Abstract

Objectives

Smoking, the leading cause of disease and death in the United States, has been linked to a number of health conditions including cancer and cardiovascular disease. While people with a disability have been shown to be more likely to report smoking, little is known about the prevalence of smoking by type of disability, particularly for adults younger than 50 years of age.

Methods

We used data from the 2009–2011 National Health Interview Survey to estimate the prevalence of smoking by type of disability and to examine the association of functional disability type and smoking among adults aged 18–49 years.

Results

Adults with a disability were more likely than adults without a disability to be current smokers (38.8% vs. 20.7%, p<0.001). Among adults with disabilities, the prevalence of smoking ranged from 32.4% (self-care difficulty) to 43.8% (cognitive limitation). When controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, having a disability was associated with statistically significantly higher odds of current smoking (adjusted odds ratio = 1.57, 95% confidence interval 1.40, 1.77).

Conclusions

The prevalence of current smoking for adults was higher for every functional disability type than for adults without a disability. By understanding the association between smoking and disability type among adults younger than 50 years of age, resources for cessation services can be better targeted during the ages when increased time for health improvement can occur.

Smoking is the leading cause of disease and death in the United States.1 It is estimated to cause 443,000 deaths per year in the U.S.,2 and average annual health-care-related expenditures are estimated at $96 billion during 2000–2004.2 Smoking has been linked to a number of adverse health conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and reproductive health issues.3,4

Disability affects more than 56 million Americans,5 with annual health-care expenditures associated with disability approaching $400 billion as of 2006.6 Among older adults, disability is often associated with the development or worsening of chronic conditions; as a consequence, disability is often equated with ill health. While this perception may be reinforced given that adults with a disability have been shown to have a lower self-rated health status than adults without disabilities,7 a Surgeon General's report provided ample evidence arguing that this disparity in health is largely preventable. People with disabilities can and should lead as healthy a life as people without disabilities.8

People with disabilities report a higher prevalence of smoking than do those without disabilities.9,10 Medicare enrollees with a disability who smoke have been shown to have lower mental and physical function than those who never smoked.11 People with rheumatoid arthritis, which is a leading disabling condition,12 are more likely to be current smokers than those without rheumatoid arthritis.13 In addition, cardiovascular disease and pulmonary disease, both of which are associated with smoking,3,4 are the third and fourth most commonly reported causes of disability, respectively.12

Despite condition-specific information and state-level surveillance reports, there is little nationally representative information on the prevalence of smoking by functional type of disability. Such information is critical for understanding how the prevalence of smoking may differ among people with disabilities. A better understanding of any differences that may exist can be used to explore how best to tailor cessation intervention efforts toward people with a disability. Using data from the 2009–2011 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS),14 we estimated smoking prevalence by disability type among adults aged 18–49 years.

METHODS

Data sources

We obtained data for this study from the 2009–2011 NHIS,14 a nationally representative, in-person household survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population. For this survey, which is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, interviewers collect comprehensive demographic, health, behavioral risk, preventive health, and disability data. NHIS data are used to monitor trends in illness and disability and track progress toward achieving national health objectives.

The NHIS consists of core questions and supplements, including household, family, and sample adult surveys. The household and family surveys collect demographic and health information on all household residents and family members, respectively. One adult from each family is randomly selected to provide information on specific conditions, health status, and health behaviors. The smoking-related questions are asked in the sample adult survey, and the disability questions are asked as either part of the family questionnaire or the sample adult survey, depending on year. A total of 74,352 respondents completed both sets of questions during the survey years included, and 40,886 of them were 18–49 years of age. A total of 133 respondents were excluded from all analyses due to missing smoking data, leaving a total of 40,753 respondents who were included in the analysis. Respondents who had missing responses from select demographic variables were excluded from those individual analyses but not from analyses of responses for other variables.

Smoking definition

Two questions were used to determine cigarette smoking status: “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” and “Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?” We defined current smokers as people who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and who currently smoke every day or some days. Former smokers were defined as people who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime but do not currently smoke. Never smokers were defined as people who reported not smoking 100 cigarettes during their lifetime.

Disability definition

According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health model, disability is an interaction of a person's health condition, environment, and other personal factors that can limit functioning.15 Further aligning with the concept of disability identified in the Americans with Disabilities Act, the American Community Survey (ACS) defines disability as functional limitations that affect a person's participation in activities. Six questions identifying functional types of disability from the ACS were asked on the 2009–2011 NHIS.16 A person is considered to have a disability if he or she, or a proxy respondent, answers affirmatively to having at least one of the following serious limitations: hearing, vision (even when wearing glasses), cognitive (concentrating, remembering, or making decisions), or ambulatory (walking or climbing stairs); or any limitation with the following: self-care (dressing or bathing) or independent living (e.g., running errands or visiting a doctor's office). The disability types are not mutually exclusive, and respondents could have more than one type of disability. The six categories of disability were used collectively and individually to define disability in assessing the association between current smoking and disability.

Statistical analyses

We used SAS®-callable SUDAAN® software17,18 to obtain estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of disability, type of disability, and current smoking prevalence. We obtained estimates for current smokers and never smokers stratified by gender, sociodemographic characteristics, and disability. The data were weighted to account for differential probability of selection and nonresponse, as well as to adjust for the age, sex, and race/ethnicity population totals. We adjusted the weights to account for the three years of data. Estimates were age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population.19 We used t-tests to assess the statistical significance of the differences between disability type and no disability. Because the disability types are not mutually exclusive, we considered non-overlapping CIs to indicate significant differences between individual disability types at p<0.05.

We used logistic regression models to assess the associations between current smoking and disability and current smoking and type of disability, respectively. Both unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were obtained. Independent covariates included in the adjusted models were demographic characteristics (i.e., sex, age, race/ethnicity, and marital status), socioeconomic characteristics (i.e., education, employment, and income), and having health insurance. The dependent variable for the logistic regression models was current smoking vs. nonsmoking (both former and never smokers combined).20 We also ran parallel models for a sensitivity analysis, with the outcome being current smokers vs. never smokers.

We limited our analysis to respondents aged 18–49 years for several reasons. First, smoking prevalence is highest among younger adults (aged 18–64 years) and lowest among adults aged 65 years and older.1 Second, the health effects of quitting smoking are greater the earlier a person stops smoking.21,22 Third, the absolute risk of death, and presumably disability, attributable to smoking increases with age.23 Additionally, although the prevalence of disability increases with age, 18- to 49-year-olds account for nearly 12 million of the 39 million adults with a disability represented in our data. Focusing on younger respondents can allow increased time for health improvement if cessation occurs, regardless of whether smoking led to the disabling condition or, on the other hand, stressors around having a disability contributed to a person's smoking or being hesitant to quit.

RESULTS

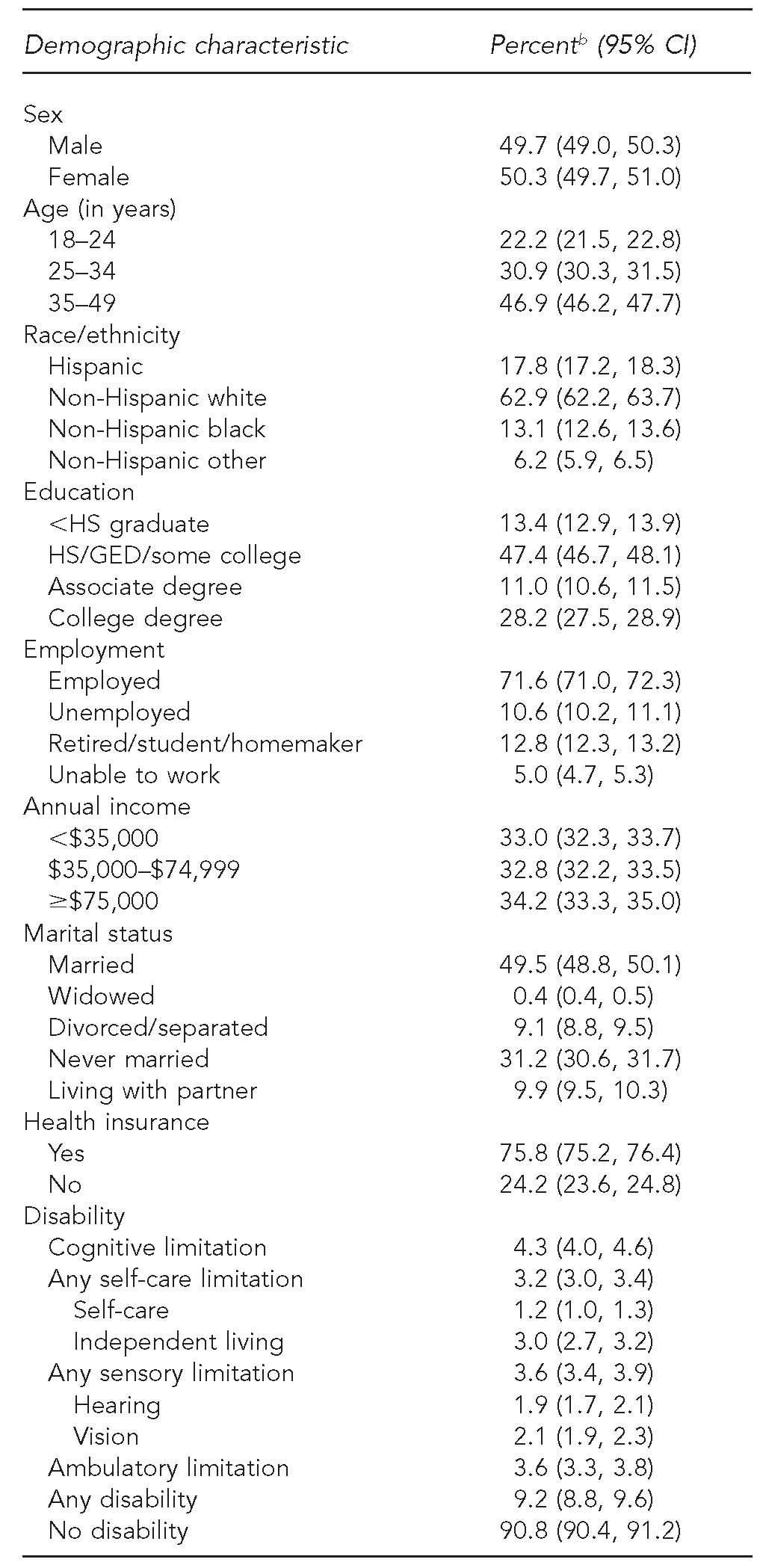

Overall demographic characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1. Approximately 9.2% of U.S. adults aged 18–49 years reported having a disability. By type, 4.3% of adults in that age group reported a cognitive limitation, 1.2% reported a self-care limitation, 3.0% had an independent living limitation, 1.9% had a hearing limitation, 2.1% had a vision limitation, and 3.6% reported an ambulatory limitation.

Table 1.

Age-adjusteda prevalence of demographic characteristics of adults 18–49 years of age: 2009–2011 National Health Interview Survey

Age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population

bPercentages are weighted and may not total 100% in each category due to rounding.

CI = confidence interval

HS = high school

GED = general educational development

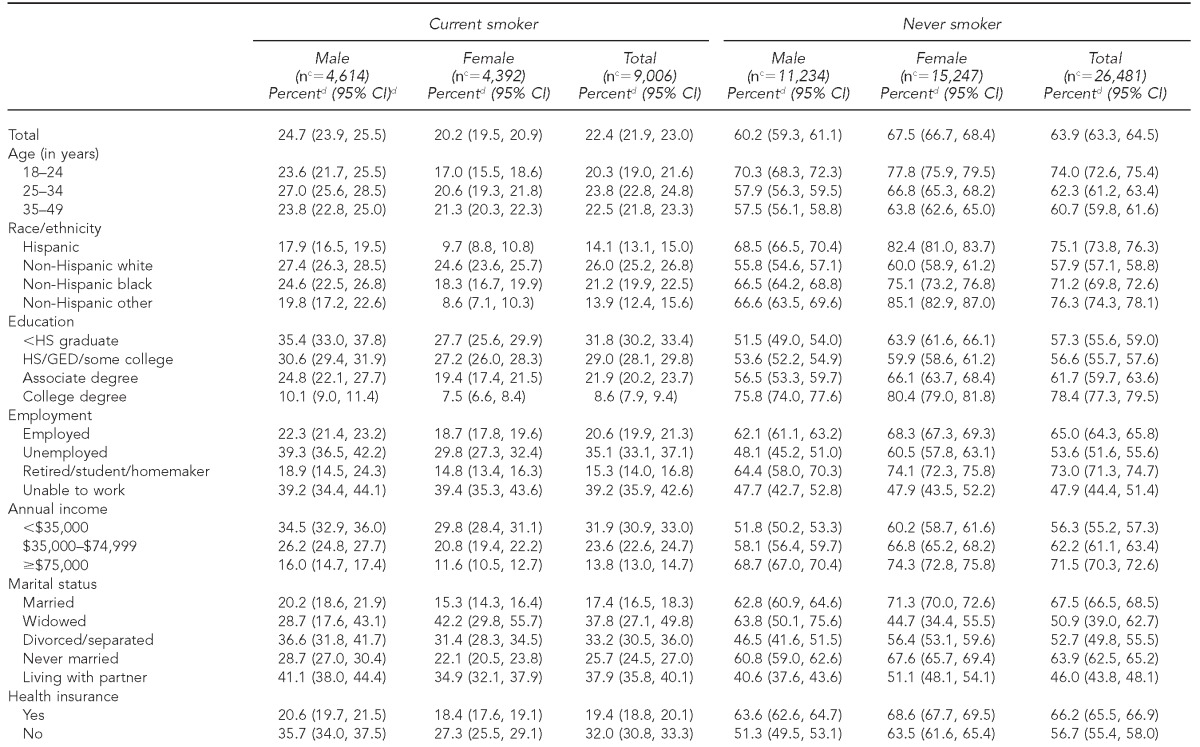

Men (24.7%) were more likely than women (20.2%) to report being a current smoker. Adults who were unable to work (39.2%) or unemployed (35.1%) were more likely to smoke than those who were employed (20.6%) or either retired, a student, or a homemaker (15.3% collectively). Those who were living with a partner (37.9%) or widowed (37.8%) were more likely to smoke than those who were married (17.4%). A higher prevalence of smoking was also seen among those who had an annual household income of <$35,000 (31.9%) compared with those who had an annual income of ≥$75,000 (13.8%), and those who had less than a high school education (31.8%) compared with those who had a college degree (8.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Age-adjusteda prevalence of current smoking or having never smoked,b by demographic characteristic and sex, including disability type, among adults 18–49 years of age: 2009–2011 National Health Interview Survey

Age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population

Can obtain estimates for former smokers by adding the estimates for current smoker and never smoker, then subtracting that from 100

cThe number reflects the number of respondents who are in that smoking category and gender.

dPercentages are weighted.

eNo statistically significant difference compared with adults without a disability. All other comparisons between disability type and no disability, for both current and never smokers, were statistically significantly significant at p≤0.001.

CI = confidence interval

HS = high school

GED = general educational development

Overall, adults with a disability were more likely than adults without a disability to be current smokers (38.8% vs. 20.7%; p<0.001). Smoking prevalence for each type of disability was significantly higher (p<0.001) than for adults without a disability, with the exception of self-care limitation among men. The prevalence of smoking by disability type ranged from 32.4% (self-care limitation) to 43.8% (cognitive limitation). Only the difference between adults with a self-care limitation and those with a cognitive limitation was statistically different (Table 2).

By sex, 39.5% of males with a disability and 38.1% of females with a disability were current smokers. The range for smoking prevalence by disability type ranged from 36.3% (hearing limitation) to 44.8% (cognitive limitation) for women, while the variation was wider for men. Men with a self-care limitation were less likely to be a current smoker (27.5%) than were men with any sensory limitation (41.4%), a cognitive limitation (42.9%), or a vision limitation (44.9%) (Table 2).

Adults with a disability (47.9%) were less likely than adults without a disability (65.6%) to report having never smoked. The prevalence of never smoking ranged by disability type from 43.5% (cognitive limitation) to 52.9% (self-care limitation). Furthermore, the prevalence of never smoking in each disability category was significantly lower than for people without a disability (61.8% for men; 69.4% for women), with the exception of self-care limitation among men (58.1% vs. 61.8%). By marital status, the lowest prevalence of never smoking was seen among those who were living with a partner (46.0%); and by employment status, among those who were unable to work (47.9%). The highest prevalence of never smoking was seen among those who were college graduates (78.4%) compared with other education levels; and those who were Hispanic (75.1%) or of another race/non-Hispanic (76.3%) compared with non-Hispanic white people (57.9%) (Table 2).

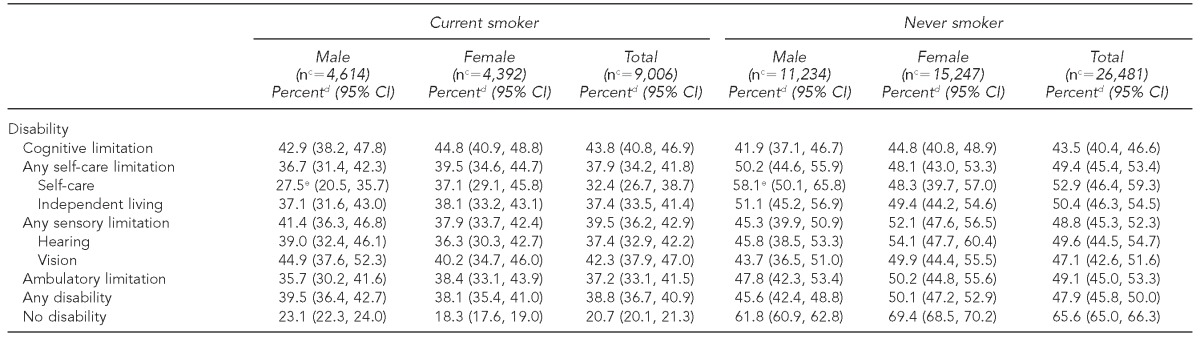

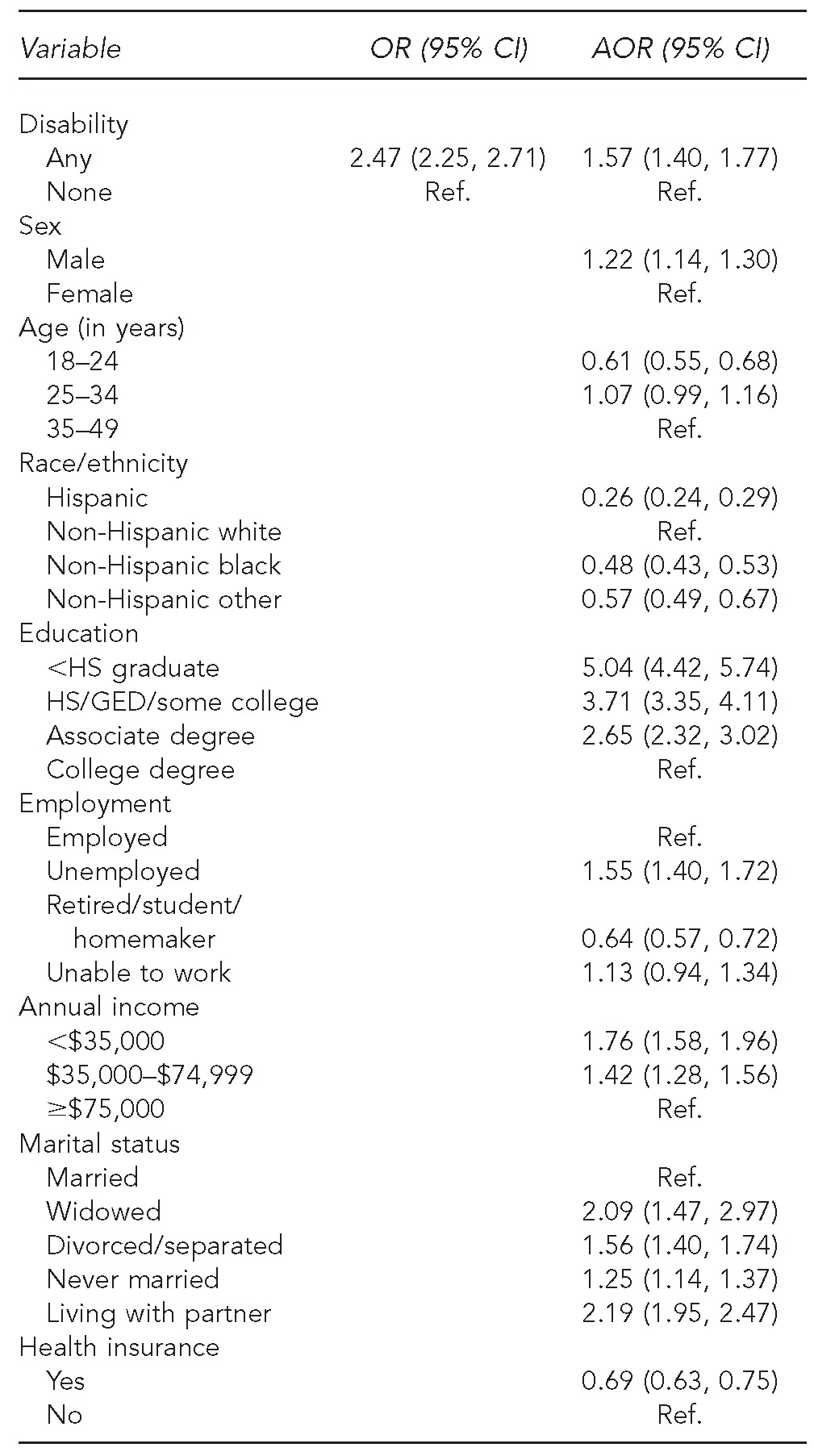

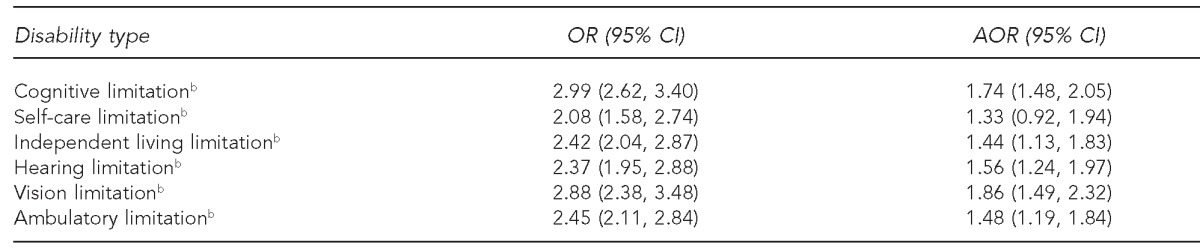

ORs for being a current smoker were statistically significantly higher for overall disability (OR=2.47; 95% CI 2.25, 2.71) and all disability types (ORs ranging from 2.08 to 2.99) compared with adults without a disability (Tables 3a and 3b). After adjusting for covariates, having any disability was associated with being a current smoker (adjusted OR [AOR] = 1.57; 95% CI 1.40, 1.77). Adults with a cognitive limitation (AOR=1.74; 95% CI 1.48, 2.05), a vision limitation (AOR=1.86; 95% CI 1.49, 2.32), a hearing limitation (AOR=1.56; 95% CI 1.24, 1.97), an ambulatory limitation (AOR=1.48; 95% CI 1.19, 1.84), or an independent living limitation (AOR=1.44; 95% CI 1.13, 1.83) had higher odds of current smoking than those without any disability. Income, education, and race/ethnicity were significant variables in the adjusted models (Table 3a). We also ran parallel models with current smoking vs. never smoking as our dependent variable, and our results were similar.

Table 3a.

Results of unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression modelsa for overall disability and the odds of being a current smoker among adults 18–49 years of age: 2009–2011 National Health Interview Survey

Adjusted models control for sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, income, marital status, and health insurance.

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

Ref. = reference group

HS = high school

GED = general educational development

Table 3b.

Results of unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression modelsa for disability types and odds of being a current smoker among adults 18–49 years of age: 2009–2011 National Health Interview Survey

Adjusted models control for sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, income, marital status, and health insurance.

bThe reference group is adults without a disability.

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

DISCUSSION

Our findings show that adults 18–49 years of age with a disability had a smoking prevalence that was nearly two times higher than adults without a disability, which supports previous findings.10,24 For example, one study found that in 2004, 29.9% of adults 18 years of age or older with a disability were current smokers compared with 19.8% of adults without a disability,10 while another study using 2001–2005 data found that 56.0% of adults with a disability vs. 43.6% of those without a disability have ever smoked.24 However, these studies used data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), in which the operational measure of disability, age group, and years studied was different than what we used in our study. Disability is often defined using BRFSS data as having an activity limitation due to a physical, mental, or emotional problem or the use of special equipment10 and does not allow for further stratification by disability type.

Generally, the results of our multivariate models were consistent with our prevalence estimates for overall disability and disability type. In addition, our findings for covariates in the model, including sex, age, race/ethnicity, income, and education, were consistent with previous research.20 Among older adults with cataracts or macular degeneration, current smokers are more likely than former smokers or nonsmokers to report visual impairment.25 Some studies have found a more rapid cognitive decline or increased risk of memory problems among smokers.19,26,27 A higher prevalence of smoking has previously been shown to be associated with mental illness.28 However, the question used to determine cognitive limitation asks about thinking, remembering, and concentrating. While these limitations could be caused by mental illness, the question does not directly measure it. Smoking is also known to cause conditions such as heart and lung disease,3 which may also be related to a lowered ambulatory function29 through decreased activity tolerance. Prior research has also found that smoking cessation may be associated with an increased recovery from some mobility impairment.29 Given the associations we found between smoking and four of the disability types in a younger cohort, and the potential for increased health improvement after cessation, additional research is warranted. Furthermore, the statistical nonsignificance of the ORs for self-care limitation could be due in part to the lower number of adults with these limitations in this age group, or because these adults may be more reliant on a caregiver or family member for daily tasks and may not have ready access to cigarettes.

Research has shown that the younger the person is when smoking cessation occurs, the greater the benefit in terms of reducing mortality22 and the risk of smoking-related conditions, including heart and lung disease.21 Although it has been shown that adults with a disability are offered cessation services at a similar level as adults without a disability,10 there is no information available in terms of use and awareness of cessation services by disability type.30 In addition, we do not know how many respondents who identified as current smokers may have quit and then relapsed later. These are directions for future work. However, the knowledge that adults with sensory, cognitive, and ambulatory disabilities continue to have higher odds of smoking provides even more directed information in terms of targeting cessation services. For example, printed information on smoking cessation services must be in an accessible format (e.g., large print) for smokers with a visual limitation and crafted at a level that can be accessible to adults with a cognitive disability. The Healthy People 2020 goal is to reduce smoking prevalence to 12% nationally.31 Given that nearly one in 10 adults aged 18–49 years has a disability and the high prevalence of smoking among them, targeted cessation interventions among this subpopulation are important to help achieve this goal.

Previous research has found that those in the general population who have low education or income levels are more likely to be current smokers than those with higher education or income levels.1,20 Our study supported these findings among younger adults. However, the combined effect of this relationship is unknown for people with disabilities. People with disabilities have been shown to be disproportionately poor and have lower education levels than those without disabilities.5 With the exception of self-care limitation, we found that people with all types of disabilities had statistically significantly higher odds of being a current smoker than adults without disabilities, controlling for income, education, and employment. What is unknown is the magnitude of the relationship among income, education, disability, and smoking and the causality or impact of each. This relationship was beyond the scope of this study and is an area of future work.

Limitations

Several areas of our study require careful interpretation, and the study was subject to several limitations. First, the NHIS is a cross-sectional dataset; therefore, we were limited in establishing causality between smoking and disability. It is possible that the disability could have been caused by smoking, or the experience of having a disability may have contributed to the person smoking or not wanting to quit. In addition, other stressors associated with disability, such as being in poverty, may contribute to smoking. However, regardless of whether smoking caused the disability or vice versa, it is important to recognize the increased prevalence of smoking among people with disabilities in this age range to better target cessation activities.

Second, we did not have any information related to duration, permanence, or underlying medical conditions of the disability. It is possible that smoking may be associated with all of these factors. Additionally, as four of the six questions ask if the limitation is “serious,” the estimate of disability was likely conservative in that it did not include adults who have moderate difficulty seeing, hearing, or concentrating, or a movement-related difficulty that does not include walking or climbing stairs. Because the NHIS surveys the noninstitutionalized U.S. population, our results may not be representative of all people with disabilities, particularly those living in congregate care settings or institutions.

Third, these results cannot be generalized to adults 50 years of age or older. Fourth, the information may be subject to reporting or recall bias, as it was either self-reported or provided by a household or family member. However, previous studies have shown that smoking estimates based on biochemical data are comparable with self-reported data.32 Finally, although we reported prevalence estimates of never smoking, we did not compare never vs. former smokers.

CONCLUSION

Findings from this study highlight the importance of measuring the prevalence of cigarette smoking among adults 18–49 years of age by type of disability. Public health intervention efforts, particularly health promotion programs, are likely to fail when there is little or no consideration for segments of the target population.33 These findings can help inform policy makers and guide program developers to develop -cessation materials that are inclusive of, and accessible to, people with disabilities.

Footnotes

This study used a publicly available dataset of de-identified data. Therefore, institutional review board approval was unnecessary.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(35):1135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Rockville (MD): HHS, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2010. A report of the Surgeon General: how tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Washington: HHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health (US); 2004. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brault MW. Current Population Reports. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2012. Americans with disabilities: 2010; pp. P70–131. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson WL, Armour BS, Finkelstein EA, Wiener JM. Estimates of state-level health-care expenditures associated with disability. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:44–51. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Racial/ethnic disparities in self-rated health status among adults with and without disabilities—United States, 2004–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(39):1069–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Rockville (MD): HHS, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2005. The Surgeon General's call to action to improve the health and wellness of persons with disabilities. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brawarsky P, Brooks DR, Wilber N, Gertz RE, Jr, Klein Walker D. Tobacco use among adults with disabilities in Massachusetts. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 2):ii29–33. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_2.ii29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armour BS, Campbell VA, Crews JE, Malarcher A, Maurice E, Richard RA. State-level prevalence of cigarette smoking and treatment advice, by disability status, United States, 2004. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4:A86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arday DR, Milton MH, Husten CG, Haffer SC, Wheeless SC, Jones SM, et al. Smoking and functional status among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:234–41. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(16):421–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchinson D, Shepstone L, Moots R, Lear JT, Lynch MP. Heavy cigarette smoking is strongly associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), particularly in patients without a family history of RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:223–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.3.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2012. Data file documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2009–2011 (machine-readable data file and documentation) [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Community Survey. Puerto Rico community survey: 2009 subject definitions. [cited 2012 Mar 15]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/acs/www/Downloads/data_documentation/SubjectDefinitions/2009_ACSSubjectDefinitions.pdf.

- 16.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2001. International classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF) [Google Scholar]

- 17.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.3 for Windows. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.RTI Inc. SUDAAN®: Release 11.0. Research Triangle Park (NC): RTI Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2001. Jan, Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2010 Statistical Notes, No. 20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ. Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:269–78. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Washington: HHS, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1990. [cited 2011 Jul 20]. The health benefits of smoking cessation: a report of the Surgeon General. Also available from: URL: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBCT.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–28. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thun MJ, Myers DG, Day-Lally C, Namboodiri MM, Calle EE, Flanders WD, et al. National Cancer Institute. Monograph 8: changes in cigarette-related disease risks and their implications for prevention and control. Washington: National Cancer Institute; 1997. Age and the exposure-response relationships between cigarette smoking and premature death in Cancer Prevention Study II. Chapter 5; pp. 383–413. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker H, Brown A. Disparities in smoking behaviors among those with and without disabilities from 2001 to 2005. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25:526–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Kahende J, Fan AZ, Barker L, Thompson TJ, Mokdad AH, et al. Smoking and visual impairment among older adults with age-related eye diseases. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards M, Jarvis MJ, Thompson N, Wadsworth ME. Cigarette smoking and cognitive decline in midlife: evidence from a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:994–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabia S, Marmot M, Dufouil C, Singh-Manoux A. Smoking history and cognitive function in middle age from the Whitehall II study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1165–73. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness—United States, 2009–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(5):81–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Østbye T, Taylor DH, Jr, Krause KM, Van Scoyoc L. The role of smoking and other modifiable lifestyle risk factors in maintaining and restoring lower body mobility in middle-aged and older Americans: results from the HRS and AHEAD. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:691–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Goldstein MG, Gritz ER, et al. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services (US), Public Health Service, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020 summary of objectives: tobacco use. [cited 2011 Jul 15]. Available from: URL: http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/TobaccoUse.pdf.

- 32.Caraballo RS, Giovino GA, Pechacek TF, Mowery PD. Factors associated with discrepancies between self-reports on cigarette smoking and measured serum cotinine levels among persons aged 17 years or older: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:807–14. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slater MD. Choosing audience segmentation strategies and methods for health communication. In: Maibach EW, Parrot RL, editors. Designing health messages: approaches from communication theory and public health practice. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 186–98. [Google Scholar]