Abstract

Excitation-contraction coupling (ECC) in the cardiac myocyte is mediated by a number of highly integrated mechanisms of intracellular Ca2+ transport. Voltage- and Ca2+-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels (LCCs) allow for Ca2+ entry into the myocyte, which then binds to nearby ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and triggers Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in a process known as Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. The highly coordinated Ca2+-mediated interaction between LCCs and RyRs is further regulated by the cardiac isoform of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKII). Because CaMKII targets and modulates the function of many ECC proteins, elucidation of its role in ECC and integrative cellular function is challenging and much insight has been gained through the use of detailed computational models. Multiscale models that can both reconstruct the detailed nature of local signaling events within the cardiac dyad and predict their functional consequences at the level of the whole cell have played an important role in advancing our understanding of CaMKII function in ECC. Here, we review experimentally based models of CaMKII function with a focus on LCC and RyR regulation, and the mechanistic insights that have been gained through their application.

Keywords: cardiac myocyte, excitation-contraction coupling, cell signaling, CaMKII, computational modeling

Introduction

Cardiac electrophysiology is a discipline with a rich and deep history dating back more than a half-century. Much of our understanding of fundamental biological mechanisms in this field comes from experimental research coupled with integrative mathematical modeling. The goal of this modeling has been to achieve a quantitative understanding of the functional mechanisms and relationships that span from the level of molecular structure and function to integrated cardiac myocyte behavior in health and disease. Advances in computational techniques and hardware have led to the recent development of many sophisticated large-scale models of heart tissue, in which these electrophysiological myocyte models are the fundamental building blocks. Some of the most fundamental advances in computational cell biology, including formulation of dynamic models of voltage-gated ion channels, mitochondrial energy production, membrane transporters, intracellular Ca2+ dynamics, and signal transduction pathways have emerged from this field. One such signaling pathway is that involving the Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase (CaMKII), which targets and functionally regulates a number of proteins that are central to cardiac excitation-contraction coupling (ECC), and has been identified as a promising new target for antiarrhythmic therapy in patients with heart failure (Rokita and Anderson, 2012). This review focuses on the role of experimentally based models of CaMKII function with a focus on L-type Ca2+ channel (LCC) and ryanodine receptor (RyR) regulation, and the mechanistic insights that have been gained through their application.

The nature of ECC is linked closely to the micro-anatomical structure of the cell. Sarcomeres, the basic units of contractile proteins, are bounded on both ends by the t-tubular system (Soeller and Cannell, 1999; Bers, 2001). The t-tubules extend deep into the cell and approach the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), an intracellular luminal organelle involved in the uptake, sequestration and release of Ca2+. The junctional SR (JSR) is the portion of the SR most closely approximating (within 12–15 nm Franzini-Armstrong et al., 1999) the t-tubules. The close proximity of these two structures forms a microdomain known as the dyad. RyRs are Ca2+-sensitive Ca2+-release channels which are preferentially located in the dyadic region of the JSR membrane. In addition, LCCs are preferentially located within the dyadic region of the t-tubules, where they are in close opposition to the RyRs. The process by which Ca2+ enters the myocyte during the initial depolarization stages of the action potential (AP) via voltage-gated LCCs and triggers the opening of RyRs, and hence JSR Ca2+ release, is known as Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) and comprises the initial transduction event of ECC. Recent imaging studies have demonstrated that dyadic clefts are small, where junctions contain an average of 14 RyRs, with some clusters incompletely filled with RyRs, and with a large fraction of clusters closely spaced within 20–50 nm, suggesting that smaller clusters may act together to function as a single site of CICR (Baddeley et al., 2009; Hayashi et al., 2009).

The elucidation of CICR mechanisms became possible with the development of experimental techniques for simultaneous measurement of L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) and Ca2+ transients, and detection of local Ca2+ release events known as Ca2+ sparks (Cheng et al., 1993). The evidence for tight regulation of SR Ca2+ release by triggering LCC current (for a review see Soeller and Cannell, 2004) gave rise to and later verified the local control theory of ECC (Stern, 1992). The mechanism of local control predicts that tight regulation of CICR is achieved because LCCs and RyRs are regulated by local dyadic Ca2+. It is now widely accepted that CaMKII, a ubiquitous Ca2+-dependent protein that can become highly activated in the dyad (Currie et al., 2004; Hudmon et al., 2005; Maier, 2005), can modulate CICR via phosphorylation of a number of ECC proteins including LCCs and RyRs (Maier and Bers, 2007). CaMKII modulates LCCs via a Ca2+-dependent positive-feedback regulatory mechanism known as ICaL facilitation (Anderson et al., 1994; Xiao et al., 1994; Yuan and Bers, 1994). This is observed as a positive staircase in current amplitude in combination with a slower rate of ICaL inactivation upon repeated membrane depolarization. Although multiple mechanisms have been suggested to underlie ICaL facilitation, experiments from Dzhura et al. (2000) demonstrated that CaMKII-dependent ICaL facilitation alters the behavior of LCCs such that high activity gating modes with prolonged open times are more likely to occur. The specific functional effects of CaMKII phosphorylation of RyRs remain controversial. CaMKII has been shown to increase (e.g., Wehrens et al., 2004) or decrease (e.g., Lokuta et al., 1995) the channel open probability. Inconsistencies in experimental findings regarding the role of CaMKII on RyR function may not be surprising given the methodological differences between the studies. In addition, the high sensitivity of RyR gating to both cytosolic and SR Ca2+ makes it difficult to interpret experiments in which these Ca2+ concentrations are not tightly controlled. In one well designed study, Guo et al. (2006) developed an experimental protocol that overcame this challenge and provided strong evidence that CaMKII mediated phosphorylation of RyRs increases channel open probability. Such an increase is also consistent with transgenic studies of CaMKII overexpression which report increased Ca2+ spark frequency in response to elevated CaMKII activity (Maier et al., 2003; Kohlhaas et al., 2006).

The CaMKII holoenzyme exists as an elaborate macromolecular complex consisting of two stacked ring-shaped hexamers (Hudmon and Schulman, 2002). Each of the holoenzyme's 12 subunits can be activated through the binding of Ca2+-bound CaM (Ca2+/CaM) to the CaMKII regulatory domain in response to beat-to-beat transient increases of intracellular Ca2+ concentration. In cardiac myocytes, an activated CaMKII molecule can undergo autophosphorylation by neighboring subunits at threonine amino acid residues in its regulatory domain, which allows the kinase to retain activity even upon dissociation of Ca2+/CaM (Meyer et al., 1992). An alternative mechanism of oxidative CaMKII activation has also been identified (Erickson et al., 2008). As a result of the fact that CaMKII regulates multiple protein targets (both directly and indirectly involved in ECC), and that the effect of CaMKII mediated phosphorylation on any particular target protein may involve complex alterations in biophysical function (e.g., mode-switching behavior of LCCs), the task of elucidating its role in cardiac function in both normal and failing hearts continues to present great challenges and cannot be accomplished via experiments alone. Some recent advances in understanding the mechanisms of CaMKII-dependent function in cardiac myocytes have been discovered by coupling mathematical models to experimental observations. In this review we will focus on key models of CaMKII-mediated regulation of LCCs and RyRs arising from both Ca2+/CaM-dependent as well as oxidative activation pathways, the integration of such models into whole-cell models, and the mechanistic insights that have been obtained from this work. A summary of the models covered here is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key features of CaMKII models in cardiac ECC.

| Cell model | Species | Parent ECC model | CaMKII activation model | Included CaMKII targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hund and Rudy, 2004 | Dog | Luo and Rudy, 1994 | Hanson et al., 1994 | LCCs, RyRs, SERCA/PLB |

| Iribe et al., 2006 | Guinea pig | Noble et al., 1991 | Conceptual kinetic model | LCCs, RyRs, SERCA |

| Livshitz and Rudy, 2007 | Guinea pig/Dog | Luo and Rudy, 1994; Hund and Rudy, 2004 | Hanson et al., 1994 | LCCs, RyRs, SERCA/PLB |

| Grandi et al., 2007 | Rabbit | Shannon et al., 2004 | Static formulation | ICaL, INa, Ito |

| Target parameters adjusted | ||||

| Saucerman and Bers, 2008 | Rabbit | Shannon et al., 2004 | Adapted from Dupont et al. (2003), Gaertner et al. (2004) | no target |

| Hund et al., 2008 | Dog | Hund and Rudy, 2004 | Hanson et al., 1994 | LCCs, RyRs, SERCA/PLB, INa |

| Koivumaki et al., 2009 | Mouse | Bondarenko et al., 2004 | Bhalla and Iyengar, 1999 | LCCs, RyRs, SERCA/PLB |

| Hashambhoy et al., 2009 | Dog | Greenstein and Winslow, 2002 | Dupont et al., 2003 | LCCs |

| Christensen et al., 2009 | Dog | Hund et al., 2008 | Hanson et al., 1994 | LCCs, RyRs, SERCA/PLB, INa |

| Soltis and Saucerman, 2010 | Rabbit | Saucerman and Bers, 2008 | Dupont et al., 2003; Gaertner et al., 2004 | LCCs, RyRs, PLB, INa, Ito |

| Hashambhoy et al., 2010 | Dog | Hashambhoy et al., 2009 | Dupont et al., 2003 | LCCs, RyRs, PLB |

| O'hara et al., 2011 | Human | Hund and Rudy, 2004; Decker et al., 2009 | Hund and Rudy, 2004 | LCCs, PLB, INa, Ito |

| Hashambhoy et al., 2011 | Dog | Hashambhoy et al., 2010 | Dupont et al., 2003 | LCCs, RyRs, PLB, INa |

| Zang et al., 2013 | Dog | Hund and Rudy, 2004 | Hanson et al., 1994 | LCCs, RyRs, INa, Ito, IK1, SERCA |

| Morotti et al., 2014 | Mouse | Soltis and Saucerman, 2010 | Dupont et al., 2003; Gaertner et al., 2004 | LCCs, RyRs, PLB, INa, Ito, IK1, INCX |

Models of Ca2+/CaM-dependent CaMKII activation and regulation

The first model of CaMKII signaling within the context of ECC integrated into the cardiac myocyte was presented by Hund and Rudy (2004). This model, known as the HRd model, incorporates a scheme based on the work of Hanson et al. (1994), where a single population of CaMKII transitions from an inactive to active state in response to elevated subspace Ca2+ levels. CaMKII activity is assumed to modify the function of LCCs and RyRs by slowing their inactivation kinetics, thereby enhancing ICaL and JSR Ca2+ release, respectively. SR Ca2+ uptake was also enhanced by CaMKII activity via its action on phospholamban (PLB) and the SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA). The model predicted that CaMKII plays a critical role in the rate-dependent increase of the cytosolic Ca2+ transient by increasing ECC gain, but that it does not play a significant role in rate-dependent changes of AP duration. Similar results were obtained in the human cardiac AP model of O'hara et al. (2011), which incorporates the role of CaMKII phosphorylation on LCCs, the fast Na+ current (INa), and the transient outward K+ current (Ito1). The HRd model was later updated and used to investigate the role of altered CaMKII signaling in the canine infarct border zone (Hund et al., 2008). Experimentally measured elevation of CaMKII autophosphorylation in this region is reproduced by the model, which indicates that hyperactive CaMKII impairs Ca2+ homeostasis by increasing Ca2+ leak from the SR. A number of additional modeling studies have focused on the role of CaMKII on various aspects of intracellular Ca2+ dynamics. Iribe et al. (2006) incorporated a conceptual CaMKII model into their previous myocyte model (Noble et al., 1991) combined with a model of mechanics (Rice et al., 1999) in order to investigate its role on SR Ca2+ handling and interval-force relations. They found that a relatively slow time-dependent inactivation of CaMKII allowed for the reconstruction of a variety of interval-force relations, including alternans. Koivumaki et al. (2009) built a model of the murine cardiac myocyte to analyze genetically engineered heart models in which CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of LCCs is disrupted or CaMKII is overexpressed. They demonstrated how these genetic manipulations lead to the observed experimental phenotypes as a result of autoregulatory mechanisms that are inherent in intracellular Ca2+ cycling (e.g., steady-state regulation of SR content via Ca2+ release dependent inactivation of LCCs), and that disruption of the regulatory system itself (e.g., via CaMKII overexpression) leads to the most aberrant physiological phenotypes. Livshitz and Rudy (2007) formulated a new model of SR Ca2+ release kinetics and incorporated it into the HRd model in order to better understand regulation of Ca2+ and electrical alternans under various pacing protocols. They found that increased CaMKII activity leads to increased alternans magnitude as well as the appearance of both Ca2+ and electrical alternans at lower pacing rates (where they would not normally occur). This model identifies Ca2+ alternans as the underlying mechanism for electrical alternans, both of which were eliminated with CaMKII inhibition, suggesting this as an antiarrhythmic strategy. Zang et al. (2013) recently developed a new canine myocyte model, also based on the HRd model, to study the role of upregulated CaMKII in heart failure. Similarly, they find that enhanced RyR Ca2+-sensitivity and SR Ca2+ leak mediated by CaMKII overexpression alters Ca2+ handling in a manner that promotes alternans, while AP prolongation occurs primarily due to an associated down regulation of K+ currents. Interestingly, they find that blocking SR Ca2+ leak restores contraction and relaxation function, but does not eliminate alternans completely.

Grandi et al. (2007) developed a model of CaMKII overexpression in the rabbit ventricular myocyte, which incorporates the functional effects of CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of LCCs, as well as INa and Ito1. This model shows that while CaMKII-mediated action on LCCs prolongs the AP, the combined effect of CaMKII on all three of the targets studied leads to AP shortening. While this study was primarily motivated by and focused on the functional role of CaMKII-mediated regulation of INa (see accompanying article in this series by Grandi and Herren), it clearly demonstrates that the multiple targets of CaMKII interact to produce net alterations of integrated cellular function which are difficult to predict from knowledge if its functional effects on isolated individual targets. Saucerman and Bers (2008) developed and incorporated models of CaM, CaMKII, and calcineurin (CaN) into the rabbit ventricular myocyte model of Shannon et al. (2004) in order to better understand the functional consequences of the different affinities of CaM for CaMKII and CaN during APs. The model predicts that the relatively high Ca2+ levels that are achieved in the cardiac dyad lead to a high degree of CaM activity which results in frequency-dependent CaMKII activation and constitutive CaN activation, whereas the lower Ca2+ levels in the cytosol only minimally activate CaM, which allows for gradual CaN activation, but no significant activation of CaMKII. The prediction that robust beat-to-beat oscillations of CaMKII activity occur in the dyad (i.e. in the vicinity of RyRs and LCCs) but not in the cytosol is a key factor that would influence the way in which local signaling mechanisms would be incorporated into models that followed that included detailed reconstruction of dyadic Ca2+ dynamics. In one such model, Soltis and Saucerman (2010) integrated dynamic CaMKII-dependent regulation of LCCs, RyRs, and PLB with models of cardiac ECC, CaMKII activation, and β-adrenergic activation of protein kinase A (PKA). In this model phosphorylation of all CaMKII substrates exhibits positive frequency dependence similar to that observed in experiments (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). However, both CaMKII activity and target protein phosphorylation levels adapt to changes in pacing rate with distinct kinetics (see Figure 2 of Soltis and Saucerman, 2010). CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation is relatively fast at LCCs, slower at RyRs, and very slow at PLB. Additionally, the model predicts a high degree of phosphorylation of LCCs in control conditions, but a moderate amount of phosphorylation of RyRs and PLB (e.g., PLB phosphorylation <10% at all frequencies). In addition, this study predicts a novel mechanism in which CaMKII and PKA synergize to form a positive feedback loop of CaMKII-Ca2+-CaMKII regeneration. Furthermore, this model predicts that CaMKII-mediated hyperphosphorylation of RyRs, which renders them leaky, may be a proarrhythmic trigger via induction of delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs). Recently, Morotti et al. (2014) modified the Soltis and Saucerman (2010) rabbit model to further investigate the arrhythmogenic role of another synergistic interaction in mouse ventricular myocytes. This synergism is that of the positive feedback loop of CaMKII-Na+-Ca2+-CaMKII in which CaMKII-dependent increases in intracellular Na+ level perturbs Ca2+ homeostasis and CaMKII activation. Simulation results from Morotti et al. (2014) demonstrate that the feedback between disrupted Na+ fluxes and CaMKII signaling is exaggerated when CaMKII is overexpressed. Under this condition, and upon an increase in intracellular Na+ concentration, the model predicts Ca2+ overload and enhancement of CaMKII activity which in turn increases spontaneous Ca2+ release events via an increase in RyR phosphorylation. This CaMKII-dependent hyperphosphorylation of RyRs exacerbates the associated electrophysiological instability as simulated by the occurrence of DADs (see Figure 7 of Morotti et al., 2014). In this model, the DADs do not occur when CaMKII target phosphorylation is clamped to basal levels.

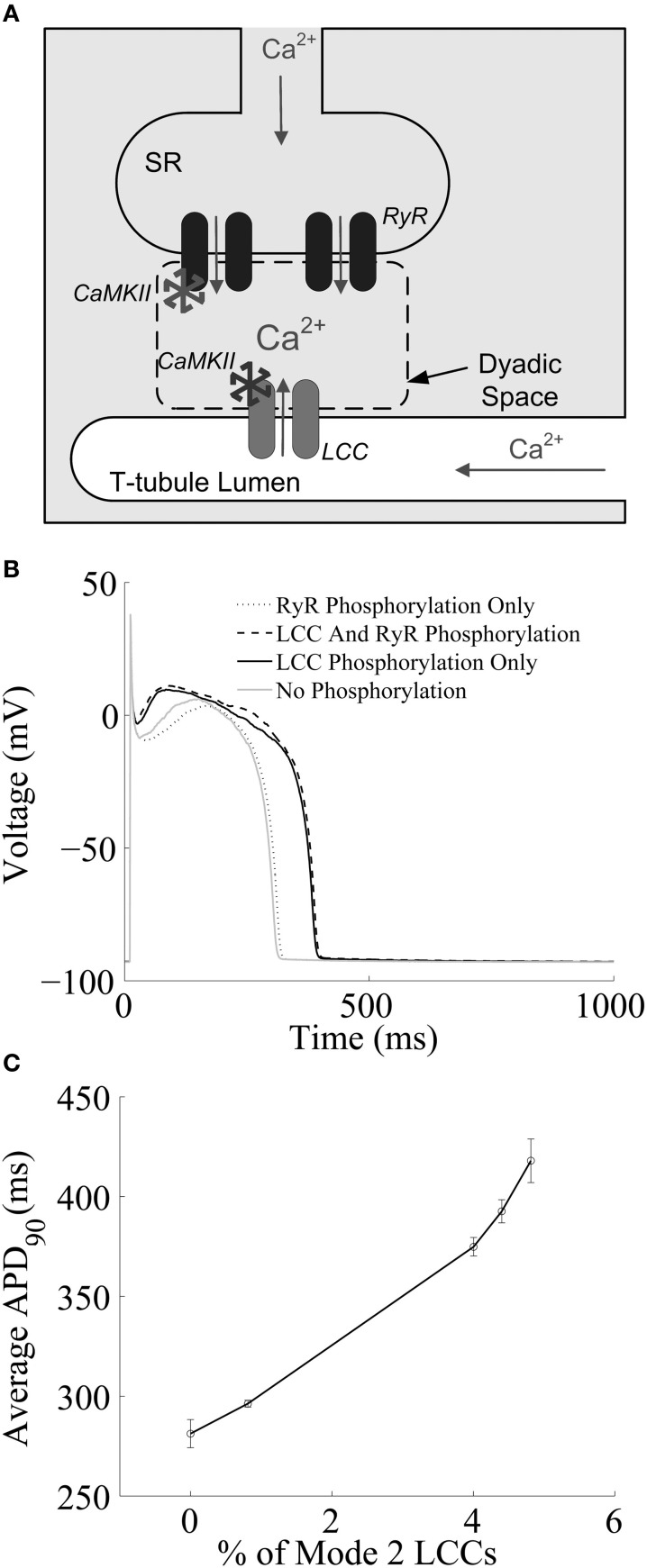

Recently, Hashambhoy et al. (2009) developed a biochemically and biophysically detailed model of CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of LCCs. The model includes descriptions of the dynamic interactions among CaMKII, LCCs, and phosphatases as a function of dyadic Ca2+ and CaM levels, and has been incorporated into an integrative model of the canine ventricular myocyte with stochastic simulation of LCC and RyR channel gating within a population of release sites based on the theory of local control of ECC (Greenstein and Winslow, 2002). A schematic representation of one such model Ca2+-release site is shown in Figure 1A. This CaMKII-LCC model is formed by the integration of three modules: a CaMKII activity model which reflects the different structural and functional states of the kinase based on the work of Hudmon and Schulman (2002) and Dupont et al. (2003), an LCC phosphorylation model derived from studies of facilitation in LCC mutants (Grueter et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2006), and a previously developed LCC gating model (Jafri et al., 1998; Greenstein and Winslow, 2002). In this model it is assumed that there is one 12-subunit CaMKII holoenzyme tethered to each LCC (Hudmon et al., 2005), each CaMKII monomer can transition among a variety of activity states (see Figure 2 of Hashambhoy et al., 2009), and CaMKII monomers can catalyze phosphorylation of individual LCCs. The LCC gating model reflects two forms of channel gating, mode 1 (normal activity) and mode 2 (high activity with long openings). In the model, LCC phosphorylation promotes transitions of LCCs from mode 1 to mode 2 gating, based on experimental observations with constitutively active CaMKII (Dzhura et al., 2000). This model demonstrates that these CaMKII-dependent shifts of LCC gating patterns into high activity gating modes may be the underlying mechanism of ICaL facilitation. In addition, the model predicts that this CaMKII-mediated shift in LCC gating leads to an apparent increase in the speed of both ICaL inactivation and recovery from inactivation, both of which are experimentally associated with ICaL facilitation, with no change to the underlying intrinsic LCC inactivation kinetics. Hashambhoy et al. (2010) further expanded this model to include CaMKII-dependent regulation of RyRs. In this model update, RyR phosphorylation is modeled as a function of dyadic CaMKII activity and it is assumed that RyR sensitivity to dyadic Ca2+ is increased upon phosphorylation, the degree to which is constrained by experimental measurements of Ca2+ spark frequency and steady state RyR phosphorylation (Guo et al., 2006). This study demonstrated that under physiological conditions, CaMKII phosphorylation of LCCs ultimately has a greater effect on ECC gain, RyR leak flux, and AP duration as compared with phosphorylation of RyRs (Figure 1B). AP duration at 90% repolarization (APD90) correlates well with a CaMKII-mediated shift in modal gating of LCCs (Figure 1C). A modest additional increase in LCC phosphorylation, and hence mode 2 gating, beyond that shown in Figure 1C leads to the appearance of early afterdepolarizations (EADs) in simulated APs (see Figure 5 of Hashambhoy et al., 2010). The results of these model analyses suggest that LCC phosphorylation sites may in fact prove to be a more effective target than those on the RyR for modulating diastolic RyR-mediated Ca2+ leak and preventing abnormal proarrhythmic cellular depolarization.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the cardiac dyad. Ca2+ ions pass through the LCC and enter the dyad, where they bind to RyRs, triggering CICR. The activity of each CaMKII monomer is a function of dyadic Ca2+ levels. Ca2+ ions released from the SR diffuse out of the dyad into the bulk myoplasm. (B) Simulated results from a 1-Hz AP-pacing protocol under different LCC and/or RyR phosphorylation conditions. (C) APD90 as a function of average LCC phosphorylation levels. Fully phosphorylated LCCs gate in mode 2, which exibit long-duration openings. (A) Reprinted with permission from Hashambhoy et al. (2009). Copyright 2009 Elsevier. (B,C) Reprinted with permission from Hashambhoy et al. (2010). Copyright 2010 Elsevier.

Models of oxidative CaMKII activation and regulation

The modeling studies described above focus on the role of CaMKII-mediated regulation of its targets via the classical Ca2+/CaM-dependent activation pathway which involves CaMKII autophosphorylation. Recently a novel mechanism for oxidative CaMKII activation was discovered in the heart (Erickson et al., 2008). This alternative oxidation-dependent pathway involves the oxidation of CaMKII at specific methionine residues, which has been shown to produce persistent kinase activity and increase the likelihood of arrhythmias (Xie et al., 2009; Wagner et al., 2011). These new findings implicate oxidative CaMKII activation as a putative mechanistic link between the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias (Erickson et al., 2011). Therefore, developing a quantitative understanding of the role of CaMKII oxidation in regulating cardiac ECC requires the integration of computational models that link cellular ROS and redox balance, CaMKII activity and function, ECC, and whole-cell electrophysiology. Such models will prove to be powerful tools for teasing out important mechanisms of arrhythmia in heart disease.

In one recent study, Christensen et al. (2009) developed a deterministic model of oxidative CaMKII activation based on their own experimental findings to study the role of this signaling pathway in the canine infarct border zone following myocardial infarction. A new simplified model of CaMKII activation was developed based on the work of Dupont et al. (2003), and incorporated into a model of a single cardiac fiber. Each myocyte within the fiber model was represented by the Hund et al. (2008) model, which as noted above, incorporates CaMKII effects on INa, ICaL, SR Ca2+ leak and uptake, as well as ion channel remodeling associated with the infarct border zone. Simulation results demonstrate that enhanced oxidative CaMKII activity is associated with reduced conduction velocity, increased refractory periods, and a greater likelihood of conduction block formation. Furthermore, CaMKII inhibition in the model improves conduction and reduces vulnerability to conduction block and reentry. The results of Christensen et al. (2009) are attributed primarily to CaMKII-mediated regulation of INa kinetics and availability. They note that CaMKII activation will also impact ECC proteins in ways that may promote arrhythmias, but these mechanisms were not explored in detail in this model.

Along these lines, Foteinou et al. (2013) have recently developed a novel stochastic model of CaMKII activation (Figure 2A) that reflects the functional properties of the cardiac isoform including both the canonical phosphorylation-dependent activation pathway and the newly identified oxidation-dependent pathway. This model builds upon the work of Hashambhoy et al. (2010, 2011) in order to incorporate recent experimental data for CaM affinity and autophosphorylation/oxidation rates measured specifically for the cardiac isoform of CaMKII (Gaertner et al., 2004; Erickson et al., 2008). Predicated upon this, the authors implemented the four-state deterministic activation model of Chiba et al. (2008) within a stochastic framework that is constrained by the geometry of the CaMKII holoenzyme. This was accomplished by restricting CaMKII autophoshorylation events to occur only between adjacent CaMKII subunits. The stochastic activation model was further modified by including oxidized active states in addition to a Ca2+/CaM-bound active state, an autophosphorylated Ca2+/CaM-bound state, and an autophosphorylated Ca2+/CaM-dissociated state (i.e., an autonomous active state). Following incorporation into the canine cardiac myocyte model (Hashambhoy et al., 2011), Foteinou et al. (2013) obtain steady state APs at a pacing cycle length (PCL) of 2 s as illustrated in Figure 2B. This model predicts increased likelihood of EADs under this protocol upon increased oxidative stress (application of 200 μM H2O2, which is at the high end of pathophysiological levels), as shown in Figure 2C. Notably, the model simulates no EADs in the presence of ROS at a PCL of 1 s, which is consistent with the experimentally measured rate-dependence of EADs in the presence of 200 μM H2O2 (Zhao et al., 2012). The model predicts that EADs result from both enhanced CaMKII-dependent shifts of LCCs into highly active mode 2 gating and a progressively increased late component of Na+ current (INaL). The simulated increase in ICaL via oxidized CaMKII corroborates the experimental findings of Song et al. (2010) who demonstrated that oxidative CaMKII activation is involved in the regulation of LCCs. In particular, the in silico model of H2O2 exposure discussed here predicts that the fraction of LCCs gaiting in mode 2 will shift from 5% in control (absence of ROS) to 7% upon this increase in ROS. Using this model, the simulated diastolic RyR leak also increases in response to oxidative stress (~44%) primarily as an indirect consequence of increased Ca2+ influx via LCCs. Wagner et al. (2011) recently observed a ~15-fold H2O2-mediated increase in SR Ca2+ leak, which is far greater than that produced in this model (<2-fold). They, however, provide additional evidence indicating that their observed increase in Ca2+ leak does not require the presence of CaMKII, suggesting an important role for CaMKII-independent mechanisms of ROS-mediated alteration of cardiac ECC as well.

Figure 2.

(A) State diagram of the stochastic CaMKII activation model of Foteinou et al. (2013). Prior to the introduction of Ca2+/CaM, all of the CaMKII subunits are in the inactive form (state I). Activation occurs upon binding of Ca2+/CaM (state B), autophosphorylation (state P), and oxidation (state OxB). Autonomous active states (Ca2+/CaM-unbound) can be either autophosphorylated (state A) or oxidized (state OxA). The model also includes an active state that is both oxidized and phosphorylated (state OxP). (B) Simulated steady state APs under control conditions (0 μM H2O2). (C) Simulated APs, some of which exhibit EADs, under conditions of elevated oxidant stress (200 μM H2O2). Simulated APs are from a 2 s PCL pacing protocol (ensemble of 12500 calcium release units). For each condition, results for 10 consecutive APs following an initial 10 s of pacing are shown.

As these ROS-mediated effects need to be further examined, future studies will focus on establishing quantitative links between cellular ROS and redox balance, CaMKII activity and function, ECC, and whole-cell electrophysiology. Recently, Gauthier et al. (2013a,b) developed mechanistic models of ROS production and scavenging to investigate how these two competing processes control ROS levels in cardiac mitochondria. Simulations confirm the hypothesis that mitochondrial Ca2+ mismanagement leads to decreased scavenging resources and accounts for ROS overflow as is believed to occur in heart failure (Hill and Singal, 1996). Notably, the ROS regulation module of Gauthier et al. (2013b) enables its use in larger scale heart models designed to simulate and study how mitochondrial ROS and the functional consequences of its accumulation, such as CaMKII oxidation, regulate cellular physiological function, AP properties, and arrhythmogenesis.

Conclusion

Integrative modeling of cardiac ECC, cell signaling, and myocyte physiology has played a critical role in revealing mechanistic insights across a range of biological scales. With respect to CaMKII function at the smallest scale, models have shed light on how Ca2+ ions, CaM, CaMKII, LCCs, and RyRs interact in the cardiac dyadic junction both at rest and during triggered ECC events. On an intermediate scale, models have predicted the consequences of normal and abnormal CaMKII signaling on whole-cell Ca2+ cycling, effects of ROS imbalance, AP shape, and the generation of cellular arrhythmias such as EADs. Incorporation of these cellular models into higher scale tissue simulations has provided important insight into the relationship between CaMKII function, electrical wave conduction velocity, and the emergence of arrhythmogenic substrates in diseased tissue. The continuum of biological scales spanned by these models allows for the development of multiscale approaches whereby we can predict and understand the emergence of macroscale phenotypes as a consequence of CaMKII-mediated molecular signaling events. A great deal of evidence now implicates CaMKII as a nexus point linking heart failure and arrhythmias (Swaminathan et al., 2012), identifying it as a prime target for antiarrhythmic therapies (Fischer et al., 2013). Despite this growing body of evidence, the modeling studies presented here demonstrate that it remains difficult to identify which of the many CaMKII target proteins are primarily responsible for the functional changes that increase the likelihood of arrhythmia development. Some studies (Hund et al., 2008; Soltis and Saucerman, 2010; Zang et al., 2013; Morotti et al., 2014) identify phosphorylation of RyRs, which leads to elevated SR Ca2+ leak and/or increased likelihood of spontaneous Ca2+ release events and DADs, as the key mechanism underlying arrhythmogenesis. Others (Hashambhoy et al., 2010; Foteinou et al., 2013) predict that LCC phosphorylation, which leads to elevated channel open probability via high activity gating, plays the predominant role by altering whole cell Ca2+ levels and AP properties, including the appearance of EADs. These mechanisms may co-exist in heart failure, and it is likely that both play an important role. Moreover, CaMKII modulation of other targets such as PLB, INa, and K+ currents, many of which have been incorporated into the above cell models, adds additional layers of complexity to the task of interpreting and predicting the mechanisms by which CaMKII signaling alters cardiac function in health and disease. As a result of the breadth and diversity of CaMKII targets, strategies that involve broad inhibition of CaMKII activity will impact and alter the function of many cellular subsystems, with complex consequences that may not all be beneficial. As mathematical models of CaMKII signaling in the cardiac dyad and beyond are further developed, they will play a key role in identifying target-specific therapeutic strategies for improving myocardial function and reducing arrhythmias.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL087345, HL105239, and HL105216.

References

- Anderson M. E., Braun A. P., Schulman H., Premack B. A. (1994). Multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase mediates Ca(2+)-induced enhancement of the L-type Ca2+ current in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 75, 854–861 10.1161/01.RES.75.5.854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley D., Jayasinghe I. D., Lam L., Rossberger S., Cannell M. B., Soeller C. (2009). Optical single-channel resolution imaging of the ryanodine receptor distribution in rat cardiac myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 22275–22280 10.1073/pnas.0908971106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers D. M. (2001). Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. Boston, MA: Kluwer; 10.1007/978-94-010-0658-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla U. S., Iyengar R. (1999). Emergent properties of networks of biological signaling pathways. Science 283, 381–387 10.1126/science.283.5400.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko V. E., Szigeti G. P., Bett G. C., Kim S. J., Rasmusson R. L. (2004). Computer model of action potential of mouse ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H1378–H1403 10.1152/ajpheart.00185.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Lederer W. J., Cannell M. B. (1993). Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science 262, 740–744 10.1126/science.8235594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba H., Schneider N. S., Matsuoka S., Noma A. (2008). A simulation study on the activation of cardiac CaMKII delta-isoform and its regulation by phosphatases. Biophys. J. 95, 2139–2149 10.1529/biophysj.107.118505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M. D., Dun W., Boyden P. A., Anderson M. E., Mohler P. J., Hund T. J. (2009). Oxidized calmodulin kinase II regulates conduction following myocardial infarction: a computational analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5:e1000583 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie S., Loughrey C. M., Craig M. A., Smith G. L. (2004). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIdelta associates with the ryanodine receptor complex and regulates channel function in rabbit heart. Biochem. J. 377, 357–366 10.1042/BJ20031043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker K. F., Heijman J., Silva J. R., Hund T. J., Rudy Y. (2009). Properties and ionic mechanisms of action potential adaptation, restitution, and accommodation in canine epicardium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 296, H1017–H1026 10.1152/ajpheart.01216.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck P., Schulman H. (1998). Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science 279, 227–230 10.1126/science.279.5348.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont G., Houart G., De Koninck P. (2003). Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations: a simple model. Cell Calcium 34, 485–497 10.1016/S0143-4160(03)00152-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhura I., Wu Y., Colbran R. J., Balser J. R., Anderson M. E. (2000). Calmodulin kinase determines calcium-dependent facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 173–177 10.1038/35004052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson J. R., He B. J., Grumbach I. M., Anderson M. E. (2011). CaMKII in the cardiovascular system: sensing redox states. Physiol. Rev. 91, 889–915 10.1152/physrev.00018.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson J. R., Joiner M. L., Guan X., Kutschke W., Yang J., Oddis C. V., et al. (2008). A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell 133, 462–474 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T. H., Neef S., Maier L. S. (2013). The Ca-calmodulin dependent kinase II: a promising target for future antiarrhythmic therapies? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 58, 182–187 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foteinou P. T., Greenstein J. L., Winslow R. L. (2013). A novel stochastic model of cardiac CaMKII activation. Biomed. Eng. Soc. P-Fri-A-35 [Google Scholar]

- Franzini-Armstrong C., Protasi F., Ramesh V. (1999). Shape, size, and distribution of Ca(2+) release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys. J. 77, 1528–1539 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner T. R., Kolodziej S. J., Wang D., Kobayashi R., Koomen J. M., Stoops J. K., et al. (2004). Comparative analyses of the three-dimensional structures and enzymatic properties of alpha, beta, gamma and delta isoforms of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12484–12494 10.1074/jbc.M313597200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier L. D., Greenstein J. L., Cortassa S., O'rourke B., Winslow R. L. (2013a). A computational model of reactive oxygen species and redox balance in cardiac mitochondria. Biophys. J. 105, 1045–1056 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier L. D., Greenstein J. L., O'rourke B., Winslow R. L. (2013b). An integrated mitochondrial ROS production and scavenging model: implications for heart failure. Biophys. J. 105, 2832–2842 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi E., Puglisi J. L., Wagner S., Maier L. S., Severi S., Bers D. M. (2007). Simulation of Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II on rabbit ventricular myocyte ion currents and action potentials. Biophys. J. 93, 3835–3847 10.1529/biophysj.107.114868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein J. L., Winslow R. L. (2002). An integrative model of the cardiac ventricular myocyte incorporating local control of Ca2+ release. Biophys. J. 83, 2918–2945 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75301-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter C. E., Abiria S. A., Dzhura I., Wu Y., Ham A. J., Mohler P. J., et al. (2006). L-type Ca2+ channel facilitation mediated by phosphorylation of the beta subunit by CaMKII. Mol. Cell 23, 641–650 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T., Zhang T., Mestril R., Bers D. M. (2006). Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation of ryanodine receptor does affect calcium sparks in mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 99, 398–406 10.1161/01.RES.0000236756.06252.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson P. I., Meyer T., Stryer L., Schulman H. (1994). Dual role of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of multifunctional CaM kinase may underlie decoding of calcium signals. Neuron 12, 943–956 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90306-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashambhoy Y. L., Greenstein J. L., Winslow R. L. (2010). Role of CaMKII in RyR leak, EC coupling and action potential duration: a computational model. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 49, 617–624 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashambhoy Y. L., Winslow R. L., Greenstein J. L. (2009). CaMKII-induced shift in modal gating explains L-type Ca(2+) current facilitation: a modeling study. Biophys. J. 96, 1770–1785 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashambhoy Y. L., Winslow R. L., Greenstein J. L. (2011). CaMKII-dependent activation of late INa contributes to cellular arrhythmia in a model of the cardiac myocyte. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2011, 4665–4668 10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6091155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Martone M. E., Yu Z., Thor A., Doi M., Holst M. J., et al. (2009). Three-dimensional electron microscopy reveals new details of membrane systems for Ca2+ signaling in the heart. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1005–1013 10.1242/jcs.028175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M. F., Singal P. K. (1996). Antioxidant and oxidative stress changes during heart failure subsequent to myocardial infarction in rats. Am. J. Pathol. 148, 291–300 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon A., Schulman H. (2002). Structure-function of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 364, 593–611 10.1042/BJ20020228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon A., Schulman H., Kim J., Maltez J. M., Tsien R. W., Pitt G. S. (2005). CaMKII tethers to L-type Ca2+ channels, establishing a local and dedicated integrator of Ca2+ signals for facilitation. J. Cell Biol. 171, 537–547 10.1083/jcb.200505155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hund T. J., Decker K. F., Kanter E., Mohler P. J., Boyden P. A., Schuessler R. B., et al. (2008). Role of activated CaMKII in abnormal calcium homeostasis and I(Na) remodeling after myocardial infarction: insights from mathematical modeling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 45, 420–428 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hund T. J., Rudy Y. (2004). Rate dependence and regulation of action potential and calcium transient in a canine cardiac ventricular cell model. Circulation 110, 3168–3174 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147231.69595.D3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iribe G., Kohl P., Noble D. (2006). Modulatory effect of calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ handling and interval-force relations: a modelling study. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 364, 1107–1133 10.1098/rsta.2006.1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafri M. S., Rice J. J., Winslow R. L. (1998). Cardiac Ca2+ dynamics: the roles of ryanodine receptor adaptation and sarcoplasmic reticulum load. Biophys. J. 74, 1149–1168 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77832-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhaas M., Zhang T., Seidler T., Zibrova D., Dybkova N., Steen A., et al. (2006). Increased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak but unaltered contractility by acute CaMKII overexpression in isolated rabbit cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 98, 235–244 10.1161/01.RES.0000200739.90811.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivumaki J. T., Korhonen T., Takalo J., Weckstrom M., Tavi P. (2009). Regulation of excitation-contraction coupling in mouse cardiac myocytes: integrative analysis with mathematical modelling. BMC Physiol. 9:16 10.1186/1472-6793-9-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. S., Karl R., Moosmang S., Lenhardt P., Klugbauer N., Hofmann F., et al. (2006). Calmodulin kinase II is involved in voltage-dependent facilitation of the L-type Cav1.2 calcium channel: identification of the phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25560–25567 10.1074/jbc.M508661200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livshitz L. M., Rudy Y. (2007). Regulation of Ca2+ and electrical alternans in cardiac myocytes: role of CAMKII and repolarizing currents. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H2854–H2866 10.1152/ajpheart.01347.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokuta A. J., Rogers T. B., Lederer W. J., Valdivia H. H. (1995). Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptors of swine and rabbit by a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation mechanism. J. Physiol. 487(Pt 3), 609–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C. H., Rudy Y. (1994). A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. I. Simulations of ionic currents and concentration changes. Circ. Res. 74, 1071–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier L. S. (2005). CaMKIIdelta overexpression in hypertrophy and heart failure: cellular consequences for excitation-contraction coupling. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 38, 1293–1302 10.1590/S0100-879X2005000900002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier L. S., Bers D. M. (2007). Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) in excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 73, 631–640 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier L. S., Zhang T., Chen L., Desantiago J., Brown J. H., Bers D. M. (2003). Transgenic CaMKIIdeltaC overexpression uniquely alters cardiac myocyte Ca2+ handling: reduced SR Ca2+ load and activated SR Ca2+ release. Circ. Res. 92, 904–911 10.1161/01.RES.0000069685.20258.F1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T., Hanson P. I., Stryer L., Schulman H. (1992). Calmodulin trapping by calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Science 256, 1199–1202 10.1126/science.256.5060.1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morotti S., Edwards A. G., McCulloch A. D., Bers D. M., Grandi E. (2014). A novel computational model of mouse myocyte electrophysiology to assess the synergy between Na+ loading and CaMKII. J. Physiol. 592(Pt 6), 1181–1197 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.266676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble D., Noble S. J., Bett G. C., Earm Y. E., Ho W. K., So I. K. (1991). The role of sodium-calcium exchange during the cardiac action potential. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 639, 334–353 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb17323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'hara T., Virag L., Varro A., Rudy Y. (2011). Simulation of the undiseased human cardiac ventricular action potential: model formulation and experimental validation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7:e1002061 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice J. J., Winslow R. L., Hunter W. C. (1999). Comparison of putative cooperative mechanisms in cardiac muscle: length dependence and dynamic responses. Am. J. Physiol. 276, H1734–H1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokita A. G., Anderson M. E. (2012). New therapeutic targets in cardiology: arrhythmias and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII). Circulation 126, 2125–2139 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.124990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucerman J. J., Bers D. M. (2008). Calmodulin mediates differential sensitivity of CaMKII and calcineurin to local Ca2+ in cardiac myocytes. Biophys. J. 95, 4597–4612 10.1529/biophysj.108.128728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon T. R., Wang F., Puglisi J., Weber C., Bers D. M. (2004). A mathematical treatment of integrated Ca dynamics within the ventricular myocyte. Biophys. J. 87, 3351–3371 10.1529/biophysj.104.047449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeller C., Cannell M. B. (1999). Examination of the transverse tubular system in living cardiac rat myocytes by 2-photon microscopy and digital image-processing techniques. Circ. Res. 84, 266–275 10.1161/01.RES.84.3.266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeller C., Cannell M. B. (2004). Analysing cardiac excitation-contraction coupling with mathematical models of local control. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 85, 141–162 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis A. R., Saucerman J. J. (2010). Synergy between CaMKII substrates and beta-adrenergic signaling in regulation of cardiac myocyte Ca(2+) handling. Biophys. J. 99, 2038–2047 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. H., Cho H., Ryu S. Y., Yoon J. Y., Park S. H., Noh C. I., et al. (2010). L-type Ca(2+) channel facilitation mediated by H(2)O(2)-induced activation of CaMKII in rat ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 773–780 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern M. D. (1992). Theory of excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 63, 497–517 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81615-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan P. D., Purohit A., Hund T. J., Anderson M. E. (2012). Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: linking heart failure and arrhythmias. Circ. Res. 110, 1661–1677 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S., Ruff H. M., Weber S. L., Bellmann S., Sowa T., Schulte T., et al. (2011). Reactive oxygen species-activated Ca/calmodulin kinase IIdelta is required for late I(Na) augmentation leading to cellular Na and Ca overload. Circ. Res. 108, 555–565 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens X. H., Lehnart S. E., Reiken S. R., Marks A. R. (2004). Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ. Res. 94, e61–e70 10.1161/01.RES.0000125626.33738.E2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R. P., Cheng H., Lederer W. J., Suzuki T., Lakatta E. G. (1994). Dual regulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II activity by membrane voltage and by calcium influx. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 9659–9663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L. H., Chen F., Karagueuzian H. S., Weiss J. N. (2009). Oxidative-stress-induced afterdepolarizations and calmodulin kinase II signaling. Circ. Res. 104, 79–86 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.183475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W., Bers D. M. (1994). Ca-dependent facilitation of cardiac Ca current is due to Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Am. J. Physiol. 267, H982–H993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang Y., Dai L., Zhan H., Dou J., Xia L., Zhang H. (2013). Theoretical investigation of the mechanism of heart failure using a canine ventricular cell model: especially the role of up-regulated CaMKII and SR Ca(2+) leak. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 56, 34–43 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z., Wen H., Fefelova N., Allen C., Baba A., Matsuda T., et al. (2012). Revisiting the ionic mechanisms of early afterdepolarizations in cardiomyocytes: predominant by Ca waves or Ca currents? Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302, H1636–H1644 10.1152/ajpheart.00742.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]