Abstract

BACKGROUND

Patients with isolated locoregional recurrences (ILRR) of breast cancer have a high risk of distant metastasis and death from breast cancer. We investigated adjuvant chemotherapy for such patients in a randomised clinical trial.

METHODS

The CALOR trial (clinicaltrials.gov NCT00074152) accrued patients 2003-2010. The 162 patients with resected ILRR were centrally randomised using permuted blocks and stratified by prior chemotherapy, ER/PgR status, and location of ILRR. Eighty-five were allocated to chemotherapy (type selected by the investigator; multidrug for at least four courses recommended) and 77 to no chemotherapy. Patients with oestrogen receptor-positive ILRR received adjuvant endocrine therapy; radiation therapy was mandated for patients with microscopically involved surgical margins, and anti-HER2 therapy was optional. The primary endpoint was disease-free survival (DFS). All analyses were by intention to treat.

FINDINGS

At a median follow up of 4·9 (IQR 3.6,6.0) years we observed 24 DFS events and nine deaths in the chemotherapy group compared with 34 DFS events and 21 deaths in the no chemotherapy group. Five-year DFS was 69% vs. 57%, (hazard ratio for chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy, 0·59; 95% confidence interval 0·35 to 0·99; P=0·046) and five-year overall survival was 88% vs. 76%, (hazard ratio, 0·41; 95% CI, 0·19 to 0·89; P=0·02). Adjuvant chemotherapy was significantly more effective for women with oestrogen receptor-negative disease measured in the recurrence (interaction P=0·04), but analyses of DFS based on the oestrogen receptor status of the primary tumour were not statistically significant (interaction P=0·43). Among the 85 patients who received standard chemotherapy, 12 reported SAEs.

INTERPRETATION

Adjuvant chemotherapy should be recommended for patients with completely resected isolated locoregional recurrences of breast cancer, especially if the recurrence is oestrogen receptor negative.

FUNDING

Public Service Grants U10-CA-37377, -69974, -12027, -69651, and -75362 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Keywords: locoregional recurrence, chemotherapy, breast cancer

Introduction

Local or regional recurrence of breast cancer heralds a poor prognosis following mastectomy or lumpectomy and accompanies or precedes metastasis in a high proportion of cases1. Patients with isolated locoregional recurrences (ILRR), i.e., those without evidence of distant metastasis, harbor a significant risk of developing subsequent distant metastasis with five-year survival probabilities ranging between 45 and 80 percent after LRR1-10 as reviewed by Wapnir et al11.

In a retrospective review of lumpectomy-treated patients in ten National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) clinical trials involving 6468 patients, the five-year distant disease-free survival (DDFS) after an ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence was 67% and 51% for women with node negative and node positive primary breast cancers, respectively9,10. Other locoregional recurrences, such as nodal and chest wall recurrences, resulted in a DDFS of 29% and 19% for node negative and positive cancers, respectively. The corresponding five-year overall survival (OS) after ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence was 77% and 60%, and 35% and 24% after other locoregional recurrences, in patients with node negative and positive disease, respectively. These analyses illustrated the powerful negative prognostic significance of ILRR events and the need for treatments beyond surgical removal of the ILRR.

Adjuvant chemotherapy and endocrine therapies reduce the risk of relapse and death in patients with primary breast cancer12,13. However, few data are available to inform the recommendation of systemic treatment for locoregional recurrence. The Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) prospective randomised trial showed a prolongation in disease-free survival for the use of tamoxifen after locoregional recurrence in hormone-responsive mastectomy-treated patients14. The International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) initiated a trial with collaboration from the Breast International Group (BIG) and NSABP. The CALOR trial (Chemotherapy as Adjuvant for LOcally Recurrent breast cancer; IBCSG 27-02, NSABP B-37, BIG 1-02) was designed as a pragmatic prospective randomised trial to determine whether chemotherapy improves the outcome of patients with ILRR.

Methods

Patients

CALOR accrued patients from August 22, 2003 through January 31, 2010. In January 2005 North American centers began enrollment through NSABP. The trial population is women with histologically proven and completely excised first ILRR after unilateral breast cancer treated by mastectomy or lumpectomy with clear surgical margins. Mastectomy for the ILRR was recommended for patients with prior breast-conserving surgery. Criteria for eligibility included no metastatic disease, no prior malignancy other than the original breast cancer (except in situ of the uterine cervix and nonmelanoma skin cancer), and macroscopically clear margins after surgery for ILRR.

Treatment

Radiotherapy was recommended for all patients but required for those with microscopically involved surgical margins, using at least 50 Gy (lowered to 40 Gy in 2005) with conventional fractionation. After 2006, the administration of radiotherapy prior to randomisation was allowed.

Endocrine therapy was recommended for all patients with ER and/or PgR-positive recurrent tumours. HER2 testing was not required, but in 2004 the study was amended to allow the use of trastuzumab, and, in 2008, other HER2-targeted therapies.

If the patient was randomised to receive chemotherapy, choice of chemotherapy, dose adjustments, and supportive therapies was left to the discretion of the investigators. The protocol recommended at least two cytotoxic drugs for three to six months. Chemotherapy was to start within four weeks of randomisation and within 16 weeks of resection of locoregional recurrence.

Endpoints

Disease-free survival (DFS) was the primary endpoint, defined as the time from randomisation to invasive local, regional or distant recurrence (including invasive in-breast tumour recurrence), appearance of a second primary tumour, or death from any cause. Secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), defined as the time from randomisation to death from any cause, sites of first recurrence after randomisation, incidence of second (non-breast) malignancies, and causes of deaths without relapse of breast cancer.

Randomisation and Masking

Patients were randomly allocated (in a 1:1 ratio) to either chemotherapy or no chemotherapy. Randomisation was done with permuted blocks generated by a congruence algorithm. Randomisation was stratified by prior chemotherapy (yes/no), whether oestrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PgR) was positive in the ILRR according to institutional guidelines (yes/no), and location of ILRR (breast, mastectomy scar/chest wall, or regional lymph nodes).The IBCSG randomisation system used dynamic balancing of treatment assignment within participating center to achieve balance among institutions. After confirming eligibility, participating centre staff accessed the central randomisation system via the internet and entered required information including stratification factors. The randomisation system assigned a patient identification number, treatment group, and date of randomisation via the computer screen with a follow-up email. The IBCSG data management centre developed and maintains the randomisation system. Masking was not done in this trial. The patient, participating centre staff, trial management staff, and others were aware of the assigned treatment.

Study Procedures

At study entry standard staging examinations were performed (x-ray or CT scan of the chest, ultrasound or CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, bone scintigraphy only if alkaline phosphatase is >2x normal or if medically indicated). Follow-up clinical examinations were required every three months during the first two years, every six months years three to five, and yearly thereafter. Annual mammography was required, but other laboratory or imaging studies were left to the discretion of the treating physicians. Only serious adverse events were collected in this pragmatic trial in which a variety of chemotherapy regimens were used. Participating institutions’ ethics committees or Institutional Review Boards approved the trial according to local laws and regulations. All patients gave written informed consent, and the trial was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. The Data and Safety Monitoring Committee reviewed accrual and safety data semi-annually throughout the trial. Data were obtained at the participating centres and transmitted to the IBCSG data management centre in Amherst, New York, USA, via the DataFax or iDataFax system.

Statistical Analysis

The five-year DFS for the group receiving no chemotherapy was originally assumed to be 50%; a total of 347 events was required to detect an improvement in five-year DFS to 60% (hazard ratio (HR)=0·74) with 80% power using a two-sided 0·05 level logrank test with a sample size of 977 patients. Due to a lower than anticipated rate of accrual and to the availability of more active adjuvant agents, in particular taxanes, amendment 3 (2008) decreased the anticipated HR to 0·60 corresponding to an increase of the five-year DFS from 50% to 66%, thereby decreasing the planned sample size to 265 (124 DFS events), allowing for 5% of non-evaluable patients. No results from CALOR were available when this amendment was activated. In November 2009 the independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee recommended the trial close due to low accrual, and CALOR closed on January 31, 2010, with 162 enrolled. In April 2010 the statistical analysis plan was amended to specify the first analysis to occur after a median follow-up period of four years and a minimum follow-up of 2·5 years. The previously planned interim analysis was eliminated and replaced by this single time-driven analysis with statistical significance based on two-sided p-value ≤ 0.05. No results from CALOR, except for the lower than planned enrollment, were available at the time this revised analysis plan was adopted. Unstratified logrank tests were used to compare the two groups15, and Kaplan–Meier estimates were calculated16. Cox proportional-hazards regression was used to adjust for the prespecified prognostic factors location of the ILRR, ER status of the ILRR, interval from the surgery of the primary tumour to the surgery of the ILRR and whether chemotherapy was administered for the primary tumour17. The subgroup analysis according to ER status was clinically motivated and prospectively specified prior to analysis of any data from the current trial. The interaction between the randomised comparison and ER status was also tested in a Cox proportional hazards model. Grambsch and Therneau tests for violations of proportionality were performed for all final models18 and all yielded nonsignificant results. All analyses are by intention to treat, and all P-values reported are two-sided. Data as of October 16, 2012 were used for the efficacy analyses. SAS version 9.2 was used for this analysis. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00074152.

Role of the funding source

The International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) sponsored the trial. There was no pharmaceutical support or specific funding source related to the trial. Other cooperative groups (NSABP, GEICAM, BOOG) provided funding for their participation in the trial. The IBCSG and NSABP were responsible for the design of the study. IBCSG coordinated the collection and management of the data, medical review, and data analysis. The reporting of the results was performed jointly. Members of the trial steering committee (see Section 1 in the appendix, available with the full text of this article at lancet.com) reviewed the manuscript and were responsible for the decision to submit it for publication. SG, SA had access to the raw data. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility to submit for publication.

Results

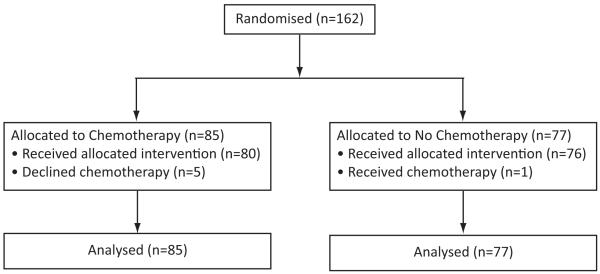

From August 22, 2003 to January 31, 2010 the CALOR trial accrued 162 patients from 54 centers in Europe, South Africa, North and South America and Australia. Eighty-five patients were randomised to receive chemotherapy and 77 to no chemotherapy (Fig. 1). Five patients did not receive assigned chemotherapy. One patient randomised to no chemotherapy requested and received chemotherapy. All 162 randomised patients are included in the intention-to-treat analysis. The patient and disease characteristics, and the treatments received for the ILRR were well-balanced across the two treatment groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Chart Showing the Enrollment and Analysis Population of the CALOR Trial.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Treatment of CALOR Patients According to Randomised Treatment Assignment

| Characteristics | Chemotherapy (N=85) |

No Chemotherapy (N=77) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary surgery – N (%) | ||

| Mastectomy | 33 (39) | 31 (40) |

| Breast conserving surgery | 52 (61) | 46 (60) |

| Prior chemotherapy1 – N (%) | ||

| Yes | 49 (58) | 52 (68) |

| No | 36 (42) | 25 (32) |

| Time from primary to surgery for ILRR | ||

| Median (range) in years | 5·0 (0·3-31·6) | 6·2 (0·4-22·0) |

| Interquartile range (Q1, Q3) | (2·9, 9·5) | (2·9, 11·3) |

| N (%) ≥ 2 years | 72 (85) | 65 (84) |

| Menopausal status at ILRR – N (%) | ||

| Premenopausal | 20 (24) | 14 (18) |

| Postmenopausal | 65 (76) | 63 (82) |

| Median age at ILRR – years (range) | 56 (38-81) | 56 (31-82) |

| Location of ILRR – N (%) | ||

| Breast | 47 (55) | 42 (55) |

| Mastectomy scar/chest wall | 28 (33) | 25 (32) |

| Regional lymph nodes | 10 (12) | 10 (13) |

| ER status of the ILRR – N (%) | ||

| Negative | 29 (34) | 29 (38) |

| Positive | 56 (66) | 48 (62) |

| PgR status of the ILRR – N (%) | ||

| Negative | 39 (46) | 40 (52) |

| Positive | 44 (52) | 35 (45) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 2 (3) |

| ER status of the primary tumour – N (%) | ||

| Negative | 27 (32) | 20 (26) |

| Positive | 49 (58) | 47 (61) |

| Missing | 9 (11) | 10 (13) |

| Treatment for ILRR | ||

| Radiation therapy administered – N (%) | ||

| Yes | 31 (36) | 29 (38) |

| HER2-directed therapies – N (%) | ||

| Yes | 6 (7) | 4 (5) |

| Patients with ER+ or PgR+ ILRR tumours | N=58 | N=52 |

| Any Endocrine Therapy – N (%)2 | 53 (91) | 50 (96) |

| LHRH agonist or oophorectomy | 4 (7) | 10 (19) |

| Fulvestrant | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Tamoxifen | 15 (26) | 15 (29) |

| Aromatase inhibitors | 47 (81) | 41 (79) |

| None | 5 (9) 3 | 2 (4) 4 |

| Chemotherapy Randomised Group | N = 85 | |

| No chemotherapy received – N (%) | 5 (6) | |

| Monochemotherapy – N (%) | 25 (29) | |

| Docetaxel or Paclitaxel | 16 (19) | |

| Capecitabine | 9 (11) | |

| Polychemotherapy – N (%) | 55 (65) | |

| Cyclophosphomide, methotrexate, 5- fluorouracil (CMF) |

2 (2) | |

| Gemcitabine + navelbine | 1 (1) | |

| Anthracycline-based | 38 (45) | |

| Taxane-based | 13 (15) | |

| Anthracycline+taxane-based | 1 (1) |

See Section 2, Table S1 in the appendix for information about the types of adjuvant chemotherapy given for the trial ILRR and as prior chemotherapy.

Patient may have received more than one endocrine therapy.

5 patients did not receive endocrine therapy due to: withdrawal from the study (2); relapse prior to starting endocrine therapy (1); medical decision as ER = 5% (1); PgR+/ER− disease (1).

2 patients did not receive endocrine therapy due to: death prior to starting endocrine therapy (1); PgR+/ER− disease (1).

Abbreviations: ILRR, isolated locoregional recurrence; ER, oestrogen receptor; PgR, progesterone receptor

The median age in both groups was 56 at study entry. The median time interval from primary cancer to ILRR was 5·0 (IQR 2.9,9.5) years for the chemotherapy group and 6·2 (IQR 2.9,11.3) years for the no chemotherapy group; 85% (72/85) of patients in the chemotherapy group and 84% (65/77) of patients in the no chemotherapy group had their ILRR surgery performed at least two years after the diagnosis of their primary cancer. 40% (64/162) of patients had prior mastectomy, and 62% (101/162) of patients received prior adjuvant chemotherapy.

Endocrine Receptor Status and Endocrine Therapy

Overall, 110 patients had hormone receptor-positive ILRR (Table 1). Most (94%; 103/110)) patients with ER or PgR-positive ILRR received adjuvant endocrine therapy. However, two patients with ER and PgR-negative ILRR also received hormonal treatments. There was no statistically significant difference in the use of endocrine therapy between the treatment groups. Of the 143 patients who had ER status reported for the primary tumour, 21/143 (15%) had discordant ER expression in the ILRR: six cases converted from negative to positive and 15 from positive to negative. PgR expression was discordant in 35/137 (26%) of the patients with known PgR expression data. HER2-directed therapies, trastuzumab and lapatinib, were planned in 10/162 (6%) patients.

Adjuvant Chemotherapies for ILRR

Chemotherapies were selected by the treating physicians based on patient and disease characteristics, and prior or ongoing therapies for the primary breast cancer (Table 1). Twenty-nine percent (25/85) of the patients in the chemotherapy group received single cytotoxic agents, with taxanes and capecitabine being the most frequently used. Sixty-five percent (55/85) of patients were treated with combination chemotherapy, predominantly anthracycline-based regimens. The frequency and type of serious adverse events were as anticipated for the therapies used (Table S2 in Section 2 of the appendix).

Disease-Free and Overall Survival

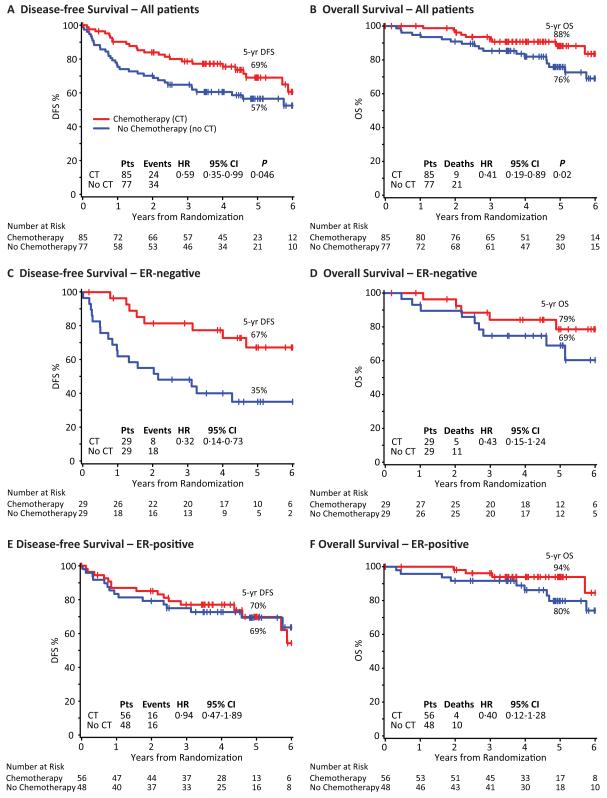

At a median follow-up of 4·9 years (IQR 3.6,6.0), DFS was significantly improved by adjuvant chemotherapy (Fig. 2A). The five-year DFS percent was 69% in the chemotherapy group compared with 57% in the no chemotherapy group with a HR of 0·59 (95% confidence interval (CI), 0·35 to 0·99; P=0·046). There were 24 DFS events in the chemotherapy group compared with 34 in the no chemotherapy group. Chemotherapy reduced both distant and second local failures. The sites of failure after resection of ILRR for the chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy groups were second local/regional: six vs. nine; distant: 15 vs. 22 (comprising soft tissue: nil vs. two; bone: eight vs. five; viscera: seven vs. 15); contralateral breast: one vs. one; second non-breast malignancy: one vs. nil; death without prior cancer event: one vs. nil; and death, cause unknown: nil vs. two. The reduction in the risk of a DFS event remained statistically significant in a multivariable proportional hazards model including factors for ER-status, location of ILRR, prior chemotherapy use, and interval from primary surgery (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Curves of Disease-free Survival and Overall Survival According to Assigned Treatment Group for All Patients (panels A and B), and for ER-negative (panels C and D) and ER-positive (panels E and F) Cohorts. The median follow-up was 4·9 years.

Table 2.

Multivariable Proportional Hazards Regression Model of Disease-free Survival

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| ER of ILRR (ER+/ ER−) | 0·77 (0·43, 1·37) | 0·37 |

| Location of ILRR | ||

| Breast | (reference group) | |

| Mastectomy scar or chest wall | 0·84 (0·45, 1·58) | 0·59 |

| Lymph nodes | 1·18 (0·53, 2·64) | 0·69 |

| Prior chemotherapy (yes/no) | 0·99 (0·57, 1·73) | 0·97 |

| Interval from primary surgery (in years, continuous) |

0·90 (0·85, 0·96) | 0·002 |

| Treatment (chemotherapy/none) | 0·49 (0·29, 0·84) | 0·01 |

Overall survival was also significantly better in the chemotherapy group (Fig. 2B), with nine deaths compared with 21 deaths in the no chemotherapy group. The five-year OS was 88% in the chemotherapy group and 76% in the no chemotherapy group (HR, 0·41; 95% CI, 0·19 to 0·89; P=0·02).

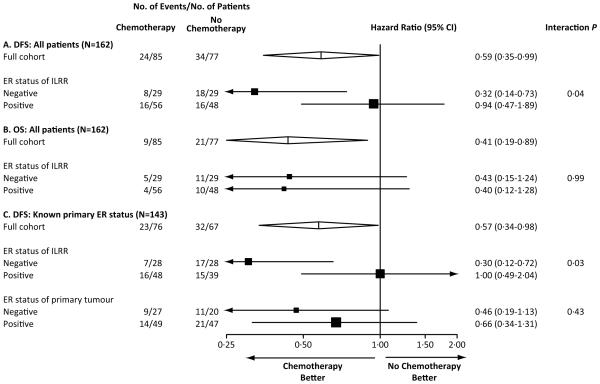

In a pre-specified analysis according to ER status, patients assigned chemotherapy for ER-negative ILRR tumours had a DFS hazard ratio of 0·32 (95% CI, 0·14 to 0·73) favouring chemotherapy (five-year DFS 67% for chemotherapy; 35% for no chemotherapy) (Fig. 2C). In patients with ER-positive ILRR the corresponding DFS hazard ratio was 0·94 (95% CI, 0·47 to 1·89), and the five-year DFS was 70% in the chemotherapy group vs. 69% in the no chemotherapy group (Fig. 2E). For DFS, the interaction between the randomised treatment group and the expression of ER was statistically significant (interaction P=0·04) indicating the effect of chemotherapy in patients with ER-negative ILRR was significantly different from that of the ER-positive cohort (Fig. 3A). Kaplan-Meier curves of OS according to ER status of ILRR are shown in Figs. 2D and 2F, and hazard ratios in Fig. 3B. Confidence intervals are very wide due to the small number of deaths in each of the subpopulations.

Figure 3.

Hazard ratios and confidence intervals for all patients and for patients with known ER status of the primary tumour: Disease-free survival (DFS, A) and overall survival (OS, B) for all 162 patients together and according to the ER status of the isolated locoregional recurrence (ILRR); DFS for 143 patients who had ER status available for both primary tumour and ILRR (C). The size of the boxes is proportional to the number of events. The x-axis is on a log scale.

We further analyzed DFS considering the ER-status of the ILRR tumour and that of the primary tumour for the 143 patients for whom this later status was available (Fig. 3C; Table S3 in Section 2 of the appendix). Consistent with the overall population, a significant interaction was seen with regard to the chemotherapy effect according to ER status of the ILRR (P interaction=0·03). By contrast, the difference in chemotherapy effect according to ER status of the primary tumour was less striking, and the interaction was not statistically significant (interaction P=0·43) (Fig. 3C).

Serious Adverse Events (SAEs)

The protocol stated that adverse events would not be collected on this trial, given that only one treatment arm received chemotherapy, and the regimens were considered “standard” and their toxicities well-known. SAEs were collected for regulatory purposes. Among the 85 patients who received chemotherapy, 12 reported SAEs (appendix Table S2).

Discussion

Recommendations for systemic therapy, particularly chemotherapy, after the occurrence of an ILRR of breast cancer have been the subject of considerable debate. Prospective trials by other cooperative groups investigating adjuvant cytotoxic chemotherapy in this patient population have been unsuccessful and unreported19. The CALOR trial was designed to guide the adjuvant therapy of women experiencing ILRR; the characteristics of the participants with a wide range of intervals between primary surgery and ILRR and with a predominance of ER-positive recurrences was typical for the population under investigation. CALOR was a pragmatic trial in that participating physicians used their professional judgments in selecting cytotoxic drugs, and thus focused more broadly on the study question: the value of systemic chemotherapy. Further, in an attempt to embrace variance in international practice patterns, the sequence of radiation and chemotherapy was not mandated by the trial. The study design required the use of endocrine therapy for hormone responsive cancers based on the reported results of the Swiss trial showing tamoxifen prolonged median disease-free survival from 2·7 to 6·5 years14. Even with this pragmatic design, enrollment to the trial was terminated before reaching the planned sample size due to the slow rate of accrual.

Two reasons may explain the lower than anticipated accrual. One, advances in the local and systemic management of primary breast cancer has lowered the incidence of ILRR in recent years, limiting the pool of eligible patients12,20. Secondly, in spite of the lack of randomised evidence, many oncologists were not genuinely uncertain21 and believed there was sufficient evidence from non-randomised series and randomised trials in other clinical settings to determine whether or not to administer chemotherapy for ILRR22. CALOR did not collect information on the HER2 status of the primary cancer or ILRR; however, the intent to use HER2-directed therapies was recorded from 2004 onward assuming these treatments were surrogate indicators of HER2 overexpression. There is no indication of a differential distribution of HER2-directed therapies; therefore, the observed beneficial effect of chemotherapy is unlikely to be explained by differences in HER2 status. The low number of patients in whom HER2-directed therapies were given makes it likely that investigators were reluctant to randomise patients with HER2-positive ILRR in a trial with a no chemotherapy group.

Participating co-investigators from around the world made reasonable individualized chemotherapy regimen choices for their patients based on prior therapies received and contemporary drug selections. This heterogeneity enhanced the weight of our findings, i.e., the benefit of chemotherapy. The majority of patients with CMF-like or no prior adjuvant chemotherapies received anthracycline-based regimens whereas patients who had prior adjuvant anthracyclines were treated with taxanes for their ILRR; patients whose prior chemotherapy included taxanes were preferentially treated with capecitabine. The individualized selection of chemotherapy by the investigators reduced the absolute risk of a DFS event by 12% at five years after randomisation corresponding to a relative risk reduction of 41%. This benefit in terms of DFS must be weighed against the well-known side effects of chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy was particularly efficacious in patients with ER-negative ILRR reducing the relative risk of further relapses by about two thirds. These findings together with the estimated 59% relative risk reduction in deaths provide strong evidence that isolated breast cancer recurrences are a marker of concurrent occult systemic disease and that a second adjuvant course of chemotherapy should be recommended in this patient population. A beneficial effect of chemotherapy in patients with ER-positive ILRR cannot be excluded as the confidence intervals are wide and the 4.9-year median follow-up may be too short to detect a treatment effect. Thus, any benefit of chemotherapy added to endocrine therapy remains uncertain in the ER-positive ILRR cohort. This uncertainty parallels the situation regarding choice of initial adjuvant therapy of early breast cancer.

There is increasing evidence of the important role of biopsy of metastatic lesions23-26. Our results strongly suggest that tailoring treatment according to the disease characteristics of the metastatic lesion, in this case ILRR, provides a better indication of the possible responsiveness to treatment than does relying on the characteristics of the primary tumour. In particular, the different outcomes based on receipt of chemotherapy according to ER status were more striking when examining cohorts based on ER status in the ILRR than ER status in the primary tumour.

In contrast to some randomised clinical trials in oncology, the planned sample size for the CALOR trial did not suffer from an overly optimistic estimate of treatment effect27. Although small studies may be at risk of ‘false positive’ results28, this is unlikely in the present trial as the results recapitulate evidence regarding the effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapies demonstrated in patients with primary breast cancer12.

In summary, the CALOR trial is the first prospective randomised study supporting the use of chemotherapy in patients with ILRR especially if the recurrence is ER-negative, while it does not exclude its use for patients with ER-positive ILRR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, physicians, nurses, trial coordinators and pathologists who participated in the CALOR trial. We acknowledge the contributions of the participating cooperative groups: NSABP (United States and Canada) enrolled 73 patients, and BIG groups enrolled 89 patients [57 from IBCSG (including 16 from SAKK (Switzerland), 2 from ANZ BCTG (Australia), and 39 from individual IBCSG centers in Hungary, South Africa, and Peru); 20 from GEICAM (Spain); and 12 from BOOG (The Netherlands)]. We thank Dr. Helmut Rauschecker for his support of this international collaboration, and Karolyn Scott for central data management. The authors are grateful for the intellectual contributions that John L. Bryant, PhD, former director of the NSABP Biostatistical Center, made to this study. Dr Bryant died in 2006.

Support: The CALOR trial was supported in part by Public Service Grants U10-CA-37377, -69974, -12027, -69651, and -75362 from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services. The International Breast Cancer Study Group is supported in part by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Australian New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group, Swedish Cancer Society, Cancer Research Switzerland/Oncosuisse, Cancer Association of South Africa, Foundation for Clinical Research of Eastern Switzerland (OSKK). Spanish participation was funded by Grupo Español de Investigación en Cáncer de Mama (GEICAM), and Dutch participation by BOOG, the Dutch Breast Cancer Trialists’ Group.

Footnotes

Contributors Stefan Aebi, Karen N. Price, Richard D. Gelber, Irene Wapnir participated in the design.

Stefan Aebi, Shari Gelber, István Láng, André Robidoux, Miguel Martín, Johan W.R. Nortier, Alexander Paterson, Mothaffar F. Rimawi, José Manuel Baena Cañada, Beat Thürlimann, Elizabeth Murray, Eleftherios P. Mamounas, Charles E. Geyer, Jr., Karen N. Price, Richard D. Gelber, Priya Rastogi, Norman Wolmark, Irene L. Wapnir participated in data collection.

Stefan Aebi, Shari Gelber, Stewart Anderson, Karen N. Price, Richard D. Gelber, Irene Wapnir participated in data analysis. All authors participated in data interpretations, drafting and finalising the report.

Conflicts of interest We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Panel: Research in context Systematic review We searched PubMed for reports from January, 1980, to June, 2013, that contained the terms “Breast Neoplasms/*drug therapy” AND “Neoplasm Recurrence, Local” AND “Randomized Controlled Trials.” This search identified 170 citations, which were manually restricted to clinical trials with more than 50 participants. No trial fulfilling these criteria was identified. One Cochrane review addressing the issue of adjuvant chemotherapy after the resection of locoregional recurrence19, summarized three older and smaller randomised trials with inconclusive results.

Interpretation As far as we are aware, our study is the first sufficiently powered randomised clinical trial to investigate whether adjuvant chemotherapy reduces the risk of further relapse and death in patients with isolated locoregional recurrence of breast cancer. We found that adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to radiation and endocrine therapy prolonged disease-free and overall survival, in particular in patients with oestrogen-receptor negative locoregional relapse. This result challenges the current practice of inconsistent use of chemotherapy and provides evidence in favour of offering adjuvant chemotherapy to women with isolated locoregional relapse of breast cancer.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Clemons M, Danson S, Hamilton T, Goss P. Locoregionally recurrent breast cancer: incidence, risk factors and survival. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:67–82. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haffty BG, Fischer D, Beinfield M, McKhann C. Prognosis following local recurrence in the conservatively treated breast cancer patient. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:293–8. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90774-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abner AL, Recht A, Eberlein T, et al. Prognosis following salvage mastectomy for recurrence in the breast after conservative surgery and radiation therapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:44–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelan T, Clark R, Roberts R, Levine M, Foster G. Ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence postlumpectomy is predictive of subsequent mortality: results from a randomized trial. Investigators of the Ontario Clinical Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;30:11–6. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haffty BG, Reiss M, Beinfield M, Fischer D, Ward B, McKhann C. Ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence as a predictor of distant disease: implications for systemic therapy at the time of local relapse. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:52–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Touboul E, Buffat L, Belkacemi Y, et al. Local recurrences and distant metastases after breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy for early breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman GM, Fowble BL. Local recurrence after mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery and radiation. Oncology (Huntingt) 2000;14:1561–81. discussion 81-2, 82–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwaibold F, Fowble BL, Solin LJ, Schultz DJ, Goodman RL. The results of radiation therapy for isolated local regional recurrence after mastectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:299–310. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90775-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wapnir IL, Anderson SJ, Mamounas EP, et al. Prognosis after ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and locoregional recurrences in five National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project node-positive adjuvant breast cancer trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2028–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson SJ, Wapnir I, Dignam JJ, et al. Prognosis after ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and locoregional recurrences in patients treated by breast-conserving therapy in five National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocols of node-negative breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2466–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wapnir IL, Aebi S, Geyer CE, et al. A randomized clinical trial of adjuvant chemotherapy for radically resected locoregional relapse of breast cancer: IBCSG 27-02, BIG 1-02, and NSABP B-37. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8:287–92. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peto R, Davies C, Godwin J, et al. Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;379:432–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:771–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waeber M, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Dietrich D, et al. Adjuvant therapy after excision and radiation of isolated postmastectomy locoregional breast cancer recurrence: definitive results of a phase III randomized trial (SAKK 23/82) comparing tamoxifen with observation. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1215–21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observation. J Am Statist Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion) J R Stat Soc B (Methodology) 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rauschecker H, Clarke M, Gatzemeier W, Recht A. Systemic therapy for treating locoregional recurrence in women with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002195. CD002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:509–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman B. Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:141–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707163170304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clemons M, Hamilton T, Mansi J, Lockwood G, Goss P. Management of recurrent locoregional breast cancer: oncologist survey. Breast. 2003;12:328–37. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9776(03)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curigliano G, Bagnardi V, Viale G, et al. Should liver metastases of breast cancer be biopsied to improve treatment choice? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2227–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foukakis T, Astrom G, Lindstrom L, Hatschek T, Bergh J. When to order a biopsy to characterise a metastatic relapse in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 10):x349–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoefnagel LD, van de Vijver MJ, van Slooten HJ, et al. Receptor conversion in distant breast cancer metastases. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R75. doi: 10.1186/bcr2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoefnagel LD, Moelans CB, Meijer SL. Prognostic value of estrogen receptor α and progesterone receptor conversion in distant breast cancer metastases. Cancer. 2012 Oct 15;118:4929–35. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gan HK, You B, Pond GR, Chen EX. Assumptions of expected benefits in randomized phase III trials evaluating systemic treatments for cancer. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2012;104:590–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christley RM. Power and error: increased risk of false positive results in underpowered studies. Open Epidemiol J. 2010;3:16–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.