Abstract

AIM: To study the salient features of colorectal cancer (CRC) in Libya.

METHODS: Patients records were gathered at the primary oncology clinic in eastern Libya for the period of one calendar year (2012). Using this data, various parameters were analyzed and age-standardized incidence rates were determined using the direct method and the standard population.

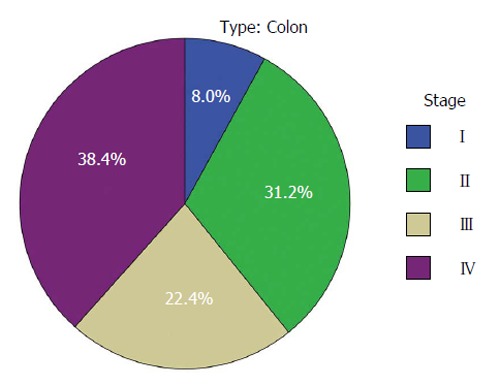

RESULTS: During 2012, 174 patients were diagnosed with CRC, 51.7% (n = 90) male and 48.3% (n = 84) females. The average age was 58.7 (± 13.4) years, with men around 57.3 (± 13) years old and women usually 60.1 (± 13.8) years of age. Libya has the highest rate of CRC in North Africa, with an incidence closer to the European figures. The age-standardized rate for CRC was 17.5 and 17.2/100000 for males and females respectively. It was the second most common cancer, forming 19% of malignancies, with fluctuation in ranking and incidence in different cities/villages. Increasingly, younger ages are being afflicted and a higher proportion of patients are among the > 40 years subset. Nearly two-thirds presented at either stage III (22.4%) or IV (38.4%).

CONCLUSION: Cancer surveillance systems should be established in order to effectively monitor the situation. Likewise, screening programs are invaluable in the Libyan scenario given the predominance of sporadic cases.

Keywords: Colorectal carcinoma; Cancer incidence; Age-standardized rates; Benghazi, Libya; North Africa; Young age; Urban-rural differences

Core tip: Colorectal cancer incidence in Libya has changed greatly since the last time it was determined nearly a decade ago. Libya was found to have the highest incidence rate in North Africa, with younger ages more affected. Late presentation was found to be a major problem in the Libyan case. Clear urban-rural differences were seen when the different districts were analyzed. Different hypotheses are put forth to explain these variations. Proper surveillance and screening programs need to be established and healthcare policies should be adjusted to take into account the increasing rate of this malignancy.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide[1,2], with the disease incidence rising with advanced age[3,4]. The overall mortality from CRC is 60%, which represents the second leading cause of cancer death in western societies. Figures on incidence from Libyan sources are over a decade old and have multiple limitations[5]. Unfortunately, there has not been a major improvement in patient survival despite the advances made in our understanding of disease and in chemotherapy practice[6]. Surgical cure of CRC is determined by stage of the tumor and its biological behavior. Early CRCs can be cured with surgery alone.

Even today, most CRC patients undergo potentially curative surgery and receive adjuvant chemotherapy but approximately 50% of the patients initially thought to be cured subsequently relapse and die of their disease[7]. Advanced CRC is defined as a disease that is either metastatic or locally advanced and in which surgical resection is unlikely to be curative[8]. Once metastasis has occurred, the patient’s prognosis is considerably worse, with the 5-year survival rate being < 5%[8]. For the majority of patients, chemotherapy can yield improvements in survival and is the main modality of treatment in these patients[9].

CRC was found to be the leading malignancy in Libyan males and the second most prevalent among females[10]. On a global scale, it is the third most common form of cancer[11].

On the whole, the incidence of colorectal carcinoma in Middle Eastern countries is lower than that of Western countries[12]. The North African countries have consistently contributed their registry data to scientific literature[13-18]. Due to a number of difficulties, very limited data exists for Libya[10,19,20]. Moreover, epidemiological features of CRC have never been studied, despite being a major form of malignancy. A unique research opportunity is offered in the Libyan scenario where the traditional lifestyle still prevails in rural areas and the urban (Westernized) mode of living dominates in the cities.

Using data that was actively collected from the Department of Oncology at the Benghazi Medical Center, the primary oncology center in eastern Libya, the salient features of colorectal carcinoma patients were analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Libya is a North African country categorized under the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office in the WHO classification. According to the 2006 census, over 5.5 million people lived in Libya, with 28.5% (n = 1613749) residing in the eastern part of the country. Benghazi is the largest city in eastern Libya, with over 670000 inhabitants. The catchment area includes eight major locations comprising urban, suburban and rural populations (Figure 1) and patients were classified under these main districts according to proximity.

Figure 1.

Map of Libya highlighting the districts that were studied and included in the eastern Libya cancer pool.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee at the Libyan International Medical University. All personal identifiers were stripped from the data and only medically significant data was analyzed.

Data collection

Data was obtained from the patient records at the Department of Oncology in the Benghazi Medical Center who were diagnosed from the period of January 1st to December 31st, 2012. In Libya, an ineffective primary health system forces the populace to deal directly with outpatient departments in secondary and tertiary centers. This is true for Libyan oncology patients where they all present to the oncological outpatient department after a referral from another specialty. They are then diagnosed and given a treatment plan. The department effectively receives all the cancer cases in Benghazi and the overwhelming majority of the cases in eastern Libya (being the only oncological center in the region). The patients were diagnosed through various techniques, particularly microscopic verification and clinically/radiologically diagnosis. However, due to clerical difficulties, this parameter (i.e., the method of diagnosis) could not reliably be collected for all patients and hence was excluded from the analysis. This data serves as a good indicator for eastern Libya in general and Benghazi in particular.

Hematological malignancies were not included in this study since such patients are recorded at the Department of Hematology and their data was not made available.

Different parameters were recorded for each patient: age, gender, city, type of cancer, subtype and staging. In the light of clerical errors, a number of cases were set aside for a certain parameter but used for others. The patients were filtered by city of origin to include only patients residing in the eastern part and not referrals.

Statistical analysis

The data was computerized in a data sheet and organized as per International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O). An SPSS-based model was designed that spanned the collected data and basic statistical procedures were performed (t tests and χ2 tests).

The 2012 Libyan population was determined using the 2006 Libyan census, taking into consideration the appropriate population growth. Age-specific incidence and age-standardized rates (ASRs) were calculated via the direct method using the standard population distribution[15] arranged by site (ICD-O).

RESULTS

During 2012, a total of 174 patients were diagnosed with colorectal carcinoma in the eastern region of Libya. Slightly over half of the cases (51.7%, n = 90) were male, while 48.3% (n = 84) were females. The average overall age of the patients was 58.7 (± 13.4) years, with men around 57.3 (± 13) years old and women usually 60.1 (± 13.8) years of age. The ASR for CRC was 17.5 and 17.2/100000 for males and females respectively. It was the second most common cancer overall in the eastern region, forming 19% of all malignancies, with fluctuation in ranking in different towns/villages.

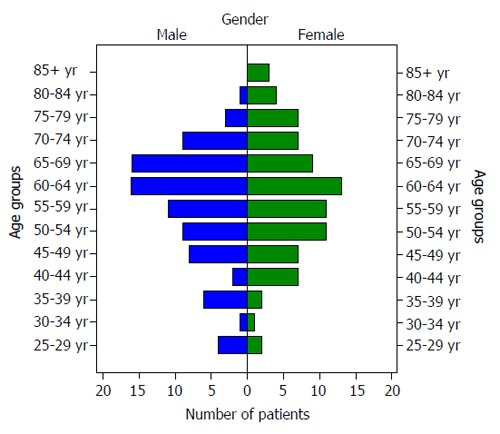

When the age was categorized into groups, it was found that a peak occurred in the 60-64 year age group (17.1%, n = 29), which was true for both genders. Nearly one tenth of colorectal carcinoma patients (9.4%, n = 16) were diagnosed < 40 years. Males were more than two-thirds (68.8%, n = 11) of these patients, giving a male to female ratio of 2.2. One quarter of CRC patients (23.5%, n = 40) presented before the age of 50 years and that figure jumped to over one-third of patients when cases under 55 years are studied (35.3%, n = 60). Figure 2 depicts the distribution of CRC by age and gender.

Figure 2.

Population pyramid of the colorectal cancer patients split by gender.

The three areas that contributed the greatest number of colon cancer cases were Benghazi (64.9%, n = 113), Al-Beida (9.8%, n = 17) and Al-Marj (8%, n = 14). When looking at population distribution from the Libyan 2006 census, one clearly observes that the city of Benghazi is over-represented, while the other (more rural) areas were starkly under-represented. Nearly two-thirds of colon cancer patients were from Benghazi, whereas its inhabitants constitute only 41% of the population in eastern Libya (χ2 = 41.291, P < 0.001). A small proportion (1.7%, n = 3) of the colon cancer patients were foreign nationals. The detailed classification and distribution of these parameters can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Display of key parameters of the cancer patients in eastern Libya

| Overall | Male | Female | ||||

| Age (n/SD) | 58.7 | 13.4 | 57.3 | 13.0 | 60.1 | 13.8 |

| Age group (n/%) | ||||||

| 20-29 yr | 6 | 3.5 | 4 | 4.7 | 2 | 2.4 |

| 30-39 yr | 10 | 5.9 | 7 | 8.1 | 3 | 3.6 |

| 40-49 yr | 24 | 14.1 | 10 | 11.6 | 14 | 16.6 |

| 50-59 yr | 42 | 24.7 | 20 | 23.3 | 22 | 26.2 |

| 60-69 yr | 54 | 31.8 | 32 | 37.2 | 22 | 26.2 |

| 70-79 yr | 26 | 15.3 | 12 | 14.0 | 14 | 16.6 |

| 80+ yr | 8 | 4.7 | 1 | 1.1 | 7 | 8.4 |

| Total | 170 | 100.0 | 86 | 100.0 | 84 | 100.0 |

| Nationality (n/%) | ||||||

| Libyan | 170 | 98.3 | 89 | 100.0 | 81 | 96.4 |

| Non-Libyan | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.6 |

| Total | 173 | 100.0 | 89 | 100.0 | 84 | 100.0 |

| City of origin (n/%) | ||||||

| Ajdabia | 8 | 4.6 | 6 | 6.7 | 2 | 2.4 |

| Beida | 17 | 9.8 | 9 | 10.0 | 8 | 9.5 |

| Benghazi | 113 | 64.9 | 56 | 62.2 | 57 | 67.9 |

| Derna | 6 | 3.4 | 3 | 3.3 | 3 | 3.6 |

| Kufra | 4 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 4.8 |

| Marj | 14 | 8.0 | 8 | 8.9 | 6 | 7.1 |

| Tobruk | 12 | 6.9 | 8 | 8.9 | 4 | 4.8 |

| Total | 174 | 100.0 | 90 | 100.0 | 84 | 100.0 |

The clinical stage was recorded for 125 patients (71.8%) and 49 were excluded due to clerical errors. The majority of cases (38.4%, n = 48) presented at stage IV with another 28 patients at stage III (22.4%). This is further highlighted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of colorectal cancer patients according to clinical stage at diagnosis.

The cases were classified on the site of the cancer as being either right-sided or left-sided colorectal carcinoma. Cancers of the left colon were more common (78.6%, n = 110) than their right-sided counterparts (21.4%, n = 30). This is shown with other parameters in Table 2. When the specific sites were studied (i.e., sigmoid, rectal, etc.), we found that rectal carcinomas were the most common form (36.4%, n = 52). This can be seen in Table 3.

Table 2.

Distribution of the cases in terms of clinical staging, site of cancer and histopathological grade

| Overall | Male | Female | ||||

| Clinical stage (n/%) | ||||||

| I-A | 3 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 3.4 |

| I-B | 7 | 5.6 | 5 | 7.6 | 2 | 3.4 |

| II-A | 28 | 22.4 | 12 | 18.2 | 16 | 27.1 |

| II-B | 11 | 8.8 | 6 | 9.1 | 5 | 8.5 |

| III-A | 5 | 4.0 | 4 | 6.1 | 1 | 1.7 |

| III-B | 11 | 8.8 | 5 | 7.6 | 6 | 10.2 |

| III-C | 12 | 9.6 | 7 | 10.6 | 5 | 8.5 |

| IV | 48 | 38.4 | 26 | 39.4 | 22 | 37.3 |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 66 | 100.0 | 59 | 100.0 |

| Site of cancer (n/%) | ||||||

| Right side | 30 | 21.4 | 14 | 18.9 | 16 | 24.2 |

| Left side | 110 | 78.6 | 60 | 81.1 | 50 | 75.8 |

| Total | 140 | 100.0 | 74 | 100.0 | 66 | 100.0 |

| Histopathological grade (n/%) | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 29 | 33.3 | 17 | 35.4 | 12 | 30.8 |

| Moderately differentiated | 47 | 54.0 | 27 | 56.3 | 20 | 51.3 |

| Poorly differentiated | 11 | 12.6 | 4 | 8.3 | 7 | 17.9 |

| Total | 87 | 100.0 | 48 | 100.0 | 39 | 100.0 |

Table 3.

The distribution of colorectal carcinoma based on site

| Specific site | n | % |

| Anus | 1 | 0.7 |

| Appendix | 1 | 0.7 |

| Asc. colon | 4 | 2.8 |

| Cecum | 6 | 4.2 |

| Left side | 25 | 17.5 |

| Rectum | 52 | 36.4 |

| Right side | 19 | 13.3 |

| Sigmoid | 35 | 24.5 |

| Total | 143 | 100.0 |

Histopathologically, 87 patients (50%) had graded carcinomas. Most were moderately differentiated (54%, n = 47), followed by well differentiated (33.3%, n = 29) carcinomas; poorly differentiated cancers were the least common (12.6%, n = 11). This is further described in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

In terms of incidence, the average rate for Middle Eastern countries was reported as 3/100000-7/100000[21,22]. Even among the North African countries, eastern Libya claims the highest ASR for colon cancer (Table 4)[10,19,23]. While the exact reasons for this inordinately high rate remain to be ascertained, genetic predisposition, increased Westernization of the Libyan diet, physical inactivity and lack of screening programs may be considered important predisposing factors.

Table 4.

Comparison of colorectal cancer incidence rates (age-adjusted per 105)

| Country | Male | Female |

| Benghazi, Libya (2012)[1] | 17.5 | 17.2 |

| Benghazi, Libya (2003)[10] | 11.6 | 8.8 |

| Western Libya[11] | 14.2 | 12.0 |

| Algeria (Setif, 1998-2002)[6] | 6.6 | 6.8 |

| Algeria (Alger, 2006)[7] | 14.8 | 11.0 |

| Egypt (Gharbiah, 1999-2002)[6] | 6.3 | 4.4 |

| Tunisia (Sousse, 1998-2002)[6] | 11.6 | 9.0 |

| Tunisia (Sfax, 2000-2002)[9] | 11.5 | 9.1 |

| Morocco (Rabat, 2005)[4] | 7.2 | 4.6 |

| Morocco (Casablanca, 2004)[5] | 6.6 | 5.7 |

| European Pool (MECC) | 22.0 | 15.6 |

| Iran[15] | 8.2 | 7.0 |

The distribution of colon cancer cases was fairly equal between the genders, despite a conflict in previous literature between reports supporting and others negating a difference between men and women. In terms of age, there was no significant difference between the genders (P = 0.072). The male to female ratio, skewed towards males in the < 40 years subset, was much higher than other nations[24].

Similarly to neighboring Egypt, younger age groups are affected with CRC[25]. One of the principle hypotheses for this trend in that the younger generation live a more Westernized lifestyle (i.e., unhealthy diet with low exercise) and are hence at greater risk[26]. This is of particular importance since the prognosis proportionately worsens below the age of 40 years[27].

Benghazi is the largest city in eastern Libya and the second largest in all of Libya, with a population approaching 800000 inhabitants. Colon cancer was more common in the urban environment in Libya, potentially due to a more sedentary lifestyle, more Westernized diet and a subsequently higher prevalence of obesity. The rural areas in Libya have maintained a relatively traditional way of life with farming, animal rearing and small industries as the main occupations. Traditional cuisine focusing on whole grain and Mediterranean style meals is more common in that environment. While the urban-rural difference has been proven for breast cancer[28], the literature for colon cancer is scanty globally and virtually non-existent for the region.

Foreign nationals are less likely to present to the oncology clinic in Libya as they are more apt to return to their home countries and seek their family upon receiving such news. This would explain their small proportion in the sample.

Over 60% of patients presented at the oncology clinic at advanced stages (III/IV) when the long term prognosis is grim. Around 22.4% (n = 28) of our patients were diagnosed at stage III, while 38.4% (n = 48) presented at stage IV. This was found to be similar for other major forms of cancer studied in Libya[10]. The major problem in the Libyan scenario is late presentation. This could be due a number of different reasons, among them awareness and social stigma. Transport difficulties in rural areas as well as the distance to Benghazi also serve as a hindrance to early detection.

Screening programs would greatly increase the catchment rate of our CRC patients before they reach these late stages. This is especially important in the sporadic cases, which form the majority of cases.

The Libyan diet is traditional in certain areas and modern (Westernized) in others. This is a reflection of the rural-urban differences that exist. With the increase of consumption of Western-style cooking and the downwards trend of traditional food, it is expected that there would be a rise in the incidence of CRC. However, a long term study is required in order to determine such a trend. Further risk factors also exist in Libyan society, such as a high rate of diabetes mellitus, smoking, obesity, etc.

Certain limitations, however, need to mentioned, namely the quality of the patient records. In the gathering of this data, not all the parameters were available for all the patients and hence they were excluded from the analysis. The data that was gathered for this study was from one center and, even although it is the sole oncological center in the region, there will surely be a certain number of missed cases or patients who immediately sought care abroad without referral to our center first. Additionally, while this data is representative of eastern Libya, we cannot generalize this for all of Libya. In cancer epidemiology, stark differences may exist between different regions of a country.

In conclusion, Libya has a higher rate of CRC than neighboring countries, with an incidence that is closer to the European figures. Increasingly, younger ages are being afflicted and a higher proportion of patients are among the > 40 years subset. Urban-rural differences were observed in the Libyan scenario. A major problem is delayed presentation with a large proportion of patients seeking medical care at advanced or late stages with a poor prognosis. Screening programs are sorely needed in Libya in order to combat presentation at late stages.

COMMENTS

Background

Cancer epidemiology is a rapidly growing field that has made great strides in the last few decades; however, it has always been developed countries that have contributed the majority of data and figures. As a consequence, most of the information available on cancer incidence is based on those societies. In the developing world, this information is extracted with more difficulty. This is especially true in Libya where data gathering is notoriously difficult (for a myriad of reasons). For the first time, colorectal cancer (CRC) patients in Libya were studied and the findings were presented.

Research frontiers

There is now a focus on customization of epidemiology for different countries and even different regions within a single country. Preventive medicine has taken the lead in epidemiology and a baseline needs to be determined before any cancer plan can be established at a national or local level.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Colon cancer was found to be the leading malignancy in Libyan males and the second most prevalent among females. Despite that, there has never been a study on CRC in Libya. Using population data from the 2006 Libyan census with projections for future years, the age-standardized rates (ASR) was calculated. Various parameters were gathered for the patients, among them, age, nationality, affected site within the colon, histopathological grade and the clinical stage. The geographical distribution of CRC patients in Libya was also studied for the first time.

Applications

Using the findings from this study, the health authorities in Libya can finally lay a plan to help combat CRC. A major problem in the Libyan scenario is late presentation, so increased awareness among the populace and a higher index of suspicion among clinicians would surely save countless lives. Certain regions contributed more in terms of patient load and hence more focus needs to be placed there.

Terminology

ASR: ASR is an internationally used measure of new cancer cases relative to the standard world population (as stated in the Cancer in Five Continents series).

Peer review

It is a descriptive study that intended to demonstrate the effect of changing food habits in Libyan people. This is an interesting article.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Lin JH, Parsak C, Seetharaman H S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu SQ

References

- 1.Gatta G, Faivre J, Capocaccia R, Ponz de Leon M. Survival of colorectal cancer patients in Europe during the period 1978-1989. EUROCARE Working Group. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:2176–2183. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00327-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Repetto L, Venturino A, Fratino L, Serraino D, Troisi G, Gianni W, Pietropaolo M. Geriatric oncology: a clinical approach to the older patient with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:870–880. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wymenga AN, Slaets JP, Sleijfer DT. Treatment of cancer in old age, shortcomings and challenges. Neth J Med. 2001;59:259–266. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(01)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Cancer epidemiology in the elderly. Crit Rev OncolHematol. 2001;39:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Mistiri M, Pirani M, El Sahli N, El Mangoush M, Attia A, Shembesh R, Habel S, El Homry F, Hamad S, Federico M. Cancer profile in Eastern Libya: incidence and mortality in the year 2004. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1924–1926. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker J, Quirke P. Biology and genetics of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 Suppl 7:S163–S172. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)80018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staib L, Link KH, Blatz A, Beger HG. Surgery of colorectal cancer: surgical morbidity and five- and ten-year results in 2400 patients--monoinstitutional experience. World J Surg. 2002;26:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young A, Rea D. ABC of colorectal cancer: treatment of advanced disease. BMJ. 2000;321:1278–1281. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christopoulou A. Chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8 Suppl 1:s43–s46. doi: 10.1007/s10151-004-0108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodalal Z, Azzuz R, Bendardaf R. Cancer in Eastern Libya: Results from Benghazi Medical Center. World J Gastroenterol. 2014:in press. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–543. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salim EI, Moore MA, Al-Lawati JA, Al-Sayyad J, Bazawir A, Bener A, Corbex M, El-Saghir N, Habib OS, Maziak W, et al. Cancer epidemiology and control in the arab world - past, present and future. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tazi M, Benjaafar N, Er-Raki A. Incidence des Cancers a Rabat-Annee 2005. Registre des Cancers de Rabat 2009. Accessible from: http://www.fmp-usmba.ac.ma/pdf/Documents/cancer_registry_mor_rabat.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benider A, Bennani M, Harif M. Registre des Cancers de la Region du grand Casablanca, Annee 2004. Registre des Cancers du grand Casablanca, 2007. Available from: http: // www.contrelecancer.ma/site_media/uploaded_files/Registre_des_Cancers_de_la_Re%C3%BCgion_du_grand_Casablanca_2004.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curado M, Edwards B, Shin H, Storm H, Ferlay J, Heanue M, Boyle P, eds . Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Lyon: IARC Scientific Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Registre des Tumeurs d’Alger Annee 2006. Ministere del la Sante et de la Population: Institut National de Sante Publique, 2007. Available from: URL: http: //www.sante.dz/insp/registre-tumeurs-alger-2006.pdf; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben Abdallah M, Zehani S, Hizem Ben Ayoub W. North Tunisia Cancer Registry. Third report: 1999-2003. Internal report; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sellami A, Sellami Boudawara T. Incidence des cancers dans le Gouvernorat de Sfax 2000-2002. Institut National de la Santé Publique, 2007. Available from: http: //www.emro.who.int/images/stories/tunisia/documents/incidence_des_cancers_dans_le_gouvernorat_de_sfax_2000-2002_Ahmed_SellamiMohamed_Hsairi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Mistiri M, Verdecchia A, Rashid I, El Sahli N, El Mangush M, Federico M. Cancer incidence in eastern Libya: the first report from the Benghazi Cancer Registry, 2003. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:392–397. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.First Annual Report: Population Based Cancer Registry. Sibratha: Sibratha Cancer Registry, 2008. Accessible from: http: //www.ncisabratha.ly/nci/filesystem/uploads/REPORT1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkin D, Whelan S, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas D. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2002. pp. 715–718 [accessible through IARC website: www.iarc.fr]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart B, Kleihues P. World Cancer Report 2003. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zanetti R, Tazi MA, Rosso S. New data tells us more about cancer incidence in North Africa. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ansari R, Mahdavinia M, Sadjadi A, Nouraie M, Kamangar F, Bishehsari F, Fakheri H, Semnani S, Arshi S, Zahedi MJ, et al. Incidence and age distribution of colorectal cancer in Iran: results of a population-based cancer registry. Cancer Lett. 2006;240:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gado A, Ebeid B, Abdelmohsen A, Axon A. Colorectal cancer in Egypt is commoner in young people: Is this cause for alarm? Alex J Med. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veruttipong D, Soliman AS, Gilbert SF, Blachley TS, Hablas A, Ramadan M, Rozek LS, Seifeldin IA. Age distribution, polyps and rectal cancer in the Egyptian population-based cancer registry. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3997–4003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i30.3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pal M. Proportionate increase in incidence of colorectal cancer at an age below 40 years: an observation. J Cancer Res Ther. 2006;2:97–99. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.27583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dey S, Soliman AS, Hablas A, Seifeldein IA, Ismail K, Ramadan M, El-Hamzawy H, Wilson ML, Banerjee M, Boffetta P, et al. Urban-rural differences in breast cancer incidence in Egypt (1999-2006) Breast. 2010;19:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]