Abstract

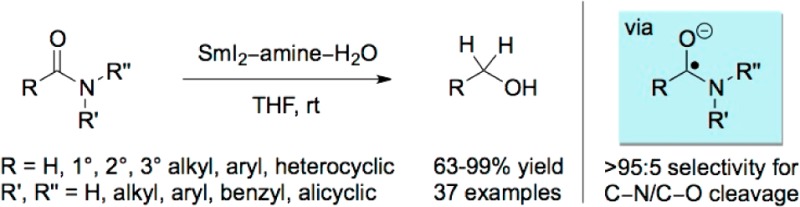

Highly chemoselective direct reduction of primary, secondary, and tertiary amides to alcohols using SmI2/amine/H2O is reported. The reaction proceeds with C–N bond cleavage in the carbinolamine intermediate, shows excellent functional group tolerance, and delivers the alcohol products in very high yields. The expected C–O cleavage products are not formed under the reaction conditions. The observed reactivity is opposite to the electrophilicity of polar carbonyl groups resulting from the nX → π*C=O (X = O, N) conjugation. Mechanistic studies suggest that coordination of Sm to the carbonyl and then to Lewis basic nitrogen in the tetrahedral intermediate facilitate electron transfer and control the selectivity of the C–N/C–O cleavage. Notably, the method provides direct access to acyl-type radicals from unactivated amides under mild electron transfer conditions.

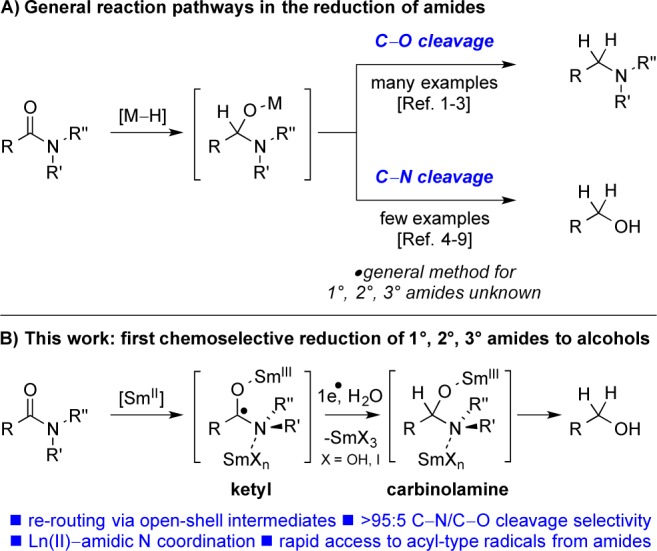

The reduction of carboxylic acid derivatives is among the most important and valuable processes in organic chemistry.1 In particular, the reduction of amides has captured much attention as a practical method for the synthesis of amines from bench-stable amide precursors.2 Over the past decades, many reagents and conditions for this transformation have been reported,3 including recent breakthroughs in highly chemoselective3a and metal-free reductions.3g However, in contrast to the reduction of amides to amines, which typically proceeds via C–O bond cleavage in the tetrahedral intermediate, the development of practical methods for the reduction of amides to alcohols via selective C–N bond scission remains a formidable challenge (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Divergent reaction pathways in the reduction of amides. (b) This work: the first general, highly chemoselective reduction of amides to alcohols.

Very few examples of the chemoselective reduction of amides to alcohols have been reported. Early studies by Brown and co-workers based on typical metal hydride reagents (B–H, Al–H) revealed that the selective C–N cleavage is in principle feasible; however, only one reagent (LiEt3BH) and for only one class of substrates (aromatic N,N-dimethylamides) afforded appreciable C–N cleavage selectivity.4 Subsequently, the groups of Hutchins,5a Singaram,5b,5c and Myers5d,5e studied metal amide–borane complexes for the reduction of sterically unhindered tertiary amides to alcohols. However, this chemistry highlighted a number of limitations, including the low reactivity and/or C–O bond cleavage selectivity for the reduction of primary and secondary amides, inadequate functional group tolerance, and the use of pyrophoric organometallic reagents that decrease the practicality of these methods. Recently, considerable advancements using catalytic hydrogenation have been reported.6−8

Milstein and co-workers developed a reduction of secondary and tertiary amides to alcohols that employs a Ru pincer catalyst at elevated temperatures and high H2 pressures (THF, 110 °C, 10 atm) and proceeds in excellent yields and C–N cleavage selectivity.6 Ikariya7 and Bergens8 reported hydrogenation of activated secondary and tertiary amides/lactams using Ru catalysts at high temperatures and H2 pressures (100 °C, 50 atm). Additionally, Enthaler and co-workers reported a bimetallic Mo complex for the catalytic hydrosilylation of N-aryl tertiary amides with good C–N scission chemoselectivity.9 However, these reactions suffer from limited substrate scope and typically require highly specialized pressure tube and glovebox equipment, which limits their laboratory application. Moreover, primary and secondary amides are difficult substrates because of the presence of free NH bonds. To date, a general method for the reduction of amides to alcohols with high C–N bond cleavage chemoselectivity under mild and practical reaction conditions has not been reported despite the significance of this transformation for the synthesis of fundamental building blocks, such as alcohols, from bench-stable amide precursors.

Herein we report the first general method for the reduction of all types of amides (primary, secondary, and tertiary) to alcohols using the SmI2/amine/H2O reducing system via a single electron transfer mechanism.10 The reaction proceeds with excellent C–N bond cleavage selectivity at room temperature under mild, operationally simple reaction conditions. Notably, this process constitutes the first general method for the synthesis of ketyl-type radicals from unactivated amides.11

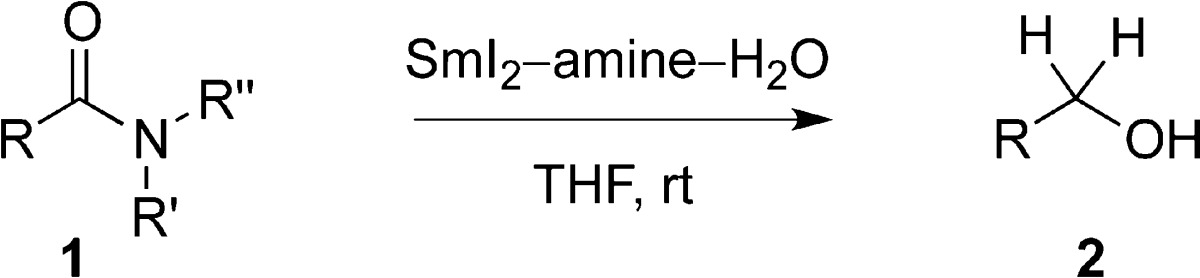

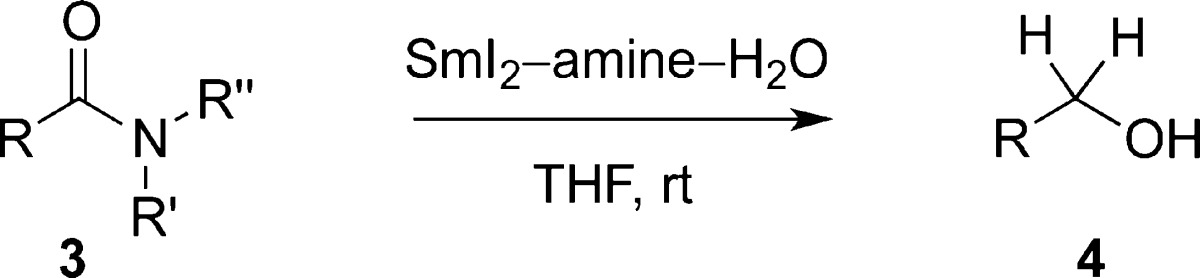

We recently reported the reduction of esters using SmI2/amine/H2O.12 This reagent system efficiently mediates the reduction of esters, lactones, and carboxylic acids under mild conditions via open-shell reaction pathways, which are orthogonal to the traditional closed-shell mechanisms.13 We sought to apply this chemistry to the reduction of unactivated amides.14 We started our investigation by screening the reaction conditions using a cyclic amide substrate, 1-phenylpiperidin-2-one [see the Supporting Information (SI)].15 We were pleased to find that the SmI2/Et3N/H2O system mediates the reduction of 1-phenylpiperidin-2-one in excellent 96% yield with >95:5 C–N/C–O bond cleavage selectivity. Remarkably, these conditions could be readily applied to a range of acyclic amides to afford the corresponding alcohols with excellent C–N/C–O cleavage selectivity and yield (Table 1). Primary, secondary, and tertiary amides afforded the alcohol reduction products in high yields (entries 1–5).

Table 1. Reduction of Amides to Alcohols Using SmI2a.

Conditions: R = Ph(CH2)2, SmI2 (8 equiv), THF, Et3N, H2O, 23 °C. See the SI for full experimental details.

Alicyclic amides (Table 1, entries 6–8), including strained azetidine (entry 6) and aziridine (see the SI) substrates resulted in high selectivity for C–N cleavage. Several amides bearing a directing functionality were subjected to the reaction conditions to determine whether Sm(II) chelation could influence the C–N cleavage selectivity (entries 9–12). In all cases, only alcohol products were formed, suggesting that chelation does not override the inherent reaction pathway.16 We also found that amides featuring substituents known to afford mixtures of C–N/C–O cleavage products with other reagents2a were amenable to the Sm(II) reduction protocol and that useful levels of chemoselectivity were obtained with these substrates (entries 13 and 14). We note, however, that N,N-diisopropylamide was unreactive under our reaction conditions (entry 15).17

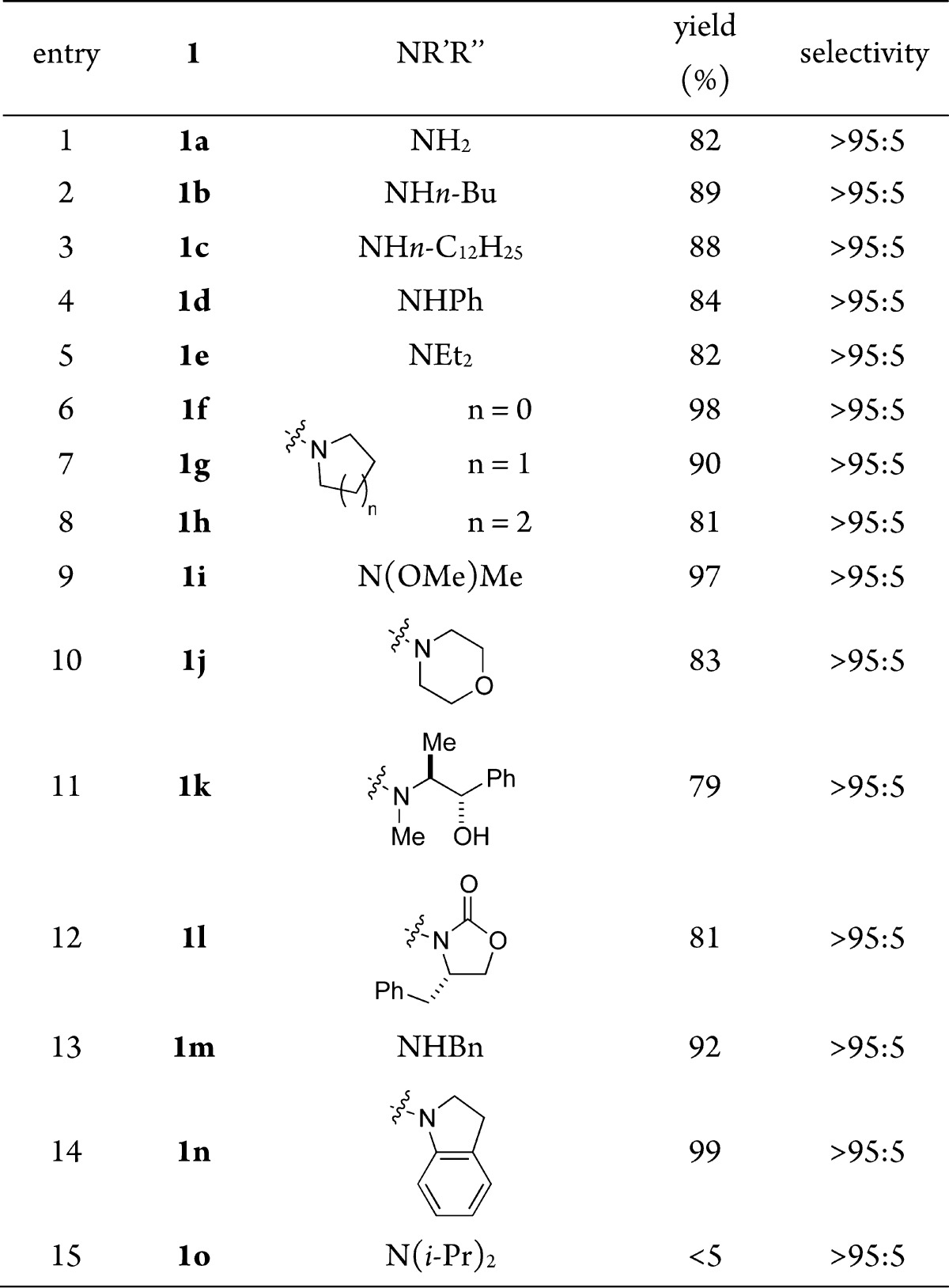

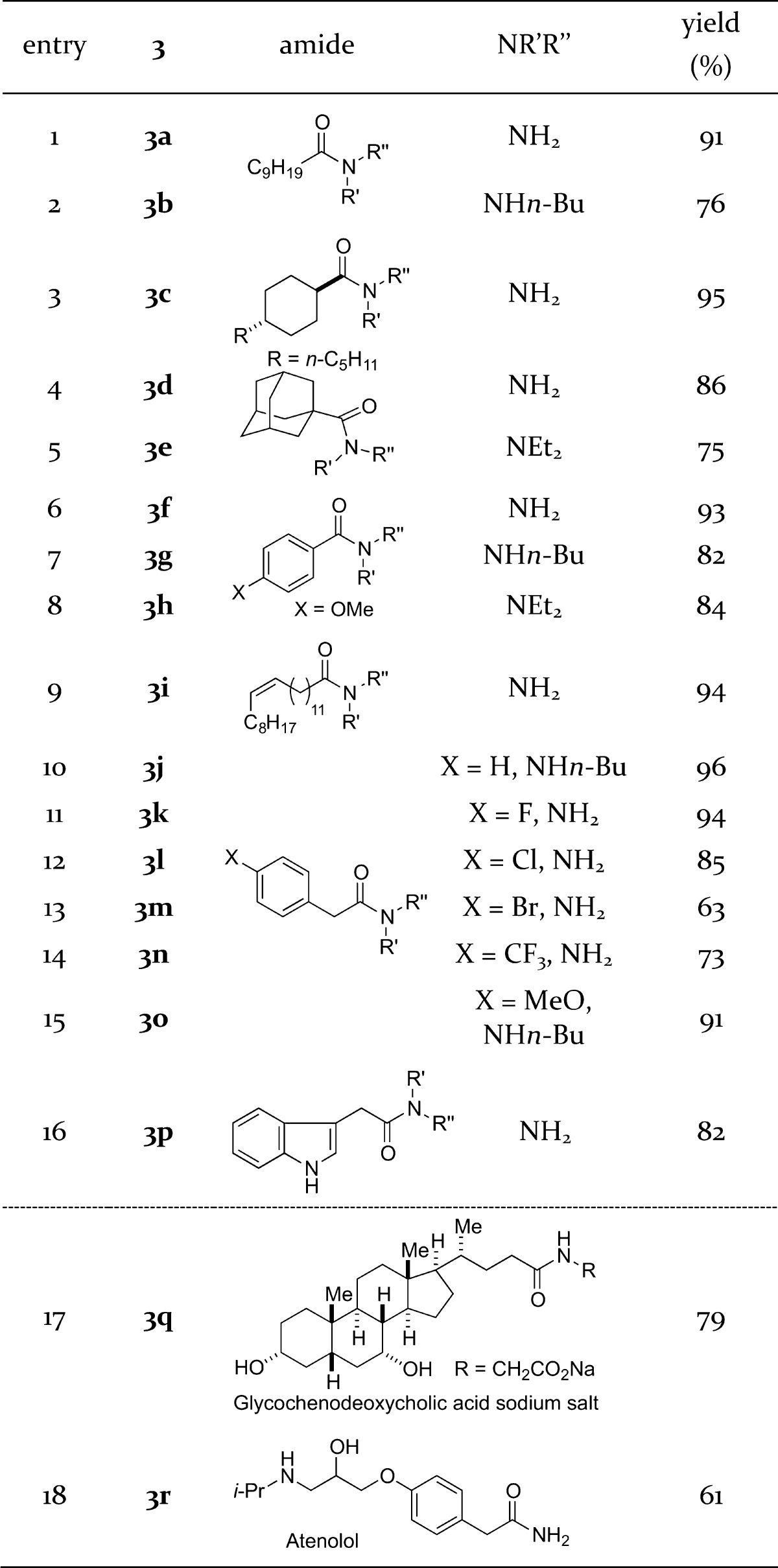

Next, the substrate scope of the reaction was investigated with regard to substitution at the α carbon of the amide with the knowledge that there is an unmet need for the reduction of primary and secondary amides (cf. tertiary amides) to alcohols using existing hydride-mediated3,4 and hydrogenation6−9 methodologies (Table 2). Amides with increasing steric demand at the α carbon were suitable substrates for the reduction (entries 1–5), including a very hindered N,N-diethyl adamantyl amide (entry 5). Aromatic amides could be reduced to the corresponding alcohols with excellent C–N cleavage selectivity (entries 6–8). The method is compatible with a broad range of functional groups, including terminal and internal alkenes (see the SI; isomerization of an internal cis olefin was not observed); aryl fluorides, chlorides, bromides; trifluoromethylphenyl groups; aryl ethers; aromatic rings; and electron-rich heterocycles such as indoles (entries 9–16). In all cases, excellent selectivity for the C–N cleavage was observed. Furthermore, complex biologically active steroid scaffolds and drug molecules bearing unprotected alcohols and amines were subjected directly to the reaction conditions to afford the corresponding alcohols in high yields (entries 17 and 18). In contrast, acidic protons are not tolerated by the recently disclosed highly chemoselective reductions of amides,3 emphasizing the mild reaction conditions and functional group tolerance of Sm(II) systems. Additional studies showed that high selectivity is also possible in the presence of other functional groups (e.g., esters; see the SI for details).

Table 2. Substrate Scope in the Reduction of Amides to Alcohols Using SmI2a.

Conditions: SmI2 (4–8 equiv), THF, Et3N, H2O, 23 °C. See the SI for full experimental details.

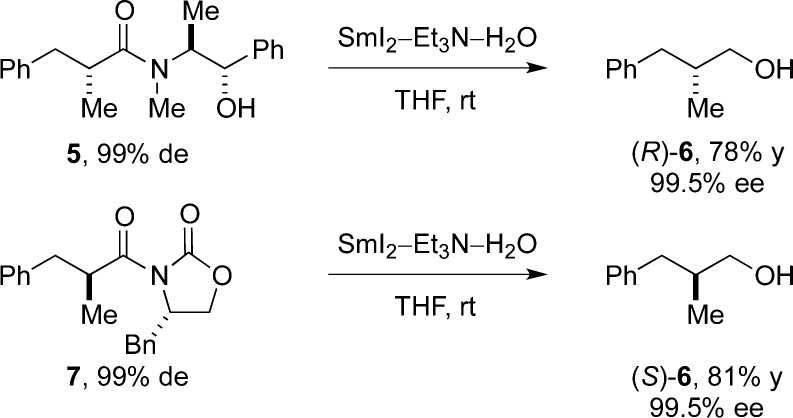

It is particularly noteworthy that the reduction of enantioenriched amides derived from Myers and Evans auxiliaries could be achieved in good yield and selectivity to give the corresponding products in high ee (Scheme 1). The reduction of a diastereoisomer of 5 (see the SI) afforded the corresponding alcohol (S)-6 with high ee. These results demonstrate that amides bearing α-enolizable chiral centers can be readily reduced using this methodology. The recovery of the auxiliaries has not been optimized.

Scheme 1. Reduction of Enantioenriched Amides to Alcohols Using SmI2.

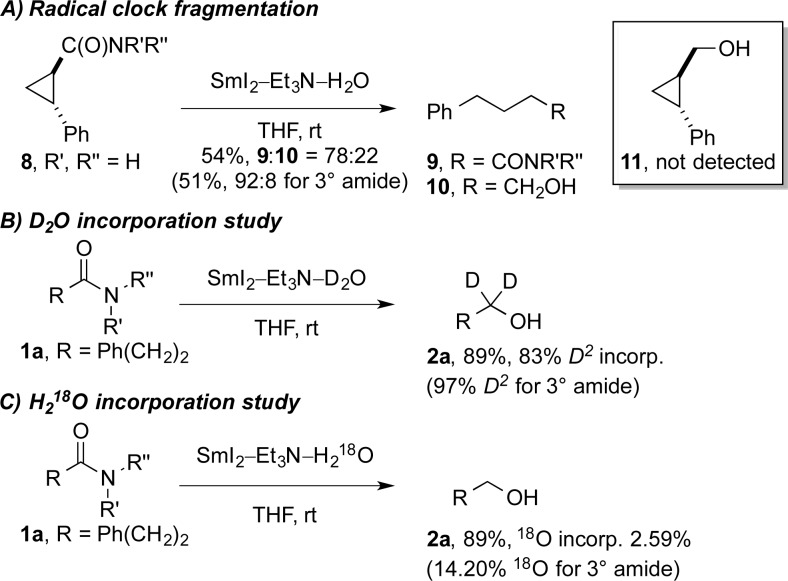

Several studies were conducted to gain insight into the reaction mechanism (see Scheme 2 and the SI): (1) The reduction of trans-cyclopropane radical clocks 8(18) using limiting SmI2 resulted in rapid cyclopropyl ring opening to give acyclic amides 9 and alcohols 10 in the following ratios: 78:22 (primary amide), 85:15 (secondary amide), and 92:8 (tertiary amide). Cyclopropyl carbinol 11 was not detected. In an additional experiment using SmI2/H2O (i.e., without amine), cyclopropane ring opening was observed without further reduction of acyclic amide 9 to alcohol 10. These results suggest that the first electron transfer to the amide carbonyl is reversible and that the rate of the second electron transfer is sensitive to the substitution of the amide nitrogen. (2) The reductions of amides 1a, 1b, and 1e with SmI2/D2O/amine (83% D2 and kH/kD = 1.37 ± 0.1, primary amide; 95% D2 and kH/kD = 1.34 ± 0.1, secondary amide; 97% D2 and kH/kD = 1.32 ± 0.1, tertiary amide) suggested that anions are generated and protonated by H2O in a series of electron transfer steps19 and that proton transfer is not involved in the rate-determining step of the reaction. (3) Control experiments using H218O (2.59% 18O incorporation, primary amide; 4.19%, secondary amide; 14.20%, tertiary amide) showed that amide hydrolysis, or hydrolysis of an iminium intermediate, is not a predominant pathway. (4) Selectivity studies demonstrated the following order of amide reactivity: 1° > 2° > 3°. Moreover, >95:5 selectivity was obtained in the reduction of primary amides over esters and activated over aliphatic secondary amides. (5) A Hammett study performed using a series of 4-substituted 2-phenylacetamides12 showed a large positive ρ value of 0.52 (R2 = 0.98), which can be compared with the ρ value of 0.49 for ionization of phenylacetic acids in H2O at 25 °C. (6) The Taft correlation study, obtained by plotting log(kobs) versus ES for a series of N-alkyl-3-phenylpropanamides showed a large positive slope of 0.92 (R2 = 0.99). The results from the Hammett and Taft studies are consistent with a mechanism involving Sm coordination to the substrate and buildup of partial negative charge on the carbon of the amide carbonyl.13g

Scheme 2. Studies Designed To Probe the Mechanism of the Reduction of Amides to Alcohols using SmI2 (R′, R″ = H; for R′ = H, R″ = n-Bu and R′, R″ = Et, See the SI).

Overall, these results are in agreement with a mechanism involving coordination of the azaphilic Lewis acid Sm20 to nitrogen either before or after the initial electron transfer.21 We postulate that the high chemoselectivity for C–N versus C–O cleavage results from the fact that a protonated hemiaminal is not formed in the reaction. Furthermore, collapse of the carbinolamine intermediate with selective C–N cleavage is likely promoted by the coordination of SmX3 (X = I, OH) to the Lewis basic nitrogen20 (see Figure 1B).

In summary, the first general reduction of primary, secondary, and tertiary amides to alcohols using SmI2/amine/H2O has been developed. The reaction proceeds with high selectivity for C–N bond cleavage under mild and operationally simple reaction conditions. The mechanism involves reversible first electron transfer and electrophilic activation of the amide bond. This protocol demonstrates a broad substrate scope and provides the corresponding alcohols in excellent yields with chemoselectivity orthogonal to that of existing closed-shell processes. We fully expect that this method will be of great interest for the synthesis of functionalized alcohol-containing building blocks. Studies of the application of Sm(II) to chemoselective reductions and reductive cyclizations of functional groups are underway and will be reported shortly.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the EPSRC and GSK for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

† M. Spain and A. J. Eberhart contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Hudlicky M.Reductions in Organic Chemistry; Ellis Horwood Ltd.: Chichester, U.K., 1984. [Google Scholar]; b Seyden-Penne J.Reductions by the Alumino- and Borohydrides in Organic Synthesis; Wiley: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]; c Modern Reduction Methods; Andersson P. G., Munslow I. J., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]; d Addis D.; Das S.; Junge K.; Beller M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Comprehensive Organic Synthesis; Trost B. M., Fleming I., Eds.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, U.K., 1991. [Google Scholar]; b Modern Amination Methods; Ricci A., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]; c Carey J. S.; Laffan D.; Thomson C.; Williams M. T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected recent examples, see:; a Das S.; Addis D.; Zhou S.; Junge K.; Beller M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Das S.; Wendt B.; Möller K.; Junge K.; Beller M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Das S.; Join B.; Junge K.; Beller M. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Das S.; Addis D.; Junge K.; Beller M. Chem.—Eur. J. 2011, 17, 12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zhou S.; Junge K.; Addis D.; Das S.; Beller M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an excellent review, see:; f Das S.; Zhou S.; Addis D.; Junge K.; Enthaler S.; Beller M. Top. Catal. 2010, 53, 979. [Google Scholar]; g Barbe G.; Charette A. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Pelletier G.; Bechara W. S.; Charette A. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an elegant application of chemoselective amide bond activation, see:; i Bechara W. S.; Pelletier G.; Charette A. B. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Reeves J. T.; Tan Z.; Marsini M. A.; Han Z. S.; Xu Y.; Reeves D. C.; Lee H.; Lu B. Z.; Senanayake C. H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 47. [Google Scholar]; k Stein M.; Breit B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Cheng C.; Brookhart M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Park S.; Brookhart M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Hanada S.; Tsutsumi E.; Motoyama Y.; Nagashima H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o Motoyama Y.; Mitsui K.; Ishida T.; Nagashima H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p Sunada Y.; Kawakami H.; Imaoka T.; Motoyama Y.; Nagashima H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; q White J. M.; Tunoori A. R.; Georg G. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11995. [Google Scholar]; r Spletstoser J. T.; White J. M.; Tunoori A. R.; Georg G. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H. C.; Kim S. C. Synthesis 1977, 635. [Google Scholar]

- a Hutchins R. O.; Learn K.; El-Telbany F.; Stercho Y. P. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 2438. [Google Scholar]; b Fisher G. B.; Fuller J. C.; Harrison J.; Alvarez S. G.; Burkhardt E. R.; Goralski C. T.; Singaram B. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 6378. [Google Scholar]; For an excellent overview, see:; c Pasumansky L.; Goralski C. T.; Singaram B. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2006, 10, 959. [Google Scholar]; d Myers A. G.; Yang B. H.; Kopecky D. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 3623. [Google Scholar]; e Myers A. G.; Yang B. H.; Chen H.; McKinstry L.; Kopecky D. J.; Gleason J. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 6496. [Google Scholar]

- a Balaraman E.; Gnanaprakasam B.; Shimon L. J. W.; Milstein D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For other elegant applications of Ru(II) complexes, see:; b Balaraman E.; Gunanathan C.; Zhang J.; Shimon L. J. W.; Milstein D. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Balaraman E.; Ben-David Y.; Milstein D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 11702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ito M.; Koo L. W.; Himizu A.; Kobayashi C.; Sakaguchi A.; Ikariya T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ito M.; Ootsuka T.; Watari R.; Shiibashi A.; Himizu A.; Ikariya T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a review, see:; c Dub P. A.; Ikariya T. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 1718. [Google Scholar]

- John J. M.; Bergens S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krackl S.; Someya C. I.; Enthaler S. Chem.—Eur. J. 2012, 18, 15267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews of metal-mediated radical reactions, see:; a Gansäuer A.; Bluhm H. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Szostak M.; Procter D. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Streuff J. Synthesis 2013, 45, 281. [Google Scholar]; d Radicals in Synthesis I and II; Gansäuer A., Ed.; Topics in Current Chemistry, Vols. 263–264; Springer: Berlin, 2006. [Google Scholar]; For recent reviews of SmI2, see:; e Molander G. A.; Harris C. R. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Krief A.; Laval A. M. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Kagan H. B. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 10351. [Google Scholar]; h Nicolaou K. C.; Ellery S. P.; Chen J. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Szostak M.; Spain M.; Procter D. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 9155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected studies of cyclizations of acyl-type radicals, see:; a Parmar D.; Duffy L. A.; Sadasivam D. V.; Matsubara H.; Bradley P. A.; Flowers R. A. II; Procter D. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Parmar D.; Matsubara H.; Price K.; Spain M.; Procter D. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sautier B.; Lyons S. E.; Webb M. R.; Procter D. J. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Szostak M.; Sautier B.; Spain M.; Behlendorf M.; Procter D. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A study of the mechanism of ester reduction using SmI2/amine/H2O will be reported separately.

- a Szostak M.; Spain M.; Procter D. J. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Szostak M.; Spain M.; Procter D. J. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For other studies of SmI2/amine/H2O, see:; c Cabri W.; Candiani I.; Colombo M.; Franzoi L.; Bedeschi A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 949. [Google Scholar]; d Dahlén A.; Hilmersson G. Chem.—Eur. J. 2003, 9, 1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Dahlén A.; Hilmersson G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Ankner T.; Hilmersson G. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 10856. [Google Scholar]; g Ankner T.; Stålsmeden A. S.; Hilmersson G. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 6867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamochi and Kudo described the reduction of aryl carboxylic acid derivatives using SmI2, but this process is low-yielding and/or limited in scope. See:; a Kamochi Y.; Kudo T. Chem. Lett. 1993, 1495. [Google Scholar]; b Kamochi Y.; Kudo T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1992, 65, 3049. [Google Scholar]; Electrochemical methods for the reduction of amides have been reported. See:; c Benkeser R. A.; Watanabe H.; Mels S. J.; Sabol M. A. J. Org. Chem. 1970, 35, 1210. [Google Scholar]; d Shono T.; Masuda H.; Murase H.; Shimomura M.; Kashimura S. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 1061. [Google Scholar]

- Cyclic carboxylic acid derivatives are more reactive towards Sm(II) because of anomeric stabilization of the radical anion.11a

- Szostak M.; Spain M.; Choquette K. A.; Flowers R. A. II; Procter D. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 15702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Complete recovery of the staring material was observed. In contrast, lithium amidotrihydroborate affords mixtures of C–N/C–O cleavage products with similar substrates.5d This divergent reactivity should prove useful in the selective reduction of this class of amides.

- Newcomb M. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 1151. [Google Scholar]

- a Dahlén A.; Hilmersson G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 3393. [Google Scholar]; b Flowers R. A. II. Synlett 2008, 1427. [Google Scholar]; c Szostak M.; Spain M.; Parmar D.; Procter D. J. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tsuruta H.; Yamaguchi K.; Imamoto T. Chem. Commun. 1999, 1703. [Google Scholar]; b Evans W. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Laurence C.; Gal J.-F.. Lewis Basicity and Affinity Scales: Data and Measurement; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, U.K., 2009. [Google Scholar]; b Cox C.; Lectka T. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.