Abstract

Shifting visual focus based on the perceived gaze direction of another person is one form of joint attention. The present study investigated if this socially-relevant form of orienting is reflexive and whether it is influenced by age. Green and Woldorff (2012) argued that rapid cueing effects (faster responses to validly-cued targets than to invalidly-cued targets) were limited to conditions in which a cue overlapped in time with a target. They attributed slower responses following invalid cues to the time needed to resolve incongruent spatial information provided by the concurrently-presented cue and target. The present study examined orienting responses of young (18-31 years), young-old (60-74 years), and old-old adults (75-91 years) following uninformative central gaze cues that overlapped in time with the target (Experiment 1) or that were removed prior to target presentation (Experiment 2). When the cue and target overlapped, all three groups localized validly-cued targets faster than invalidly-cued targets, and validity effects emerged earlier for the two younger groups (at 100 ms post cue onset) than for the old-old group (at 300 ms post cue onset). With a short duration cue (Experiment 2), validity effects developed rapidly (by 100 ms) for all three groups, suggesting that validity effects resulted from reflexive orienting based on gaze cue information rather than from cue-target conflict. Thus, although old-old adults may be slow to disengage from persistent gaze cues, attention continues to be reflexively guided by gaze cues late in life.

Keywords: aging, attention, reflexive orienting, gaze cues, cue duration, time course, old-old

Shifts in spatial attention are reflexive when they are elicited rapidly by stimuli uninformative of an upcoming object's location. Originally thought to occur specifically in response to peripherally-presented stimuli, reflexive orienting has also been demonstrated in response to centrally-fixated directional stimuli (e.g., arrow cues and gaze cues; Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Ristic, Friesen, & Kingstone, 2002; Tipples, 2002). The present study examined the nature of spatial orienting triggered by gaze cues. There is an evolutionary and social advantage associated with rapidly shifting attention in response to a person's gaze; responding to threats or resources in the environment identified by a companion could lead to faster evasive or approach reactions. The gaze direction of another person is also an important nonverbal cue in social communication. In childhood, orienting in response to gaze direction promotes the development of joint attention - the ability to coordinate attention with another observer, which facilitates learning, language development, and social competence (see reviews by Frischen, Bayliss, & Tipper, 2007; Mundy & Newell, 2007). Surprisingly, although developmental patterns of gaze-based orienting and joint attention have been investigated in infancy and childhood, the developmental changes later in life have only begun to be explored. Joint attention as guided by gaze direction likely remains important for cooperative cognition among older adults. The purpose of the present study was twofold: to explore the reflexive orienting properties of gaze cues, and to assess adult age patterns in gaze-triggered orienting. In the following sections, we review current evidence regarding reflexive orienting in response to central spatial cues and age-related modifications of these orienting patterns.

Reflexive Orienting to Central Spatial Cues

Researchers have traditionally used two types of cues to measure spatial orienting (Posner, 1980; Posner & Cohen, 1984): peripheral cues that are presented outside the current attentional focus and are uninformative of the target location, and central arrow cues that are presented at visual fixation and provide informative directional information (e.g., they point toward the target location on a high percentage of trials; Posner & Cohen, 1984). Unique temporal orienting patterns are associated with uninformative peripheral cues and informative arrow cues (for a review, see Klein, Kingstone, & Pontefract, 1992). When presented peripherally, valid cues (cues that indicate the location of the upcoming target) lead to faster responses to targets than invalid cues, and this validity effect develops rapidly (as early as 50 to 100 ms post-cue) and then diminishes (and later reverses). Cueing effects for informative arrow cues (valid RTs < invalid RTs) develop more slowly and are maintained at longer time intervals. The different cuing patterns have been interpreted to reflect reflexive and volitional orienting (Jonides, 1981). Attention is reflexively drawn to the location of peripheral cues, leading to rapid but short-lived facilitation effects. In the case of informative arrow cues, attention is voluntarily (and thus, less quickly) directed to (and maintained at) locations indicated by the central symbolic cues due to the predictive nature of the cues.

Although it was long assumed that central arrow cues directed attention based on their predictive properties, recent research has revealed that uninformative arrows also bias spatial attention (Hommel, Pratt, Colzato, & Godijn, 2001; Kingstone, Smilek, Ristic, Friesen, & Eastwood, 2003; Ristic et al., 2002; Tipples, 2002). Even when the target was as likely to be presented at the uncued location as at the cued location (50% predictive), validity effects have been observed at short cue-target SOAs (100-300 ms), consistent with reflexive orienting.

Following a hallmark study by Friesen and Kingstone (1998), multiple studies have demonstrated reflexive orienting patterns for gaze cues (e.g., Driver et al., 1999; Friesen, Moore, & Kingstone, 2005; Kingstone, Tipper, Ristic, & Ngan, 2004; Ristic, Wright, & Kingstone, 2007). For example, Ristic and colleagues (2002) presented participants with a schematic face or an arrow that looked/pointed to the left or right. Although the cues were uninformative (50% predictive), the validity effect, indistinguishable for gaze and arrow cues, developed rapidly (at a cue-target SOA of 195 ms) and diminished at longer cue-target intervals (600 and 1,005 ms). Although the temporal dynamics of cueing patterns were similar for arrow and gaze cues, there is evidence that gaze-based orienting is more reflexive than arrow-based orienting (Friesen, Ristic, & Kingstone, 2004; Ristic & Kingstone, 2005). For instance, gaze-initiated orienting is not as strongly affected by top-down contingencies as arrow-initiated orienting (Ristic et al., 2007).

Green and Woldorff (2012) observed that the majority of studies that reported reflexive orienting triggered by central directional cues used a stimulus sequence with cue-target temporal overlap (e.g., Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Quadflieg, Mason, & Macrae, 2004; Ristic et al., 2002; but c.f. Friesen & Kingstone, 2003; Ristic et al., 2007; Tipples, 2002). They argued that the persistent cue may have induced stimulus conflict between the cue and target on invalidly-cued trials, and that this conflict slowed target processing. To test this non-attentional explanation for validity effects, the researchers compared the effects of directionally-predictive (80% valid) arrows that remained visible upon target presentation (long-duration cues) with the effects of directionally-predictive arrows that were presented briefly (50 ms) and were removed prior to target presentation (short-duration cues). With short-duration cues, validity effects were not observed at short cue-target SOAs (0 or 100 ms) but were found at SOAs equal to or longer than 300 ms, consistent with volitional orienting in response to a predictive cue. With long-duration cues, validity effects were observed at 0 and 100 ms, not at 200 ms, and again at 300 ms and longer. This biphasic pattern suggested that orienting was volitional at longer SOAs, but the effects at the short SOAs were unlikely to be attentional, particularly given validity effects with simultaneous cue-target presentation (0 ms SOA). A second experiment, which added neutral cues (double arrows), demonstrated that the validity effects associated with long-duration cues consisted of costs only (slower responses to an invalidly-cued target than to a neutrally-cued target) at early cue-target intervals and both benefits (faster responses to a validly-cued target than to a neutrally-cued target) and costs at later intervals. Thus, the pattern overall was consistent with interference between a cue and target when the two stimuli were presented concurrently and contained conflicting spatial information (on invalid trials), and this conflict led to slowed responses that mimicked reflexive orienting patterns. The lack of validity effects at short SOAs when the temporal overlap was removed suggested that reflexive orienting did not contribute to the observed cueing patterns. More recently, Green, Gamble, and Woldorff (2013) provided additional evidence for a spatial-incongruency explanation, this time using gaze cues as well as arrow cues. Cueing effects were absent at short and long SOAs when nonpredictive, short-duration gaze or arrow cues were presented. With long-duration nonpredictive cues, there were cueing effects (consistent with RT costs but not benefits) at the 0 and 100 ms SOAs (but not at 300 or 500 ms SOAs), again consistent with response slowing resulting from conflicting spatial information from the cue and target .This set of findings call into question the reflexive nature of orienting in response to centrally directional cues.

Age-Related Changes in Reflexive Orienting to Central Cues

Research on age-related changes in reflexive orienting triggered by central cues is limited. Studies of arrow-triggered orienting have primarily assessed volitional orienting to informative arrows and found orienting to be largely intact with age (Folk & Hoyer, 1992; Hartley, Kieley, & Slabach, 1990; Lincourt, Folk, & Hoyer, 1997; Tellinghuisen, Zimba, & Robin, 1996). In a recent study (Langley, Friesen, Saville, & Ciernia, 2011), we examined reflexive orienting in response to uninformative central arrows and found validity effects at short cue-target SOAs (100 and 300 ms) that were evident even when the cue did not overlap with the target (Experiment 2). There was no evidence of an age-related reduction in the orienting response; in fact, older adults’ validity effects were greater than those of young adults at the 300 ms SOA, suggesting longer maintenance of orienting. Thus, under conditions that promoted reflexive orienting (short cue-target intervals, uninformative cues that did not overlap temporally with the target), we found that older adults automatically shifted attention based on central arrow information.

Two studies have examined age-related changes in orienting to central gaze cues, although task conditions were such that orienting was likely volitional, or at least not clearly reflexive. Slessor, Phillips, and Bull (2008, Experiment 2) examined older adults’ orienting responses to informative gaze cues (which predicted target location on 67% of the trials). The eye gaze of photographed young adult faces gradually moved to the left or right in a morphing progression lasting 220 ms. The face was removed upon target onset. Older adults showed significant validity effects that were smaller than those of young adults, suggesting an age-related reduction in gaze-triggered orienting. To determine whether the age of the gazing face impacted orienting, Slessor, Laird, Phillips, Bull, and Filippou (2010) showed participants photographic images of young and older faces that gazed to the left or right (without the morphing progression). The gaze cues (which remained present until the response) were uninformative of target location, but the cue-target SOA (500 ms) was longer than typically used to examine reflexive orienting. Young adults had greater validity effects for young faces than older faces (20 ms and 12 ms, respectively). Older adults’ validity effects were uninfluenced by the age of the faces (9 ms and 13 ms for young and older faces, respectively). Thus, the age-related reduction in validity effects was specific to gaze shifts portrayed in young faces, which may have accounted for the age differences found in the Slessor et al. (2008) study. Together, the findings indicate that older adults shift spatial attention in response to gaze cues, although there may be an age-related reduction in validity effects specific to gaze shifts initiated by young adult faces. Age patterns under conditions that more strongly encourage reflexive orienting (with uninformative cues and short cue-target SOAs) and that avoid age-consistency effects (bigger orienting effects for same-age faces) have yet to be assessed.

The Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether orienting in response to central gaze cues is indeed reflexive, and whether this socially-important cue continues to efficiently guide attention later in life. In Experiment 1, we tested participants on a gaze cueing paradigm that encouraged reflexive orienting (Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Friesen et al., 2005; Ristic et al., 2002). A target appeared to the left or right of a central gaze cue, and participants made a speeded left-right localization response. The uninformative (50% predictive) gaze cue (eyes shifted to the left or right) preceded target onset by 100, 300, 600, or 1,000 ms. The cue and target remained present until the participant's response. To avoid age-consistency effects induced by the cue face (Slessor et al., 2010), we used a schematic (age-neutral) face rather than a photographed face. Because of the concerns raised by Green and Woldorff (2012) with interpreting the basis of validity effects as attentional when the cue and target overlap in time (and thus introduce cue-target conflict), we limited the duration of the cue to 50 ms in Experiment 2 and removed the cue prior to target presentation.

In both experiments, we predicted that participants would show validity effects (faster responses to targets at gazed-at locations than those at uncued locations) that reflected reflexive orienting. Validity effects would develop rapidly (by 100 ms post-cue), but because cues would not be predictive of target location, validity effects would diminish with increasing cue-target SOA. We predicted that validity effects would be evident even when the cue and target were separated in time (Experiment 2). Although it was possible that cue-target stimulus conflict would contribute to cueing patterns in Experiment 1 (Green & Woldorff, 2011), we predicted that reflexive orienting would independently influence behavior because other studies have found validity effects when the cue and target were presented without overlap (McKee, Christie, & Klein, 2007; Ristic et al., 2007; Tipples, 2002). However, if stimulus conflict alone accounted for validity effects in Experiment 1, then those effects would disappear in Experiment 2.

In addition to young adults (ages 18-35 years), we tested two older adult groups (young-old adults, 60-74 years; old-old adults, 75+ years) because evidence indicates that spatial orienting patterns continue to change late in life (Greenwood & Parasuraman, 1994; Greenwood, Parasuraman, & Haxby, 1993; Langley et al., 2011). Greenwood and colleagues (1993, 1994) found that on a letter discrimination task, validity effects triggered by uninformative peripheral cues and informative arrow cues were greater for old-old adults than for young-old adults (although orienting did not vary by age on a simpler target detection task). We found, using a location discrimination task, that old-old adults’ reflexive orienting pattern to uninformative peripheral onset cues and central arrow cues was identical to that of young-old adults, except that limiting cue duration did not modify orienting for old-old adults as it did for young-old adults. Old-old adults continued to show enhanced and extended validity effects at early cue-target intervals, which implied greater cue disengagement deficits for old-old adults (Langley et al., 2011).

Our predictions regarding age patterns were tentative because of equivocal and limited evidence on older adults’ reflexive orienting in response to central directional cues. Slessor and colleagues (2008, 2010) found that older adults successfully oriented to spatial locations based on gaze cues, but the strength of the orienting effect diminished with age when gaze cues were presented on young faces. In addition, the task conditions used to assess orienting (with predictive cues and/or long cue-target SOAs) did not encourage reflexive orienting. Older adults have demonstrated reflexive orienting in response to uninformative arrows (Langley et al., 2011). Based on this limited evidence, we predicted that older adults would reflexively orient to locations based on gaze cue information. Because the stimulus faces were age-neutral (reducing the possibility of age consistency effects), we expected that validity effects would be at least as great for older adults as for young adults. If difficulty in cue disengagement increases with age, the age-related increase in validity effects would be particularly true in Experiment 1, when the cue and target remained present until a response was made.

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, gaze cues were presented on a schematic face with a neutral expression. The eyes gazed to the left or to the right, and after a cue-target SOA of 100, 300, 600, or 1,000 ms, the target appeared at either the cued or uncued location. The gaze cue remained present until the participant made a left-right localization response. As found with previous gaze cue studies (Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Ristic et al., 2002), we predicted validity effects at the early SOAs (100 and 300 ms), reflecting reflexive orienting to the target, with decreasing validity effects at longer SOAs.

Method

Participants

Forty young adults (18-31 yrs; 24 women, 16 men), 40 young-old adults (60-74 yrs; 25 women, 15 men), and 40 old-old adults (75-92 yrs; 25 women, 15 men) participated in Experiment 1. Young adults were recruited from psychology courses and received course credit. Older adults were recruited from the Fargo-Moorhead community and received $10 for participating. All individuals had at least a high school education and were native English speakers. Participants had corrected near visual acuity of 20/40 or better as assessed by a Snellen eye chart (Precision Vision, La Salle, IL) and were free from medical conditions that could affect cognitive functioning (e.g., stroke, dementia, or drug and alcohol abuse) according to self-report (Christensen, Moye, Armson, & Kern, 1992). All included participants scored 9 points or lower on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; Yesavage et al., 1982), indicating minimal depressive symptoms, and 26 points or higher on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), indicating no demonstrable signs of significant cognitive impairment. Demographic and screening data for included participants are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics for Experiments 1 and 2

| Experiment 1 |

Experiment 2 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|||||||||

| YA |

YO |

OO |

YA |

YO |

OO |

YA |

YO |

OO |

YA |

YO |

OO |

|

| Age (yrs) | 20.3* | 66.6 | 78.9* | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 20.2* | 67.0 | 79.6* | 2.4 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| Education (yrs) | 14.0* | 15.3 | 14.7 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 13.8* | 15.2 | 15.0 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| GDS (30 max) | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| WASI Vocab. (80 max) | 58.8* | 68.5 | 65.8 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 8.8 | 58.4* | 66.0 | 64.0 | 5.5 | 8.4 | 6.7 |

| Snellen acuity (20/___) | 15.4* | 22.3 | 24.5 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 15.4* | 25.2 | 25.5 | 3.6 | 6.4 | 6.6 |

| MMSE (30 max) | 29.3 | 29.3 | 28.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 29.5 | 29.5 | 29.1 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

Note. SD = standard deviation. YA = young adults, YO = young-old adults, OO = old-old adults; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale. Maximum score is 30, with a higher score indicating more endorsed symptoms of depression. WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999). Maximum score on the vocabulary subscale is 80 points, with a higher score indicating better performance. Snellen acuity = denominator of the Snellen fraction for corrected near vision. A smaller number indicates better vision. MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination. Maximum score is 30 points, with a higher score indicating better performance.

mean scores differed significantly from the young-old adult group according to a Student-Newman-Keuls t test, p < .05

Materials and stimuli

Stimuli were presented on a 17 in. color monitor (refresh rate of 85 Hz) controlled by a PC computer with a Pentium 4 processor. A chin rest maintained participants’ viewing distance at 40 cm. Participants responded to stimuli using a PST Serial Response Box (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). We used E-Prime 1.1 (Psychology Software Tools) to develop and run the experiment. Stimuli were black line drawings presented against a white background. The initial fixation display consisted of a circle with a diameter of 14.5° of visual angle positioned in the middle of the monitor. In the circle, there was a schematic face with a neutral expression. Two empty circles 1.9° in diameter served as the eyes. The central circle was flanked to the left and right by two empty 2.9° squares at a distance of 17.8° from the circle (center to center). The gaze cue overlaid the fixation display and consisted of two black filled circles with diameters of 1.3° displaced to the left or the right, serving as the pupils for the eyes. A black filled circle, 1.7° in diameter, served as the target stimulus and was presented in the center of one of the two outer squares.

Design and procedure

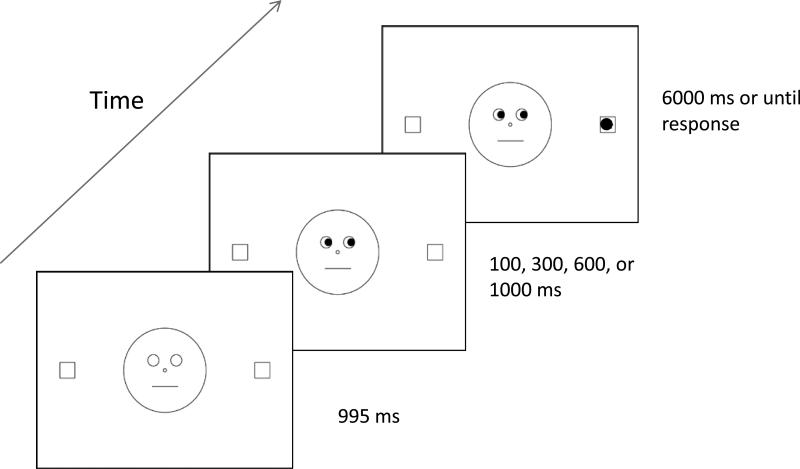

The testing session (including consent, screening, and computer task) lasted approximately 1 hour. The experimenter explained the task to participants using verbal instructions and a drawn representation of the stimulus events. As depicted in Figure 1, a trial began with the fixation display presented for 995 ms, which was followed by the cue display (pupils shifted to the left or right). After approximately 100, 300, 600, or 1,000 ms (as constrained by the refresh rate of the monitor; actual values: 117.6, 317.6, 611.7, and 1011.7 ms), the target appeared in either the left or right outer square. The cue and target remained on the screen until the participant responded or 6,000 ms had elapsed. Participants pressed one of two buttons (left or right) on the response box to indicate the target's location. They were instructed to respond as quickly as possible but not at the expense of accuracy. They were also told that the face's gaze direction (left or right) did not predict the target location. Participants were told to keep their eyes fixated on the nose of the face throughout the trial, but eye movements were not monitored. Participants completed two blocks of 80 trials, for a total of 160 experimental trials, presented randomly and with equal probability for SOA, cue validity, and cue and target location. Before starting each block, participants completed eight practice trials that were randomly selected from the experimental trials.

Figure 1.

Trial sequence for Experiment 1. The stimuli are not drawn to scale.

Results

Mean response times (RTs) as a function of age group, cue validity, and cue-target SOA are presented in Table 2. Errors (incorrect responses, anticipatory responses, and failures to respond) were rare within each condition for each age group (on average, less than 2%). RTs that were less than 150 ms or more than 2,500 ms (less than 1% of trials per group) were considered outliers and removed. For the remaining trials, median RTs were calculated for correct responses and submitted to a 3 × 2 × 4 mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with age group (young adults, young-old adults, and old-old adults) as the between-subjects variable and cue validity (valid and invalid) and cue-target SOA (100, 300, 600, and 1,000 ms) as the within-subject variables. For follow-up analyses of variables with more than two levels, we used Student Newman Keuls (SNK) post hoc tests.

Table 2.

Response Times (ms) as a Function of Age Group, Cue Validity, and SOA (ms) for Experiment 1.

| Young Adults |

Young-Old Adults |

Old-Old Adults |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOA |

V |

I |

I-V

|

V |

I |

I-V

|

V |

I |

I-V

|

| RT means | |||||||||

| 100 | 370 | 387 | 17 * | 475 | 498 | 23 * | 520 | 525 | 5 |

| 300 | 335 | 342 | 7 * | 445 | 464 | 19 * | 472 | 493 | 21 * |

| 600 | 326 | 335 | 9 * | 429 | 430 | 1 | 441 | 447 | 6 † |

| 1000 | 323 | 329 | 6 * | 413 | 426 | 13 * | 445 | 446 | 1 |

| RT SDs | |||||||||

| 100 | 63 | 58 | 31 | 75 | 79 | 29 | 92 | 86 | 34 |

| 300 | 59 | 55 | 20 | 79 | 83 | 23 | 85 | 82 | 27 |

| 600 | 53 | 60 | 18 | 95 | 91 | 31 | 87 | 88 | 23 |

| 1000 | 55 | 55 | 16 | 82 | 79 | 31 | 89 | 89 | 27 |

Note. RT = response time, SOA = stimulus onset asynchrony between the gaze cue and target, V = validly-cued target, I = invalidly-cued target, I-V = Invalid RT minus Valid RT (mean difference score).

the difference score was significantly greater than 0 by t test,p < .05.

the difference score was marginally greater than 0 by t test, .05 <p < .10.

All main effects were significant: age group, F(2, 117) = 35.10, p < .001, cue validity, F(1, 117) = 69.09, p < .001, and cue-target SOA, F(3, 351) = 218.19, p < .001. SNK analyses indicated that old-old adults and young-old adults were slower to respond than young adults (474, 447, and 343 ms, respectively), ps < .05, but RTs did not differ significantly between the two older groups, p > .05. The cue validity effect indicated that participants responded faster to validly-cued targets (416 ms) than to invalidly-cued targets (427 ms). The main effect of cue-target SOA reflected an overall decrease in RT as SOA increased (462, 425, 401, and 397 ms for SOAs of 100, 300, 600, and 1,000 ms, respectively), a standard foreperiod effect (Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Posner, 1978).

We found two significant two-way interactions. The Age Group × SOA interaction, F(6, 351) = 5.94, p < .001, reflected a greater decrease in RTs with increasing SOA for old-old adults than for the other two age groups. The Cue Validity × SOA interaction, F(3, 351) = 5.99, p < .001, reflecting temporal modulation of validity effects, was examined with separate one-way ANOVAs assessing cue validity effects at each SOA. Validity effects (valid RTs < invalid RTs) were significant at all four SOAs, all Fs > 5.8, all ps < .05. Post hoc SNK analyses on the validity effect difference scores (invalid RT minus valid RT) revealed that validity effects were greater at the 100 ms and 300 ms SOAs (15 ms and 16 ms, respectively) than at the 600 ms and 1,000 ms SOAs (5 ms and 6 ms, respectively).

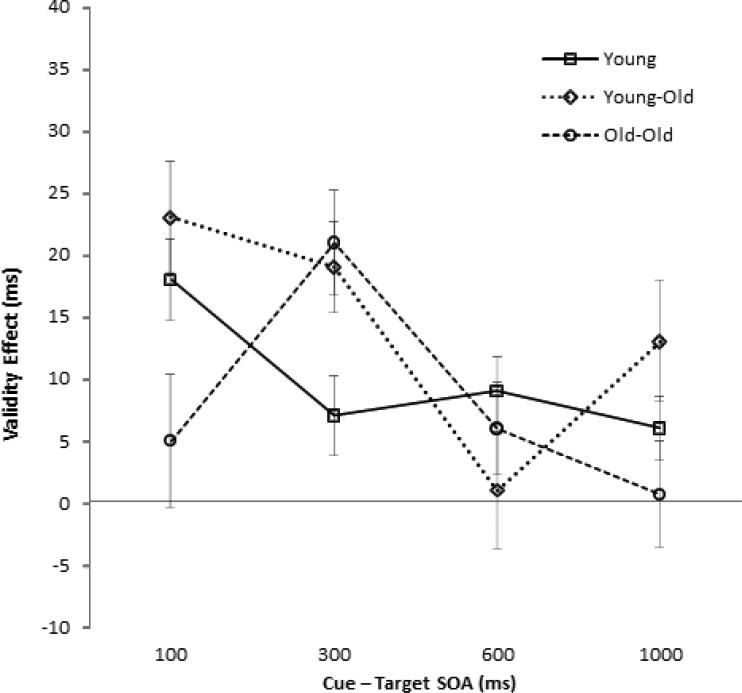

Finally, we found a significant Age Group × SOA × Cue Validity interaction, F(6, 351) = 3.56, p = .002, which is illustrated in Figure 2. When examined separately, each of the three age groups showed significant Cue Validity × SOA interactions, all Fs > 3.1, all ps < .05. As assessed with SNKs comparing validity effect difference scores across the SOAs, young adults had greater validity effects at the 100 ms SOA than at the 300, 600, or 1,000 ms SOAs. Young-old adults had greater validity effects at the 100 and 300 ms SOAs than at the 600 ms SOA (the 1,000 ms SOA was not significantly different from the other SOAs). Finally, old-old adults showed greater validity effects at the 300 ms SOA than at the 100, 600, or 1,000 ms SOAs. Age differences in validity effects were observed at the 100 ms SOA, F(2, 117) = 4.21, p =.017, and at the 300 ms SOA, F(2, 117) = 4.24, p = .017. SNK analyses showed that at 100 ms the young and young-old adults had greater validity effects than the old-old adults, and at 300 ms the two older groups had greater validity effects than the young adults.

Figure 2.

Cueing effects (invalid response times [RTs] minus valid RTs) for each age group across the four stimulus onset asynchronies (SOAs) for Experiment 1.

To address the possibility that general slowing affected group differences in validity effects (Faust, Balota, Spieler, & Ferraro, 1999), we conducted a second set of analyses on RTs that were transformed to account for slowing (Madden, Whiting, Cabeza, & Huettel, 2004). Brinley plot analyses (Cerella, 1994) were used to determine the regression equations that best characterized the linear relationship between the eight Cue Validity × SOA condition means of old-old adults with those of the other two groups. We used the resulting equations (see Equations 1 and 2 below) to transform the data of young and young-old participants (i.e., we introduced slowing effects to their data). The assumption of this approach was that if age interactions remained significant after transforming the data, then the interactions were likely representative of cognitive or perceptual effects, largely independent of general slowing. The transformed data were submitted to the same 3 × 2 × 4 ANOVA used in the original analysis. Results indicated that there was no longer a main effect of age, F < 1, as expected. The main effects of cue validity, F(1, 117) = 76.98, p < .001, and SOA, F(3, 351) = 225.30, p < .001, remained significant, as did the three-way interaction of age group, cue validity, and SOA, F(6, 351) = 3.39, p = .003. As in the original analysis, age differences in the validity effects at the 100 ms SOA, F(2, 117) = 5.52, p = .005, reflected greater validity effects for the young and young-old adults than for the old-old adults. The age difference at the 300 ms SOA was now marginally significant, F(2, 117) = 2.49, .p = .087, and SNK analyses showed that the validity effects of the two older groups did not differ significantly from those of the young adults.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Discussion

We predicted that all three age groups would orient attention in response to gaze direction. When presented 300 ms following cue onset, all three age groups responded more quickly to targets at gazed-at locations than to targets at the opposite locations, and these validity effects were greater in magnitude for the two older groups than for young adults. However, the age difference did not statistically withstand a data transform that took into account generalized slowing, suggesting that non-attentional factors contributed to the enhanced validity effects for older adults. Young adults and young-old adults showed cue validity effects (comparable in magnitude) at an even shorter cue-target interval of 100 ms, consistent with reflexive orienting in response to gaze shifts (Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Ristic et al., 2002).

Surprisingly, old-old adults did not show validity effects at 100 ms. One possible explanation for this delayed orienting effect is that old-old adults were slower to process gaze cue information than the other two age groups, thus delaying orienting. A second possibility is that old-old adults had difficulty disengaging attention from the gaze cue itself to orient toward the gazed-at location, and that the 300 ms SOA, but not the 100 ms SOA, provided sufficient time to disengage and shift attention before the target was presented. These two possibilities were explored in Experiment 2. The cueing pattern for old-old adults was not consistent with past findings with arrow and peripheral cues of enhanced validity effects for this age group (Greenwood et al., 1993, 1994; Langley et al., 2011), suggesting that different cue types are associated with unique age patterns.

Experiment 2

To investigate whether the validity effects observed in Experiment 1 (faster responses to validly-cued targets than to invalidly-cued targets at short cue-target SOAs) were best explained by reflexive orienting in response to central gaze cues or interference from conflicting cue-target information, we shortened the duration of the cue (to 50 ms) and removed temporal overlap with the target. If validity effects remained, they could not be due to conflicting information from concurrently-presented stimuli. Shortening cue duration would also test the competing hypotheses for the delayed orienting performance of old-old adults in Experiment 1. If old-old adults had difficulty processing the gaze cue, then their validity effects should be further diminished or delayed with a shorter cue duration. However, if old-old adults had difficulty disengaging from a persistent cue, then reducing cue duration should encourage disengagement, leading to validity effects at the early cue-target interval.

Method

Participants

Forty young adults (18-28 yrs; 27 women, 13 men), 40 young-old adults (60-74 yrs; 27 women, 13 men), and 40 old-old adults (75-91 yrs; 27 women, 13 men) were included in the data analysis for Experiment 2 (see Table 1 for participants’ screening and psychometric data). Participants were recruited and screened in the same manner as Experiment 1, but there were no participants in common across the two experiments.

Materials and procedure

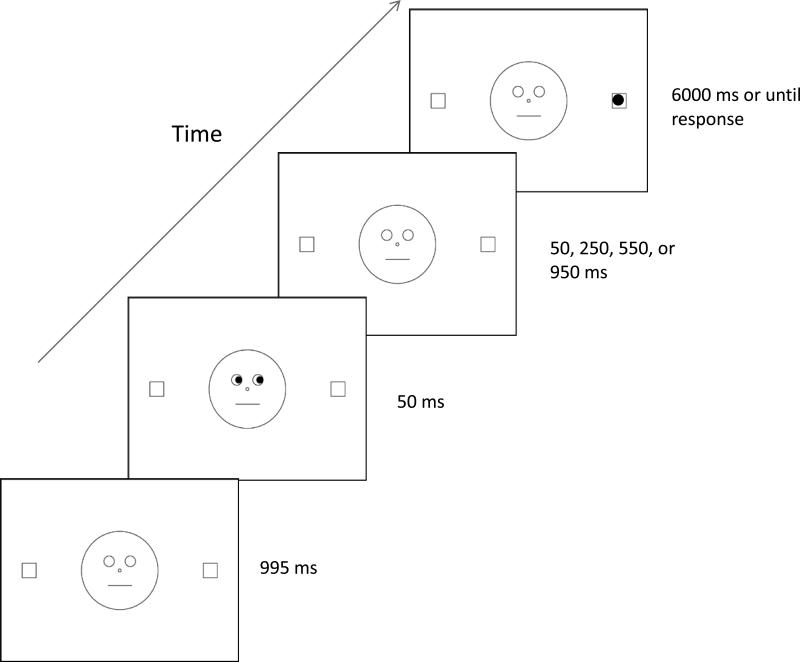

The materials, stimuli, and procedure were the same as those described in Experiment 1, except that the cue no longer overlapped temporally with the target, but was instead presented for 50 ms and then removed and replaced by the initial fixation display. A sample trial sequence is presented in Figure 3. After an inter-stimulus interval of 50, 250, 550, or 950 ms (corresponding to cue-target SOAs of 100, 300, 600, and 1,000 ms), the target was presented until the participant responded or 6,000 ms had elapsed. As in Experiment 1, participants were told that the gaze direction would not assist them in predicting the target location. Participants completed two blocks of 80 trials, for a total of 160 experimental trials (80 valid and 80 invalid). Each block began with eight practice trials.

Figure 3.

Trial sequence for Experiment 2. The stimuli are not drawn to scale.

Results

Mean RTs as a function of age group, cue validity, and cue-target SOA are presented in Table 3. Errors were rare within each condition for each age group (less than 2%). Outlier RTs (less than 150 ms or more than 2,500 ms; less than 1% of trials per group) were removed, and median RTs were calculated for correct responses and submitted to the same 3 × 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA described in Experiment 1.

Table 3.

Response Times (ms) as a Function of Age Group, Cue Validity, and SOA (ms) for Experiment 2.

| Young Adults |

Young-Old Adults |

Old-Old Adults |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOA |

V |

I |

I-V

|

V |

I |

I-V

|

V |

I |

I-V

|

| RT means | |||||||||

| 100 | 356 | 371 | 15 * | 461 | 475 | 14 * | 503 | 519 | 16 * |

| 300 | 314 | 326 | 12 * | 424 | 434 | 10 * | 467 | 484 | 17 * |

| 600 | 308 | 310 | 2 | 404 | 409 | 5 | 450 | 453 | 3 |

| 1000 | 304 | 307 | 3 | 398 | 401 | 3 | 447 | 452 | 5 |

| RT SDs | |||||||||

| 100 | 51 | 47 | 20 | 72 | 75 | 23 | 91 | 99 | 27 |

| 300 | 47 | 52 | 19 | 66 | 67 | 29 | 86 | 94 | 24 |

| 600 | 45 | 43 | 19 | 69 | 69 | 26 | 88 | 94 | 26 |

| 1000 | 44 | 42 | 16 | 67 | 64 | 31 | 94 | 97 | 31 |

Note. RT = response time, SOA = stimulus onset asynchrony between the gaze cue and target, V = validly-cued target, I = invalidly-cued target, I-V = Invalid RT minus Valid RT (mean difference score).

the difference score was significantly greater than 0 by t test, p < .05.

†the difference score was marginally greater than 0 by t test, .05 <p < 10.

All main effects were significant: age group, F(2, 117) = 48.25, p < .001, cue validity, F(1, 117) = 50.75, p < .001, and cue-target SOA, F(3, 351) = 214.21, p < .001. Old-old adults were slower to respond than young-old adults, who were in turn slower to respond than young adults (472, 426, and 325 ms, respectively), as indicated by SNK post hoc tests, ps < .05. There was a significant validity effect; participants responded more quickly to validly-cued targets (403 ms) than to invalidly-cued targets (412 ms). The main effect of cue-target SOA once again reflected an overall decrease in RT as SOA increased (448, 408, 389, and 385 ms for SOAs of 100, 300, 600, and 1,000 ms, respectively).

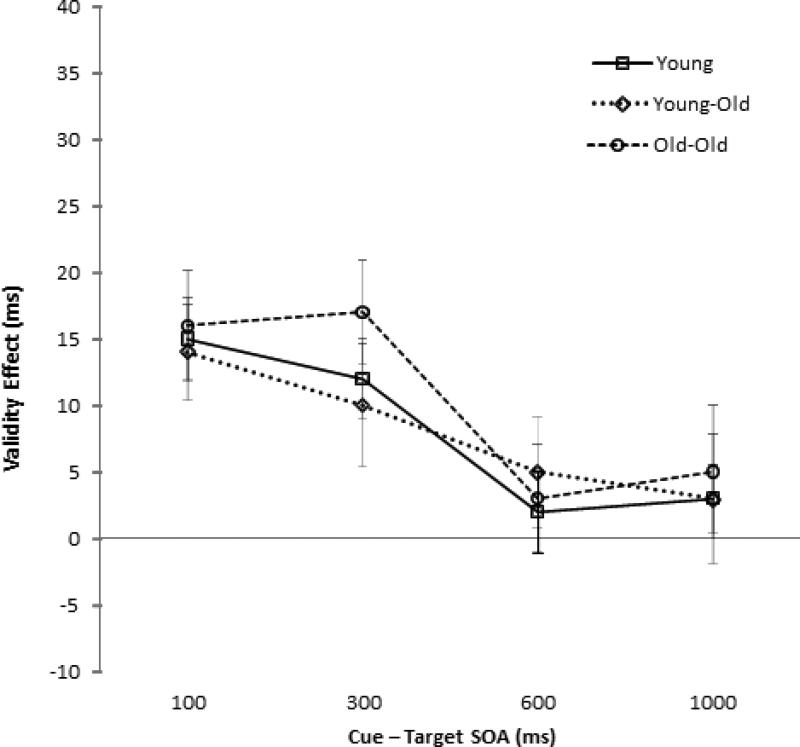

There was a Cue Validity × SOA interaction, F(3, 351) = 7.43, p < .001, which we examined with separate one-way ANOVAs on cue validity at each SOA. Validity effects were significant at the 100 ms, F(1, 119) = 49.65, p < .001, and 300 ms SOAs, F(1, 119) = 32.81, p < .001 (15 ms and 13 ms, respectively), but not at the 600 ms, F(1, 119) = 2.36, p = .127, or 1,000 ms SOAs, F(1, 119) = 2.11, p = .149 (3 ms and 4 ms, respectively). The Age Group × Cue Validity × SOA interaction was not significant, F(6, 351) = 0.21, p = .975. Significant age differences in the validity effect difference scores (invalid RT minus valid RT) were not found at any of the SOAs, all Fs < 1 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cueing effects (invalid response times [RTs] minus valid RTs) for each age group across the four stimulus onset asynchronies (SOAs) for Experiment 2.

Using the approach described in Experiment 1, we transformed the data to address the potential influence of general slowing on validity effects (in this case, determining whether slowing masked age-related decreases in validity effects). After the Brinley transform on young adult and young-old adult data (using Equations 3 and 4 below), we repeated the 3 × 2 × 4 ANOVA. As expected, age differences in reaction time were no longer observed (mean RTs of 473, 470, and 472 ms for young adults, young-old adults, and old-old adults, respectively), F(2, 117) = 0.02, p = .983. The main effects of cue validity, F(1, 117) = 51.69, p < .001, and SOA, F(3, 351) = 217.91, p < .001, remained significant, as did the two-way interaction between cue validity and SOA, F(3, 351) = 7.71, p < .001. Significant age differences in validity effects were not found at any of the SOAs, all Fs < 1.10, all ps > .30.

| (3) |

| (4) |

Discussion

In Experiment 2, even with a short-duration gaze cue that was removed prior to target onset, cueing effects developed quickly. Responses were faster to targets at gazed-at locations than to targets at opposite locations, and these validity effects were evident at cue-target SOAs of 100 and 300 ms. As found in Experiment 1, validity effects diminished at longer cue-target intervals. The response pattern was largely unchanged from Experiment 1 and was consistent with the reflexive orienting pattern observed in other gaze cue studies using a longer-duration cue (e.g., Bayliss, di Pelligrino, & Tipper, 2005; Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Ristic et al., 2002). The performance of all three age groups in Experiment 2 reflected reflexive orienting in response to gaze cues, and the magnitude of the orienting effect did not vary by age. As such, it is difficult to argue that the validity effects of Experiment 1 were due primarily to competition between incompatible stimuli.

We did not find significant age differences in orienting patterns. The results of Experiment 2 were most consistent with the interpretation that, in Experiment 1, old-old adults were not able to disengage rapidly from the gaze cue while it remained on the screen. It appeared that shortening the duration of the cue in Experiment 2 encouraged such disengagement, and thus, validity effects emerged at 100 ms. Furthermore, the results were not consistent with our alternative hypothesis that in Experiment 1 old-old adults were slow to demonstrate validity effects because of diminished processing of the cue. If this had been the case, we would have expected further degradation of orienting effects with the shortened cue duration of 50 ms.

General Discussion

Faces and eyes provide important social information. Following a person's gaze allows individuals to rapidly share information about items or events of interest in the visual environment. The present findings provide additional evidence that gaze shifting triggers reflexive orienting (Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Frischen et al., 2007). Participants were faster to detect a target when its location had been indicated by a gaze shift, even when gaze direction was not predictive across trials of target location. The validity effects developed rapidly, by 100 and 300 ms after cue onset, and diminished at longer cue-target intervals, which was consistent with the time course of reflexive rather than volitional orienting (Jonides, 1981; Klein et al., 1992). Even when the cue was removed prior to target onset (Experiment 2), validity effects remained, arguing against conflict between concurrently presented stimuli as the reason responses were slower to invalidly-cued targets (Green et al., 2013; Green & Woldorff, 2012).

Older adults’ response patterns also supported a reflexive orienting interpretation. Their validity effects were comparable in magnitude and time course to those of young adults, developing quickly and resolving over time. One age-related difference was noted for old-old adults, who showed delayed validity effects with long-duration cues. Shortening the cue duration hastened the onset of the validity effect, a finding that is inconsistent with a cue-target conflict interpretation. If validity effects represent interference from conflicting stimulus input, then it is difficult to imagine how shortening the cue duration would increase the early-SOA interference effect for old-old adults. Instead, the findings suggest that old-old adults were slow to disengage from a persistent gaze cue (the face itself, presented at central fixation) but could orient toward the gazed-at location once the cue was removed. Overall, the response pattern (rapid development of validity effects that diminished at longer cue-target intervals) produced under the present stimulus conditions (in response to uninformative, central cues that did not overlap temporally with the target) and across multiple age groups (young adults, young-old adults, and old-old adults) argues for an interpretation of reflexive orienting in response to central directional gaze cues that is relatively unchanged with age.

Although smaller in magnitude than the validity effects at 100 and 300 ms, validity effects in Experiment 1 (with long duration cues) were significant at 600 and 1,000 ms. Validity effects were not significant at the longer SOAs in Experiment 2 (with short duration cues). A similar pattern of validity effects has been found for young adults in other gaze cueing studies using long duration cues, with significant but small (e.g., 5-10 ms) validity effects at SOAs of 500 ms or longer (Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Hietanen, Leppänen, Nummenmaa, & Astikainen, 2008; Nummenmaa & Hietanen, 2009; Ristic et al., 2002). Like our results from Experiment 2, Greene and colleagues (2009) did not find validity effects at 900 ms with short duration cues. Interestingly, McKee and colleagues (2007) used long and short duration cues (the short duration cues involved the eye gaze returning to center) within the same experiment and found validity effects were larger for long duration cues than short duration cues at 720 and 1440 ms. Together the evidence suggests that gaze cue duration is an important predictor of the time course of cueing effects, and that participants are better able to maintain attention at a gazed-at location when the cue remains present. Whether extended validity effects for long duration cues are the result of voluntary or reflexive attention requires further investigation.

Importantly, we found evidence for reflexive orienting in response to central gaze cues in both young and older adults, indicating that this socially-relevant cue remains an influential attentional trigger later in life. Although older adults demonstrated gaze-induced orienting in earlier studies (Slessor et al., 2008, 2010), there was an age-related decrease in cueing effects that was likely due to enhanced validity effects for young adults associated with the use of young adult face cues (age-consistency effects; Slessor et al., 2010). The present study used a schematic face rather than a photographed face to avoid age-consistency effects, and we did not observe age-related decreases in validity effects. Instead, the magnitude and time course of older adults’ gaze-triggered validity effects were indistinguishable from those of young adults, at least when cue duration was short. We also demonstrated in the present study, using uninformative cues and short cue-target intervals, the reflexive nature of older adults’ gaze-triggered orienting, whereas earlier studies investigated age patterns under conditions that allowed the possibility of volitional orienting (predictive cues or long cue-target intervals; Slessor et al., 2008, 2010).

Given the social significance and ubiquitous nature of gaze cues in daily interpersonal interactions, perhaps it is not surprising to find that older adults oriented in response to gaze shifts. However, with continuing debate regarding the reflexive nature of central directional cues (Chanon & Hopfinger, 2011; Green et al., 2013; Green & Woldorff, 2012; Stevens, West, Al-Aidroos, Weger, & Pratt, 2008), and with unique age patterns for different forms of directional cues (central or peripheral, volitional or reflexive; Castel, Chasteen, Scialfa, & Pratt, 2003; Folk & Hoyer, 1992; Langley et al., 2011; Lincourt et al., 1997), it is important to establish the orienting response of older adults to this uniquely social cue. Moreover, the age-related stability of gaze-triggered orienting likely has important implications for joint attention in older adults. With evidence that age is associated with reductions in attentional capacity (Craik, Luo, & Sakuta, 2010; Kim & Giovanello, 2011; Tellinghuisen et al., 1996), reflexive gaze-triggered orienting, which puts little demand on processing resources (Xu, Zhang, & Geng, 2011), could be important for helping older adults efficiently process the attentional viewpoint of others. Gaze-triggered orienting likely continues to be important for learning and social interactions in later life.

In many ways, the patterns observed in the present study are similar to the age-related patterns established with uninformative central arrow cues (Langley et al., 2011). In a paradigm identical to the present one except for the cueing stimuli, arrow-triggered validity effects developed quickly (by 100 ms for all three age groups) and lasted longer for older adults (still observed at 300 ms; Experiment 1). This age difference was minimized when the cue was removed prior to target onset (Experiment 2). In the present study, orienting effects were also established quickly (by 100 ms), except for old-old adults who did not show validity effects until 300 ms. Thus, both studies showed early validity effects (at 100 and 300 ms) that diminished at later cue-target intervals, consistent with reflexive orienting to central cues for all age groups. Also, in both studies, orienting responses to central cues were at least as strong in older adults as in young adults. Although the results were obtained in separate studies, the similarity in age patterns for arrow and gaze cues joins other evidence suggesting that the orienting processes for these two types of central cues share important commonalities (Bayliss et al., 2005; Ristic et al., 2002; Stevens et al., 2008). In fact, Ristic and Kingstone (2012) recently proposed that there exists a unique orienting system for central symbolic cues (like arrows and eye direction) that provide behaviorally and biologically relevant directional information. This “automated symbolic orienting system,” as they labeled it, responds to central symbolic cues in a rapid, unintentional, and automatic (reflexive) fashion. In contrast to exogenous orienting to peripheral onset events, the reflexive nature of orienting induced by central symbolic cues results from repeated exposure to strong environmental contingencies over time (e.g., arrows consistently provide valid information for guiding spatial navigation). As evidence that the automated symbolic orienting system is distinct from traditionally defined exogenous and endogenous orienting systems, Ristic and Kingstone demonstrated that when central symbolic cues (uninformative arrows) were presented with classic cues known to engage either the exogenous orienting system (uninformative peripheral onset cues) or the endogenous orienting system (directionally-predictive central digits), the effects of the two types of cues were independent (did not interact). Thus, the reflexive orienting patterns in response to uninformative central cues that were observed in the current study are consistent with the automated symbolic orienting system proposed by Ristic and Kingstone.

The primary age-related difference in orienting patterns between gaze and arrow cues was specific to old-old adults. Individuals over 75 years were slow to orient in response to a persistent gaze cue (with no orienting effects until 300 ms), but in a previous study using a nearly identical paradigm (Langley et al., 2011), old-old adults were not slow to orient in response to a persistent arrow cue. Because of the important social information that faces and eyes convey, there may be an innate or learned tendency to focus on faces when present (e.g., maintaining eye contact during social interactions; Kingstone et al., 2003). Old-old adults, who are known to have difficulty disengaging from other types of cues (Greenwood et al., 1993; Langley et al., 2011), may have maintained focus on the gaze cue longer than the other age groups when it remained present (Experiment 1). Slow disengagement from the cue face would have delayed attention to the location indicated by the cue (thus, no cueing effects at 100 ms). We found evidence to support the disengagement hypothesis in Experiment 2; old-old adults showed rapid validity effects when the gaze cue was removed prior to target presentation. Together, the results suggest that gaze cues reflexively orient attention, but that late in life, a reduced ability to withdraw from socially-relevant information, particularly when that information is salient or persisting, may alter or compete with orienting processes. The results also suggest that disengagement difficulties may manifest themselves differently with different types of cues. In past studies, old-old adults demonstrated enhanced cueing effects with arrow and peripheral cues (Greenwood et al., 1993, 1994; Langley et al., 2011). This pattern suggests that rather than being slow to disengage from the cue itself (at least in the case of arrow cues), that old-old adults quickly directed attention toward the cued location, but that they were then slow to disengage from the cued location, which served to enhance the cueing effect when the target then appeared.

It should be noted that, although we used an age of 75 years to distinguish the young-old group from the old-old group, it is likely that changes in attentional disengagement occur progressively in late life rather than abruptly after a certain age. We should also keep in mind, when considering the age patterns from the present study, that we tested two high functioning groups of older adults (with more years of education and higher vocabulary scores than the young adult group); thus our findings may not represent age differences in spatial orienting that would be found in a more general population of older adults.

In the present study, we did not include a neutral condition (e.g., a cue with pupils directed straight ahead) to distinguish the benefits of a valid cue from the costs of an invalid cue. Ideally, benefits (faster responses to validly-cued targets than to neutrally-cued targets) reflect shifts of attention initiated by a valid cue, whereas costs (slower responses to invalidly-cued targets than to neutrally-cued targets) reflect the time needed to reorient attention from the gazed-at location to the location of the target. Both benefits and costs should be evident to support a spatial orienting interpretation. If performance is characterized by only costs (Green et al., 2013; Green & Woldorff, 2012, Experiment 2), then it is difficult to argue that a gaze shift facilitated orienting to a location. That said, it can be challenging to establish a truly neutral condition with which to assess benefits and costs (Jonides & Mack, 1984), and as a result, most studies have examined orienting patterns in the absence of neutral cues (e.g., Bayliss et al., 2005; Quadflieg, Mason, & Macrae, 2004; Tipples, 2002). A notable exception is one of the initial gaze-cueing studies (Friesen & Kingstone, 1998), which found that validity effects were due primarily to benefits rather than costs. This pattern was established with long-duration cues and should be re-addressed with short-duration cues, and in the performance of both young and older adults.

Another consideration with regard to the paradigm was the opportunity for response bias to influence validity effects. Participants made a target localization response (indicating whether the target was to the left or right of fixation) by pressing left and right buttons. The directional gaze cue (looking left or right) may have primed a particular response rather than oriented attention to a particular location. However, there is evidence that argues against a response priming interpretation. Friesen and Kingstone (1998) examined young adults’ validity effects to gaze cues using three responses: target localization, letter discrimination, and target detection. Because the latter two responses did not rely on target location, cueing effects could not be influenced by response bias. Validity effects did not differ in magnitude between the three response types, reducing the possibility that response priming influenced validity effects on the localization task. Also arguing against a response bias interpretation is the validity effect pattern for old-old adults in the present study. In Experiment 1, old-old adults were slower to show validity effects than the two younger groups. From a response bias perspective, we would interpret this delay as an age-related slowing in priming development. However, when the gaze cue was removed prior to target presentation in Experiment 2, old-old adults showed validity effects at the shortest SOA. If the gaze cue was priming a particular response, why would priming be facilitated with a shorter duration cue? Although we argue in favor of an attention-based interpretation of the present findings, we acknowledge that response bias could have influenced the results. It would be diligent to replicate the present findings with responses (e.g., target detection, feature discrimination) that reduce to opportunity for response bias.

Also worth investigating is whether the three age groups would produce similar validity effects using a simultaneous cue-target condition (0 ms SOA). Green and Woldorff (2012) argued that cueing effects for simultaneous stimuli likely represent cue-target conflict rather than orienting. However, because the cue is presented at visual fixation, it is possible that the cue is processed before the target and thus still serves to direct attention to the target, even when presented simultaneously with the target. As a consequence, this cueing condition may not be a strong discriminator between stimulus conflict and orienting effects. That said, for cueing effects in the simultaneous condition to be interpreted as attentional orienting, they should be consistent with the time course of cueing effects across the other cue-target SOAs (e.g., showing strong cueing effects at the 0 ms SOA or a buildup of cueing effects with increasing SOA, depending on the age group and cue duration).

To conclude, we found that all three age groups oriented rapidly in response to a shift in gaze when gaze direction was not predictive of target location. Orienting effects diminished quickly, consistent with reflexive responses to central directional cues. The response pattern could not be accounted for by stimulus conflict between an incongruent cue and target because orienting effects were maintained when the cue and target were separated in time. Age effects were minimal, suggesting relative preservation of this orienting system later in life, which could have important implications for the stability of joint attention. Observed age effects were specific to individuals over age 75, such that old-old adults took longer to orient attention to a gazed-at location when the gaze cue remained present, suggesting that this group was slow to disengage attention from the cue. Thus, although this form of orienting behavior appears to be relatively stable with age, under certain conditions it has the potential for subtle modification in late life.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jaryn Allen, Lindsay Anderson, Amanda Benz, Erin Beske, Megan Busch, Joseph Gabel, Heather Joyce, Laura Klubben, Savannah Kraft, RaeAnn Levang, Veselin Marinov, Alexandra McCroskey, Shanna Morlock, Sarah Nelson, Tanya Peterson, Katherine Sage, Carrie Spillers, Melissa Tarasenko, Sabrina Thompson, Nicole Kiewel, Heather Wadeson, and Ericka Wentz for their assistance collecting the data.

Funding

This work was supported by grant NIH P20 GM10305 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), a component of the National Institute of Health (NIH). The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the NIH or NIGMS.

References

- Bayliss AP, di Pelligrino G, Tipper SP. Sex differences in eye gaze and symbolic cueing of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2005;58A:631–650. doi: 10.1080/02724980443000124. doi:10.1080/02724980443000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Chasteen AL, Scialfa CT, Pratt J. Adult age differences in the time course of inhibition of return. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2003;58B:256–259. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.5.p256. doi:10.1093/geronb/58.5.P256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerella J. Generalized slowing in Brinley plots. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1994;49B:65–71. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.p65. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.P65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanon VW, Hopfinger JB. ERPs reveal similar effects of social gaze orienting and voluntary attention, and distinguish each from reflexive attention. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2011;73:2502–2513. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0209-4. doi:10.3758/s13414-011-0209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KJ, Moye J, Armson RR, Kern TM. Health screening and random recruitment for cognitive aging research. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:204–208. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.2.204. doi:10.1037//0882-7974.7.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik FIM, Luo L, Sakuta Y. Effects of aging and divided attention on memory for items and their contexts. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:968–979. doi: 10.1037/a0020276. doi: 10.1037/a0020276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver J, Davis G, Ricciardelli P, Kidd P, Maxwell E, Baron-Cohen S. Gaze perception triggers reflexive visuospatial orienting. Visual Cognition. 1999;6:509–540. doi: 10.1080/135062899394920. [Google Scholar]

- Faust ME, Balota DA, Spieler DH, Ferraro FR. Individual differences in information-processing rate and amount: Implications for group differences in response latency. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:777–799. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.777. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.125.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folk CL, Hoyer WJ. Aging and shifts of visual spatial attention. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:453–465. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.453. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of the patient for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen CK, Kingstone A. The eyes have it! Reflexive orienting is triggered by nonpredictive gaze. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 1998;5:490–495. doi:10.3758/ BF03208827. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen CK, Kingstone A. Covert and overt orienting to gaze direction cues and the effects of fixation offset. NeuroReport. 2003;14:489–493. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200303030-00039. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200303030-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen CK, Moore C, Kingstone A. Does gaze direction really trigger a reflexive shift of spatial attention? Brain and Cognition. 2005;57:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.08.025. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen CK, Ristic J, Kingstone A. Attentional effects of counterpredictive gaze and arrow cues. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2004;30:319–329. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.30.2.319. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.30.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischen A, Bayliss AP, Tipper SP. Gaze cueing of attention: Visual attention, social cognition, and individual differences. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:694–724. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.694. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JJ, Gamble ML, Woldorff MG. Resolving conflicting views: Gaze and arrow cues do not trigger rapid reflexive shifts of attention. Visual Cognition. 2013;21:61–71. doi: 10.1080/13506285.2013.775209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JJ, Woldorff MG. Arrow-elicited cueing effects at short intervals: Rapid attentional orienting or cue-target stimulus conflict? Cognition. 2012;122:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.08.018. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene DJ, Mooshagian E, Kaplan JT, Zaidel E, Iacoboni M. The neural correlates of social attention: Automatic orienting to social and nonsocial cues. Psychological Research. 2009;73:499–511. doi: 10.1007/s00426-009-0233-3. doi: 10.1007/s00426-009-0233-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood PM, Parasuraman R. Attentional disengagement deficit in nondemented elderly over 75 years of age. Aging and Cognition. 1994;1:188–202. doi: 10.1080/13825589408256576. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood PM, Parasuraman R, Haxby JV. Changes in visuospatial attention over the adult lifespan. Neuropsychologica. 1993;31:471–485. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(93)90061-4. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(93)90061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley AA, Kieley JM, Slabach EH. Age difference and similarities in the effects of cues and prompts. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1990;16:523–537. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.16.3.523. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.16.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietanen JK, Leppänen JM, Nummenmaa L, Astikainen P. Visuospatial attention shifts by gaze and arrow cues: An ERP study. Brain Research. 2008;1215:123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.091. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B, Pratt J, Colzato L, Godijn R. Symbolic control of visual attention. Psychological Science. 2001;12:360–365. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00367. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J. Voluntary versus automatic control over the mind's eye's movement. In: Long J, Baddeley A, editors. Attention and performance IX. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Mack R. On the cost and benefit of cost and benefit. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;96:29–44. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.96.1.29. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Giovanello KS. The effects of attention on age-related relational memory deficits: Evidence from a novel attentional manipulation. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:678–688. doi: 10.1037/a0022326. doi: 10.1037/a0022326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingstone A, Smilek D, Ristic J, Friesen CK, Eastwood JD. Attention, researchers! It is time to take a look at the real world. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:176–180. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01255. [Google Scholar]

- Kingstone A, Tipper C, Ristic J, Ngan E. The eyes have it! An fMRI investigation. Brain and Cognition. 2004;55:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.02.037. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RM, Kingstone A, Pontefract A. Orienting of visual attention. In: Rayner K, editor. Eye movements and visual cognition: Scene perception and reading. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 1992. pp. 46–63. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-2852-3_4. [Google Scholar]

- Langley LK, Friesen CK, Saville AL, Ciernia AT. Timing of reflexive visuospatial orienting in young, young-old, and old-old adults. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2011;73:1546–1561. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0108-8. doi:10.3758/s13414-011-0108-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincourt AE, Folk CL, Hoyer WJ. Effects of aging on voluntary and involuntary shifts of attention. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 1997;4:290–303. doi: 10.1080/13825589708256654. doi:10.1080/13825589708256654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DJ, Whiting WL, Cabeza R, Huettel SA. Age-related preservation of top-down attentional guidance during visual search. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:304–309. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.304. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee D, Christie J, Klein R. On the uniqueness of attentional capture by uninformative gaze cues: Facilitation interacts with the Simon effect and is rarely followed by IOR. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2007;61:293–303. doi: 10.1037/cjep2007029. doi: 10.1037/cjep2007029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P, Newell L. Attention, joint attention, and social cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00518.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nummenmaa L, Hietanen JK. How attentional systems process conflicting cues: The superiority of social over symbolic orienting revisited. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2009;35:1738–1754. doi: 10.1037/a0016472. doi: 10.1037/a0016472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI. Chronometric explorations of mind. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1980;32:3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. doi:10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Cohen YA. Components of visual orienting. In: Bouma H, Bouwhuis DG, editors. Attention and performance X. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. pp. 531–554. [Google Scholar]

- Quadflieg S, Mason MF, Macrae CN. The owl and the pussycat: Gaze cues and visuospatial orienting. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2004;11:826–831. doi: 10.3758/bf03196708. doi:10.3758/BF03196708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristic J, Friesen CK, Kingstone A. Are eyes special? It depends on how you look at it. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2002;9:507–513. doi: 10.3758/bf03196306. doi:10.3758/BF03196306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristic J, Kingstone A. Taking control of reflexive social attention. Cognition. 2005;94:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristic J, Kingstone A. A new form of human spatial orienting: Automated symbolic orienting. Visual Cognition. 2012;20:244–264. doi: 10.1080/13506285.2012.658101. [Google Scholar]

- Ristic J, Wright A, Kingstone A. Attentional control and reflexive orienting to gaze and arrow cues. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2007;14(5):964–969. doi: 10.3758/bf03194129. doi:10.3758/BF03194129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slessor G, Laird G, Phillips LH, Bull R, Filippou D. Age-related differences in gaze following: Does the age of the face matter? Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2010;65B:536–541. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq038. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slessor G, Phillips LH, Bull R. Age-related declines in basic social perception: Evidence from tasks assessing eye-gaze processing. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:812–822. doi: 10.1037/a0014348. doi:10.1037/a0014348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens SA, West GL, Al-Aidroos N, Weger UW, Pratt J. Testing whether gaze cues and arrow cues produce reflexive or volitional shifts of attention. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2008;15:1148–1153. doi: 10.3758/PBR.15.6.1148. doi:10.3758/PBR.15.6.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellinghuisen DJ, Zimba LD, Robin DA. Endogenous visuospatial precuing effects as a function of age and task demands. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 1996;58:947–958. doi: 10.3758/bf03205496. doi: 10.3758/BF03205496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipples J. Eye gaze is not unique: Automatic orienting in response to uninformative arrows. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2002;9:314–318. doi: 10.3758/bf03196287. doi:10.3758/BF03196287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Zhang S, Geng H. Gaze-induced joint attention persists under high perceptual load and does not depend on awareness. Vision Research. 2011;51:2048–2056. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2011.07.023. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]