Abstract

Although endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is now accepted for treatment of early gastric cancers (EGC) with negligible risk of lymph node (LN) metastasis, ESD for intramucosal undifferentiated type EGC without ulceration and with diameter ≤ 2 cm is regarded as an investigational treatment according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines. This consideration was largely based on the analysis of surgically resected EGCs that contained undifferentiated type EGCs; however, results from several institutes showed some discrepancies in sample size and incidence of LN metastasis. Recently, some reports about the safety and efficacy of ESD for undifferentiated type EGC meeting the expanded criteria have been published. Nonetheless, only limited data are available regarding long-term outcomes of ESD for EGC with undifferentiated histology so far. At the same time, endoscopists cannot ignore the patients’ desire to guarantee quality of life after the relatively non-invasive endoscopic treatment when compared to conventional surgery. To satisfy the needs of patients and provide solid evidence to support ESD for undifferentiated EGC, we need more delicate tools to predict undetected LN metastasis and more data that can reveal predictive factors for LN metastasis.

Keywords: Early gastric cancer, Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Undifferentiated histology, Indications

Core tip: Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for intramucosal undifferentiated (UD) type early gastric cancer (EGC) without ulceration and with diameter ≤ 2 cm is regarded as an investigational treatment according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines. In contrast, the controversial results about the safety of ESD for UD-EGC fulfilling the criteria have been reported and a little is known about the long-term outcomes. Therefore, in this review, we focused on the safety and therapeutic efficacy of ESD for UD-EGC with reference to risks for lymph node metastasis within the proposed criteria as well as the short-term and long-term outcomes of ESD for UD-EGC.

INTRODUCTION

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as gastric cancer that is confined to the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of the presence of regional lymph node (LN) metastases[1]. In the Eastern hemisphere, up to 70% of all gastric cancers are diagnosed as EGCs (due to mass population screening)[2-4], whereas in the Western hemisphere, the rate of gastric cancers identified as EGCs accounts for only about 15%[5,6]. EGC reveals a favorable prognosis compared with advanced gastric cancer, with 5-year survival rates being in excess of 90% to 95%, based on Korea, Japan, and European data[7-13].

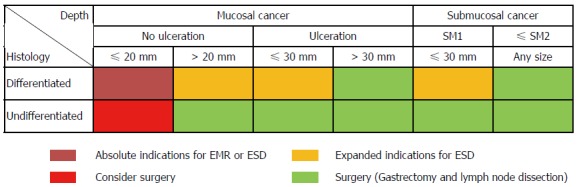

In Eastern countries, endoscopic resection (ER), including endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), has been widely accepted as a minimally invasive treatment for EGC with a negligible risk of LN metastasis[14-18]. Recently, considerable data have also been reported from the Western world as ER is gaining wide acceptance[19-21]. Tumors indicated for ER as a standard treatment are differentiated-type adenocarcinomas without ulceration, of which the depth of invasion is clinically diagnosed as mucosal layer and the diameter is ≤ 20 mm[22]. Gotoda et al[23] studied surgically resected specimens of EGC and suggested the following four expanded indication criteria for endoscopic treatment of EGC without LN metastasis: (1) differentiated intramucosal cancer without ulceration, regardless of size; (2) differentiated intramucosal cancer with ulceration and diameter ≤ 30 mm; (3) differentiated minute submucosal penetrative cancer in diameter ≤ 30 mm; and (4) undifferentiated (UD) type intramucosal cancer without ulceration and diameter ≤ 20 mm. In particular, surgery was still considered in the UD-EGC meeting the expanded criteria because endoscopic en-bloc removal was sometimes difficult in this type of tumors (Figure 1)[24,25]. However, Hirasawa et al[26] added to the body of evidence that there is no LN metastasis in patients with UD-EGC within the expanded criteria. This study revealed the 95%CI of the calculated risk of metastasis to nodes was 0%-0.96%, while the earlier study by Gotoda et al[23] showed that of risk was 0%-2.6% due to small sample size (n = 141), which may potentially be inferior to the outcomes of surgical resection.

Figure 1.

Absolute and expanded indication for endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. SM1: Tumor invasion into the upper third of the submucosa (≤ 500 μm); SM2: Tumor invasion into the mid-third of the submucosa (> 500 μm). EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Along these lines, the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines (2010, ver. 3) state that ER for these UD-EGCs is regarded as an investigational treatment, and that ESD, not EMR, should be employed. In contrast, clinical practice guidelines, according to both National Comprehensive Cancer Network[27] and European Society for Medical Oncology[28], do not yet recognize ER for EGCs meeting the expanded criteria as safe. Moreover, the controversial results about the safety of ESD for UD-EGC fulfilling the criteria have been reported and a little is known about the long-term outcomes. Therefore, in this review, we focused on the safety and therapeutic efficacy of ESD for UD-EGC with reference to risks for LN metastasis within the proposed criteria as well as the short-term and long-term outcomes of it.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT OF LN METASTASIS

The most important factor concerning endoscopic treatment with curative intent is the prediction of regional LN metastasis before treatment[22,27,28]. Reported rates of LN metastasis in EGC range from 5.7% to 20% based on the analysis of surgically resected specimen of EGC[29-34]. UD-EGC demonstrates 4.2% to 4.9% and 19.0% to 23.8%of LN metastasis in the mucosal and submucosal invasive tumors, respectively[23,26]. To date, no imaging modality has been proven to be consistently accurate in assessing LN metastasis in EGC[35,36]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is one of most studied procedures for the locoregional staging of gastric cancer. Reported sensitivities and specificities of EUS to detect LN metastases in gastric cancers varied widely, between 16.7% and 95.3%, and between 48.4% and 100%, respectively[35]. EUS demonstrated a moderate accuracy that seems to describe advanced T stage (T3 and T4) better than N or less advanced T stage[37,38]. Although a clinically relevant benefit of EUS to distinguish intramucosal lesions from submucosal lesions should be further improved[39], EUS is an important imaging modality for preoperative assessment to exclude LN metastasis as well as to confirm deeper wall invasion including the proper muscle layer. Nevertheless, we should consider that UD histology would cause under-diagnosis and affect the accuracy of EUS compared to the differentiated histology[40].

In addition to the diagnostic role of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI) for determining tumor margin in EGC[41,42], ME-NBI has been suggested as a supporting tool for the assessment of invasion depth in EGC[43-46]. In contrast to the usefulness of ME-NBI for evaluating invasive depth in esophageal or colon cancer[47,48], the utility of ME-NBI for determining invasion depth in EGC is not conclusive, because the invasive tumor is often not exposed at the surface and the mucosal structure remains, even when cancer invades the submucosa. Therefore, it is difficult to estimate reliably the depth of invasion by surface appearance[49]. ME-NBI should also distinguish findings suggestive of submucosal invasion from those indicative of the UD histologic type[44,45]. The findings of a nonstructural pattern in the neoplastic lesion of the stomach on ME[45] or no surface pattern and sparse microvessels (markedly distorted, isolated, heterogeneous) or with avascular areas on ME-NBI[44] are indicative of undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma or differentiated cancer with deep submucosal invasion. In contrast, ME-NBI images of UD-EGC were very closely related to the histopathological findings in other study[50], and therefore, this imaging tool can be useful in the pretreatment assessment of the histopathological patterns of cancer development and the lateral extent of UD-EGC. Thus, the role of ME-NBI in differentiation of histologic types in addition to invasive depth should be validated through further prospective studies.

Other imaging modalities including abdominal ultrasound (AUS), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) achieved limited success to stage preoperative LN status[35,36]. A meta-analysis by Seevaratnam et al[36] showed that imaging modalities range in overall accuracy from 53.4% (MRI) to 68.1% (AUS), in sensitivity from 40.3% (PET) to 85.3% (MRI), and in specificity from 75.0% (MRI) to 97.7% (PET), with no significant differences between modalities. To date, there are no clinically relevant imaging tools to detect the submucosal invasion and the LN metastasis in EGC that are critical conditions for determining proper candidates for ER.

RISK FACTORS FOR LN METASTASIS AND PROPOSED CRITERIA FOR ESD

Because currently available imaging modalities fail to accurately evaluate nodal status, endoscopic resectability according to nodal status in EGC and subsequent curability are still determined by means of the presence or absence of certain tumor characteristics which were obtained from the analysis of surgically resected EGC. According to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[22], the main risk factors predictive of LN metastasis in EGC are histologic type, depth of invasion, ulceration, size, and lymphovascular invasion largely based on two large-scale datasets[23,26]. These factors consist of absolute and expanded indications as well as curability of ER with en bloc resection and negative lateral/vertical margin (Table 1)[22,51]. A meta-analysis by Kwee et al[52] identified the characteristics related to LN metastasis in EGC, including age, gender, location, size, macroscopic type, ulceration, histologic type in accordance with Japanese and Lauren classification, lymphovascular invasion, submucosal vascularity, a proliferating cell nuclear antigen labeling index, a matrix metalloproteinase-9-positivity, a gastric mucin phenotype, and a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-positivity. These factors revealed partially different correlations with LN metastasis in intramucosal and submucosal EGCs, respectively.

Table 1.

Curability for endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer

| Curability criteria | |

| Curative resection | En bloc resection, no lateral and vertical margin positivity, no lymphovascular invasion |

| Intramucosal cancer, differentiated histology, size ≤ 20 mm, No ulcerative finding | |

| Curative resection for expanded indications | En bloc resection, no lateral and vertical margin positivity, no lymphovascular invasion |

| Intramucosal cancer, differentiated histology, size > 20 mm, no ulcerative finding | |

| Intramucosal cancer, differentiated histology, size ≤ 30 mm, presence of ulcerative finding | |

| SM 1 depth of invasion, differentiated histology, size ≤ 30 mm, no ulcerative finding | |

| Intramucosal cancer, undifferentiated histology, size ≤ 20 mm, no ulcerative finding | |

| Non-curative resection | Any resection that does not satisfy one of the above criteria |

SM: Submucosa.

With regard to LN metastasis particularly in UD-EGC, many recent studies investigated the risk factors and suggested their criteria for ER of UD-EGC (Table 2)[23,26,53-65]. The overall rates of LN metastasis in UD-EGC varied from 7.9% to 24.5%; however, the heterogeneous composition in subtypes of UD histology in lesions from 15 studies should be taken into account.

Table 2.

Proposed criteria for endoscopic resection of undifferentiated type early gastric cancer

| Study | Year | Country | No. of patients with UD-EGC | No. of patients with PD/SRC/MC | LNM in UD-EGC, n (%) | LNM in proposed criteria | Risk factors related to LNM in UD-EGC |

Proposed criteria of ER for UD-EGC |

|||

| Size, mm | Depth of invasion | Ulcer | LVI | ||||||||

| Tong et al[53] | 2011 | China | 193 | 81/102/7/31 | 46 (23.8) | 0/72 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI, Histologic type | NS or ≤ 20 | M or SM | NS | No |

| Kim et al[54] | 2011 | South Korea | 707 | 288/419/0 | 65 (9.2) | 0/101 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI, Age2 | 153 | M | NS | No |

| Li et al[55] | 2010 | China | 108 | 85/16/7 | 16 (14.8) | 0/25 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI | 20 | M | NS | No |

| Park et al[56] | 2009 | South Korea | 215 | Only SRC | 17 (7.9) | 0/57 | Depth of invasion, LVI | 25 | SM2 | NS | No |

| Kunisaki et al[57] | 2009 | Japan | 573 | 182/378/13 | 74 (12.9) | 0/85 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI | 20 | M | NS | No |

| Hirasawa et al[26] | 2009 | Japan | 3843 | NA | 504 (13.1) | 0/310 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI | 20 | M | No | No |

| Hanaoka et al[58] | 2009 | Japan | 143 | NA | 35 (24.5) | 0/41 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI, Histologic type | 30 | ≤ 500 μm4 | NS | No5 |

| Ye et al[59] | 2008 | South Korea | 591 | 266/316/9 | 79 (13.4) | 0/119 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI | 25 | M | NS | No |

| Park et al[60] | 2008 | South Korea | 234 | Only PD | 25 (21.6) | 0/56 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI | 15 | M or ≤ 500 μm | NS | No |

| Li et al[61] | 2008 | China | 85 | Only PD | 12 (14.1) | 0/25 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI | 20 | M | NS | No |

| Li et al[62] | 2008 | South Korea | 646 | 307/330/9 | 61 (9.4) | 1/201 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI | 20 | M | NS | No |

| Ha et al[63] | 2008 | South Korea | 641 | 248/388/5 | 100 (15.6) | 0/77 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI, histologic type | 20 | M | NS | No |

| Hyung et al[64] | 2004 | South Korea | 289 | NA | 43 (14.9) | NA | Size, depth of invasion, LVI, histologic type | 15 | M | NS | No |

| Abe et al[65] | 2004 | Japan | 175 | 68/104/3 | 32 (18.3) | 0/6 | Size, LVI | 10 | M | NS | No |

| Gotoda et al[23] | 2000 | Japan | 2341 | NA | 243 (10.4) | 0/141 | Size, depth of invasion, LVI, histologic type, ulcer, macroscopic type | 20 | M | No | No |

Three patients had EGCs with histology of undifferentiated adenocarcinoma;

Young age less than 45 years was related to the lymph node metastasis of only poorly-differentiated carcinoma;

Size criteria were ≤ 25 mm in poorly-differentiated adenocarcinomas and ≤ 15 mm in signet-ring cell carcinomas, respectively;

The depth of invasion in proposed criteria was ≤ 500 μm or no more from the lower margin of the muscularis mucosae;

Hanaoka et al also suggested the proportion of undifferentiated components < 50% as one of criteria. UD-EGC: Undifferentiated type early gastric cancer; PD: Poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma; SRC: Signet-ring cell carcinoma; MC: Mucinous carcinoma; LNM: Lymph node metastasis; ER: Endoscopic resection; LVI: Lymphovascular invasion; M: Mucosa; SM: Submucosa; NS: Not significant; NA: Not available.

Size of lesion

Although the intramucosal lesions without ulceration and diameter ≤ 20 mm have been considered as rational criteria for ESD in UD-EGC by Japanese researchers[23,26], different ER criteria have also been suggested with various standards in size, depth of invasion, and presence of ulcerative finding[53-65]. Concerning lesion size, a majority of recent studies (11/15, 73.3%) suggested that a diameter of 20 mm to 30 mm would be the upper limit of the size criterion for UD-EGC to be amenable to treatment with ESD; however, the remaining four studies proposed a diameter of 10 or 15 mm as the upper limit of the criterion, based on their results suggesting the possibility of LN metastasis even in smaller UD-EGC[54,60,64,65]. Debates over the size criterion were highlighted by several reports of LN metastasis of UD-EGCs within the expanded criteria, including a diameter ≤ 20 mm[31,66-70]. Moreover, the size discrepancy between pathologic size and endoscopic size should be resolved, because we can only determine the indications of ER based on the endoscopically estimated size. While a previous study revealed that endoscopic visual estimation method was found to show reliable agreement with pathologic measurements in EGC treated with ER[71], other earlier ESD series showed the mean size discrepancies ranged from 5.8 mm to 6.8 mm, which are not negligible in ER for EGC[72,73]. In UD-EGC, the margins of the lesion tend to be obscured compared to the differentiated histology, which was found to cause frequent margin failure of ESD in our previous report[74]. Thus, a standard reliable measurement method is required through further prospective studies[75].

Submucosal invasion

Some studies suggest that a shallow submucosal invasion is an acceptable depth of invasion in ESD for UD-EGC[53,56,58,60]. However, this suggestion should be reserved until EUS is more reliable for determination of invasive depth, because there is a high chance of endosonographically underestimated depth of invasion and subsequently higher vertical margin positivity in poorly-differentiated EGC[40,74], in addition to the difficult assessment of depth of invasion in UD-EGC[76-79]. Additionally, the numbers of enrolled UD-EGCs in these studies, suggesting a minute submucosal invasion as a criterion for ER, were relatively small compared with other studies. More importantly, the majority of recent studies reported the LN metastasis in a depth of submucosal invasion[23,26,54,55,57,59,61-65].

Ulceration

Ulceration within the lesion is the representative finding with heterogeneity. More than moderate heterogeneity was identified at previous meta-analysis with possible explanation for this heterogeneity due to the interobserver variability between studies for the assessment of tumor ulcerations[52]. Furthermore, this may be due to the different definitions in addition to the interobserver variability for the assessment of ulcerations[52,67,75,80]. Though most of the recent studies (13/15, 86.7%) did not consider the ulcer finding in their proposed criteria, patients with tumor ulcerations had a significantly higher risk of LN metastasis in intramucosal EGC irrespective of histological type at meta-analysis[52]. And ulcerous change decreases the accuracy of EUS diagnosis for the invasive depth of EGC[81]. Therefore, we do not consider ER for UD-EGCs with ulceration as safe.

Lymphovascular invasion

Only the absence of lymphovascular invasion was the criterion included by all studies, which was consistent with the results of a meta-analysis revealing that lymphatic tumor invasion is the strongest predictor for LN metastasis in both mucosal and submucosal gastric cancer[52]. For this reason, EGCs with lymphovascular invasion in endoscopically resected specimen should be treated by further surgery[22]. However, the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines are not based on the status of lymphovascular invasion. The lymphovascular invasion is involved in the decision of curability of ER, since its evaluation can only be available in specimens obtained by ER. Moreover, the determination of lymphovascular invasion sometimes lacks objectivity possibly because of the inability to distinguish lymphatics from blood vessels on conventional hematoxylin-eosin staining[82]. Several studies suggested an endoscopic elevated macroscopic type[83] and a stromal cell-derived factor-1α as risk factors of lymphovascular invasion[84] with reports of usefulness of immunohistochemical staining for detection[82,85,86]. Considering the importance of lymphovascular invasion for prediction of LN metastasis, prospective studies of preoperative prediction for lymphovascular invasion are warranted.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Clinical characteristics of recent representative studies on ER for UD-EGC are summarized in Table 3[73,74,76,80,87-90]. All eight studies were analyzed retrospectively. The numbers of lesions ranged from 46 to 103 lesions and were not large enough to elicit conclusive results. Six studies performed solely ESD[73,76,80,87,89,90] and the rest carried out both EMR and ESD[74,88]. Inclusion criteria of these studies were based on the expanded criteria except those of two studies by Kim et al[80] and Kang et al[73]. The study by Kim et al[80] included patients who refused surgery and were treated by ESD as an experimental treatment. The study by Kang et al[73] included patients with UD-EGC with ulceration. Submucosal invasion and ulcers were noted in 9.7%-19.6% and 1.0%-9.3% of lesions satisfying the expanded criteria, respectively. The two studies that included patients who refused surgery and lesions with ulcerations in endoscopic finding showed relatively high submucosal invasion and ulceration rates. The inaccurate endoscopic size estimation in UD-EGCs is well noted in the studies, because the lesions with size > 20 mm were noted in up to 45.5% of lesions[88]. Particularly, the study including intramucosal UD-EGC with size ≤ 20 mm regardless of ulcerations revealed notably higher SM invasion (28.3%), ulcer finding (28.3%), and size > 20 mm (51.7%) rates[73]. The overall inaccuracies of assessment of depth of invasion, ulcerative findings, and size of UD-EGC tumors fulfilling the expanded criteria are not negligible, and thus ESD criteria based on endoscopic and histologic findings in UD-EGC should have more restrictions compared to differentiated EGC. To overcome this limitation, new methods beyond the current level of technology are strongly needed.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of representative studies on endoscopic resection for undifferentiated type early gastric cancer

| Study | Year | Country | No. of patients with UD-EGC | No. of patients with PD/SRC | Age (yr)1 | Sex (male) | SM invasion | Ulcer | Size (mm)1 | Size > 20 mm |

| Kim et al[80] | 2013 | South Korea | 74 | 55/19 | 61.8 ± 12.0 | 40 (54.1) | 16 (21.6) | 11 (14.9) | 19.9 ± 12.5 | 36 (48.6) |

| Abe et al[87] | 2013 | Japan | 97 | 18/77/22 | 62.0 (35.0-88.0)3 | 55 (56.7) | 19 (19.6) | 9 (9.3) | 12.03 | 14 (14.4) |

| Park et al[88] | 2012 | South Korea | 77 | 47/154 | 60.9 (33.0-82.0) | 49 (63.6) | 12 (15.6) | 4 (5.2) | 23.3 ± 14.0 | 35 (45.5) |

| Okada et al[89] | 2012 | Japan | 1035 | 12/91 | 59.0 (34.0-91.0) | 48 (46.6) | 10 (9.7) | 1 (1.0) | 8.0 (1.0-33.0)3 | NA |

| Kamada et al[76] | 2012 | Japan | 46 | NA | 65.5 (29.0-90.0) | 24 (52.2) | 7 (15.2) | 1 (2.2) | NA | 8 (17.4) |

| Yamamoto et al[90] | 2010 | Japan | 58 | 48/10 | 64.0 (33.0-81.0) | 31 (53.4) | 7 (12.1) | 2 (3.4) | 11.0 (2.0-28.0) | 5 (8.6) |

| Kang et al[73] | 2010 | South Korea | 60 | 30/30 | 56.7 ± 10.4 | 31 (51.7) | 17 (28.3) | 17 (28.3) | 26.3 ± 12.9 | 31 (51.7) |

| Kim et al[74] | 2009 | South Korea | 58 | 17/41 | 55.0 (26.0-81.0) | 26 (44.8) | NA | 0 (0) | 13.3 ± 6.5 | 4 (6.9) |

Data are expressed as absolute numbers (percentage) or mean ± SD.

Data are expressed as mean with standard deviation or range;

Two patients had EGCs with histology of moderately to poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma;

Data are expressed as median with or without range;

Fifteen patients had EGCs with mixed type histology;

A total of 103 EGCs in 101 patients were enrolled. UD-EGC: Undifferentiated typr early gastric cancer; PD: Poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma; SRC: Signet-ring cell carcinoma; SM: Submucosa; NA: Not available.

SHORT-TERM OUTCOMES

In addition to a very low possibility of LN metastasis, the safety of ESD for UD-EGC can be established based on the feasibility of curative resection with acceptable complication rates and consequently favorable long-term outcomes.

Short-term outcomes, including en bloc resection, complete resection, curative resection, and complication rates, of ER for UD-EGC are listed in Table 4[73,74,76,80,87-90]. Whereas homogeneous definitions of en bloc resection applied for the studies, the definitions of complete resection category were heterogeneous depending on the involvement of en bloc resection or lymphovascular invasion or submucosal invasion[73,74,80,87,90]. Additionally, the definitions of curative resection in some studies did not clarify the involvement of en bloc resection[80,89,90]. The overall rates of en bloc resection, complete resection, and curative resection of ER for UD-EGCs varied from 83.1% to 100%, from 55.0% to 90.7%, and from 31.1% to 82.5%, respectively, while those of ESD for UD-EGCs meeting the expanded criteria ranged from 91.3% to 99.0%, from 89.7% to 90.7%, and from 63.9% to 82.5%, respectively[76,87,89,90]. The results of ESD for cases within the expanded criteria were comparable with the outcomes of ESD for differentiated EGCs fulfilling the criteria of 93.0% to 95.7% and 81.0% to 91.1% for en bloc and complete resection rates, respectively[91-93]. In contrast, the curative resection rate seems to be lower than that of differentiated EGCs, which is 91.1%[93]. This may arise from less accurate endoscopic size estimation in UD-EGC due to an ill-defined margin of tumor infiltration[41,94,95] and several distinct features of UD-EGC, including a larger size and submucosal infiltration that can lead to higher rates of lymphovascular invasion[73,82,90,96-98], compared with EGCs with differentiated histology. Therefore, the achievement of reasonable curative resection rate in ESD for UD-EGC is critical by means of more precisely defining of curable lesions.

Table 4.

Short-term outcomes of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated early gastric cancer n (%)

| Study | LMP | VMP | LVI | En bloc resection | Complete resection | Curative resection | OP after ER1 | Residual tumor2 | LNM2 | Bleeding | Perforation |

| Kim et al[80] | NA | NA | 10 (12.5) | 67 (90.5) | 54 (73.0) | 23 (31.1) | 19/51 (37.3) | NA | NA | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.1) |

| Abe et al[87] | 5 (5.2) | 4 (4.1) | 3 (3.1) | 96 (99.0) | 88 (90.7) | 62 (63.9) | 21/35 (60.0) | 1/21 (4.8) | 2/21 (9.5) | 4 (4.1) | 4 (4.1) |

| Park et al[88] | 12 (15.6)3 | 5 (6.5) | 64 (83.1) | NA | 35 (45.5) | 11/42 (26.2) | NA | 0/11 (0.0) | NA | NA | |

| Okada et al[89] | 5 (4.9)3 | 2 (2.0) | 102 (99.0) | NA | 85 (82.5) | 10/18 (55.6) | 2/10 (20.0) | 0/10 (0.0) | 9 (8.7) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Kamada et al[76] | 5 (10.9) | 4 (8.7) | 4 (8.7) | 42 (91.3) | NA | NA | 5 | 1/5 (20.0) | NA | 2/46 (4.3 | 2 (4.3) |

| Yamamoto et al[90] | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.4) | 57 (98.3) | 52 (89.7) | 46 (79.3) | 8/12 (66.7) | 2/8 (25.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | 5 (8.6) | 2 (3.4) |

| Kang et al[73] | 14 (23.3) | 11 (18.3) | 15 (25.0) | 60 (100) | 33 (55.0) | NA | 15/27 (55.6) | 6/15 (40.0) | 2/15 (13.3) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7 |

| Kim et al[74] | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | NA | 49 (84.5) | 39 (67.2) | NA | 9/19 (47.4) | 4/9 (44.4) | 1/9 (11.1) | 8 (13.8) | 1 (1.7) |

Proportions are ratio of additional operation to incomplete or non-curative endoscopic resection;

Data are the incidence of residual tumor or lymph node metastasis in specimens obtained by additional operation;

Data are cases with lateral and/or vertical margin positivity. LMP: Lateral margin positivity; VMP: Vertical margin positivity; LVI: Lymphovascular invasion; OP: Operation; ER: Endoscopic resection; LNM: Lymph node metastasis; NA: Not available.

Further surgical treatments were performed in 26.2% to 60.0% of patients with incomplete or non-curative ER. The presence of residual tumor and LN metastasis in surgical specimens after incomplete or non-curative ER were detected in 4.8% to 44.4% and 0% to 13.3% of cases. The overall rates of bleeding and perforation varied from 1.4% to 13.8% and from 1.0% to 4.3%, respectively, whereas those of ESD for UD-EGCs meeting the expanded criteria ranged from 4.1% to 8.7% and from 1.0% to 4.3%, respectively. The results from lesions within the criteria were comparable with the bleeding and perforation rates of ESD for differentiated EGCs fulfilling the criteria, which were 2.1% to 4.9% and 2.4% to 6.6%, respectively[91-93]. In terms of procedure-related complications, ESD for UD-EGC appears not to be inferior to ESD for EGC with differentiated histology.

LONG-TERM OUTCOMES

Only limited data are available regarding long-term outcomes of ESD for UD-EGC[51,80,87,89], although the recurrences after ER have been shown in 0% to 6.9% with follow-up durations ranging from 16 to 45.6 mo[73,74,76,88,90]. Okada et al[89] reported the first study regarding long-term outcomes of ESD for UD-EGC with limited median follow-up periods. The 5-year cause-specific survival rate among 78 patients with curative resection of UD-EGC was 100%, which was as high as the reported data for gastrectomy[99,100]; however, the median follow-up period was only 36 mo. The cumulative 3- and 5-year disease-free survival rates are 96.7% (95%CI: 92.0%-100%) and 96.7% (95%CI: 92.0%-100%), respectively. During the follow-up period, all patients survived, and no cases of local recurrence and/or distant metastasis were observed. There were only second ESDs for one synchronous lesion of one patient 6 mo after the primary ESD (1/78, 1.3%) and two metachronous lesions of another patient after 23 mo (1/78, 1.3%).

Abe et al[87] analyzed the overall 5-year survival of 79 UD-EGC patients that underwent ESD, while they enrolled 97 patients for short-term outcomes analyses. Of the 46/79 patients in the long-term outcome group who had curative resection, none had local recurrence or LN or distant metastasis, and none died of gastric cancer during a median follow-up of 76.4 mo. The 5-year overall survival rate after curative resection was 93.0%, and no patient died of gastric cancer. These favorable results are comparable to long-term outcomes of those who underwent ESD for differentiated EGC and surgery for intramucosal gastric cancer, which have the overall survival rates of 92.4% to 97.1%[101-103] and 93.5%[104], respectively. The 5-year cumulative incidence of metachronous gastric cancer was 11.4% in the patients with curative resection and they were treated with ESD.

Kim et al[80] reported consistent results showing a local recurrence rate of 5.5% and a 5-year overall survival rate of 93.7% among 74 enrolled patients with median follow-up period of 34 mo (range 7-81 mo). All 4 recurred lesions did not meet the expanded indications and all underwent noncurative resection. There was no mortality related to ESD for treatment of EGC during follow-up, whereas a total of five patients died after ESD due to underlying diseases (four patients) and lung metastasis (one patient).

The questionnaire study on long-term outcomes of curative ESD for EGC at six Japanese institutions with follow-up rates of at least 90% over a minimum 5-year period was reported by Oda et al[51]. Of a total of 1289 patients with curative resections for the expanded indications, the long-term outcomes of 58 patients with intramucosal UD-EGC ≤ 20 mm in size without ulcerations were analyzed, and 96.6% of them (56/58) were followed up for at least 5 years. The overall mortality rate was 10.7% (6/56), and there was no local recurrence, or distant metastasis, or gastric cancer-related death during their long-term follow-up periods.

In addition to the 5-year survival outcomes, the long-term data on metachronous EGCs after ESD for UD-EGC are also lacking. The cumulative incidences of metachronous lesions varied from 1.3% to 11.4% during median follow-up periods with a range of 36-76.4 mo[87-89]. This finding is comparable to the annual incidences of metachronous lesions after ESD for differentiated EGC, which ranged from 1.9% to 3.9%[105,106] as well as reports of remnant gastric cancers occurring in 1.8% to 5% of patients who have had surgical treatment for gastric cancer[107,108]. Therefore, careful periodic endoscopic surveillance should be performed, because UD histology is a possible risk factor associated with the occurrence of metachronous lesions after ER[109]. Although the clinical importance of scheduled endoscopic surveillance after curative resection are recently evaluated through large-volume multicenter study[110], further studies on surveillance follow-up after curative ESD for UD-EGC, compared with curative cases in differentiated EGC, are warranted.

PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE

A combination of laparoscopic sentinel node biopsy and ESD for UE-EGC is an attractive option as a novel, whole stomach-preserved, minimally invasive approach with histological confirmation of LN metastasis. However, a number of technical controversies should be resolved to accept the laparoscopic sentinel node mapping and consequent intraoperative ESD as an acceptable treatment. These include the accuracy of intraoperative pathological diagnosis, the necessity of full-thickness resection, and the possibility of cancer cells being present in afferent lymphatic vessels leading to sentinel nodes[111]. In particular, a well-designed, multicenter feasibility study of laparoscopic sentinel node mapping and biopsy for UD-EGC should be conducted, though the accuracy of determining LN status by laparoscopic sentinel node biopsy is generally acceptable in cases with EGC[112-114].

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) is another promising area to supplement ESD by providing for the means for performing secure gastric closure at the time of the accidental perforation without recourse to surgical operation, or as a complement for endoscopic sentinel node biopsy[115-117]. The potential indications of NOTES have been suggested with a wide spectrum of upper gastrointestinal diseases, including submucosal malignancy and morbid obesity in female patients[118-120]. Furthermore, the first prospective study of 14 patients with EGC who had a risk for LN metastasis and who were treated by hybrid NOTES was reported and suggested that hybrid NOTES may be useful as a bridge between ER and laparoscopic surgery[121]. Nevertheless, given the relatively technical complexity and limits, NOTES has not been proven to remarkably superior to laparoscopic means so far.

CONCLUSION

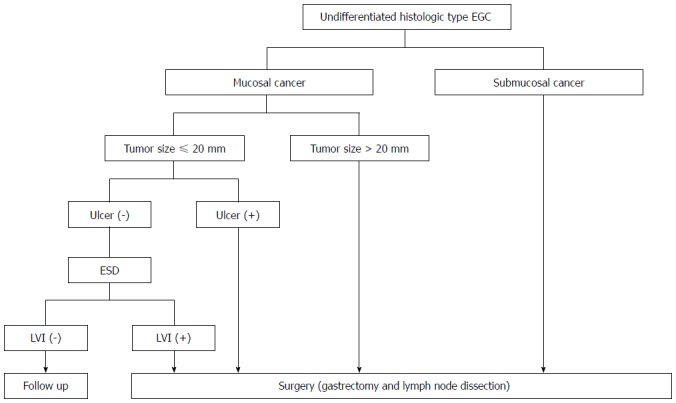

Based on the results of studies on short- and long-term outcomes, the expanded criteria for ESD of UD-EGC are feasible with reference to therapeutic efficacy and safety in the long-term period if curative resection is accomplished, although more long-term outcomes are needed. We now suggest the treatment algorithm for UD-EGC according to depth of invasion, tumor size, ulceration, and lymphovascular invasion (Figure 2). This is consistent with the conditions of curative resection according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[23,26]. However, we should recognize the limitation of current diagnostic and histological tools to predict LN metastasis. The innovative improvement of preoperative imaging modalities and well-defined criteria predictive of LN metastasis from multicenter, prospective studies would reduce the limitation.

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm for undifferentiated type early gastric cancer according to depth of invasion, tumor size, ulceration, and lymphovascular invasion. EGC: Early gastric cancer; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; LVI: Lymphovascular invasion.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Espinel J, Fujisaki J, Manner H, Neesse A S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn YO, Park BJ, Yoo KY, Kim NK, Heo DS, Lee JK, Ahn HS, Kang DH, Kim H, Lee MS. Incidence estimation of stomach cancer among Koreans. J Korean Med Sci. 1991;6:7–14. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1991.6.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura K, Ueyama T, Yao T, Xuan ZX, Ambe K, Adachi Y, Yakeishi Y, Matsukuma A, Enjoji M. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma. Findings in 10,000 patients who underwent primary gastrectomy. Cancer. 1992;70:1030–1037. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920901)70:5<1030::aid-cncr2820700504>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu S, Tada M, Kawai K. Early gastric cancer: its surveillance and natural course. Endoscopy. 1995;27:27–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siewert JR. Gastric cancer: the dispute between East and West. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:59–61. doi: 10.1007/s10120-005-0323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everett SM, Axon AT. Early gastric cancer in Europe. Gut. 1997;41:142–150. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamura T, Tsujitani S, Korenaga D, Haraguchi M, Baba H, Hiramoto Y, Sugimachi K. Lymphadenectomy for cure in patients with early gastric cancer and lymph node metastasis. Am J Surg. 1988;155:476–480. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noguchi Y, Imada T, Matsumoto A, Coit DG, Brennan MF. Radical surgery for gastric cancer. A review of the Japanese experience. Cancer. 1989;64:2053–2062. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891115)64:10<2053::aid-cncr2820641014>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sue-Ling HM, Martin I, Griffith J, Ward DC, Quirke P, Dixon MF, Axon AT, McMahon MJ, Johnston D. Early gastric cancer: 46 cases treated in one surgical department. Gut. 1992;33:1318–1322. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.10.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sue-Ling HM, Johnston D, Martin IG, Dixon MF, Lansdown MR, McMahon MJ, Axon AT. Gastric cancer: a curable disease in Britain. BMJ. 1993;307:591–596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6904.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sano T, Sasako M, Kinoshita T, Maruyama K. Recurrence of early gastric cancer. Follow-up of 1475 patients and review of the Japanese literature. Cancer. 1993;72:3174–3178. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931201)72:11<3174::aid-cncr2820721107>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park CH, Song KY, Kim SN. Treatment results for gastric cancer surgery: 12 years’ experience at a single institute in Korea. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kojima T, Parra-Blanco A, Takahashi H, Fujita R. Outcome of endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: review of the Japanese literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:550–54; discussion 550-54. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tada M, Murakami A, Karita M, Yanai H, Okita K. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 1993;25:445–450. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirao M, Masuda K, Asanuma T, Naka H, Noda K, Matsuura K, Yamaguchi O, Ueda N. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer and other tumors with local injection of hypertonic saline-epinephrine. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:264–269. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(88)71327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotoda T, Kondo H, Ono H, Saito Y, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Yokota T. A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:560–563. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Boku N, Ohtu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. New endoscopic treatment for intramucosal gastric tumors using an insulated-tip diathermic knife. Endoscopy. 2001;33:221–226. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, Kim JJ. Endoscopic mucosal resection of early gastric cancer: Experiences in Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3657–3661. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Probst A, Pommer B, Golger D, Anthuber M, Arnholdt H, Messmann H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric neoplasia - experience from a European center. Endoscopy. 2010;42:1037–1044. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribeiro-Mourão F, Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric lesions: results of an European inquiry. Endoscopy. 2010;42:814–819. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farhat S, Chaussade S, Ponchon T, Coumaros D, Charachon A, Barrioz T, Koch S, Houcke P, Cellier C, Heresbach D, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in a European setting. A multi-institutional report of a technique in development. Endoscopy. 2011;43:664–670. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–225. doi: 10.1007/pl00011720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gotoda T. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4490–4498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.19.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirasawa T, Gotoda T, Miyata S, Kato Y, Shimoda T, Taniguchi H, Fujisaki J, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:148–152. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0515-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ajani JA, Bentrem DJ, Besh S, D’Amico TA, Das P, Denlinger C, Fakih MG, Fuchs CS, Gerdes H, Glasgow RE, et al. Gastric cancer, version 2.2013: featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:531–546. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okines A, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v50–v54. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guadagni S, Reed PI, Johnston BJ, De Bernardinis G, Catarci M, Valenti M, di Orio F, Carboni M. Early gastric cancer: follow-up after gastrectomy in 159 patients. Br J Surg. 1993;80:325–328. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi HJ, Kim YK, Kim YH, Kim SS, Hong SH. Occurrence and prognostic implications of micrometastases in lymph nodes from patients with submucosal gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:13–19. doi: 10.1245/aso.2002.9.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seto Y, Shimoyama S, Kitayama J, Mafune K, Kaminishi M, Aikou T, Arai K, Ohta K, Nashimoto A, Honda I, et al. Lymph node metastasis and preoperative diagnosis of depth of invasion in early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:34–38. doi: 10.1007/s101200100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boku T, Nakane Y, Okusa T, Hirozane N, Imabayashi N, Hioki K, Yamamoto M. Strategy for lymphadenectomy of gastric cancer. Surgery. 1989;105:585–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee E, Chae Y, Kim I, Choi J, Yeom B, Leong AS. Prognostic relevance of immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastasis in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2867–2873. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren G, Cai R, Zhang WJ, Ou JM, Jin YN, Li WH. Prediction of risk factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3096–3107. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwee RM, Kwee TC. Imaging in assessing lymph node status in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10120-008-0492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seevaratnam R, Cardoso R, McGregor C, Lourenco L, Mahar A, Sutradhar R, Law C, Paszat L, Coburn N. How useful is preoperative imaging for tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging of gastric cancer? A meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S3–18. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puli SR, Batapati Krishna Reddy J, Bechtold ML, Antillon MR, Ibdah JA. How good is endoscopic ultrasound for TNM staging of gastric cancers? A meta-analysis and systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4011–4019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cardoso R, Coburn N, Seevaratnam R, Sutradhar R, Lourenco LG, Mahar A, Law C, Yong E, Tinmouth J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the utility of EUS for preoperative staging for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S19–S26. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mocellin S, Marchet A, Nitti D. EUS for the staging of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1122–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JH, Song KS, Youn YH, Lee YC, Cheon JH, Song SY, Chung JB. Clinicopathologic factors influence accurate endosonographic assessment for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagahama T, Yao K, Maki S, Yasaka M, Takaki Y, Matsui T, Tanabe H, Iwashita A, Ota A. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging for determining the horizontal extent of early gastric cancer when there is an unclear margin by chromoendoscopy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1259–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiyotoki S, Nishikawa J, Satake M, Fukagawa Y, Shirai Y, Hamabe K, Saito M, Okamoto T, Sakaida I. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging for determining gastric tumor margin. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1636–1641. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kikuchi D, Iizuka T, Hoteya S, Yamada A, Furuhata T, Yamashita S, Domon K, Nakamura M, Matsui A, Mitani T, et al. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging for determining tumor invasion depth in early gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:217695. doi: 10.1155/2013/217695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li HY, Dai J, Xue HB, Zhao YJ, Chen XY, Gao YJ, Song Y, Ge ZZ, Li XB. Application of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging in diagnosing gastric lesions: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1124–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida T, Kawachi H, Sasajima K, Shiokawa A, Kudo SE. The clinical meaning of a nonstructural pattern in early gastric cancer on magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:48–54. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00373-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobara H, Mori H, Fujihara S, Kobayashi M, Nishiyama N, Nomura T, Kato K, Ishihara S, Morito T, Mizobuchi K, et al. Prediction of invasion depth for submucosal differentiated gastric cancer by magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:841–847. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida T, Inoue H, Usui S, Satodate H, Fukami N, Kudo SE. Narrow-band imaging system with magnifying endoscopy for superficial esophageal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanao H, Tanaka S, Oka S, Hirata M, Yoshida S, Chayama K. Narrow-band imaging magnification predicts the histology and invasion depth of colorectal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uedo N, Fujishiro M, Goda K, Hirasawa D, Kawahara Y, Lee JH, Miyahara R, Morita Y, Singh R, Takeuchi M, et al. Role of narrow band imaging for diagnosis of early-stage esophagogastric cancer: current consensus of experienced endoscopists in Asia-Pacific region. Dig Endosc. 2011;23 Suppl 1:58–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2011.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okada K, Fujisaki J, Kasuga A, Omae M, Hirasawa T, Ishiyama A, Inamori M, Chino A, Yamamoto Y, Tsuchida T, et al. Diagnosis of undifferentiated type early gastric cancers by magnification endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1262–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oda I, Oyama T, Abe S, Ohnita K, Kosaka T, Hirasawa K, Ishido K, Nakagawa M, Takahashi S. Preliminary results of multicenter questionnaire study on long-term outcomes of curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:214–219. doi: 10.1111/den.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwee RM, Kwee TC. Predicting lymph node status in early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2008;11:134–148. doi: 10.1007/s10120-008-0476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tong JH, Sun Z, Wang ZN, Zhao YH, Huang BJ, Li K, Xu Y, Xu HM. Early gastric cancer with signet-ring cell histologic type: risk factors of lymph node metastasis and indications of endoscopic surgery. Surgery. 2011;149:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim HM, Pak KH, Chung MJ, Cho JH, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Kim CB, Lee YC, Song SY, Lee SK. Early gastric cancer of signet ring cell carcinoma is more amenable to endoscopic treatment than is early gastric cancer of poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma in select tumor conditions. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3087–3093. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1674-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li H, Lu P, Lu Y, Liu C, Xu H, Wang S, Chen J. Predictive factors of lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated early gastric cancers and application of endoscopic mucosal resection. Surg Oncol. 2010;19:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park JM, Kim SW, Nam KW, Cho YK, Lee IS, Choi MG, Chung IS, Song KY, Park CH, Jung CK. Is it reasonable to treat early gastric cancer with signet ring cell histology by endoscopic resection? Analysis of factors related to lymph-node metastasis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1132–1135. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832a21d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kunisaki C, Takahashi M, Nagahori Y, Fukushima T, Makino H, Takagawa R, Kosaka T, Ono HA, Akiyama H, Moriwaki Y, et al. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in histologically poorly differentiated type early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:498–503. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanaoka N, Tanabe S, Mikami T, Okayasu I, Saigenji K. Mixed-histologic-type submucosal invasive gastric cancer as a risk factor for lymph node metastasis: feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2009;41:427–432. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ye BD, Kim SG, Lee JY, Kim JS, Yang HK, Kim WH, Jung HC, Lee KU, Song IS. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis and endoscopic treatment strategies for undifferentiated early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park YD, Chung YJ, Chung HY, Yu W, Bae HI, Jeon SW, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO. Factors related to lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic mucosal resection for treating poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Endoscopy. 2008;40:7–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, Lu P, Lu Y, Liu CG, Xu HM, Wang SB, Chen JQ. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in poorly differentiated early gastric cancer and their impact on the surgical strategy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4222–4226. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li C, Kim S, Lai JF, Oh SJ, Hyung WJ, Choi WH, Choi SH, Zhu ZG, Noh SH. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:764–769. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9707-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ha TK, An JY, Youn HK, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S. Indication for endoscopic mucosal resection in early signet ring cell gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:508–513. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9660-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hyung WJ, Cheong JH, Kim J, Chen J, Choi SH, Noh SH. Application of minimally invasive treatment for early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2004;85:181–185; discussion 186. doi: 10.1002/jso.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abe N, Watanabe T, Sugiyama M, Yanagida O, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Endoscopic treatment or surgery for undifferentiated early gastric cancer? Am J Surg. 2004;188:181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee JH, Choi MG, Min BH, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Kim S. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in patients with poorly differentiated early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1688–1692. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chung JW, Jung HY, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jang SJ, Park YS, Yook JH, Oh ST, Kim BS, et al. Extended indication of endoscopic resection for mucosal early gastric cancer: analysis of a single center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:884–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hirasawa T, Fujisaki J, Fukunaga T, Yamamoto Y, Yamaguchi T, Katori M, Yamamoto N. Lymph node metastasis from undifferentiated-type mucosal gastric cancer satisfying the expanded criteria for endoscopic resection based on routine histological examination. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:267–270. doi: 10.1007/s10120-010-0577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Haruta H, Hosoya Y, Sakuma K, Shibusawa H, Satoh K, Yamamoto H, Tanaka A, Niki T, Sugano K, Yasuda Y. Clinicopathological study of lymph-node metastasis in 1,389 patients with early gastric cancer: assessment of indications for endoscopic resection. J Dig Dis. 2008;9:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song SY, Park S, Kim S, Son HJ, Rhee JC. Characteristics of intramucosal gastric carcinoma with lymph node metastatic disease. Histopathology. 2004;44:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Choi J, Kim SG, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Endoscopic estimation of tumor size in early gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2329–2336. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kang KJ, Kim KM, Kim JJ, Rhee PL, Lee JH, Min BH, Rhee JC, Kushima R, Lauwers GY. Gastric extremely well-differentiated intestinal-type adenocarcinoma: a challenging lesion to achieve complete endoscopic resection. Endoscopy. 2012;44:949–952. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kang HY, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for undifferentiated early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:509–516. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0614-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim JH, Lee YC, Kim H, Song KH, Lee SK, Cheon JH, Kim H, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Kim CB, et al. Endoscopic resection for undifferentiated early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee HL, Choi CH, Cheung DY. Do we have enough evidence for expanding the indications of ESD for EGC? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2597–2601. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i21.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kamada K, Tomatsuri N, Yoshida N. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for undifferentiated early gastric cancer as the expanded indication lesion. Digestion. 2012;85:111–115. doi: 10.1159/000334681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okada K, Fujisaki J, Kasuga A, Omae M, Yoshimoto K, Hirasawa T, Ishiyama A, Yamamoto Y, Tsuchida T, Hoshino E, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography is valuable for identifying early gastric cancers meeting expanded-indication criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:841–848. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Akahoshi K, Chijiwa Y, Hamada S, Sasaki I, Nawata H, Kabemura T, Yasuda D, Okabe H. Pretreatment staging of endoscopically early gastric cancer with a 15 MHz ultrasound catheter probe. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:470–476. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hizawa K, Iwai K, Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Suekane H, Iida M. Is endoscopic ultrasonography indispensable in assessing the appropriateness of endoscopic resection for gastric cancer? Endoscopy. 2002;34:973–978. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim YY, Jeon SW, Kim J, Park JC, Cho KB, Park KS, Kim E, Chung YJ, Kwon JG, Jung JT, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer with undifferentiated histology: could we extend the criteria beyond? Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4656–4662. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Akashi K, Yanai H, Nishikawa J, Satake M, Fukagawa Y, Okamoto T, Sakaida I. Ulcerous change decreases the accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography diagnosis for the invasive depth of early gastric cancer. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2006;37:133–138. doi: 10.1007/s12029-007-9004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sako A, Kitayama J, Ishikawa M, Yamashita H, Nagawa H. Impact of immunohistochemically identified lymphatic invasion on nodal metastasis in early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jung da H, Park YM, Kim JH, Lee YC, Youn YH, Park H, Lee SI, Kim JW, Choi SH, Hyung WJ, et al. Clinical implication of endoscopic gross appearance in early gastric cancer: revisited. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3690–3695. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2947-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Song IC, Liang ZL, Lee JC, Huang SM, Kim HY, Oh YS, Yun HJ, Sul JY, Jo DY, Kim S, et al. Expression of stromal cell-derived factor-1α is an independent risk factor for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2011;2:1197–1202. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jeon SR, Cho JY, Bok GH, Lee TH, Kim HG, Cho WY, Jin SY, Kim YS. Does immunohistochemical staining have a clinical impact in early gastric cancer conducted endoscopic submucosal dissection? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4578–4584. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yonemura Y, Endou Y, Tabachi K, Kawamura T, Yun HY, Kameya T, Hayashi I, Bandou E, Sasaki T, Miura M. Evaluation of lymphatic invasion in primary gastric cancer by a new monoclonal antibody, D2-40. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abe S, Oda I, Suzuki H, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Odagaki T, Taniguchi H, Kushima R, Saito Y. Short- and long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for undifferentiated early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2013;45:703–707. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Park J, Choi KD, Kim MY, Lee JH, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY, Kim JH. Is endoscopic resection an acceptable treatment for undifferentiated EGC? Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:607–611. doi: 10.5754/hge11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Okada K, Fujisaki J, Yoshida T, Ishikawa H, Suganuma T, Kasuga A, Omae M, Kubota M, Ishiyama A, Hirasawa T, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2012;44:122–127. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yamamoto Y, Fujisaki J, Hirasawa T, Ishiyama A, Yoshimoto K, Ueki N, Chino A, Tsuchida T, Hoshino E, Hiki N, et al. Therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection of undifferentiated-type intramucosal gastric cancer without ulceration and preoperatively diagnosed as 20 millimetres or less in diameter. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee H, Yun WK, Min BH, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim KM, Rhee JC, Kim JJ. A feasibility study on the expanded indication for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1985–1993. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ahn JY, Jung HY, Choi KD, Choi JY, Kim MY, Lee JH, Choi KS, Kim do H, Song HJ, Lee GH, et al. Endoscopic and oncologic outcomes after endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: 1370 cases of absolute and extended indications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, Akiyama M, Ozawa E, Ohnita K, Hayashi T, Nakao K, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer by indication criteria. Digestion. 2009;80:173–181. doi: 10.1159/000215388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kumarasinghe MP, Lim TK, Ooi CJ, Luman W, Tan SY, Koh M. Tubule neck dysplasia: precursor lesion of signet ring cell carcinoma and the immunohistochemical profile. Pathology. 2006;38:468–471. doi: 10.1080/00313020600924542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sawada S, Fujisaki J, Yamamoto N, Kato Y, Ishiyama A, Ueki N, Hirasawa T, Yamamoto Y, Tsuchida T, Tatewaki M, et al. Expansion of indications for endoscopic treatment of undifferentiated mucosal gastric cancer: analysis of intramucosal spread in resected specimens. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1376–1380. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0883-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huh CW, Jung da H, Kim JH, Lee YC, Kim H, Kim H, Yoon SO, Youn YH, Park H, Lee SI, et al. Signet ring cell mixed histology may show more aggressive behavior than other histologies in early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:124–129. doi: 10.1002/jso.23261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Luinetti O, Fiocca R, Villani L, Alberizzi P, Ranzani GN, Solcia E. Genetic pattern, histological structure, and cellular phenotype in early and advanced gastric cancers: evidence for structure-related genetic subsets and for loss of glandular structure during progression of some tumors. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:702–709. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zheng HC, Li XH, Hara T, Masuda S, Yang XH, Guan YF, Takano Y. Mixed-type gastric carcinomas exhibit more aggressive features and indicate the histogenesis of carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:525–534. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maruyama K, Kaminishi M, Hayashi K, Isobe Y, Honda I, Katai H, Arai K, Kodera Y, Nashimoto A. Gastric cancer treated in 1991 in Japan: data analysis of nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:51–66. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0370-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N. A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:68–72. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225364.03133.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Mizuta Y, Shiozawa J, Kohno S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331–336. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.165381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goto O, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Ono S, Omata M. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer with special reference to validation for curability criteria. Endoscopy. 2009;41:118–122. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gotoda T, Iwasaki M, Kusano C, Seewald S, Oda I. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer treated by guideline and expanded National Cancer Centre criteria. Br J Surg. 2010;97:868–871. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, Tsujitani S, Seto Y, Furukawa H, Oda I, et al. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0163-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nakajima T, Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Yokoi C, Saito D. Metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection: how effective is annual endoscopic surveillance? Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nasu J, Doi T, Endo H, Nishina T, Hirasaki S, Hyodo I. Characteristics of metachronous multiple early gastric cancers after endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2005;37:990–993. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nicholls JC. Stump cancer following gastric surgery. World J Surg. 1979;3:731–736. doi: 10.1007/BF01654802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Takeda J, Toyonaga A, Koufuji K, Kodama I, Aoyagi K, Yano S, Ohta J, Shirozu K. Early gastric cancer in the remnant stomach. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1907–1911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Seo JH, Park JC, Kim YJ, Shin SK, Lee YC, Lee SK. Undifferentiated histology after endoscopic resection may predict synchronous and metachronous occurrence of early gastric cancer. Digestion. 2010;81:35–42. doi: 10.1159/000235921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kato M, Nishida T, Yamamoto K, Hayashi S, Kitamura S, Yabuta T, Yoshio T, Nakamura T, Komori M, Kawai N, et al. Scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: a multicentre retrospective cohort study by Osaka University ESD study group. Gut. 2013;62:1425–1432. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Takeuchi H, Kitagawa Y. New sentinel node mapping technologies for early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:522–532. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang Z, Dong ZY, Chen JQ, Liu JL. Diagnostic value of sentinel lymph node biopsy in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1541–1550. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cardoso R, Bocicariu A, Dixon M, Yohanathan L, Seevaratnam R, Helyer L, Law C, Coburn NG. What is the accuracy of sentinel lymph node biopsy for gastric cancer? A systematic review. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S48–S59. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lips DJ, Schutte HW, van der Linden RL, Dassen AE, Voogd AC, Bosscha K. Sentinel lymph node biopsy to direct treatment in gastric cancer. A systematic review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cahill RA, Asakuma M, Perretta S, Leroy J, Dallemagne B, Marescaux J, Coumaros D. Supplementation of endoscopic submucosal dissection with sentinel node biopsy performed by natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1152–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Asakuma M, Nomura E, Lee SW, Tanigawa N. Ancillary N.O.T.E.S. procedures for early stage gastric cancer. Surg Oncol. 2009;18:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang J, Yu JC, Kang WM, Ma ZQ. Treatment strategy for early gastric cancer. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nakajima K, Nishida T, Takahashi T, Souma Y, Hara J, Yamada T, Yoshio T, Tsutsui T, Yokoi T, Mori M, et al. Partial gastrectomy using natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) for gastric submucosal tumors: early experience in humans. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2650–2655. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ramos AC, Zundel N, Neto MG, Maalouf M. Human hybrid NOTES transvaginal sleeve gastrectomy: initial experience. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:660–663. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Madan AK, Tichansky DS, Khan KA. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic gastric bypass performed in a cadaver. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1192–1199. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cho WY, Kim YJ, Cho JY, Bok GH, Jin SY, Lee TH, Kim HG, Kim JO, Lee JS. Hybrid natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery: endoscopic full-thickness resection of early gastric cancer and laparoscopic regional lymph node dissection--14 human cases. Endoscopy. 2011;43:134–139. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]