Abstract

Structure-guided design was used to generate a series of noncovalent inhibitors with nanomolar potency against the papain-like protease (PLpro) from the SARS coronavirus (CoV). A number of inhibitors exhibit antiviral activity against SARS-CoV infected Vero E6 cells and broadened specificity toward the homologous PLP2 enzyme from the human coronavirus NL63. Selectivity and cytotoxicity studies established a more than 100-fold preference for the coronaviral enzyme over homologous human deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), and no significant cytotoxicity in Vero E6 and HEK293 cell lines is observed. X-ray structural analyses of inhibitor-bound crystal structures revealed subtle differences between binding modes of the initial benzodioxolane lead (15g) and the most potent analogues 3k and 3j, featuring a monofluoro substitution at para and meta positions of the benzyl ring, respectively. Finally, the less lipophilic bis(amide) 3e and methoxypyridine 5c exhibit significantly improved metabolic stability and are viable candidates for advancing to in vivo studies.

Introduction

More than 10 years after the pandemic caused by the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) coronavirus (CoV), no anticoronaviral regimens have been developed for the treatment of SARS-CoV or any other human coronaviruses (HCoV) infection. SARS-CoV was established as the causative agent of the fatal global outbreak of respiratory disease in humans during 2002–2003 that resulted in a case-fatality rate (CFR) of 11%.1 In October 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) added SARS-CoV to the select agents list of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Among many aspects that make SARS-CoV a potential threat to the human population, the lack of effective vaccines or anticoronaviral drugs had a significant impact in its classification as a select agent. However, even with the most extensive preventive measures, the reemergence of SARS-CoV or other virulent human coronaviruses poses a continuing threat. A powerful reminder of this, as well as of the fatal repercussions of the interspecies transmission potential of CoVs, was brought to the forefront in September 2012 by the emergence of a new SARS-like respiratory virus (previously termed HCoV-EMC, now designated Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, MERS-CoV).2,3 As in the case of SARS-CoV, the MERS-CoV is likely of zoonotic origin4 and closely related to bat coronaviruses from the Betacoronavirus genus (group 2).5 Reminiscent of the initial stages of SARS-CoV pandemic, global travel has contributed to the spread of MERS coronavirus, with a total of 178 laboratory-confirmed cases and a CFR of 43%.6 The infected individuals display SARS-like symptoms, including a severe respiratory infection (SRI), and sometimes exhibit an acute renal failure which is a unique signature of MERS infection.2b,7 Today, a total of 6 human coronaviruses are known, of which SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are recognized as highly pathogenic with the potential for human-to-human transmission.8 Without an efficacious antiviral agent or vaccine, the prevention of current and emerging coronaviruses continues to rely strongly on public health measures to contain outbreaks. Therefore, research toward the development of anticoronaviral drugs continues to be of paramount importance.

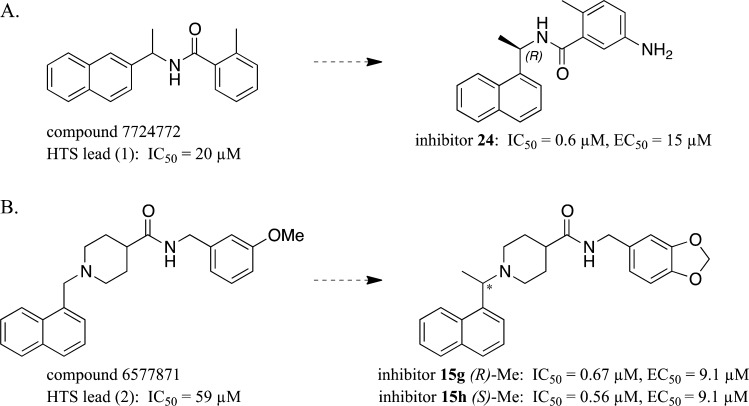

The development of anticoronaviral drugs is challenging. Although a number of coronaviral proteins have been identified as potential drug targets,9 further development of drug candidates has been compromised by the general lack of antiviral data and biological evaluations, which can be done only in BSL-3 facilities with select agent certification for laboratories in the U.S. Two of the most promising drug targets are the SARS-CoV-encoded cysteine proteases, 3CLpro (chymotrypsin-like protease) and PLpro (papain-like protease). PLpro, in addition to playing an essential role during virus replication, is proposed to be a key enzyme in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV. The well-established roles of PLpro enzymatic activities include processing of the viral polyprotein,10 deubiquitination11(the removal of ubiquitin), and deISGylation12 (the removal of ISG15) from host-cell proteins. These last two enzymatic activities result in the antagonism of the host antiviral innate immune response.13 The SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitors (compounds 24(14) and 15g,h15), previously identified in our lab via high-throughput screening (HTS), have low micromolar inhibitory potency with minimal associated cytotoxicity in SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells and are therefore viable leads for the development of drug candidates (Figure 1). Detailed reports of the synthesis and biological evaluation of inhibitors 24(14) and 15g(15) and their X-ray structures in complex with SARS-CoV PLpro have been previously described.

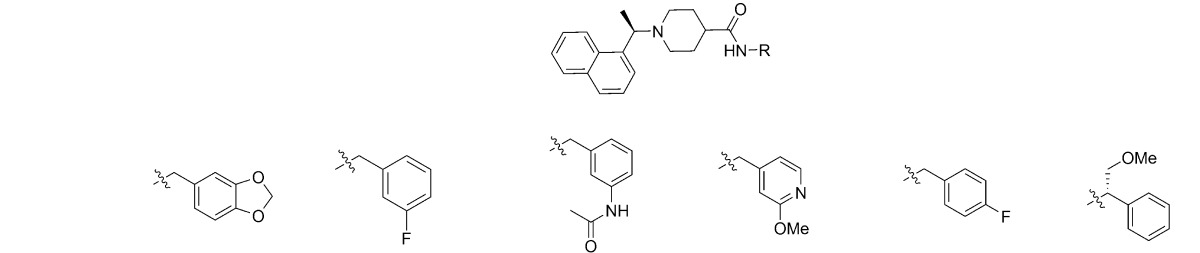

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of previously characterized SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitors: (A) hit (1) from a primary HTS from which lead 24 was developed; (B) hit (2) from a primary HTS from which 15g and 15h were developed. The chiral center for the nearly equipotent isomers derived from hit 2 is indicated with an asterisk.

Compounds 24, 15h, and 15g share a number of chemical and structural features (Figure 1), including the presence of a naphthyl group adjacent to a stereogenic center containing a methyl group and a nitrogen-centered hydrogen bond (H-bond) donor (at a physiological pH). In addition, these leads share carboxamide linkers of opposite orientation to differentially substituted benzenoid groups. Structure–activity relationships (SARs) have shown that in both inhibitor subtypes the naphthyl ring is optimally substituted at C-1 and the presence of the methyl group at the aforementioned stereogenic center is important for potency.14,15 Interestingly, SARS-CoV PLpro exhibited significant stereopreference for the (R)-enantiomer of 24 (IC50 = 0.6 μM, EC50 = 15 μM),14 while minimal stereochemical selectivity was observed between enantiomers (R)-15g and (S)-15h (IC50 values of 0.67 and 0.56 μM, respectively; EC50 of 9.1 μM for both).15

The structural bases for the high binding affinity of inhibitors 24 and 15g,h are also quite similar. The X-ray crystal structures of PLpro–24 and PLpro–15g complexes revealed several hydrophobic interactions resultant of the highly hydrophobic naphthyl ring and few hydrogen bonds.13a,14 In addition, significant conformational changes within the active site are prominent between the apo16 and inhibitor-bound structures.14,15 Specifically, there is a highly mobile β-turn/loop (Gly267-Gly272) adjacent to the active site that closes upon inhibitor binding, thereby changing the orientation of the enzyme’s backbone to allow for H-bonding with the inhibitor’s core. However, relative to the conformation adopted with the smaller inhibitor 24, compound 15g requires a different and slightly more opened conformation to accommodate the longer piperidine-4-carboxamide scaffold and the bulkier 1,3-benzodioxole ring.

Because the antiviral potencies of these SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitors are likely not yet sufficient to make them therapeutically viable, further optimization of their inhibitory potencies, as well as physicochemical properties, is necessary. Toward this goal, we utilized our previous SAR analysis and the X-ray structure of compound 15g in complex with SARS-CoV PLpro to develop a second generation of PLpro inhibitors. Here, we disclose SAR of a new series of potent SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitors, their selectivity, antiviral efficacy, biological evaluation, and a detailed report of the molecular interactions between SARS-CoV PLpro and inhibitors 3k and 3j aided by X-ray crystallographic studies. Compound 3k was established to be the most potent SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitor identified thus far in vitro. Furthermore, this compound displayed effective perturbation of SARS-CoV replication in Vero E6 cells while displaying low cytotoxicity and high selectivity for SARS-CoV PLpro over human homologue enzymes. The improved resolution of the SARS-CoV PLpro–3k and PLpro–3j X-ray structures revealed novel factors accounting for the observed high binding affinities of the piperidine-containing compounds and the previously elusive molecular contributions of the benzyl substituent of the carboxamide. Therefore, our data highlight 3k, as well as two slightly less potent but more metabolically stable analogues 3e and 5c, as good candidates for advancing to preclinical evaluations. In addition, we demonstrate the effective inhibition of PLP2 from HCoV-NL63, a potentially fatal pathogen in children and elderly, by compound 3k and related analogues. Importantly, these compounds may also present an opportunity for the development of broader-spectrum antiviral drugs against infections caused by both SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

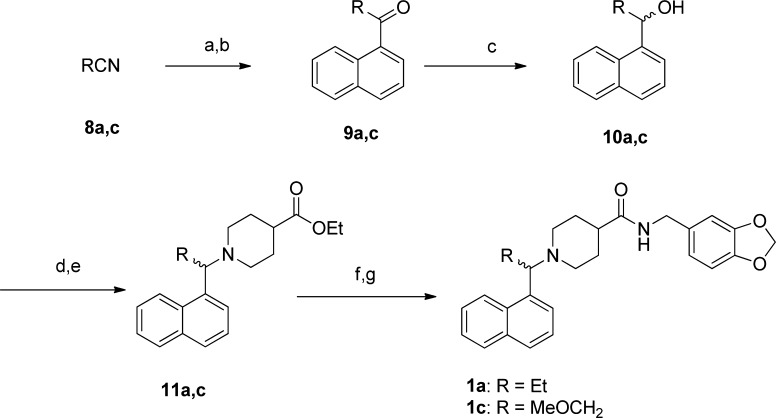

The preparation of analogues 1a–d bearing substitution off the α-methyl group is summarized in Schemes 1–3.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of α-Substituted Naphthyl Analogues.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 1-naphthyl-MgBr, ether, rt; (b) Aq HCl; (c) LAH, THF, rt; (d) Ms2O, DIEA, DCM, 0 °C; (e) ethyl isonipecotate, rt; (f) aq NaOH, EtOH, THF; (g) piperonylamine, EDCI, HOBt, DIEA, rt.

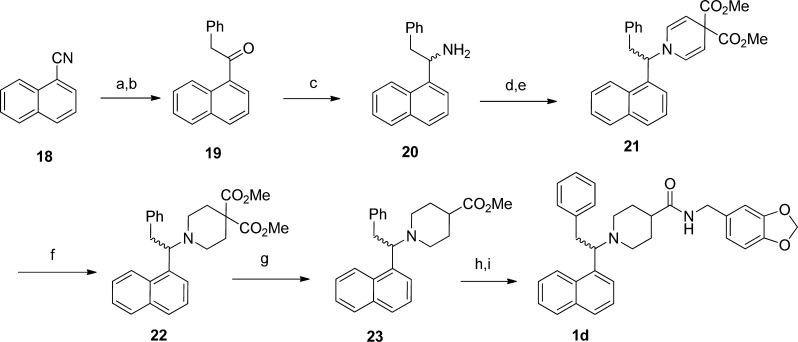

Scheme 3. Synthesis of α-Phenylmethyl Analogue 1d.

Reagents and conditions: (a) BnMgCl, ether, rt; (b) 1 M HCl, ether, 90 °C; (c) CH3ONH2, pyridine, rt; then BH3–THF, 80 °C;18 (d) dimethyl 2,2-bis((1,3-dioxolan-2-yl)methyl)malonate, HCl/THF; (e) 20, rt, 20 h; (f) H2, Pd/C, 40 psi, rt; (g) NaCN, DMF, 145 °C; (h) 1 M aq NaOH, EtOH, 60 °C; (i) piperonylamine, EDCI, HOBt, DIEA, rt.

The appropriate nitriles 8a,c were treated with 1-naphthyl Grignard reagent, and the intermediary imines were hydrolyzed to the ketones 9a,c under acidic conditions (Scheme 1).17 The ketones were then reduced by the action of LAH to the alcohols 10a,c, which were mesylated and displaced by treatment with ethyl isonipecotate to provide the amino esters 11a,c. Saponification to the carboxylic acids was followed by coupling with piperonylamine to give final racemic analogues 1a,c.

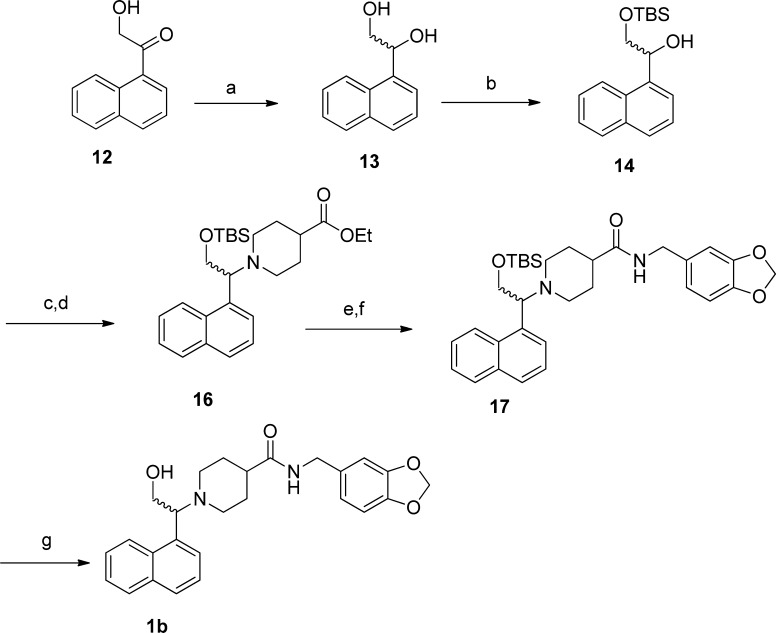

A similar displacement strategy was employed to obtain hydroxyl analogue 1b (Scheme 2). Hydroxy ketone 12(18) was reduced with LAH to the diol 13, and the primary alcohol was selectively protected as the tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS) ether to give 14. The free secondary alcohol was mesylated and displaced by ethyl isonipecotate, and the resulting amino ester 16 was hydrolyzed to the corresponding acid and coupled with piperonylamine to provide the TBS-protected compound 17. The silyl ether was removed with CsF to afford the desired hydroxy analogue 1b.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of α-Hydroxymethyl Analogue 1b.

Reagents and conditions: (a) LAH, THF, rt; (b) TBSCl, imidazole, ether, rt; (c) Ms2O, DIEA, DCM, rt; (d) ethyl isonipecotate, rt; (e) aq NaOH, EtOH, 40 °C; (f) piperonylamine, EDCI, HOBt, DIEA, rt; (g) CsF, aq ACN, rt.

The displacement route used in Schemes 1 and 2 was not successful with the more hindered phenyl analogue 1d, so we had to employ the lengthier approach previously reported by Ghosh et al. (Scheme 3).15 1-Naphthonitrile 18 was treated with benzylmagnesium chloride, and the resulting imine was hydrolyzed under acidic conditions to the ketone 19. Reductive amination as previously described19 provided amine 20. This amine was then condensed with the bis-aldehyde derived from dimethyl 2,2-bis((1,3-dioxolan-2-yl)methyl)malonate to give the dihydropyridine dimethyl ester 21, which was readily reduced to the piperidine 22 by heterogeneous hydrogenation. The diester was converted into the monoester 23 by the Krapcho method and was subsequently hydrolyzed to the acid and coupled with piperonylamine to give the desired analogue 1d.

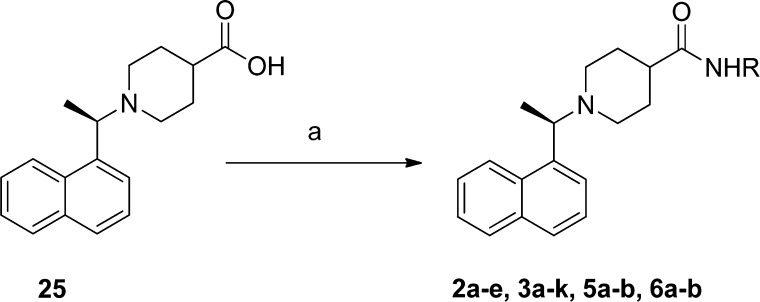

Preparation of (R)-amide analogues is summarized in Scheme 4. The starting (R)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid 25 was prepared according to the method of Ghosh et al.15 Coupling of the acid to various arylmethylamines and arylethylamines was effected either by EDCI in the presence of DIEA or by the uronium-based coupling reagent HATU.

Scheme 4. General Synthesis of Amide Analogues.

Reagents and conditions: (a) RNH2, EDCI or HATU, DIEA.

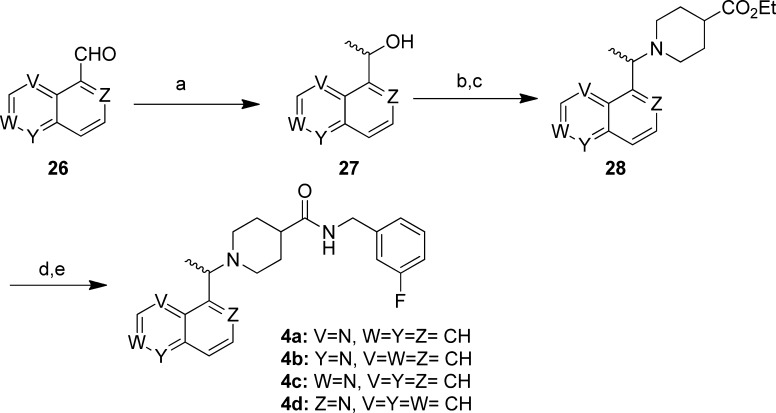

The racemic quinolinyl and isoquinolinyl analogues (4a–c) were generated from the corresponding aldehydes 26a–c by treatment with methylmagnesium chloride to give the methylcarbinols 27a–c (Scheme 5). Alternatively, carbinol 27d was prepared from 1-cyanoisoquinoline by addition of methylmagnesium chloride followed by sodium borohydride reduction of the resulting ketone, as described in the Experimental Section. Displacement of the corresponding mesylates with ethyl isonipecotate afforded esters 28a–d (Scheme 5). Saponification followed by EDCI-mediated coupling with 4-fluorobenzylamine provided the final amides 4a–d.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Quinolinyl- and Isoquinolinylamides.

Reagents and conditions: (a) MeMgCl, THF, −78 °C; (b) Ms2O, DIEA, DCM; (c) ethyl isonipecotate, DCM, rt; (d) 1 M NaOH, MeOH; (e) EDCI, HOBt, DIEA, 3-fluorobenzylamine, THF.

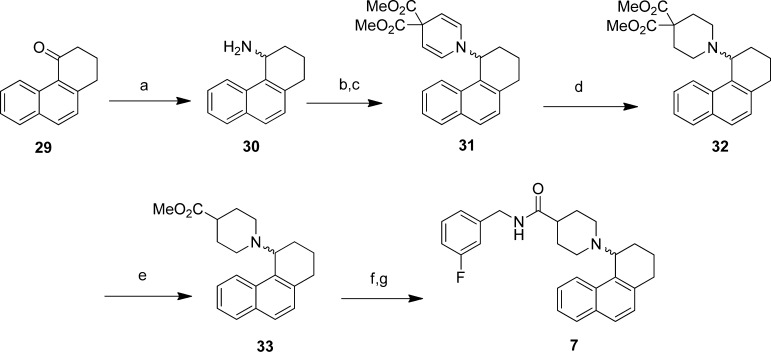

Conformationally restricted analogue 7 was prepared as outlined in Scheme 6. Reductive amination of ketone 29 with ammonium acetate and sodium cyanoborohydride provided amine 30 in quantitative yield. Conversion to piperidine ester 33 was effected with a three-step sequence analogous to that employed in Scheme 3. Saponifiction with LiOH in a mixture (3:1:1) of THF/MeOH/H2O furnished the free acid. Finally amide coupling with 3-fluorobenzylamine, EDCI, HOBt, and DIEA led to the production of the target analogue 7. It is worth noting that the shorter ethyl isonipecotate displacement route used in Schemes 1, 2, and 5 was not successful with the mesylate derived from reduction/mesylation of 29, presumably because of excessive steric hindrance.

Scheme 6. Synthesis of Conformationally Restricted Analogue 7.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaBH3CN, NH4OAc, iPrOH, reflux, 44 h; (b) dimethyl 2,2-bis((1,3-dioxolan-2-yl)methyl)malonate, HCl/THF; (c) 30, NaHCO3, rt, 72 h ; (d) H2, PtO2, EA, 40 psi, 5 h; (e) NaCN, DMF, reflux, 16 h; (f) aq LiOH, THF/MeOH, rt; (g) 3-fluorobenzylamine, EDCI, HOBt, DIEA, rt, 16 h.

Structure–Activity Relationship Analysis

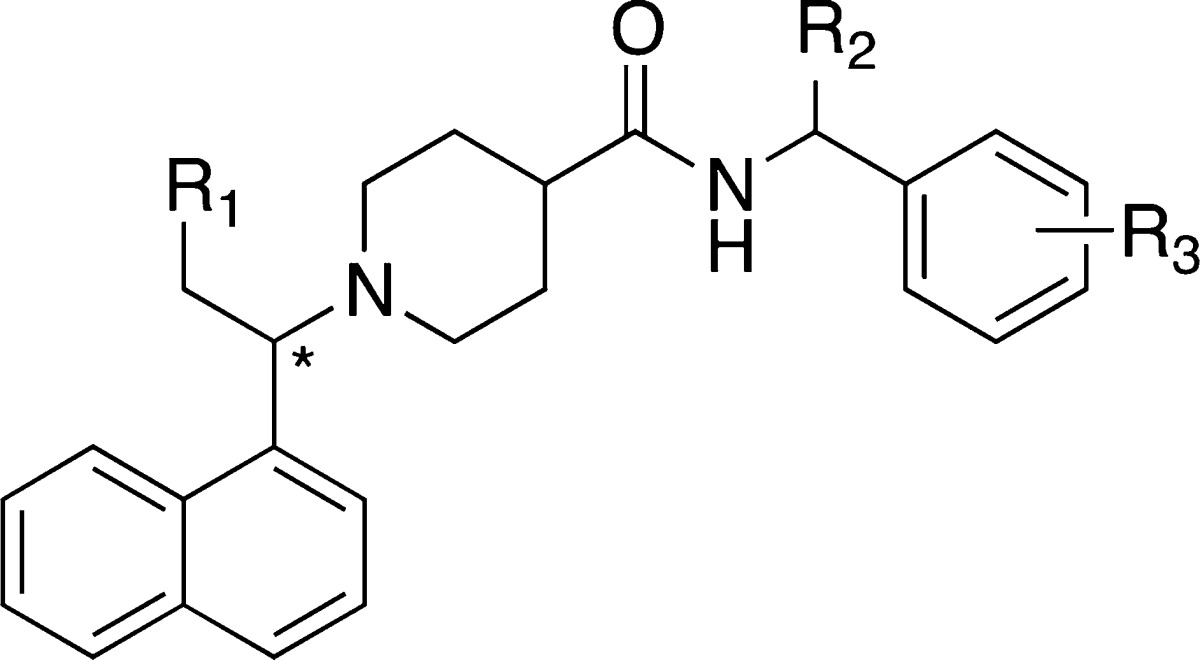

Compound 15g is a competitive inhibitor of SARS-CoV PLpro that displays potent enzymatic inhibition (IC50 = 0.67 μM) and low micromolar antiviral activity against SARS-CoV. It evolved from a small SAR study on the HTS hit 2 (Figure 1) and is therefore an attractive lead for the development of anti-SARS drug candidates.15 Compound 15g is composed of the central piperidine-4-carboxamide core decorated with 1-naphthalenylethyl and 1,3-benzodioxolylmethyl substituents at the piperidinyl and carboxamide nitrogens, respectively. Previous SAR has established the preference for the 1-naphthyl over the 2-naphthyl substitution pattern and the requirement of a single methyl substituent at the methylene linker for effective inhibition (when compared to both unsubstituted and gem-dimethyl derivatives), with minimal stereochemical preference. X-ray crystallographic studies of the SARS-CoV PLpro–15g complex show that the methyl group of the (R)-enantiomer extends into a small pocket that has both hydrophobic and polar features and is filled with water molecules. To explore the dimensions and availability of this pocket to substituents as well as H-bond opportunities, the first set of analogues explores the incorporation of larger or polar substituents (1a, -Me; 1b, -OH; 1c, -OMe; 1d, -Ph) at the methyl group (position R1 in Table 1). Addition of substituents to R1 resulted in higher IC50 values for all substitutions, and loss of inhibitory potency was proportional to substituent size. These trends indicate that the corresponding pocket might be less accessible than predicted by the crystal structure, with no clear opportunities for extra H-bonding or lipophilic interactions. It also appears that the potential entropic gain by displacing the water molecules with larger R1 groups is not achieved likely because of a larger enthalpic penalty of breaking the H-bonds formed between these water molecules and Asp165, Arg167, Tyr274, Thr302, and Asp303. As a result, unlike the previously reported predictions by fragment mapping program (FTMap) in which all water molecules were removed before computational analyses,20 here we demonstrate experimentally that this pocket is unlikely to provide any extra ligand-binding sites or room for larger substituents.

Table 1. In Vitro Analysis of SARS-CoV PLpro Inhibition by 15g and Derivatives.

| compd | isomera | R1 | R2 | R3 | IC50 (μM)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15g | R | H | H | 3,4-O-CH2-O | 0.67 ± 0.03 |

| 1a | R,S | Me | H | 3,4-O-CH2-O | 17.2 ± 2.0 |

| 1b | R,S | OH | H | 3,4-O-CH2-O | 32.0 ± 4.5 |

| 1c | R,S | OMe | H | 3,4-O-CH2-O | >100 |

| 1d | R,S | Ph | H | 3,4-O-CH2-O | >100 |

| 2a | R | H | H | H | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| 2b | R | H | (R)-Me | H | 13.5 ± 1.2 |

| 2c | R | H | (S)-Me | H | 12.7 ± 0.3 |

| 2d | R | H | (R)-CH2-OMe | H | 18.0 ± 1.9 |

| 2e | R | H | (S)-CH2-OMe | H | 1.9 ± 0.1 |

| 3a | R | H | H | 4-Et | 0.47 ± 0.01 |

| 3b | R | H | H | 4-CO-NH-Me | 0.60 ± 0.02 |

| 3c | R | H | H | 3-CO-NH-Me | 0.63 ± 0.01 |

| 3d | R | H | H | 4-NH-CO-Me | 5.7 ± 0.5 |

| 3e | R | H | H | 3-NH-CO-Me | 0.39 ± 0.01 |

| 3f | R | H | H | 3-CH2-NH-CO-Me | 20.4 ± 1.2 |

| 3g | R | H | H | 3-Cl | 27.2 ± 4.1 |

| 3h | R | H | H | 4-Cl | 0.58 ± 0.02 |

| 3i | R | H | H | 3,4-diF | 29.2 ± 2.1 |

| 3j | R | H | H | 4-F | 0.49 ± 0.01 |

| 3k | R | H | H | 3-F | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

Chiral center.

Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation based on a minimum of triplicate measurements.

We next examined the effect of incorporating substituents at the benzylic position R2 to form a second stereogenic carbon, using unsubstituted compound 2a (IC50 = 2.2 ± 0.1 μM) as the comparator. Diastereoisomeric epimers 2b and 2c, with a methyl group at R2, decreased the inhibitory activity by a comparable extent (IC50 of 13.5 ± 1.2 and 12.7 ± 0.3 μM, respectively), indicative of a steric clash with SARS-CoV PLpro. Interestingly, a 10-fold stereopreference was observed for (S)-methoxymethyl 2e (IC50 = 1.9 ± 0.1 μM), compared to epimeric 2d (IC50 = 18.0 ± 1.9 μM), which could be indicative of a H-bond in that region or simply the ability of the more active enantiomer 2e to retain the methoxy in a solvent-exposed environment, thereby avoiding a desolvation penalty. However, because the most active analogue in this series, 2e, did not surpass the effectiveness of the initial unsubstituted compound, 2a, we surmise that substitutions at position R2 do not engage the active site of the enzyme in favorable interaction and are therefore unlikely to lead to activity improvement.

Previous SAR studies on the aromatic substitution pattern of the benzyl group were limited to m- and p-methoxy analogues, which were as potent as the lead benzodioxolane analogue, 15g.15 In the X-ray structure of the SARS-CoV PLpro–15g complex, one of the 1,3-dioxolane oxygens is within 3 Å of the Gln270 side chain amide nitrogen, suggesting the potential for forming an H-bond. However, because of the poor electron density for the Gln270 side chain, the oxygen’s contribution to inhibitory potency was uncertain.15 Therefore, we mutated Gln270 to an alanine, glutamate, or aspartate residue and purified the mutant enzymes and determined the IC50 values with 15g. We found that the IC50 values for the mutant enzymes are the same as for wild type SARS-CoV PLpro, indicating that Gln270 does not contribute to the binding of 15g via interaction with the dioxolane ring (data not shown). As observed with compound 2a, removal of the dioxolane ring from 15g results in a ∼3-fold decrease in potency, suggesting that the dioxolane group provides a significant contribution to inhibitory potency but not through interaction with Gln270. Therefore, to elucidate the nature of interactions provided by the 1,3-benzodioxole group, benzene ring derivatives with diverse substituents at position R3 were explored.

The incorporation of a p-ethyl group at R3 (3a) had a more than 4-fold improvement in potency over unsubstituted prototype 2a, surpassing that of the dioxolane lead (15g). A comparable effect was achieved with both p- and m-methylcarboxamide derivatives 3b (IC50 = 0.60 ± 0.02 μM) and 3c (IC50 = 0.63 ± 0.01 μM) respectively displaying both H-bonding donors and acceptors. Reversal of the amide direction to the acetamido group resulted in significantly differing activity levels for para and meta positional isomers 3d (IC50 = 5.7 ± 0.5 μM) and 3e (IC50 = 0.39 ± 0.01 μM), respectively. Further extension of the acetamido group from the meta position, favored in the previous pair, dramatically decreases activity of the corresponding derivative (3f, IC50 = 20.4 ± 1.2 μM). A reversal in the meta vs para trend is seen with the corresponding pair of chloro derivatives 3g (IC50 = 27.2 ± 4.1 μM) and 3h (IC50 = 0.58 ± 0.01 μM), with the halogen tolerated only at the para position. Finally, derivatives 3j and 3k, featuring the monofluoro substitution at para and meta positions, respectively, displayed a significant improvement over the parental 2a structure, with the 3-fluorobenzyl variant possessing a more than 10-fold higher activity level (IC50 = 0.15 ± 0.01 μM). Surprisingly, 3,4-difluoro substitution in 3i (IC50 = 29.2 ± 2.1 μM) had a significantly detrimental effect, decreasing the inhibitory potency by ∼200-fold when compared to 3k. In general, neither steric nor electronic factors can be invoked to rationalize systematically the effects of the substitution pattern at R3 and R4 on the inhibitory activity, with groups as diverse as 1,3-dioxolane, 4-ethyl, 3- and 4-carboxamido, 3-acetamido, 3- and 4-fluoro, and 4-chloro achieving a similar level of activity, despite presenting a wide range in polarity, size, and H-bonding capacity. Significantly, the monosubstitution at the meta position with the smallest and yet the most electron-withdrawing fluoro group, capable of inducing dramatic polarization effects in the π-system of the associated benzene ring, resulted in the most potent SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitor identified thus far.

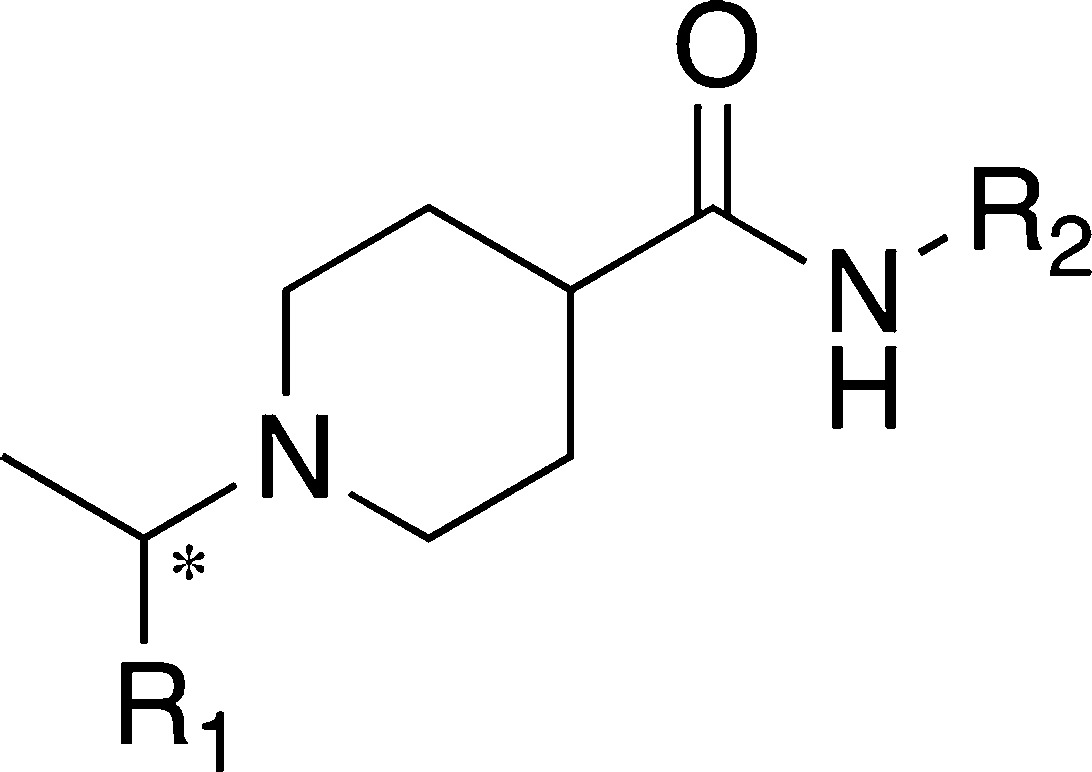

In an attempt to improve the solubility of our most potent compound, 3k, the bioisosteres of naphthalene and benzene (quinoline and pyridine, respectively) were exploited by synthesizing corresponding derivatives (Table 2). A detrimental effect on activity is observed upon replacement of the naphthyl ring system by quinolines (4a, IC50 = 7.0 ± 0.7 μM and 4b, IC50 = 4.5 ± 0.2 μM) and isoquinolines, (4c, IC50 = 6.8 ± 0.3 μM and 4d, IC50 = 30.8 ± 2.6 μM), all tested as racemates. The replacement of the phenyl ring in the 2a prototype by the isosteric 3- and 4-pyridinyls (5a, IC50 = 26.3 ± 2.3 μM and 5b, IC50 = 18.3 ± 0.9 μM) decreased potency by over an order of magnitude. Interestingly, the activity was rescued by the addition of a 3-methoxy group to the 4-pyridinyl ring of the 5b analogue (5c, IC50 = 0.35 ± 0.02 μM), confirming the benefit of having a H-bonding group at C-3 of the aromatic ring. We tested whether Gln270 was involved in an interaction with compound 5c by determining its IC50 value with each of the SARS PLpro mutant enzymes (Gln270Ala, Gln270Asp, and Gln270Glu). We observed no differences in the IC50 values within experimental error, indicating that no significant interaction is involved (data not shown). Analysis of the active site for other potential hydrogen-bonding residues produced no obvious candidates.

Table 2. Structures and Activities of 3k Variants, Exploring Bioisosteric Replacements and Scaffold Perturbation.

| compd | isomera | R1 | R2 | IC50 (μM)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3k | R | 1-naphthyl | 3-F-Ph-CH2 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| 4a | R,S | 8-quinolinyl | 3-F-Ph-CH2 | 7.0 ± 0.7 |

| 4b | R,S | 5-quinolinyl | 3-F-Ph-CH2 | 4.5 ± 0.2 |

| 4c | R,S | 5-isoquinolinyl | 3-F-Ph-CH2 | 6.8 ± 0.3 |

| 4d | R,S | 1-isoquinolinyl | 3-F-Ph-CH2 | 30.8 ± 2.6 |

| 5a | R | 1-naphthyl | 3-pyridinyl-CH2 | 26.3 ± 2.3 |

| 5b | R | 1-naphthyl | 4-pyridinyl-CH2 | 18.3 ± 0.9 |

| 5c | R | 1-naphthyl | 2-methoxy-4-pyridinyl-CH2 | 0.35 ± 0.02 |

| 6a | R | 1-naphthyl | 4-Cl-Ph-CH2CH2 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| 6b | R | 1-naphthyl | 3-F-Ph-CH2CH2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 |

Chiral center.

Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation based on a minimum of triplicate measurements.

Extending the separation of the two aromatic centers in compounds 3h and 3k by one carbon atom resulted in weakening of inhibition activity in corresponding variants 6a (IC50 = 1.6 ± 0.3 μM) and 6b (IC50 = 1.9 ± 0.1 μM). The effect is surprisingly minor, considering the nature of this perturbation, and is perhaps indicative of a significant amount of flexibility in the active site of SARS-CoV PLpro in the region bound by the benzene moiety.

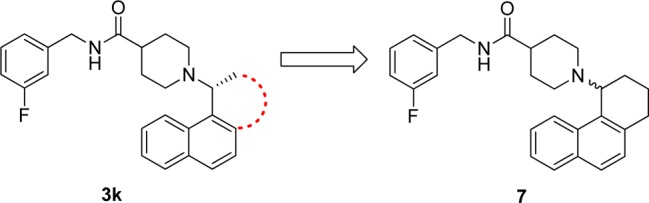

Finally, tricyclic analogue 7 was prepared as a conformationally restricted analogue of our most potent inhibitor 3k (Figure 2). It was designed to lock the conformation of the bond joining C-1 of the naphthyl ring to the piperidinylethyl group to that observed in the X-ray structure of the SARS-CoV PLpro–15g complex. This modification, however, led to a significant loss of activity (IC50 = 5.1 ± 0.5 μM). These results suggest an inhibitor-induced-fit mechanism of association, in which the size and conformational freedom of compound 3k allow the optimal fit to be achieved.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of compound 7. The conformationally restricted analogue 7 was designed to lock the conformation of compound 3k to the conformation observed in the X-ray crystal structure of SARS-CoV PLpro bound to 15g.

X-ray Structural Analyses of SARS-CoV PLpro Bound to 3k and 3j and Comparison to 15g

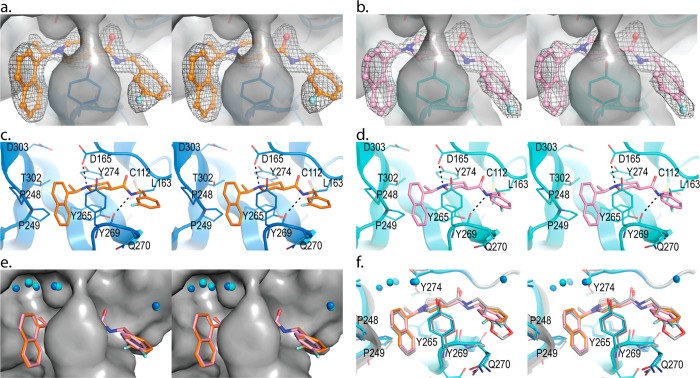

To gain structural insight into the enhanced potency of compound 3k, SARS-CoV PLpro was cocrystallized as a complex with 3k (PDB code 4OW0) and 3j (PDB code 4OVZ) using an approach similar to that for 15g.15 Crystals for each SARS-PLpro complex resulted after screening over 3000 crystallization conditions for diffraction quality crystals. Complete X-ray data sets were collected for the SARS-CoV PLpro–3k and PLpro–3j complexes to resolutions of 2.1 and 2.5 Å, respectively (Table 3). Both SARS-CoV PLpro–inhibitor complexes crystallized in space group C2 and contained two monomers per asymmetric unit.

Table 3. Data Collection and Refinement Statistics.

| 3k | 3j | |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||

| beamline | 21-ID-F | 21-ID-F |

| wavelength (Å) | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| space group | C2 | C2 |

| unit cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 119.4, 74.4, 98.3 | 119.8, 73.5, 98.3 |

| α, β, γ (deg) | 90, 104, 90 | 90, 104, 90 |

| resolution (Å) | 100–2.10 (2.14–2.10) | 100–2.50 (2.54–2.50) |

| no. of reflections observed | 514232 | 743761 |

| no. of unique reflections | 49274 | 29021 |

| Rmerge (%) | 6.2 (52.3) | 6.5 (69.6) |

| I/σI | 20.6 (1.9) | 19.3 (1.8) |

| % completeness | 98.6 (96.1) | 99.8 (100) |

| redundancy | 4.7 (3.9) | 4.2 (4.2) |

| Refinement | ||

| resolution range (Å) | 31.79–2.10 | 35.75–2.50 |

| no. of reflections in working set | 42169 | 24909 |

| no. of reflections in test set | 2134 (5.1%) | 1265 (5.1%) |

| Rwork (%) | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| Rfree (%) | 0.20 | 0.24 |

| average B factor (Å2) | 39 | 37 |

| rmsd from ideal geometry | ||

| bond length (Å) | 0.022 | 0.026 |

| bond angle (deg) | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| most favored (%) | 94.0 | 92.6 |

| allowed (%) | 4.8 | 5.6 |

| disallowed (%) | 1.2 | 1.8 |

After identification of a molecular replacement solution and performance of initial rounds of refinement of the SARS-CoV PLpro structural model in the absence of any ligand or water, strong (>3σ) residual electron density was observed in Fo – Fc maps for both 3k and 3j in the active sites of each monomer within the asymmetric unit. The strong and continuous electron density for the inhibitors allowed for their unequivocal positioning and modeling within the ligand-binding site (Figure 3a and Figure 3b). Both 3k and 3j bind to the SARS-CoV PLpro active site in the same orientation (Figure 3c and Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structures of SARS-CoV PLpro in complex with 3k and 3j. Stereoviews of SARS-CoV PLpro (blue ribbon representation and gray surfaces) in complex with 3k (orange ball and sticks) are shown in (a) and (c), and SARS-CoV PLpro (cyan ribbon representation and gray surface) in complex with 3j (pink ball and sticks) are shown in (b) and (d). The corresponding Fo – Fc electron density omit maps (inhibitor atoms omitted) contoured at 3σ are shown as gray mesh. Important amino acids for inhibitor binding are shown, and the H-bonds between inhibitor atoms and amino acid residues are depicted as dotted lines. A superimposition of SARS-CoV PLpro–3k and PLpro–3j complexes is shown in (e) with conserved water molecules displayed as blue and cyan spheres for the 3k– and 3j– complexes, respectively. A superimposition of SARS-CoV PLpro–15g complex (SARS-CoV PLpro displayed as a gray ribbon and 15g displayed as gray balls and sticks, pdb:3MJ5) with SARS-CoV PLpro–3k and PLpro–3j complex is shown in (f).

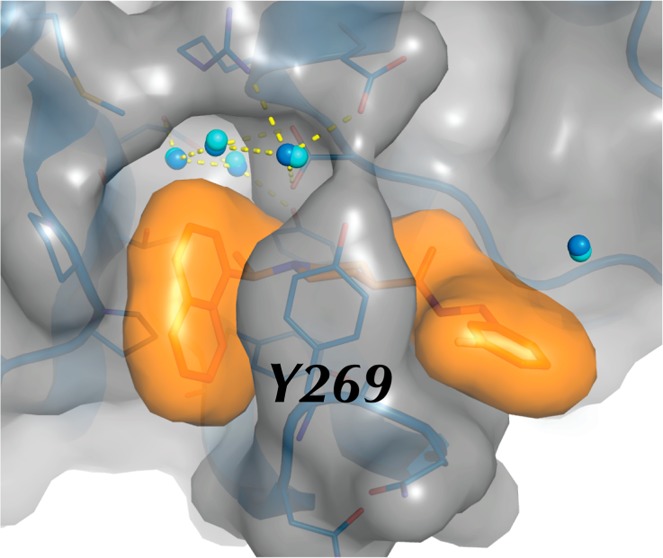

As described previously for compounds 24 and 15g, compounds 3k and 3j bind adjacent to the active site at the enzyme S3–S4 subsites14,15 (Figure 3c and Figure 3d), exclusive of any interactions with the catalytic triad (Cys112-His273-Asp287). Upon inhibitor binding, the β-turn/loop (Gly267-Gly272) containing Tyr269 adopts a closed conformation via an induced-fit mechanism to interact with the inhibitors. This enables the formation of a 3 Å H-bond between the backbone carbonyl of Tyr269 and the carboxyamide nitrogen of the inhibitors. An additional and important interaction is observed between the piperidine ring nitrogen and the side chain carboxylate of Asp165. The puckering of the piperidine ring positions the cationic nitrogen within a distance of 2.8 Å from an oxygen of the carboxylate of Asp165, thereby forming a charge-to-charge mediated H-bond.

A structural superimposition of the two SARS-CoV PLpro–3k and PLpro–3j complexes (Figure 3e) shows that the 1-naphthyl rings align identically and that they pack against the two tandem prolines, Pro248 and Pro249, in a hydrophobic pocket formed by the side chains of the prolines, Tyr265, Tyr269, and Thr302 (Figure 3c and Figure 3d). This pocket orients the (R)-methyl group into a small cavity lined by hydrophobic and hydrophilic side chains wherein some H-bond opportunities exist with the side chains of Asp303, Thr302, and Tyr274. The enhanced resolution of PLpro–3k and PLpro–3j complex compared to PLpro–15g complex allowed for the better placement of three conserved water molecules that are present within this cavity (Figure 3e). The presence of these water molecules increases the polarity and decreases the effective size of the otherwise larger and mostly hydrophobic cavity. This smaller cavity explains our observed SAR with hydrophobic or polar extensions at the (R)-methyl (position R1 in Table 1) whereby the larger groups were all detrimental to binding affinity. These observations suggest that the potential entropic gain in binding energy by displacement of the water molecules cannot be achieved by incorporation of larger or polar substituents, as the enthalpy necessary to break the H-bonds between water molecules and the side chains must be too large to overcome.

A superimposition of PLpro in complex with 15g, 3k, and 3j is shown in Figure 3f. As discussed above, previous structural and computational analyses of the 15g-bound structure showed that the 1,3-benzodioxole moiety can move within 3 Å of the amide nitrogen of Gln270 side chain. However, mutation of Gln270 to Ala, Glu, or Asp showed no significant change in inhibitory potency when tested against 15g, 3k, and 3j, indicative of no H-bond interactions with the side chain of Gln270. Interestingly, while the superimposition between PLpro–15g, PLpro–3k, and PLpro–3j complexes shows a near perfect overlap of the 1-naphthyl rings, there is a 1 Å difference in the position of the carboxamide nitrogen of 15g when compared to 3k and 3j. This causes a slight tilt on the orientations of the benzene rings to allow for the accommodation of the different benzene substituents. As a result, we conclude that the slightly enhanced inhibitory activity of compound 3k compared to 3j and 15g is due to its ability to form collectively stronger van der Waals’ interactions between the m-fluorobenzene and the side chain of Tyr269, and slightly stronger interactions with the backbone oxygen atoms of Tyr269 and Gln270 (Figure 3f).

Assessing Potency and Selectivity of SARS-CoV PLpro Inhibitors to Human and Viral USP Homologues

The development of an enzyme inhibitor with broad-spectrum specificity is an attractive approach for the treatment of infections caused by current and future-emerging human coronaviruses. However, to avoid drug-induced toxicity and potential side effects, it is crucial to maintain high inhibitory potency without cross-reactivity of critical homologues, the cellular deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). First, to assess compound selectivity, a set of the most potent analogues were tested against a panel of human DUBs, including representative ubiquitin specific proteases (USPs) with structural similarity to PLpro, along with the human cysteine proteases caspase 3 and cathepsin K (Table 4). Compounds were tested at 31 μM. If the inhibitory activity was less than 10%, no inhibition is reported. If the inhibitory activity was between 10% and 15% or between 15% and 20%, then IC50 values of >100 or 31 μM are reported. Importantly, we can detect no significant inhibition of the human DUBs or cysteine protease enzymes tested above 20% at 31 μM, indicating that these PLpro inhibitors are selective and are unlikely to have significant off-target activity.

Table 4. Inhibitor Selectivity against Human DUBs and Cysteine Proteases.

| IC50 (μM)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15g | 3k | 3e | 3j | |

| human DUB | ||||

| USP2 | – | – | >100 | – |

| USP7 | – | – | >100 | – |

| USP8 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| USP20 | – | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| USP21 | >31 | >31 | >31 | >31 |

| DEN1 | – | – | – | – |

| UCHL1 | – | – | – | – |

| caspase 3 | – | – | – | – |

| cathepsin K | – | – | – | – |

–, no inhibition.

Next, we evaluated the potential of this set of analogues for the development of broader-spectrum coronaviral inhibitors. All of the analogues in Tables 1 and 2 were counterscreened against the viral orthologue PLP2 enzyme from the human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63), a member of the α-coronaviruses. HCoV-NL63 is one of the causative agents of croup in children, and infection can result in hospitalization.21 Currently there are no specific treatments for individuals infected with HCoV-NL63. For those analogues that showed >30% inhibition at a single dose concentration of 100 μM, full dose response curves of HCoV-NL63 PLP2 inhibition versus increasing compound concentration up to 100 μM were determined. Six compounds, including compound 3k, produced typical dose response curves, and the inhibition data were fit to determine the IC50 and maximum percent inhibition values (Table 5). The results show that inhibition of HCoV-NL63 PLP2 is achieved by this series of compounds, albeit significantly weaker inhibition than for SARS-CoV PLpro (micromolar versus nanomolar range), and suggest that SARS-CoV PLpro and HCoV-NL63 PLP2 may display sufficient structural similarities at the active site for the potential development of a dual-target inhibitor.

Table 5. Compounds Displaying Dual-Target Inhibition of SARS-CoV PLpro and HCoV-NL63 PLP2.

| IC50 (μM) |

max I (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | PLpro | PLP2 | PLpro | PLP2 |

| 15g | 0.67 | 18 | 99 | 46 |

| 3k | 0.15 | 33 | 100 | 57 |

| 5c | 0.35 | 59 | 100 | 67 |

| 3e | 0.39 | 46 | 100 | 71 |

| 3d | 5.7 | 37 | 94 | 42 |

| 3i | 29 | 44 | 78 | 48 |

SARS-CoV Antiviral Activity and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of the Most Potent Compounds

Compound 3k exhibits lower topological polar surface area (tPSA = 32.2 Å2) relative to the initial inhibitor 15g (tPSA = 50.8 Å2) and therefore is proposed to enhance cell permeability and thus antiviral activity relative to 15g. On the basis of these possible improvements, compound 3k along with seven of the most potent analogues and two quinolone derivatives were subjected to antiviral assays using our well-established method and BSL-3 protocols.14 In this assay, compounds are titrated in both mock- and SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells, and the resulting dose–response curves are fitted to the four-parameter logistic equation. Curves were then compared to the mock-infected cells to assess drug-induced cytotoxicity in Vero E6 and HEK293 cell lines. The resultant EC50 values and cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) are shown in Table 6. Because of their greater potency, all tested compounds displayed low cytotoxicity levels (CC50 > 68 μM) with improved therapeutic index (TI) values in Vero E6 cell when compared to 15g. Compounds with IC50 values of >2 μM (2a, 4a, and 4c) had no antiviral activity displaying EC50 values of >50 μM (data not shown). Compounds 3e, 5c, 3j, and 2e displayed similar to slightly improved antiviral activity when compared to the initial compound 15g. However, in the case of our best compound, 3k, which has a 4-fold improved IC50 value, an additional 2-fold improvement in antiviral activity was observed (EC50 = 5.4 ± 0.6 μM) when compared to 15g.

Table 6. Compound Effect on Replication of SARS-CoV Virus, Cytotoxicity, and Therapeutic Indexes.

| 15g | 3k | 3e | 5c | 3j | 2e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vero E6 | ||||||

| IC50 a | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 1.9 ± 0.1 |

| EC50 a | 12.8 ± 1.4 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 9.5 ± 1.3 | 11.6 ± 0.8 | 11.7 ± 0.7 |

| CC50 a | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| TI | >7.8 | >18.5 | >12 | >10.5 | >8.6 | >8.5 |

| HEK293 | ||||||

| CC50 a | >100 | 73 ± 19 | 68 ± 15 | >100 | 73 ± 29 | >100 |

Values are reported in μM as mean ± standard deviation based on a minimum of triplicate measurements. EC50 values were derived from two independent experiments. EC50, the half maximal effective concentration in SARS-CoV infected Vero E6 cells; CC50, 50% cytotoxic concentration; TI, the therapeutic index defined as the ratio of CC50/EC50.

Metabolic Stability and Plasma Binding Studies

With the ultimate goal of achieving protection from coronaviral infection in vivo, we evaluated the stability of our best new analogues to phase I metabolism by mouse liver microsomes (Table 7). The lead compound 15g proved to be exceedingly unstable, being completely consumed within 15 min. This was not entirely unexpected because of the presence of the 3,4-methylenedioxy moiety, which renders the benzyl aromatic ring electron-rich and is itself a known target of cytochrome P450s.22,23 Somewhat surprisingly, the much more electron-poor 3-fluorobenzylamide 3k was still metabolized rapidly, suggesting that most of the metabolism is occurring distal to the benzylamide. Consistent with this hypothesis, the less lipophilic bis(amide) 3e and methoxypyridine 5c were significantly more stable, with 20% and 30% parent drug remaining after 15 min, respectively, and half-lives 4- to 5-fold longer than that of 15g.

Table 7. Stability of Selected Compounds to Metabolism by Mouse Liver Microsomesa.

Percent of the parent compound remaining after 15 min incubation. The initial concentration of the parent compound was 1 μM.

Half-life (minutes) of parent compound.

Because the binding of an antiviral drug to human serum proteins may result in reduced antiviral activity,24 we evaluated the plasma binding ability of the compounds in Table 6 by measuring the shifts in their IC50 values in various concentrations of human plasma protein (serum shift assays).25 We observed no significant changes in the IC50 values for the compounds in the serum shift assays, which were performed in the presence of 5%, 10%, and 20% human serum albumin (HSA) (data not shown), the most abundant protein in human plasma (40 mg/mL).26 This observation suggests that no specific interactions between the compounds and HSA take place.

Conclusions

A second-generation series of highly potent SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitors was designed and evaluated biologically to further advance anticoronavirus drug development. Four compounds (3k, 3e, 3j, and 5c) were found to have more potent SARS-CoV PLpro inhibition and SARS-CoV antiviral activity than the most potent first generation inhibitor, 15g. None of these five compounds exhibit cytotoxicity or off-target inhibitory activity of a series of human DUB and cysteine protease enzymes, nor do any of these five inhibitors bind to human serum albumin (HSA). The second-generation compounds 3k, 3e, and 5c exhibit significantly improved metabolic stability compared to 15g. Although compound 3k is the most potent SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitor (IC50 = 0.15 μM) and the most effective antiviral compound in cell culture (EC50 = 5.4 μM), it is significantly less metabolically stable compared to compounds 3e and 5c, which are similarly effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV PLpro (IC50 = 0.39 μM and IC50 = 0.35 μM) and inhibiting SARS-CoV infected Vero cells (EC50 = 8.3 μM and EC50 = 9.5 μM). Thus, compounds 3e and 5c are likely to be the better candidates to advance to animal efficacy models. Finally, the high resolution of the inhibitor-bound crystal structures of PLpro with 3k and 3j revealed novel aspects for the inhibitor binding mode, providing guidance for the further optimization of PLpro inhibitors.

Experimental Section

General Synthetic Procedures

All reagents were used as received from commercial sources unless otherwise noted. 1H and 13C spectra were obtained in DMSO-d6 or CDCl3 at room temperature, unless otherwise noted, on Varian Inova 400 MHz, Varian Inova 500 MHz, Bruker Avance DRX 500, or Bruker Avance DPX 300 instrument. Chemical shifts for the 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in parts per million (ppm) on the δ scale from an internal standard of residual tetramethylsilane (0 ppm). Rotamers are described as a ratio of rotamer A to rotamer B if possible. Otherwise, if the rotamers cannot be distinguished, the NMR peaks are described as multiplets. Mass spectrometry data were obtained on a Waters Corporation LCT. Purity of all tested compounds was assessed by HPLC using an Agilent 1100 series with an Agilent Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (254 nm detection) with the following gradient: 10% ACN/water (1 min), 10–90% ACN/water (6 min), and 90% ACN/water (2 min). Values for each compound are included at the end of each experimental procedure, and all are over 95% pure. HPLC retention times (tR) were recorded in minutes (min). Solvent abbreviations used are the following: MeOH (methanol), DCM (dichloromethane), EtOAc (ethyl acetate), Hex (hexanes), DMSO (dimethylsulfoxide), DMF (dimethylformamide), H2O (water), THF (tetrahydrofuran), ACN (acetonitrile). Reagent abbreviations used are the following: HATU (O-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate), HOAT (1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole), HOBt (1-hydroxy-1,2,3-benzotriazole), EDCI (N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride), DIEA (diisopropylethylamine), TFA (trifluoroacetic acid), MgSO4 (magnesium sulfate), Na2SO4 (sodium sulfate), NaHCO3 (sodium bicarbonate), Na2CO3 (sodium carbonate), Cs2CO3 (cesium carbonate), NH4Cl (ammonium chloride), K2CO3 (potassium carbonate), KOH (potassium hydroxide), HCl (hydrogen chloride), NaOH (sodium hydroxide), LiOH (lithium hydroxide), LAH (lithium aluminum hydride), EtOH (ethanol), NaCN (sodium cyanide), Et2O (diethyl ether), CsF (cesium fluoride), NaCl (sodium chloride), TBSCl (tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride), Ms2O (methanesulfonic anhydride), MsCl (methanesulfonyl chloride), AcOH (acetic acid), NaBH4 (sodium borohydride), NaBH3CN (sodium cyanoborohydride), H2 (hydrogen), N2 (nitrogen), MS (molecular sieves). Assay abbreviations are the following: LUC (luciferase), MTT ((3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide. Additional abbreviations are the following: aq (aqueous), saturated (saturated), rt (room temperature). All anhydrous reactions were run under an atmosphere of dry nitrogen.

(±)-N-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-ylmethyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)propyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (1a)

Ethyl 1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)propyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate 11a (480 mg, 1.48 mmol) was dissolved in a 1:1:2 mixture of THF/EtOH/1 M aqueous NaOH, total volume of 8 mL. This was stirred at 60 °C for 5 h. The mixture was allowed to cool, and the organic solvents in the mixture were mostly removed by rotary evaporation. The pH was then reduced by addition of concentrated HCl to ∼pH 4, and the resulting white precipitate was collected over a filter to give the desired carboxylic acid (364 mg, 83%) without further purification. Then the following was added sequentially to anhydrous DMF (1 mL): 3 Å molecular sieves, 1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)propyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid (50 mg, 0.17 mmol), DIEA (0.088 mL, 0.504 mmol), EDCI (36 mg, 0.19 mmol), HOBt (28 mg, 0.19 mmol), and finally piperonylamine (0.031 mL, 0.252 mmol). This was stirred at room temperature for 16 h, at which time the material was partitioned between 10% Na2CO3 solution and EtOAc, and the organic layer was washed with 10% Na2CO3 solution (3 × 20 mL) and brine (1 × 20 mL). The organic layer was dried with anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification was accomplished via flash chromatography (4 g silica RediSep gold column on a CombiFlash, eluted with 70% EtOAc/Hex) to give the desired product (34 mg, 47%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.44 (bs, 1H), 7.91–7.84 (m, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.40 (m, 4H), 6.78–6.66 (m, 3H), 5.94 (s, 2H), 5.87–5.81 (m, 1H), 4.32 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.93 (bs, 1H), 3.39–3.26 (m, 1H), 2.94–2.80 (m, 1H), 2.25 (bs, 1H), 2.06–1.66 (m, 8H), 0.68 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 431.1. HPLC tR = 5.85 min, >95% purity.

(±)-N-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-ylmethyl)-1-(2-hydroxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (1b)

Silyl ether 17 (46 mg, 0.08 mmol) was dissolved in ACN (4 mL) and H2O (2 mL). To this was added CsF (51 mg, 0.34 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The mixture was then partitioned between 10% aqueous Na2CO3 (30 mL) and EtOAc (50 mL) and extracted. The extract was dried with anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was then purified by flash chromatography (4.7g amine-activated silica RediSep column, 50% EtOAc/Hex) to give the final product (28 mg, 77%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.29 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.87–7.81 (m, 1H), 7.58–7.45 (m, 4H), 6.81–6.64 (m, 3H), 5.95 (s, 2H), 5.69 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.64–4.49 (m, 1H), 4.32 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.09 (dd, J = 11.0, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (dd, J = 10.9, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 3.27 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 3.00 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 2.32–1.75 (m, 7H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 433.1, (M + Na) 455.1. HPLC tR = 5.43 min, >95% purity.

(±)-N-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-ylmethyl)-1-(2-methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (1c)

Ethyl 1-(2-methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate 11c (80 mg, 0.23 mmol) was dissolved in EtOH (2 mL) and 6 M NaOH (5 mL). This was stirred at 50 °C for 3 h. The pH was dropped to 2 by dropwise addition of concentrated HCl, and material was extracted with 1:1 EtOAc/Et2O (3 × 10 mL). The solvent was then dried with anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and removed in vacuo to give 1-(2-methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid (30 mg, 41%) without further purification. Then the following was added sequentially to anhydrous DMF (1 mL): 3 Å molecular sieves, 1-(2-methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid (20 mg, 0.06 mmol), DIEA (0.033 mL, 0.191 mmol), EDCI (14 mg, 0.07 mmol), HOBt (11 mg, 0.07 mmol), and finally piperonylamine (0.012 mL, 0.096 mmol). This was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, at which time the material was partitioned between 10% aqueous Na2CO3 solution and EtOAc, and the organic layer was washed with 10% aqueous Na2CO3 solution (3 × 10 mL) and brine (1 × 10 mL). The organic layer was dried with anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The material was purified via alumina flash chromatography (8 g basic alumina RediSep cartridge, 30% EtOAc/Hex) to give the final desired compound (13 mg, 46%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.37 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.54–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.45 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.79–6.71 (m, 3H), 5.96 (s, 2H), 5.73 (s, 1H), 4.34 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (s, 1H), 3.93 (dd, J = 10.1, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (dd, J = 10.3, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 3.31 (s, 3H), 2.85 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 2.24 (t, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 2.16–2.09 (m, 1H), 2.07–1.69 (m, 5H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 447.1, (M + Na) 469.1. HPLC tR = 5.97 min, >95% purity.

(±)-N-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-ylmethyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)-2-phenylethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (1d)

Methyl 1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)-2-phenylethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate 23 (38 mg, 0.10 mmol) was dissolved in a 1:1:2 mixture of THF/EtOH/1 M aqueous NaOH, total volume of 4 mL. This was stirred at 60 °C for 4 h. The mixture was allowed to cool, and the pH was reduced by addition of concentrated HCl to ∼pH 4, and the resulting white precipitate was collected over a filter to give 1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)-2-phenylethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid (30 mg, 82%) as a white powder. Then the following was added sequentially to anhydrous DMF (1 mL): 3 Å molecular sieves, 1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)-2-phenylethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid (30 mg, 0.08 mmol), DIEA (44 μL, 0.25 mmol), EDCI (18 mg, 0.09 mmol), HOBt (14 mg, 0.09 mmol), and piperonylamine (16 μL, 0.13 mmol). This was stirred at room temperature for 17 h, at which time the material was partitioned between 10% aqueous Na2CO3 solution and EtOAc, and the organic layer was washed with 10% aqueous Na2CO3 solution (3 × 20 mL) and brine (1 × 20 mL). The organic layer was dried with anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was then purified by flash chromatography (10 g silica, 50% EtOAc/Hex) to give the final product (20 mg, 44%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.47 (bs, 1H), 7.86–7.80 (m, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (dt, J = 6.3, 3.3 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (bs, 2H), 7.12–7.00 (m, 3H), 6.89 (bs, 2H), 6.77–6.70 (m, 3H), 5.95 (s, 2H), 5.83–5.74 (m, 1H), 4.33 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.46 (dd, J = 13.6, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.41 (s, 1H), 3.20 (dd, J = 13.6, 9.1 Hz, 1H), 2.95 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 2.15–2.04 (m, 3H), 1.91–1.70 (m, 4H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 493.1, (M + Na) 515.1. HPLC tR = 6.22 min, >95% purity.

General Amide Coupling Method A

To a solution of HOAT (0.07 g, 0.35 mmol) in dry DMF (5 mL) were added HATU (0.19 g, 0.49 mmol), (R)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid 25 (0.1 g, 0.35 mmol), and amine (0.42 mmol) followed by DIEA (0.05 g, 0.35 mmol). The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature, then diluted with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and extracted with EtOAc (3×). The combined organic extracts were washed with saturated NaCl (3×), dried (MgSO4), and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel flash chromatography (1–4% MeOH/DCM).

General Amide Coupling Method B

To a solution of (R)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid 25 (0.06 g, 0.21 mmol) in dry DMF (5 mL) were added EDCI (0.05 g, 0.28 mmol), HOBt (0.04 g, 0.25 mmol), and DIEA (0.07 mL, 0.53 mmol), followed by amine (0.21 mmol) and stirred overnight at room temperature. After this time, the reaction mixture was diluted with saturated NaHCO3 and extracted with EtOAc (3×). The combined organic extracts were washed with saturated NaCl (3×), dried (MgSO4), and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel flash chromatography (1–5% MeOH/DCM).

(R)-N-Benzyl-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (2a)

Coupling method A: 42% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.44 (br s, 1H), 7.80–7.90 (m, 1H), 7.75–7.79 (m, 1H), 7.23–7.61 (m, 10H), 5.88 (s, 1H), 5.45 (br s, 1H), 4.32 (m, 2H), 4.20 (br s, 1H), 3.23–3.34 (m, 1H), 2.88–2.91 (m, 2H), 1.84–2.03 (m, 4H), 1.43 (m, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 373.2. HPLC tR = 5.8 min, >95% purity.

1-((R)-1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)-N-((R)-1-phenylethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (2b)

Coupling method A: 33% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.44 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.86–7.88 (m, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 6.48, 1H), 7.56 (br s, 1H), 7.42–7.48 (m, 3H), 7.32–7.34 (m, 5H), 5.68 (br s, 1H), 5.13–5.16 (m,1H), 4.13 (br s, 1H), 3.25 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 2.29 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 2.02–2.10 (m, 2H), 1.89–1.91 (m, 1H), 1.67–1.79 (m, 4H), 1.46–1.48 (m 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 387.2. HPLC tR = 5.9 min, >95% purity.

1-((R)-1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)-N-((S)-1-phenylethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (2c)

Coupling method A: 23% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6 and CDCl3) δ 8.22 (m, 1H), 7.86–8.1 (m, 2H), 7.72–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.32–7.48 (m, 4H), 7.32–7.38 (m, 3H), 6.96 (br s, 1H), 5.11 (br s, 1H), 4.89–4.91 (m, 1H), 5.13–5.16 (m,1H), 4.65–4.4.69 (m, 1H), 3.72–3.79 (m, 2H), 3.68–3.72 (m, 1H), 3.68–3.65 (m, 1H), 2.29 (m, 1H), 2.02–2.12 (m, 1H), 1.89–1.91 (m, 1H),1.62–1.74 (m, 3H), 1.46–1.48 (m 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 387.2. HPLC tR = 5.9 min, >95% purity.

N-((R)-2-Methoxy-1-phenylethyl)-1-((R)-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (2d)

Coupling method B: 60% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.43 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.82–7.85 (m, 1H), 7.73 (m, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.43–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.46 (m, 5H), 6.17 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.09–4.11 (m,1H), 3.63 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 3.31 (s, 3H), 3.23 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 2.89 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 1.99–2.27 (m, 3H), 1.57–1.95 (m, 4H), 1.47 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 417.2. HPLC tR = 5.6 min, >95% purity.

N-((S)-2-Methoxy-1-phenylethyl)-1-((R)-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (2e)

Coupling method B: 52% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.43 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.82–7.84 (m, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.52 (m, 2H), 6.99–7.35 (m, 5H), 6.12 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 5.14 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.10 (m,1H), 3.63 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 3.32 (s, 3H), 3.22 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 2.88 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H), 1.99–2.28 (m, 3H), 1.95–1.50 (m, 4H), 1.46 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 417.2. HPLC tR = 5.6 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(4-Ethylbenzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3a)

Coupling method B: 26% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.41 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.82–7.83 (m, 1H), 7.71–7.73 (m, 1H), 7.39–7.45 (m, 4H), 7.12–7.16 (m, 4H), 5.68 (m, 1H), 4.37 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.99–4.20 (m, 1H), 3.22 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 2.87 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 2.61 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.91–2.24 (m, 4H), 1.57–1.81 (m, 3H), 1.45 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.20 (td, J = 7.6, 0.6 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 401.1. HPLC tR = 5.9 min, 94% purity.

(R)-N-(4-(Methylcarbamoyl)benzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3b)

Coupling method B: 50% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.38 (s, 1H), 7.76–7.99 (m, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.70 (m, 2H), 7.53–7.32 (m, 4H), 7.20–7.32 (m, 2H), 6.20 (s, 2H), 4.42 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.16 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 3.22 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 2.93–3.09 (m, 2H), 2.91 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 1.32–2.28 (m, 9H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 430.2. HPLC tR = 4.7 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(3-(Methylcarbamoyl)benzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3c)

To a solution of tert-butyl 3-(methylcarbamoyl)benzoic acid (0.3 g, 1.1 mmol) in dry DMF (15 mL) were added EDCI (0.26 g, 1.36 mmol), HOBt (0.21 g, 1.36 mmol), and DIEA (0.39 mL, 2.27 mmol), followed by methanamine (0.03 g, 1.10 mmol). The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. After dilution with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (2×). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated NaCl (3×) and dried (MgSO4), concentrated in vacuo, and purified by flash chromatography (1–4% MeOH/DCM) to provide the intermediate (0.1g, 54%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.61–7.69 (m, 2H), 7.28–7.41 (m, 3H), 4.32 (br s, 2H), 2.99 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 3H), 1.49 (s, 9H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 165.1. This material was treated with 4 M HCl in dioxane and stirred overnight at room temperature. After being concentrated in vacuo, the crude 3-(aminomethyl)-N-methylbenzamide was coupled with 25 using method B to afford the desired compound (0.02 g, 11%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.40 (s, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, 2H), 7.37–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.35 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (m, 1H), 5.87 (m, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 4.11 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (s, 1H), 2.99 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.91 (s, 1H), 0.75–2.24 (m, 13H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 430.3. HPLC tR = 4.8 min, 92% purity.

(R)-N-(4-Acetamidobenzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3d)

Coupling method B: 23% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.76–7.89 (m, 3H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.49 (m, 5H), 6.22 (m, 1H), 5.83 (m, 1H), 4.08 (q, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 3.12 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 2.81 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 2.13–2.40 (m, 1H), 1.95–2.15 (m, 2H), 1.84–1.97 (m, 1H), 1.64–1.84 (m, 3H), 1.45 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 430.3. HPLC tR = 5.19 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(3-Acetamidobenzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3e)

Coupling method B: 90% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.41 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.78–7.93 (m, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.64 (m, 5H), 7.23 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (s, 1H), 4.36 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.90–4.25 (m, 2H), 3.21 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 2.87 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 1.94–2.24 (m, 5H), 1.53–1.94 (m, 2H), 1.45 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.24 (td, J = 7.1, 0.6 Hz, 2H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 430.1. HPLC tR = 5.0 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(3-(Acetamidomethyl)benzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3f)

To a solution of 1,3-phenylenedimethanamine (0.2 g, 1.4 mmol) in THF (20 mL) was added acetic anhydride (0.07 mL, 0.73 mmol) in THF (10 mL) dropwise. The resulting mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature, then concentrated, and the residue was purified by silica gel flash chromatography (1–5% MeOH/DCM), providing N-(3-(aminomethyl)benzyl)acetamide (0.06 g, 23% yield, TOF ES+ MS, (M + H) 178.1) which was subsequently coupled with 25 using method B to afford the final compound (0.02 g, 12%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.42 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.76–7.94 (m, 1H), 7.73 (m, 1H), 7.49–7.62 (m, 5H), 7.32–7.48 (m, 3H), 4.08 (m, 2H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 3.12 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 2.80 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 2.23–2.27 (m, 1H), 1.91–2.06 (m, 2H), 1.64–1.81 (m, 6H), 1.44 (dd, J = 6.7, 3.7 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 444.3. HPLC tR = 5.4 min, 94% purity.

(R)-N-(3-Chlorobenzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3g)

Coupling method A: 22% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.79–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.23–7.26 (m, 5H), 7.32–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.11–7.13 (m, 1H), 5.81 (br s, 1H), 4.40 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (s, 1H), 3.57–3.61 (m, 1H), 2.90–2.95 (m, 1H), 2.28–1.93 (m, 6H), 1.45 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 407.2. HPLC tR = 4.3 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(4-Chlorobenzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3h)

Coupling method B: 29% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.39 (s, 1H), 7.79–7.96 (m, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.32–7.66 (m, 5H), 7.19–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.01–7.19 (m, 2H), 5.73 (br s, 1H), 4.36 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 4.11 (br s, 1H), 3.22 (d, J = 10.9, 1H), 2.89 (br s, 1H), 1.73–2.09 (m, 6H), 1.47 (s, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 407.1. HPLC tR = 5.7 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(3,4-Difluorobenzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3i)

Coupling method A: 31% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.79–7.81 (m, 3H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.43- 7.51 (m, 3H), 7.03–7.12 (m, 2H), 6.96 (br s, 1H), 5.83 (br s, 1H), 4.37 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.59–3.64 (m, 1H), 3.32–3.39 (m, 1H), 2.91–2.94 (m, 1H), 1.93–2.28 (m, 3H), 1.75–1.89 (m, 4H), 1.43 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 409.2. HPLC tR = 5.78 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(4-Fluorobenzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3j)

Coupling method B: 38% yield. 8.42–8.44 (m, 1H), 7.85–7.87 (m, 1H), 7.73–7.74 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.56 (m, 1H), 7.46–7.54 (m, 3H), 7.20–7.22 (m, 3H), 7.01–7.11 (m, 2H), 5.73 (s, 1H), 4.38–4.39 (d, J = 4.8 Hz 2H), 4.09–4.11 (m, 1H), 3.22 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 2.89 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 1.91–2.06 (m, 3H), 1.71–1.84 (m, 3H), 1.47 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 391.2. HPLC tR = 5.9 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(3-Fluorobenzyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (3k)

Coupling method B: 12% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.43 (s, 1H), 7.84–7.85 (m, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.57 (m, 1H), 7.41–7.48 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.27 (m, 1H), 7.02–7.06 (m, 1H), 6.93–6.95 (m, 1H), 5.75 (s, 1H), 4.42 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 4.12 (br s, 1H), 3.24 (d, J = 7.8, 1H), 2.90 (d, J = 9.7, 1H), 1.99–2.14 (m, 2H), 1.90–1.93 (m, 1H), 1.57–1.80 (m, 5H), 1.46 (s, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 391.2. HPLC tR = 5.7 min, >95% purity.

N-(3-Fluorobenzyl)-1-(1-(quinolin-8-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (4a)

Ethyl 1-(1-(quinolin-8-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate 28a (0.38 g, 1.30 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (20 mL), followed by the addition of 1 N sodium hydroxide (2.6 mL, 2.6 mmol) in one portion. The resulting mixture was stirred for 18 h at room temperature, then concentrated in vacuo and partitioned between ether and a minimum amount of water. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was treated with AcOH dropwise until the solution was acidic by pH paper. The solution was then concentrated in vacuo and dried under high vacuum overnight at room temperature, and the resulting acid was used without further purification. To a solution of (R,S)-1-(1-(quinolin-8-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid (0.1 g, 0.35 mmol) in dry DMF (5 mL) was added EDCI (0.07 g, 0.35 mmol), HOBt (0.07 g, 0.42 mmol), and DIEA (0.06 mL, 0.35 mmol) followed by (3-fluorophenyl)methanamine (0.04 g, 0.35 mmol). This reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature, after which it was diluted with saturated NaHCO3 and extracted with EtOAc (1×). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated NaCl (3×) and dried (MgSO4), then concentrated and purified by silica flash chromatography (1–5% MeOH/DCM) to obtain 4a (0.05 g, 33% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.75–8.98 (m, 2H), 8.35 (m, 1H), 8.27 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.60–7.72 (m, 1H), 7.42–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.42 (m, 2H), 7.00 (ddd, J = 23.3, 16.7, 9.5 Hz, 2H), 3.84–4.40 (m, 4H), 2.94 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 2.76 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 1.88–2.30 (m, 2H), 1.39–1.76 (m, 2H), 1.37 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 392.2. HPLC tR = 4.1 min, >95% purity.

N-(3-Fluorobenzyl)-1-(1-(quinolin-5-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (4b)

Ethyl 1-(1-(quinolin-5-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate 28b (0.67 g, 2.15 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (20 mL), followed by 1 N sodium hydroxide (4.29 mL, 4.29 mmol) in one portion. The resulting mixture was stirred 18 h at room temperature, concentrated in vacuo, and partitioned between ether and a minimum amount of water. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was treated with AcOH dropwise until the solution measured acidic by pH paper. The solution was concentrated in vacuo, dried under high vacuum, and the resulting carboxylic acid was used without further purification in the next step. To a solution of (R,S)-1-(1-(quinolin-5-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid (0.100 g, 0.352 mmol) in dry DMF (5 mL) were added EDCI (0.067 g, 0.350 mmol), HOBt (0.060 g, 0.420 mmol), and DIEA (0.060 mL, 0.35 mmol) followed by (3-fluorophenyl)methanamine (0.040 g, 0.350 mmol) . The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature, diluted with saturated NaHCO3, and extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with saturated NaCl (3×) and dried (MgSO4), then concentrated and purified by silica gel flash chromatography (1–5% MeOH/DCM) to provide the target compound (0.05 g, 33%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.84–8.89 (m, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.42–7.76 (m, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.6, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.32 (m, 2H), 6.74–7.07 (m, 3H), 6.02–5.97 (s,1H), 4.15–4.39 (q, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 4.02 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 2.96–3.23 (m, 1H), 2.65–2.96 (m, 1H), 1.94–2.17 (m, 6H), 1.54–1.88 (m, 4H), 1.44 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 392.1. HPLC tR = 3.9 min, >95% purity.

N-(3-Fluorobenzyl)-1-(1-(isoquinolin-5-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (4c)

Ethyl 1-(1-(isoquinolin-5-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate 28c (0.50 g, 1.61 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (20 mL), followed by 1 N sodium hydroxide (3.2 mL, 3.2 mmol) in one portion. The resulting mixture was stirred for 18 h at room temperature, concentrated in vacuo, and partitioned between ether and a minimum amount of water. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was treated with AcOH dropwise until the solution measured acidic by pH paper. The solution was concentrated in vacuo, dried under high vacuum, and the resulting carboxylic acid was used without further purification in the next step. To a solution of (R,S)-1-(1-(isoquinolin-5-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylic acid (0.100 g, 0.350 mmol) in dry DMF (5 mL) were added EDCI (0.067 g, 0.350 mmol), HOBt (0.070 g, 0.420 mmol), and DIEA (0.061 mL, 0.352 mmol) followed by (3-fluorophenyl)methanamine (0.044 g, 0.352 mmol). The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature, diluted with saturated NaHCO3, and extracted with EtOAc (2×). The combined organic extracts were washed with saturated NaCl (3×), dried (MgSO4), then purified by silica gel flash chromatography (1–5% MeOH/DCM) to afford the final compound (0.02 g, 16%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 9.19 (s, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 7.62–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.62 (m, 1H), 7.10–7.42 (m, 1H), 6.64–7.10 (m, 3H), 5.98 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 4.02 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 3.14 (m, 1H), 2.56–3.04 (m, 1H), 1.89–2.37 (m, 3H), 1.53–1.89 (m, 3H), 1.42 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 392.1. HPLC tR = 4.0 min, >95% purity.

N-(3-Fluorobenzyl)-1-(1-(isoquinolin-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (4d)

To a solution of 27d (50 mg, 0.16 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) was added NaOH (11 mg, 0.48 mmol), and the mixture was allowed to stir at 50 °C for 6 h. The solution was concentrated in vacuo and acidified with 4 M HCl in dioxane (5 mL). The solution was again concentrated in vacuo and allowed to dry overnight. The crude carboxylic acid was dissolved in DMF (10 mL), and EDCI (49 mg, 0.38 mmol), HOBt (43 mg, 0.32 mmol), DIEA (103 mg, 0.80 mmol), and 3-fluorobenzylamine (24 mg, 0.20 mmol) were added and allowed to stir at 23 °C for 16 h. The reaction was quenched with saturated NaHCO3 (25 mL), washed with H2O (2 × 20 mL), brine (1 × 20 mL), dried (MgSO4), and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (1–4% MeOH/DCM) to furnish the desired material (23 mg, 37.1%) as a dark brown oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.66 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.49 (m, 2H), 7.09–6.96 (m, 2H), 6.92 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 5.81 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.40 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.09 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 2.91 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 2.36–2.26 (m, 1H), 2.18–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.77 (dd, J = 8.5, 3.5 Hz, 3H), 1.53 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 392.2. HPLC tR = 5.2 min, >95% purity.

(R)-1-(1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)-N-(pyridin-3-ylmethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (5a)

Coupling method A: 50% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.48–8.51 (m, 2H), 7.83 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 3H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.47–7.53 (m, 4H), 7.23–7.25 (m, 1H), 6.08 (s, 1H), 4.44–4.45 (m, 2H), 3.26 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 2.11–2.48 (m, 2H), 1.63–2.11 (m, 7H), 1.48 (s, 3m). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 374.2. HPLC tR = 4.6 min, >95% purity.

(R)-1-(1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)-N-(pyridin-4-ylmethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (5b)

Coupling method A: 27% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.51 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 7.79–7.83 (3H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.43–7.54 (m, 3H), 7.13 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 6.06 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.63 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 3.17–3.20 (m, 1H), 2.92- 2.95 (m, 1H), 1.96- 2.16 (m, 4H), 1.65–1.91 (m, 3H), 1.47 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 374.2. HPLC tR = 4.6 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-((2-Methoxypyridin-4-yl)methyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (5c)

Coupling method B: 26% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.38 (br s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.91 (m, 3H), 7.58 (br s, 1H), 7.45 (m, 3H), 6.72 (m, 1H), 6.56 (s, 2H), 5.85 (br s, 1H), 4.36 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.10 (m, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.25 (m, 1H), 2.94 (m, 1H), 1.58–2.15 (m, 5H), 1.41 (m, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 404.1. HPLC tR = 4.5 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(4-Chlorophenethyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (6a)

Coupling method B: 33% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.41 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (dd, J = 7.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (m, 1H), 7.29–7.50 (m, 3H), 7.13–7.33 (m, 3H), 6.86–7.18 (m, 2H), 5.41 (s, 1H), 4.08 (s, 1H), 3.45 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.18 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 2.76–2.98 (m, 1H), 2.38–2.76 (m, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.52–2.16 (m, 7H), 1.45 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 421.1. HPLC tR = 6.0 min, >95% purity.

(R)-N-(3-Fluorophenethyl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (6b)

Coupling method B: 36% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.42 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.77–8.04 (m, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.48–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.32–7.48 (m, 3H), 7.18–7.32 (m, 1H), 6.65–6.99 (m, 3H), 5.42 (s, 1H), 4.08 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.37–3.56 (m, 1H), 3.19 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 2.78–2.90 (m, 1H), 2.77 (s, 1H), 1.87–2.09 (m, 5H), 1.54–1.86 (m, 4H), 1.45 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 405.2. HPLC tR = 5.8 min, >95% purity.

N-(3-Fluorobenzyl)-1-(1,2,3,4-tetrahydrophenanthren-4-yl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (7)

To a solution of 33 (97 mg, 0.23 mmol) in THF/MeOH/H2O (3:1:1) (7 mL) at 0 °C was added LiOH (19 mg, 0.45 mmol), and the mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 16 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, acidified using HCl–dioxane, and crystallized with the addition of EtOAc (5 mL). The product was filtered to furnish the carboxylic acid (65 mg, 70%) as a white solid. This acid was carried forward without purification and was dissolved (63 mg, 0.2 mmol) in dry DMF (5 mL), followed by EDCI (41 mg, 0.27 mmol), HOBt (37 mg, 0.27 mmol), DIEA (133 mg, 1.03 mmol), and 3-fluorobenzylamine (28 mg, 0.23 mmol), and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 16 h. The reaction mixture was then diluted with EtOAc, quenched with saturated NaHCO3, washed with H2O (2 × 10 mL), saturated NaCl (1 × 10 mL), dried (MgSO4), and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by silica gel flash chromatography (40–60% EtOAc/Hex) to furnish 7 (26 mg, 30%) as a dark oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 8.37 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dt, J = 21.1, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (dd, J = 28.2, 8.1 Hz, 3H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 4.46 (t, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.02–2.87 (m, 2H), 2.84–2.74 (m, 1H), 2.58 (ddd, J = 14.2, 9.9, 4.3 Hz, 2H), 2.33 (t, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 2.27–2.14 (m, 1H), 2.08 (ddt, J = 11.7, 8.0, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 2.01–1.91 (m, 1H), 1.85 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 1.74 (dd, J = 10.8, 5.5 Hz, 2H), 1.61 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 1.42–1.30 (m, 1H). TOF ES+ MS: (M + H) 417.2. HPLC tR = 5.7 min, >95% purity.

2-Methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethanone (9c)

2-Methoxyacetonitrile 8c (0.25 mL, 3.33 mmol) was dissolved in a 250 mM solution of naphthalen-1-ylmagnesium bromide (20 mL, 5.0 mmol) in THF and stirred for 14 h at room temperature. 2 M HCl (10 mL) was added, and this was stirred at room temperature for 8 h. At this time, material was extracted with a 1:1 solution EtOAc/Et2O, dried with anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (20 g silica, 5–20% EtOAc/Hex) to give the desired product (118 mg, 18%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.66 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.61–7.55 (m, 1H), 7.53 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 4.74 (s, 2H), 3.57 (s, 3H).

(±)-1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)propan-1-ol (10a)

1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)propan-1-one 9a (100 mg, 0.54 mmol), prepared from nitrile 8a by the literature method,17 was dissolved in anhydrous THF (1 mL) in dry glassware and cooled to −78 °C. LAH (1 M in THF, 0.27 mL, 0.27 mmol) was added dropwise to the solution. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 4 h or until complete by TLC. The reaction was then worked up according to the Fieser method,5 and the resulting precipitate was filtered off. The filtrate was collected and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was then purified by flash chromatography (15 g silica, 20% EtOAc/Hex) to provide the desired product (85 mg, 85%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.13 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.94–7.89 (m, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.47 (m, 3H), 5.44–5.34 (m, 1H), 2.32 (s, 1H), 2.09–2.00 (m, 1H), 1.99–1.89 (m, 1H), 1.06 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H).

(±)-2-Methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethanol (10c)

2-Methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethanone 9c (118 mg, 0.59 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous Et2O (6 mL) in an ice bath, and a 1 M (in THF) solution of LAH (0.59 mL, 0.59 mmol) was added under N2. This was stirred at room temperature for 3 h, at which time the Fieser workup5 was employed. Precipitate was filtered off and the filtrate concentrated in vacuo to give the desired product as an oil (104 mg, 87%) used without further purification. 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.09 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.93–7.89 (m, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.58–7.50 (m, 3H), 5.75 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (dd, J = 10.1, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (dd, J = 9.9, 9.0 Hz, 1H), 3.50 (s, 3H), 3.30 (bs, 1H).

(±)-Ethyl 1-(1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)propyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate (11a)

1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)propan-1-ol 10a (326 mg, 1.75 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (4 mL) at 0 °C with 3 Å molecular sieves. DIEA (0.92 mL, 5.25 mmol) was added, and with continuous stirring at 0 °C, Ms2O (396 mg, 2.27 mmol) was added dropwise. The solution was stirred for 40 min at 0 °C, at which point ethyl piperidine-4-carboxylate (1.62 mL, 10.5 mmol) was added. The mixture was then stirred for 48 h at room temperature. At that time, EtOAc was added and washed with 10% aqueous Na2CO3 (3 × 25 mL). The organic layer was then dried (MgSO4), filtered, and removed in vacuo. Purification was accomplished via flash chromatography (20 g silica, gradient 0–40% EtOAc/Hex) to give the desired product (480 mg, 84%) as a slightly yellow oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.48 (bs, 1H), 7.90–7.86 (m, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.54–7.43 (m, 4H), 4.14 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.94 (bs, 1H), 3.29–3.16 (m, 1H), 2.87–2.75 (m, 1H), 2.27 (tt, J = 11.3, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 2.12–1.93 (m, 5H), 1.85–1.66 (m, 3H), 1.26 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 0.70 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H).

(±)-Ethyl 1-(2-Methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate (11c)

2-Methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethanol 10c (104 mg, 0.51 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (4 mL) at 0 °C, and the following was added sequentially: 3 Å molecular sieves, DIEA (0.27 mL, 1.54 mmol), and Ms2O (116 mg, 0.67 mmol). This was stirred for 40 min at 0 °C, at which time ethyl piperidine-4-carboxylate (0.48 mL, 3.09 mmol) was added. This was stirred for 48 h at room temperature. The material was extracted with EtOAc, and this was washed with 10% Na2CO3 (3 × 25 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (20 g silica, 0–10% EtOAc/Hex gradient) to give the desired product (91 mg, 52%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.41 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92–7.86 (m, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.44 (m, 3H), 4.33–4.19 (m, 1H), 4.15 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (dd, J = 10.3, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (dd, J = 10.3, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 3.32–3.25 (m, 1H), 2.86–2.77 (m, 1H), 2.38–2.23 (m, 2H), 2.14 (t, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 2.03–1.93 (m, 1H), 1.91–1.69 (m, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H).

(±)-1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)ethane-1,2-diol (13)

2-Hydroxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethanone 12 (200 mg, 1.07 mmol), prepared previously by the literature method,18 was dissolved in anhydrous THF (2 mL) and was cooled in an ice bath. 1 M LAH in THF (1.07 mL, 1.07 mmol) was slowly added dropwise to the solution. The mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature and was stirred for 2 h. After this time, the reaction was worked up by the Fieser method,27 the aluminum was filtered off, and the filtrate solvent was removed in vacuo to give a white solid. This was purified by flash chromatography (10 g silica, 50% EtOAc/Hex) to give the desired product (168 mg, 83%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.16 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.48 (m, 3H), 5.44 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (dt, J = 7.7, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.87 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 3.66 (ddd, J = 10.1, 6.0, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.50 (ddd, J = 11.3, 7.4, 5.9 Hz, 1H).

(±)-2-((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethanol (14)