Abstract

Structured lipids were prepared from mustard oil by enzymatic acidolysis reaction with capric acid (C10) using lipase enzyme TLIM from Thermomyces lanuginosus as biocatalyst. Parameters such as substrate molar ratio, enzyme concentration, reaction temperature, stirring speed and time of maximum incorporation, were studied for the optimization of the reaction. The optimized set of process conditions was predicted by response surface methodology (RSM) and genetic algorithm (GA). The robustness of GA and RSM was evaluated using regression coefficient and p value. The R2 found out by GA was 0.996 while from RSM was 0.973. The results proved that GA models have better performance than RSM models. From the result, it could be concluded that optimal conditions for synthesis of capric acid rich mustard oil were: Temperature = 39.5 °C ; time = 21.1 hr; Substrate ratio = 3.5; Enzyme content = 8.8%; Speed = 570.8 rpm.

Keywords: Biocatalyst, Structured lipid, Response Surface Methodology (RSM), Genetic Algorithm (GA)

Introduction

Now a day’s medium chain fatty acid containing triacylglycerol (TAG) is gaining importance for its special properties of reducing body weight, lowering of cholesterol synthesis and oxidative stability. Its distinctive characteristics such as low viscosity, low melting point and high solubility in water makes it easy to transport and metabolize. The long-term safety of medium-chain fatty acids in laboratory animals and humans was also confirmed in the period of 1950–60s, and its clinical application for mal-digestion/ mal-absorption syndrome was initiated. Currently, medium chain fatty acids (MCFA) containing TAG (MCT) is used as powdered oil, cooking oil, therapeutic diets, internal nutrients and transfusion solutions (Takeuchi et al. 2004).

Bio-catalysts have already made a good position in several fields of applications like food, pharmaceuticals, leather and textile and lipid chemistry and the modification of fats and oils on the basis of health matters by lipase-catalysed reactions has been paid attention since the last two decades (Camp et al. 1998). It is considered that structured lipids can be prepared effectively by transacylation based on the proper selection of lipase with higher transacylation or hydrolysis activities for specific fatty acids (Huyghebaert et al. 1994). There is lots of literature in which the production of MCT–rich structured lipids using lipase as biocatalyst was described (Kawashima et al. 2001; Miura et al. 1999; Fomuso and Akoh 1998; Babayan 1987; Akoh and Lee 1997).

Any biological process, especially pertaining to food processing, which is a complex interplay of several intrinsic biochemical properties and influences process variables, warrants a strategic application of modeling and optimization tools like response surface methodology (RSM), genetic algorithm (GA) etc. to obtain a feasible optimum yield. Hence, determination of optimal conditions for processing is the key to ideal industrial processing. The effectiveness of RSM in optimization of processing conditions in the area of food technology ranging from raw materials to final products has been well documented (Gan et al. 2007; Madamba 2002). Besides RSM, soft computing methodologies, namely GA, have been recently found to offer novel solutions to improve control and modeling in food processing. GA has evolved as an ideal technique to solve diverse optimization problems in food and biochemical engineering (Sarkar and Modak 2003).

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and genetic programming (GP) have been found to offer advantages to deal with system modeling and optimization, especially for complex and nonlinear systems. GP has been applied to a wide range of problems in artificial intelligence, engineering and science, chemical and biological processes, and mechanical models including symbolic regression. In recent years only a few studies have been reported related to the use of GAs in the field of food science. Izadifar and Jahromi used GAs for the optimization of vegetable oil hydrogenation process (Izadifar and Jahromi 2007). Dutta et al studied optimization of a protease production process by using GAs (Dutta et al. 2005). Hanai et al applied GAs for the determination of process orbits in the koji making process and Liu et al used GAs to predict moisture content of grain drying process (Hanai et al. 1999).

The present study aims at modeling and optimization of incorporation of capric acid into mustard oil, taking into consideration substrate ratio, time, temperature, enzyme content and stirring speed as the influencing parameters in view of maximizing the capric acid incorporation by employing statistical optimization techniques and soft computing tools.

Materials and methods

Materials

Mustard oil was extracted from brown mustard seed by solvent extraction method and physically refined and bleached in the laboratory. Capric acid (C10:0) (100% pure) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Company and purity analysis was done by gas chromatography (GC). Immobilized lipase Lypozyme TLIM was a gift from Novozyme India Ltd., Bangalore, India. The original moisture content of the enzyme (2%, w/w) was kept intact to initiate the reaction. All other chemicals used were of Analytical Grade and procured from Merck India Ltd. Mumbai, India.

Acidolysis reaction

Acidolysis reaction was performed between mustard oil and capric acid with variable reaction parameters such as temperature, substrate molar ratio, amount of enzyme, stirring speed and time course of reaction. The reaction was carried out at a temperature range of 45–70 °C. The substrate molar ratio was taken in the range between 1:2–1:5 (oil:acid).The enzyme content was varied between 5–12% (w/w). The range of speed at which the reaction was carried out was between 300–700 rpm. The reaction was carried out for 72 hr and the products were collected at different intervals. Intermittent samples were filtered, separated by thin layer chromatography (TLC) and the fatty acid composition of the TAG part was analyzed by GC.

Chromatographic analysis of oil

Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) of respective TAG samples were prepared by the method described by Metcalfe (Metcalfe et al. 1966) and subsequently injected to an analytical gas chromatograph instrument (Agilent 6890 Series Gas chromatograph) equipped with a FID detector and capillary DB-Wax column (30 m L, 0.32 mm I.D, 0.25 μm FT). N2, H2 and airflow rate was maintained at 1 ml/min, 30 ml/min and 300 ml/min respectively. Inlet & detector temperature was kept at 250 °C and the oven temperature was programmed as 150–190–230 °C with increase rate of 15 °C/min and 5 min hold up to 150 °C and 4 °C/min with 10 min hold up to 230 °C. The percentage proportions of fatty acids were calculated from the respective peak area.

Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

Factors considered important were temperature (Te = 45–70 °C), reaction time (t = 6–72 h), substrate molar ratio; i.e., mustard oil:capric acid (Sr = 1:2–1:5), enzyme amount; i.e., weight percent of enzyme on the basis of weight of total substrates (En = 5–12%) and speed (S = 300–700 rpm). RSM was used to optimize reaction parameters. Box-Behnken (BB) experimental design, generated by using MINITAB 14 was adopted in this study for five different independent variables. Fifteen experimental settings were generated by the principle of RSM. The quadratic polynomial regression model was assumed for predicting Y variable (Ic = degree of incorporation of capric acid into mustard oil). The model proposed for the response of Y fitted Eq. (1) as follows:

|

1 |

Where Y is response variable (Ic, %). b0 is constant coefficient of intercept, b1-b5 are constant coefficients of linear terms, b6-b10 are constant coefficients of quadratic terms and b11-b20 are constant coefficients of interaction terms, respectively, and X1-X5 are independent variables (Te, t, Sr, En and S). Response surface methodology (RSM) method was followed according to different literatures where RSM was used for optimization (Alam et al. 2010; Chakraborty et al. 2011; Garg and Singh 2010; Wadikar et al. 2010; Modha and Pal 2011; Xu et al. 1998).

Genetic algorithm technique

The genetic algorithm (GA) method is an optimization and search technique based on the principles of genetics and natural selection idea. The method was introduced by Holland (Holland 1995) between the 1960s and 1970s. GA as a population-based search technique maintains populations of potential solutions during the search procedures. It needs a fitness (objective) function that assigns scalar weight to a particular solution to evaluate each potential solution. The algorithm starts searching once the representation system and evaluation function are determined. The initial random population size of strings to form the first generation is shaped and the fitness function evaluates each solution of the first generation. Superior solutions taking higher weights are employed to generate the next generation by some genetic operations. The evaluation and generation process repeats until the optimal solution is reached (Goldberg 1986).

The first step in applying GA was to know the best set of operators that give the best possible efficiency. Efficient optimization algorithm means less computational time and fewer number of objectives function evaluations. For that reason, we used stochastic uniform as a selection function and heuristic as a crossover function. GA is based on the classical genetic operators such as generation, mutation and crossover. GA has been used to determine optimal operational parameters for several industrial processes and other practical applications such as building parameters (Wright 1996). Here we are using GA for optimization of the acidolysis reaction.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were repeated thrice. All the data were presented as mean ± S.D. Significance was calculated using two way ANOVA. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Changes in fatty acid composition of mustard oil after acidolysis reaction

The effective production of capric acid rich mustard oil by the exchange of fatty acids at different positions in mustard oil for capric acid by means of Candida antarctica lipase is described in Table 1. Following the trend of the previous two reactions in this case too the incorporation of fatty acids increased with time. On acidolysis of mustard oil, capric acid incorporation was brought about firstly by replacing palmitic and oleic acids. As the time of the reaction increased capric acid incorporation in mustard oil was also increased by removal of erucic acid.

Table 1.

Fatty acid composition (%w/w) triglycerides obtained from acidolysis reaction between mustard oil and capric acid

| Fatty acid | C10:0 | C16:0 | C16:1 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C18:3 | C20:0 | C20:1 | C22:1 | C24:0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | |||||||||||

| Original mustard oil | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 12.2 | 17.2 | 9.3 | 0.8 | 5.1 | 51.1 | 0.7 |

| After 72 h of reaction | 19.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 8.4 | 14.6 | 9.9 | 0.3 | 4.6 | 41.4 | 0.2 |

Optimization of reaction parameters

The ultimate goal of our study was to model the highest incorporation (Ic) of capric acid (%w/w) in mustard oil when TLIM was used as the biocatalyst for the acidolysis reaction. In our study, we used refined, bleached mustard oil and commercially available capric acid as the substrates.

The major factors affecting the product formation were investigated in this study like different temperatures (°C), substrate ratios (molar), enzyme concentration (%w/w), speed (rpm) and time (hr).

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) model & optimization of reaction parameters using RSM

RSM was applied to model the incorporation of capric acid into mustard oil to produce capric acid rich mustard oil, with 5 reaction parameters: temperature (Te), reaction time (t), substrate molar ratio (Sr), enzyme % (En) and speed (S). RSM enabled us to obtain sufficient information for statistically acceptable results using reduced number of experiment sets, and is an efficient method to evaluate the effects of multiple parameters, alone or in combination, or response variables. Table 2 lists the levels of Incorporation at each of the 15 experimental sets generated by the principles of RSM used in this study and the levels ranged from as low as 2.5% to as high as 23%. The results were analyzed by using ANOVA, i.e. analysis of variance suitable for the experimental design. ANOVA tables for incorporation of capric acid in mustard oil were obtained using MINITAB 14 software to evaluate the significance of different parameters. The results are shown in Table 3. The model F value of 38.45 implies that the model was significant. Model F-value is calculated as ratio of mean square regression and mean square residue. Model p-value has been found to be very low (p < 0.0001) for all the response variables. This resignifies the efficacy of the model. The p-values are used as a tool to check the significance of each of the coefficients, which, in turn, is necessary to understand the pattern of the mutual interactions between the independent variables. The smaller the magnitude of p, more significant is the corresponding coefficient. Values of p < 0.05 indicate that the model terms are significant. The coefficient estimates and the corresponding p-values suggest that, among the independent variables used in the study, the linear terms X1 (Sr), X2 (temp.), X3 (time), X4 (speed), X5 (En) and the quadratic terms X21, X22, X23, X24 and X25 (p < 0.0001) have the greatest effect on each of the response variables. The mutual interaction between independent variables has been found to be of least importance as p-values are well above 0.05, which is evident from Table 3. The fit of the models was also expressed with the coefficient of determination R2, which was found to be 0.973 for incorporation of capric acid.

Table 2.

Box-Behnken design results for tansesterification between capric acid and mustard oil

| Run | Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | Enzyme concentration (% w/w) | Speed (rpm) | Substrate Ratio | Response Incorporation (% w/w)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | 6 | 5 | 300 | 1:2 | 16.67 |

| 2 | 45 | 72 | 12 | 550 | 1:3 | 4.8 |

| 3 | 50 | 24 | 8 | 300 | 1:2 | 15.3 |

| 4 | 50 | 48 | 8 | 550 | 1:3 | 9.3 |

| 5 | 50 | 6 | 5 | 700 | 1:5 | 4.9 |

| 6 | 60 | 48 | 10 | 300 | 1:2 | 14.76 |

| 7 | 60 | 24 | 10 | 550 | 1:3 | 19.9 |

| 8 | 45 | 24 | 10 | 650 | 1:4 | 23.0 |

| 9 | 70 | 72 | 12 | 300 | 1:2 | 10.0 |

| 10 | 70 | 6 | 5 | 550 | 1:3 | 2.5 |

| 11 | 50 | 72 | 12 | 650 | 1:4 | 12.1 |

| 12 | 60 | 6 | 5 | 650 | 1:4 | 8.3 |

| 13 | 60 | 24 | 8 | 700 | 1.5 | 14.6 |

| 14 | 70 | 48 | 10 | 700 | 1:5 | 10.6 |

| 15 | 45 | 72 | 12 | 700 | 1.5 | 6.6 |

Table 3.

ANOVA for the experimental results of percentage of capric acid (% w/w) incorporated optimized by RSM

| Sources | D.f. | SS | MS | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 15 | 554.46 | 61.61 | 38.45 | <0.0001 |

| Linear terms | 5 | 132.07 | 44.02 | 27.47 | <0.0001 |

| Quadratic terms | 5 | 410.90 | 136.97 | 85.47 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction terms | 5 | 11.49 | 3.83 | 2.39 | 0.1540 |

| Residual error | 9 | 11.22 | 1.60 | – | – |

| Lack of fit | 5 | 10.31 | 3.44 | 15.07 | 0.0120 |

| Pure error | 6 | 0.91 | 0.23 | – | – |

Df degrees of freedom; SS sum of squares; MS mean square

The optimum values were found by solving the regression equation analytically (Agarry et al. 2008). The equation was obtained by submitting the levels of the factors into the regression equation. For optimization of incorporation of capric acid in mustard oil, desirability functions of RSM were used. The optimal values for the test variables of capric acid incorporation were obtained as oil to acid ratio of 1:4, reaction temperature of 45 °C, speed at 650 rpm, enzyme amount as 10% (w/w) and reaction time 24 hr. RSM is useful not only for the additional knowledge supplied about the process, but also for the potentials for process control (Kalil et al. 2000).

Genetic Algorithm (GA) model and optimization of reaction conditions by GA

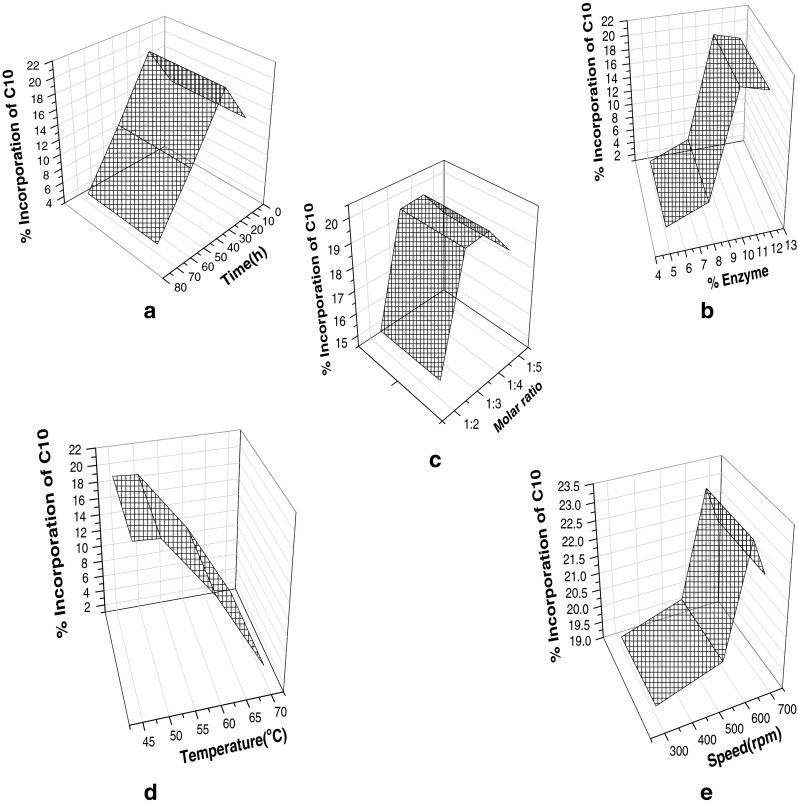

Total 15 sets of experimental study were used as training and testing tests for the GA architecture. Plots were used for optimization of the conditions of the tansesterification reactions by GA. Five plots between the five parameters and Ic were constructed to optimize the reaction parameters (Fig. 1). From the result of the in Fig. 1 graphs, it could be concluded that optimal conditions for synthesis of capric acid rich mustard oil were: Te = 39.5 °C; t = 21.1 hr; Sr = 3.5; En = 8.8%; S = 570.8 rpm. The robustness of the proposed GA model was proven via plotting the graphs.

Fig. 1.

Plots between two parameters for % incorporation of capric acid in mustard oil (a) temperature (Te) and Ic; (b) molar ratio (Sr) and Ic; (c) enzyme % (En) and Ic; (d) speed (S) and Ic; (e) time (t) and Ic

The overall performances of all the sets were evaluated by the correlation cefficient (R2) and mean standard error (MSE). The R2 and MSE were calculated from the comparison between predicted values of incorporation of capric acid and the actual values. Thus the predicted response was experimentally verified. The agreement between predicted value and incorporation rate of capric acid confirms the significance of the model. The results prove that there was a linear relationship between the two set of values with high correlation (R2 = 0.996) and relatively low error. To test the fit of the model, the regression equation and determination coefficient (R2) was evaluated. In this case the value of the determination coefficient (R2 = 0.996) indicates that the sample variation of 99.6% for molar incorporation of capric acid is attributed to the independent variables and only 0.4% of the total variations are not explained by the model. Thus a high value of correlation coefficient is good to advocate a high significance of the model. A higher value of the correlation coefficient justifies an excellent correlation between the independent variables (Yuan et al. 2008). The above findings exhibit a successful performance of the GA model in optimizing the reaction. The results here were also analyzed by using ANOVA, i.e. analysis of variance suitable for the experimental design. The results are shown in Table 4. The model F value of 14.90 implies that the GA model was also significant.

Table 4.

ANOVA table a for the experimental results of percentage of capric acid incorporated (% w/w) optimized by GA

| Df | SS | MS | F value | Prob>F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1 | 524.10 | 52.41 | 14.90 | 0.324 |

| Error | 10 | 3.52 | 0.35 | ||

| Total | 11 | 527.62 | 52.46 |

a Df degrees of freedom; SS sum of squares; MS mean square

RSM vs GA

Proposed RSM based incorporation of capric acid compared with GA has been presented in the study. The same reaction parameters were applied in both the models. Similar reaction parameters were optimized in both the models. The robustness of GA and RSM is evaluated using regression coefficient and p value. The R2 found out by GA is 0.996 while from RSM was 0.973. Thus the regression coefficient value of GA is more close to unity in comparison to RSM which proves that the incorporation rate of capric acid by GA is more close to the theoretically predicted incorporation rate. Therefore it can be said that GA models have better performance than RSM models. Randomly based algorithms such as the GA procedure, is more effective method leading the optimizer to locate the global optimum especially when the parameter searching space is extremely wide.

Conclusion

A genetic algorithm model for incorporation of capric acid in mustard oil was proposed using a set of experimental data. The evaluation of the GA model with test data indicated considerable robustness of the model. The application of this model lies in obtaining optimum reaction conditions using GA, which results in maximization of capric acid incorporation into mustard oil. Validation of the GA model indicated its considerable effectiveness. The optimization of the process was also performed by RSM, but GA proved to be more effective. The reaction conditions were same for both the models. The maximum incorporation of capric acid in mustard oil was 23%.

Acknowledgements

The financial support for the research work was received from Dept. of Science & Technology, Govt. of India.

References

- Agarry SE, Solomon BO, Layokun SK. Optimization of process variables for the microbial degradation of phenol by Pseudomonas aeruginosa using response surface methodology. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7:2409–2416. [Google Scholar]

- Akoh CC, Yee L. Enzymatic synthesis of position specific low calorie structured lipids. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1997;74:1409–1413. doi: 10.1007/s11746-997-0245-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MS, Singh A, Sawhney BK. Response surface optimization of osmotic dehydration process for aonla slices. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47:47–54. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0014-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babayan VK. Medium chain triglycerides and structured lipids. Lipids. 1987;22:417–420. doi: 10.1007/BF02537271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp V, Goeman P, Huyghebaert A. Enzymatic synthesis of structure-modified fats. In: Christophe AB, editor. Structural modified food fats: synthesis, biochemistry, and use. Champaign: AOCS press; 1998. pp. 20–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty SK, Kumbhar BK, Chakraborty S, Yadav P. Influence of processing parameters on textual characteristics and overall acceptability of millet enriched biscuits using response surface methodology. J Food Sci Technol. 2011;48:167–174. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta JR, Dutta PK, Banerjee R. Modelling and optimization of protease production by a newly isolated Pseudomonas sp. using a genetic algorithm. Process Biochem. 2005;40:879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2004.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fomuso LB, Akoh CC. Structured lipids: lipase catalsed interestrification of tricaproin and trilinolein. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1998;75:405–410. doi: 10.1007/s11746-998-0059-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gan HE, Karim R, Muhammad SKS, Baker JA, Hashim DM, Rahman RA. Optimization of the basic formulation of a traditional baked cassava cake using response surface methodology. LWT- Food Sci Technol. 2007;40:611–618. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2006.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garg SK, Singh DS. Optimization of extrusion conditions for defatted soy-rice blend extrudates. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47:606–612. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0117-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DE. Genetic algorithms in search, optimization and machine learning. New York: Addison-Wesley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hanai T, Honda H, Ohkussu E, Ohki T, Tohyama H, Muramatsu T, Kobayashi T. Application of an artificial neural network and genetic algorithm for determination process orbits in the koji making process. J Biosci Bioeng. 1999;87:507–512. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(99)80101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JH. Adaption in natural and artificial systems. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Huyghebaert A, Verhaeghe D, de Moor H. Fat products using chemical and enzymatic interesterification. In: Moran DPJ, Rajah KK, editors. Fats in food products. London: Blackie Academic and Professional; 1994. pp. 319–345. [Google Scholar]

- Izadifar M, Jahromi MZ. Application of genetic algorithm for optimization of vegetable oil hydrogenation process. J Food Eng. 2007;78:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.08.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil SJ, Maugeri F, Rodrigues MI. Response surface analysis and simulation as a tool for bioprocess design and optimization. Process Biochem. 2000;35:539–550. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(99)00101-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima A, Shimada Y, Yamamoto M, Sugihara A, Nagao T, Komemushi S, Tominaga Y. Enzymatic synthesis off high purity structured lipids with caprylic acid at 1,3 positions and polyunsaturated fatty acids at 2-position. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2001;78:611–616. doi: 10.1007/s11746-001-0313-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madamba PS. The response surface methodology: an application to optimize dehydration operations of selected agricultural crops. LWT- Food Sci Technol. 2002;35:584–592. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe LD, Schmitz AA, Polka JR. Rapid preparation of fatty acid esters from lipids for gas chromatographic analysis. Anal Chem. 1966;38:514–515. doi: 10.1021/ac60235a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miura S, Ogawa A, Konishi H. A rapid method for enzymatic synthesis and purification of the structured triacylglycerol, 1,3 dilauroyl-2-oleoyl-glycerol. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1999;76:927–931. doi: 10.1007/s11746-999-0108-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modha H, Pal D. Optimization of Rabadi-like fermented milk beverage using pearl millet. J Food Sci Technol. 2011;48:190–196. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0146-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar D, Modak JM. Optimization of fed-batch bioreactors using genetic algorithms. Chem Eng Sci. 2003;58:2283–2296. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2509(03)00095-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Sekine S, Seto A. Medium-chain fatty acids—Nutritional function and application to cooking oil. Lipid Technol. 2004;20:9–12. doi: 10.1002/lite.200700097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wadikar DD, Nanjappa C, Premavalli KS, Bawa AS. Development of ready-to-eat appetisers based on pepper and their quality evaluation. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47:638–643. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0105-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. HVAC optimizing studies: sizing by genetic algorithm. Build Serv Eng Tech. 1996;17:1–14. doi: 10.1177/014362449601700101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Skands ARH, Alder-Nissen J, Hoy CE. Production of specific structured lipids by enzymatic interesterification: optimization of the reaction by response surface design. Lipids. 1998;100:463–471. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4133(199810)100:10<463::AID-LIPI463>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Liu J, Shi J, Tong J, Huang G. Optimization of conversion of waste rapeseed oil with high FFA to biodiesel using response surface methodology. Renew Energ. 2008;33:1678–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2007.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]