Abstract

Basophils have been implicated in promoting the early development of TH2 cell responses in some murine models of TH2 cytokine-associated inflammation. However, the specific role of basophils in allergic asthma remains an active area of research. Recent studies in animal models and human subjects suggest that IgE may regulate the homeostasis of human basophil populations. Here, we examine basophil populations in children with severe asthma before and during therapy with the IgE directed monoclonal antibody omalizumab. Omalizumab therapy was associated with a significant reduction in circulating basophil numbers, a finding that was concurrent with improved clinical outcomes. The observation that circulating basophils are reduced following omalizumab therapy supports a mechanistic link between IgE levels and circulating basophil populations and may provide new insights into one mechanism by which omalizumab improves asthma symptoms.

Keywords: Asthma, Basophil, Omalizumab, IgE, Allergy

Introduction

The incidence of asthma continues to increase and represents a significant source of morbidity, mortality and healthcare cost (1). Allergic asthma is characterized by production of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13 by CD4+ T helper type 2 (TH2) cells, immunoglobulin E (IgE) production by B cells, and the recruitment of innate effector cell populations including eosinophils, mast cells and basophils to inflamed tissues. In addition to their role as late phase effector cells that migrate into inflamed tissues after the inflammatory response is established, basophils have been implicated in promoting the early development of TH2 cell responses (2). While the influence of basophils on the initiation and progression of allergic inflammation suggests that they may represent a viable therapeutic target, the specific role of basophils in allergic asthma remains an active area of research (3).

In addition to the well-established role of IgE antibodies in mediating the release of effector molecules from granulocyte populations, IgE molecules can influence other aspects of granulocyte homeostasis (4). For example, IgE promotes the population expansion of basophils from bone marrow-resident progenitor populations in murine models of allergic disease and helminth infection (5). Furthermore, elevated serum IgE levels correlate with increased frequencies of circulating basophils in patients, suggesting that IgE may regulate the homeostasis of human basophil populations (5). However, the effect of reducing IgE levels on the percentage and number of circulating basophils in the context of allergic disease remains unknown.

Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against IgE and an FDA–approved treatment for allergic asthma (6). Omalizumab blocks the interaction between IgE and the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) expressed on the surface of basophils and mast cells (6). Omalizumab therapy correlates with reduced IgE levels in serum (6, 7), reduced FcεRI expression on basophils (7) and altered IgE-mediated basophil activation including reduced numbers of FcεRI required for activation via IgE-crosslinking and reduced allergen-mediated histamine release (8–11). However, the quantitative effects of omalizumab therapy on circulating basophil populations are not well understood. Here, we show that circulating basophils are reduced following omalizumab therapy, a finding that may provide a better understanding of the pathophysiology of asthma as well as one mechanism through which omalizumab improves asthma symptoms.

Materials and methods

Study Organization

This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Participants and guardians signed informed consent. Inclusion criteria: age 5–18 years, severe asthma, body weight and IgE level compatible with omalizumab administration chart. Exclusion criteria: immunotherapy in the past year, history of malignancy, immunodeficiency, autoimmune condition, anaphylaxis, or β-blocker use. Dose and frequency of omalizumab administration was determined by the dosing administration chart as provided by Genentech/Novartis. 7 subjects were dosed every two weeks, 2 subjects were dosed monthly. Asthma symptom assessments were administered.

Flow Cytometry

Blood samples were obtained before and during therapy. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll (GE) gradient, stained with anti-human fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against 2D7, CD11c, CD19, CD56, CD117, CD123, FcεRIα, IgE or TCRαβ (BD Bioscience, eBioscience), fixed with 4% PFA, and acquired on an LSR II using DiVa software (BD Bioscience) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Statistical Analysis

12 subjects were enrolled in the study, 3 were lost to follow-up and 1 outlier was deemed significant using the extreme studentized deviate method (coefficient of variation with outlier = 672.31%, coefficient of variation with outlier =132.94%) and excluded from the analysis. Significance of the remaining 8 data-points was determined using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results and Discussion

Clinical characteristics of the study subjects are presented in Table 1. Twelve subjects, aged 7–16 years, with severe persistent asthma were enrolled in the study. Three patients were lost to follow-up. The mean IgE level of the remaining subjects was 969 IU/mL (range 137–2510 IU/mL). Omalizumab dose and administration frequency was determined by the drug manufacturers dosing administration chart. There was no correlation between monthly or bimonthly dosing schedule and measured outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study subjects.

| Characteristic | Omalizumab (n=9) |

|---|---|

| Age (y), mean (range) | 12 (9–17) |

| Male sex (%) | 56 |

| Concurrent allergic rhinitis (%) | 100 |

| Concurrent atopic dermatitis (%) | 44 |

| Therapy with LABA/ICS# (%) | 100 |

| Days of asthma symptoms per week*, mean (±SEM) | 3 (±1) |

| Asthma symptom-related physician visits*, mean (±SEM) | 2 (±1) |

| Asthma symptom-related ED visits*, mean (±SEM) | 2 (±1) |

| Days of albuterol use per week*, mean (±SEM) | 3 (±1) |

| Prednisone courses*, mean (±SEM) | 3 (±1) |

| Total IgE (IU/mL), mean (±SEM) | 969 (±251) |

| Omalizumab dose (mg), mean (±SEM) | 333 (±13) |

Long acting beta agonist/Inhaled corticosteroid

12 months preceding the start of Omalizumab treatment

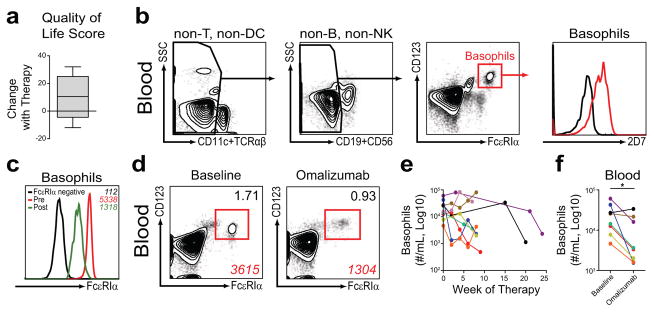

To determine the influence of omalizumab therapy on asthma control, a survey of asthma symptoms was utilized. Consistent with previous reports (6), omalizumab therapy was associated with an average ten point improvement in asthma control (Figure 1a). To test whether omalizumab therapy was associated with alterations in circulating basophil populations, we examined basophil frequencies and total numbers in the blood of subjects prior to and during therapy. Basophils were identified by flow cytometric analysis as being negative for surface markers associated with B cells, NK cells, T cells and dendritic cells, and positive for the basophil-associated surface markers CD123 and FcεRI. In addition, basophil identification was confirmed by intracellular expression of the basophil-specific granular protein 2D7 (12) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Omalizumab therapy results in improved asthma control and reduced frequencies and numbers of circulating basophils in asthmatic children. (a) Change in asthma symptom/quality of life score with omalizumab therapy (n=5). (b) Identification of blood basophils from asthmatic subjects by flow cytometric analysis as CD11c−, TCRαβ−, CD19−, CD56−, CD123+, FcεRIα+, 2D7+ cells. 2D7 staining of basophils (red) was compared to FcεRIα+, CD123− cell populations (black). (c) Representative flow cytometric analysis of blood basophils from asthmatic subjects before and during therapy illustrating the MFI (italics) of FcεRIα expression of basophils pre-treatment (red, 5338) and post-treatment (green, 1318) compared to FcεRIα-negative cells (black, 112). (d) Representative percentage (black) and MFI (red) of blood basophils from asthmatic subjects before (baseline) and after (omalizumab) therapy. (e) Number of basophils in blood from asthmatic subjects over the course of therapy. (f) Basophil numbers before (baseline) and after (omalizumab) an average of eight weeks of therapy (mean = 7.8 weeks, range = 4–21 weeks) (*, P ≤ 0.05; n=8).

Consistent with a previous report (7), we observed a 70–80% reduction in the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of FcεRI on circulating basophil populations following the initiation of omalizumab therapy (Figure 1c). Despite a 70–80% reduction in the MFI of FcεRI expression, human basophil populations exhibited a 10 fold higher MFI of FcεRI expression compared to FcεRI negative cell populations (Figure 1c) and were readily identifiable based on their expression of FcεRI (7) and CD123 (Figure 1d). Compared to samples collected prior to therapy, the percentage of blood basophils was reduced after the initiation of omalizumab (Figure 1d). While total white blood cell numbers did not change over the course of therapy (data not shown), there was an average reduction in the total number of circulating basophils (basophils/mL) after initiating omalizumab therapy with variability in the magnitude and timing of the reduction when comparing individual subjects (Figure 1e). Based on our previous studies in animal models (5), we hypothesized that significant reductions in basophil numbers would occur after four to eight weeks of therapy. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed a significant reduction in the total number of circulating basophils after 2 omalizumab injections or an mean duration of therapy of 8 weeks (range 4–21 weeks) (Figure 1f). Together, these findings indicate that circulating basophil frequencies and numbers are reduced following omalizumab therapy.

We report that on average circulating basophil frequencies and numbers in asthmatic children are reduced with omalizumab therapy and that reductions in circulating basophils were concurrent with improved asthma control. However, two subjects in our study did not have a reduction in circulating basophils at the time point measured. As such, a decline in circulating basophil responses may not always parallel omalizumab therapy or individual clinical improvement. Further investigation is warranted to determine whether these subjects who do not display reductions in circulating basophils represent a clinically relevant sub-population with implications for future treatment failure. A study by Lin et al. reported that omalizumab therapy does not alter circulating basophil numbers (7). Our observations may differ from the Lin et al. study as a result of differences in adult versus pediatric patient populations, study design or new 9 color flow cytometric techniques we employed that may identify human basophil populations with higher resolution than previously possible with 4 color flow cytometric techniques (Lin et. al). Though our study is limited by the absence of placebo group, the observation that circulating basophil frequencies and numbers are reduced following omalizumab therapy is consistent with previous findings in allergic patients and animal models, and supports a mechanistic link between reduced systemic IgE levels and lower circulating basophil populations. This finding may contribute to a better understanding of the pathophysiology of asthma as well as one mechanism through which omalizumab may improves asthma symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments and Funding

We thank James M. Corry, Michael Comeau and Angela Haczku for critical reading of this manuscript, Terri Faye Brown-Whitehorn, Jennifer Heimall, Benjamin P. Soule, Rose Stinson, and Paulette Devine for patient care, the Biostatistics and Data Management Core of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and the Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Resource Laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania. Spergel Lab support: The Stuart E. Starr Chair in Pediatrics, the Department of Defense (W81XWH-11-1-0507), and the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (UL1-RR024134). Artis Lab support: The National Institutes of Health (AI061570, AI087990, AI074878, AI083480, AI102942, AI095466, AI095608, AI097333 and AI106697 to D.A.), F32-AI085828 to M.C.S., T32-AI060516 and F32-AI098365 to E.D.T.W., the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the NIH/NIDDK P30 Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases (P30-DK050306), and the Joint CHOP-Penn Center in Digestive, Liver and Pancreatic Medicine.

Footnotes

Author contributions

D.A.H, M.S., D.A. and J.M.S designed the research; D.A.H., M.S., K.R., and E.D.T.W performed the research; D.A.H, M.S., D.A. and J.M.S analyzed the data; and D.A.H, M.S., D.A. and J.M.S wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA, King M, Minor P, Bailey C, et al. National surveillance for asthma--united states, 1980–2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007 Oct 19;56(8):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siracusa MC, Comeau MR, Artis D. New insights into basophil biology: Initiators, regulators, and effectors of type 2 inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Jan;1217:166–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05918.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenstein LM, Bochner BS. The role of basophils in asthma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;629:48–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton OT, Oettgen HC. Beyond immediate hypersensitivity: Evolving roles for IgE antibodies in immune homeostasis and allergic diseases. Immunol Rev. 2011 Jul;242(1):128–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill DA, Siracusa MC, Abt MC, Kim BS, Kobuley D, Kubo M, et al. Commensal bacteria-derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation. Nat Med. 2012 Mar 25;18(4):538–46. doi: 10.1038/nm.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milgrom H, Fick RB, Jr, Su JQ, Reimann JD, Bush RK, Watrous ML, et al. Treatment of allergic asthma with monoclonal anti-IgE antibody rhuMAb-E25 study group. N Engl J Med. 1999 Dec 23;341(26):1966–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912233412603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin H, Boesel KM, Griffith DT, Prussin C, Foster B, Romero FA, et al. Omalizumab rapidly decreases nasal allergic response and FcepsilonRI on basophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Feb;113(2):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckman JA, Sterba PM, Kelly D, Alexander V, Liu MC, Bochner BS, et al. Effects of omalizumab on basophil and mast cell responses using an intranasal cat allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Apr;125(4):889, 895.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saini SS, Macglashan DW., Jr Assessing basophil functional measures during monoclonal anti-IgE therapy. J Immunol Methods. 2012 Jun 1; doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macglashan DW, Jr, Saini SS. Omalizumab increases the intrinsic sensitivity of human basophils to IgE-mediated stimulation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Oct;132(4):906, 11.e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noga O, Hanf G, Kunkel G, Kleine-Tebbe J. Basophil histamine release decreases during omalizumab therapy in allergic asthmatics. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2008;146(1):66–70. doi: 10.1159/000112504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kepley CL, Craig SS, Schwartz LB. Identification and partial characterization of a unique marker for human basophils. J Immunol. 1995 Jun 15;154(12):6548–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]