of HBV mutations conferring resistance to 3TC in >90% coinfected patients after 4 years of therapy 11,25. Although TDF has been shown to perform well in 3TC-resistant HBV monoinfected 26,27 and coinfected 7 patients, we found that prior 3TC therapy was significantly associated with decreased likelihood of HBV DNA suppression with TDF, even after adjusting for potential confounding factors including CD4 count and baseline HBV viral level. Although 3TC and TDF do not appear to share the same pathway for drug resistance, cumulative mutations against 3TC may partially compromise TDF activity, as noted in in vitro studies 12,13. Inadequate inhibition of HBV viral replication during treatment with 3TC can also generate compensatory mutations and favor the selection of viral quasispecies with better fitness 28,29. This genetic heterogeneity has been linked with delayed response to TDF in coinfected patients 13.

Previous studies have reported a blunted HBV virologic response to TDF among 3TC-experienced compared with 3TC-naïve, in both HIV-HBV coinfected patients 21,30 and HBV-monoinfected patients 20. In a Spanish cohort of HIV-HBV coinfected patients, the mean time to HBV suppression was approximately twice as long in 3TC-experienced compared to 3TC-naïve patients 30. Other studies not reporting a difference were smaller and had higher proportions of 3TC-experienced patients 7,9,31 that limited their ability to detect such differences due to lack of heterogeneity.

We found nadir CD4 count to be an independent predictor of HBV suppression on TDF – with greater likelihood of HBV suppression the higher the nadir CD4 count. Prior reports have noted an association of lower nadir CD4 counts with HBV viremia on 3TC 11 and a trend toward delayed response to TDF 18. Baseline CD4 count has also been shown to influence HBV DNA decline among HIV-HBV coinfected patients on TDF 22 and adefovir 32. Patients with greater CD4 count gains on ART appear to be more likely to suppress HBV DNA on antiviral therapy 33. Immune status and restoration have also been shown to predict the kinetics of HBeAg clearance 34 and probability of HBsAg clearance on antiviral therapy 35, both important serologic benchmarks of HBV treatment success. These results, including our own, emphasize the key role of the host immune response in antiviral efficacy and clearance of HBV-infected hepatocytes 36. Our findings also complement longitudinal studies that demonstrate greater liver-related mortality among HBV-HIV coinfected patients with lower nadir CD4 in the ART era 4,37 and suggest that uncontrolled HBV viremia in patients with more advanced HIV-mediated immunosuppression may contribute to accelerated liver disease progression.

This study has several limitations. As with any observational study, our findings may have been influenced by unmeasured factors. Information about 3TC resistance in those who were 3TC-exposed was not available, and we were not able to assess the relationship between HBV suppression on TDF and outcomes of liver disease severity or cause-specific mortality. Data on outcomes of HBeAg or HBsAg seroconversion were also limited, and antibody to hepatitis delta (HDV) data not available. Although we could not examine adherence to medications directly, the significant difference in HBV DNA suppression observed between groups defined by prior 3TC was robust in the subset of patients who achieved HIV suppression in 6 months, suggesting that differential adherence did not account for our findings. HBV DNA was also measured infrequently and inconsistently in this cohort, reflecting clinical practice patterns 38. However, patients with baseline and follow-up HBV measurements had similar baseline characteristics to those with missing values. The median time from the start of TDF to first HBV measurement and median time between subsequent follow-up measurements differed by only a few months between 3TC-naïve and 3TC-exposed patients. In addition, the majority of patients were assessed by 17 months, which was the median time to suppression among 3TC-naïve patients. Our finding that the 3TC-exposed and 3TC-naïve group were equally likely to be observed in the early follow-up period between 8 to 24 months suggests that the observed difference in median time until HBV suppression was not due to differential frequency in HBV measurements. In addition, results of logistical analysis that evaluated HBV DNA suppression by specific time points were similar, suggesting that the timing of HBV testing did not influence our results.

In conclusion, we found that both low nadir CD4 count and prior 3TC treatment were significantly associated with decreased likelihood of HBV DNA suppression among patients treated with TDF after controlling for other factors. These results highlight the role of the host immune response as well as prior antiviral exposure in long-term HBV treatment effectiveness, and provide further support for initiation of ART at higher CD4 counts well before significant immune compromise has occurred. Future research is needed regarding interventions to increase the rate of HBV suppression in HBV-HIV coinfected patients and the potential link between lack of HBV DNA suppression on therapy and clinical HBV events.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This project was supported by the CFAR Network of Integrated Clinical Systems CNICS (5R24AI067039) funding from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. This research was also made possible by NIH-funded programs for the Centers for AIDS Research (P30 AI027757, P30 AI027763).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. JJE is a consultant to Gilead and Glaxo-Smith Klein. ETO is a consultant for Gilead and receives research funding from Gilead. MM has been a consultant for Gilead and Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) and has received research funding from BMS. Remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

This work was presented in part at the 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2013 in Atlanta, GA, 4 March 2013 (abstract 667).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44(1 Suppl):S6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benhamou Y. Hepatitis B in the HIV-coinfected patient. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Jul 1;45(Suppl 2):S57–65. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318068d1dd. discussion S66-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puoti M, Torti C, Bruno R, Filice G, Carosi G. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B in co-infected patients. J Hepatol. 2006;44(1 Suppl):S65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thio CL, Seaberg EC, Skolasky R, Jr., et al. HIV-1, hepatitis B virus, and risk of liver-related mortality in the Multicenter Cohort Study (MACS). Lancet. 2002 Dec 14;360(9349):1921–1926. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006 Jan 4;295(1):65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Jen CL, et al. Risk and predictors of mortality associated with chronic hepatitis B infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Aug;5(8):921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benhamou Y, Fleury H, Trimoulet P, et al. Anti-hepatitis B virus efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in HIV-infected patients. Hepatology. 2006 Mar;43(3):548–555. doi: 10.1002/hep.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dore GJ, Cooper DA, Pozniak AL, et al. Efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in antiretroviral therapy-naive and -experienced patients coinfected with HIV-1 and hepatitis B virus. J Infect Dis. 2004 Apr 1;189(7):1185–1192. doi: 10.1086/380398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacombe K, Gozlan J, Boelle PY, et al. Long-term hepatitis B virus dynamics in HIV-hepatitis B virus-co-infected patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. AIDS. 2005 Jun 10;19(9):907–915. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171404.07995.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ristig MB, Crippin J, Aberg JA, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate therapy for chronic hepatitis B in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis B virus-coinfected individuals for whom interferon-alpha and lamivudine therapy have failed. J Infect Dis. 2002 Dec 15;186(12):1844–1847. doi: 10.1086/345770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews GV, Bartholomeusz A, Locarnini S, et al. Characteristics of drug resistant HBV in an international collaborative study of HIV-HBV-infected individuals on extended lamivudine therapy. AIDS. 2006 Apr 4;20(6):863–870. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218550.85081.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheldon J, Camino N, Rodes B, et al. Selection of hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations in HIV-coinfected patients treated with tenofovir. Antivir Ther. 2005;10(6):727–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lada O, Gervais A, Branger M, et al. Quasispecies analysis and in vitro susceptibility of HBV strains isolated from HIV-HBV-coinfected patients with delayed response to tenofovir. Antivir Ther. 2012;17(1):61–70. doi: 10.3851/IMP1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitahata MM, Rodriguez B, Haubrich R, et al. Cohort profile: the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. Int J Epidemiol. 2008 Oct;37(5):948–955. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006 Jun;43(6):1317–1325. doi: 10.1002/hep.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hongthanakorn C, Chotiyaputta W, Oberhelman K, et al. Virological breakthrough and resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving nucleos(t)ide analogues in clinical practice. Hepatology. 2011 Jun;53(6):1854–1863. doi: 10.1002/hep.24318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Vries-Sluijs TE, Reijnders JG, Hansen BE, et al. Long-term therapy with tenofovir is effective for patients co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus. Gastroenterology. 2010 Dec;139(6):1934–1941. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Childs K, Joshi D, Byrne R, et al. Tenofovir-based combination therapy for HIV/HBV co-infection: factors associated with a partial HBV virological response in patients with undetectable HIV viraemia. AIDS. 2013 Jun 1;27(9):1443–1448. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32836011c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plaza Z, Aguilera A, Mena A, et al. Influence of HIV infection on response to tenofovir in patients with chronic hepatitis B. AIDS. 2013 May 10; doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328362fe42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson SJ, George J, Strasser SI, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate rescue therapy following failure of both lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil in chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2011 Feb;60(2):247–254. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez-Uria G, Ratcliffe L, Vilar J. Long-term outcome of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use against hepatitis B in an HIV-coinfected cohort. HIV Med. 2009 May;10(5):269–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews GV, Seaberg EC, Avihingsanon A, et al. Patterns and causes of suboptimal response to tenofovir-based therapy in individuals coinfected with HIV and hepatitis B virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 May;56(9):e87–94. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 4;359(23):2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters MG, Andersen J, Lynch P, et al. Randomized controlled study of tenofovir and adefovir in chronic hepatitis B virus and HIV infection: ACTG A5127. Hepatology. 2006 Nov;44(5):1110–1116. doi: 10.1002/hep.21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Thibault V, et al. Long-term incidence of hepatitis B virus resistance to lamivudine in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Hepatology. 1999;30(5):1302–1306. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Bommel F, de Man RA, Wedemeyer H, et al. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy for hepatitis B virus-monoinfected patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Hepatology. 2010 Jan;51(1):73–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.23246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baran B, Soyer OM, Ormeci AC, et al. Efficacy of tenofovir in patients with Lamivudine failure is not different from that in nucleoside/nucleotide analogue-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 Apr;57(4):1790–1796. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02600-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriconi F, Colombatto P, Coco B, et al. Emergence of hepatitis B virus quasispecies with lower susceptibility to nucleos(t)ide analogues during lamivudine treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007 Aug;60(2):341–349. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thio CL. Virology and clinical sequelae of drug-resistant HBV in HIV-HBV-coinfected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(3 Pt B):487–491. doi: 10.3851/IMP1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuma P, Bottecchia M, Sheldon J, et al. Prior lamivudine (LAM) failure may delay time to complete HBV-DNA suppression in HIV patients treated with tenofovir plus LAM. Hepatology. 2008;48(4 Suppl):740A–741A. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Audsley J, Arrifin N, Yuen LK, et al. Prolonged use of tenofovir in HIV/hepatitis B virus (HBV)-coinfected individuals does not lead to HBV polymerase mutations and is associated with persistence of lamivudine HBV polymerase mutations. HIV Med. 2009 Apr;10(4):229–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cortez KJ, Proschan MA, Barrett L, et al. Baseline CD4+ T-cell counts predict HBV viral kinetics to adefovir treatment in lamivudine-resistant HBV-infected patients with or without HIV infection. HIV Clin Trials. 2013 Jul-Aug;14(4):149–159. doi: 10.1310/hct1404-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunez M, Ramos B, Diaz-Pollan B, et al. Virological outcome of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-coinfected patients receiving anti-HBV active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006 Sep;22(9):842–848. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maylin S, Boyd A, Lavocat F, et al. Kinetics of hepatitis B surface and envelope antigen and prediction of treatment response to tenofovir in antiretroviral-experienced HIV-hepatitis B virus-infected patients. Aids. 2012 May 15;26(8):939–949. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328352224d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arendt E, Jaroszewicz J, Rockstroh J, et al. Improved Immune Status Corresponds with Long-Term Decline of Quantitative Serum Hepatitis B Surface Antigen in HBV/HIV Co-infected Patients. Viral Immunol. 2012 Nov 6; doi: 10.1089/vim.2012.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rehermann B. Immune responses in hepatitis B virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 2003 Feb;23(1):21–38. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonacini M, Louie S, Bzowej N, Wohl AR. Survival in patients with HIV infection and viral hepatitis B or C: a cohort study. AIDS. 2004 Oct 21;18(15):2039–2045. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain MK, Opio CK, Osuagwu CC, Pillai R, Keiser P, Lee WM. Do HIV care providers appropriately manage hepatitis B in coinfected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy? Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Apr 1;44(7):996–1000. doi: 10.1086/512367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]