Abstract

PURPOSE

This study compared the prevalence and patterns of treatment seeking and barriers to alcohol treatment among individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUD) with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders.

METHODS

We used data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions to examine alcohol treatment seeking, treatment settings and providers, perceived unmet need for treatment and barriers to such treatment. Our sample consisted of 5,003 individuals with AUD with a comorbid mood or anxiety disorder and 6,734 individuals with AUD but without mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity.

RESULTS

Overall, the group with mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity was more likely to seek alcohol treatment than the group without such comorbidity (18% vs. 12%, p<0.001). The comorbid group was also more likely to perceive an unmet need for such treatment (8% vs. 3%, p<0.001) and to report a larger number of barriers (2.81 vs. 2.20, p=0.031). Individuals with AUD with comorbid mood or anxiety disorders were more likely than those without to report financial barriers to alcohol treatment (19% vs. 10%, p=0.032).

CONCLUSIONS

Individuals with AUD and comorbid mood or anxiety disorders would likely benefit from the expansion of financial access to alcohol treatments and integration of services envisioned under the Affordable Care Act.

Keywords: substance use services, alcohol use disorders, barriers, perceived need

INTRODUCTION

It is widely recognized that patients in psychiatric and substance disorder treatment settings commonly present with comorbid substance and psychiatric disorders [1–5]. For example, 44% of patients in psychiatric clinics in U.K. urban settings were also diagnosed with a substance use disorder, and 75% of patients in drug disorder services as well as 85% of patients in alcohol disorder services also had a mood or anxiety disorder [6]. The comorbidity is also common in community settings. For example, Grant and her colleagues reported that 20% of individuals with a mood disorder and 18% of individuals with an anxiety disorder in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions also had a substance use disorder [3]. The comorbidity of these disorders makes treatment more challenging due to competing treatment needs of these individuals [7]. In addition, state policies and reimbursement restrictions have historically made it difficult for treatment services for substance and psychiatric disorders to offer integrated care [8, 9]. As a result, many patients with substance disorders and comorbid psychiatric disorders fail to receive the quality care that they need and are at increased risk for relapse and other adverse health outcomes [10–12].

The risk for relapse and adverse outcomes is especially a concern for individuals who misuse alcohol, a substance which is readily available and is the most common substance of abuse in the United States after nicotine [13]. For example, in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication, about 13% of the US adult population were estimated to have a lifetime history of alcohol abuse and over 5% were estimated to have a lifetime history of alcohol dependence [14].

Substance disorder treatments, especially when integrated with psychiatric treatments, have shown promising results in improving the outcomes of patients with comorbid substance and psychiatric disorders [15, 16]. However, relatively little is known about the usual pattern of care and barriers to care for these comorbid conditions in community settings. Past research has found a higher prevalence of treatment seeking among individuals with comorbid disorders [17], perhaps reflecting the greater severity of substance use disorders in these individuals. Past research has also identified a higher prevalence of perceived unmet need for care in individuals with comorbid conditions [18, 19], suggesting that individuals with these comorbid conditions may either face a different set of barriers or a greater number of barriers to treatment.

In this study we examined the prevalence of treatment seeking and types of treatment settings and providers accessed for alcohol problems. We also examined perceived unmet need and barriers to such treatments among individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUD) with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)—a large representative survey of the US general population.

Our study draws on Andersen’s Model of health service utilization [20] to determine the influence of predisposing factors (e.g., socio-demographic and clinical characteristics), enabling factors (e.g., health insurance, financial resources to seek treatment), and need factors (e.g., type of substance disorder), on alcohol use treatment utilization. The study further builds on two previous studies of treatment seeking and barriers to treatment among NESARC participants with alcohol disorders [21, 22]; and extends the findings from these studies by comparing service settings and providers accessed, perceived unmet need for treatment and barriers to treatment in participants with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders.

METHODS

Data Source

The NESARC is a nationally representative survey of the US general population sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Details of the study design and sampling are provided elsewhere [3, 23, 24]. The survey was conducted in two waves 3 years apart. In this report we only used data from wave 1 conducted in 2001–2002. The purpose of the NESARC was to explore the prevalence and correlates of AUD and other substance use and psychiatric disorders in a diverse nationally representative sample of the US population. The NESARC oversampled racial/ethnic minorities and young adults, and weighted the data to adjust for the unequal probabilities of selection and to provide nationally representative estimates. The response rate for NESARC wave 1 was 81%.

Study Sample

The sample for this study included 11,737 NESARC wave 1 participants who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a lifetime AUD (i.e., alcohol abuse and/or dependence) and had responded to questions about seeking alcohol treatment. Of these, 5,003 (42%) also met the criteria for at least one comorbid lifetime DSM-IV mood or anxiety disorder.

Measurements

NESARC used the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) to ascertain diagnoses of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. For this study, lifetime mood and anxiety disorders included major depressive episode, manic episode, dysthymia, hypomanic episode, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder. The AUDADIS-IV is a structured interview that is designed to produce diagnoses of common mental and substance disorders and can be administered by lay interviewers [25–28]. To receive a DSM-IV diagnosis, participants had to endorse the DSM-IV symptom criteria for that disorder as well as affirming distress or social/occupational dysfunction as a result of the disorder. The AUDADIS-IV assesses both lifetime and past-year DSM-IV Axis I and substance use disorders, as well as lifetime history of select personality disorders (antisocial, avoidant, dependent, obsessive compulsive, paranoid, schizoid and histrionic personality disorders). The reliability and validity of AUDADIS-IV has been previously reported [23, 25–31].

This study focused on individuals with lifetime history of alcohol disorders. In addition, alcohol disorder type (abuse only, dependence with/without abuse), and non-alcohol drug use disorders (any, none) were included in the analyses. Non-alcohol drugs included amphetamines, opioids, sedatives, tranquilizers, cocaine, inhalants/solvents, hallucinogens, cannabis, heroin, and other drugs. Lifetime history of personality disorders was dichotomized (any vs. none).

NESARC participants who reported ever having drunk alcohol were asked whether they had “ever sought help” because of drinking. Those who gave an affirmative answer were subsequently asked about their use of a number of treatment settings and providers commonly used in treatment of alcohol disorders. These included: Alcoholics Anonymous, family services, alcohol detoxification clinics, inpatient wards, outpatient clinics, alcoholism rehabilitation services, emergency rooms, halfway houses, crisis centers, employee assistance programs, clergy, health professionals, or other services.

To assess perceived unmet need for treatment, NESARC participants who reported ever having drunk alcohol were asked, “Have you ever thought you should seek help for drinking, but you didn’t go?” Those giving an affirmative response were queried about the reasons for not seeking treatment. Based partly on past research [21, 32], we categorized these barriers into financial, structural, attitudinal, and other.

We also used a number of demographic and clinical characteristics in our analyses, including gender, age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50+ years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, other), annual income (<$20,000, $20,000-$34,999, $35,000-$69,999, $70,000+), urban/rural setting, education (high school diploma or lower, greater than a high school diploma), marital status (married/living with partner, widowed/divorced/separated, never married), and health insurance (any, none).

Statistical Analyses

We compared three mutually exclusive groups of individuals: those who did not seek alcohol treatment and did not perceive a need, those who did not seek treatment and perceived a need for such treatment (perceived unmet need), and those who sought treatment whether or not they also reported perceiving a need for such treatment.

Comparisons of socio-demographic characteristics were conducted in the group of participants with AUD with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders separately. Treatment-seekers as well as those with perceived unmet need were each compared to the non-treatment-seekers as the reference category using separate logistic regression models. Both unadjusted and adjusted analyses were conducted. Adjusted models controlled for gender, age, race/ethnicity, income, urban/rural setting, education, marital status, health insurance, personality disorders, alcohol disorder type, and any non-alcohol drug use disorder.

Next, the use of different alcohol treatment settings and providers were compared among participants with AUD with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders using logistic regression models. Unadjusted and adjusted analyses similar to the ones described above were conducted. Adjusted analyses controlled for the same variables as previously mentioned. These analyses were limited to participants who reported having sought treatment.

Finally, we used logistic regression models to compare the barriers to treatment among participants with AUD with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders. These analyses were limited to participants who reported having perceived an unmet need for alcohol treatment.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic and psychiatric characteristics of participants with alcohol use disorder

Of the 11,737 individuals with AUD in our sample, 58% (N=6,734) met the criteria for AUD without mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity, and 42% (N=5,003) additionally met the DSM-IV criteria for at least one mood or anxiety disorder. The majority of participants with AUD without mood or anxiety comorbidity were male, 40 years old or older, white, had an income greater or equal to $35,000, lived in an urban environment, had a high school diploma or more advanced schooling, were married or lived with a partner, and had health insurance. Individuals with AUD with comorbid mood or anxiety disorders were more likely than those without such comorbidity to be female, to be widowed, divorced or separated, to have no health insurance, to meet the criteria for a personality disorder, for comorbid non-alcohol drug use disorders, and to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence rather than only abuse. Those with comorbid mood or anxiety disorders were also less likely to be age 50 years or older, to be non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, and to have an income greater than $20,000 per year (data not shown).

Prevalence of alcohol use and perceived unmet need for treatment

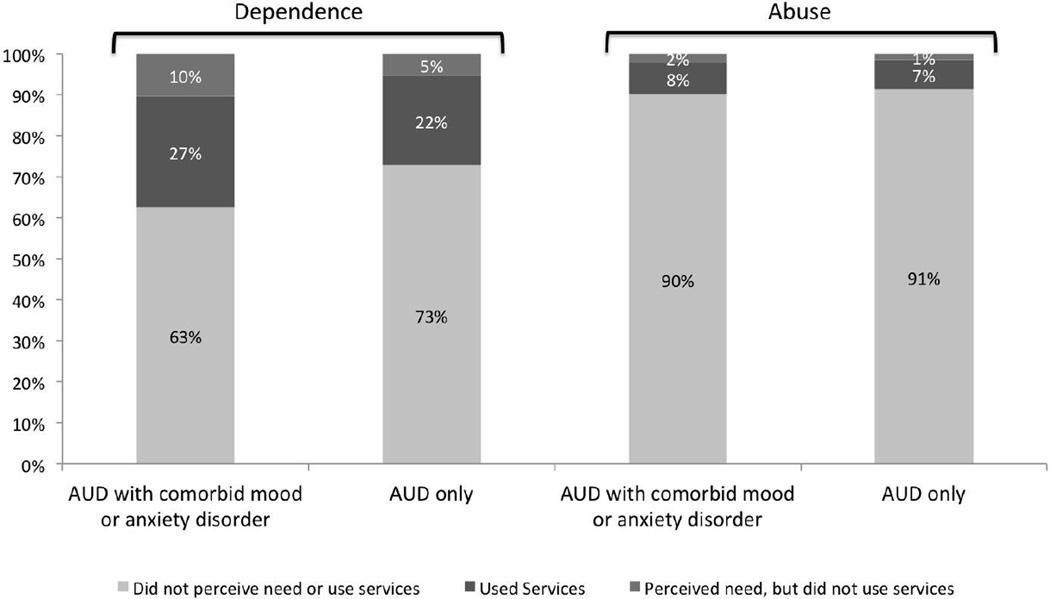

Only 15% (N=1,831) of individuals with AUD reported seeking alcohol treatment, and 4% (N=469) reported perceiving an unmet need for such treatment. Figure 1 presents the patterns of treatment seeking and perceived unmet need for treatment in adults with AUD according to type of AUD and comorbidity. Compared to individuals with AUD without mood or anxiety comorbidity, those with such comorbidity were both more likely to seek alcohol treatment (18% vs. 12%, odd ratio [OR] = 1.61, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.40–1.85, p<0.001) and to report unmet need for such treatment (8% vs. 3%, OR = 2.71, 95% CI = 2.12–3.46, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Service use and perceived unmet need for substance use services among participants with alcohol use disorders (AUD) with or without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders in the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–02

Treatment seeking also varied according to the type of AUD (i.e., abuse vs. dependence). Compared to individuals with alcohol abuse, those with alcohol dependence were more likely to seek alcohol treatment (25% vs. 7%, OR = 4.07, 95% CI = 3.53–4.69, p<0.001), and to perceive an unmet need for such treatment (11% vs. 2%, OR = 6.76, 95% CI = 5.02–9.09, p<0.001).

Correlates of treatment seeking and perceived unmet need for treatment

Analyses were conducted separately among individuals with AUD with and without mood or anxiety comorbidity. Among individuals with AUD without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders, those who perceived an unmet need for alcohol treatment were more likely than those who did not perceive such need or did not seek treatment to be in the 40–49 years age range, to have a personality disorder, and to have alcohol dependence compared to alcohol abuse; but less likely to make $70,000+ per year (Tables 1 and 2). Also, among individuals with AUD without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders, those who sought treatment were less likely to be female, to make $35,000+ annually, and to have more than a high school education, but were more likely to be in the 30+ years age group, to be widowed, divorced, or separated, to have a personality disorder, to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence vs. abuse, and to have a comorbid non-alcohol drug-use disorder (Tables 1 and 2). Similar patterns with minor differences were observed in participants with AUD with comorbid mood or anxiety disorders.

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUD) with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders who sought alcohol treatment or perceived an unmet for such treatment in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–02.

| Lifetime AUD without

comoribid mood or anxiety disorders (N=6,734) |

Lifetime AUD with comorbid

mood and anxiety disorders (N=5,003) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not seek treatment or perceive unmet need (N=5,689) |

Perceived unmet need (N=175) |

Sought treatment (N=870) |

Did not seek treatment or perceive unmet need (N=3,748) |

Perceived unmet need (N=294) |

Sought treatment (N=961) |

|||||||

| Demographic | N | %a | N | %a | N | %a | N | %a | N | %a | N | %a |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 4,061 | 74.1 | 131 | 78.9 | 710 | 84.6 | 1,774 | 51.5 | 158 | 55.8 | 574 | 62.9 |

| Female | 1,628 | 26.0 | 44 | 21.1 | 160 | 15.4*** | 1,974 | 48.5 | 136 | 44.2 | 387 | 37.1*** |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 18–29 | 1,165 | 21.7 | 26 | 17.2 | 130 | 17.4 | 848 | 23.9 | 70 | 25.0 | 154 | 17.6 |

| 30–39 | 1,371 | 24.0 | 45 | 25.0 | 209 | 24.1 | 949 | 24.3 | 70 | 26.2 | 220 | 23.2* |

| 40–49 | 1,286 | 23.5 | 48 | 29.1 | 249 | 29.0** | 928 | 25.8 | 72 | 23.1 | 281 | 30.0** |

| 50+ | 1,867 | 30.8 | 56 | 28.8 | 282 | 29.5 | 1,023 | 26.0 | 82 | 25.8 | 306 | 29.6** |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 3,875 | 80.3 | 104 | 74.8 | 530 | 73.7 | 2,667 | 81.1 | 184 | 75.7 | 659 | 79.2 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 805 | 7.7 | 27 | 8.1 | 155 | 10.7** | 426 | 6.6 | 48 | 7.8 | 117 | 7.1 |

| Hispanic | 819 | 8.1 | 32 | 10.0 | 156 | 10.9* | 502 | 7.2 | 45 | 9.2 | 127 | 7.0 |

| Other | 190 | 3.9 | 12 | 7.2* | 29 | 4.7 | 153 | 5.2 | 17 | 7.2 | 58 | 6.8 |

| Income | ||||||||||||

| <$20,000 | 1,079 | 16.4 | 44 | 20.0 | 249 | 24.3 | 851 | 19.3 | 83 | 23.7 | 358 | 31.8 |

| $20,000-$34,999 | 1,114 | 17.7 | 40 | 20.7 | 221 | 25.5 | 814 | 20.0 | 65 | 18.8 | 204 | 20.5*** |

| $35,000-$69,999 | 1,935 | 33.9 | 54 | 35.9 | 262 | 30.8*** | 1,239 | 33.6 | 86 | 34.3 | 267 | 30.5*** |

| $70,000+ | 1,561 | 32.1 | 37 | 23.6 | 138 | 19.4*** | 844 | 27.2 | 60 | 23.2 | 132 | 17.1*** |

| Urban/Rural | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 4,568 | 78.9 | 146 | 81.1 | 725 | 80.5 | 2,996 | 77.7 | 227 | 76.0 | 758 | 76.4 |

| Rural | 1,121 | 21.2 | 29 | 18.9 | 145 | 19.5 | 752 | 22.3 | 67 | 24.0 | 203 | 23.6 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| ≤High School | 2,231 | 37.7 | 83 | 44.8 | 460 | 54.1 | 1,391 | 36.6 | 143 | 48.9 | 456 | 46.4 |

| Diploma | ||||||||||||

| >High School | 3,458 | 62.3 | 92 | 55.2 | 410 | 45.9*** | 2,357 | 63.4 | 151 | 51.1** | 505 | 53.6*** |

| Diploma | ||||||||||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| Married/Living with Partner | 3,278 | 66.3 | 99 | 66.4 | 416 | 56.6 | 1,858 | 60.0 | 137 | 57.5 | 359 | 46.1 |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 1,067 | 12.4 | 41 | 13.5 | 247 | 21.7*** | 946 | 18.1 | 90 | 22.7 | 360 | 31.1*** |

| Never Married | 1,344 | 21.3 | 35 | 20.1 | 207 | 21.7 | 944 | 21.9 | 67 | 19.7 | 242 | 22.9*** |

| Health Insurance | ||||||||||||

| Anyb | 4,782 | 84.1 | 142 | 84.1 | 658 | 77.0 | 3,067 | 81.7 | 219 | 69.1 | 741 | 78.0 |

| None | 907 | 15.9 | 33 | 15.9 | 212 | 23.0** | 681 | 18.3 | 75 | 30.9*** | 220 | 22.0* |

| Personality Disorders | ||||||||||||

| None | 5,014 | 88.2 | 134 | 76.7 | 709 | 80.7 | 2,338 | 62.6 | 142 | 49.0 | 458 | 45.6 |

| Anyc | 675 | 11.8 | 41 | 23.3** | 161 | 19.3*** | 1,410 | 37.4 | 152 | 51.0** | 503 | 54.4*** |

| Alcohol Disorder Type | ||||||||||||

| Abuse Only | 4,165 | 72.1 | 61 | 35.3 | 376 | 40.8 | 2,125 | 55.7 | 51 | 14.4 | 207 | 20.0 |

| Dependence with/without abuse | 1,524 | 27.9 | 114 | 64.7*** | 494 | 59.3*** | 1,623 | 44.3 | 243 | 85.6*** | 754 | 80.0*** |

| Any Non-Alcohol Drug use Disorder | ||||||||||||

| No | 4,665 | 81.9 | 131 | 74.5 | 556 | 62.1 | 2,622 | 69.4 | 148 | 51.8 | 417 | 40.8 |

| Yes | 1,024 | 18.1 | 44 | 25.6 | 314 | 37.9*** | 1,126 | 30.6 | 146 | 48.2*** | 544 | 59.3*** |

Note: Stars indicate statistical significance levels from unadjusted logistic regression models. The “perceived unmet need” and “sought treatment” groups are both separately compared to the “did not seek treatment or perceive unmet need” group

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Percentages are weighted to be representative of the total U.S. population and account for the complex study design.

Any health insurance includes Medicare, Medicaid, military related, or private insurance.

Any personality disorder includes antisocial, avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, and histrionic personality disorders.

Table 2.

Adjusted comparison of individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUD) with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders who sought alcohol treatment or perceived an unmet need for such treatment in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–02.

| Lifetime AUD without

comoribid mood or anxiety disorders (N=6,734) |

Lifetime AUD with comorbid

mood and anxiety disorders (N=5,003) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived unmet need |

Sought treatment | Perceived unmet need |

Sought treatment | |

| vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | |

| did not perceive unmet need or seek treatment |

did not perceive unmet need or seek treatment |

did not perceive unmet need or use services |

did not perceive unmet need or use services |

|

| Demographic | AORa (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 0.91 (0.54–1.55) | 0.59 (0.46–0.75)*** | 1.02 (0.73–1.42) | 0.72 (0.59–0.89)** |

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 30–39 | 1.76 (0.87–3.57) | 1.76 (1.21–2.57)** | 1.24 (0.82–1.87) | 1.87 (1.36–2.57)*** |

| 40–49 | 2.48 (1.28–4.84)** | 2.25 (1.54–3.30)*** | 1.11 (0.72–1.71) | 2.54 (1.82–3.53)*** |

| 50+ | 2.06 (0.97–4.35) | 2.05 (1.36–3.08)** | 1.86 (1.18–2.91)** | 3.62 (2.53–5.18)*** |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.97 (0.59–1.58) | 1.15 (0.90–1.47) | 1.22 (0.81–1.83) | 0.89 (0.64–1.24) |

| Hispanic | 1.16 (0.70–1.91) | 1.28 (0.95–1.73) | 1.15 (0.72–1.82) | 0.96 (0.65–1.41) |

| Other | 1.78 (0.86–3.66) | 1.03 (0.64–1.68) | 1.48 (0.76–2.89) | 1.25 (0.77–2.02) |

| Income | ||||

| <$20,000 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| $20,000-$34,999 | 0.86 (0.44–1.69) | 1.06 (0.78–1.42) | 0.88 (0.58–1.35) | 0.68 (0.52–0.89)** |

| $35,000-$69,999 | 0.75 (0.42–1.33) | 0.71 (0.55–0.93)* | 1.22 (0.79–1.89) | 0.69 (0.53–0.90)** |

| $70,000+ | 0.52 (0.28–0.97)* | 0.53 (0.38–0.75)*** | 1.29 (0.81–2.04) | 0.56 (0.41–0.76)*** |

| Urban/Rural | ||||

| Urban | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Rural | 0.75 (0.48–1.18) | 0.79 (0.60–1.03) | 1.02 (0.72–1.46) | 1.01 (0.80–1.29) |

| Education | ||||

| ≤High School Diploma | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| >High School Diploma | 0.87 (0.55–1.37) | 0.66 (0.53–0.82)*** | 0.68 (0.47–0.98)* | 0.79 (0.64–0.97)* |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married/Living with Partner | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 0.89 (0.56–1.42) | 1.67 (1.33–2.11)*** | 1.18 (0.81–1.72) | 1.77 (1.38–2.28)*** |

| Never Married | 0.79 (0.46–1.37) | 0.98 (0.71–1.36) | 0.72 (0.48–1.07) | 1.34 (1.02–1.76)* |

| Health Insurance | ||||

| Anyb | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| None | 0.83 (0.47–1.44) | 1.15 (0.88–1.50) | 1.65 (1.16–2.36)** | 0.90 (0.71–1.14) |

| Personality Disorders | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Anyc | 1.85 (1.08–3.18)* | 1.26 (1.00–1.59)* | 1.30 (0.93–1.84) | 1.45 (1.19–1.77)*** |

| Alcohol Disorder Type | ||||

| Abuse Only | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Dependence with/without abuse | 5.03 (3.17–7.97)*** | 3.50 (2.85–4.29)*** | 7.48 (5.02–11.14)*** | 4.66 (3.79–5.74)*** |

| Any Non-Alcohol Drug use Disorder | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.14 (0.67–1.93) | 2.21 (1.77–2.77)*** | 1.65 (1.23–2.22)** | 2.73 (2.26–3.30)*** |

Note: p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Odds ratios are weighted to be representative of the total U.S. population and account for the complex study design. All odds ratios are adjusted for all other variables in the table.

Any health insurance includes Medicare, Medicaid, military related, or private insurance.

Any personality disorder includes antisocial, avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, and histrionic personality disorders.

Treatment settings and providers

Analysis of types of treatment settings and providers accessed was limited to participants who reported seeking any treatment for their alcohol problem. Compared to individuals with AUD without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders, those with AUD with mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity were overall more likely to use most types of settings and providers (Table 3). After adjusting for potential confounders, individuals with AUD and comorbid mood or anxiety disorders reported a higher prevalence of use of inpatient services, outpatient clinics, halfway houses, employee assistance programs, religious counselors, and private physicians or other medical/mental health professionals. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) was the most commonly used type of service in both groups (Table 3). In unadjusted analyses, AA was more commonly used by the comorbid group than the group without mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity. However, this difference did not persist in adjusted analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Alcohol treatment settings and providers accessed by individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUD) with and without mood or anxiety disorders in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–02.

| Lifetime AUD without comorbid mood and anxiety disorders (N=870) |

Lifetime AUD with comorbid mood and anxiety disorders (N=961) |

Bivariate Analysis | Adjusted Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment settings and providers |

N | %a | N | %a | ORa (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) |

| Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics or Cocaine Anonymous meeting, or any 12-step meeting | 641 | 72.6 | 752 | 78.0 | 1.34 (1.02–1.76)* | 1.26 (0.94–1.69) |

| Family services or other social service agency | 151 | 17.5 | 259 | 26.5 | 1.70 (1.27–2.27)** | 1.35 (0.94–1.94) |

| Alcohol or drug detoxification ward or clinic | 245 | 28.7 | 384 | 38.3 | 1.55 (1.18–2.02)** | 1.23 (0.92–1.65) |

| Inpatient ward of a psychiatric or general hospital or community mental health program | 129 | 14.2 | 327 | 33.3 | 3.03 (2.25–4.08)*** | 2.12 (1.52–2.96)*** |

| Outpatient clinic, including outreach programs and day or partial patient programs | 190 | 21.0 | 345 | 35.6 | 2.07 (1.58–2.72)*** | 1.62 (1.23–2.15)** |

| Alcohol or drug rehabilitation program | 351 | 41.0 | 477 | 50.0 | 1.44 (1.15–1.80)** | 1.19 (0.93–1.53) |

| Emergency room for any reason related to your drinking | 172 | 20.4 | 306 | 31.5 | 1.79 (1.36–2.35)*** | 1.30 (0.93–1.81) |

| Halfway house, including therapeutic communities | 46 | 5.2 | 111 | 11.5 | 2.37 (1.51–3.74)*** | 2.11 (1.19–3.77)* |

| Crisis Center for any reason related to your drinking | 14 | 1.7 | 71 | 5.5 | 3.34 (1.61–6.92)** | 2.02 (0.89–4.62) |

| Employee Assistance Program (EAP) | 47 | 5.3 | 90 | 9.8 | 1.94 (1.22–3.07)** | 2.56 (1.41–3.63)** |

| Clergyman, priest, or rabbi for any reason related to your drinking | 82 | 9.1 | 186 | 20.6 | 2.58 (1.82–3.65)*** | 1.81 (1.21–2.72)** |

| Private physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or any other professional | 213 | 25.0 | 472 | 51.2 | 3.14 (2.42–4.08)*** | 2.00 (1.50–2.66)*** |

| Any other agency or professional | 89 | 11.8 | 132 | 13.2 | 1.14 (0.82–1.59) | 1.18 (0.81–1.70) |

Note: p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Percentages and odds ratios are weighted to be representative of the total U.S. population and account for the complex study design. Adjusted odds ratios were adjusted for gender, age, minority status, income, urban/rural, education, marital status, health insurance, personality disorders, alcohol use type, and any drug abuse disorder.

Barriers to alcohol treatment among participants who perceived an unmet need

Reasons for not seeking alcohol treatment in the two groups are presented in Table 4. On average, participants with AUD without mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity experienced a mean of 2.20 barriers, while the comorbid group experienced a mean of 2.81 barriers (β=0.61, SE=0.26, p=0.031). The most common barriers to alcohol treatment were attitudinal barriers for both the AUD with and without comorbid mood or anxiety disorder groups. Individuals with comorbid disorders were significantly more likely to experience financial barriers than individuals without mood or anxiety comorbidity (Table 4). While all other barriers assessed were more commonly reported in the comorbid group, no other barriers were more commonly reported at a statistically significantly level (Table 4).

Table 4.

Barriers to alcohol treatment among individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUD) with and without depression and anxiety disorder comorbidity who perceived an unmet need for alcohol treatment in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–02.

|

Barrier to AUD treatment |

Lifetime AUD Only (N=175) Na (%bc) |

Lifetime AUD with comorbid mood and anxiety disorders (N=294) Na (%bc) |

Bivariate Analysis ORc (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Barriers | 21 (9.8) | 53 (19.2) | 2.18 (1.08–4.41)* |

| Health insurance didn’t cover | 10 | 21 | |

| Couldn’t afford to pay the bill | 16 | 45 | |

| Structural Barriers | 36 (22.0) | 45 (14.4) | 0.60 (0.32–1.13) |

| Didn’t know where to go | 15 | 22 | |

| Didn’t have any way to get there | 5 | 7 | |

| Didn’t have time | 17 | 19 | |

| The hours were inconvenient | 6 | 6 | |

| Can’t speak English very well | 2 | 1 | |

| Couldn’t arrange for child care | 0 | 2 | |

| Had to wait too long to get into a program | 0 | 1 | |

| Attitudinal Barriers (Treatment) | 69 (38.3) | 143 (48.4) | 1.51 (0.92–2.47) |

| Didn’t think anyone could help | 19 | 27 | |

| Was afraid they would put me into the hospital | 6 | 23 | |

| Was afraid of the treatment they would give me | 5 | 23 | |

| Hated answering personal questions | 10 | 36 | |

| Didn’t want to go | 16 | 35 | |

| Stopped drinking on my own | 35 | 78 | |

| Friends or family helped me stop drinking | 5 | 23 | |

| Tried getting help before and it didn’t work | 1 | 0 | |

| Attitudinal Barriers (Disorder) | 108 (69.6) | 211 (72.1) | 1.13 (0.65–1.94) |

| Thought the problem would get better by itself | 55 | 89 | |

| Thought it was something I should be strong enough to handle alone | 62 | 145 | |

| My family thought I should go but I didn’t think it was necessary | 12 | 17 | |

| Wanted to keep drinking or got drunk | 11 | 25 | |

| Didn’t think drinking problem was serious enough | 27 | 64 | |

| Attitudinal Barriers (Stigma) | 28 (17.8) | 66 (22.7) | 1.36 (0.68–2.70) |

| Was too embarrassed to discuss it with anyone | 24 | 54 | |

| Was afraid of what my boss, friends, family, or others would think | 8 | 17 | |

| A member of my family objected | 0 | 2 | |

| Was afraid I would lose my job | 3 | 4 | |

| Other reason | 12 (7.0) | 17 (5.3) | 0.74 (0.24–2.26) |

Note:p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Individuals could report multiple barriers. Therefore, the number of individuals reporting each barrier adds up to more than the total number of individuals reporting barriers in each category.

Percentages are only provided for category totals because of low sample sizes for each individual barrier.

Percentages and odds ratios are weighted to be representative of the total U.S. population and account for the complex study design.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed differences in alcohol treatment-seeking, treatment settings and providers accessed, perceived unmet need for treatment and barriers to alcohol treatment among individuals with AUD with and without a comorbid mood or anxiety disorder. We found that individuals with AUD and a comorbid mood or anxiety disorder were more likely to seek alcohol treatment. This finding is consistent with past research [17, 33] and suggests that individuals with comorbid AUD and common mood or anxiety disorders may experience a more severe form of AUD, a possibility that is borne by the finding of a higher prevalence of alcohol dependence vs. abuse, comorbid non-alcohol drug use disorders and personality disorders in individuals with comorbid AUD and mood or anxiety disorder compared with the AUD group without such comorbidity.

We also found a higher prevalence of perceived unmet need for treatment in the AUD with comorbid mood or anxiety disorder group. This finding is also consistent with past research and suggests that while experiencing a greater level of need for alcohol treatment, individuals with comorbid AUD and mood or anxiety disorders also experience a greater number or different types of barriers. A finding of a specific profile of barriers to treatment among individuals with AUD with mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity would have implications for design of services and policies to improve access to alcohol treatment in the large group of individuals with comorbid disorders. Indeed, socio-demographic differences between the AUD groups with and without mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity suggest possible differences in barriers. Individuals without mood or anxiety comorbidity were more likely to be male, belong to the white racial/ethnic group, have a higher education, earn $35,000 or more annually, live in an urban setting and have health insurance. In contrast, individuals with AUD with mood or anxiety comorbidity were more likely to be female, earn less than $20,000 and to have other psychiatric and substance disorder comorbidity. These differences in predisposing (gender, race/ethnicity), enabling (insurance, income, urbanicity), and need factors (type of AUD, other comorbid conditions) suggest different patterns of treatment seeking behavior and different barriers to treatment [20]. Individuals with lower income and no health insurance as well as those who live in rural areas face a greater number of barriers to substance disorder services and other health services. Indeed, we found a larger number of barriers among the comorbid group. However, the association of comorbidity with perceived unmet need persisted in the adjusted model controlling for socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. It is possible that the persisting difference among the AUD groups with and without comorbidity is due to unmeasured differences between the two groups in severity or impairment in functioning.

Despite the marked difference in the level of perceived unmet need between the individuals with AUD with and without mood or anxiety comorbidity, and the differences in the number of barriers, the types of barriers reported by the two groups were for the most part similar, with the exception of financial barriers which were more commonly reported by the comorbid group. This difference is likely at least partly attributable to the larger percentage of participants without insurance in the comorbid group. In total, 30.9% of individuals with AUD and comorbid mood or anxiety disorders who reported a perceived unmet need for substance disorder treatment indicated that they did not have health insurance, compared to 15.9% of those without such comorbidity (Table 1). Improved financial access to AUD treatments through expansion of Medicaid insurance as envisioned in the Affordable Care Act and expansion of coverage to substance disorder treatments through the Mental Health Parity Act would likely reduce the level of unmet need for treatment due to financial barriers among participants with AUD and comorbid mood or anxiety disorders.

Past research has suggested that individuals with substance disorders are much more likely to receive treatment in mental health treatment settings than in substance disorder treatment settings [34], pointing to potential benefits of integrating substance disorder treatments in mental health care services. The results from the present study further highlight the need for integration of these services. Over the years, a number of states have initiated such integrated programs [35–37]. However, there are financial, structural and attitudinal barriers to integration of these services [8]. Successful integration of mental health and substance disorder services as well as general medical services for patients with comorbid conditions remains a challenge for the upcoming reform of the health care system in the US.

The findings from this study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, data gathered from the NESARC are based on self-reports by participants and therefore subject to recall and social desirability bias. Second, the small sample size of participants who reported barriers to treatment may have reduced the power to detect meaningful differences between the AUD groups with and without mood or anxiety disorder comorbidity. More targeted studies about barriers to treatment among individuals with AUD are warranted to fully understand differences in barriers faced by those with comorbidity and those without. Third, the list of barriers probed was limited and some barriers that may be especially important for individuals with comorbid disorders were likely missing. For example, many individuals with AUD with comorbid mood or anxiety disorders might have decided not to use services because the types of services that they desired or found helpful (e.g., integrated mental health and AUD services) were not available to them.

Despite these limitations, this study extends findings from previous studies [21, 22] on treatment-seeking and treatment barriers in substance disorders and furthers our knowledge of the use of alcohol treatments among individuals with comorbid alcohol and psychiatric disorders. This large subgroup of individuals with AUD reports a greater level of unmet need for alcohol treatment, faces a greater number of barriers to such treatment, and is especially faced with financial barriers to needed care. These individuals likely stand to benefit most from integration of psychiatric and substance disorder services [15, 34]. As the health care system of the country evolves, it would be important to continue monitoring treatment use and treatment barriers in this group of individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported in part by funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA030460-02) and from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA016346).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Mojtabai has received consulting fees from Lundbeck pharmaceuticals in the past 3 years. Other authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bukstein OG, Brent DA, Kaminer Y. Comorbidity of substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:1131–1141. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.9.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addict Behav. 1998;23:893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807– 816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, et al. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:71–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130077015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rounsaville BJ, Anton SF, Carroll K, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:43–51. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250045005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver T, Madden P, Charles V, et al. Comorbidity of substance misuse and mental illness in community mental health and substance misuse services. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:304–313. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murthy P, Chand P. Treatment of dual diagnosis disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:194–200. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328351a3e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, et al. Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:469–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank RG, McGuire TG, Regier DA, et al. Paying for mental health and substance abuse care. Health Aff (Millwood) 1994;13:337–342. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.13.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradizza CM, Stasiewicz PR, Paas ND. Relapse to alcohol and drug use among individuals diagnosed with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:162–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tate SR, Brown SA, Unrod M, Ramo DE. Context of relapse for substance-dependent adults with and without comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1707–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grella CE, Hser YI, Joshi V, Rounds-Bryant J. Drug treatment outcomes for adolescents with comorbid mental and substance use disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:384–392. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watts RK, Rabow J. Alcohol availability and alcohol-related problems in 213 California cities. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1983;7:47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1983.tb05410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2008:1–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnam MA, Watkins KE. Substance abuse with mental disorders: specialized public systems and integrated care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:648–658. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu LT, Kouzis AC, Leaf PJ. Influence of comorbid alcohol and psychiatric disorders on utilization of mental health services in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1230–1236. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L-Y, Crum RM, Martins SS, et al. Service Use and Barriers to Mental Health Care Among Adults With Major Depression and Comorbid Substance Dependence. Psychiatr Serv. 2013 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oleski J, Mota N, Cox BJ, Sareen J. Perceived need for care, help seeking, and perceived barriers to care for alcohol use disorders in a national sample. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:1223–1231. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.12.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grella CE, Karno MP, Warda US, et al. Perceptions of need and help received for substance dependence in a national probability survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1068–1074. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.8.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, et al. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, et al. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pull CB, Saunders JB, Mavreas V, et al. Concordance between ICD-10 alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by the AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN: results of a cross-national study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, et al. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:948–958. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al. Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Co-occurrence of DSM-IV personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F. Treatment-seeking for depression by black and white Americans. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burns L, Teesson M. Alcohol use disorders comorbid with anxiety, depression and drug use disorders. Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well Being. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:299–307. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mojtabai R. Use of specialty substance abuse and mental health services in adults with substance use disorders in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, et al. Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995;14:173–184. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drake RE, Antosca LM, Noordsy DL, et al. New Hampshire's specialized services for the dually diagnosed. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 1991:57–67. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319915007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridgely MS, Lambert D, Goodman A, et al. Interagency collaboration in services for people with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:236–238. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]