Abstract

In child sexual abuse cases, the victim’s testimony is essential, because the victim and the perpetrator tend to be the only eyewitnesses to the crime. A potentially important component of an abuse report is the child’s subjective reactions to the abuse. Attorneys may ask suggestive questions or avoid questioning children about their reactions, assuming that children, given their immaturity and reluctance, are incapable of articulation. We hypothesized that How questions referencing reactions to abuse (e.g., “how did you feel”) would increase the productivity of children’s descriptions of abuse reactions. Two studies compared the extent to which children provided evaluative content, defined as descriptions of emotional, cognitive, and physical reactions, in response to different question-types, including How questions, Wh-questions, Option-posing questions (yes–no or forced-choice), and Suggestive questions. The first study examined children’s testimony (ages 5–18) in 80 felony child sexual abuse cases. How questions were more productive yet the least prevalent, and Option-posing and Suggestive questions were less productive but the most common. The second study examined interview transcripts of 61 children (ages 6 –12) suspected of being abused, in which children were systematically asked How questions regarding their reactions to abuse, thus controlling for the possibility that in the first study, attorneys selectively asked How questions of more articulate children. Again, How questions were most productive in eliciting evaluative content. The results suggest that interviewers and attorneys interested in eliciting evaluative reactions should ask children “how did you feel?” rather than more direct or suggestive questions.

Keywords: children, child sexual abuse, emotion, question type

The testimony of the alleged child victim is often the most important evidence in the prosecution of child sexual abuse (Myers et al., 1999). The child and the suspect are usually the only potential eyewitnesses (Myers et al., 1989), and physical evidence is often lacking (Heger, Ticson, Velasquez, & Bernier, 2002).

An important aspect of credibility is the extent to which the witness describes his or her reactions to the alleged events. The Story Model of juror decision-making states that jurors are more likely to believe the party that presents a coherent narrative (Pennington & Hastie, 1992). Coherent narratives consist of logically and sequentially connected events and include the “internal response” of the narrator (Stein & Glenn, 1979; see also Labov & Waletsky, 1967). Several researchers have argued that child witnesses’ accounts of their subjective reactions are an important aspect of their abuse narratives (Snow, Powell, & Murfett, 2009; Westcott & Kynan, 2006).

An unanswered question is how allegedly abused children should be questioned about their reactions to abuse. A classic finding in research on questioning adults is that open-ended questions elicit longer responses than closed-ended questions (questions that can be answered with a single word or detail) (Dohrenwend, 1965; Richardson, Dohrenwend, & Klein, 1965). Similarly, research on courtroom questioning has found that open-ended questions are more conducive to the production of a narrative (O’Barr, 1982). However, when specific information is required, particularly information that the respondent may be reticent to report, then closed-ended questions can be more productive (Dohrenwend, 1965; Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948). With respect to children, closed-ended questions are likely to be more successful than open-ended questions in eliciting information that children have difficulty in recalling on their own (Lamb et al., 2008). Furthermore, there is some evidence that when children are reluctant to disclose information, more direct questions may be necessary to elicit true disclosures. For example, studies on children’s disclosure of wrongdoing have found that direct questions are more productive than questions asking for free recall (Bottoms et al., 2002; Pipe & Wilson, 1994). Similarly, studies examining children’s disclosure of genital touch have found that open-ended questions are less likely to elicit true disclosures than closed-ended questions (Saywitz et al., 1991). Similarly, based on the assumption that children require assistance in articulating their reactions to alleged abuse, either because of inhibition or inability, some have recommended a reflection approach in which the adult questioner interprets the child’s actions or statements as evincing a particular reaction and asks the child to agree or disagree (Leventhal, Murphy, & Asnes, 2010).

However, closed-ended questioning of children alleging abuse has been challenged in two ways. First, a large body of research has demonstrated that children’s responses are more likely to be accurate when asked Wh- questions, particularly more open-ended Wh- questions (such as “what happened”), than when asked option-posing questions, which include forced-choice questions and questions that can be answered “yes” or “no.” In short, children’s recall performance is more accurate than their recognition performance (Lamb et al., 2008). More surprisingly, a series of studies by Lamb and colleagues of children questioned about sexual abuse in forensic interviews has shown that open-ended questions, including questions such as “what happened” and Wh-questions about specific aspects of alleged abuse, elicit more details per question than option-posing questions, including yes/no and forced-choice questions (Lamb et al., 2008). This research challenges the view that it is necessary to ask abused children direct questions to elicit complete reports.

Whether children alleging sexual abuse are capable (and willing) of describing their reactions to abuse, and whether their responses are affected by the type of questions they are asked, has received little attention. With only a few exceptions, research on child sexual abuse interviews fails to separately categorize children’s evaluative reactions. Lamb and colleagues (1997) analyzed 98 transcripts of investigative interviews with 4- to 13-year-old children disclosing sexual abuse. Of the 85 that were judged as plausible (based on independent evidence), slightly less than half (49%) contained any report of “subjective feelings” (p. 261). The type of questions that elicited subjective feelings was not analyzed. Westcott and Kynan (2004) examined 70 transcripts of investigative interviews with 4- to 12-year-old children about sexual abuse. The authors found that only 20% of children spontaneously described emotional reactions (5% of children under 7) and only 10% spontaneously described their physical reactions (0% of children under 7). On the other hand, some mention was made of emotional reactions in 66% of the interviews and some mention of physical reactions in 47%. The type of questions that elicited reactions were not analyzed, and precisely what qualified as spontaneous was not clear. In a different study examining the same interviews, the authors noted that interviewers often failed to give children the opportunity to provide spontaneous descriptions (Westcott & Kynan, 2006). Snow, Powell, and Murfett (2009) examined 51 interviews with 3- to 16-year-old children alleging sexual abuse. They found that open-ended questions were no more likely than specific questions to elicit reports of the child’s subjective response to the alleged abuse; among children under 9 years of age, open-ended questions were marginally less likely to elicit such details (p = .055). Open-ended questions were defined as questions that were “designed to elicit an elaborate response without dictating what specific details the child needed to report” whereas all other questions were classified as specific (p. 559). Hence, the possibility that different types of questions about children’s evaluative reactions would vary in productivity was not explored.

All of the research on children’s productivity in response to different question types has examined forensic interviews. Children might be particularly reticent in the courtroom, which is likely to be more stressful and intimidating than pretrial interviews. Indeed, in the United States, evidentiary rules against the use of leading questions by the prosecution are relaxed in the case of child witnesses, because of both potential memory difficulties and reluctance (Mueller & Kirkpatrick, 2009). Lab studies have found that children’s responsiveness declines when they are questioned in a courtroom environment (Hill & Hill, 1987; Saywitz & Nathanson, 1993). Questioning in real-world cases might be yet more stressful than courtroom simulations, because in the real-world children testify about victimization and are forced to confront the accused, usually a familiar adult. Indeed, examining children’s in-court performance on questions about their testimonial competency, Evans and Lyon (2011) found that they performed worse than one would expect based on lab research.

There are a number of reasons why children might not spontaneously produce evaluative reactions to abuse. As already noted, they may be reluctant to do so. In addition, children may need memory cues to remember their reactions. Child abuse interviews are by definition focused on the behavior of the alleged perpetrator, and it may simply not occur to children to report their subjective reactions. On the other hand, it may not be possible to facilitate children’s expression of evaluative information. Given their cognitive immaturity, children may have difficulty in articulating their reactions to abuse. For example, children may have ambivalent reactions but be unable to articulate such reactions because of their limited understanding of ambivalence (Harter & Whitesell, 1989). More controversially, children may not experience strong reactions to abuse. Based on her interviews with adults molested as children, Clancy (2009) has argued that many of the adverse reactions to sexual abuse involve the retrospective assessment of the abuse by the victim years after the abuse occurs. Clancy found that although most understood that the abuse was wrong when it occurred (85%), the most common reaction was confusion (92%).

Present Research

Based on research suggesting that most abused children do not spontaneously produce evaluative information about abuse, we tentatively hypothesized that children are unlikely to spontaneously describe reactions when asked questions about alleged abuse, but that they are capable of generating information when asked questions that refer specifically to their reactions. However, given the lower productivity of option-posing questions in field studies of child abuse interviews, we predicted that children would be more inclined to provide evaluative content when asked questions that specifically referred to evaluation through How questions and Wh- questions rather than option-posing questions. The first study analyzed transcripts of children testifying in felony child sexual abuse trials. The second study examined forensic interviews of sexually abused children who were systematically asked How questions about their reactions to alleged abuse.

Study 1

Method

Pursuant to the California Public Records Act (California Government Code 6250, 2010), we obtained information on all felony sexual abuse charges under Section 288 of the California Penal code (contact sexual abuse of a child under 14 years of age) filed in Los Angeles County from January 2, 1997 to November 20, 2001 (n = 3,622). Sixty-three percent of these cases resulted in a plea bargain (n = 2,275), 23% were dismissed (n = 833), and 9% went to trial (n = 309). For the remaining 5% of cases, the ultimate disposition could not be determined because of missing data in the case tracking database. Among the 309 cases that went to trial, 82% led to a conviction (n = 253), 17% an acquittal (n = 51), and the remaining five cases were mistrials (which were ultimately plea-bargained).

For all convictions that are appealed, court reporters prepare a trial transcript for the appeals court. Because criminal trial transcripts are public records (Estate of Hearst v. Leland Lubinski, 1977), we received permission from the Second District of the California Court of Appeals to access their transcripts of appealed convictions. We paid court reporters to obtain transcripts of acquittals and nonappealed convictions. We were able to obtain trial transcripts for 235 of the 309 cases, which included virtually all of the acquittals and mistrials (95% or 53/56) and 71% (182/253) of the convictions. Two hundred eighteen (93%) of the transcripts included one or more child witness under the age of 18 at the time of their testimony. These transcripts included a total of 420 child witnesses, ranging in age from 4 to 18 years of age (M = 12, SD = 3, 82% female), with only 5% of children at trial 6 years or younger.

We randomly selected 80 child witnesses testifying at trial. Transcripts were eligible to be selected if the testimony was in English and if the child was testifying as a victim. This yielded a sample of children ranging in age from 5–18 years old, with a mean of 12 years old (SD = 3; 85% female). The mean delay between indictment and testimony was 284 days (SD = 145). Sixty-six percent (n = 53) of the cases were convictions, 26% (n = 20) were acquittals, and 8% (n = 7) mistrials. Half the cases involved allegations of interfamilial sexual abuse, and half the cases involved genital or anal penetration. All questions and answers were coded for their content for a combined total n = 16,495 of question/answer turns. Two assistants coded the transcripts. To test interrater reliability, both coders evaluated 15% of the data set at the beginning, middle, and end of the coding process. The mean Kappa overall was .96, with a range of .91–1.0.

One variable was question type. Questions were classified into one of four categories, based on a modified version of the typology used by Lamb and colleagues (2003). Option-posing questions included yes–no questions and forced-choice questions. Yes–no questions are questions that can be answered “yes” or “no” (e.g., “did it hurt?”), and forced-choice questions use “or” and provide response options (e.g., “did it feel good or bad?”). Wh- questions are questions prefaced with “who,” “what,” “where,” “when,” or “why” (e.g., “where did it hurt?”). How questions are questions prefaced with “how” (e.g., “how did it feel?”). Suggestive questions include tag questions and negative term questions. Tag questions are yes–no questions that contain a statement conjoined with a tag such as “isn’t that so?” (e.g., “he hurt you, didn’t he?”) and negative term questions are yes–no questions that embed the tag into the question (e.g., “didn’t he hurt you?”). Of all questions posed, 63% were Option-posing questions (n = 10,358), 25% were Wh- questions (n = 4,150), 6% were How questions (n = 1,010), and 6% were Suggestive questions (n = 977). Whereas prosecutors asked the majority of Option-posing (60%, n = 6,204), Wh- (77%, n = 3,193), and How questions (66%, n = 662), 79% (n = 772) of the Suggestive questions were asked by defense attorneys.

Another variable was evaluative content. We classified questions and answers as containing evaluative content if they contained references to emotional, cognitive, or physical reactions. When possible, evaluative references were specifically identified. Emotional content included any emotional label or emotion-signaling action (e.g., “I hated him”; “I was crying”). Cognitive content included any reference to the speaker’s cognitive processes at the time of the event, such as intent, desire, hope, hypothesis, or prediction (e.g., “what did you think?”; “were you confused?”). This did not include references to the speaker’s cognitive state at the time of the testimony (e.g., “I think it was a Tuesday”). Physical content included reference to any physical sensation (e.g., “did it hurt?”). Questions that contained evaluative content but that did not refer specifically to a type of reaction were coded as generic (e.g., “how did you feel,” which can refer to emotional, physical, or cognitive reactions).

Results

Preliminary analyses found that gender and delay from indictment to trial did not affect the results, and these factors are not considered further. We first examined whether question type and the presence of evaluative content in the questions affected children’s production of evaluative content. This analysis included all question/answer turns (n = 16,495). The range of question/answer turns per child was 12 through 1,666 with a mean of 210 (SD = 240) and median of 142. A majority of child witnesses (93%; n = 74) received at least one question with evaluative content, and most (74%; n = 59) children gave at least one answer with evaluative content. Only 6% (n = 1,032) of all questions asked contained evaluative content. Across the four question types (Option-posing, Wh-, How, and Suggestive), 5% to 11% of the questions contained evaluative content. When the question contained evaluative content, children responded with evaluative content 23% of the time (n = 232). When the question did not include evaluative content, children produced evaluative content approximately 2% of the time (n = 342).

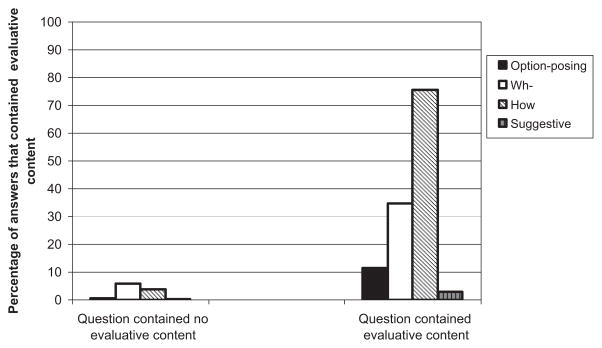

The likelihood that questions with and without evaluative content elicited evaluative answers, subdivided by question type, is shown in Figure 1. How questions with evaluative content were most likely to lead to answers with evaluative content. We conducted a nested logistic regression in which the dependent variable was whether or not the response contained evaluative content. Dummy codes1 for each subject were entered into the model on the first block, and then the other predictors (i.e., age, question content, and question type) were entered on the second block. This approach allows one to determine the increase in the model fit over and above simply knowing the identity of the child. We included an interaction term for question type and question content to assess our hypothesis that questions would be particularly productive if they included evaluative content and were Wh- or How questions. The first block was significant χ2 (79, n = 16,495) = 316.98, p <.001, reflecting differences across children in their responses. The second block, measuring the additional influence of age and question-type, was also significant, χ2 (8, n = 16,495) = 1115.83, p < .001. For every year increase in age, the odds of the response containing evaluative content increased by about 29, 95% confidence interval (CI) [22.0, 43.5] (B = 3.4, Wald = 6.04, p < .01). Including evaluative content in the question increased the odds of an evaluative response by 18, 95% CI [12.5, 24.7] (B = 2.9, Wald = 6.7, p < .001). Compared with Option-posing questions, Wh- questions increased the odds of the response containing an evaluative reference by 9, 95% CI [6.6, 11.4] (B = 2.2, Wald = 243, p < .001), How questions increased the odds by 5, 95% CI [3.4, 8.0] (B = 1.7, Wald = 243, p < .001), and Suggestive questions nonsignificantly decreased the odds of an evaluative reference by 3, 95% CI [1, 6.7] (B = −1.24, Wald = 2.97, p = .085). However, the interaction between evaluative content and question type was also significant, Wald = 45.18, p < .001, reflecting the importance of considering the joint effects of evaluative content in the question and question type. As Figure 1 shows, although Wh- questions outperform How questions when there is no evaluative content in the question, the most productive questions overall are How questions with evaluative content. Among questions without evaluative content, Suggestive questions compared to option-posing questions nonsignificantly decrease the likelihood of an evaluative response by 3, 95% CI [1.0, 6.4] (B = −1.31, Wald = 3.3, p = .069); Wh- questions increase the odds by 9, 95% CI [6.6, 11.4] (B = 2.16, Wald = 239.38, p < .001), and How questions increase the odds by 5, 95% CI [3.4, 8.1] (B = 1.66, Wald = 58.33, p < .001). Among questions with evaluative content, Suggestive questions nonsignificantly decrease the odds of an evaluative response by 3, 95% CI [1.0, 8.1] (B = −1.22, Wald = 2.60, p = .11), Wh- questions increase the odds by 5, 95% CI [3.0, 7.2] (B = 1.53, Wald = 46.32, p < .001), and How questions increase the odds by 31, 95% CI [16.6, 57.3] (B = 3.43, Wald = 119, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Percentage of answers in Study 1 that contained evaluative content subdivided by whether the question contained evaluative content and by question type.

Because How questions with evaluative content were most productive, we then focused on these questions in the second analysis (n = 103). This yielded a sample of 45 subjects. Each child received from one to six How questions with evaluative content (M = 2.36, SD = 1.4, Median = 2). The “how did you feel” questions (n = 73) were coded as generic (because they do not specifically request emotional, cognitive, or physical information), whereas questions that did request such information were coded as specific (n = 30). Ninety-two percent (n = 67) of the generic questions elicited evaluative content, whereas 30% (n = 9) of the specific questions did so. We conducted a nested logistic regression with evaluative content as the dependent variable, child entered on the first block, and age and question specificity (generic vs. specific) entered on the second block. The first block was significant, χ2 (44, n = 103) = 78.78, p < .001, as was the second block, χ2 (2, n = 103) = 12.68, p < .001. Whereas age was not significantly related to evaluative content, question specificity was, and generic questions increased the odds of an evaluative response by 26, 95% CI [8.1, 37.2] (B = 3.28, Wald = 29.05, p < .001.).

Discussion

When answering questions about sexual abuse, children rarely spontaneously provided evaluative information. However, this could not be attributed to memory failure, inarticulability, or a lack of evaluative reactions, because children were quite likely to produce evaluative content if the question referenced such content and was phrased as a How question. Attorneys primarily asked Option-posing questions and only rarely asked How questions, and this appeared to suppress children’s production of evaluative information. The most productive type of How questions were those that referred generically to evaluation—“how did you feel”—rather than specific inquiries into the child’s emotional, physical, or cognitive reactions. The results suggest that to elicit evaluative information from child witnesses about abuse, it is necessary to be more direct than the most open-ended questions about abuse but less leading than option-posing or suggestive questions.

This study provided the first opportunity to assess the productivity of children testifying in court. Given the stressfulness of courtroom testimony, it is important to determine whether the relation between question type and productivity in interviews in the field replicate in the courtroom. Moreover, this is the first study to look closely at the relation between question-type and children’s production of evaluative information. The level of specificity required to elicit such information has been obscured by a failure to draw fine distinctions among different types of questions.

One limitation is that the child witnesses were not systematically asked the same sorts of questions about their reactions to alleged abuse. Gilstrap and colleagues (Gilstrap & Ceci, 2005; Gilstrap & Papierno, 2004) have demonstrated that children’s responses affect the suggestiveness of interviewers’ questions. Rather than reflecting productivity differences in question-type, the results could be the product of attorneys framing questions in response to differences in children’s productivity. If attorneys were more inclined to ask “how did you feel” questions of loquacious children, then the relation between question-type and productivity could be spurious. Moreover, attorneys might have selectively asked evaluative questions of children who had been forthcoming about their reactions in pretrial interviews. Hence, an important step is to examine the effect of “how did you feel” questions when asked in a systematic fashion. In Study 2 we examined children’s responses to different type of questions in forensic interviews in which “how did you feel” questions were scripted. Although the interviews were conducted in a less stressful context than the testimony in Study 1, the fact that the questions were scripted allowed us to ensure that the productivity differences in Study 1 were not attributable to attorneys’ choices of which questions to ask.

Study 2

Method

The current sample comprised transcripts from forensic interviews that took place at the Los Angeles County–USC Violence Intervention Program (VIP). Children are referred to the center by children protective services and/or the police based on suspicions of child abuse. Upon arrival all children were first given a medical examination for possible physical evidence of sexual abuse and were subsequently interviewed by one of six interviewers. Children were eligible for the study if they were between 6 and 12 years of age, their interview was recorded successfully, and they disclosed sexual abuse during the interview. This yielded a sample of 61 children (M = 9 years, SD = 2). The majority of subjects (80%; n = 49) were female. The interviewers were trained by the first author to follow an interview protocol. The first phase of the interview consisted of instructions, which were designed to increase the child’s understanding of the requirements of an interview. They included instructions on the importance of telling the truth, the acceptability of “I don’t know,” “I don’t understand,” and “I don’t want to talk about it” responses, and the appropriateness of correcting the interviewer’s mistakes. The second phase of the interview consisted of two practice narratives. The purpose of this part of the interview was to teach the child to provide elaborated narrative responses. The practice narratives also allow the child and the interviewer to relax and to build rapport. The interviewer first said to the child, “First I’d like you to tell me something about your friends and things you like to do and things you don’t like to do.” The interviewer followed up with prompts that repeated the child’s information and asked the child to “tell me more,” as well as questions such as “What do you and your friends do for fun?” The second practice narrative asked the child to narrate events in time. The interviewer said, “Now tell me about what you do during the day. Tell me what you do from the time you get up in the morning to the time you go to bed at night.” The interviewer followed up with prompts that repeated the child’s information and asked the child to tell “what happens next.”

In the third phase of the interview the interviewer asked the child to draw a picture of his or her family, and to “include whoever you think is a part of your family.” The interviewer asked the child to identify the various people he or she drew.

The fourth phase of the interview consisted of the “feelings task,” in which the interviewer asked the child to “tell me about the time” he or she was “the most happy,” “the most sad,” “the most mad,” and “the most scared.” The interviewer followed up the child’s responses with “tell me more” prompts.

The fifth phase of the interview consisted of the “allegation phase.” This phase was designed to elicit disclosures of abuse among children who had not already mentioned the topic during the earlier phases of the interview. A third of the children disclosing abuse (33%, n = 20) did so before the allegation phase. 15% (n = 9) did so in response to the “feelings task.” Interviewers asked a scripted set of questions that began with an open-ended invitation to “tell me why you came to talk to me” and that became more focused if the child failed to mention abuse. If the child did mention abuse, the interviewer repeated the child’s statement and then asked “Tell me everything that happened, from the very beginning to the very end.” As follow-up questions, in addition to eliciting additional details about the alleged abuse, interviewers were specifically instructed to ask children “how did you feel when [abuse occurred],” and “how did you feel after [abuse occurred].”

Questions were classified in a manner consistent with the procedure described in Study 1. Limiting analyses to the substantive questions about alleged abuse, there were 3,582 total questions of which 59% were Option-posing (n = 2,128), 32% were Wh- (n = 1,155), 8% were How questions (n = 292), and .2% were Suggestive (n = 7). Because so few questions were Suggestive, we recategorized them as Option-posing in subsequent analyses.

Results

The range of question/answer turns per child was six through 127 with a mean of 59 (SD = 27, median = 54). All subjects received at least one question with evaluative content, and almost all (93%; n = 57) subjects gave at least one response with evaluative content. Of all questions asked, 9% (n = 312) contained evaluative content. Whereas 55% of the How questions contained evaluative content, 5% of Option-posing questions and 4% of Wh- questions did so. Overall, when the question contained evaluative content, children generated content 59% of the time (n = 183). When the question did not refer to evaluative content, subjects generated evaluative content 6% of the time (n = 228).

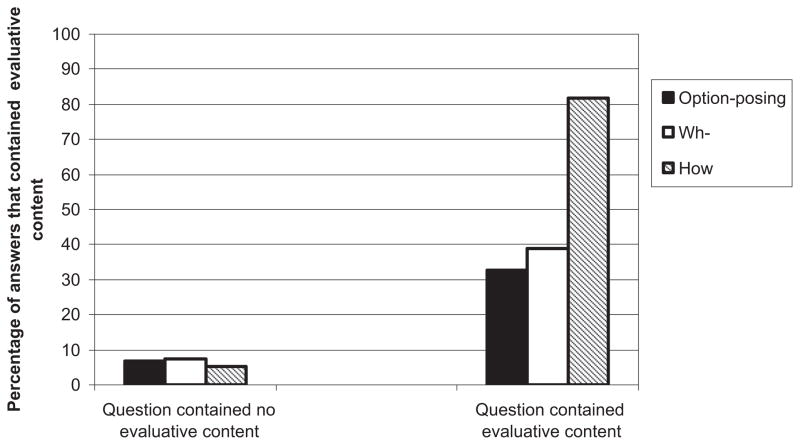

The likelihood that questions with and without evaluative content elicited evaluative answers, subdivided by question type, is shown in Figure 2. How questions with evaluative content were the most productive. As in Study 1, we conducted a nested logistic regression predicting evaluative content in the answer, in which a dummy code for each child was entered in the first block, and age, evaluative content in the question, and question-type were entered in the second block. The first block was significant, χ2 (60, n = 3,582) = 175.82, p < .001, as was the second, χ2 (6, n = 3,582) = 557.95, p < .001. For every year increase in age, the odds of the response containing evaluative content increased by 1.14, 95% CI [1.0, 1.2] (B = .129, Wald = 19.6, p < .001). Compared to questions without evaluative content, questions that contained evaluation increased the odds of an evaluative response by 8, 95% CI [4.6, 12.7] (B = 2.1, Wald = 64.8, p < .001). Question-type was not significant, Wald = 2.8, p < .24. However, the interaction between evaluative content in the question and question-type was significant, Wald = 28.7, p < .001, reflecting the fact that the relation between evaluative content in the question and in the answer depended on question-type. Among questions without evaluative content, question-type did not affect the likelihood that the child produced evaluative content (both ps > .10) Among questions with evaluative content, Wh- questions did not affect the likelihood of an evaluative response compared to option-posing questions ( p > .10), whereas How questions increased the odds by 15, 95% CI [8.0, 40.0] (B = 2.73, Wald = 26.69 p < .001).

Figure 2.

Percentage of answers in Study 2 that contained evaluative content subdivided by whether the question contained evaluative content and by question type.

As in Study 1, the second analysis determined what type of How questions with evaluative content were most productive. The dataset was truncated to include cases in which a How question contained evaluative content (n = 159). Questions were again coded as generic or specific. Generic questions included “how did you feel” (n = 95), whereas specific questions referred to emotional, cognitive, or physical content (n = 64). One hundred percent (n = 95) of the generic questions elicited evaluative content, whereas 55% (n = 35) of the specific questions did so. Because all of the generic questions elicited evaluative content, we were unable to conduct a logistic regression on the data, but Fisher’s exact test confirmed that the difference between the productivity of generic and specific How questions was statistically significant, p < .001.

Discussion

The results were largely consistent with Study 1. Children rarely mentioned their evaluative reactions spontaneously, as questions without evaluative content almost never elicited evaluative responses. How questions with evaluative content were quite likely to elicit evaluative information, and the most productive questions were “How did you feel” questions, which were 100% effective. Interviewers were specifically trained to systematically inquire into children’s reactions to the alleged abuse, including “how did you feel” questions. Hence, these results are not subject to the possibility in Study 1 that certain types of evaluative questions were only asked of more loquacious children.

Unlike Study 1, when the questions contained evaluative content, Wh- questions were not more productive than Option-posing questions. Comparing Figures 1 and 2, this appears to be attributable to the fact that whereas option-posing questions virtually never produced evaluative content in Study 1, they did so about one third of the time in Study 2. The reasons for this difference are unclear, and any comparison between studies must be made with caution. Tentatively, we suspect that children cued with evaluative content in a forensic interview may be more likely to generate evaluative information than when questioned in court, because of the stressfulness of testifying in court.

A unique aspect of the interviews in Study 2 was that interviewers asked children to describe events that had made them happy, sad, mad, and scared as part of the rapport building. Notably, 15% of the children disclosed abuse at this point in the interview. This suggests that although children do not spontaneously report evaluative reactions to abuse, evaluative reactions may serve as a cue for abuse disclosure.

General Discussion

In both court and in forensic interviews, children provided few evaluative details when questioned about alleged abuse but were quite capable of doing so if asked evaluative questions such as “how did you feel?” Although older children were more articulate than younger children, children of all ages were more likely to produce evaluative details when the question referred to evaluation and when the questioner avoided asking Option-posing or Suggestive questions. The results suggest that children disclosing abuse are capable of describing their reactions (and do in fact have reactions) but that their tendency to do so depends on the content and form of the questions they are asked.

One implication of the findings is that asking children about their evaluative reactions may enable abused children to provide more credible reports. When children’s reports fail to mention their reactions, this may increase skepticism among those who evaluate the truthfulness of abuse reports. Evaluative reactions are an important component of well-formed narratives (Labov & Waletsky, 1967; Stein & Glenn, 1979), and well-formed narratives are likely to be more convincing (O’Barr, 1982; Pennington & Hastie, 1992). Although we are not aware of any research specifically examining the effects of child witnesses’ production of evaluative reactions on jurors, Connolly and colleagues (2009, 2010) found that judges frequently mentioned alleged victims’ conduct at the time of abuse in justifying their decisions (and conduct included emotional reactions).

Examination of the transcripts of the forensic interviews revealed a rich variety of descriptions. In response to the contemporaneous feelings question (“how did you feel when [abuse occurred]”), some children described physical reactions. One 12-year-old child explained “I felt bad. Like I felt like like he was entering me, it hurt me, my stomach hurts, all of my hurt, my legs hurt.” An 11-year-old responded “It was thick and it hurt.” The interviewer repeated the child’s words (“it was thick and it hurt,”) and the child continued “And he was more heavy,” suggesting the sensation of an 11-year-old girl under an adult male—who could easily weigh twice as much as she. A 7-year-old boy simply responded, “I was gonna puke.” Other children referred to emotional reactions, including fear (“scared”), disgust (“grossed out”), and anger (“mad”).

Children also brought up other aspects of the alleged abuse, such as threats and subsequent events. For example, “Scared ’cause he told me not to tell anybody and I didn’t know what was gonna happen if I told somebody” (10-year-old). Another child described her surprise, and then returned to her narrative of what occurred:

I think “what is he doing?” and then and then I said “stop” and he was run and and then he start putting his hand under my shirt and I said “stop” and then my grandma come (9-year-old).

Children’s answers to the questions about subsequent feelings also included both references to physical feelings and to emotions. Here, too, some children described pain: “A: I like hurt. Q: Where did you hurt? A: Like in my private area and I had a real bad headache” (12-year-old). As before, some children described fear, and their fear after the abuse could explain a failure to disclose the abuse: “I got scared and I just didn’t, I just wanted my mother to pick me up the next day I didn’t say anything” (10-year-old). Children also described depression (“sad”) and guilt (“I feel feel dirty and I felt terrible”). Some children differentiated between how they felt during alleged abuse and how they felt afterward: “Q: You felt grossed out? How did you feel after? A: Sad.” (10-year-old); “Q: Disgusted. What did you feel after? A: I felt like we were doing something wrong.” (11-year-old). In three cases, children described negative reactions at the time of the abuse, but indicated that these feelings had abated afterward (“I was only thinking,” “Safe,” and “Fine”).

Perhaps the most articulate child we spoke to was a 10-year-old child. She described abuse by her stepfather lasting several years, including fondling, digital penetration, and penile penetration of the vagina and anus. The girl first disclosed on a night her younger brother disclosed to her mother that he had been sodomized by an uncle (the step-father’s brother). The mother asked the girl if anything like that had ever happened to her and she said “no.” The mother then told her that she loved her and that she could tell her anything. The girl began to cry, and disclosed the abuse. She explained later that when she saw that her mother was not angry at her brother for disclosing abuse, she felt able to reveal it herself.

A few days after she disclosed to her mother, the girl was interviewed by a district attorney and a police officer. The records lacked any discussion of her reactions to the alleged abuse. The D.A. declined to file charges, citing her inconsistencies regarding what acts had occurred at which location, the lack of physical evidence of abuse, and her motive to lie about her stepfather because of her interest in reconnecting with her biological father. According to the police reports, the step-father fled and was believed to have moved to Mexico.

In our interview, the child disclosed abuse in response to the question “tell me about the time you were the most sad.” Prior to the “how did you feel questions,” she had mentioned that the abuse was unwanted (“I didn’t want him to do that”; “I always sometimes wanted to scream but I didn’t scream”) but had not described other reactions.

Q: How did you feel when he touched you?

A: Kind of angry at him cause he shouldn’t be doing that and sometimes I thought that he was doing that ’cause I wasn’t his daughter (oh, o.k.) I felt kind of mad, disappointed. ’Cause in front of my mom he always say that he love me really. And on my mind I say that if he loves me why was he doing that to me.

Q: Okay. How did you feel after he touched you?

A: I felt like nasty. Like dirty.

Q: Really. Tell me about that, dirty and nasty.

A: ’Cause he touch, if he touches me, he touch me, right. Then he just leaves and like if like if I didn’t work anymore just leave me like that (uh-huh). And I felt like mad and at the same time felt kind of dirty because he shouldn’t be doing that because I’m just a little girl.

Children’s ability to describe their reactions to abuse may enhance their credibility. Children typically exhibit little affect when disclosing alleged abuse in forensic interviews (Sayfran, Mitchell, Goodman, Eisen & Qin, 2008; Wood, Orsak, Murphy & Cross, 1996) or when testifying (Goodman et al., 1992; Gray, 1993). Goodman and colleagues (1992) observed 17 children testifying about sexual abuse and found that “[o]verall, the children’s mood was judged to be midway between ‘calm’ and ‘some distress.’” Gray (1993) observed 70 child sexual abuse witnesses and found that more than 80% failed to cry during their testimony, and children’s affect tended to be “normal” or “flat.” Even when children do exhibit negative emotions during testifying, those emotions might be attributable to the anxiety caused by the courtroom context, including the presence of numerous people, questioning by unfamiliar (and sometimes hostile) adults, and separation from caretakers. Indeed, the research on children in court found very little difference in children’s emotional expressiveness when answering abuse versus nonabuse questions (Gray, 1993).

It is possible that by asking children to describe their reactions to abuse, their ability to do so could counteract the negative effects of flattened affect on jurors’ credibility judgments. Jurors expect children to become emotional when disclosing abuse. Regan and Baker (1998) presented mock jurors with descriptions of child witnesses testifying in child sexual abuse cases and found that jurors found child witnesses who cried more credible, accurate, honest, and reliable than children who remained calm, and that jurors were more likely to vote to convict when the child witness cried (see also Golding, Fryman, Marsil & Yozwiak, 2003, who found that crying evoked more belief than either a calm or “hysterical” demeanor). Myers et al. (1999) surveyed actual jurors who had heard children testifying in 42 sexual abuse trials in two states, and similarly found that “[e]motions or emotional behaviors such as crying, fear, and embarrassment were important to jurors” (p. 406). Indeed, the Supreme Court has endorsed the view that jurors’ observation of child victims’ demeanor when testifying is an important aspect of fact-finding (Coy v. Iowa, 1988).

It is also possible that children’s reports of their evaluative reactions are more convincing when they generate their own descriptions (as in response to “how did you feel” questions) rather than simply acquiesce to the questioner’s suggestions (as in response to option-posing or suggestive questions). Mock jurors exhibit some sensitivity to the extent to which children’s reports are spontaneously generated as opposed to the product of suggestive questioning (Buck, Warren, & Brigham, 2004), although their tendency to do so is somewhat fragile (Buck, London, & Wright, 2011; Laimon & Poole, 2008).

On the other hand, it is also possible that reporting of evaluative reactions may sometimes reduce children’s credibility. Reporting of evaluative reactions may backfire if the child’s expressed affect does not match his or her description of his reactions. Furthermore, jurors may expect children to describe certain types of reactions, and a child’s failure to do so may be perceived negatively. For example, there is evidence that jurors expect sexual abuse victims to resist (Broussard & Wagner, 1988; Collings & Payne, 1991), and this may lead jurors to expect children to describe abuse as painful or frightening. Children who fail to describe strong negative reactions may be disbelieved, despite the fact that children often state that they were initially confused by the perpetrator’s actions or did not recognize that the actions were wrong (Berliner & Conte, 1990; Sas & Cunningham, 1995). Because children’s reactions to abuse are varied, some have even argued that questions about children’s reactions to alleged abuse should be presumptively inadmissible at trial (Connolly, Price, & Gordon, 2009). These are important questions for future research. How do jurors weigh expressed and remembered affect? Which children are jurors more inclined to believe: children who are not asked about their reactions or children who describe reactions that fail to match jurors stereotypes? If asking children about evaluative reactions does indeed have negative effects, then an alternative approach is to educate jurors regarding appropriate reactions to abuse through expert testimony (Kovera, Gresham, Borgida, Gray, & Regan, 1997).

A related issue concerns whether reports of evaluative reactions are valid indicia of accuracy, and whether their validity is related to the way in which the evaluative reactions are elicited. Vrij (2005) reviewed the research on Criteria Based Content Assessment, an approach for assessing the truthfulness of witnesses’ reports that includes “subjective reactions” as a factor that is expected to help distinguish between true and false reports. Of the four studies that examined children’s reports, three failed to find that reports of subjective reactions differentiated between true and false reports. For example, Lamb and colleagues (1997) (discussed in the introduction) found that children described subjective reactions in 49% of the cases that independent evidence suggested were true, and in 38% of the cases that were judged to be false, a nonsignificant difference. Future work should consider not just the presence or absence of subjective reactions but the extent to which the child describes those reactions and the types of questions that elicit the report. It is possible that questions such as “how did you feel” might have differential effects on the percentage of true and false reports that contain evaluative information. If these questions are more productive with true cases than with false cases, then they would enhance assessment of child witness accuracy.

As in all field studies, we cannot say with complete confidence that the sexual abuse reports in our studies were true. In both studies it is possible that children’s evaluative statements were the product of prior suggestions or confabulation. However, in Study 1 the evidence was sufficiently strong for the police to refer the case for prosecution and for the prosecutor to take the case to trial. Furthermore, we reran our analyses on the cases that resulted in convictions and obtained the same results. In Study 2 the cases were referred for medical evaluation because of strong suspicions of abuse following child protective services and/or police investigation. Moreover, it is significant that the most productive questions were not the most suggestive or leading. Nevertheless, future laboratory work could incorporate “how did you feel” questions in examining the differences between children’s reports of actually experienced and merely suggested events.

Future research can also explore in greater detail the types of reactions that children describe and whether there are other types of questions that also generate good amounts of evaluative content. For example, we suspect that when children provide physical reactions to the “how did you feel” question, interviewers can profitably follow-up with a “what did you think” question to elicit emotional reactions. Conversely, when children provide emotional reactions to “how did you feel” questions, we would predict that interviewers could elicit physical reactions by following up with “how did your body feel?” Moreover, it would be helpful to systematically explore the extent to which children can elaborate on brief responses to the “how did you feel” questions. Although the question cannot be answered simply “yes” or “no,” and does not provide explicit options (which would enable the child to merely pick one of the options), it is possible to answer the question with a single word (e.g., “sad”). Encouraging children to elaborate on their one-word responses (e.g., “Tell me about that, sad”) might be an effective means of eliciting greater detail.

In sum, the results have clear implications for legal practice. Children can be surprisingly articulate about their reactions to sexual abuse, despite their apparent lack of affect in describing the abuse itself. Investigators and attorneys can profitably ask children more questions about their responses to sexual abuse. Whereas open-ended questions about the abuse event are unlikely to elicit evaluative reactions, specific but nonleading questions can be highly productive.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vera Chelyapov for her assistance in preparing the manuscript and Richard Wiener for his comments on the research. Preparation of this paper was supported in part by National Institute of Child and Human Development Grant HD047290 and National Science Foundation Grant 0241558.

Footnotes

Because each subject was asked multiple questions, the question answer/turns in the current study did not satisfy the assumption of independence (Homer & Lemeshow, 2000). A lack of independence can spuriously influence the parameter estimates by ignoring within-subject variability. One way to control for such dependencies is to create a “dummy code” for each subject (technically for n − 1 subjects; see Bonney, 1987). A dummy code simply indicates what responses came from which subject and allows each subject to be included as a predictor in the model. This approach allows the unique contribution from each subject to be isolated, and it leaves the unit of analysis at the question level while controlling for subject main effects (Collett, 1991).

References

- Berliner L, Conte J. The process of victimization: The victims’ perspective. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1990;14:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonney GE. Logistic regression for dependent binary observations. Biometrics. 1987;43:951–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms BL, Goodman GS, Schwartz-Kenney BM, Thomas SN. Understanding children’s use of secrecy in the context of eyewitness reports. Law & Human Behavior. 2002;26:285–313. doi: 10.1023/A:1015324304975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard SD, Wagner WG. Child sexual abuse: Who is to blame? Child Abuse & Neglect. 1988;12:563–569. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck J, London K, Wright D. Expert testimony regarding child witnesses: Does it sensitize jurors to forensic interview quality? Law and Human Behavior. 2011;35:152–164. doi: 10.1007/s10979-010-9228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck J, Warren AR, Brigham JC. When does quality count?: Perceptions of hearsay testimony about child sexual abuse interviews. Law and Human Behavior. 2004;28:599–621. doi: 10.1007/s10979-004-0486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy SA. The trauma myth: The truth about the sexual abuse of children—And its aftermath. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collett D. Modeling Binary Data. Boca Raton, Fl: Chapman & Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Collings SJ, Payne MF. Attribution of causal and moral responsibility to victims of father-daughter incest: An exploratory examination of five factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1991;15:513–521. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90035-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly DA, Price HL, Gordon HM. Judging the credibility of historic child sexual abuse complaints: How judges describe their decisions. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2009;15:102–123. doi: 10.1037/a0015339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly DA, Price HL, Gordon HM. Judicial decision making in timely and delayed prosecutions of child sexual abuse in Canada: A study of honesty and cognitive ability in assessments of credibility. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2010;16:177–199. doi: 10.1037/a0019050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coy v. Iowa. (1988). 487 U.S. 1012.

- Dohrenwend BS. Some effects of open and closed questions on respondents’ answers. Human Organization. 1965;24:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Estate of Hearst v. Leland Lubinski. (1977). 67 Cal. App. 3d 777.

- Evans AD, Lyon TD. Assessing children’s competency to take the oath in court: The influence of question type on children’s accuracy. Law & Human Behavior. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10979-011-9280-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilstrap LL, Ceci SJ. Reconceptualizing children’s suggestibility: Bidirectional and temporal properties. Child Development. 2005;76:40–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilstrap LL, Papierno PB. Is the cart pushing the horse? The effects of child characteristics on children’s and adults’ interview behaviors. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2004;18:1059–1078. doi: 10.1002/acp.1072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM, Fryman HM, Marsil DF, Yozwiak JA. Big girls don’t cry: The effect of child witness demeanor on juror decisions in a child sexual abuse trial. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:1311–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman GS, Taub EP, Jones DP, England P. Testifying in criminal court: Emotional effects on child sexual assault victims. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57:1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray E. Unequal justice: The prosecution of child sexual abuse. New York, NY: Free Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Whitesell NR. Developmental changes in children’s understanding of single, multiple, and blended emotion concepts. In: Saarni C, Harris PL, editors. Children’s understanding of emotion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 81–116. [Google Scholar]

- Heger A, Ticson L, Velasquez O, Bernier R. Children referred for possible sexual abuse: Medical findings in 2384 children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:645–659. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PE, Hill SM. Videotaping children’s testimony: An empirical view. Michigan Law Review. 1986–1987;85:809–833. [Google Scholar]

- Homer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2. New York, NY: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovera M, Gresham A, Borgida E, Gray E, Regan P. Does expert psychological testimony inform or influence juror decision making? A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82:178–191. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labov W, Waletzky J. Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. In: Helm J, editor. Essays on the verbal and visual arts. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press; 1967. pp. 12–44. [Google Scholar]

- Laimon RL, Poole DA. Adults usually believe young children: The influence of eliciting questions and suggestibility presentations on perceptions of children’s disclosures. Law and Human Behavior. 2008;32:489–501. doi: 10.1007/s10979-008-9127-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Hershkowitz I, Orbach Y, Esplin PW. Tell me what happened: Structured investigative interviews of child victims and witnesses. West Sussex, UK: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Sternberg KJ, Esplin PW, Hershkowitz I, Orbach Y, Hovav M. Criterion-based content analysis: A field validation study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1997;21:255–264. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(96)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Sternberg KJ, Orbach Y, Esplin P. Age differences in young children’s responses to open-ended invitations in the course of forensic interviews. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:926–934. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal JM, Murphy JL, Asnes AG. Evaluations of child sexual abuse: Recognition of overt and latent family concerns. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller CB, Kirkpatrick LC. Evidence. 4. Austin, TX: Wolters Kluwer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Myers JE, Redlich A, Goodman G, Prizmich L, Imwinkelreid E. Juror’s perceptions of hearsay in child sexual abuse cases. Psychology, Public Policy, & Law. 1999;5:388–419. doi: 10.1037/1076-8971.5.2.388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JEB, Bays J, Becker J, Berliner L, Corwin DL, Saywitz KJ. Expert testimony in child sexual abuse litigation. Nebraska Law Review. 1989;68:1–145. [Google Scholar]

- O’Barr W. Linguistic evidence: Language, power and strategy in the courtroom. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington N, Hastie R. Explaining the evidence: Tests of the story model for juror decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:189–206. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.62.2.189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pipe M, Wilson JC. Cues and secrets: Influences on children’s event reports. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:515–525. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.4.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regan PC, Baker SJ. The impact of child witness demeanor on perceived credibility and trial outcome in sexual abuse cases. Journal of Family Violence. 1998;13:187–195. doi: 10.1023/A:1022845724226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson SA, Dohrenwend BS, Klein D. Interviewing: Its forms and functions. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sas LD, Cunningham AH. Tipping the balance to tell the secret: The public discovery of child sexual abuse. London, Ontario, Canada: London Family Court Clinic; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sayfran L, Mitchell EB, Goodman GS, Eisen ML, Qin J. Children’s expressed emotions when disclosing maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:1026–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saywitz K, Nathanson R. Children’s testimony and their perceptions of stress in and out of the courtroom. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1993;17:613–622. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(93)90083-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saywitz KJ, Goodman GS, Nicholas E, Moan S. Children’s memories of a physical examination involving genital touch: Implications for reports of child sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:682–691. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.5.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow P, Powell M, Murfett R. Getting the story from child witnesses: Exploring the application of a story grammar framework. Psychology, Crime, and Law. 2009;15:555–568. doi: 10.1080/10683160802409347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein NL, Glenn CG. An analysis of story comprehension in elementary school children. In: Freedle RO, editor. New directions in discourse processing. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation; 1979. pp. 53–120. [Google Scholar]

- Vrij A. Criteria-based content analysis: A qualitative review of the first 37 studies. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2005;11:3–41. doi: 10.1037/1076-8971.11.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westcott HL, Kynan S. Interviewer practice in investigative interviews for suspected child sexual abuse. Psychology, Crime, and Law. 2006;12:367–382. doi: 10.1080/10683160500036962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westcott HL, Kynan S. The application of a ‘story-telling’ framework to investigative interviews for suspected child sexual abuse. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 2004;9:37–56. doi: 10.1348/135532504322776843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood B, Orsak C, Murphy M, Cross HJ. Semistructured child sexual abuse interviews: Interview and child characteristics related to credibility of disclosure. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:81–92. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]