Abstract

Data uncertainty is inherent in many real-world applications such as sensor monitoring systems, location-based services, and medical diagnostic systems. Moreover, many real-world applications are now capable of producing continuous, unbounded data streams. During the recent years, new methods have been developed to find frequent patterns in uncertain databases; nevertheless, very limited work has been done in discovering frequent patterns in uncertain data streams. The current solutions for frequent pattern mining in uncertain streams take a FP-tree-based approach; however, recent studies have shown that FP-tree-based algorithms do not perform well in the presence of data uncertainty. In this paper, we propose two hyper-structure-based false-positive-oriented algorithms to efficiently mine frequent itemsets from streams of uncertain data. The first algorithm, UHS-Stream, is designed to find all frequent itemsets up to the current moment. The second algorithm, TFUHS-Stream, is designed to find frequent itemsets in an uncertain data stream in a time-fading manner. Experimental results show that the proposed hyper-structure-based algorithms outperform the existing tree-based algorithms in terms of accuracy, runtime, and memory usage.

Keywords: Data mining, Data stream, Data uncertainty, Frequent patterns

1 Introduction

Frequent pattern mining (FPM) is a broadly studied area in data mining. It has many application domains such as association rule mining, sequential pattern mining, structured pattern mining, maximal pattern mining, and so on [2,3,5,12,19,25,30]. Today, many emerging real-world applications are capable of producing continuous, infinite streams of data. Compared to mining frequent patterns from a static database, mining data streams are more challenging. Due to the dynamic behavior of streaming data, infrequent items can become frequent later on and hence cannot be ignored. The storage structures need to be dynamically adjusted to reflect the evolution of itemset frequencies over time. Due to the infinite volume, data cannot be completely stored, and only a single pass over the data can be afforded.

Over the past decade, a number of stream mining algorithms have been proposed to mine frequent patterns from data streams. Manku and Motwani [21] proposed the Lossy Counting algorithm, which mines frequent patterns in data streams by assuming that patterns are measured from the start of the stream up to the current moment. Giannella et al. [10] proposed a tree-based algorithm called FP-streaming to mine frequent patterns with a tilted-time window model. Both these methods follow a false-positive oriented approach. Yu et al. [27] proposed a false-negative-oriented approach. Lately, there were many extensions and improvements proposed [18,22,23,26]. Two surveys on FPM in data streams can be found in [20] and [7].

The FPM algorithms mentioned above assume the availability of precise input data. However, data tend to be uncertain in many real-world applications. Uncertainty can be caused by various factors including data collection equipment errors, precision limitations, data sampling errors, and transmission errors. For example, data collected from sensors are usually inaccurate and noisy. The information obtained through RFID and GPS systems are imprecise. In the medical domain, a physician may diagnose a patient to have a certain disease with some probability. In some applications, data are intentionally made uncertain due to privacy or other concerns.

During the recent years, several algorithms have been proposed to address FPM in uncertain databases [1,4,8,9,13,28]. In an uncertain dataset, existence of an item in a transaction is associated with a likelihood measure or existential probability. The consideration of the existential probabilities makes FPM techniques perform differently on uncertain data than they perform on precise data. For example, tree-based algorithms following FP-growth [11] are well known to be highly efficient for mining frequent patterns in precise datasets. However, a recent study has shown that the hyper-structure algorithms based on H-mine [24] and the candidate generate-and-test algorithms based on Apriori [2] perform much better than the tree-based algorithms in the presence of uncertain data [1].

Above-mentioned works on frequent pattern mining in uncertain data focus on static datasets. However, many emerging applications produce massive data streams, and these data streams tend to be uncertain. Let us consider a traffic monitoring application. Table 1 shows some example records collected at accident sites. A traffic analyzing officer might be interest in finding the common causes of accidents; for instance, {speed > 60, rain} would be one such cause, {location = x} could be another one.

Table 1.

Sample records from a traffic monitoring data stream

| TID | Location | Speed | Weather | Traffic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | x (1.00) | 60 (0.85) | Rainy (0.87) | High (0.90) |

| 2 | y (0.90) | 40 (0.90) | Snow (0.95) | Low (0.87) |

| 3 | x (0.85) | 65 (0.65) | Rainy (0.77) | Low (0.65) |

| 4 | x (0.75) | 45 (0.85) | Rainy (0.97) | High (0.80) |

| 5 | y (0.95) | 70 (0.75) | Sunny (0.90) | Low (0.77) |

As illustrated in Table 1, each data item is associated with an existential probability. This is introduced by the sensor measurement errors, as well as the flaws caused by automatic information extraction of the photographs taken by the cameras. Because of the uncertainty inherent in data collection equipments, existing stream mining techniques cannot be directly applied to this type of applications.

Very limited work has been done to address FPM in uncertain data streams, and either they are built-on a tree-based approach [15–17] or they are limited to mine frequent patterns only from the most recent window [14,29]. In this paper, we present two false-positive-oriented, hyper-structure-based algorithms to mine frequent patterns from an uncertain data stream. The first algorithm, UHS-Stream (Uncertain Hyper-Structure Stream mining), is proposed to mine frequent patterns from the start of the stream up to the current moment. In some applications, recent transactions are of more interest than historical data in data streams; thus, the older transactions can be gradually discarded. To address this necessity, we propose the second algorithm, TFUHS-Stream (time-fading (TF) model for Uncertain Hyper-Structure Stream mining), to find frequent patterns in an uncertain data stream using a TF model. To summarize, we list our contributions as follows:

First, we propose the UHS-Stream algorithm to mine all the frequent patterns seen up to the current moment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first false-positive-oriented solution to find the complete set of frequent patterns from an uncertain data stream.

We also propose the TFUHS-Stream algorithm, a false-positive-oriented TF model to mine frequent patterns from an uncertain data stream. For applications which value recent transactions more than historical data, this method is especially effective.

Through extensive experiments, we demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed algorithms in terms of accuracy, runtime, and memory usage.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides some background information on FPM in uncertain data. In Sect. 3, we define the FPM problem for uncertain data streams and present the UHS-Stream and the TFUHS-Stream algorithms. Section 4 reports the results of experimental evaluation and performance study. Section 5 discusses the related work, and Sect. 6 concludes the paper.

2 Preliminaries

2.1 Frequent pattern mining in uncertain data

The difference between precise and uncertain data is that each item of an uncertain transaction contains an existential probability for that item. The existential probability P(x, ti) of an item x in a transaction ti indicates the likelihood of x being present in ti. According to the “possible worlds” interpretation of uncertain data [8], there are two possible worlds for an item x and a transaction ti. In one world (W1), item x is present in transaction ti ; in the other (W2), item x is not present in ti. Although it is uncertain which of these two worlds be the true world, the probability of W1 being the true world is P(x, ti) and that of W2 is 1 − P(x, ti). This idea can be extended to cover the generic case in which a transaction ti contains more than one item, and the dataset contains more than one transaction.

Let I = {x1, x2, …, xn} be a set of items. An itemset X is a subset of items, that is, X ⊆ I. Let an uncertain dataset D consist of d transactions {t1, t2, …, td}. Each transaction ti contains a subset of items drawn from I. Each item x in ti is associated with an existential probability P(x, ti). We assume that the items’ existential probabilities in transactions are independent. Then, the probability of an itemset X occurring in a given transaction ti is defined to be the product of the corresponding probabilities [8,9,13]. This is denoted by P(X, ti). Thus, we have the following relationship:

| (1) |

Given a world Wi, let us define P(Wi) as the probability of world Wi. We use t(i, j) to denote the transaction j in the world Wi. Then, P(Wi) is defined as follows:

| (2) |

Since the transactions are probabilistic in nature, it is impossible to count the frequency of the itemsets deterministically. Therefore, we count the frequent itemsets only in expected value. Let s(X, Wi) be the support count of X in world Wi. Then, the expected support of an itemset X in dataset D, which is denoted by E[s(X)], can be computed by summing the support of X in possible world Wi over all possible worlds:

| (3) |

where W is the set of possible worlds derived from an uncertain dataset D.

It is shown in [8] that the above equation can be simplified to become the following:

| (4) |

With this setting, the problem of frequent itemset mining can be defined in the context of uncertain databases as follows.

Definition 1

Given a dataset D and a minimum support threshold σ ∈ (0, 1), an itemset X is said to be frequent in D, if its expected support is not less than σ |D| (i.e. E[s(X)] ≥ σ |D|).

2.2 Basics of hyper-structure mining

As mentioned earlier, FPM techniques behave differently on uncertain data than they perform on precise data. Consideration of the existential probabilities causes the FP-growth [11] algorithm to lose its compression power and perform unsatisfactorily in the presence of uncertain data. Both hyper-structure and Apriori-based algorithms have performed much better than the tree-based algorithms in the presence of static uncertain data [1]. However, Apriori-based algorithms are not appropriate for data streams as they perform multiple scans over the data and require storing candidate itemsets. On the other hand, H-mine [24] can find frequent patterns with only two scans over the dataset and does not need to store candidate itemsets. Aggarwal et al. [1] have shown that H-mine can be efficiently extended for FPM in uncertain databases.

Same as FP-growth [11], H-mine [24] is also based on pattern growth paradigm; however, H-mine uses a hyper-linked array structure called the H-struct instead of the FP-tree. Initially, it scans the input database once to find the frequent items. The infrequent items are removed and the frequent items left in each transaction are sorted according to a certain global ordering scheme. The transformed database is stored in an array structure, where each row corresponds to one transaction. Each frequent item in a transaction is stored in an entry with two fields: an item-id and a hyper-link, which points to the next transaction containing that item. A header table is constructed with each frequent item entry having three fields: an item-id, a support count, and a hyper-link, which records the starting point of the projected transactions. H-mine can find the frequent itemsets by scanning the projected transactions linked together by the hyper-links.

As the hyper-linked array structure in H-mine is not in a compressed form, it is relatively easy to extend the H-struct to mine uncertain data [1]. For each item entry, a new field is added to record the existential probability [P(x, ti)] of the item x in transaction ti. The header table now records the expected support count for each frequent item. During the mining process, there always exists a prefix itemset (denoted by Q, which is initially empty). The locally frequent items with respect to prefix Q can be used to extend Q to longer prefix itemsets. P(Q, ti) is the probability of prefix Q with respect to the projected transaction ti. By scanning the sub-transaction before the projected transaction of prefix Q, we can find the probability of each item in Q; thus, P(Q, ti) can be computed according to Eq. (1). Then, it is straightforward to compute the expected support of a new itemset Q ∪ {x}(E[s(Q ∪ {x})]), according to Eq. (4).

Figure 1 shows an example of an extended UH-struct created for the transactions given in Table 2. Assume that the minimum support count is 0.75 (σ = 0.75/3 = 0.25). We start with item {a} and follow the hyper-links to get the {a} projected database. From the {a} projected database, we get the {a, c} projected database, and then the {a, c, d} projected database and so on. Initially, Q is empty, then, it is set to {a}, and then, it will be extended to {a, c}, then {a, c, d} and so on until it becomes infrequent. This will be repeated for all the items in the header table.

Fig. 1.

UH-struct created from the transactions given in Table 2

Table 2.

Example of an uncertain transaction database

| TID | Transaction |

|---|---|

| t1 | (a:0.9), (d:0.7), (f:0.1) |

| t2 | (a:0.8), (c:0.7), (d:0.6), (e:0.5) |

| t3 | (b:0.8), (c:0.8) |

3 Frequent pattern mining in uncertain data streams

3.1 Finding all frequent patterns in uncertain data streams

An uncertain stream S is a continuous sequence of transactions, {t1, t2, …, tn, …}. A transaction ti contains a number of items, and each item x in ti is associated with an existential probability P(x, ti). Let N be the number of transactions seen so far in the data stream. Given a minimum support parameter σ ∈ (0, 1), our goal is to find the complete set of patterns whose expected supports are higher than σN. Hence, we will define the problem of frequent pattern mining in the context of uncertain data streams as follows and present the UHS-Stream algorithm to address this problem.

Definition 2

Given an uncertain data stream S of length N and a minimum support threshold σ ∈ (0, 1), an itemset X is said to be frequent in S, if its expected support is not less than σN (i.e. E[s(X)] ≥ σN).

In streaming data, currently infrequent items can become frequent later on. Thus, to ensure that we capture all frequent itemsets, it is necessary to store not only the information related to frequent items, but also that related to infrequent items. Nevertheless, due to the infinite volume of data, one cannot maintain exact frequency counts for all itemsets. Therefore, we have to maintain approximate frequency counts within an acceptable error margin. There are two possible ways for approximating itemset frequencies, false-positive-oriented and false-negative-oriented. The false-positive approach outputs all truly frequent itemsets, however, may end up outputting some itemsets which have support less than the minimum support. The false-negative approach does not output any itemset whose support is less than the minimum support threshold; however, this approach might miss some of the truly frequent itemsets.

Manku and Motwani [21] proposed a false-positive-oriented approach for frequent pattern mining in precise data streams. We hereby extend this approach for uncertain data streams in conjunction with hyper-structure mining to find frequent patterns from uncertain data streams.

3.1.1 UHS-stream algorithm

Let E[strue(X)] denote the true expected support of the itemset X, and E[sest(X)] denote the estimated expected support of the itemset X. We will categorize the itemsets using a user-specified error margin ε ∈ (0, 1) [ε ≪ σ] as follows.

Definition 3

An itemset X is defined frequent if E[strue(X)] ≥ σN; X is defined sub-frequent if σN > E[strue(X)] ≥ εN; otherwise X is defined infrequent.

The UHS-Stream algorithm processes stream data in batches. First, we apply the UH-mine algorithm to find potentially frequent itemsets in the current batch. Then, these itemsets are maintained in a global tree structure called the IS-tree. Although we are only interested in the frequent itemsets, sub-frequent itemsets have to be maintained as well, since they may become frequent later on. In the IS-tree structure, each path represents either a frequent or a sub-frequent itemset. Common items in itemsets share the tree path in a similar fashion as in the FP-tree [11]. Each node in the IS-tree structure contains (i) the item, (ii) E[sest(X)]—the estimated expected support of the itemset forms by traversing from root to that node—, and (iii) Δ—the maximum possible error of E[sest(X)]. At each iteration of the algorithm, itemsets stored in the IS-tree are updated according to the information mined from the current batch. When the user queries for the frequent itemsets, the UHS-Stream algorithm traverses the IS-tree and delivers all itemsets X which have E[sest(X)] ≥ (σ − ε)N. As we will show in Sect. 3.1.2, it will output all frequent itemsets; there are no false-negatives. However, it might output some near-frequent itemsets with E[strue(X)] between σN and (σ − ε)N. It is guaranteed that none of the itemsets which have E[strue(X)] < (σ − ε)N are output.

Assume the incoming transaction stream is divided into batches of w transactions. Let Ni denote the length of the data stream at the end of ith batch and E[scrr(X)] denote the itemset X’s expected support calculated from the current batch. The first batch is used as the initialization step; therefore, it is processed differently from the rest of the batches. In the first scan, we compute the expected support of each item occurring in the first batch. Then, we scan the first batch for the second time to create the UH-struct. All items with expected support less than εw are removed from the transactions, and the transactions are sorted according to the alphabetical order1.The header table and the hyper-links are created as described in the previous section. Using this UH-struct, we find all the itemsets having E[scrr(X)] ≥ εw, and insert them into the IS-tree. Initially, E[sest(X)] is set to E[scrr(X)], and Δ is set to zero for all itemsets. After storing the potentially frequent itemsets in the IS-tree, the UH-struct is deleted. All the subsequent batches are mined according to the UHS-Stream algorithm given in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

UHS-stream Algorithm

At each iteration of the algorithm, the IS-tree structure is updated according to the transactions in the current batch. Here, the UH-struct is created without pruning any items; the reason is although an item appears to have a lower support in the current batch, it can be frequent when the previous batches are considered. If an itemset already exists in the IS-tree, its estimated support is incremented by its support in the current batch. If the incremented support plus the maximum possible error (Δ) does not satisfy the current threshold (εNi), that itemset and all its supersets are removed from the IS-tree. If an itemset cannot be found in the IS-tree, it will be inserted to the tree if its support is greater than εw. Although an itemset currently does not exist in the IS-tree, it is possible that this itemset occurred in the previous batches; but removed from IS-tree due to insufficient support count. To take this into account, Δ is set to εNi−1, which is the maximum possible support that a previously pruned itemset can have at this moment. Following the Apriori principle, if an itemset found to be infrequent in the current batch, none of its supersets will be considered in the current batch.

Delayed pruning mode

The purpose of the last step is to prune the infrequent itemsets that did not appear in the current batch. This pruning process involves going through all nodes in the IS-tree; therefore, it can be quite costly to perform this for each and every batch. One solution is to delay the pruning until the user queries for frequent itemsets. This will not affect the accuracy of the output since the pruning step is done before outputting the results; however, delayed pruning will increase the size of IS-tree, since infrequent itemsets remain in the IS-tree for a longer duration. In our experiments, we evaluated the performance of both pruning modes.

Consider the example uncertain transaction stream given in Table 3. Assume w = 3, σ = 0.5, and ε = 0.05. Here, we have chosen a smaller batch size and a higher support threshold for simplicity of illustration. Figure 3 depicts the initial IS-tree structure created after processing the first batch of data. It contains all itemsets whose expected support is not less than εw = 0.15. For example, node [a, 1.7, 0] represents the itemset {a} with E[S({a})] = 1.7. Similarly, path {[b, 0.8, 0], [c, 0.64, 0]} represents the itemset {b, c} with E[S({b, c})] = 0.64. Note that the item (f : 0.1) in t1 does not satisfy the εw threshold; therefore, neither f nor its supersets are added to the IS-tree at this point. Initially, Δ is set to zero for all itemsets. Figure 4 depicts the updated IS-tree structure after processing the second batch. In this batch, the item f reappears in t5 with probability 0.5; hence, it is a locally frequent item in the batch 2. Therefore, f and all its supersets which satisfy the εw threshold are added to the IS-tree with Δ set to εN1 = 0.15. Note that the updated IS-tree shown in Fig. 4 does not contain any itemsets whose expected support is less than εN2 = 0.30. Some of the itemsets present in Fig. 3 were pruned, and some new itemsets were added.

Table 3.

Example of uncertain transaction stream

| Batch # | TID | Transaction |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | t1 | (a:0.9), (d:0.7), (f:0.1) |

| t2 | (a:0.8), (c:0.7), (d:0.6), (e:0.5) | |

| t3 | (b:0.8), (c:0.8) | |

| 2 | t4 | (b:0.7), (c:0.8) |

| t5 | (a:0.8), (d:0.9), (f:0.5) | |

| t6 | (b:0.8), (d:0.6) |

Fig. 3.

IS-tree structure created after processing first batch

Fig. 4.

Updated IS-tree structure after processing the second batch

3.1.2 Correctness proof

Given a minimum support parameter σ, error margin ε, and stream length Ni, we will prove that the answers produced by UHS-Stream has the following guarantees,

All itemsets having E[strue(X)] ≥ σNi are output.

No itemset having E[strue(X)] < (σ − ε)Ni is output.

Consider an itemset X occurring in batch i. If it is not found in the IS-tree, there are two possibilities, either this is X’s first occurrence or it was possibly deleted in the first i − 1 batches. When the last such deletion took place, E[strue(X)] is at most εNi−1. Thus, for any itemset X found in IS-tree at the end of iteration i, the following conditions hold.

Δ ≤ εNi−1 ≤ εNi => Δ ≤ εNi

E[sest(X)] ≤ E[strue(X)] ≤ E[sest(X)] + Δ

Therefore, we can rewrite the mining condition E[strue(X)] ≥ σNi as E[sest(X)] + εNi ≥ σNi. Hence, if we output all itemsets having E[sest(X)] ≥ (σ − ε)Ni, we will output the complete set of frequent itemsets seen so far in the data stream. Note that we will not output any itemset having E[sest(X)] < (σ − ε)Ni. For any itemset, E[sest(X)] ≤ E[strue(X)]; therefore, no itemset having E[strue(X)] < (σ − ε)Ni is output.

3.2 Mining uncertain data streams using time-fading model

Typically, in a streaming environment, recent transactions are of more interest than the historical data; thus, the older transactions can be gradually discarded, favoring the new transactions. In this model, the entire data stream is taken into account to compute the frequency of each data item, but more recent data items contribute more to the frequency than the older ones. This is achieved by introducing a fading factor λ ∈ (0, 1). A data item that comes k time steps earlier is weighted λk, and this weight is exponentially decreasing. In general, the closer to 1 the fading factor λ is, the more important the history is taken into account.

For example, consider a transaction stream produced by a grocery store. Table 4 shows the frequency counts for the item ‘Pumpkin Decor’ for each batch and the query results obtained using TF model and non-time-fading (NTF) model at the end of each batch. FI stands for frequent item; NFI stands for non-frequent item.

Table 4.

Query results for the item “Pumpkin Décor”

| Batch | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 150 | 120 | 280 | 400 | 40 | 15 | 10 |

| NTF model | FI | FI | FI | FI | FI | FI | FI |

| TF model | FI | FI | FI | FI | FI | NFI | NFI |

Assume that we process transactions in batches of 1000 and looking for frequent items with minimum support 10 % (σ = 0.1). If we consider the NTF model, support count of the item ‘Pumpkin Decor’ at the end of the 6th batch is,

This is greater than σ; therefore, it is identified as a currently frequent item. However, according to the last two batches, ‘Pumpkin Décor’ is not a frequent item. If we use a TF model with fading factor 0.5 (λ = 0.5), support count of this item at the end of the 6th batch is,

This is less than σ; therefore, it is not identified as a currently frequent item. Same scenario occurs at the end of the 7th batch.

From the above example, it can be observed that the TF model can quickly adjust to the current trend of the streaming data by gradually discarding obsolete information. Also, the TF model is more accurate compared to the sliding window model. In TF model, frequency takes into account the old data items in the history while sliding window model only considers a limited time window and entirely ignores the transactions that fall out of the window. Hence, for the data streams with seasonal trends, it is more appropriate to use the TF model.

Next, we present the TFUHS-Stream algorithm, which finds frequent patterns in an uncertain data stream using the TF model. Using a fading factor λ, TFUHS-Stream prunes obsolete itemsets and limits the size of the IS-tree.

3.2.1 Fading factor definitions

As earlier, we process the data stream in batches of size w. Assume that the current batch number is i. Given a fading factor λ ∈ (0, 1), the decaying expected support of an itemset X in batch i is defined as follows:

| (5) |

where, Ei[scrr(X)] is the expected support of X calculated from the ith batch. This equation can be expanded to

| (6) |

We will define the accumulated fading factor Di as follows:

| (7) |

Thus, the decaying length of the data stream can be defined as follows:

| (8) |

Estimating a value for the fading factor

Value of λ determines how long we will carry out the effect of the previous transactions to the future decisions. Therefore, choosing a sensible value for λ is important. The value of λ can be decided using the half-life principle as follows.

Half-life, which is denoted by t1/2, is the period of time it takes for a substance undergoing decay to decrease by half. An exponential decay process can be described by the following formula:

| (9) |

where, C0 is the initial quantity of the substance that will decay, C(t) is the quantity that still remains after a time t, and α is a positive number called the decay constant of the decaying quantity.

We define the fading factor λ = e−α, thus, λi = e−αi. Using Eq. (9), we can derive that ; then, the value of the fading factor can be calculated using . For example, if t1/2 = 5 batches, then .

3.2.2 TFUHS-stream algorithm

At any time point t, let Et[strue(X)] denote the true decayed expected support of the itemset X, and Et[sest(X)] denote the estimated decayed expected support of the itemset X.

Definition 4

Given an uncertain data stream S with decayed length wDt, a minimum support threshold σ ∈ (0, 1), and fading factor λ ∈ (0, 1), an itemset X is said to be frequent in S, if its decayed expected support is not less than σwDt (i.e. Et[Strue(X)] ≥ σwDt).

The TFUHS-Stream algorithm also mines frequent itemsets using the UH-struct and maintain them in the IS-tree structure following a false-positive-oriented approach. The initialization step of the TFUHS-Stream algorithm is similar to that of the UHS-Stream algorithm. All the subsequent batches are mined according to the TFUHS-Stream algorithm given in Fig. 5. The main difference from the UHS-Stream algorithm is that at each iteration, the recorded estimated frequency count and the maximum possible error are decayed by a fading factor λ as shown in step 2. At any time point t, if the user queries for the frequent itemsets, the TFUHS-Stream algorithm traverses the IS-tree and delivers all itemsets X which have Et[sest(X)] ≥ (σ − ε)wDt.

Fig. 5.

TFUHS-stream Algorithm

Similar to the UHS-Stream, we can delay the final decaying and pruning step. For each itemset X in the IS-tree, we maintain the batch number where X is last updated (say l). Assume that we currently process the ith batch, then the decaying functions will be modified as follows:

Ei[sest(X)] = El[sest(X)] * λi−l + Ei[scrr(X)]

Δi = Δl * λi−l

If the user queries for frequent itemsets at the end of kth batch, traverse the IS-tree and apply the following decaying functions,

Ek[sest(X)] = El[sest(X)] * λk−l

Δk = Δl * λk−l

If the updated values satisfy Ek[sest(X)] (σ − ε) wDk, output itemset X.

At any time point t, answers produced by the TFUHS-Stream have the following guarantees. All itemsets having Et[strue(X)] ≥ σwDt are output. No itemset having Et[strue(X)] < (σ − ε) wDt is output. The correctness proof of the TFUHS-Stream algorithm is similar to UHS-Stream algorithm, except all the expected support counts, the max error values and the stream lengths should be replaced with their decayed values.

4 Experimental results

This section presents the performance evaluations for the proposed UHS-Stream and the TFUHS-Stream algorithms, in terms of accuracy, memory consumption, and runtime. All the algorithms are implemented in C++, and the experiments were performed in a notebook running Windows Vista with an IntelCore 2 Duo 2.0 GHz processor, and 3 GB main memory.

The performance of the UHS-Stream is compared with two FP-growth-based uncertain stream mining algorithms. As there were no existing false-positive-oriented, FP-growth-based algorithms, we implemented one and named it UFP-Stream. The UFP-Stream algorithm uses FP-tree structure to mine frequent patterns from uncertain data streams. The second one is the LUF-Streaming algorithm proposed in Leung et al. [17]. This is a false-negative-oriented approach, and it also uses FP-tree structure to mine frequent patterns from uncertain data streams. The performance of the TFUHS-Stream algorithm is compared with DUF-Streaming algorithm [15], which is a FP-growth-based, false-negative-oriented, TF model to mine frequent patterns from uncertain data streams. This is also similar to the TUF-Streaming algorithm proposed by the same authors [16]. We have implemented the LUF-Streaming [17] and the DUF-Streaming [15] algorithms following the guidelines given in respective papers.

4.1 Datasets

We performed our experiments using both synthetic and real-world datasets. Similar to previous work [8,10,13,14,21,29], we used the IBM synthetic market-basket data generator [2] to generate two synthetic datasets, T10I4D3000K and T15I10D3000K. Each has 3M transactions generated using 1K distinct items. In T10I4D3000K, average transaction length is 10 and maximum pattern length is 4. In T15I10D3000K, average transaction length is 15 and maximum pattern length is 10. All the other parameters are set to default values for both datasets.

In order to obtain uncertain data streams, we introduced the uncertainty to each item in the above datasets. We allocated a relatively high probability to each item in the datasets in order to allow the generation of longer itemsets and provide a more challenging testing environment. Existential probabilities were independently and randomly generated in the range of [0.60, 0.99], for each item in each transaction. Note that in the IBM simulator, the underlying statistical model used to generate the transactions does not change as the stream progresses; however, in reality, seasonal variations may cause the underlying data generation model to change over time. To inject this dynamic behavior into the data stream, we periodically applied some random permutations to the item names [10].

Our real-world dataset is a retail market-basket dataset supplied by an anonymous Belgian retail supermarket store [6]. Original dataset had around 84,000 transactions and 16,470 unique items. The average transaction length is 13 items. We extended this dataset to 1 M transactions by periodically repeating the transactions and applying some random permutations to the item names. We also added existential probabilities to each item in each transaction to make it an uncertain dataset.

Each data stream was broken into batches of size 100 K transactions. The minimum support threshold σ was varied from 0.2 to 5 %, and error margin ε was set to 0.1σ. We compare the performance of the above-mentioned algorithms in terms of runtime, memory consumption, and accuracy. All the reported values have been averaged over multiple runs on the same dataset.

4.2 Pruning mode comparison

First, we compared the performance of the two pruning modes: immediate pruning (I) and delayed pruning (D). The immediate pruning algorithm is named UHS-Stream(I), and the delayed pruning algorithm is named UHS-Stream(D). Runtime includes CPU and I/O costs for both phases (UH-struct mining and IS-tree maintenance). Figure 6 presents the runtime comparison of pruning modes on the T10I4D3000K and the T15I10D3000K datasets. The horizontal axis represents the batch number, and the vertical axis represents the runtime in seconds. The minimum support threshold (σ) is set to 0.01.

Fig. 6.

Runtime comparison on pruning modes

It is visible that there is only a slight difference in the runtime graphs for the respective immediate pruning and the delayed pruning methods. The reason behind is that the time consumptions of the algorithms are dominated by the mining phase, which is identical for both methods; thus, the difference caused by the pruning phase has become insignificant. For both pruning modes, runtime on the T15I10D3000K is higher than that on the T10I4D3000K. This is acceptable since the T15I10D3000K is a relatively dense dataset.

Memory usage measurements include space required for UH-struct, IS-tree, and any other intermediate headers. Figure 7 presents the memory usage comparison of pruning modes on the T10I4D3000K and the T15I10D3000K datasets. The horizontal axis represents the batch number, and the vertical axis represents the maximum memory consumption at each iteration. σ is set to 0.01. Note that there is no noticeable difference in the memory consumption of respective immediate pruning and delayed pruning methods. The reason behind this observation is that the pruning method only affects the size of the IS-tree, not the UH-struct. The memory consumptions of the algorithms are dominated by the UH-struct created to store the transactions; thus, the difference caused by the pruning phase has become insignificant.

Fig. 7.

Memory usage comparison on pruning modes

4.3 Runtime and memory comparison

In this section, we compare the runtime and memory consumption of the proposed UHS-Stream algorithm with the LUF-Streaming [17] and the UFP-Stream algorithms. The LUF-Streaming algorithm [17] uses delayed pruning; henceforth, we will also use the delayed pruning mode in our experiments.

Figures 8, 9, and 10 present the average runtime per iteration under different minimum support thresholds on the T10I4D3000K, the T15I10D3000K, and the retail datasets, respectively. It is visible that the UHS-Stream algorithm outperforms the other two algorithms on all three datasets. As expected, runtime decreases with increasing minimum support. It can be noted that the UHS-Stream algorithm performs well at all support thresholds.

Fig. 8.

Minimum support versus runtime on T10I4D3000K dataset

Fig. 9.

Minimum support versus runtime on T15I10D3000K dataset

Fig. 10.

Minimum support versus runtime on real-world retaildataset

Figures 11, 12, and 13 present the maximum memory usage under different minimum support thresholds on the T10I4D3000K, the T15I10D3000K, and the retail datasets, respectively. It is visible that the UHS-Stream algorithm clearly outperforms the other two algorithms at all support thresholds. Even with rounded off item probabilities,2 memory consumption of UFP-Stream and LUF-Streaming [17] algorithms is twice as high as that of UHS-Stream algorithm. Because of data uncertainty, FP-tree created by the UFP-Stream/LUF-Streaming loses its concise behavior and becomes almost equivalent to the UH-struct. After creating the UH-struct, UHS-Stream does not have to create any physical intermediate projections. It mines frequent itemsets only by creating the virtual projections using the hyper-links. However, UFP-Stream and LUF-Streaming algorithms have to create intermediate FP-trees, which cost them more memory and runtime.

Fig. 11.

Minimum support versus memory usage on T10I4D3000K dataset

Fig. 12.

Minimum support versus memory usage on T15I10D3000K dataset

Fig. 13.

Minimum support versus memory usage on real-world retail dataset

It is visible that for all algorithms, there is no significant decrease in the memory consumption with increasing minimum support. The reason is memory consumptions of the algorithms are dominated by the UH-struct or the FP-tree created to store the transactions. When creating the UH-struct or the FP-tree, we do not prune any items. Thus, size of these structures is not affected by the minimum support threshold.

4.4 Accuracy comparison

Precision and Recall are widely used measures for evaluating the accuracy of data mining algorithms. Let TP denote the number of true-positives and FP denote the number of false-positives. Similarly, TN denotes the number of true-negatives and FN denotes the number of false-negatives. Then, the precision and the recall measures are defined as follows:

To facilitate an unbiased comparison of the proposed false-positive-oriented approach, UHS-Stream, with existing false-negative-oriented approach, LUF-Streaming [17], it is necessary to combine the above two measures. A measure that combines the precision and the recall is the F-Score, which is defined as:

Accuracy of the UFP-Stream is almost similar to the UHS-Stream as both algorithms follow a false-positive approach. However, as shown in previous section, UFP-Stream has the worst performance in terms of memory consumption and runtime. Therefore, here, we only present the comparison of the UHS-Stream and the LUF-Streaming algorithms. Figures 14, 15, and 16 present the comparison of the F-Scores obtained at different support thresholds for the T10I4D3000K, the T15I10D3000K, and the real-world retail datasets, respectively.

Fig. 14.

Accuracy comparison on T10I4D3000K dataset

Fig. 15.

Accuracy comparison on T15I10D3000K dataset

Fig. 16.

Accuracy comparison on real-world retail dataset

It is visible that the UHS-Stream algorithm has better or equivalent performance compared to the LUF-Streaming [17] algorithm most of the time. When the minimum support threshold is set to higher values, performance of the false-positive-oriented approaches may slightly drop since there are very few truly frequent patterns. However, higher support thresholds are not much interesting case, since the data will no longer contain long frequent patterns. Also, it is worth mentioning that the false-positives produced by the UHS-Stream are bounded by the (σ − ε) threshold; whereas, there is no bound on the number of truly frequent itemsets that the LUF-Streaming algorithm might miss. Also, as shown in Sect. 4.3, the UHS-Stream achieves this accuracy using less memory and runtime compared to the LUF-Streaming. Therefore, it is evident that the UHS-Stream outperforms the LUF-Streaming in terms of memory, runtime, and the accuracy of the output.

4.5 Experiments on time-fading models

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the TFUHS-Stream algorithm. Unless stated differently, half-life parameter is set to 1 batch (resulting in a fading factor of 0.5). First, we compared the TFUHS-Stream and the UHS-Stream algorithms in terms of runtime and size of IS-tree.

Figure 17 presents a runtime comparison on the T15I10D3000K dataset. The horizontal axis represents the batch number, and the vertical axis represents the runtime in seconds. The minimum support threshold (σ) is set to 0.01. Similar to the previous experiments, the runtime graphs for the two pruning modes almost overlap; delayed pruning has slightly better runtime compared to immediate pruning. As expected, periodical permutations caused some fluctuations in the runtime graphs. It is visible that the runtime of the TFUHS-Stream algorithms is more subjected to periodical fluctuations. However, in most batches, the TFUHS-Stream algorithms are more efficient in runtime compared to the UHS-Stream algorithms.

Fig. 17.

Runtime comparison on T15I10D3000K dataset

Figure 18 shows the number of nodes remaining in the IS-tree structure at the end of the each iteration on the T15I10D3000K dataset. The minimum support threshold (σ) is set to 0.01. The periodical peaks in the graphs are caused by the item permutations. Compared to the UHS-Stream algorithms, the size of the IS-tree in the TFUHS-Stream algorithms quickly stabilized. This is due to the fact that the TFUHS-Stream gradually discards obsolete itemsets by exponentially decaying the older transactions. As expected, the size of the IS-tree in delayed pruning methods is slightly higher than their immediate pruning counterparts.

Fig. 18.

Comparison of number of nodes in IS-tree structure

Next, we compared the performance of the TFUHS-Stream with the existing DUF-Streaming algorithm [15] in delayed pruning mode. Figures 19 and 20 present the average runtime per iteration under different minimum support thresholds on the T10I4D3000K and the real-world retail datasets, respectively. Figures 21 and 22 present the maximum memory usage at different minimum support thresholds on the T10I4D3000K and the real-world retail datasets, respectively.

Fig. 19.

Minimum support versus runtime on T10I4D3000K dataset

Fig. 20.

Minimum support versus runtime on real-world retail dataset

Fig. 21.

Minimum support versus memory usage on T10I4D3000K dataset

Fig. 22.

Minimum support versus memory usage on real-world retail dataset

It is visible that the TFUHS-Stream outperforms the existing DUF-Streaming [15] algorithm in terms of runtime and memory usage at all support thresholds. Similar to the LUF-Streaming [17], the DUF-Streaming [15] also creates intermediate FP-trees, which cost it more memory and runtime, whereas the TFUHS-Stream only use virtual projections, thus making it more efficient. Also, it is worth recalling that the DUF-Streaming algorithm is false-negative-oriented, and there is no bound on the number of true frequent itemsets it might miss, whereas our TFUHS-Stream algorithm is false-positive-oriented, and the false-positives are bounded by the (σ − ε) threshold.

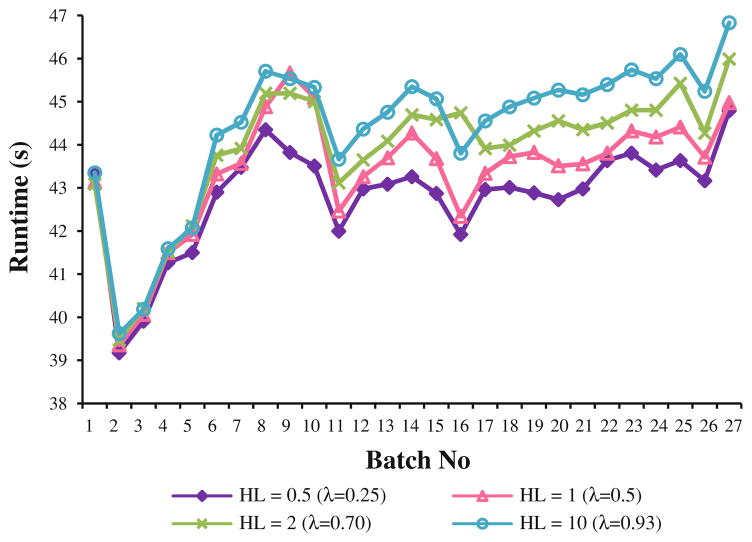

To evaluate the effect of the fading factor, we tested the performance of the TFUHS-Stream algorithm for different values of the half-life parameter. Figure 23 presents a runtime comparison, and Fig. 24 presents the number of nodes in IS-tree for half-life values 0.5, 1, 2, and 10; respective fading factors are given in brackets. As expected, the higher the fading factor, the higher the runtime, and the higher the size of IS-tree. When λ is close to 1, more weight is given to older transactions; thus, the behavior of the TFUHS-Stream becomes similar to the behavior of the UHS-Stream. When λ is close to zero, TFUHS-Stream rapidly discards the older transactions; thus, its behavior becomes similar to the sliding window approach.

Fig. 23.

Fading factor (λ) versus runtime

Fig. 24.

Fading factor (λ) versus number of nodes in IS-tree structure

5 Related work

Limited research has been carried out to address frequent pattern mining in uncertain data streams. Zhang and Peng [29] proposed a sliding window-based method to mine top-k frequent itemsets from uncertain data streams. Leung and Hao [14] proposed a FP-growth-based sliding window approach to mine frequent patterns from uncertain data streams. Both these approaches consider only the most recent window of data and entirely discard the historical transactions, whereas our UHS-Stream algorithm can mine all frequent itemsets from the entire data stream. Another limitation of UF-Streaming algorithm proposed in [14] is it rounds off the existential probability values to achieve space reduction; this will cause information loss and might produce inaccurate results. Very recently Leung et al. proposed a landmark model called LUF-Streaming [17] and a TF model called DUF-Streaming [15] or TUF-Streaming [16] to find frequent itemsets in uncertain data streams. These algorithms are based on their work in [14] and have the same limitation of rounding off item probabilities. Both LUF-Streaming and DUF-Streaming (or TUF-Streaming) algorithms are false-negative-oriented, and there is no theoretical bound on the quality of the results these algorithms might produce, whereas our UHS-Stream and the TFUHS-Stream algorithms are false-positive-oriented, and the false-positives are bounded by the (σ − ε) threshold. Also, for the TF model, they do not discuss how to decide on a value for the fading factor, while we explain how to compute it using the half-life principle. In the experiments section, we have shown that the proposed hyper-structure-based algorithms outperform the existing FP-growth-based algorithms in terms of accuracy, runtime, and memory usage.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we proposed two novel hyper-structure-based algorithms to mine frequent patterns from an uncertain data stream. To the best of our knowledge, the UHS-Stream algorithm proposed here is the first false-positive-oriented approach to find the complete set of frequent patterns from an uncertain stream of data. We also proposed the TFUHS-Stream algorithm to mine frequent patterns from an uncertain stream using a TF model. Both algorithms are false-positive-oriented and have a bound of (σ − ε), where σ is the minimum support threshold and ε is error margin such that ε ≪ σ. Experiments on both real-world and synthetic data show that the proposed algorithms clearly outperform the existing tree-based approaches in terms of accuracy, runtime, and memory consumption.

Biographies

Chandima Hewa Nadungodage received her B.Sc. in Computer Science and Engineering from University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka in 2005. Currently, she is a Ph.D. candidate at Department of Computer and Information Science, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). Her research interests include mining and management of evolving data streams, uncertain data streams and mining heterogeneous networks.

Chandima Hewa Nadungodage received her B.Sc. in Computer Science and Engineering from University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka in 2005. Currently, she is a Ph.D. candidate at Department of Computer and Information Science, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). Her research interests include mining and management of evolving data streams, uncertain data streams and mining heterogeneous networks.

Yuni Xia is an Associate Professor of the Department of Computer and Information Science, IUPUI. She received her B.S. in Computer Science from Huazhong University of Science and Technology in China in 1996, and her M.S. and Ph.D. in Computer Science from Purdue University in 2002 and 2005. Her research is on data mining and databases, focusing on mining and management of uncertain data and constantly evolving data such as sensor data and moving object data. She also works on data storage, retrieval, management and mining in data-intensive applications.

Yuni Xia is an Associate Professor of the Department of Computer and Information Science, IUPUI. She received her B.S. in Computer Science from Huazhong University of Science and Technology in China in 1996, and her M.S. and Ph.D. in Computer Science from Purdue University in 2002 and 2005. Her research is on data mining and databases, focusing on mining and management of uncertain data and constantly evolving data such as sensor data and moving object data. She also works on data storage, retrieval, management and mining in data-intensive applications.

Jaehwan John Lee is an Associate Professor of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at IUPUI. He received his B.S. degree from Kyungpook National University, Korea, and his M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical and Computer Engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 2003 and in 2004, respectively. His research interests include novel hardware-oriented or GPGPU-based parallel algorithms, computer architecture simulation, and FPGA-assisted real-time streaming data processing systems for multimedia sensor networks.

Jaehwan John Lee is an Associate Professor of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at IUPUI. He received his B.S. degree from Kyungpook National University, Korea, and his M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical and Computer Engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 2003 and in 2004, respectively. His research interests include novel hardware-oriented or GPGPU-based parallel algorithms, computer architecture simulation, and FPGA-assisted real-time streaming data processing systems for multimedia sensor networks.

Yi-cheng Tu is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at University of South Florida. He received his M.S. in Computer Science from Purdue University in 2003, and his Ph.D. in Computer Science from Purdue University in 2007. His research interests are in the areas of database systems, distributed systems, and high performance computing.

Yi-cheng Tu is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at University of South Florida. He received his M.S. in Computer Science from Purdue University in 2003, and his Ph.D. in Computer Science from Purdue University in 2007. His research interests are in the areas of database systems, distributed systems, and high performance computing.

Footnotes

Any ordering will work; alphabetical ordering is used for the convenience of explanation.

As proposed in [18], existential probability values rounded off to 2 decimal places in UFP-Stream and LUF-Stream implementations.

Contributor Information

Chandima HewaNadungodage, Email: chewanad@iupui.edu, Department of Computer and Information Science, Indiana University—Purdue University Indianapolis, 723 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202-5132, USA.

Yuni Xia, Email: yxia@iupui.edu, Department of Computer and Information Science, Indiana University—Purdue University Indianapolis, 723 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202-5132, USA.

Jaehwan John Lee, Email: johnlee@iupui.edu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Indiana University—Purdue University Indianapolis, 723 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202-5132, USA.

Yi-cheng Tu, Email: ytu@cse.usf.edu, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of South Florida, 4202 E. Fowler Ave., ENB 118, Tampa, FL 33620, USA.

References

- 1.Aggarwal CC, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Frequent pattern mining with uncertain data. Proceedings of the ACM-SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining; 2009. pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal R, Srikant R. Fast algorithms for mining association rules. Proceedings of the international conference on very large data,Bases; 1994. pp. 487–499. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal R, Srikant R. Mining sequential patterns. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on data, engineering; 1995. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernecker T, Kriegel H-P, Renz M, et al. Probabilistic frequent itemset mining in uncertain databases. Proceedings of the ACM-SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining; 2009. pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyer K, Ramakrishnan R. Bottom-up computation of sparse and iceberg cubes. Proceedings of the ACM-SIGMOD international conference on management of data; 1999. pp. 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brijs T, Swinnen G, Vanhoof K, et al. The use of association rules for product assortment decisions: a case study. Proceedings of the fifth international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining; 1999. pp. 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng J, Ke Y, Ng W. A survey on algorithms for mining frequent itemsets over data streams. Knowl Inf Syst. 2008;16(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chui C-K, Kao B, Hung E. Mining frequent itemsets from uncertain data. Proceedings of the Pacific-Asia conference advances in knowledge discovery and data mining; 2007. pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chui C-K, Kao B. A decremental approach for mining frequent itemsets from uncertain data. Proceedings of the Pacific-Asia conference advances in knowledge discovery and data mining; 2008. pp. 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giannella C, Han J, Pei J, et al. Mining frequent patterns in data streams at multiple time granularities. In: Kargupta H, Joshi A, Sivakumar K, Yesha Y, editors. Data mining: next generation challenges and future directions. AAAI/MIT Press; Menlo park/Cambridge: 2004. pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han J, Pei J, Yin Y. Mining frequent patterns without candidate generation. Proceedings of the ACM-SIGMOD international conference on management of data; 2000. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuramochi M, Karypis G. Frequent subgraph discovery. Proceedings of the international conference on data mining; 2001. pp. 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung CK-S, Mateo MAF, Brajczuk DA. A tree-based approach for frequent pattern mining from uncertain data. Proceedings of the Pacific-Asia conference on advances in knowledge discovery and data mining; 2008. pp. 653–661. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung CK-S, Hao B. Mining of frequent itemsets from streams of uncertain data. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on data engineering; 2009. pp. 1663–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung CK-S, Jiang F. Frequent itemset mining of uncertain data streams using the damped window model. Proceedings of the ACM symposium on applied computing; 2011a. pp. 950–955. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung CK-S, Jiang F. Frequent pattern mining from time-fading streams of uncertain data. Proceedings of DaWaK’11; 2011b. pp. 252–264. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung CK-S, Jiang F, Hayduk Y. A landmark-model based system for mining frequent patterns from uncertain data streams. Proceedings of IDEAS’11; 2011. pp. 249–250. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H-F, Shan M-K, Lee S-Y. DSM-FI: an efficient algorithm for mining frequent itemsets in data streams. Knowl Inf Syst. 2008;17(1):79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lian W, Cheung DW, Yiu SM. Maintenance of maximal frequent itemsets in large databases. Proceedings of the ACM symposium on applied computing; 2007. pp. 388–392. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H, Lin Y, Han J. Methods for mining frequent items in data streams: an overview. Knowl Inf Syst. 2011;26:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manku GS, Motwani R. Approximate frequency counts over data streams. Proceedings of the International conference on very large data bases; 2002. pp. 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mozafari B, Thakkar H, Zaniolo C. Verifying and mining frequent patterns from large windows over data streams. Proceedings of the IEEE 24th international conference on data engineering; 2008. pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng W, Dash M. Efficient approximate mining of frequent patterns over transactional data streams. Proceedings of the 10th international conference on data warehousing and knowledge discovery; 2008. pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pei J, Han J, Lu H, et al. H-mine: hyper-structure mining of frequent patterns in large databases. Proceedings of the international conference on data mining; 2001. pp. 441–448. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodríguez-González AY, Martínez-Trinidad JF, Carrasco-Ochoa JA, et al. RP-Miner: a relaxed prune algorithm for frequent similar pattern mining. Knowl Inf Syst. 2011;27(3):451–471. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salam A, Khayal MSH. Mining top-k frequent patterns without minimum support threshold. Knowl Inf Syst. 2012;30(1):57–86. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu JX, Chong Z, Lu H, et al. False positive or false negative: mining frequent itemsets from high speed transactional data streams. Proceedings of the international conference on very large data bases; 2004. pp. 204–215. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, Li F, Yi K. Finding frequent items in probabilistic data. Proceedings of the ACM-SIGMOD international conference on management of data; 2008. pp. 819–832. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Peng H. A sliding-window approach for finding top-k frequent itemsets from uncertain streams. Proceedings of the joint international conference on advances in data and web management; 2009. pp. 597–603. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng X, Pei J, Wang K, et al. PADS: a simple yet effective pattern-aware dynamic search method for fast maximal frequent pattern mining. Knowl Inf Syst. 2009;20(3):375–391. [Google Scholar]