Abstract

Objectives

Since the introduction of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in 2006, there have been considerable efforts at the national and state levels to monitor uptake and better understand the individual and system-level factors that predict who gets vaccinated. A common method of measuring the vaccination status of adolescents is through parental recall. We examined how the accuracy of parents' reports of their daughters' HPV vaccination status varied by social characteristics.

Methods

Data were taken from the 2009–2010 National Immunization Survey (NIS)-Teen, which includes a household interview and a provider-completed immunization history. We evaluated concordance between parents' and providers' reports of teens' HPV vaccine initiation (≥1 dose) and completion (≥3 doses). We assessed bivariate associations of sociodemographic characteristics with having a concordant, false-positive (overreporting) or false-negative (underreporting) report, and used multinomial logistic regression to estimate the independent impact of each characteristic.

Results

In bivariate analyses, concordance of parent-reported HPV vaccine initiation was associated with each of the sociodemographic characteristics investigated. In regression models, self-reported nonwhite race, lower household income, and lower education level of the teen's mother were associated with a higher likelihood of having a false-negative parental report than a concordant report.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that, while estimates of overall coverage based on parental report may be unbiased, the differences in the accuracy of parental report could result in misleading estimates of disparities in HPV vaccine coverage.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination has been promoted as an effective public health intervention to prevent cervical cancer.1 Recommended for girls aged 11 and 12 years and previously unvaccinated women up to age 26 years,2 it is administered in three doses during a period of six months. Recently, the recommendations have been updated to also include boys aged 11 and 12 years.3

The effectiveness of HPV vaccination for reducing cervical cancer depends upon uptake. Not surprisingly, there have been considerable efforts to monitor uptake and better understand the individual and system-level factors that predict who gets vaccinated.4–7 The validity of the results from these studies, however, rests with the measurement of vaccination status.

A common method of measuring vaccination status is through parental recall. For example, the National Health Interview Survey asks parents about their awareness of the vaccine for HPV, whether their child had received the shot, and, if so, how many doses the child had received.8 Other national and regional surveys similarly rely on parental/guardian reports.5,7,9,10

HPV vaccination uptake has been lower than was initially hoped.5,8,11 Additionally, substantial attention has been paid to social group differences in initiation and completion of the three-dose series. Results have been mixed, with some researchers concluding that uptake and vaccination completion rates are lower among girls from disadvantaged social groups7,12,13 and others reporting equal or higher rates for girls from lower socioeconomic backgrounds or from minority cultural groups.7,8

Systematic measurement error resulting from using parental reports of vaccine status may affect the validity of estimates. Two types of error may be particularly important. First is the issue of memory or recall bias.14,15 Respondents may forget whether their child had the HPV vaccine or the number of doses received. However, given the media attention to the HPV vaccine16 and the three-dose vaccination schedule, this issue may be less of a problem than for other vaccines.

A second source of measurement error is social desirability bias, or the tendency of survey respondents to give answers that they think are more socially acceptable. In general, in studies of health behaviors, people will say they engaged in socially sanctioned health behaviors (e.g., preventive care) when they did not.17 The case of HPV vaccine is somewhat different from many preventive health behaviors because there may be competing social norms. Most parents in studies of social attitudes understand the link between HPV vaccination and cervical cancer.18 Thus, the socially desirable answer is to indicate that their child has been vaccinated. However, some parents express concern that HPV vaccination is associated with sexual activity,18 which could theoretically lead parents to underreport vaccination status if they are concerned that interviewers will think that their child is sexually active.

Reporting error at the population level is of concern because it could bias estimates of uptake and completion of the vaccination series. It is also important to look at systematic differences between social groups (e.g., race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status [SES]) in measuring the accuracy of vaccination status. If such systematic differences exist, estimates of whether there are disparities in HPV vaccine uptake will be distorted.

Dorell and colleagues examined whether parents over- or underreport vaccination status.19 Using data from the 2008 National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen), which has the advantage of collecting both provider and parental reports of vaccine status, they found that, while agreement between household and provider report for the HPV vaccine was highest overall of any of the adolescent vaccines (Kappa=0.76 for initiation among parents reporting from recall only), disagreement tended to be in the direction of underreporting. Similarly, in a study comparing the reports of mothers and girls with medical records, Stupiansky et al. found that mothers underreported the vaccination status of their daughters.20

Recently, Ojha et al. compared the accuracy of adult proxy recall for teens' HPV vaccine status with the use of household immunization records using the 2010 NIS-Teen.21 The findings indicated that sensitivity of adult proxy recall tended to be lower than specificity, and that adult proxy respondents who were the mothers (vs. the fathers), non-Hispanic white, older, and more educated tended to provide more accurate reports. Overall, they conclude that adult recall of vaccine initiation and use of shot cards “have reasonable accuracy for classifying HPV vaccination status.”21 However, the researchers did not examine (1) whether sociodemographic factors are associated with over- or underreporting and (2) the implications of reporting error for estimates of vaccination status for specific subgroups.

Using data from the NIS-Teen, the data used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to generate national estimates, we build on the existing literature focusing on the accuracy of parental reports of HPV vaccine status by sociodemographic characteristics that are markers of advantage and disadvantage. We examined (1) concordance between parental and provider reports for initiation of HPV vaccine and completion of the recommended three doses and (2) whether both under- and overreporting by parents are associated with social characteristics.

METHODS

Data

We used data from the 2009 and 2010 NIS-Teen public-use files. The NIS-Teen is a nationally representative, random-digit-dial survey of households with 13- to 17-year-old children. The survey uses a stratified sampling design.22 In addition to a household interview, the adult responding to the survey is asked for consent to contact the teen's medical providers. If consent is given, all of the identified medical providers are mailed an immunization history questionnaire. Teens are flagged as having adequate provider data if the providers identified by the household survey respondent supplied enough information to determine the teen's vaccination status. Our sample was limited to females only, as the HPV vaccine was not recommended for boys until 2011. We identified 18,290 female teens with complete information about the HPV vaccine from the household and provider surveys.

Measures

In more than 94% of cases in 2009 and 2010, the household interview was completed by the teen's parent; we refer to this information as “parent-reported.” The parent was asked whether an immunization card for the teen was available and whether it was complete. If a complete immunization card was available, the respondent answered questions based on that document, with follow-up questions about whether the teen had received additional doses of the vaccine that were not on the card. We categorized these people as “immunization card plus recall respondents.” The sample was divided into two groups: immunization card plus recall (n=4,308) and recall only (n=13,982).

Girls were coded as having initiated the vaccine series if they had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine. Those who had received ≥3 doses were coded as having completed the series. Thus, there were four vaccination status variables: parent-reported initiation, parent-reported completion, provider-reported initiation, and provider-reported completion.

Covariates include characteristics of the adolescent, such as age, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, and other/multiracial), and insurance type (private, public/Medicaid, other coverage, no reported coverage, or missing). In the survey, respondents could indicate multiple forms of insurance coverage; for this analysis, we hierarchically coded the insurance variable such that if the teen had any private coverage, she was coded as privately insured. If the teen had no private coverage but any public coverage, she was coded as publicly insured. If the teen had no private or public coverage but reported other coverage, she was coded as having other coverage. If the teen reported no insurance in any of the previous categories, she was coded as having no reported coverage. A large proportion of teens in our sample (14.9%) were missing information about insurance coverage, which we preserved as a separate category.

Characteristics of the teen's mother included education level (<12 years, 12 years, ≥12 years but non-college graduate, and college graduate or higher) and marital status (currently married or not). Household characteristics included four-category census region, whether the family's home was owned or occupied by another arrangement (e.g., renting), and household income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL) (<100%, 100%–199%, 200%–299%, and ≥300% FPL). We imputed the measure of FPL percentage using hot deck imputation23 due to a large proportion of missing data.

Statistical analysis

Provider reports of vaccination status were considered the gold standard. We compared the accuracy of parents' reports (based on recall only or the combination of recall and an immunization card) with provider reports. We calculated the false-positive rate (false positives/[false positives + true negatives]), or (1-Specificity), and false-negative rate (false negatives/[false negatives + true positives]), or (1-Sensitivity). We also examined characteristics associated with the probability of being a false-positive (overreporting) or false-negative (underreporting) case. For these analyses, the denominator was the total number of cases. Finally, we assessed the simultaneous relationship of the sociodemographic characteristics to having a false-positive or false-negative report using multinomial logistic regression (with concordant report as the base outcome). We did not apply survey weights in any of the analyses presented because we were interested in patterns of misclassification within the sample; as a sensitivity analysis, however, the multivariate analyses were recomputed using the weights. We note any results substantially changed by weighting, and the weighted results are available upon request. For all analyses, we adjusted the standard errors to account for the complex sampling design (i.e., primary sampling units and strata).

RESULTS

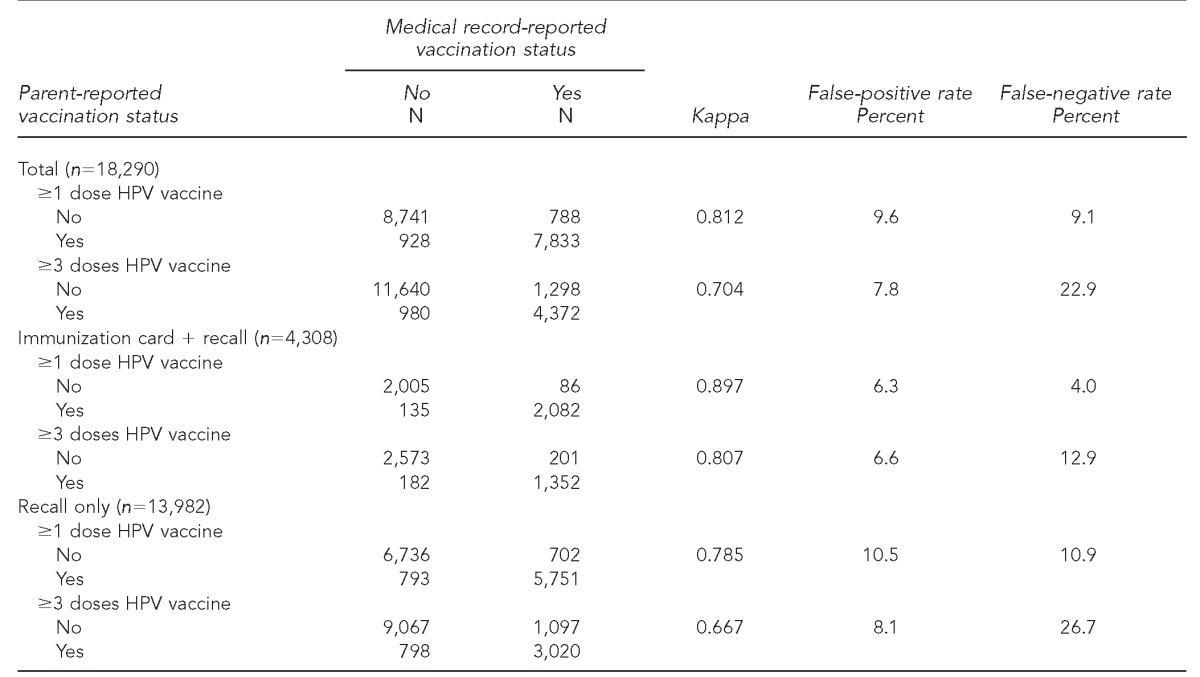

Table 1 reports the level of agreement between household and provider report by group (total, immunization card + recall, and recall only). Agreement was fairly high overall for HPV vaccine initiation (Kappa=0.812). It was higher in the immunization card + recall group (Kappa=0.897) than among recall-only respondents (Kappa=0.785). Agreement was lower for HPV vaccine series completion (Kappa=0.807 in the immunization card + recall group; Kappa=0.667 in the recall-only group) than for reports of vaccine initiation. False-positive and false-negative rates were comparable for each group for HPV vaccine initiation, but false-negative rates were higher than false-positive rates for vaccine series completion (22.9% vs. 7.8% in the total group) (Table 1). Sensitivity and specificity were both about 90% for vaccine initiation in the total group, but sensitivity was much lower (77%) for vaccine series completion (data not shown).

Table 1.

Accuracy of parent-reported HPV vaccine status among female teens with complete household surveys and adequate provider data: NIS-Teen, 2009–2010

HPV = human papillomavirus

NIS = National Immunization Survey

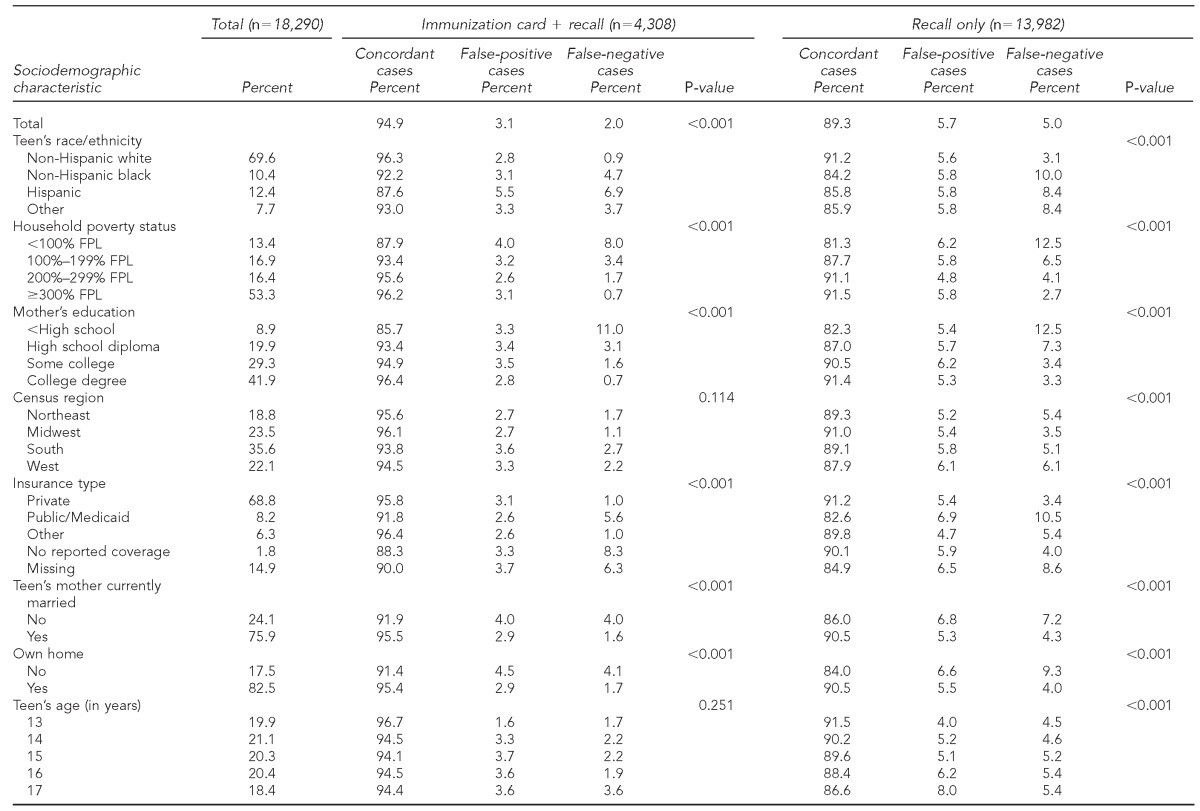

Table 2 reports sample characteristics and the accuracy of parental reports of vaccination status by sociodemographic characteristics. Among those responding using recall only (i.e., no immunization card), concordance of reporting the HPV vaccine initiation varied significantly by every sociodemographic characteristic investigated (p<0.001). Higher percentages of concordant reports and lower percentages of false-negative reports were consistently found among those with socially advantaged characteristics. For example, among teens in households with incomes ≥300% of the FPL, 91.5% had a parental report of HPV vaccine initiation that was concordant with the provider report, and 2.7% had a false-negative parental report. Among teens in households with income <100% of the FPL, however, 81.3% had a concordant report and 12.5% had a false-negative household report. We found the same pattern of results for concordance between parental reports that were aided by referring to the child's immunization card and provider reports. Concordance was consistently higher and false-negative reports were consistently lower among the more socially advantaged.

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with concordance of parent-reported HPV vaccine initiation status with provider record: NIS-Teen, 2009–2010

Note: P-values are from adjusted Wald tests.

HPV = human papillomavirus

NIS = National Immunization Survey

FPL = federal poverty level

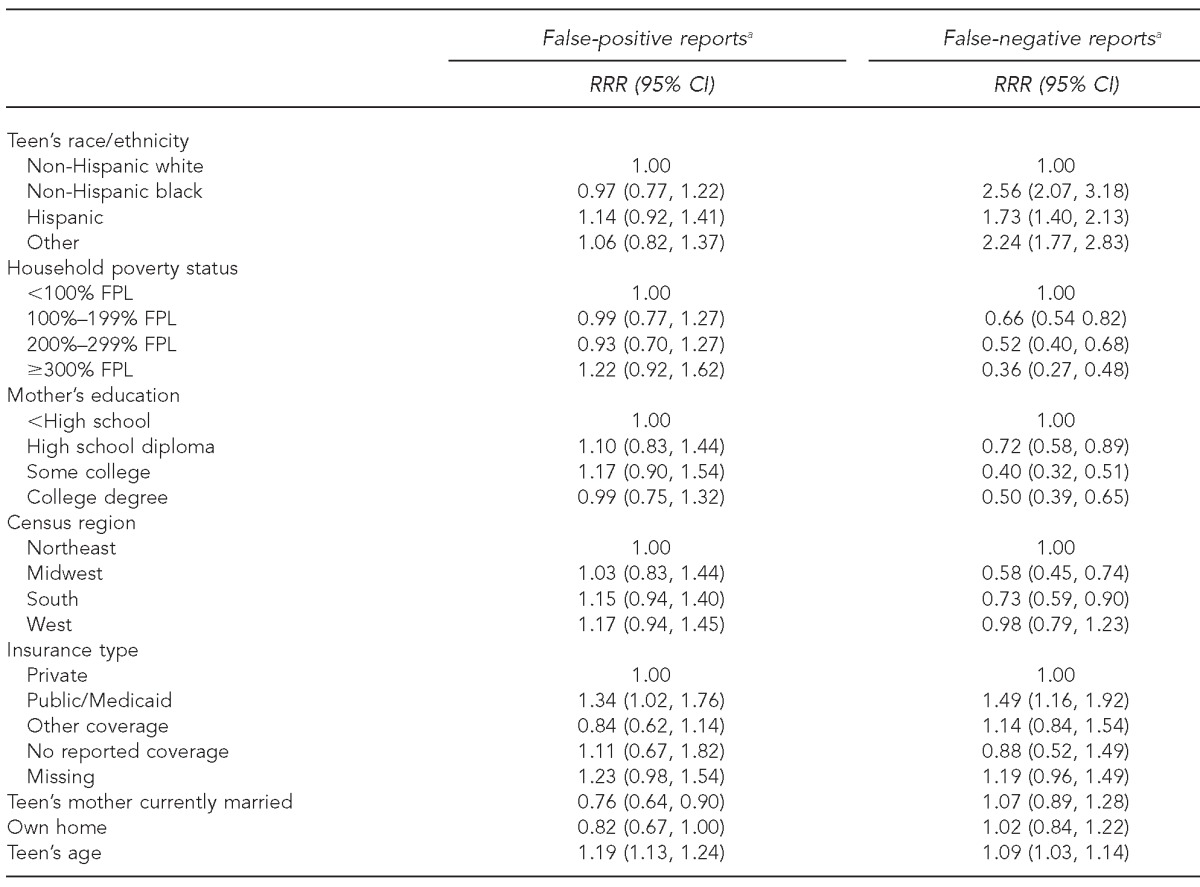

Results from the multinomial logistic regression model (Table 3) show that few characteristics were associated with the likelihood of a false-positive parental report compared with a concordant parental report. Notably, however, teens who were publicly insured were more likely to have a false-positive report (relative risk ratio [RRR] = 1.34, p=0.037) than privately insured teens. Nonwhite teens had a higher probability of false-negative parental report than non-Hispanic white teens (RRR range: 1.73–2.56). Higher household income and higher level of mother's education were associated with a lower likelihood of a false-negative household report. Teens with public insurance were more likely than teens with private insurance to have a false-negative report (RRR=1.49, p=0.002). When the models were recomputed using survey weights, results were broadly similar. While the direction of all relationships remained the same, there were some changes in statistical significance. Self-reported Hispanic race/ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity) became significantly associated with a higher probability of having a false-positive report of HPV vaccine initiation, and the coefficient for public insurance became marginally nonsignificant (p=0.075). For the weighted analysis, looking at correlates of false-negative reports, having no reported health insurance coverage was associated with a decreased likelihood of a false-negative report, while missing insurance coverage was associated with a greater likelihood of a false-negative report.

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression results for agreement between household and provider report of HPV vaccine initiation, with base outcome concordant (n=18,290): NIS-Teen, 2009–2010

aReference group is concordant.

HPV = human papillomavirus

NIS = National Immunization Survey

RRR = relative risk ratio

CI = confidence interval

FPL = federal poverty level

DISCUSSION

Consistent with previous research,19,21 we found that parents are fairly accurate in reporting their daughters' HPV vaccination status. However, Dorell and colleagues found that when parents' reports were inaccurate, the HPV vaccine tended to be underreported, while we found that false-positive and false-negative rates were similar for HPV vaccine initiation. Overall, the two types of errors tended to cancel each other out, resulting in estimates based on parents' recall coming close to the true value in the population. Completion of the series, however, did tend to be underreported.

Not surprisingly, parents who had access to their child's immunization card to aid their recall were more accurate in reporting both initiation and completion of the HPV vaccine series. While reporting using immunization cards only appears to result in a tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity,21 in our study, reporting based on the immunization card combined with recall resulted in fairly high sensitivity and specificity for initiation (more than 93% for both). However, many surveys are not designed to have parents access the card, and even in this survey, only 24% of the parents were able to do so. Relying on access to immunization cards, therefore, seems an unrealistic strategy to increase the accuracy of parents' reports in most surveys.

Ojha and colleagues found that the sensitivity and specificity of household reports vary by sociodemographic characteristics. Our contribution is to demonstrate that the net effect of this misclassification resulted in underreporting for disadvantaged groups, and that this assertion held true in multivariate analyses. That is, sociodemographic characteristics that are indicators of disadvantage were associated with a higher likelihood of parents reporting that their daughter had not received the HPV vaccine when, in fact, she had. Girls who were reported to be of nonwhite race/ethnicity, lower household income, lower levels of mother's education, and on public insurance were more likely to have a false-negative parental report of vaccination status. This finding may partially explain conflicting findings regarding disparities in HPV vaccine initiation. For example, Dorell and colleagues,11 using provider-reported NIS-Teen data, found no differences in initiation of the vaccine series by race/ethnicity, mother's education level, or household income. In contrast, a recently published study using parent-reported data from the same survey found disparities in HPV vaccine initiation based on the same characteristics.12 Our findings suggest that differences in underreporting of the vaccine by social group could exaggerate disparities in data using the parent's report of the child's vaccination status.

There are several possible underlying causes for underreporting in certain groups. The HPV vaccine is still fairly new, and it is possible that some parents had not heard of it; therefore, they might not remember that their daughters had received it. Indeed, previous research has found that higher SES is associated with greater awareness of the HPV vaccine.24–26 In addition, SES is related to health-care services use among adolescents, such as having a usual source of care or a recent preventive care visit,27,28 which could make it more difficult for parents to remember what, when, and where services were received.

Underreporting may also be due to social desirability. Considerable media attention and political controversy have linked the vaccine to sexual activity.16,29,30 While studies have varied in their estimates, at least a small minority of parents report concern about sexual activity in relation to the HPV vaccine. One national study found that 22% of parents believed that vaccinating their child would tacitly condone sex.24 While no studies that we are aware of have explored the effect of such concerns on reporting, it is possible that parents might not report that their daughter had the vaccine because of the association with sexual activity, and this bias could be stronger among particular social groups.

Limitations

Our study had several important limitations. These data predated the recommendation of the HPV vaccine for boys, and the accuracy of parental reporting may be different for boys than for girls. In addition, we relied on data from households that participated and had a complete provider report, as we used provider-reported vaccine status as the gold standard against which to compare parental report. As such, these data may overrepresent more affluent households.22 In the 2009–2010 NIS-Teen, 42% of female teens lacked adequate provider data. Weighting adjusts for nonresponse; thus, we have some confidence in our results in that they were similar after weighting. However, if nonrespondents are systematically different in vaccine behavior compared with their demographically similar counterparts who did respond, even weighting will not yield accurate estimates of coverage. Our analysis also used the provider report as the gold standard, although previous research shows that there is error in such data resulting from factors, including receiving vaccinations from more than one provider, moving, poor handwriting, or transcription mistakes.31 Finally, bias could be introduced due to the fact that the 2009 and 2010 NIS-Teen did not include a cell-phone sample, and there may be important differences between families who had landlines and those who did not.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings have important implications for estimates of HPV vaccine uptake based on surveys that rely solely on parent-reported vaccination status. Overall coverage estimates for HPV vaccine initiation based on parental report are likely unbiased, but coverage estimates for vaccine series completion would underestimate the actual coverage in the teen population. Additionally, differences in the accuracy of parental report by social characteristics could result in misleading estimates of disparities in HPV vaccine coverage.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonanni P, Boccalini S, Bechini A. Efficacy, duration of immunity and cross protection after HPV vaccination: a review of the evidence. Vaccine. 2009;27(Suppl 1):S46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson H, Chesson H, Unger ER. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(50):1705–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Jin Y, Huang B, Namakydoust A, Zimet GD. Rates of human papillomavirus vaccination, attitudes about vaccination, and human papillomavirus prevalence in young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1103–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817051fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor LD, Hariri S, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2008. Prev Med. 2011;52:398–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz LE, Hariri S, Unger ER, Saraiya M, Datta SD, Dunne EF. Post-licensure monitoring of HPV vaccine in the United States. Vaccine. 2010;28:4731–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pruitt SL, Schootman M. Geographic disparity, area poverty, and human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:525–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laz TH, Rahman M, Berenson AB. An update on human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among 11–17 year old girls in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vaccine. 2012;30:3534–40. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerry SL, De Rosa CJ, Markowitz LE, Walker S, Liddon N, Kerndt PR, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in high-risk communities. Vaccine. 2011;29:2235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiro JA, Tsui J, Bauer HM, Yamada E, Kobrin S, Breen N. Human papillomavirus vaccine use among adolescent girls and young adult women: an analysis of the 2007 California Health Interview Survey. J Womens Health. 2012;21:656–65. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorell CG, Yankey D, Santibanez TA, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination series initiation and completion, 2008–2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128:830–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polonijo AN, Carpiano RM. Social inequalities in adolescent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: a test of fundamental cause theory. Soc Sci Med. 2013;82:115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong CA, Berkowitz Z, Dorell CG, Anhang Price R, Lee J, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among 9- to 17-year-old girls: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Cancer. 2011;117:5612–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradburn NM, Sudman S, Wansink B. Revised ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004. Asking questions: the definitive guide to questionnaire design—for market research, political polls, and social and health questionnaires. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudman S, Bradburn NM. Effects of time and memory factors on response in surveys. J Am Stat Assoc. 1973;68:805–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowler EF, Gollust SE, Dempsey AF, Lantz PM, Ubel PA. Issue emergence, evolution of controversy, and implications for competitive framing: the case of the HPV vaccine. Int J Press/Politics. 2011;17:169–89. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newell SA, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. The accuracy of self-reported health behaviors and risk factors relating to cancer and cardiovascular disease in the general population: a critical review. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:211–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trim K, Nagji N, Elit L, Roy K. Parental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards human papillomavirus vaccination for their children: a systematic review from 2001 to 2011. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:921236. doi: 10.1155/2012/921236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorell CG, Jain N, Yankey D. Validity of parent-reported vaccination status for adolescents aged 13–17 years: National Immunization Survey-Teen, 2008. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 2):60–9. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stupiansky NW, Zimet GD, Cummings T, Fortenberry JD, Shew M. Accuracy of self-reported human papillomavirus vaccine receipt among adolescent girls and their mothers. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:103–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojha RP, Tota JE, Offutt-Powell TN, Klosky JL, Ashokkumar R, Gurney JG. The accuracy of human papillomavirus vaccination status based on adult proxy recall or household immunization records for adolescent females in the United States: results from the National Immunization Survey-Teen. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:281–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain N, Singleton JA, Montgomery M, Skalland B. Determining accurate vaccination coverage rates for adolescents: the National Immunization Survey-Teen 2006. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:642–51. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andridge RR, Little RJA. A review of hot deck imputation for survey non-response. Int Stat Rev. 2010;78:40–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-5823.2010.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen JD, Othus MK, Shelton RC, Li Y, Norman N, Tom L, et al. Parental decision making about the HPV vaccine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2187–98. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes J, Cates JR, Liddon N, Smith JS, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Disparities in how parents are learning about the human papillomavirus vaccine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:363–72. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gollust SE, Attanasio L, Dempsey A, Benson AM, Fowler EF. Political and news media factors shaping public awareness of the HPV vaccine. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23:e143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newacheck PW, Hung YY, Park MJ, Brindis CD, Irwin CE., Jr Disparities in adolescent health and health care: does socioeconomic status matter? Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1235–52. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irwin CE, Jr, Adams SH, Park MJ, Newacheck PW. Preventive care for adolescents: few get visits and fewer get services. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e565–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Springen K. HPV vaccine: why so unpopular? Newsweek. 2008. Feb 24, [cited 2013 Sep 5]. Available from: URL: http://www.newsweek.com/hpv-vaccine-why-so-unpopular-93479.

- 30.Blumenthal R. Texas is first to require cancer shots for schoolgirls. New York Times. 2007. Feb 3, [cited 2013 Sep 5]. Available from: URL: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/03/us/03texas.html.

- 31.Khare M, Ezzati-Rice TM, Battaglia MP, Zell ER. An assessment of misclassification error in provider-reported vaccination histories. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Statistical Association; 2001 Aug 5–9; Alexandria, Virginia. [cited 2013 Sep 5]. Available from: URL: http://www.amstat.org/sections/SRMS/Proceedings. [Google Scholar]