Abstract

Over 1.8 million people have died of AIDS in South Africa and it continues to be a death sentence for many women. The purpose of this study was to examine the broader context of death and loss from HIV/AIDS and to identify the cultural factors that influenced existing beliefs and attitudes. The participants included 110 women recruited from three communities in South Africa. Focus group methodology was used to explore their perceptions surrounding death and loss from HIV/AIDS. Using the PEN-3 cultural model, our findings revealed that there were positive perceptions related to how women cope and respond to death and loss from HIV/AIDS. Findings also revealed existential responses and negative perceptions that strongly influence how women make sense of increasing death and loss from HIV/AIDS. In the advent of rising death and loss from HIV/AIDS, particularly among women, interventions aimed at reducing negative perceptions while increasing positive and existential perceptions are needed. These interventions should be tailored to reflect the cultural factors associated with HIV/AIDS.

It has been well documented that HIV/AIDS remains a leading cause of death and mortality among people living in South Africa; over 1.8 million people have died of AIDS (Bachmann & Booysen, 2003; Bradshaw, Laubscher, Dorrington, Bourne, & Timaeus, 2004; Dorrington, Bourne, Bradshaw, Laubscher, & Timaeus, 2001). South African women are disproportionately affected according to existing data, which indicate a significant number of adult deaths (Bradshaw et al., 2004). Also, Schatz and Ogunmefun (2007) found that older South African women often provided crucial financial, physical, and emotional support for their ill adult children and they fostered orphaned grandchildren in their homes. Given that death and loss from HIV/AIDS continues to remain a major public health issue in South Africa, it is important to understand its cultural implications.

We can learn important lessons from existing studies on death and loss from HIV/AIDS, particularly among gay individuals and women in other countries. For example, in describing how HIV positive gay men make sense of AIDS, Schwartzberg (1993) found that in some instances, although HIV/AIDS was a catalyst for personal growth and increased a sense of belonging, it also led to irreparable loss, a contamination of one's self, isolation, and a confirmation of one's powerlessness. In another study conducted among gay individuals in a large urban area, Carmack (1992) found that a balance between engagement and detachment was critical in explaining how participants coped with multiple AIDS-related losses. In describing AIDS-related grief and coping with loss among HIV positive men and women in the U.S., Sikkema and colleagues (2003) found that women exhibited higher levels of anxiety and were more likely to report higher levels of traumatic stress.

Most of the research on death and loss from HIV/AIDS has explored the experiences of people living in western societies. One study provided preliminary comparative data on the issues of AIDS-related bereavement in the U.S. and South Africa (Demmer & Burghart, 2008). In this study, they found that stigma, lack of support, dealing with one's own HIV status, and the need to focus on economic survival were critical in explaining the way people respond to and cope with AIDS-related death across the two countries. Also, there were similarities in the bereavement experiences of participants in the two countries. Although this study and the vast body of evidence on AIDS-related bereavement consistently stressed the importance of understanding how people cope with HIV/AIDS, the cultural implications of death and loss from HIV/AIDS are inadequately addressed. This raises several important questions with women in particular and their experience of the HIV/AIDS stigma and in cases in which HIV/AIDS represents irreparable loss and isolation. Moreover, the burden placed on women to care for the sick and to deal with AIDS-related loss (such as loss of male partners) (Demmer, 2007) warrants further attention in South Africa from a cultural perspective.

That HIV/AIDS is associated with high levels of stigma, denial, and shame is well established in the literature (Demmer, 2007; Kittikorn, Street, & Blackford, 2006; Parker & Aggleton, 2003) and the role of traditional and socio-cultural norms in shaping how South African women care for loved ones with HIV/AIDS have been previously discussed (Demmer, 2006). However, an area of key concern is that the majority of the literature highlights only the negative challenges experienced by women, with little or no reference to the positive and unique responses used to cope with the disease. For example, although some family members may experience feelings of shame when a relative contracts AIDS (Kittikorn et al., 2006), rarely discussed are the positive and unique coping mechanisms such as notions of hope (Eliott & Olver, 2007), discovery of beneficial and life-affirming aspects of coping with severe illness (Schwartzberg, 1993) and the belief in life even after a seropositive status. This is particularly important if positive and unique responses are to be used as a mechanism for reducing AIDS stigma in South Africa.

In addition, available studies often do not recognize that death and loss from HIV/AIDS have altered the position of women in many societies as many now assume the role of breadwinners, a role traditionally held by men. If the rise in the number of deaths continues to remain unabated in South Africa (Bradshaw et al., 2004), it is important to explore the cultural impact of death and loss from HIV/AIDS among women. The qualitative study presented here was carried out among women living in three communities in South Africa. Using the PEN-3 cultural model as a guide, it aimed to examine from a cultural perspective the impact of death and loss from HIV/AIDS among women.

Theoretical Framework: The PEN-3 cultural model

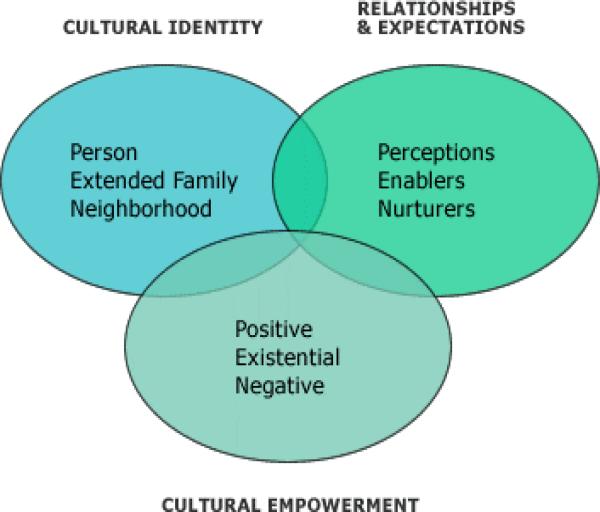

Considering the limited understanding of the cultural implications of death and loss from HIV/AIDS, a key question is whether cultural aspects of death might influence perceptions surrounding death from AIDS that are positive, existential (unique), or negative as advanced in the PEN-3 cultural model. The PEN-3 cultural model developed by Airhihenbuwa (1995, 2007) offers cultural lenses through which to examine and understand various relationships and expectations that collectively influence decisions about health and life at the levels of the person, such as a mother, extended family and the community (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2009). It also allows for an exploration of cultural values and practices that could be encouraged, acknowledged, and/or discouraged. With the PEN-3 cultural model, the notion that positive perceptions might surround death in the context of HIV and AIDS may seem problematic as death (by definition) is often viewed with a negative lens. But, from an African cultural context, death may be positively viewed as celebration of life, a “part of the natural rhythm of life” (Mbiti, 1969, p. 151), particularly in the contexts of the belief in life after death. The belief in life after death also conditions cultural rituals that are celebrated in funerals, particularly in cases in which the deceased had lived a long life.

The PEN-3 cultural model of consists of three domains: Relationship and Expectations, Cultural Empowerment, and Cultural Identity.

The Relationships and Expectations domain examines women's perceptions about death and loss from HIV/AIDS, the resources and health care services that promote or discourage their coping response, as well as the influence of family and kin in nurturing practices and expectations such as with caring for ill relatives. With the Cultural Empowerment domain, the lived experiences of women are also taken into consideration by examining coping responses that are positive, existential (unique), and negative. In this way, cultural beliefs and practices that influence responses to death and loss from HIV/AIDS are examined so that aspects that are beneficial are supported, those that are harmless are acknowledged, and practices that are harmful and have negative health consequences are tackled. Following the identification of these health beliefs and actions, the Cultural Identity domain highlights the intervention points of entry. These may occur at the level of persons (e.g., mother or grandmother), extended family members, or neighborhood/village.

The PEN-3 cultural model has been used to study stigma, culture, and HIV/AIDS in Western Cape South Africa (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2009), the cultural and racial contexts of “othering” as it relates to HIV and AIDS stigma (Petros, Airhihenbuwa, Simabyi, Ramaglan, & Brown, 2006), the role of family systems with care and support of people living with HIV/AIDS (Iwelunmor, Airhihenbuwa, Okoror, Brown, & BeLue, 2007), and why motherhood matters with HIV/AIDS disclosure patterns among women living with HIV/AIDS (Iwelunmor, Zungu, & Airhihenbuwa, 2010). It has also been utilized to examine the sociocultural factors associated with health and health care-seeking among Latina immigrants (Garces, Scarinci & Harrison, 2006), the sociocultural factors associated with cigarette smoking among women in Brazil (Scarinci, Silveira, Dos Santos, & Beech, 2007), nutrition influences and birth outcomes (Kannan, Webster, Sparks, Acker, Greene-Moton, Tropiano et al. 2009), and the prevention of type 2 diabetes (Grace, Begum, Subhani, Kopelman & Greenhalgh, 2008), and to design culturally appropriate breast and cervical cancer screening programs for women (Erwin, Johnson, Trevino, Duke, Feliciano, & Jandorf, 2007) as well as prostate cancer screening for men (Lewis, 2005). To date, the PEN-3 cultural model has not been applied with an understanding of the cultural implications of death and loss from HIV/AIDS. As a result, this study focused on the Relationships and Expectations that matter with death and loss from HIV/AIDS. Also, the possibilities of culture with reference to not only positive and existential (unique) responses but also an understanding of the negative responses (Cultural Empowerment Domain) related to coping with death and loss from HIV/AIDS are also explored.

Methods

Design

This paper presents an analysis of focus group discussions conducted during the second year of a large study of HIV and AIDS stigma in South Africa (see Airhihenbuwa et al., 2009). Specifically, this paper examines 12 focus group discussions conducted separately with women living with HIV and AIDS and female family members of persons living with HIV and AIDS. The focus group discussions were conducted in Khayelitsa, Mitchell's Plain, and Gugulethu, South Africa, which are located in the Western Cape region of the country. The focus group discussion guides were determined beforehand by the research team both from the Pennsylvania State University and South Africa. Probes were used in the interviews as required. Also, based on the three predominant languages spoken in the Western Cape, each focus group interview was conducted either in English, Xhosa, or Afrikaans. The focus groups were audio-taped with the participants' permission and discussions conducted in Xhosa and Afrikaans were first transcribed and then translated into English. The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees at Penn State and the Human Sciences Research Council in South Africa.

Participants

A total of 110 women participated in the focus group discussions. A purposive sampling approach was used to identify and recruit eligible participants for the focus groups. These participants were recruited from HIV and AIDS support groups located in the three communities in Western Cape. Although, the majority of the participants (67) were female family members of people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA), 43 women living with HIV and AIDS participated in the focus group discussions. The focus group discussions with female family members of people living with HIV/AIDS and women living with HIV/AIDS were conducted separately. Demographic information such as age or marital status were not recorded, even though based on the focus groups, it is apparent that participants varied in age and most were single.

Data Analysis

Although the primary focus of the larger study was to investigate HIV/AIDS stigma in South Africa (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2009), it was during analysis of the focus group transcripts that themes related to death and loss from HIV/AIDS warranted further attention. What was particularly salient was that death and loss was the first thing that participants thought of when they responded to the questions on HIV and AIDS stigma. Moreover, these perceptions were similar for both women living with HIV/AIDS and female family members of people living with HIV/AIDS. As a result, we sought to explore whether these assertions could explain how people coped with HIV/AIDS, whether there were relationships and expectations that mattered or whether it generated positive, existential (unique) or negative responses. To illuminate the ways in which women make sense of death and loss from HIV/AIDS, the PEN-3 cultural model was used as a guide with data analysis of the transcripts. Specifically, each focus group transcript was loaded into Nvivo 7.0, a software package used to organize qualitative data. Following the focus group analysis steps outlined by Creswell (2007), each transcript was repeatedly examined and cross-compared in their entirety to identify major organizing ideas. These organizing ideas were then thematically described, classified, and interpreted into codes or categories (Creswell, 2007). The resulting categories were then reduced into themes that corresponded with the Relationship and Expectations (specifically, perceptions) and Cultural Empowerment (positive, existential and negative) domains of the PEN-3 cultural model.

Results

Positive Perceptions

In describing positive perceptions, Airhihenbuwa (2007) suggested that this category reflects factors that promote health behavior of interest. Participants' responses that were categorized as positive perceptions of death and loss from HIV/AIDS included statements that reflected the possibilities of treatments with HIV/AIDS, the notion that HIV is like other diseases, hope and optimism about the future, as well as acceptance of seropositive status.

Possibilities of treatment

In our focus group discussions, participants remarked that people living with HIV/AIDS should not consider HIV and AID a death sentence because there is treatment. Some participants stated that treatment allowed people living with HIV and AIDS to cope well with the disease. Participants noted that every disease kills because death is for everybody; however, the potential for surviving any disease such as HIV and AIDS involved taking one's treatment because doing so enables PLWHA to live a long life. As one woman living with HIV/AIDS simply stated: “When people hear about HIV and AIDS they must not think about death because there is still so many years ahead of you, there is treatment and people should take treatment so that they can live longer.”

HIV/AIDS is like any other disease

In addition, positive perceptions surrounding death within the context of HIV/AIDS were linked to the notion that “HIV/AIDS is like any other disease.” One participant stated that with HIV/AIDS, “you live with it as if it is a cold.” Indeed, there was a sense that HIV and AIDS was like any chronic disease such as high blood pressure and therefore is treatable “when you take treatment as required you live for a long time.” When the focus group facilitator asked participants to discuss why HIV should be considered like any other disease, a family member of a PLWHA replied:

Even high blood pressure kills you know, all of them kill when one doesn't treat them with right precautions. When you take treatment as required you live for a long time until you die as you have to because death is for everybody.

Hope and optimism about the future

It has been well documented that notions of hope are pivotal in coping with as well as alleviating any negative experiences of living with HIV. This was true for participants who believed that with HIV, it is important for PLWHA to “gain hope so that you live for a long time.” Optimism about one's future was closely linked to the ability to think positively about living with HIV/AIDS. The following statement from a woman living with HIV/AIDS helps to demonstrate notions of optimism about the future in the context of living with HIV/AIDS: “When I think of this virus, I feel positive, so the thing that thing I think about is my future. I don't think about staying indoors and not wanting people to visit you because you are HIV positive….”

Acceptance of seropositive status

In our focus group discussions, one of the most prominent findings was acceptance of seropositive status. Acceptance of one's HIV seropositive status was expressed in terms of living day by day with HIV, rather than thinking “that you are going to die in 10–15 years.” As one woman living with HIV/AIDS explained, “even if I have the virus I should accept it and treat it the way you are supposed to treat it.”

Existential Perceptions

According to Airhihenbuwa (1995, 2007), existential perceptions are the qualities of a culture that make it unique. Airhihenbuwa (1995, p. 34) suggested that these qualities “comprise those beliefs, practices, and behaviors that are indigenous to a group.” They are often misunderstood by outsiders, but yet they have no harmful health consequence (Airhihenbuwa, 1995, 2007). In the focus group discussions, responses that were categorized as existential perceptions surrounding death within the context of HIV/AIDS form the core of the cultural meanings of death, particularly for women. Research on health behaviors typically focus on the negative, yet our findings revealed more existential meanings of death and they were tied to the belief that HIV is not the end of life and that there is life even after death (in this case life, even after knowledge of a seropositive status). Also, perceptions related to death as a form of relief were among the existential responses generated during the focus group discussions.

HIV is not the end of life

In our focus group discussions, counteracting the often negative perceptions surrounding HIV/AIDS were the participants' beliefs that HIV and AIDS “is not the end of life.” Participants noted that although HIV was pervasive in their communities and PLWHA often experienced various forms of stigma and discrimination, it important for PLWHAs' to understand that their seropositive status was “not the end of one's life.” One focus group participant expressed that although the news of her HIV seropositive status felt like the end of the world, she became a member of TUAP (Tafelsig United Aids Project) and she “started to see things in a different way.” TUAP is an organization that provides support for people living with HIV/AIDS and was significant in enabling her to perceive that HIV/AIDS was not the end of her life, as described below:

To me it was like the end of the world like there isn't life after this and this is death and there's no life after death and when I became a TUAP member, I started to see things in a more different way and I saw, no, you can live a normal life and there is life after this….

Life after HIV

Even when HIV was associated with death, the belief in the persistence of life was a common theme generated from the focus group discussions. This belief is also consistent with the African notion of life after death (Opoku, 1989). For one participant, the reality of living with knowledge of a seropositive status was tied to the belief that, “there is life after death,” in this case, life after discovering that one is HIV positive. This notion was also supported by a strong sense of belief in being reborn. As another participant remarked, rather than believing that HIV seropositive status was the end of one's life, she accepted her HIV seropositive status and “it was like a new life I had to start. I was reborn again….”

Death as a form of relief

Some family members of PLWHA stated that their relatives living with HIV/AIDS were viewed as being dead in part because of the unpredictable nature of their pain and suffering as well as overall sickness from HIV. Thus, when they come across a relative living with HIV/AIDS, the first thing that comes to mind is death. The emotional turmoil of watching family members living with AIDS endure pain evoked a sense of relief, particularly when PLWHA eventually dies. Family members remarked that it was painful to watch PLWHA as they struggled and groaned. In describing this sense of relief, a family member remarked that when a female relative was sick at home:

You know that she is in pain as she struggles a lot, while groaning every time. When that time comes when she closes her eyes and leaves this world, you feel free because you know now that she is at rest and you feel relieved you know…

Negative Perceptions

In our focus group discussions, negative perceptions surrounding death within the context of HIV/AIDS were linked to what Airhihenbuwa (2007) described as the beliefs and actions that are harmful to health. Indeed, participants' responses related to the belief in HIV/AIDS as a death sentence was the theme that defined the negative perceptions category.

HIV is a death sentence

As participants living with HIV/AIDS grappled with coming to terms with their seropositive status, the belief that HIV/AIDS was a death sentence was evident in their perceptions of death and loss from HIV/AIDS. Some participants believed that for those with HIV/AIDS, death frequently came to mind as living with a seropositive status signaled the “end of everything,” particularly “as it becomes difficult to continue with life….” One participant noted that she knew her efforts would not be the same again. She simply believed that “I am going to die irrespective of what I do, and that is the only thing I should wait for.” Another participant living with HIV/AIDS stated that:

Ok, personally I think it is only death that frequently comes to my mind which is end of everything. It becomes difficult to continue with life anymore and the fact that I am HIV positive becomes situated and entrenched in my mind….

When asked to further discuss why HIV/AIDS was a death sentence, one participant living with HIV/AIDS explained that: “It is because you don't imagine yourself getting infected. You always think that it is for other people, so when you become HIV infected you only think of one thing and that is death.”

These perceptions were strikingly similar for family members, as they believed that HIV/AIDS was a death sentence for PLWHA. One female family member of a PLWHA remarked that with HIV/AIDS: “The first thing that comes in my mind is death…I think about it because I see when somebody is sick with AIDS and how that person looks like you see now I just think about death.” For this participant, the harm is not so much that people die from AIDS, because they do. The harm is in seeing HIV/AIDS as a death sentence for everyone with the virus. The harm is in the sweeping condemnation of PLWHA. In describing why family members hold these views, another family member explained that: “When I think about a person who is said to have HIV/AIDS…it is as if she has AIDS and there is nothing else, and the only thing to do is to die.”

Discussion

Using the PEN-3 cultural model, this paper examined the cultural perceptions surrounding death and loss from HIV/AIDS in three communities in South Africa. Although we do not claim to have provided an exhaustive view on cultural aspects of death within the context of HIV/AIDS, it is worth noting that few attempts have been made to address these perceptions from a cultural perspective in the South African context. To this end, our findings highlight several key points. First, the findings confirm that some people living with HIV/AIDS do not view knowledge of their HIV seropositive status as a death sentence. Instead, our focus group findings revealed that there were positive perceptions surrounding the notions of death and loss from HIV/AIDS. These perceptions were influenced by the use of HIV/AIDS treatment, the ability to perceiving HIV/AIDS like other diseases, hope and optimism about one's future, and acceptance of one's HIV seropositive status.

Previous literature on HIV/AIDS-related loss has shown similar findings in the U.S. (Rogers, Hansen, Levy, Tate, & Sikkema, 2005) and in Indonesia (Damar, 2009). For example, among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S., Rogers and colleagues (2005) found that optimism predicted the use of active coping strategies such as positive reinterpretation of loss. Damar's (2009, p. 97) study on HIV/AIDS-related loss in Indonesia found that “elements of acceptance were present in the narratives of the women and it coincided with a re-evaluation of their role as primary caretakers.” Also, hope is important in that it enables PLWHA to “believe life to be worth living at the present and in the future” (Kylmä, Vehviläinen-Julkunen & Lähdevirta , 2001, p. 768). These findings suggest that there are similarities in the way people respond to and cope with death and loss from HIV/AIDS in different countries. Because AIDS is a global epidemic, a better understanding of these positive perceptions would allow for the development of appropriate interventions aimed at helping people around the world cope with increasing death and loss from HIV/AIDS (Demmer & Burghart, 2008).

Second, our findings revealed that existential views surrounding HIV/AIDS provided a window into cultural aspects of death and loss from HIV/AIDS. For example, it has been previously suggested that the African value of life after death is linked to the notion that “death does not lead to the destruction of either the person or the identity of the deceased” (Opoku 1989, p. 17). Instead, “human life is part of an ongoing reality, and each death is a re-assimilation into the reality of the world” (Opoku, 1989, p. 18). In the context of death and loss from HIV/AIDS, these views were consistent with the perceptions shared by participants as they also believed that HIV/AIDS was not the end of one's life as people living with HIV/AIDS can continue to enjoy life even after learning of their HIV seropositive status. Also, issues related to HIV/AIDS death as a form of relief were critical in shaping existential perceptions of women in this study. The emotional toll on family members of PLWHA is enormous as they observe the pain and suffering endured by the PLWHA before they ultimately succumb to death from AIDS (Brown & Powell-Cope, 1993). Family members' belief that death is a form of relief invariably becomes their unique response to the eventual loss of family from HIV.

Finally, negative perceptions of death from HIV/AIDS were synonymously linked to the belief that HIV/AIDS status signaled the end of one's life -- a “death sentence.” Previous literature among people living in South Africa has shed some light on how newly infected persons with HIV are “tainted with death.” In that study, Niehaus (2007, p. 854) argued that the representation of persons living with HIV and AIDS as being “dead before dying” and their symbolic location in an abnormal domain between life and death is more likely the main source of the stigma often experienced by people living with HIV and AIDS as well as their family and community members. These findings are critical in explaining not only the negative perceptions commonly held in relation to death and loss from HIV/AIDS, but also the experience of HIV/AIDS stigma. Although negative perceptions have shaped the way some people respond to and cope with HIV/AIDS-related death and loss, we extend available evidence by offering insights into the positive and existential perceptions that are equally important and often overlooked.

The positive and existential statements highlighted in this study underscore the fundamental importance of understanding beneficial perceptions that should be encouraged as well as beliefs that are unique to a group and pose no threat to health. Indeed, it is not surprising that the general appraisal that “HIV is like any other disease,” may serve as a catalyst for acceptance of seropositive status while conferring hope and optimism for the future. It may also transform the challenges associated with HIV/AIDS into the belief that there is a life worth living even when faced with a traumatic event. If researchers are truly motivated to avert the negative perceptions women hold about themselves in the context of death and loss from HIV/AIDS, the task therefore is to broaden investigations to include knowledge of positive and existential perceptions.

The results of this study have important implications not only for how individuals living with HIV/AIDS perceive their illness, but also for how affected family and community members socially construct and respond to HIV/AIDS. Indeed, a better understanding of all perceptions is important as it is possible that death and loss from AIDS may undermine effective HIV treatment and care and voluntary counseling and testing. It may also decrease disclosure of seropositive status and adherence to antiretroviral treatment, and derail efforts to stem the spread of new HIV infections. In the absence of effective treatment, and given the statistics on AIDS related death in South Africa, how people make sense of HIV and AIDS is relevant particularly in the context of addressing effective treatment and care and the support needs of PLWHA as well as their family and community members. Having framed these perspectives into their relevant contexts, their utility as an intervention entry point (Airhihenbuwa, 1995, 2007) is likely to not only address the needs of the PLWHA (as well as their family and community members), but also lead to significant changes in beliefs and attitudes toward death and loss from HIV/AIDS.

Although the results have potential uses, some study limitations are worth mentioning. First, because of our small sample size and because participants were recruited purposively from local support groups in Colored communities in South Africa, the findings may not represent the experiences of South Africans in other communities such as in Black Afrikaan communities of Limpopo Province or among Indian South Africans in Durban. Social desirability may also influence responses as tradition often emphasizes respect for the elderly in most African societies. Thus, it is possible that the views of younger participants are not fully represented as they may have chosen not to disagree with the older female participants in the study. Moreover, there is a possibility that the findings presented here may not provide an in-depth understanding of death and loss from HIV/AIDS as it is based on a larger project on HIV/AIDS stigma.

On the other hand, from the focus group discussions it was evident that for many of the women, death and loss from HIV/AIDS are linked with understanding HIV/AIDS stigma. Also, using the PEN-3 cultural model, the insights generated from this study suggest that there is value in considering the role of positive and existential perceptions in shaping responses to death and loss from HIV/AIDS. The findings presented here are only a first step in understanding the cultural implications of death and loss from HIV/AIDS. Although this paper focused on perceptions (in the Relationship and Expectations domain), other topics such as issues related to enablers (structural or societal support), and nurturers (reinforcing factors influenced by significant others) require further attention from researchers.

In conclusion, the findings presented here demonstrate the need to take into account varying perceptions of death and loss from HIV/AIDS. Indeed, it is in understanding all perceptions (positive, existential, and negative) and in exploring the contexts in which they occur that researchers can begin to effect change by discouraging the negative perceptions associated with death and loss from HIV/AIDS. Such efforts will only begin when perceptions that are beneficial are encouraged and perceptions that pose no threat are acknowledged (Airhihenbuwa, 2007). In a country in which the statistics on death and loss from HIV/AIDS among women indicate that the trend continues unabated (Bradshaw et al., 2004), interventions aimed at reducing negative perceptions while increasing positive and existential perceptions are needed. These interventions should be tailored to reflect the cultural factors associated with HIV/AIDS. The PEN-3 cultural model offers an opportunity to examine the range of relationships and expectations as well as values and practices that matter in understanding perceptions related to death and loss from HIV/AIDS.

Figure 1.

The PEN-3 Cultural Model

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, No. R24 MH068180. We thank the following students for participating in data collection: Vuyisile Mathiti, Heidi Wichman, Tshipinare Marumo, Shahieda Abrahams, Thandiwe Chihana, Nashrien Khan, Roro Makubalo, Xolani Nibe, Gail Roman, Matlakala Pule, and Nadira Omarjee. For human participant protection, the study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of Penn State University and the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Health and culture: Beyond the Western paradigm. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Healing our differences: The crisis of global health and the politics of identity. Rowan & Littlefield; Lanham, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Okoror TA, Shefer TS, Brown D, Iwelunmor J, Smith E, et al. Stigma, culture, and HIV and AIDS in the Western Cape, South Africa: An application of the PEN-3 Cultural Model for community based research. Journal of Black Psychology. 2009;35:407–432. doi: 10.1177/0095798408329941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann MO, Booysen FL. Health and economic impact of HIV/AIDS on South African households: A cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2003;3:14, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw D, Laubscher R, Dorrington R, Bourne DE, Timæus IM. Unabated rise in the number of adult deaths in South Africa. South African Medical Journal. 2004;94(4):278–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Powell-Cope G. Themes of loss and dying in caring for a family member with AIDS. Research in Nursing and Health. 1993;16:179–191. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmack BJ. Balancing engagement/detachment in AIDS-related multiple losses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1992;24:9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1992.tb00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Damar AP. Doctoral Dissertation. 2009. Need analysis for AIDS-related bereavement counseling programmes to assist women affected by HIV/AIDS -- An Indonesian perspective. Retrieved from http://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/1348. [Google Scholar]

- Demmer C. Caring for a loved one with AIDS: A South African Perspective. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2006;11:439–455. [Google Scholar]

- Demmer C. Responding to AIDS-Related bereavement in the South African context. Death Studies. 2007;31:821–843. doi: 10.1080/07481180701537287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmer C, Burghart G. Experiences of AIDS-related bereavement in the USA and South Africa; A comparative study. International Social Work. 2008;51:360–370. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrington R, Bourne D, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R, Timaeus IM. The impact of HIV/AIDS on adult mortality in South Africa. Medical Research Council; Cape Town: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eliott JA, Olver IN. Hope, life, and death: A qualitative analysis of dying cancer patients talk about hope. Death Studies. 2009;33:609–638. doi: 10.1080/07481180903011982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Johnson VA, Trevino M, Duke K, Feliciano L, Jandorf L. A comparison of African American and Latina social networks as indicators for culturally tailoring a breast and cervical cancer education intervention. Cancer. 2007;(2 Suppl):368–377. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garces IC, Scarinci IC, Harrison L. An examination of sociocultural factors associated with health and health care seeking among Latina immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2006;8:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graces IC, Begum R, Subhani S, Kopelman P, Greenhalgh T. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in Bangladeshis: Qualitative study of community, religious and professional perspectives. BMJ. 2008;337:a1931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwelunmor J, Airhihenbuwa CO, Okoror TA, Brown DC, BeLue R. Family systems and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. International Quarterly for Community Health Education. 2007;27:321–325. doi: 10.2190/IQ.27.4.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwelunmor J, Zungu N, Airhihenbuwa CO. Rethinking HIV/AIDS disclosure among women within the context of motherhood in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1393–1399. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S, Webster D, Sparks A, Acker C, Greene-Moton E, Tropiano ET, et al. Using a cultural framework to assess the nutrition influences in relations to birth outcomes among African American women of childbearing age: Application of the PEN-3 theoretical model. Health Promotion Practice. 2009;10(3):349–358. doi: 10.1177/1524839907301406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittikorn N, Street AF, Blackford J. Managing shame and stigma: Case studies of female carers of people with AIDS in Southern Thailand. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:1286–1301. doi: 10.1177/1049732306293992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kylmä J, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Lähdevirta J. Hope, despair and hopelessness in living with HIV/AIDS: A grounded theory study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;33:764–775. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RK. Using a culturally relevant theory to recruit African American men for prostate cancer screening. Health Education Behavior. 2005;32:452–454. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbiti JS. African religions and philosophy. Heinemann Educational Books; London: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus I. Death before dying: Understanding AIDS stigma in the South African Lowveld. Journal of Southern African Studies. 2007;33:845–860. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku KA. African perspectives on death and dying. In: Berger A, et al., editors. Perspectives on death and dying. Charles Press; Philadelphia: 1989. pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros G, Arihihenbuwa CO, Leickness S, Ramalagan S, Brown B. HIV/AIIDS and `othering' in South Africa: The blame goes on. Culture Health and Sexuality. 2006;8:67–77. doi: 10.1080/13691050500391489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ME, Hansen NB, Levy BR, Tate DC, Sikkema KJ. Optimism and coping with loss in bereaved HIV-infected men and women. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24:341–360. [Google Scholar]

- Scarinci IC, Silveira AF, dos Santos DF, Beech BM. Sociocultural factors associated with cigarette smoking among women in Brazilian worksites: A qualitative study. Health Promotion International. 2007;22:146–154. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dam012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg SS. Struggling for meaning: How HIV-positive gay men make sense of AIDS. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1993;24:483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz, Enid, Ogunmefun, Catherine Caring and Contributing: The Role of Older Women in Rural South African Multi-generational Households in the HIV/AIDS Era. World Development. 2007;35(8):1390–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Kochman A, DiFranceisco W, Kelly JA, Hoffmann RG. AIDS-related grief and coping with loss among HIV-positive men and women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:165–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1023086723137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]