Abstract

To minimize risk of spinal cord injury, airway management providers must understand the anatomic and functional relationship between the airway, cervical column, and spinal cord. Patients with known or suspected cervical spine injury may require emergent intubation for airway protection and ventilatory support or elective intubation for surgery with or without rigid neck stabilization (i.e., halo). To provide safe and efficient care in these patients, practitioners must identify high-risk patients, be comfortable with available methods of airway adjuncts, and know how airway maneuvers, neck stabilization, and positioning affect the cervical spine. This review discusses the risks and benefits of various airway management strategies as well as specific concerns that affect patients with known or suspected cervical spine injury.

Keywords: Anesthesia, intubation, spinal cord injury, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Spinal cord injury can be a devastating consequence of cervical spine injury from trauma or disease. It is estimated cervical spine injury affects 2-5% of blunt trauma patients,[1] and this risk rises dramatically in the presence of head or facial injury, decreased level of consciousness, or focal neurologic deficit.[2,3] Patients with possible cervical spine injury may require urgent or emergent airway intervention for airway protection, hypoxia, hypoventilation, or hypotension that is a direct consequence of spinal cord injury or instead related to head or other bodily injury. Patients with known cervical spine injury or disease may also be encountered in elective situations such as planned cervical spine surgery. Providers at all stages, including prehospital, emergency department, anesthesiology, and intensive care unit, should be familiar with techniques to minimize the risk of spinal cord injury during airway management.

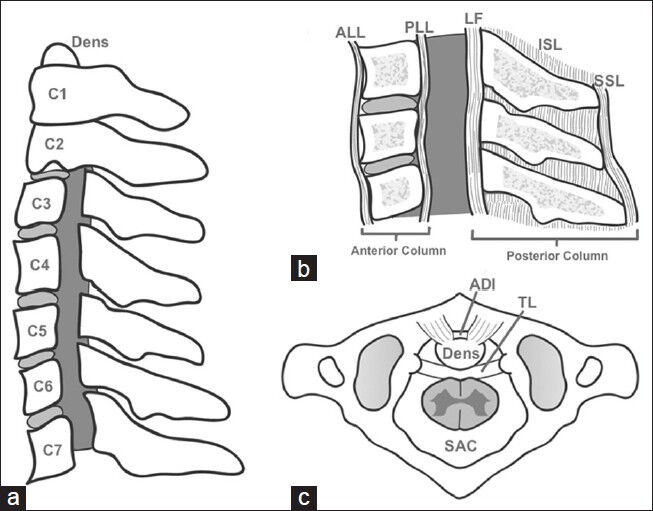

Cervical spine anatomy

The cervical spine is composed of seven vertebra and their associated ligaments and intervertebral discs [Figure 1]. The two uppermost cervical vertebra, C1 (atlas) and C2 (axis), support the weight and mobility of the skull (occiput) and form the atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joints. The ligaments of the cervical spine are commonly divided into two columns. The posterior column provides stability during flexion and includes the supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, and the ligamentum flavum. The anterior column, in contrast, provides stability during extension and includes the posterior longitudinal ligament, the anterior longitudinal ligament, and the three ligaments that secure the dens (odontoid process) of C2 to the anterior arch of C1. These include the apical ligament, the occipital and atlantal portions of the alar ligament, and the transverse ligament. These three ligaments normally limit translational movement between the dens and atlas arch to less than 3 mm. If the transverse ligament is damaged translation approaches 5 mm and if all three are damaged, such as in trauma or severe rheumatoid arthritis, translation has been estimated up to 10 mm.[4]

Figure 1.

Cervical Spine Anatomy. (a) Lateral view of seven cervical vertebra, laminae and pedicles removed to show spinal cord space (gray), (b) Ligaments forming the anterior and posterior columns shown in lateral cross section, ALL: Anterior longitudinal ligament, PLL: Posterior longitudinal ligament, LF: Ligamentum flavum, ISL: Interspinous ligament, SSL: Supraspinous ligament, (c) Superior view of first on second cervical vertebra and the transverse ligament (TL), which normally limits translation and the atlas-dens interval (ADI)

Cervical spine mechanics

Normally the bones and ligaments of the cervical spine serve to protect the spinal cord from damage. In fact, the definition of a stable spine is, “the ability of the spine to limit its pattern of displacement under physiologic loads so as not to allow damage or irritation of the spinal cord or nerve roots.”[5] If the spinal canal becomes too narrow, spinal cord compromise occurs, if persistent, spinal cord injury results. At the level of C1, if the spinal canal is appreciated in a sagittal plane, the anterior one third is occupied by the dens, approximately the middle third is spinal cord, and the posterior third is deemed the space available for the spinal cord. This space provides a buffer to protect the spinal cord from compromise and injury should narrowing of spinal canal occur from vertebral subluxation or instability, disc impingement, spinal cord swelling, etc., The spinal canal and the space available for the spinal cord are dynamic spaces of relatively fixed volume with mechanics that are influenced by the Poisson Effect.[6]

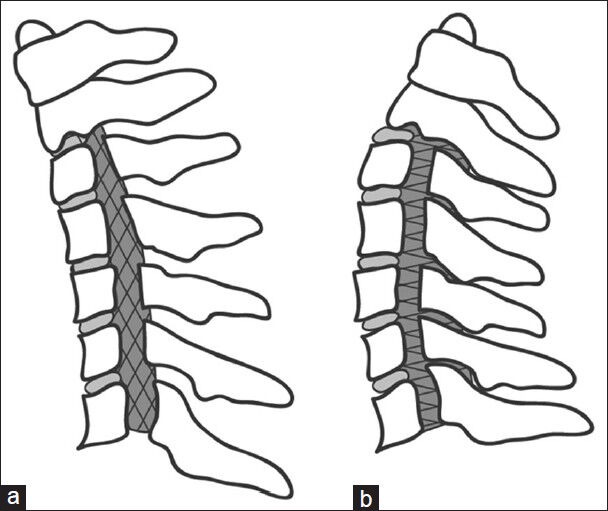

This concept, which can be understood by thinking of a Chinese-finger trap, dictates that if a column of fixed volume is compressed its cross-sectional area will increase. Conversely, if it is stretched, its cross-sectional area will decrease. Now, picturing vertebral bodies as the axis during flexion and extension, one can apply the Poisson Effect to the spinal column [Figure 2]. During neck flexion, the spinal cord and canal are stretched and can be subjected to further narrowing of the space available for the cord by posterior impingement of a damaged intervertebral disc, osteophyte, or subluxed vertebral body. Conversely during neck extension, the length of the spinal cord and canal is decreased, which increases the cross sectional area of each. Initially it would seem that extending the neck and increasing the area of the space available for the spinal cord would be favorable, however, the opposite has actually been shown to be true by Ching et al.[7] Ligamentum flavum bulge caused by ligament laxity resulting from reduced vertebral body height has been proposed for the possible mechanism for the extension injury. This unfavorable ratio of spinal cord to space available for the spinal cord is likely explained by the fact that the spinal cord is also a column of relatively fixed volume governed by the Poisson Effect. As both extremes of movement can be implicated in narrowing the space available for the spinal cord, it is important to realize that excessive flexion or extension during airway management or surgical positioning, especially prone positioning, which risks extreme extension, can cause compromise or even injury to the spinal cord. For this reason, “neutral positioning” is encouraged. Unfortunately, there is not a universal definition of neutral positioning. We suggest being very mindful about insisting on as neutral positioning as possible, eliciting input from patients about neutral positioning, and, when available, using and documenting electrophysiologic measurements of evoked potentials after positioning.

Figure 2.

The Poisson Effect Applied to the Cervical Spine (a) During neck flexion, the axis of the cervical spine is the vertebral bodies, so both the spinal cord and space available for the spinal cord are stretched and narrowed (gray hatch marks), (b) During neck extension, both the spinal cord and space available for the spinal cord are compressed and widened

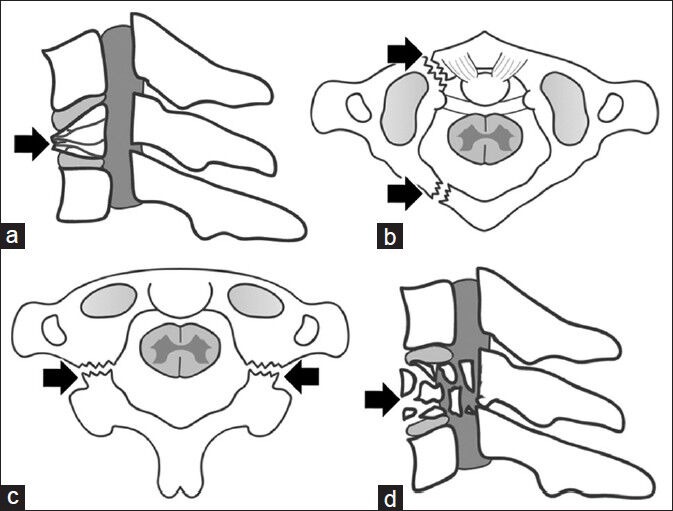

Cervical spine injury types

Providers caring for trauma patients must have a basic understanding of cervical spine injury types and mechanisms. Types of injury include hyperflexion, hyperextension, compression, and clinically insignificant injuries [Figure 3]. Hyperflexion injuries involve distraction, or overstretching, of the posterior column and can range from mild, usually stable injuries (i.e., wedge fractures) to severe, usually unstable injuries (i.e., facet joint fractures). Hyperextension injuries involve distraction of the anterior column. They include the unstable spinal cord compressing “diving injury” (fracture of pedicles, laminae, or lateral vertebral masses), “Jefferson fracture” (fracture of C1 anterior and posterior arches), and the unstable but decompressed “Hangman's fracture” (fracture of C2 pedicles). Compression injuries, including burst fractures, are relatively stable but can damage the spinal cord with retropulsed bone or disc fragments.

Figure 3.

Cervical Spine Injury Types (a) Hyperflexion leading a vertebral body wedge fracture, (b) Hyperflexion leading to a “Jefferson” fracture of C1 anterior and posterior arches, (c) Hyperflexion leading to “Hangman's” fracture of C2 pedicles, (d) Compression injuries leading to a vertebral body burst fractures and retropulsed bone fragments

Direct injury to the spinal cord is just one of several spinal cord injury mechanisms. It is defined as primary injury, and the only treatment option is prevention. Both the anterior and posterior spinal arteries arise from the vertebral arteries in the neck and descend from the base of the skull to supply spinal cord blood flow. There are also various radicular branches off the thoracic and abdominal aorta that provide segmental contributions. Recent animal studies have shown that segmental arteries give rise not only to the anterior spinal artery, but also to an extensive paraspinous network feeding the erector spinae, iliopsoas, and associated muscles. Spinal cord and paraspinous muscular networks are all interconnected, with multiple longitudinal arterial anastomoses along the vertebral column. Networks also receive input from the subclavian, hypogastric, and iliac arteries. This extensive blood supply was recently defined as the collateral network concept.[8]

Immediately following the primary injury, a cascade of secondary processes (secondary injury) in the injured tissue take place and include hypotension and hypoxemia-related ischemia, disrupted blood flow, loss of autoregulation, lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, acidification, excessive release of excitatory amino acids, inflammation, and gene-related events. Extent and duration of secondary injury directly relate to outcome. One study of ischemic spinal cord injury in a dog model found that hind limb function and evoked potentials were recoverable after 30 minutes of ischemia but not after 180 minutes.[9] Preservation or reduction of the secondary spinal cord injury leads to substantial clinical benefits. Every effort, therefore, should be made to maintain spinal cord perfusion by aggressively treating hypoxia and hypotension, with maintenance of mean arterial pressure at 85-90 mmHg for the first 7 days.[10] An additional mechanism of damage to the spinal cord is at the cellular level and involves the apoptosis cascade, which may be initiated at the time of injury, continue for several days postinjury, and may be amenable to surgical or medical intervention.

Cervical spine movement during intubation

With the anatomic proximity of airway structures to the cervical spine, it follows that the spine and spinal cord can be significantly displaced during airway intervention and positioning. Sniffing position, traditionally used during tracheal intubation, involves near-full extension of the atlanto-occipito and atlanto-axial joints and flexion of the lower cervical spine. The clinical relevance of this is unknown despite many studies in alive and cadaveric models of normal and injured cervical spines. This uncertainty persists because most studies have been small and underpowered, every cervical spine injury is somewhat unique, and there is no standard of measurement. Some studies have used static X-rays while others have used dynamic fluoroscopy, but there is even further disagreement about what is important in terms of absolute or relative displacement, or if focus should be on motion segments of two or three vertebra versus the whole cervical spine. These questions have been difficult to answer, and are likely to remain unanswered, because it would be unethical to subject potential cervical spine and spinal cord injury patients to a double-blind placebo controlled study. Two studies, however, are worth mention from a practical standpoint.

One, by Hauswald et al., which used cinefluoroscopy to measure mean maximum cervical spine displacement during airway manipulation in eight human traumatic arrest victims within 40 minutes of death. They found that mask ventilation caused the most displacement (2.93 mm), followed by oral intubation over a lighted stylette (1.65 mm), oral intubation (1.51 mm), whereas nasal intubation caused the least displacement (1.20 mm).[11] When Sawin et al. studied movement of the cervical spine during intubation in 10 nontrauma patients, they found that laryngoscope insertion caused minimal movement, blade elevation caused significant extension at all motion segments, especially at the atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joints, and intubation caused a very small amount of additional rotation.[12]

Risk stratification for cervical spine injury

Given the devastating nature of spinal cord injury, it is essential for providers to risk stratify and identify patients at high risk. A commonly quoted study by Crosby et al., estimates that 2-5% of blunt trauma patients have a cervical spine injury.[1] Demetriades et al. found a correlation between Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and cervical spine injury.[2] The incidence of spinal cord injury in patients with a GCS of 13-15 was only 1.4% compared with those with GCS 9-12 (6.8%) and GCS ≤ 8 (10.2%). Hackl et al. calculated odds ratios (OR) of cervical spine injury in the presence of other clinical findings and found an association between cervical spine injury and severe head injury (OR 8.5), persistent unconsciousness (OR 14), and focal neurologic deficit (OR 58).[3] While it is important to identify high risk patients, standard of care is immobilization until cervical spine injury is ruled out despite a Cochrane review by Kwan et al. in 2001 that did not find conclusive evidence of improved outcomes with neck immobilization.[10,13]

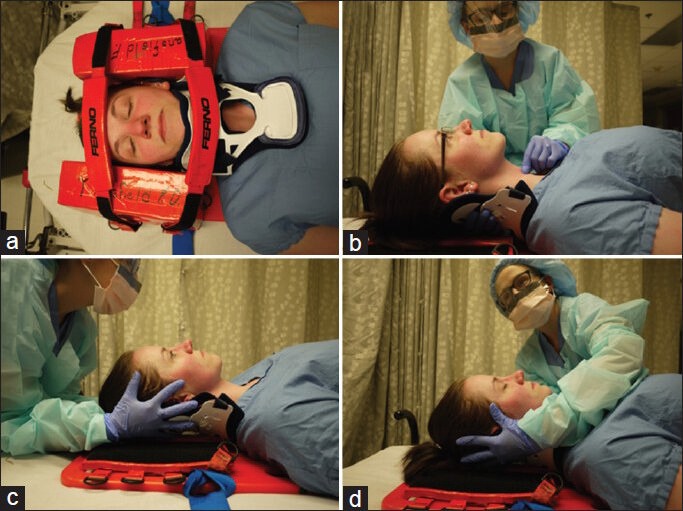

Neck immobilization

The neck should be immobilized in a natural position using collars, manual inline stabilization, hardboard with sandbags, and traction pins [Figure 4]. Nontraumatic spinal cord deformities should be considered such as ankylosing spondylitis, which may require additional padding under the head. Providers must be familiar with the various methods of immobilization and their implications for airway management. The gold standard for neck immobilization is the combined use of a hardboard, collar, sandbags, and tape or straps. This is used primarily during the prehospital transfers and can limit movement to 5% of the normal range. Unfortunately, this type of immobilization carries a high risk of pressure injury and severely limits the view attained on laryngoscopy. A study by Heath found that a majority of people, 64%, had Grade III or IV views on laryngoscopy while immobilized with a hardboard-collar-sandbag-tape combination.[14]

Figure 4.

Neck Maneuvers During Airway Management. (a) Neck stabilization using sandbag-collar-tape on hardboard for pre-hospital care, (b) Cricoid pressure application with anterior half of hard cervical collar removed and other hand behind posterior cervical collar, (c) Manual in-line stabilization from the head of bed, with anterior cervical collar removed and hands cradling occiput and mastoid process, (d) Manual in-line stabilization from side of bed to facilitate airway intervention from head of bed

Semirigid collars

Podolsky et al. found that hard Philadelphia collars were better than soft collars but not as good as the spine board-sandbag-tape-Philadelphia collar combination at restricting motion in volunteers asked to flex, extend, rotate, and laterally bend while lying supine.[15] Bednar published findings in a cadaver model of anterior and posterior column that found semirigid collars do not limit pathologic displacement and can actually increase cervical motion, possibly by acting as a lever.[16] Despite these findings, probably for lack of a convenient and suitable alternative, semirigid collars are still commonly used and their implications for airway management and positioning should be understood. One important point about hard collars is that they severely limit mouth opening. Goutcher measured average inter-incisor distance in volunteers before (41 mm) and after (26-29 mm) application of a hard plastic collar. Of note, upwards of 20% of participants had a mouth opening less than or equal to 20 mm.[17]

In addition, two recent studies performed on cadaveric models further highlight the limitations of cervical collar placement. In the first study, Prasarn et al., showed that even the application and removal of cervical collars can be associated with cervical displacement and suggested that collars should be placed and removed with in-line stabilization.[18] In a second cadaveric study, Horodyski et al. showed that while cervical collar placement is more advantageous, which no immobilization, neither one- or two-piece collars were very effective reducing segmental motion in the stable or unstable cervical spines, with significantly worse performance in the unstable condition.[19] Taken as a whole, the current literature emphasizes manual in-line stabilization and great vigilance in handling the patient with potential cervical spine injury, with cervical collar placement being only one piece of the management. In addition, the demonstration of the limitations of cervical collar placement shows the need for further research in immobilization techniques for the patient with a potentially injured cervical spine.

Manual inline stabilization

As limited mouth opening clearly effects orotracheal intubation, a commonly used practice is removing the anterior half of a semirigid collar and having an assistant provide manual in-line stabilization during intubation. This maneuver is achieved with the assistant standing at the head or side of the bed and using the fingers and palms of both hands to stabilize the patient's occiput and mastoid processes to gently counteract the forces of airway intervention [Figure 4]. While it is a suitable way to avoid the problem of severely decreased mouth opening, manual inline stabilization is far from perfect. Nolan found that, when compared with sniffing position, manual inline stabilization decreased laryngoscopic view in 45% of patients, that 22% of patients had a grade III (epiglottis only) view with inline stabilization, and that using a gum-elastic bougie greatly increased the rate of successful intubation within 45 seconds.[20] While manual inline stabilization anchors the occiput and the torso anchors the lower cervical spine, it is likely that laryngoscopic forces can still be translated to the mid-cervical spine. It is important to note that the anterior collar should be replaced after the airway is secured and the collar should be worn during other movements such as from a stretcher to an operating room (OR) table.

Practice patterns of airway management for cervical spine injury

Like many areas of medicine, practice patterns for airway management in patients with possible cervical spine injury have changed dramatically over the past several decades. Surgical cricothyrotomy was once advocated by Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines in these patients to minimize cervical spine displacement, but it was not well studied or always done. In the late 1980s, Holley and Jordan reviewed 133 intubations and found nasal intubation was done (71%) more than direct laryngoscopy with manual inline stabilization (22%).[21] In the late 1990s both Rosenblatt and McCrory found that anesthesiologists preferred awake fiberoptic (60-78%) over direct laryngoscopy under general anesthesia (32-40%).[22] Video laryngoscopes such as the Glidescope, not introduced until about the year 2000, are widely used in combination with manual inline stabilization or a complete hard cervical collar at our institution in order to minimize cervical spine displacement in these patients.

Airway management options

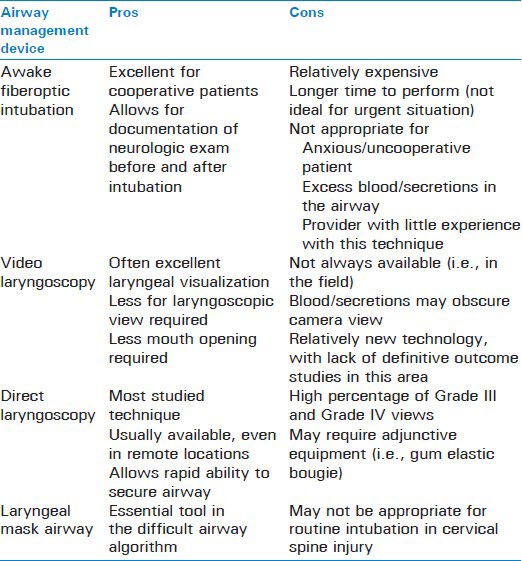

In order to choose among the available airway management options for patients with actual or potential cervical spine injury, providers must be familiar with the risks and benefits of each. Table 1 provides the pros and cons of commonly used airway management devices.

Table 1.

Airway management options for the patient with potential cervical spine injury

Awake fiberoptic intubation

Awake fiberoptic intubation is excellent for elective and semi urgent situations with cooperative patients. It allows for documentation of neurologic exam before and after intubation and surgical positioning. However, use of awake fiberoptic technique requires significant expertise and may be complicated in urgent or emergent situations, if a patient is too anxious to be cooperative, if a provider is not skilled in fiberoptic bronchoscopy, or if there is blood or other secretions in the airway.

With established provider skill in fiberoptic bronchoscopy, optimal patient selection, and adequate anesthesia of the airway, awake fiberoptic intubation has been shown to be feasible in many small studies. In a recent paper, Malcharek et al. showed that in a sample of patients at risk of secondary cervical injury, fiberoptic intubation and patient self-positioning in the prone position after intubation was feasible and successful.[23] For the anxious patient, studies have demonstrated that infusion of remifentanil or dexmedotomindine may allow for a more cooperative patient during the performance of an awake fiberoptic intubation in patients with cervical trauma.[24,25]

Video laryngoscopy

Video laryngoscopy, as mentioned earlier, is an excellent choice because its angulation and indirect nature requires less force for laryngoscopic view and endotracheal tube placement, and its relatively narrow blade requires less mouth opening than most traditional laryngoscopes. Acute angulation and less mouth opening explain how the Glidescope, when compared with direct laryngoscopy, was used to improve laryngoscopic view and successfully intubation patients wearing cervical collars in a study by Bathory et al.[26] Unfortunately, like fiberoptic intubation, video laryngoscopy may also be more difficult to access in urgent or emergent situations and may not work well if a provider is not comfortable with its use or there is blood in the airway that could obscure the camera view. Even with these limitations, some studies suggest better first-attempt success rates with video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy.[27]

While the use of manual in-line stabilization has been emphasized in limiting cervical spine motion during intubation, this technique has been shown to make direct laryngoscopy more challenging. Thus, the use of video laryngoscopy may allow an improved laryngeal view in the setting of manual in-line stabilization; although, it should be emphasized, that cervical spine motion may not be affected any less with video laryngoscopy as compared with direct laryngoscopy.[28] Because of the relatively new technology of video laryngoscopy, large trials are still needed to best elucidate where these devices should fit in the management of the patient with potential cervical injury.

Direct laryngoscopy

Direct laryngoscopy is technologically more simple than fiberoptic or video laryngoscopy and, therefore, excellent in emergent situations. As evidenced by a review of over 32,000 emergent intubations by anesthesiologists, in experienced hands, traditional direct laryngoscopy is safe and remarkably effective.[29] When Ong et al. compared video laryngoscopy and fiberoptic laryngoscopy with direct laryngoscopy using a Macintosh blade, they found direct laryngoscopy was faster in normal airways and at least equivalent in difficult airways.[30] Larger studies on actual patients and that control for operator experience level would be needed to further address this finding. Studies by Hastings and Gerling did not find a significant difference based on type of metal laryngoscope blade.[31,32] In immobilized patients, especially for emergent intubations, direct laryngoscopy with the use of a gum elastic bougie is an excellent choice to quickly and reliably secure the airway while minimizing the force to the cervical spine.

Laryngeal mask airway

Laryngeal mask airways (LMAs) remain controversial for airway management of patients with known or suspected cervical spine injury, as some studies have shown increased cervical spine displacement relative to intubation and other studies have shown no significant difference.[33,34]

In addition to providing ventilation in a potentially disastrous cannot intubate and cannot ventilate scenario, LMAs can often be used to facilitate tracheal intubation. A study by Arslan et al.,[35] compared different LMAs placed in patients wearing cervical collars.[36] Their findings suggest that the Airtraq single-use LMA may be associated with a shorter intubation time and less mucosal damage in patients with an immobilized cervical spine. The Fastrach LMA system has also been validated for use in difficult airway scenarios including cervical spine immobilization.[37] Joffe et al. demonstrated how a gum elastic bougie can be used to facilitate placement of an LMA-Proseal without an assistant.[35] This may be a valuable strategy in potential cervical spine injury patients without oropharyngeal or esophageal trauma.

Regardless of the device used, LMAs remain an essential tool in the difficult airway algorithm for all patients, including those with trauma and cervical spine injury.

Combination techniques

There have been no studies published so far to indicate potential benefit of combination techniques to minimize cervical spine movement during airway management. Indirect video laryngoscopy with fiberoptic bronchoscope used as flexible stylette appears to cause minimal movement and soft tissue pressure in the neck.

Additional concerns in cervical spine injury

Finally, there are several other important concerns for providers to keep in mind when caring for patients with cervical spine injury. Concurrent injuries to the head or other vital organs may need simultaneous attention during and after securement of the airway. Collars and the need to keep the neck in a straight position will make jugular central venous access more challenging. Succinylcholine should be used with caution in patients with potential spinal cord injury unless it has been less than 24-48 hours. It should not be used after 48 hours in patients with known spinal cord injury because of the risk of extra-junctional receptors and hyperkalemic cardiac arrest.[38]

CONCLUSION

Overall, there is no one perfect way to manage the airway in patients with potential cervical spine injury. Providers must use their judgment and weigh various risks like spinal cord injury, aspiration, and hypoxia in each patient and have the most experienced provider available to safely secure the airway. An airway management and anesthetic plan must be designed based on the patient, surgeon, situation urgency, and individual provider's level of expertise. Providers have to communicate with neurosurgeons about the plan and elicit information whenever possible about the injury and types of movement that are at highest risk of secondary injury. Providers also have to communicate with nurses and other practitioners about spine precautions and treat all trauma patients as spine-injured until proven otherwise. As always, providers have to document their reasoning in the anesthesia record to protect themselves and their patients from negative consequences.

While providers remain vigilant about preventing secondary injury in patients with cervical spine injury, they must keep in mind that forces during intubation and positioning are likely to pale in comparison to the forces that caused the initial injury. Thankfully, with a handful of exceptions, careful airway management is not associated with causing significant neurologic deficit, so efforts to safely care for patients with the most familiar technique are worth the effort.[39,40,41,42,43,44,45]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crosby ET, Lui A. The adult cervical spine: Implications for airway management. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37:77–93. doi: 10.1007/BF03007488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demetriades D, Charalambides K, Chahwan S, Hanpeter D, Alo K, Velmahos G, et al. Nonskeletal cervical spine injuries: Epidemiology and diagnostic pitfalls. J Trauma. 2000;48:724–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200004000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hackl W, Hausberger K, Sailer R, Ulmer H, Gassner R. Prevalence of cervical spine injuries in patients with facial trauma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:370–6. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.116894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchaud-Chabot A, Liote F. Cervical spine involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. A review. Joint Bone Spine. 2002;69:141–54. doi: 10.1016/s1297-319x(02)00361-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White AA, 3rd, Johnson RM, Panjabi MM, Southwick WO. Biomechanical analysis of clinical stability in the cervical spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;109:85–96. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197506000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crosby ET. Airway management in adults after cervical spine trauma. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1293–318. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ching RP, Watson NA, Carter JW, Tencer AF. The effect of post-injury spinal position on canal occlusion in a cervical spine burst fracture model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:1710–5. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199708010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etz CD, Kari FA, Mueller CS, Silovitz D, Brenner RM, Lin HM, et al. The collateral network concept: A reassessment of the anatomy of spinal cord perfusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1020–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson GD, Gorden CD, Oliff HS, Pillai JJ, LaManna JC. Sustained spinal cord compression: Part I: Time-dependent effect on long-term pathophysiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadley MN, Walters BC, Grabb PA, Oyesiku NM, Przybylski GJ, Resnick DK, et al. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries. Clin Neurosurg. 2002;49:407–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauswald M, Sklar DP, Tandberg D, Garcia JF. Cervical spine movement during airway management: Cinefluoroscopic appraisal in human cadavers. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:535–8. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(91)90106-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawin PD, Todd MM, Traynelis VC, Farrell SB, Nader A, Sato Y, et al. Cervical spine motion with direct laryngoscopy and orotracheal intubation. An in vivo cinefluoroscopic study of subjects without cervical abnormality. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:26–36. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwan I, Bunn F, Roberts I. Spinal immobilisation for trauma patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001:CD002803. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heath KJ. The effect of laryngoscopy of different cervical spine immobilisation techniques. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:843–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb04254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podolsky S, Baraff LJ, Simon RR, Hoffman JR, Larmon B, Ablon W. Efficacy of cervical spine immobilization methods. J Trauma. 1983;23:461–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bednar DA. Efficacy of orthotic immobilization of the unstable subaxial cervical spine of the elderly patient: Investigation in a cadaver model. Can J Surg. 2004;47:251–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goutcher CM, Lochhead V. Reduction in mouth opening with semi-rigid cervical collars. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:344–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasarn ML, Conrad B, Del Rossi G, Horodyski M, Rechtine GR. Motion generated in the unstable cervical spine during the application and removal of cervical immobilization collars. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1609–13. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182471d9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horodyski M, DiPaola CP, Conrad BP, Rechtine GR., 2nd Cervical collars are insufficient for immobilizing an unstable cervical spine injury. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:513–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nolan JP, Wilson ME. Orotracheal intubation in patients with potential cervical spine injuries. An indication for the gum elastic bougie. Anaesthesia. 1993;48:630–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb07133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holley J, Jorden R. Airway management in patients with unstable cervical spine fractures. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:1237–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenblatt WH, Wagner PJ, Ovassapian A, Kain ZN. Practice patterns in managing the difficult airway by anesthesiologists in the United States. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:153–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199807000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malcharek MJ, Rogos B, Watzlawek S, Sorge O, Sablotzki A, Gille J, et al. Awake fiberoptic intubation and self-positioning in patients at risk of secondary cervical injury: A pilot study. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2012;24:217–21. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31824da7e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeganeh N, Roshani B, Azizi B, Almasi A. Target-controlled infusion of remifentanil to provide analgesia for awake nasotracheal fiberoptic intubations in cervical trauma patients. J Trauma. 2010;69:1185–90. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181cb4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avitsian R, Lin J, Lotto M, Ebrahim Z. Dexmedetomidine and awake fiberoptic intubation for possible cervical spine myelopathy: A clinical series. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2005;17:97–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ana.0000161268.01279.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bathory I, Frascarolo P, Kern C, Schoettker P. Evaluation of the GlideScope for tracheal intubation in patients with cervical spine immobilisation by a semi-rigid collar. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1337–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosier JM, Stolz U, Chiu S, Sakles JC. Difficult airway management in the emergency department: GlideScope videolaryngoscopy compared to direct laryngoscopy. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:629–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aziz M. Airway management in neuroanesthesiology. Anesthesiol Clin. 2012;30:229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephens CT, Kahntroff S, Dutton RP. The success of emergency endotracheal intubation in trauma patients: A 10-year experience at a major adult trauma referral center. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:866–72. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181ad87b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ong JR, Chong CF, Chen CC, Wang TL, Lin CM, Chang SC. Comparing the performance of traditional direct laryngoscope with three indirect laryngoscopes: A prospective manikin study in normal and difficult airway scenarios. Emerg Med Australas. 2011;23:606–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hastings RH, Vigil AC, Hanna R, Yang BY, Sartoris DJ. Cervical spine movement during laryngoscopy with the Bullard, Macintosh, and Miller laryngoscopes. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:859–69. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199504000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerling MC, Davis DP, Hamilton RS, Morris GF, Vilke GM, Garfin SR, et al. Effects of cervical spine immobilization technique and laryngoscope blade selection on an unstable cervical spine in a cadaver model of intubation. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:293–300. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.109442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller C, Brimacombe J, Keller K. Pressures exerted against the cervical vertebrae by the standard and intubating laryngeal mask airways: A randomized, controlled, cross-over study in fresh cadavers. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kihara S, Watanabe S, Brimacombe J, Taguchi N, Yaguchi Y, Yamasaki Y. Segmental cervical spine movement with the intubating laryngeal mask during manual in-line stabilization in patients with cervical pathology undergoing cervical spine surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:195–200. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200007000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joffe AM, Schroeder KM, Shepler JA, Galgon RE. Validation of the unassisted, gum-elastic bougie-guided, laryngeal mask airway-ProSeal placement technique in anaesthetized patients. Indian J Anaesth. 2012;56:255–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.98771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arslan ZI, Yildiz T, Baykara ZN, Solak M, Toker K. Tracheal intubation in patients with rigid collar immobilisation of the cervical spine: A comparison of Airtraq and LMA CTrach devices. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1332–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerstein NS, Braude DA, Hung O, Sanders JC, Murphy MF. The Fastrach Intubating Laryngeal Mask Airway: An overview and update. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57:588–601. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martyn JA, Richtsfeld M. Succinylcholine-induced hyperkalemia in acquired pathologic states: Etiologic factors and molecular mechanisms. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:158–69. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scannell G, Waxman K, Tominaga G, Barker S, Annas C. Orotracheal intubation in trauma patients with cervical fractures. Arch Surg. 1993;128:903–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200077014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shatney CH, Brunner RD, Nguyen TQ. The safety of orotracheal intubation in patients with unstable cervical spine fracture or high spinal cord injury. Am J Surg. 1995;170:676–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talucci RC, Shaikh KA, Schwab CW. Rapid sequence induction with oral endotracheal intubation in the multiply injured patient. Am Surg. 1988;54:185–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suderman VS, Crosby ET, Lui A. Elective oral tracheal intubation in cervical spine-injured adults. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38:785–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03008461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCrory C, Blunnie WP, Moriarty DC. Elective tracheal intubation in cervical spine injuries. Ir Med J. 1997;90:234–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright SW, Robinson GG, 2nd, Wright MB. Cervical spine injuries in blunt trauma patients requiring emergent endotracheal intubation. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:104–9. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(92)90039-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norwood S, Myers MB, Butler TJ. The safety of emergency neuromuscular blockade and orotracheal intubation in the acutely injured trauma patient. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:646–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]