ABSTRACT

A 6-year-old Thoroughbred gelding was euthanized after a 2-month period of abnormal neurological signs, such as circling left in his pen and hitting his head and body against the wall. After the horse was euthanized on the farm, a half of the brain and whole blood were submitted for diagnostic tests. Histopathological examination of the brain revealed granulomatous and eosinophilic meningoencephalitis with numerous intralesional nematodes, predominantly affecting the cerebrum. Multifocal malacic foci were scattered in the brain parenchyma. The intralesional parasites were identified as Halicephalobus gingivalis by morphological features and PCR testing. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of meningoencephalitis caused by H. gingivalis in the horse in Korea.

Keywords: Halicephalobus gingivalis, horse, Korea, meningoencephalitis

Neurological diseases in horses are caused by infectious agents, such as viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites [14]. Although parasitic encephalomyelitis in horses is rare, it is a very important cause of neurologic signs. Nematodes that have been identified in the equine central nervous system (CNS) include Halicephalobus gingivalis, Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus equinus, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Setaria spp. and Draschia megastoma. H. gingivalis is a free living soil saprophyte belonging to the nematode order Tylenchida and has the ability to produce extensive tissue damage, because of its migratory behavior [3]. Organs commonly affected by H. gingivalis in horses include the brain, kidneys, lymph nodes, spinal cord, adrenal glands and oral and nasal cavities [9]. However, little is known about the life cycle and method of transmission of this nematode. To date, the disorders caused by this organism have been reported in approximately 50 horses as well as in 1 Grevy’s zebra and 4 humans [6]. In horses, H. gingivalis infections have a wide geographic distribution, including Canada [2], U.S.A. [9], Switzerland [10], Iceland [6], Italy [5], U.K. [8] and Japan [1]. However, in Korea, there has been no report of H. gingivalis infection in horses. Here, we describe the first case of parasitic meningoencephalitis caused by H. gingivalis in a Thoroughbred gelding in Korea.

A 6-year-old Thoroughbred gelding developed acute onset of depression and leaning to the right when disturbed, with no sign of trauma, on July 10, 2012. The gelding was kept with 24 other horses at an equestrian riding club in Busan, Korea, but the other horses were unaffected. History included vaccination against equine influenza and Japanese encephalitis in early 2012 and anthelmintic medication 5 days before onset of clinical signs. The horse was born on the island of Jeju and transported to Busan in 2008.

Despite symptomatic treatment, the condition did not improve, and clinical signs became more severe with circling to the left in the pen and hitting of the head and body against the wall. Because of poor prognosis, euthanasia on the farm was chosen, and only the formalin fixed half of the brain and a whole blood sample were submitted to the Animal Disease Diagnosis Division in Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency for diagnosis. Results of a complete blood cell count of the blood sample revealed leukocytes (including eosinophils) within a normal range.

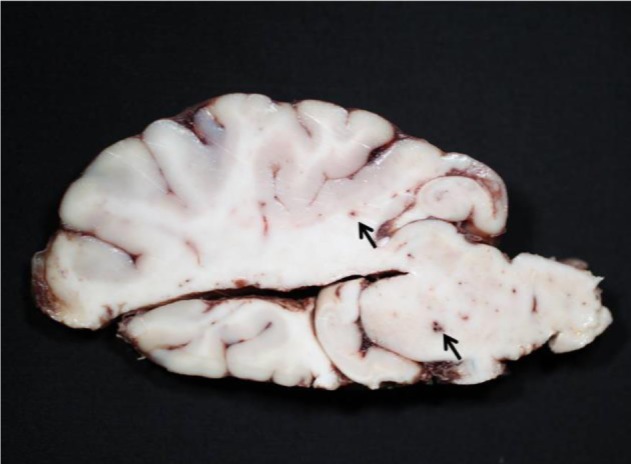

Grossly, multiple red foci were visible on the cut brain surface (Fig. 1). The submitted brain sample was divided into various areas, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4-µm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for microscopic examination.

Fig. 1.

Numerous red foci (arrows) in the cut surface of the brain.

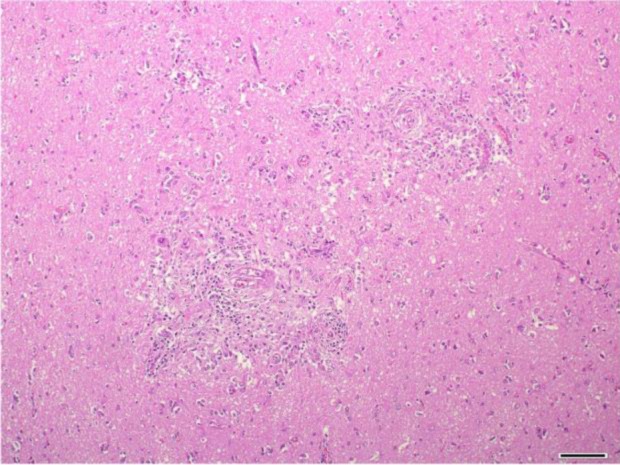

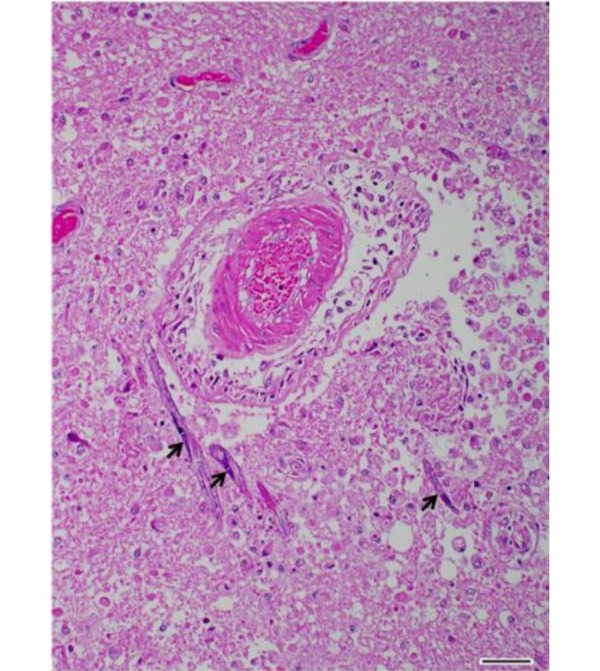

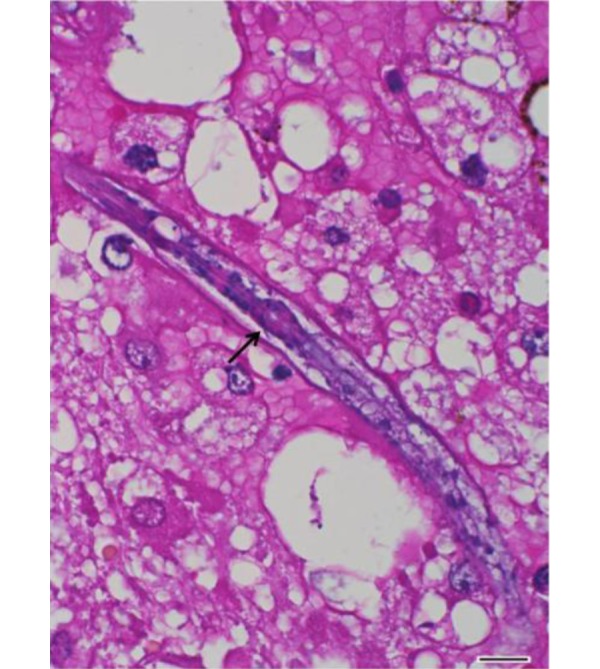

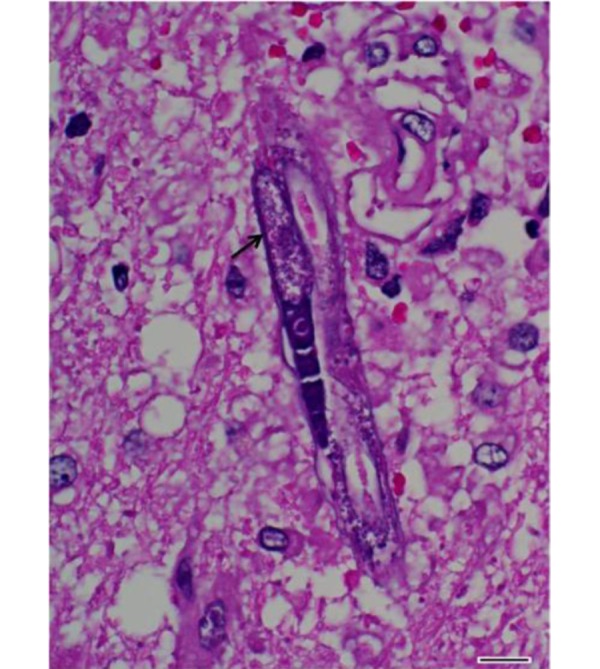

Histopathological examination of the brain revealed granulomatous and eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, predominantly affecting the cerebrum. Multifocal to coalescing granulomatous inflammations were located in the gray and white matters of the cerebrum and consisted mainly of epithelioid cells and lymphocytes (Fig. 2). In the malacic area, numerous gitter cells, axonal swelling and spongiosis were observed. Occasional mineral deposition was scattered throughout the neurophil of the cerebrum. Moderate numbers of eosinophils were infiltrated in the meninges, present in vascular lumens and extended into perivascular spaces. Several nematodes were present within the lesions, predominantly in the perivascular area (Fig. 3). The nematodes had a smooth and thin cuticle, cylindrical body and rhabditiform esophagus composed of a corpus, isthmus and bulb (Fig. 4). An adult female nematode had the typical dorsoflexed ovary and contained an uninucleate ovum (Fig. 5). A few nematodes were also identified in the cerebellum and brainstem. The spinal cord was not submitted; therefore, the presence of lesions in this location could not be confirmed.

Fig. 2.

Cerebrum. Granulomatous inflammation around the blood vessels. HE. Bar=100 µm.

Fig. 3.

Cerebrum. Severe encephalomalacia with numerous nematodes (arrows) in perivascular area. HE. Bar=50 µm.

Fig. 4.

Cerebrum. A nematode with characteristic rhabditiform esophagus including corpus, isthmus and bulb (arrow). HE. Bar=10 µm.

Fig. 5.

Cerebrum. Longitudinal section of an adult female of H. gingivalis containing an uninucleate ovum (arrow). HE. Bar=10 µm.

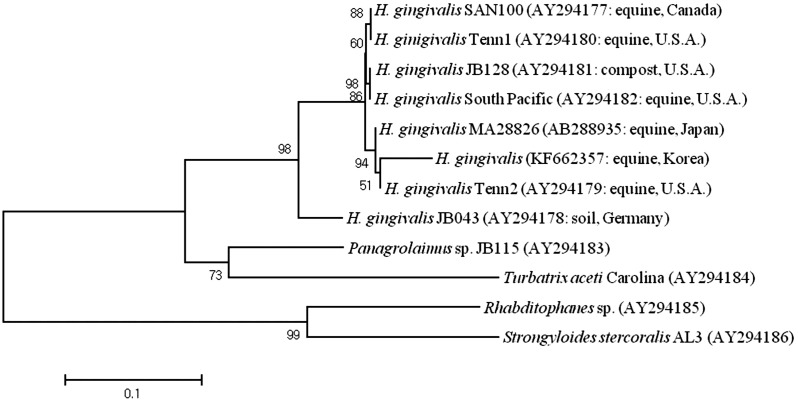

For parasitic species identification, genomic DNA was extracted from paraffin embedded blocks using a QIAamp DNA FFPF Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The nuclear large subunit ribosomal RNA gene (LSU rDNA) was amplified by PCR using primers #391 and #501 [11]. The PCR product was purified using a QIAamp Purification kit (Qiagen) and subjected to commercial sequencing (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea) using primers, #391, #504, #501 and #503 [11]. For phylogenetic analysis, sequences were aligned by the BioEdit program (Ver. 7.1.9; Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.). Rhabditophanes sp., Panagrolaimus sp., Strongyloides stercoralis and Turbatrix aceti were used for comparison as outgroup species [11]. The aligned data were analyzed by MEGA 5 software [13]. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the nematode in this case belonged to a same clade with H. gingivalis isolates from the Japan, U.S.A., Canada and Germany (Fig. 6). This nematode showed the highest identity (97.6%) to the isolate MA28826 from Japan and Tennessee 2 from U.S.A. PCR testing was performed to screen for the following neurotropic viral infections, and the results were negative: Japanese encephalitis with Abortion Multi RT-PCR II (Median, Chuncheon, Korea), West Nile virus [17] and equine herpesvirus types 1 and 4 [4].

Fig. 6.

Maximum likelihood tree based on the LSU rDNA of the eight H. gingivalis and outgroups. Numbers in parentheses indicate the GeneBank accession number and the origin of the isolate. A statistical support was provided by bootstrapping over 1,000 replicates. The scale bar indicates 0.1 amino acid substitutions per site.

On the basis of histopathological features and parasitological findings, this case was diagnosed as meningoencephalitis caused by H. gingivalis. H. gingivalis (formerly Micronema deletrix) is a small nematode of the order Tylenchida (formerly Rhabditata) and family Panagrolaimidae. The genus Halicephalobus consists of 9 species: H. gingivalis, H. limuli, H. similigaster, H. minutum, H. parvum, H. palmaris, H. intermedia, H. laticauda and H. brevicauda [1]. These nematodes are free living, saprophytic organisms and are commonly found in soil, manure and decaying humus [9, 11]. To date, only female H. gingivalis parasites have been identified in mammalian tissue samples [10].

The life cycle, route of infection and pathogenesis of this nematode are poorly understood. The route of infection in humans appears to be manure-contaminated skin lacerations [10]. In horses, postulated routes of infection include skin and mucous membrane penetration with subsequent invasion of the sinuses and bones of the head and later hematogenous dissemination to internal parenchymal tissues [3, 9, 11]. Prenatal, postnatal and transmammary infections have also been described [12, 16]. In this patient, no skin laceration, oral granuloma or specific lesions on the head were detected on clinical observation. Further, because only the brain sample was examined, the exact route of infection of the parasites could not be determined. However, the nematodes were predominantly detected in the perivascular area of the brain, which could suggest a hematogenous route of infection. Similar infectious route also has been suggested in the previous reports [2, 3, 8, 15].

Clinical signs associated with H. gingivalis infection are variable and depend on the organ or system affected. In horses, this nematode has a predilection for brain, kidney, lymph node, spinal cord, eye, lung, maxilla and mandible [9]. In the cases of CNS involvement, clinical signs include depression, ataxia, leaning against objects and loss of balance. However, antemortem diagnosis is very difficult in the absence of granulomatous skin, oral or renal lesions, and diagnosis of neurological halicephalobosis is made by histopathological examination of tissues at necropsy [11].

In horses showing abnormal neurological signs, etiological agents, such as viruses, bacteria, parasites and toxic substances, should be considered. In this case, the lesions caused by viruses and bacteria were not observed, and these pathogens were not detected. Other neurotropic parasites (e.g. A. cantonensis, S. vulgaris and Setaria spp.) were differentiated from H. gingivalis on the basis of morphological and genetic findings.

Horses with neurological involvement of H. gingivalis infection generally undergo rapid and progressive neurological deterioration, which progresses rapidly to death. Effective treatment is very difficult, and there are no guidelines for the prevention of this nematode. Unsuccessful treatment may be due to the inability of anthelmintic drugs to cross the blood-brain barrier and penetrate parasitic granulomas [15]. Although there is a report of successful treatment of H. gingivalis infection in 3 horses, none of them had CNS lesions [7].

In this case, the affected horse was born and raised for 6 years in Korea. There was no history of transportation to other countries. This means that the horse acquired H. gingivalis in Korea; a further study is warranted to clarify the distribution and prevalence of this parasite. In addition, equine veterinarian should consider H. gingivalis infection as a differential diagnosis of neurological disease in horses in Korea.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akagami M., Shibahara T., Yoshiga T., Tanaka N., Yaguchi Y., Onuki T., Kondo T., Yamanaka T., Kubo M.2007. Granulomatous nephritis and meningoencephalomyelitis caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis in a pony gelding. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 69: 1187–1190. doi: 10.1292/jvms.69.1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bröjer J. T., Parsons D. A., Linder K. E., Peregrine A. S., Dobson H.2000. Halicephalobus gingivalis encephalomyelitis in a horse. Can. Vet. J. 41: 559–561 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant U. K., Lyons E. T., Bain F. T., Hong C. B.2006. Halicephalobus gingivalis-associated meningoencephalitis in a Thoroughbred foal. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 18: 612–615. doi: 10.1177/104063870601800618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crabb B. S., Studdert M. J.1995. Equine herpesviruses 4 (equine rhinopneumonitis virus) and 1 (equine abortion virus). Adv. Virus Res. 45: 153–190. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60060-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Francesco G., Savini G., Maggi A., Cavaliere N., D’Angelo A. R., Marruchella G.2012. Equine meningo-encephalitis caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis: a case report observed during West Nile disease surveillance activities. Vet. Ital. 48: 437–442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eydal M., Bambir S. H., Sigurdarson S., Gunnarsson E., Svansson V., Fridriksson S., Benediktsson E. T., Sigurdardóttir Ó. G.2012. Fatal infection in two Icelandic stallions caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis (Nematoda: Rhabditida). Vet. Parasitol. 186: 523–527. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson R., van Dreumel T., Keystone J. S., Manning A., Malatestinic A., Caswell J. L., Peregrine A. S.2008. Unsuccessful treatment of a horse with mandibular granulomatous osteomyelitis due to Halicephalobus gingivalis. Can. Vet. J. 49: 1099–1103 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermosilla C., Coumbe K. M., Habershon-Butcher J., Schöniger S.2011. Fatal equine meningoencephalitis in the United Kingdom caused by the panagrolaimid nematode Halicephalobus gingivalis: case report and review of the literature. Equine Vet. J. 43: 759–763. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinde H., Mathews M., Ash L., St Leger J.2000. Halicephalobus gingivalis (H. deletrix) infection in two horses in southern California. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 12: 162–165. doi: 10.1177/104063870001200213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller S., Grzybowski M., Sager H., Bornand V., Brehm W.2008. A nodular granulomatous posthitis caused by Halicephalobus sp. in a horse. Vet. Dermatol. 19: 44–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadler S. A., Carreno R. A., Adams B. J., Kinde H., Baldwin J. G., Mundo-Ocampo M.2003. Molecular phylogenetics and diagnosis of soil and clinical isolates of Halicephalobus gingivalis (Nematoda: Cephalobina: Panagrolaimoidea), an opportunistic pathogen of horses. Int. J. Parasitol. 33: 1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00134-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spalding M. G., Greiner E. C., Green S. L.1990. Halicephalobus (Micronema) deletrix infection in two half-siblings foals. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 196: 1127–1129 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S.2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28: 2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toth B., Aleman M., Nogradi N., Madigan J. E.2012. Meningitis and meningoencephalomyelitis in horses: 28 cases (1985–2010). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 240: 580–587. doi: 10.2460/javma.240.5.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trostle S. S., Wilson D. G., Steinberg H., Dzata G., Dubielzig R. R.1993. Antemortem diagnosis and attempted treatment of (Halicephalobus) Micronema deletrix infection in a horse. Can. Vet. J. 34: 117–118 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkins P. A., Wacholder S., Nolan T. J., Bolin D. C., Hunt P., Bernard W., Acland H., Del Piero F.2001. Evidence for transmission of Halicephalobus deletrix (H. gingivalis) from dam to foal. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 15: 412–417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeh J. Y., Lee J. H., Seo H. J., Park J. Y., Moon J. S., Cho I. S., Lee J. B., Park S. Y., Song C. S., Choi I. S.2010. Fast duplex one-step reverse transcriptase PCR for rapid differential detection of West Nile and Japanese encephalitis viruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48: 4010–4014. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00582-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]