Abstract

Background

The frequent and distressing adverse events (AEs) of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are of major concern in 63-84% of adult patients undergoing thyroidectomy. We conducted this prospective study to compare two prophylactic strategies; sevoflurane combined with ramosetron and propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia in a homogenous group of non-smoking women undergoing total thyroidectomy.

Methods

In the current prospective study, we enrolled a consecutive series of 64 female patients aged between 20 and 65 years with an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status of I or II who were scheduled to undergo elective total thyroidectomy under general anesthesia. Patients were randomized to either the SR (sevoflurane and remifentanil) group or the TIVA group. We evaluated the incidence and severity of PONV, the use of rescue anti-emetics and the severity of pain during the first 24 h after surgery.

Results

There were no significant differences in the proportion of the patients with a complete response and the Rhodes index, including the occurrence score, distress score and experience score, between the two groups. In addition, there were no significant differences in the proportion of the patients who were in need of rescue anti-emetics or analgesics and the VAS scores between the two groups.

Conclusions

In conclusion, TIVA and ramosetron prophylaxis reduced the expected incidence of PONV in women undergoing total thyroidectomy. In addition, there was no significant difference in the efficacy during the first 24 h postoperatively between the two prophylactic regimens.

Keywords: Postoperative nausea and vomiting, Propofol, Ramosetron, Thyroidectomy

Introduction

The frequent and distressing adverse events (AEs) of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are of major concern in 63-84% of adult patients undergoing thyroidectomy [1,2]. It has been reported that the PONV may prolong the recovery room time and a potential hospital stay and lower the degree of patient satisfaction [3]. In patients who are scheduled to undergo thyroidectomy, it is the notable adverse event and poses challenging problems for anesthesiologists because of surgical wound dehiscence or hematoma-induced upper airway obstruction.

After general anesthesia, various factors are involved in the risk of PONV. It would therefore be mandatory to preoperatively estimate it, which is essential for initiating the proper management. It is known that multiple factors are involved in the increased incidence of PONV; these include patient characteristics, anesthetic technique, surgical procedure and postoperative care [3]. Apfel et al. [4] developed a score-based prediction tool to simply assess the risk of developing PONV. It has been considered that the most notable risk factors of developing PONV include female gender, non-smoker, a past history of motion sickness or PONV and the use of postoperative opioids. Patients are evaluated to be at increased risks of developing PONV when they have more than two of four risk factors [4].

Still, controversial opinions exist regarding the optimal strategy for preventing and treating patients with PONV. It is not recommended that global prophylaxis be performed for patients with PONV. But it is a cost effective modality in a high-risk group of patients [5]. Propofol is a rapid-onset and short-acting hypnotic agent, and it has become the popular choice for the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. It is well known that propofol has an antiemetic effect. Therefore, propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) has been reported to be effective to lower the risk of PONV [6]. Ramosetron is a novel type of 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, and it has a higher potency and a longer receptor-antagonizing effect as compared with its predecessors [7]. Moreover, its effectiveness in preventing and treating PONV after various surgeries has been well documented [8,9,10].

Given the above background, we conducted this prospective study to compare two prophylactic strategies: sevoflurane combined with ramosetron and propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia in a homogenous group of non-smoking women undergoing total thyroidectomy.

Materials and Methods

The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our medical institution. All the patients submitted a written informed consent. In the current prospective study, we enrolled a consecutive series of 64 female patients aged between 20 and 65 years with an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status of I or II who were scheduled to undergo elective total thyroidectomy under general anesthesia.

Exclusion criteria for the current study are as follows:

(1) Patients with gastrointestinal disease, a smoking history or a past history of PONV or motion sickness.

(2) Patients with a past history of taking opioid, steroid or antiemetic medication within 24 h before surgery.

Patients were randomized to either the SR (sevoflurane and remifentanil) group or the TIVA group based on the randomization table generated using an Excel (Microsoft corp., Seoul, Korea).

There were no patients who were preoperatively given preanesthetic medications. On reaching an operating room, patients were continuously monitored with electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, noninvasive blood pressure, bispectral index score monitoring and capnography. All the patients breathed 100% oxygen prior to the induction of anesthesia and received a 5 ml/kg fluid load of plasma solution.

In the SR group, remifentanil (1 mg vial; GlaxoSmithKline, Belgium) was administered with the target-controlled infusion (TCI) system based on the Minto pharmacokinetic Mode using a TCI pump (Orchestra®; Fresenius-Vial, Brezins, France) [11]. In the SR group, general anesthesia was induced using 2 mg/kg of propofol (1% Anepol®; Hana Pharm. Co., Ltd., Hwasung, Korea) and remifentanil at a target effect-site concentration (Ce) of 3 ng/ml. After loss of consciousness, tracheal intubation was promoted using 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium. This was followed by the mechanical ventilation with 50% oxygen and air. Thus, attempts were made to maintain the ETCO2 at 35 mmHg. In addition, the anesthesia was maintained using sevoflurane (1.0-3.0 vol%) accompanied by the continuous infusion of remifentanil. Ramosetron (0.3 mg) was administered intravenously before the end of surgery as the sole intraoperative antiemetic. In the TIVA group, infusions of propofol and remifentanil were prepared using Fresofol 2% injection (50 ml vial; Fresenius Kabi, Austria) and Ultiva™ injection (1 mg vial; GlaxoSmithKline, Belgium), respectively. A commercially-available TCI pump (Orchestra® Base Primea; Fresenius Vial, France) was used for the effect-site TCI, and the pumps used for propofol and remifentanil were identical to those used by Marsh et al. [12] and Minto et al. [11], respectively. In the TIVA group, anesthesia was induced with propofol (Ce of 3.5 mg/ml) and remifentanil (Ce of 3 ng/ml) using a TCI device. The drug infusions were continued until the patients became drowsy, and the tracheal intubation was promoted using 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium. The patients were mechanically ventilated with 50% oxygen and air to maintain the ETCO2 at 35 mmHg, and anesthesia was maintained with a continuous infusion of remifentanil and propofol. Before the end of surgery, ketorolac (30 mg) was injected for the postoperative pain control, and neuromuscular relaxation was reversed with 30 µg/kg pyridostigmine and 7 µg/kg glycopyrrolate in all the patients. All the patients were transferred to the postanesthesia care unit after surgery.

We recorded the age, weight, height, amount of intraoperative fluid, total amount of remifentanil, duration of surgery and anesthesia of the procedure. A trained investigator who was blinded to the anesthetic technique used for each patient visited at 1, 6 and 24 hours postoperatively and recorded the incidence and severity of PONV and pain.

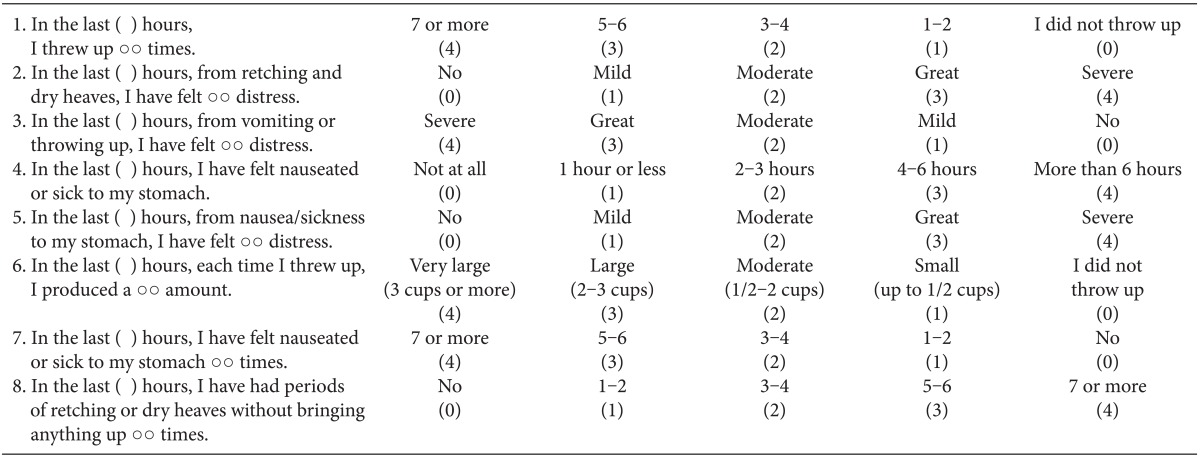

We evaluated all the episodes of PONV (nausea, retching and vomiting) and the severity of PONV using the Rhodes index [13] (Table 1) at the end of each of the following postoperative observation periods: 0-1, 1-6 and 6-24 h. A complete response was defined as no PONV. An intravenous injection of metoclopramide 10 mg was allowed after the patients vomited or when they requested an antiemetic. In addition, the patients received an intravenous injection of dexamethasone 4 mg as a secondline of treatment when they were refractory to metoclopramide. The severity of pain was measured at 1, 6 and 24 h postoperatively with a visual analog scale (VAS). The patients were given ketorolac 30 mg when they were in need of an analgesic. Then, they were given an intravenous injection of pethidine 25 mg as a second-line of treatment when they were refractory to ketorolac.

Table 1.

Rhodes Index of Nausea, Vomiting and Retching (RINVR)

Total experience scores: sum of all scores, total occurrence score: 1 + 4 + 6 + 7 + 8, total distress score: 2 + 3 + 5.

According to previous studies [1,2], the incidence of PONV after thyroidectomy in adult patients is estimated at 70%. We have speculated that it would be clinically significant if there is a 30% reduction in the incidence of PONV in the TIVA group. To verify this, we used type I (α = 0.05, two-sided test) and II errors (β = 0.02, power = 0.8) and estimated the sample size at 28 for each group. In addition, we also assumed a drop-out rate of 10% and thus increased the sample size to 31 for each group. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 15.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). We also performed analysis of variance with Bonferroni's correction, the χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, or the Mann-Whitney U-test, if applicable. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data was expressed as means (SD) or the proportion of patients (%).

Results

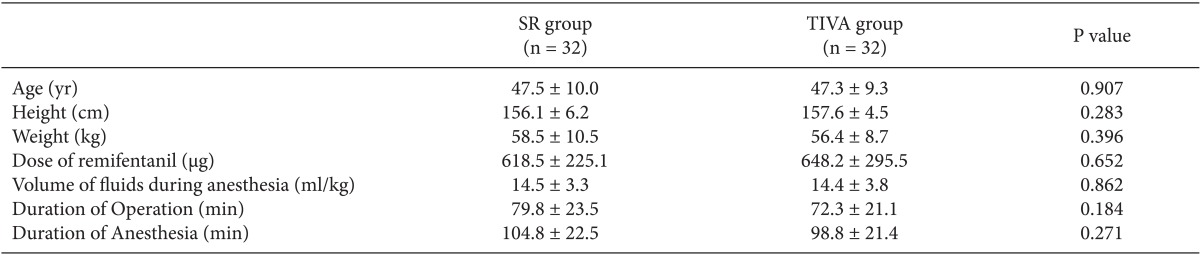

There were no significant differences in the age, body weight, body height, dose of remifentanil, fluid volume during anesthesia and duration of anesthesia and surgery between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

The values are shown as means ± SD or theproportion of patients (%). There were no significant differences in thepatient characteristics between the two groups.

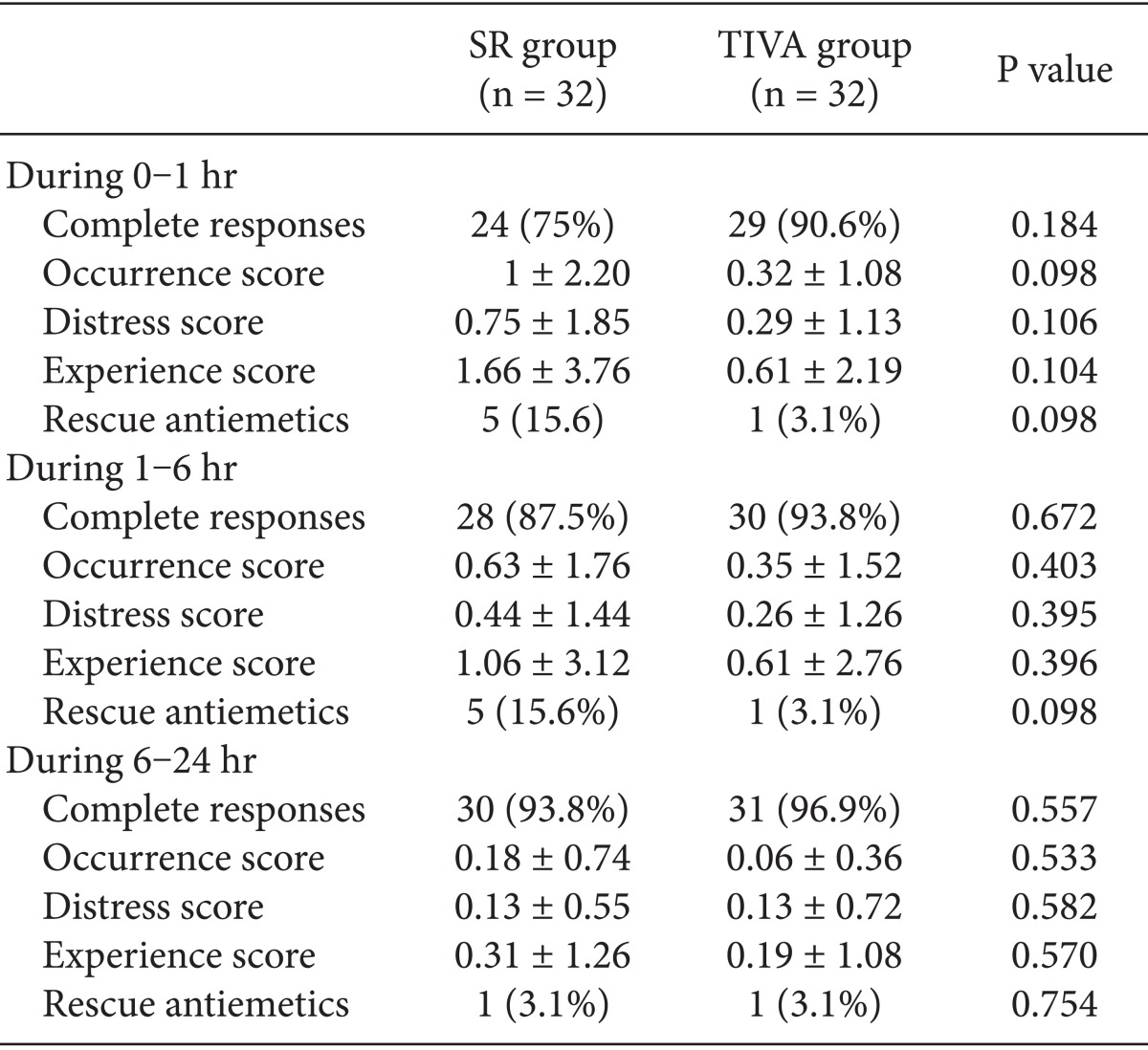

In the TIVA group and the SR group, a complete response was seen at frequencies of 90.6 and 75% during the first 1 h (P = 0.184), 93.8 and 87.5% during the 1 to 6 h (P = 0.672) and 96.9 and 93.8% during the last 6 to 24 h (P = 0.557), respectively (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the proportion of the patients with a complete response and the Rhodes index, including the occurrence score, distress score and experience score, between the two groups.

Table 3.

Rhodes Index of Nausea, Vomiting and Retching (RINVR) and Incidence of Complete Responses

The values are shown as means ± SD or the proportion of patients (%). There were no significant differences in the RINVR and the incidence of complete response between the two groups.

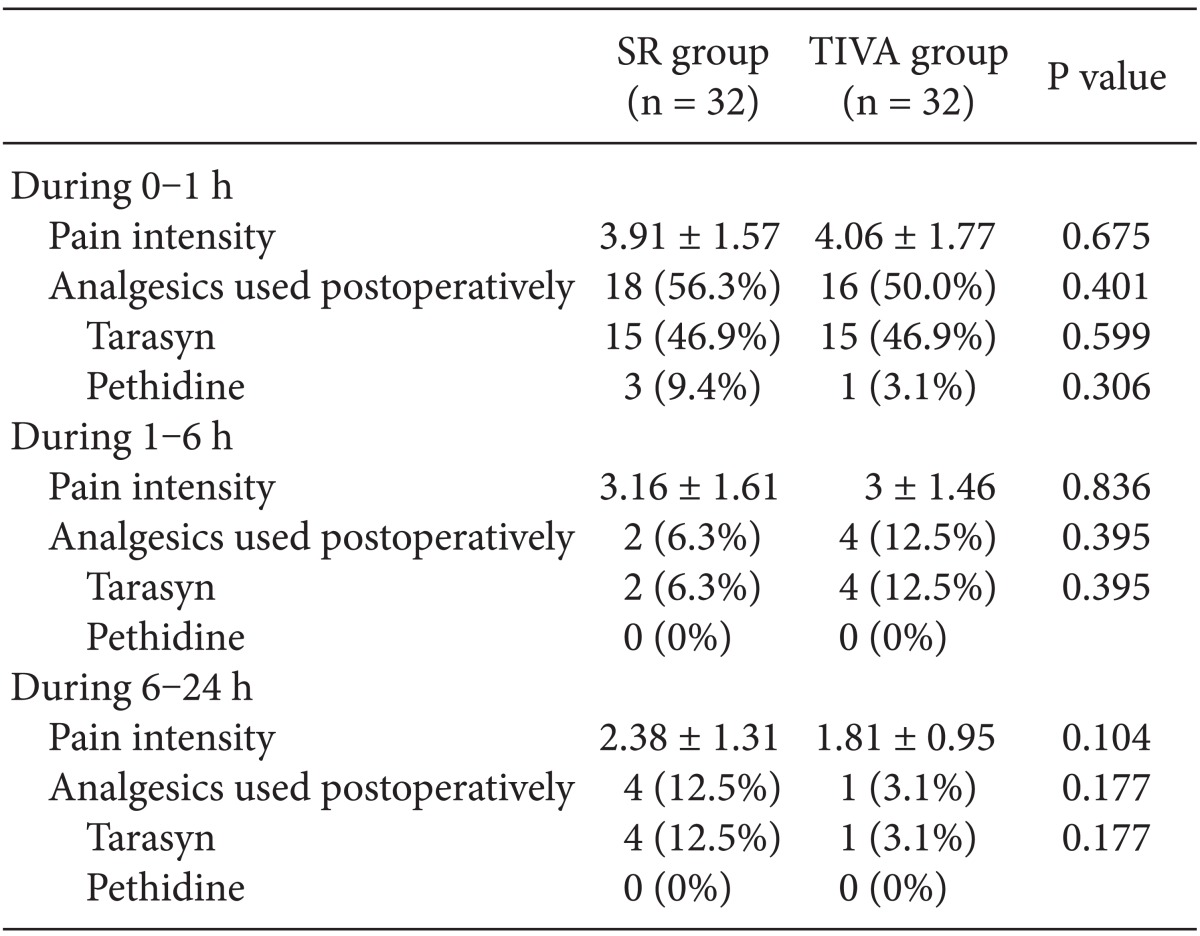

In the TIVA group and the SR group, the proportion of the patients who were in need of rescue anti-emetics was 3.1 and 15.6% during the first 1 h (P = 0.098); 3.1 and 15.6% during the 1 to 6 h (P = 0.098); and 3.1 and 3.1% during the last 6 to 24 h (P = 0.754), respectively (Table 3). But there were no significant differences in the proportion of the patients who were in need of rescue anti-emetics or analgesics and the VAS scores between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Severity of Pain and The Postoperative Analgesics

The values areshown as means ± SD or number of patients. There were no significantdifferences between the two groups.

Discussion

There are numerous published studies and treatment guidelines for PONV. Still, however, it remains one of the most unfavorable complications under general anesthesia. In addition, it commonly decreases the degree of patient satisfaction with postoperative outcomes [14,15]. This is due to many reasons such as a lack of understanding of the underlying mechanisms, the difficulty in estimating the risk of developing PONV in patients, a lack of the anti-emetic intervention as the 'gold-standard' and the variability in the dose-response relationship for current interventions.

To date, a substantial number of studies have examined the effects of numerous anti-emetics including traditional and non-traditional ones and serotonin receptor antagonists in preventing and treating PONV following thyroidectomy. In association with this, it has been previously shown that several serotonin receptor antagonists, such as ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron, dolasetron and ramosetron, are more effective than traditional anti-emetics, including droperidol, metoclopramide and alizapride, in lowering the incidence of PONV after thyroid surgery [16].

Serotonin receptor antagonists bind to the 5-HT3 receptor competitively and selectively in the chemoreceptor trigger zone of the central nervous system and receptors in the gastrointestinal tract, thus being involved in the inhibition of the emetic symptoms [17]. It has also been previously shown that ramosetron had a higher effect in lowering the incidence and severity of nausea and anti-emetic consumption as compared with dexamethasone in patients following thyroidectomy [18]. Moreover, it has also been reported that ramosetron 0.3 mg was effective in lowering the incidence and severity of postoperative nausea in women undergoing total thyroidectomy; this was notable during the first 6 hours postoperatively [19].

There is a growing interest in the anesthetic technique using the TIVA with propofol and remifentanil for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. It has been previously shown not only that the TIVA might be effective in lowering 5-HT3 levels in the area postrema but also that subhypnotic doses of propofol are effective in decreasing the incidence of PONV [20,21]. Previous studies have evaluated the anti-emetic efficacy of propofol in maintaining the anesthesia in patients who are scheduled to undergo thyroidectomy [2,22,23]. Sonner et al. [2] and Jost et al. [22] demonstrated that the incidence of PONV was significantly lower in patients receiving propofol for the maintenance of anesthesia as compared with those doing isoflurane.

In the current study, in the TIVA group and the SR group, a complete response (no PONV, no rescue) was seen at frequencies of 90.6 and 75% during the first 1 h; 93.8 and 87.5% during the 1 to 6 h; and 96.9 and 93.8% during the last 6 to 24 h, respectively. Our results showed that the TIVA and ramosetron prophylaxis reduced the expected rate of PONV in women undergoing total thyroidectomy during the first 24 h postoperatively.

We have speculated that the prophylactic ramosetron is more effective in preventing the occurrence of PONV as compared with TIVA. Our results showed, however, that there was no significant difference in the efficacy during the first 24 h postoperatively between the two prophylactic regimens. Consistent with this, White et al. [24] compared the efficacy in preventing the occurrence of PONV between the two prophylactic strategies, sevoflurane combined with dolasetron and TIVA using propofol and remifentanil, thus reporting that there was no significant difference in the efficacy between the two regimens during the early postoperative period. In addition, it has recently been shown that there was no significant difference in the efficacy in lowering the incidence of PONV after gynecological laparoscopic surgery between prophylactic palonosetron with inhalational anesthesia using sevoflurane in 50% nitrous oxide and propofol-based TIVA during the early and late postoperative period [25]. In contrast, Paech et al. [26] conducted a randomized trial to compare the efficacy between TIVA alone and inhalation anesthesia plus dolasetron in patients undergoing day-case gynecological laparoscopy, thus reporting that there were no significant differences in the proportion of patients who showed a complete response and used the rescue anti-emetics during the postoperative period before discharge between the two groups. According to these authors, however, the incidence of post-discharge nausea was significantly higher in the inhalation anesthesia plus dolasetron group as compared with the TIVA alone group. It is noteworthy that patients of the inhalation anesthesia plus dolasetron received nitrous oxide that potentially made them predisposing to PONV.

Our results showed that many potential factors associated with the incidence of PONV, such as age, smoking status and the type and duration of surgery, were well balanced between the two groups. There are various types of treatment modalities for the prevention of PONV after thyroid surgery, whose benefits and risks have been well documented [16]. Propofol-induced complications have also been described in the literature; these include convulsion, anaphylaxis and life-threatening anaphylactoid reaction [27,28]. It is known that serotonin receptor antagonists are generally well tolerated with few adverse effects. But ramosetron is more expensive than other types of antiemetics such as metoclopramide.

There are several limitation of the current study as shown below:

(1) We failed to enroll a high-risk group of patients with a history of motion sickness or a previous episode of PONV

(2) We failed to evaluate the baseline incidence of PONV by serving the placebo-controlled group because we considered it unethical to withhold prophylactic interventions in patients who were at increased risk of developing PONV. This deserves further studies.

In conclusion, TIVA and ramosetron prophylaxis reduced the expected incidence of PONV in women undergoing total thyroidectomy. In addition, there was no significant difference in the efficacy during the first 24 h postoperatively between the two prophylactic regimens.

References

- 1.Ewalenko P, Janny S, Dejonckheere M, Andry G, Wyns C. Antiemetic effect of subhypnotic doses of propofol after thyroidectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:463–467. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonner JM, Hynson JM, Clark O, Katz JA. Nausea and vomiting following thyroid and parathyroid surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:398–402. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(97)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golembiewski J, Chernin E, Chopra T. Prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1247–1260. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.12.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apfel CC, Kranke P, Eberhart LH. Comparison of surgical site and patient's history with a simplified risk score for the prediction of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:1078–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill RP, Lubarsky DA, Phillips-Bute B, Fortney JT, Creed MR, Glass PS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prophylactic antiemetic therapy ith ondansetron, droperidol, or placebo. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:958–967. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sneyd JR, Carr A, Byrom WD, Bilski AJ. A meta-analysis of nausea and vomiting following maintenance of anaesthesia with propofol or inhalational agents. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1998;15:433–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1998.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang YK, Park YH, Ryoo BY, Bang YJ, Cho KS, Shin DB, et al. Ramosetron for the prevention of cisplatin-induced acute emesis: a prospective randomized comparison with granisetron. J Int Med Res. 2002;30:220–229. doi: 10.1177/147323000203000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SI, Kim SC, Baek YH, Ok SY, Kim SH. Comparison of ramosetron with ondansetron for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing gynaecological surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:549–553. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HJ, Kwon JY, Shin SW, Kim CH, Baek SH, Baik SW, et al. Preoperatively administered ramosetron oral disintegrating tablets for preventing nausea and vomiting associated with patient-controlled analgesia in breast cancer patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25:756–762. doi: 10.1017/S0265021508004262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu J, So YM, Hwang J, Do SH. Ramosetron versus ondansetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:812–817. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minto CF, Schnider TW, Egan TD, Youngs E, Lemmens HJ, Gambus PL, et al. Influence of age and gender on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of remifentanil. I. Model development. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:10–23. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199701000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsh B, White M, Morton N, Kenny GN. Pharmacokinetic model driven infusion of propofol in children. Br J Anaesth. 1991;67:41–48. doi: 10.1093/bja/67.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes VA, McDaniel RW. The Index of Nausea, Vomiting, and Retching: a new format of the Index of Nausea and Vomiting. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–184. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gan TJ, Meyer TA, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Habib AS, et al. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1615–1628. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000295230.55439.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujii Y. The benefits and risks of different therapies in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. Curr Drug Saf. 2008;3:27–34. doi: 10.2174/157488608783333934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunce KT, Tyers MB. The role of 5-HT in postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69(7 Suppl 1):60S–62S. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.60s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song YK, Lee C. Effects of ramosetron and dexamethasone on postoperative nausea, vomiting, pain, and shivering in female patients undergoing thyroid surgery. J Anesth. 2013;27:29–34. doi: 10.1007/s00540-012-1473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee DC, Kwak HJ, Kim HS, Choi SH, Lee JY. The preventative effect of ramosetron on postoperative nausea and vomiting after total thyroidectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;61:154–158. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2011.61.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cechetto DF, Diab T, Gibson CJ, Gelb AW. The effects of propofol in the area postrema of rats. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:934. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200104000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SI, Han TH, Kil HY, Lee JS, Kim SC. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting by continuous infusion of subhypnotic propofol in female patients receiving intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:898–900. doi: 10.1093/bja/85.6.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jost U, Dörsing C, Jahr C, Hirschauer M. Propofol and postoperative nausea and/or vomiting. Anaesthesist. 1997;46:776–782. doi: 10.1007/s001010050468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooker CD, Sutherland J, Cousins MJ. Propofol manitenance to reduce postoperative emesis in thyroidectomy patients: a group sequential comparison with isoflurane/nitrous oxide. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1998;26:625–629. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9802600602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White H, Black RJ, Jones M, Mar Fan GC. Randomized comparison of two anti-emetic strategies in high-risk patients undergoing day-case gynaecological surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98:470–476. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park SK, Cho EJ. A Randomized controlled trial of two different interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: total intravenous anaesthesia using propofol and remifentanil versus prophylactic palonosetron with inhalational anaesthesia using sevoflurane-nitrous oxide. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:1808–1815. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paech MJ, Lee BH, Evans SF. The effect of anaesthetic technique on postoperative nausea and vomiting after day-case gynaecological laparoscopy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2002;30:153–159. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0203000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etchu H, Kurahashi K, Kitamura S. A case of convulsion induced by propofol. Masui. 1998;47:77–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laxenaire MC, Mata-Bermejo E, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Gueant JL. Life threatening anaphylactoid reactions to propofol (Diprivan) Anesthesiology. 1992;77:275–280. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199208000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]