Abstract

Although there has been much interest in estimating histories of divergence and admixture from genomic data, it has proved difficult to distinguish recent admixture from long-term structure in the ancestral population. Thus, recent genome-wide analyses based on summary statistics have sparked controversy about the possibility of interbreeding between Neandertals and modern humans in Eurasia. Here we derive the probability of full mutational configurations in nonrecombining sequence blocks under both admixture and ancestral structure scenarios. Dividing the genome into short blocks gives an efficient way to compute maximum-likelihood estimates of parameters. We apply this likelihood scheme to triplets of human and Neandertal genomes and compare the relative support for a model of admixture from Neandertals into Eurasian populations after their expansion out of Africa against a history of persistent structure in their common ancestral population in Africa. Our analysis allows us to conclusively reject a model of ancestral structure in Africa and instead reveals strong support for Neandertal admixture in Eurasia at a higher rate (3.4−7.3%) than suggested previously. Using analysis and simulations we show that our inference is more powerful than previous summary statistics and robust to realistic levels of recombination.

Keywords: ancestral admixture, D statistic, maximum likelihood, Neandertal introgression

WHOLE-GENOME sequence data have made it feasible to detect low levels of ancestral admixture between recently diverged populations and species even from few individuals. An increasing number of genome-wide analyses are uncovering signatures of introgression between sister species in a large range of taxa (Kulathinal et al. 2009; Lawniczak et al. 2010; Heliconius Genome Consortium 2012; Cui et al. 2013; Eaton and Ree 2013; Martin et al. 2013), suggesting that reticulations may be an ubiquitous feature of speciation. Similar evidence for gene flow after divergence has been found in hominid lineages (Patterson et al. 2006). A number of recent studies analyzing the Neandertal genome have suggested that admixture also occurred in the genus Homo (i.e., from Neandertals and other archaic lineages into modern Eurasian populations) following the expansion of modern humans out of Africa (Green et al. 2010; Sankararaman et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2012).

To test for admixture between Neandertal and Eurasian populations, Green et al. (2010) have developed a simple summary statistic. The D statistic assesses the fit of a strictly bifurcating species tree. For a triplet of African, Eurasian, and Neandertal genomes, and an outgroup (chimpanzee), in which the underlying species tree is [(African, Eurasian), Neandertal], incomplete lineage sorting leads to two diagnostic site patterns. Denoting the ancestral state at a polymorphic site as A and the derived state as B, mutations incongruent with the species tree may either be “ABBA” (i.e., shared by Eurasian and Neandertal) or “BABA” (shared by African and Neandertal). Given the inherent symmetry of coalescence in the common ancestral population under a null model of strict divergence without gene flow, the ratio D = (NABBA − NBABA)/(NABBA + NBABA) is not expected to be significantly different from 0 (Green et al. 2010; Durand et al. 2011). In contrast, an excess of either ABBA or BABA sites cannot be explained by incomplete lineage sorting, suggesting population structure or gene flow (Figure 1).

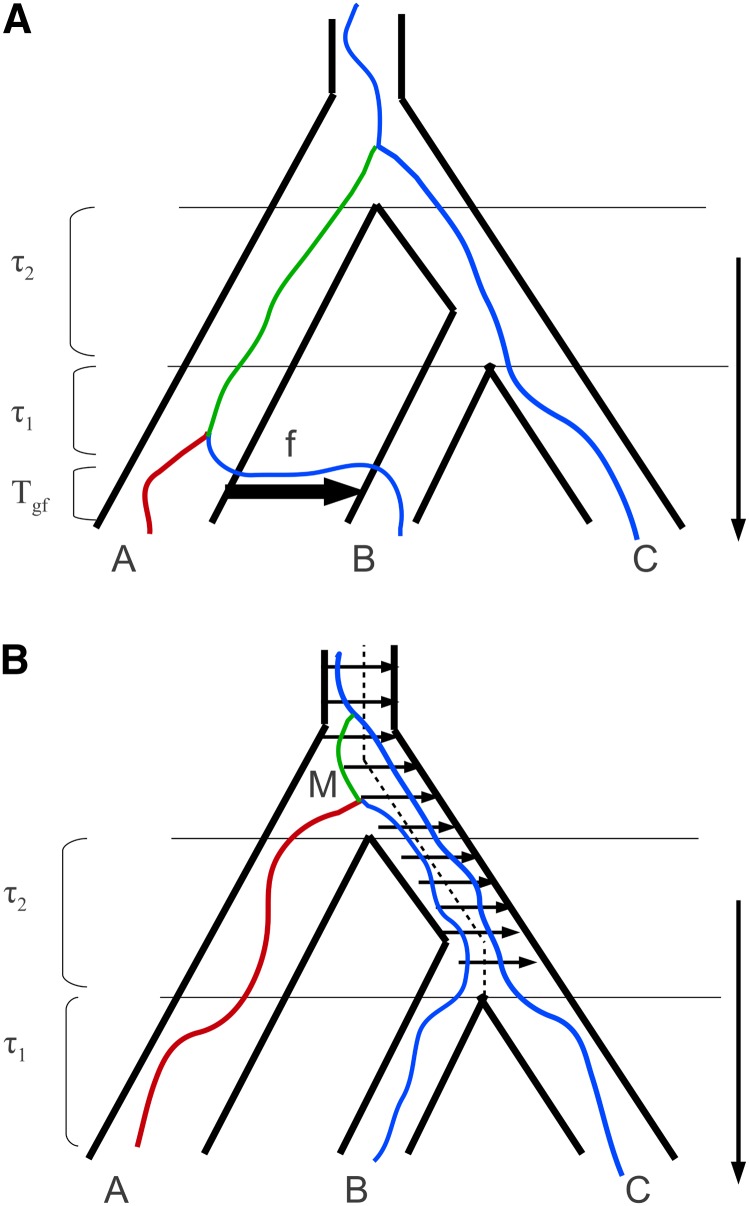

Figure 1.

Models of divergence between three populations with either (A) a recent instantaneous, unidirectional admixture event (IUA model) or (B) persistent structure in the ancestral population (AS model). Both histories lead to an excess of incongruent genealogies characterized by an internal branch tab (in green). However, the distribution of branch lengths, in particular that of the external branch ta (in red), differs between the IUA and AS models (Figure 2).

Positive D has been found and interpreted as evidence for gene flow not only in the Neandertal analysis (Green et al. 2010), but also in genome-wide studies of closely related species of Heliconius butterflies [whose origin is thought to have involved the introgression of color pattern genes (Heliconius Genome Consortium 2012; Martin et al. 2013)] and an island radiation of pigs in Southeast Asia (Frantz et al. 2013).

However, D is a drastic summary of genetic variation and, like other population genetic summary statistics such as FST, is fundamentally limited in the sense that it is not diagnostic of any specific historical scenario. In particular, Durand et al. (2011) have compared the expectation of D under a model of instantaneous unidirectional admixture (IUA) (Figure 1A) and a different divergence model, involving structure in the ancestral population (ancestral structure, AS) (Figure 1B). The AS model assumes a genetic barrier (with gene flow of M = 4Nem migrants per generation) that arises in the common ancestral population and persists until the most recent split (Durand et al. 2011). Under this model, increasing barrier strength leads to increasing topological asymmetries (Slatkin and Pollack 2008) and hence positive D. Thus a key finding of the Durand et al. (2011) analysis is that it is impossible to distinguish between gene flow after divergence and structure in the ancestral population using D. Although Green et al. (2010) argue that admixture from Neandertals into Eurasians is the most plausible history, they conclude that “we cannot currently rule out a scenario in which the ancestral population of present-day non-Africans was more closely related to Neandertals than the ancestral population of present-day Africans due to ancient substructure within Africa” (Green et al. 2010, p. 722). This has led to recent controversy about the genomic signature of Neandertal admixture. In particular, Eriksson and Manica (2012) have used approximate Bayesian computation to show that D values identical to those observed in the Neandertal–Eurasian–African triplets can be generated under stepping-stone type models of colonization and structure without admixture and recommend caution in inferring admixture from geographic patterns of shared polymorphisms. While recent studies examining patterns of linkage disequilibrium (Sankararaman et al. 2012) and allele frequency spectra of modern human populations (Yang et al. 2012) provide qualitative support for Neandertal admixture, a rigorous statistical comparison of these alternative scenarios of human history is lacking.

D captures the information contained in the mean length and frequency of two types of genealogical branches. However, given the randomness of the coalescent process, much of the signal about population history is contained in the higher moments of the distribution of branch lengths. An obvious strategy for exploiting this information is to partition the genome into short sequence blocks within which recombination can be ignored and to maximize the joint likelihood across blocks (Nielsen and Wakeley 2001; Yang 2002; Zhu and Yang 2012). Because the space of possible genealogies grows superexponentially with the number of sampled individuals, multilocus inference methods are generally computationally intensive and often rely on Markov chain Monte Carlo methods (Nielsen and Wakeley 2001) or simulations. However, for small samples of individuals an analytic solution to the likelihood is possible (Yang 2002; Wilkinson-Herbots 2008; Wang and Hey 2010; Lohse et al. 2011), making inference from whole-genome data feasible.

In this study we compute maximum-likelihood estimates of parameters under the AS and IUA models from three genomes. We first show how the generating function (GF) of branch lengths can be used to derive the probability of full mutational configurations in short sequence blocks under both models. We then investigate the power of this new method to distinguish between IUA, AS, and a null model of strict divergence and compare it with that of the D statistic. We apply the method to triplet samples of contemporary human genomes from Africa and Eurasia and the Neandertal genome sequenced by Green et al. (2010) and quantify the relative support for alternative models. Finally, we use simulations to demonstrate the robustness of our inferences to recombination.

Models and Methods

We consider a history of three populations A, B, and C that are related to each other via two divergence events. Populations B and C split from each other at time T1, and their common ancestral population in turn split from population A at a previous time T2 > T1. The IUA model further assumes an instantaneous IUA event that transfers a fraction f of lineages from population A into population B (forward in time) at a more recent time Tgf < T1 (Figure 1A). Alternatively, the AS model assumes a barrier in the population ancestral to B and C, which persists into the common ancestral population (Figure 1B). While Durand et al. (2011) assume symmetric migration across the barrier and an additional time parameter at which the barrier arises, we consider a slightly simpler model with a permanent barrier (Slatkin and Pollack 2008) and unidirectional gene flow (with M/2 migrants per generation).

Going backward in time, we can describe the history of a sample X = {a, b, c} as a discrete-time Markov chain. We need to trace both the location and the coalescence of the sample as well as the merging of the three populations backward in time (corresponding to splits forward in time). Fixing the order of populations as A, B, and C and using / to separate them, we can denote the initial state at the time of sampling (*a/b/c) (where the asterisk indicates that the admixture event is still pending). Under the IUA model, there are a further 10 states: (a, b/∅/c), ({a, b}/∅/c), (a, b/c), ({a, b}/c), (a/b, c), (a/{b, c}), (a, {b, c}), (b, {a, c}), (c, {a, b}), and (a, b, c). We use {a, b} to denote a new lineage generated by a coalescence event between a and b and (a, b/∅/c) to denote a state where population B is empty (because lineage b has traced back to population A).

Assuming an infinite-sites mutation model and an outgroup to polarize mutations, the polymorphism information in a sample of sequences X can be summarized by counting the number of mutations on each possible genealogical branch as a vector k with entries kS, where S ⊆ X. For X = {a, b, c} there are six mutation types: k = {ka, kb, kc, kab, kac, kbc}, where ka is the number of mutations found only in sample a, kab is the number of mutations shared by a and b, and so on. Shared derived mutations uniquely define a topology: all genealogies have a terminal branch contributing to ka, but only genealogies with topology Gab contribute to kab. We are interested in computing P[k|Θ], the probability of a mutational configuration k given parameter values Θ under either the IUA or the AS model. P[k|Θ] can be interpreted as the likelihood of the model. In principle, this can be found as

| (1) |

where P[t|Θ] is the joint distribution of genealogical branches and P[k|t, μ] the probability of a mutational configuration given a genealogy t and mutation rate μ. This decomposition of the likelihood was first outlined by Felsenstein (1988) and has been used to derive likelihoods for minimal samples under a number of models: Yang (2002) studies a divergence model involving three populations and Wilkinson-Herbots (2008) and Wang and Hey (2010) study a model of isolation with migration between two populations. P[t|Θ] can be found as a convolution of the waiting times between all successive sample states. However, this direct approach quickly gets out of hand given the large number of possible histories of the sample that need to be considered and because the integral in Equation 1 has as many dimensions as there are genealogical branches and so is hard to solve.

Here we use the GF or Laplace transform of P[t] to derive P[k] under the IUA and AS models. The general approach has been described in detail by Lohse et al. (2011). Below, we give a brief summary of the main steps involved and derive several genealogical quantities under the IUA and AS model that help understand how these scenarios can be distinguished.

Computing likelihoods from the generating function

The GF of the distribution of branch lengths P[t] is defined as ψ[ω] = E[e−t·ω], where the vector of dummy variables ω corresponds directly to the branch lengths t and mutation counts k. As Lohse et al. (2011) show, for a general class of models in which the waiting times between successive states in the history of a sample are exponentially distributed, the GF has a simple recursive form that relates the sample state at a particular time, Ω, to the state Ωi before some event i (which may be coalescence, population divergence, or admixture) (Lohse et al. 2011, equation 4):

| (2) |

The denominator is given by the total rate of events plus the sum of dummy variables ωS corresponding to the genealogical branches that increase during this interval. For the first event, these are the “leaves” of the genealogy, i.e., |S| = 1. The numerator is a sum of the GFs of all possible previous states, each weighted by the rate of the corresponding event λi.

To be able to apply this recursion to the IUA model, we initially assume that the intervals between population split and admixture times (τ1, τ2, and Tgf in Figure 1A) are exponentially distributed with rates Λ1, Λ2, and Λgf. The GF equations for this continuous analog of the IUA model are easy to write down and (using Mathematica) solve. For instance, consider the GF for the initial state of the sample (∗a/b/c). The only possible event is admixture (which occurs with rate Λgf). This leads either to state (a, b/∅/c) if the lineage in population B traces back to population A (with probability f) or to state (a/b/c) if it remains in population B (with probability 1 − f). The GF term is

Once admixture has occurred, we allow for the merging of populations B and C (at rate Λ1) and finally the merging of population A and the population ancestral to B and C (at rate Λ2). The GF terms for all sample states under the IUA model and their solution are given in the Appendix.

We denote the GF for the original model with discrete population split and admixture times P[ω]. Noting that (Lohse et al. 2011, 2012), P[ω] can be obtained by multiplying ψ[ω] by (ΛgfΛ1Λ2)−1 and inverting once for each event with respect to the corresponding Λ parameter.

We can partition P[ω] into contributions from the three different topologies by setting GF terms in the recursion that involve branches that are incompatible with a particular topology to zero. Note that P[ω] = P[ω, Gbc] + P[ω, Gac] + P[ω, Gab] (Lohse et al. 2011). This is convenient because the GF for a particular topology depends only on the intervals between the two coalescence events. For example, for topology Gab we can define corresponding dummy variables ω3 = ωa + ωb + ωc and ω2 = ωc + ωab (labeled by the number of lineages during each interval). Using this simplification gives relatively compact expressions (Equation A1, Appendix).

Lohse et al. (2011) show that under an infinite-sites mutation model with a uniform mutation rate θ/2 = 2Neμ, the probability of a particular mutational configuration can be found by taking successive derivatives of the GF (Equation A1) with respect to the relevant ω variables (Lohse et al. 2011, 2012). Specifically, the probability of k3 and k2 mutations in the two coalescence intervals is

| (3) |

We can compute P[k] from the above by considering the possible ways the mutations on each branch can fall into the two coalescent intervals (Lohse et al. 2011). For example, for topology Gab, we have

| (4) |

This uses the fact that, for a given topology, mutations on the two shorter external branches (e.g., ka and kb for Gab) can be combined because the underlying branches have the same length.

The logarithm of the likelihood (lnL) for a data set consisting of an arbitrary number of sequence blocks is simply the sum of lnL across blocks. The joint lnL can be maximized using the Mathematica function FindMaximum, which takes a few minutes on a modern personal computer. We restricted the computation of exact probabilities to configurations that involve up to a maximum of km = 3 mutations on any one genealogical branch. The probabilities of rare configurations with more than km mutations on one or several branches can also be calculated from the GF by considering the relevant marginal probabilities (see Supporting Information, File S1). Code for the likelihood computation for the IUA and AS models is implemented in Mathematica (Wolfram Research 2010) (File S1).

Genealogical properties

We can use the GF to derive several useful genealogical quantities under the IUA and AS model. First, the probability of each topology can be found by setting all ω terms in Equation A1 (Appendix) to 0. For the IUA model this gives

| (5) |

An alternative derivation of Equation 5 can be made using discrete-time transition matrices (analogous to Slatkin and Pollack 2008; Lohse 2010).

Second, the moments of the length of a particular branch can be found from the GF by taking derivatives with respect to the corresponding ω variable. For example, the expected lengths of the two incongruent branches are and Multiplying by θ/2 gives the expected number of the two incongruent types of shared derived mutations kab and kac. These are Pr(ABBA) and Pr(BABA) in the notation of Durand et al. (2011, equations 3 and 4).

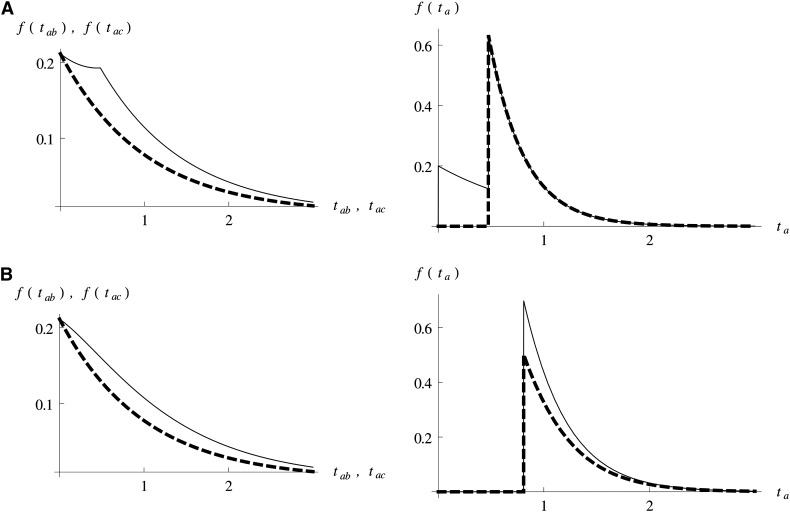

Finally, to find the length distribution for a particular branch, we invert the GF with respect to the corresponding ω variable (using Mathematica). Figure 2 contrasts the distributions of branches tab, tac, and ta under the IUA and AS models.

Figure 2.

The length distribution of the internal branches tab (colored in green in Figure 1) and tac that specify genealogies that are incongruent with the order of population divergence and the shorter external branch ta (colored in red in Figure 1) under (A) the admixture (IUA) model or (B) a model of ancestral structure (AS) (Figure 1). Branch length distributions for genealogies with topologies tab (the frequency of which is increased by admixture or population structure) are shown as solid lines and those for the alternative incongruent topology tac as dashed lines. A is based on the parameters of Durand et al. (2011) with high admixture (f = 0.2); the parameters in B are chosen to give the same expected D value.

Power analyses

For ease of comparison, we focus on the IUA history previously studied by Durand et al. (2011): Tgf = 2500, T1 = 3000, T2 = 12,000, and f = 0.04. Assuming Ne = 10,000 (fixed for all populations) these roughly match the history previously inferred for Neandertals and African and Eurasian Homo sapiens by Green et al. (2010). All time parameters are in generations; corresponding values scaled in 2Ne generations are given in Table S1.

Given j possible mutational configurations kj and a true history Θ1, the expected difference in support, i.e., E[Δ lnL] between the true model Θ1 and an alternative history Θ2, can be computed as

| (6) |

where denotes the set of parameter values that maximize lnL under a particular model. Analogously, the accuracy of the likelihood method to estimate a particular model parameter θ can be quantified using Fisher information, which is defined as and measures the sharpness of the lnL curve near the maximum (Edwards 1972). The average information about a parameter contained in a sequence block is given by summing I over all mutational configurations j weighted by their probability:

| (7) |

The expected information in a data set consisting of n sequence blocks is simply n × E[I]. Assuming parameter values are away from the boundaries, the inverse of I gives a lower bound on the variance (and covariance) of parameter estimates (Rao 1945).

Application to human–Neandertal data

We downloaded BAM files (short-read alignment) of the three Vindija bones (SLVi33.16, SLVi33.25, and SLVi33.26) that were aligned to the human genome (hg18), from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/Neandertal). We used only sites with a minimum mapping quality of 90 and a sequence quality of 40 and, to avoid potential duplicates, filtered out positions that were covered by more than three reads, as the genome-wide average depth of coverage was ∼1.5-fold (Green et al. 2010). We further excluded the first and last 5 bp of every read, as these positions are enriched for sequencing errors (Green et al. 2010). We also excluded transitions from the analysis to limit the effect of ancient DNA damage (Briggs et al. 2007) and used only autosomal chromosome sequence. We obtained genotype files for a European (CEU) (Coriell ID: NA06985), a Han (CHB) (Coriell ID: NA18526), and a Yoruba (YRI) (Coriell ID: NA18501) individual from complete genomics (ftp://ftp2.completegenomics.com, release 1.2). We analyzed two triplet combinations, Neandertal/Eurasian/Yoruba, where the Eurasian genome is either CEU or CHB. For the outgroup sequences, we extracted the genotype of the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and the human–chimp ancestor sequence reconstruction (available from the four primates Euredo Pecan Ortheus (EPO) alignment provided by Ensembl release 54) in 1:1 human–chimp orthologous regions for each site that was covered in the Neandertal genome. Sites were polarized (ancestral vs. derived) using the sequence reconstruction of the human–chimp ancestor. We partitioned the human genome into 5-, 10-, and 20-kb fixed length blocks. For each block, we sampled the first 2, 4, or 8 kb of sequence covered in all samples (three humans sequences, both outgroups, and the Neandertal) and discarded any block with lower coverage.

The three human genomes are from a single diploid individual, and the Neandertal genome is based on a sample of three individuals. To meet the assumption of the likelihood method of a single haploid sample per population, we phased blocks at random. Although this may seem drastic (given that only 35% of polymorphic sites are homozygous in all individuals), the potential for phasing error is small for the block length we consider for two reasons. First, there is no phasing ambiguity for blocks that contain less than two heterozygous sites in all individuals, which is true for 75% of 2-kb blocks. Second, the majority (68%) of heterozygous sites are unique to one sample but invariable in all others and so due to mutations on external branches (shown in red and green in Figure S4). Erroneous phasing of such unique heterozygous sites cannot affect the number of shared derived mutations (i.e., kab, kac, and kbc). Furthermore, with minimal sampling, the two alleles in an individual often trace back to a common ancestor via two external branches (see mutations in green in Figure S4), which have the same length. In this case, random phasing error cannot bias the number of mutations on external branches.

Violations of the four-gamete criterion within a block can arise due to recombination, back mutation, or phasing error, all of which are incompatible with our assumptions. We therefore excluded blocks that contained more than one type of shared derived mutation from the analysis (1.5%, 4.9%, and 14.2% in the 2-, 4-, and 8-kb data sets, respectively). Applying the interblock distance and filtering steps described above to the entirety of the human autosomes yielded 291,620, 146,281, and 71,940 blocks of 2, 4, and 8 kb length, respectively (File S2).

While the analysis of Green et al. (2010) focuses on shared derived sites, our likelihood computation uses all polymorphic sites. In fact, our analytic results show that much of the information to distinguish between the IUA and AS models is contained in the distribution of external branches (Figure 2). This presents a problem in practice: given the low sequence coverage of the Neandertal (1.5-fold), the vast majority of sites affected by postmortem DNA damage will be visible as (spurious) Neandertal singletons. To address this, we made a simple error correction based on the symmetry of genealogical branches. Assuming that sequencing error in the modern human data can be ignored and that the mutation rate and generation time are the same for Neandertals and modern humans, the expected proportion of true Neandertal singletons can be estimated from the difference in the total number of derived sites in the modern human and the Neandertal genome. We estimated the proportion of true Neandertal singletons as 35% and randomly subsampled Neandertal singletons in each block with this probability. Note that both this correction and our models assume that the root–tip distance is the same for all samples (ignoring the fact that Neandertals died out) and are consistent with each other. To check whether this correction could bias model and parameter estimates, we reran likelihood analyses without the Neandertal singletons (see Sensitivity analyses).

We computed maximum-likelihood estimates of parameters under the IUA model (with one or two ancestral Ne parameters), the AS model, and a null model of strict divergence. Given that the likelihood computation assumes that blocks are statistically independent, the effect of physical linkage between blocks must be accounted for. One could subsample blocks that are separated by some threshold distance lmin over which the effect of statistical associations can be ignored and then average lnL estimates over all such subsampled data sets. This is equivalent to rescaling likelihoods obtained from all the data by a factor (l/lmin), where l is the block length. We assumed that the effect of physical linkage between blocks separated by a distance >100 kb can be ignored (Sankararaman et al. 2012). This threshold was chosen to be conservative and so our confidence in model and parameter estimates gives a lower bound to linkage-aware estimates. We note that the scaling argument above can be used to adjust our results for any level of linkage.

Results

Power analyses

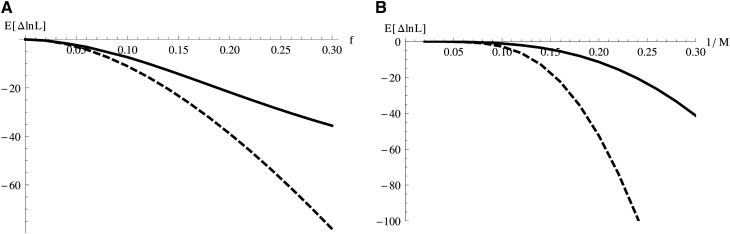

Our comparison of the likelihood method and the D statistic highlights several advantages of the maximum-likelihood scheme. First and as shown in Figure 3, the likelihood method can distinguish between admixture (IUA) and AS models regardless of which scenario is true. Second, maximum-likelihood computation from sequence blocks has greater power (as measured by E[Δ lnL]) to distinguish between the IUA history (when true) and a null model of strict divergence than D calculated from unlinked SNPs. This is true even if we set the length of blocks such that they contain a single SNP on average (Figure S1A). Finally, we can use Fisher information to quantify how informative sequence data are about a particular model parameter and hence how accurate one can expect parameter estimates to be. Under the IUA history, there is much more information about the admixture fraction f than about the time of admixture Tgf (Table S1). E.g., given a sample of 10,000 blocks of 2 kb length, one would expect a standard deviation (SD) of 0.0145 for estimates of f, but 0.178 for Tgf (Table S1). Note that in contrast to the D statistics that have been used to derive a lower bound on f (Durand et al. 2011), the maximum-likelihood estimate of f is unbiased provided the assumption of no recombination within blocks is met (see Sensitivity analyses below).

Figure 3.

(A) The expected difference in support (E[ΔlnL]) between the IUA model and the AS model (thick solid curve) and between the IUA and a null model of strict divergence (dashed curve), when IUA is true plotted against the admixture fraction f. B shows analogous results for E[ΔlnL] against barrier strength (1/M) when the AS model is true. Plots are based on analytic results for the likelihood and assuming 10,000 sequence blocks, θ = 3, and the time parameters of Durand et al. (2011, table 6).

As expected, increasing the length of sequence blocks sharpens the likelihood surface (Figure S1) and so increases the power to distinguish alternative models (Figure S1A) and the accuracy of parameter estimates (Table S1, Figure S1B).

Application to human–Neandertal data

We found that a history of recent admixture from Neandertals into Eurasians (IUA model) is better supported by both the CEU and CHB data than a null model of divergence without gene flow or a model of ancestral structure (AS, Table 1). The estimated differences in support (ΔlnL) between the null model and the IUA model were highly significant, assuming a χ2-distribution, which is conservative (Zhu and Yang 2012). Likewise, the increase in support for the IUA and the IUA2 model relative to the AS model was substantial. Allowing the size of the ancestral population between T1 and T2 to differ from that of the common ancestral population further improved the fit of the admixture model (i.e., the IUA2 model) (Table 1).

Table 1. Support ΔlnL relative to the best-fitting model (IUA2) for alternative models of history.

| Data set, kb | IUA2 (5) | IUA (4) | AS (4) | Null (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEU, 2 | 0 | 0.142 | 9.13 | 9.13 |

| CHB, 2 | 0 | 0.249 | 6.49 | 9.45 |

| CEU, 4 | 0 | 6.67 | 15.3 | 33.7 |

| CHB, 4 | 0 | 5.17 | 16.8 | 33.1 |

| CEU, 8 | 0 | 28.0 | 34.3 | 82.4 |

| CHB, 8 | 0 | 27.9 | 37.8 | 87.0 |

Shown are strict divergence (Null), divergence with admixture (IUA), and ancestral population structure (AS). The IUA2 model allows for two different ancestral Ne. The best supported model is indicated in boldface type.

To convert estimated divergence times (scaled in 2Ne generations) into absolute values, we followed Green et al. (2010) and assumed an average gene divergence time between chimps and humans of 6.5 MY and a generation time of 25 years. Given this calibration, we estimated that Neandertals diverged from the ancestor of modern humans 329–349 KYA (T2). The divergence between modern African and non-African human populations (T1) occurred 122–141 KYA. Estimates for T1 and T2 generally agreed well between the CEU and CHB analyses (Table 2, Table S2). We inferred a fraction of Neandertal admixture (f) of 5.9% and 5.3% in the CHB and CEU analyses, respectively, with 95% C.I. broadly overlapping between the two analyses (Figure S2). There was little information about the time of admixture and the 95% C.I. for this parameter included T1 in all analyses (Table 2, Table S2).

Table 2. Maximum-likelihood estimates of parameters under the divergence with admixture (IUA) model.

| Data set, kb | θ | T1 | T2 | Tgf | f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEU, 2 | 0.42 | 0.379 | 0.967 | 0.12 | 0.053 (0.034–0.073) |

| 7,012 (6,950–7,190) | 133 (124–141) | 339 (329–349) | 55.1 (0–T1) | ||

| CHB, 2 | 0.42 | 0.376 | 0.968 | 0.16 | 0.059 (0.039–0.079) |

| 7,000 (6,950–7,190) | 132 (123–140) | 339 (329–349) | 75.8 (0–T1) | ||

| 10,000 | NA | 270–440 KY | NA | 0.01–0.06 |

Time parameters are scaled in 2Ne generations and measured from the present. The second row (in boldface type) gives absolute parameter values, i.e., effective population sizes in individuals and divergence in KY. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (in parentheses) were calculated assuming that LD between blocks >100 kb apart can be ignored. Estimates by Green et al. (2010) and Durand et al. (2011) are shown for comparison in the last row.

Sensitivity analyses

In practice, the assumption of no intralocus recombination limits multilocus analyses to relatively short blocks. Thus, the usefulness of our method clearly depends on the relative rates of recombination and mutation and the heterogeneity of both processes along the genome. There is a trade-off between power and bias: if blocks are too short, they contain little additional information compared to SNP frequency spectra. Making blocks excessively long on the other hand potentially biases parameter estimates because recombination within blocks reduces the variance in inferred branch lengths (Hudson and Kaplan 1985) and blocks with detectable recombination breakpoints (four-gamete criterion) are excluded. We investigated the effect of intralocus recombination on parameter estimates in two ways.

First, we repeated all analyses with longer (4 and 8 kb) blocks. Reassuringly, increasing block length did not change the relative support for alternative models (Table 1). However, as expected from the analytic results (Table S1 and Figure S1), using longer blocks increased power (Table 1). Although in general, parameter estimates were little affected by block length (Table 1, Table S2, and Figure S2), we observed some subtle shifts that are consistent with the known effects of recombination (Wall 2003): estimates of divergence and admixture times increased, whereas ancestral Ne decreased with block length (Table S2). However, some of these shifts may at least be partially due to phasing error (which also increases with block length). Second, we quantified the bias in parameter estimates due to intralocus recombination by testing the maximum-likelihood method on data simulated with realistic levels of recombination. We used ms (Hudson 2002) to simulate data under the best-fitting model (estimated from the 2-kb CEU data, Table 2) for varying block lengths (1–8 kb) and assuming a recombination rate of 1.3 cM/Mb. Our robustness analyses confirmed that ignoring recombination within loci resulted in a slight upward bias of divergence times and a downward bias of ancestral Ne, as expected (Wall 2003). Importantly, however, these effects were small for the block sizes considered (Figure S3).

To investigate the effect of our correction for Neandertal singletons, we reran the likelihood inference without Neandertal singletons (by removing them from the data and setting the mutation rate on the Neandertal branch to zero). Reassuringly, this did not alter our main finding of greater support for the IUA compared to the AS model (Table S3). In fact, the difference in support (ΔlnL) between these models increased slightly. Likewise, parameter estimates were little affected (Table S4). However, we found that without Neandertal singletons, there was virtually no information to estimate Tgf. This is perhaps unsurprising given that the ability to estimate this most recent event should be disproportionally influenced by the removal of an external branch and because there is already very little information on this parameter in the full data set.

Our analysis ignores mutational heterogeneity across loci. To test whether this could affect inference, we partitioned 2-kb blocks into 10 bins of equal size according to their relative distance to the chimpanzee. Incorporating relative mutation rates for each bin resulted in lower support overall but little change in parameter estimates (not shown).

To check how well the data fitted the inferred history overall, we compared the observed distribution of the total number of mutations (S) in each topology class with its expectation. Table S5 shows a close match between observed and expected frequencies of blocks. The only notable disagreements are a slight excess of topologically resolved blocks (2%) and a subtle excess of blocks that have an incongruent topology {e.g., [YRI, (N, CEU)] or [CEU, (N, YRI)]} and a shallow genealogy in the real data (see S = 1 in Table S5). This may be a result of selective constraints on some sequences, which are not captured by our method.

Discussion

We have developed a method to fit alternative models of divergence between three populations with either recent gene flow or ancient structure to genomic data. We show that partitioning the genome into short blocks within which recombination can be ignored gives an efficient way to compute genome-wide maximum-likelihood estimates under these models. The robustness of this approach to recombination is highlighted both by our sensitivity tests on simulated data (Figure S4) and by the agreement of parameter estimates across a range of block sizes (Table S2). The latter also suggest that the potential effects of phasing error (which increases with block size) are small for the block sizes we consider. Clearly, treating nearby SNPs as linked over short distances is a realistic approximation that adds substantial information to historical inference.

Our maximum-likelihood scheme has several advantages over the D statistic (Green et al. 2010; Durand et al. 2011): first, it is statistically optimal in the sense that all available information is used and therefore has greater power. Second, instead of testing a null model, one obtains joint estimates of all relevant parameters under a set of alternative models. This constitutes an improvement over previous genomic analyses that generally have estimated divergence and admixture parameters separately and using different approaches. Finally, and in contrast to the assertion of Durand et al. (2011, p. 2250) that distinguishing between ancestral admixture (IUA) and population structure (AS) “[…] will require using more than one sample per population”, our analysis shows that the two scenarios can be distinguished using minimal samples. Considering the difference in the length distribution of branches between these models (Figure 2), it is clear where the signal comes from. While the length distribution of internal branches differs only subtly between the two models, there is a marked difference in the distribution of external branches: incongruent genealogies with short external branches (i.e., ta < T1) are possible under the IUA model, but not under the AS model (compare Figure 2A and B).

Conclusions About Human History

Our analysis of human–Neandertal data provides strong statistical support for the IUA model and confirms previous claims that Neandertals contributed genetically to contemporary Eurasian populations (Green et al. 2010; Sankararaman et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2012). However, in contrast to previous studies we can conclusively reject long-term population structure in the ancestral African population as an alternative explanation for the excess sharing of derived mutations by Neandertals and Eurasians.

The parameter estimates we infer agree well with a number of recent population genomic studies on human history (Green et al. 2010; Sankararaman et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2012; Wall et al. 2013). For example, our population divergence times match those of Green et al. (2010) and the ancestral population size is close to the average Ne inferred by Li and Durbin (2011) during that period (120–500 KY). Similarly, our inference of a slightly higher fraction of Neandertal admixture in the Han compared to the European genome (Table 2 and Table S2) mirrors recent findings based on comparing average D in Asian and European individuals (Wall et al. 2013).

It is notable that we infer a larger fraction of Neandertal admixture (3.4% > f > 7.9%) than previous studies [1–6% (Green et al. 2010; Durand et al. 2011)]. However, this difference is to be expected given that the D-based estimator is a lower bound of f (Durand et al. 2011). While our exploration of simulated data shows that ignoring recombination within blocks slightly biases f estimates upward, potentially leading to larger f estimates for longer blocks (Figure S3), we observe little such bias in the Neandertal analysis (Figure S2 and Figure S3). We also reiterate the point made by Durand et al. (2011) that f estimates are rather sensitive to assumptions about the effective population sizes of Neandertals. We have followed Durand et al. (2011) in assuming that the Ne of Neandertals equals that of the common ancestral population. It will be interesting to incorporate information about the Ne of Neandertals into such analyses in the future.

Although in principle our method allows us to estimate the time of admixture Tgf and our estimates for this parameter encompass those of Sankararaman et al. (2012) (37–86 KY), our power analysis shows that multilocus data contain very little information about this parameter (Table S1). This makes intuitive sense, considering that only mutations that arise between Tgf and T1 contribute information about this parameter. Methods that use information contained in patterns of linkage (Sankararaman et al. 2012; Ralph and Coop 2013) are more informative over such recent timescales.

In conclusion, we show that maximum-likelihood calculations on blocks of sequences allow for a joint estimation of divergence times, ancestral effective population sizes, and the fraction and time of admixture. This approach has greater power than summary statistics and can distinguish between subtly different scenarios of admixture and ancestral population structure. Our results allow us to conclusively reject the ancestral structure model and demonstrate that secondary admixture from Neandertals into Eurasians took place after the expansion of modern humans out of Africa. This has important implications for our understanding of human evolution. Future studies, based on ancient and/or modern DNA, will likely shed light on the frequency at which such reticulation events took place in the hominin lineage. Because our approach maximizes the information contained in individual genomes, it will be particularly useful for revealing the history of rare and extinct species and populations for which samples are limited. Another advantage of considering minimal samples is that it renders inferences of ancestral parameters robust to the details of more recent demographic events that would otherwise need to be modeled explicitly. Given that the analytic basis of our method is not restricted to any particular model (Lohse et al. 2011), it should be possible to develop analogous calculations for other histories and incorporate recombination or useful approximations such as the sequential Markov coalescent (McVean and Cardin 2005) in these inferences in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Barton and Stuart Baird for discussions and comments and Lynsey Bunnefeld for assistance with simulations. Helpful comments from Joshua Schraiber, Nick Patterson, Ed Green, Thomas Mailund, Rasmus Nielsen, and three anonymous reviewers on earlier versions of this manuscript greatly improved this work.

Appendix

Using recursion Equation 2 we can write down the GF equations for the continuous analog of the IUA model where the times between population divergence and admixture events (i.e., Tgf, τ1 and τ2, Figure 1A) are exponentially distributed. The terms for the four sample states that arise as a result of the admixture event are

The remaining states and their GF terms are identical to those in the divergence model without admixture (see equation 1 in Lohse et al. 2012, appendix, with β = 1):

Using Mathematica, this set of equations is easily solved. Although the expression is cumbersome (see File S1), decomposing it into the contributions from the three different topologies (Lohse et al. 2011) yields relatively compact formulae:

| (A1) |

The above uses the fact that the GF for each topology depends only on the intervals between the two coalescence events with corresponding dummy variables ω3 and ω2. Note also that τ1 and τ2 are the times between admixture and divergence events (Figure 1A). The corresponding times from the present are T1 = Tgf + τ1 and T2 = Tgf + τ1 + τ2.

Without admixture (i.e., f → 0 and Tgf → 0) Equation A1 above reduces to equations 3 and 4 in Lohse et al. (2012). For simplicity, the model described above assumes that both ancestral populations are of the same size. To relax this assumption we define a rate α of pairwise coalescence in the population ancestral to A and B (the IUA2 model, see File S1), giving

| (A2) |

Using Equation 2, the GF for a model of AS can be derived analogously (see File S1).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: R. Nielsen

Literature Cited

- Briggs A. W., Stenzel U., Johnson P. L. F., Green R. E., Kelso J., et al. , 2007. Patterns of damage in genomic DNA sequences from a Neandertal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104(37): 14616–14621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui R., Schumer M., Kruesi K., Walter R., Andolfatto P., et al. , 2013. Phylogenomics reveals extensive reticulate evolution in Xiphophorus fishes. Evolution 67(8): 2166–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand E. Y., Patterson N., Reich D., and M. Slatkin, 2011. Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28(8): 2239–2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton D. A. R., Ree R. H., 2013. Inferring phylogeny and introgression using RADseq data: an example from flowering plants (Pedicularis: Orobanchaceae). Syst. Biol. 62: 689–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A. W. F., 1972. Likelihood. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A., and A. Manica, 2012 Effect of ancient population structure on the degree of polymorphism shared between modern human populations and ancient hominins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109: 13956–13960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J., 1988. Phylogenies from molecular sequences: inference and reliability. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22: 521–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz L., Schraiber J. G., Madsen O., Megens H. J., M. Bosse et al, 2013. Genome sequencing reveals fine scale diversification and reticulation history during speciation. Genome Biol. 14: R107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R. E., Krause J., Briggs A. W., Maricic T., Stenzel U., et al. , 2010. A draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome. Science 328(5979): 710–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heliconius Genome Consortium , 2012. Butterfly genome reveals promiscuous exchange of mimicry adaptations among species. Nature 487: 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R. R., 2002. Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics 18: 337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R. R., Kaplan N. L., 1985. Statistical properties of the number of recombination events in the history of a sample of DNA sequences. Genetics 111: 147–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulathinal R. J., Stevison L. S., Noor M. A. F., 2009. The genomics of speciation in Drosophila: diversity, divergence, and introgression estimated using low-coverage genome sequencing. PLoS Genet. 5(7): e1000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawniczak M. K. N., Emrich S. J., Holloway A. K., Regier A. P., Olson M., et al. , 2010. Widespread divergence between incipient Anopheles gambiae species revealed by whole genome sequences. Science 330(6003): 512–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R., 2011. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature 475(7357): 493–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse, K., 2010 Inferring population history from genealogies. Ph.D. Thesis, Edinburgh University, Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Lohse K., Harrison R. J., Barton N. H., 2011. A general method for calculating likelihoods under the coalescent process. Genetics 58: 977–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse K., Barton N. H., Melika N., Stone G. N., 2012. A likelihood-based comparison of population histories in a parasitoid guild. Mol. Ecol. 49(3): 832–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. H., Dasmahapatra K. K., Nadeau N. J., Salazar C., Walters J. R., et al. , 2013. Genome-wide evidence for speciation with gene flow in Heliconius butterflies. Genome Res. 23: 1817–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean G. A., Cardin N. J., 2005. Approximating the coalescent with recombination. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 360(1459): 1387–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R., Wakeley J., 2001. Distinguishing migration from isolation: a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach. Genetics 158: 885–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N., Richter D. J., Gnerre S., Lander E. S., Reich D., 2006. Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees. Nature 441(7097): 1103–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph P., Coop G., 2013. The geography of recent genetic ancestry across Europe. PLoS Biol. 11(5): e1001555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C. R., 1945. Information and the accuracy attainable in the estimation of statistical parameters. Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc. 37: 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sankararaman S., Patterson N., Li H, Pääbo S., Reich D., 2012. The date of interbreeding between neandertals and modern humans. PLoS Genet. 8(10): e1002947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M., Pollack J. L., 2008. Subdivision in an ancestral species creates asymmetry in gene trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25(10): 2241–2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall J. D., 2003. Estimating ancestral population sizes and divergence times. Genetics 163: 395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall J. D., Yang M. A., Jay F., Kim S. K., Durand E. Y., et al. , 2013. Higher levels of Neanderthal ancestry in East Asians than in Europeans. Genetics 194: 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Hey J., 2010. Estimating divergence parameters with small samples from a large number of loci. Genetics 184: 363–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson-Herbots H. M., 2008. The distribution of the coalescence time and the number of pairwise nucleotide differences in the “isolation with migration” model. Theor. Popul. Biol. 73(2): 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram Research, 2010 Mathematica, Version 8.0. Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Yang M. A., Malaspinas A.-S., E. Y. Durand, and M. Slatkin, 2012. Ancient structure in Africa unlikely to explain Neanderthal and non-African genetic similarity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29(10): 2987–2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., 2002. Likelihood and Bayes estimation of ancestral population sizes in hominoids using data from multiple loci. Genetics 162: 1811–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T., Yang Z., 2012. Maximum likelihood implementation if an isolation-with-migration model with three species for testing speciation with gene flow. Mol. Biol. Evol. 49(3): 832–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.